Abstract

Introduction

Alaska Native and American Indian (AN/AI) populations have higher tobacco use prevalence than other ethnic/racial groups. Pharmacogenetic testing to tailor tobacco cessation treatment may improve cessation rates. This study characterized polymorphic variations among AN/AI people in genes associated with metabolism of nicotine and drugs used for tobacco cessation.

Methods

Recruitment of AN/AI individuals represented six subgroups, five geographic subgroups throughout Alaska and a subgroup comprised of AIs from the lower 48 states living in Alaska. We sequenced the CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 genes to identify known and novel gain, reduced, and loss-of-function alleles, including structural variation (eg, gene deletions, duplications, and hybridizations).

Results

Variant allele frequencies differed substantially between AN/AI subgroups. The gene deletion CYP2A6*4 and reduced function CYP2A6*9 alleles were found at high frequency in Northern/Western subgroups and in Lower 48/Interior subgroups, respectively. The reduced function CYP2B6*6 allele was observed in all subgroups and a novel, predicted reduced function CYP2B6 variant was found at relatively high frequency in the Southeastern subgroup.

Conclusions

Diverse CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 variation among the subgroups highlight the need for comprehensive pharmacogenetic testing to guide tobacco cessation therapy for AN/AI populations.

Implications

Nicotine metabolism is largely determined by CYP2A6 genotype, and variation in CYP2A6 activity has altered the treatment success in other populations. These findings suggest pharmacogenetic-guided smoking cessation drug treatment could provide benefit to this unique population seeking tobacco cessation therapy.

Introduction

Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable illness and death in the United States.1,2 Alaska Native and American Indian (AN/AI) people living in Alaska have one of the highest tobacco use rates in the United States, with 42% of AN adults versus 17% of non-AN adults living in Alaska reporting smoking in 2014.3 Without treatment, only 4%–7% of US smokers in a general population are able to quit smoking permanently and long-term quit rates with therapeutic assistance rarely exceed 30%.4

Pharmacogenetic testing has the potential to optimize tobacco cessation (TC) therapy, guiding drug dosing or treatment choice for individual patients to improve drug response and/or reduce adverse drug reactions.5 Genetic factors account for approximately 50% of the variance in smoking cessation success.6 Nicotine, the primary addictive substance in cigarettes,4 is metabolized predominantly by the enzyme cytochrome P450 2A6 (CYP2A6).7–10 Variation in the CYP2A6 gene contributes to inter-individual and inter-ethnic differences in nicotine metabolism, disposition, and response.10–14 Individuals with the CYP2A6 slow metabolizer phenotype generally smoke fewer cigarettes and respond better to the nicotine patch therapy than normal metabolizers. While both slow and normal CYP2A6 metabolizers respond better (eg, greater efficacy) to varenicline than to the patch, slow metabolizers exhibit a more debilitating side effect profile to varenicline than normal metabolizers.15–19 Hence, the nicotine patch is the preferred initial treatment for slow CYP2A6 metabolizers, if the nicotine metabolic phenotype or CYP2A6 genotype is known. The enzyme cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6), contributes significantly to the metabolism of bupropion, another drug used to facilitate TC, with slower metabolism from bupropion to hydroxybupropion, the active metabolite, in individuals with reduced function genetic variants.20 Individuals with lower plasma hydroxybupropion levels have lower quit rates when receiving bupropion suggesting that those with slow CYP2B6 genotypes may require higher doses or alternative treatments.13,21

Key to the success of genomic-guided TC therapy is knowledge of genetic variation in CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 genes and the associated drug metabolism activity in the population receiving treatment.5 However, such data are limited for AN/AI populations for various reasons, including a history of research misconduct with AN/AI communities.22,23 Available data suggest up to 25% of AN/AI populations will have CYP2A6 genetic variants that confer reduced metabolic function.24–26 However, results from these limited studies may not translate to all AN/AI peoples, given the historical geographic isolation and cultural heterogeneity of the AN/AI populations living in Alaska.24 In addition, comparing the AN/AI populations studied to the general US population, a higher rate of nicotine metabolism in AN/AI individuals, among those without reduced or loss-of-function alleles, suggests the presence of novel variation that confers increased CYP2A6 activity.24–27

In this study, we implemented targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) as a platform to identify novel and known CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 variation that might affect nicotine and bupropion metabolism in an AN/AI population living in the southcentral region of Alaska, representing all major Alaskan geographical subgroups, and to infer individual phenotypes for nicotine and bupropion metabolism. This knowledge could support the use of pharmacogenetic testing to guide personalized TC treatment for AN/AI people.

Methods

Study Participants

Between 2015 and 2016, 522 self-identified AN/AI individuals, ≥18 years of age, were recruited at Southcentral Foundation’s (SCF) primary care clinics. SCF is a tribally owned and operated health care corporation that provides pre-paid healthcare services to 65 000 AN/AI people in both urban and rural areas of Alaska.28,29 An intentional sampling strategy was used to ensure adequate participation from all geographic regions of Alaska, which provides representation for the major tribal groups. For the purpose of data analysis, study participants were grouped based on geographic and language similarities of self-identified affiliations: Southwestern (Aleut, Aluutiq, Sugpiaq), Northern (Inupiaq), Western (Yup’ik, Cup’ik, Siberian Yup’ik), Southeastern (Tlingit, Tsimshian, Haida, others), Interior (Athabascan), and an aggregate of tribal groups from the Lower 48 states of the United States who relocated to Alaska. Participants chose up to three subgroups, with the majority (62%) of participants affiliated with a single subgroup and another 31% affiliated with two subgroups.

Consented participants completed a short demographic questionnaire, and a blood sample was collected. The Alaska Area Institutional Review Board and SCF research review boards approved the study protocol and recruitment materials. A certificate of reliance was obtained from the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Sample Processing and Storage

Genomic DNA was isolated from buffy coat for each sample using QIAamp DNA blood kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). A total of 50 samples (out of 522) were excluded from further analysis because of low DNA yield, leaving 472 for further consideration. Selected samples (n = 282), representing the six specific geographic subgroups, were sent to Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center for CYP2A6 and CYP2B6-specific NGS. In addition, all samples (n = 472) were prepared for genotyping using nested real-time PCR and Taqman copy number assay methods.30,31

CYP2A6 and CYP2B6-Specific Sequencing

The CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 loci were sequenced using a novel NGS method developed by the Pharmacogenomics Research Network, and described in detail by Tanner et al.32 Briefly, tiled probes spanned a 292,502 bp segment between the 3′-flanking region of the CYP2A6 and CYP2A13 genes (Supplementary Figure 1). This region included CYP2A6, CYP2A7, CYP2G1P, CYP2B7 CYP2B6, CYP2A13 genes, and pseudogenes. All exons, introns, and regions 2 kilobases upstream and 1 kilobases downstream were analyzed for determination of CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 genomic variation. Probes were designed to ensure gene-specific sequencing, with attention paid to the high homology between the functional genes and associated pseudogenes. Library preparation, sequence capture, sequencing on Illumina MiSeq, and sequence analysis were performed according to the detailed protocol outlined in Tanner et al.32 Further bioinformatic analyses were used to predict CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 function of novel variants (eg, SNPNexus33).

Application of Stargazer for CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 Genotyping and Structural Variation

Analysis of CYP2A6 variation is complex because of the existence of single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertion-deletions (indels), and structural variants (SVs). SVs such as gene deletions, duplications, hybrids, and conversions, are particularly challenging to detect due to the high-sequence homology (94%) between CYP2A6 with its paralog, CYP2A7. A similar issue exists for CYP2B6 and its paralog, CYP2B7 (94% similarity). The program Stargazer was initially developed at the University of Washington to call star alleles of CYP2D6/CYP2D7 using NGS data34 and was recently extended to call alleles of CYP2A6/CYP2A7 and CYP2B6/CYP2B7, among many other pharmacogenes. Structural variation was detected by calculating paralog-specific copy number from read depth. The output data of Stargazer included each sample’s CYP2A6 diplotype and predicted phenotype, as designated by the Pharmacogene Variation Consortium (https://www.pharmvar.org/), and representative plots for visual inspection of paralog-specific copy number for CYP2A6/CYP2A7 (Figure 1) and for CYP2B6/CYP2B7 (Supplementary Figure 5). In a simultaneous analysis of variants in each (CYP2A6 and CYP2B6) loci, all SNVs and indels from the multi-sample VCF file were manually inspected, annotated, and allele frequencies were calculated separately. The data was then phased using the PHASE2.1.1 software, and resulting gene diplotypes were then compared with Stargazer calls at the end. Phased data was also used to detect the CYP2A6 5-SNP diplotypes discussed below.

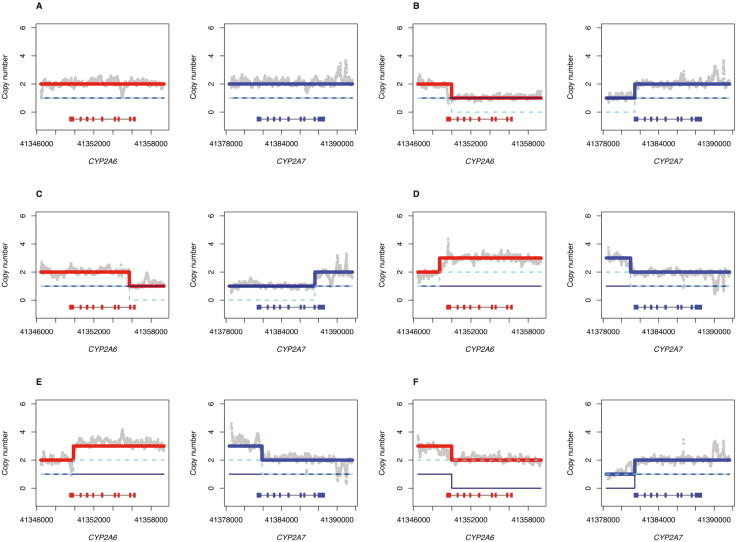

Figure 1.

Stargazer predictions of structural variation in the CYP2A6 and CYP2A7 genes Structural variants detected by Stargazer. Grey dots denote copy number calculated from read depth. The navy solid and cyan dashed lines represent two sequence structures that are being tested against the observed copy number of the sample. The red and blue lines represent theoretical copy number profiles for CYP2A6 and CYP2A7, respectively, formed by combining the two sequence structures in question. Each panel contains scaled CYP2A6 and CYP2A7 gene models, in which the exons and introns are depicted with boxes and lines, respectively. The gene models are arranged in the 3′–>5′ direction, as the sequence is aligned to the reverse strand. (A) Individual 1 has a CYP2A6*1/*35 diplotype without structural variation; this sample was included for comparison. (B) shows a gene deletion in Individual 2 that has a CYP2A6*1/*4 diplotype. (C) shows a CYP2A6/CYP2A7 hybrid in Individual 3 that has a CYP2A6*1/*12 diplotype. (D) shows a gene duplication in Individual 4 that has a CYP2A6*9/*1+*S1 diplotype. (E) shows another gene duplication in Individual 5 that has a CYP2A6*1/*1x2A diplotype. (F) shows both a gene deletion and a gene duplication in Individual 6 that has a CYP2A6*4/*1x2 diplotype.

Allele-Specific CYP2A6 Genotyping

The following high-frequency CYP2A6 star alleles (both SVs and SNVs) identified by NGS in the 282 sample group were selected for confirmatory genotyping analysis: *1X2A, *4, *9, *12 and *35. Low-frequency variants and star alleles with normal function were not selected for additional genotyping. We also genotyped the remaining 190 samples collected from the larger 472 SCF study cohort, to establish overall allele frequencies in the entire SCF study cohort for these variants. In addition, all 472 study samples were genotyped with real-time SYBR green PCR assays for CYP2A6*1B,34 as the 58-bp CYP2A7 gene conversion in the 3′UTR of CYP2A6 is a complicated region for NGS.

We followed the specific genotyping procedures outlined by Tyndale and colleagues using two methods: (1) a two-step, region-specific PCR reaction coupled with a variant-specific RT-PCR assay (CYP2A6*1B, *9, and *35) and (2) Taqman copy number assays (CYP2A6*1x2, *4, and *12 SVs).30,31 Phasing of CYP2A6 variants was determined from a combination of automated calls of the Stargazer NGS data and manual calls of the genotyping data.

Statistical Analysis

CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 allele frequencies were calculated with two-sided 95% confidence intervals. Analysis of DNA from 472 subjects provided a high level of confidence for variant frequency > 1% across total group. In a sub-analysis, common allele frequencies for the six subgroups (Southwestern, Interior, Northern, Western, Southeastern, and Lower 48) were compared using chi-square tests of proportions. Based on the known frequency of reduced function alleles in the Yup’ik population,24 for each allele, we expected to detect any 25% difference in frequency between the Yup’ik population and each of the subgroups, with power ranging from 82% to 91%, depending on the subgroup and the allele being compared.

SNV sites were assessed for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) using an exact test,35 and sites with a p-value below the threshold of .001 were taken to be out of HWE, and excluded from haplotype analysis. HWE was calculated for the entire SCF cohort as well as by individual subgroups that underwent NGS (n = 282). Linkage disequilibrium (LD) within CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 was assessed using Haploview,36 which computes pairwise LD statistics for variants.

Results

CYP2A6 Variation

NGS sequencing of CYP2A6 identified a total of 152 SNVs in the 282 samples examined (Supplementary Table 1), a frequency rate comparable to that of other populations analyzed to date (Supplementary Table 2).37 All SNVs had read-depths greater than 50, and only sites with genotype call rates of >75% in the cohort were considered in further analysis. Most SNVs were in HWE, except for the following seven: rs113777046, rs112026263, chr19: 41349636, chr19:41349906, rs201920184, rs1137115, and rs2644914. SNVs out of HWE were included in the frequency tables and reported overall results, but were not included in subsequent haplotype and phasing analysis.

Most SNVs occurred in the intronic and promoter regions (Supplementary Table 3). There were no novel coding variants, but 48 noncoding variants without designated reference SNP (rs) IDs were found at low frequencies in other regions of the gene; these variants are referred to as “rsNA” and are designated with chromosome: position in further Tables (Supplementary Tables 1 and 4). Further annotation for variants with SNPNexus33 predicted 13 possibly damaging CYP2A6 coding variants (eg, Sift and Polyphen Predictions), though these all corresponded to known functional star alleles (Supplementary File 1). All SNVs with MAF > 5% were previously identified in other populations.37

We identified the following SNVs in the CYP2A6 gene which have known enzyme function changing effects, *2, *5, *9, *10, *14, *18, *21, and *35 (Table 1).7,24,38–44 The pattern of allele frequencies revealed marked differences between the six geographic subgroups. All function disrupting SNVs were at relatively low frequency (less than 3%) in all subgroups with the exception of *9, which ranged from 2.6% to 15.6% in the subgroups. The Interior (13.6%) and the Lower 48 (15.6%) subgroups had the highest frequencies of *9, a promoter SNV that interrupts the TATA box (A>C) and results in decreased mRNA expression.45 The putative gain-of-function CYP2A6*1B allele, assigned by targeted RT-PCR, was found at an overall allele frequency of 53.7%. It was relatively high in all subgroups (45%–65%), but highest in the Southeastern, Western, and Northern subgroups. In the absence of confirmatory in vivo data in the SCF population, we elected to classify the *1B allele as conferring normal activity, although there does appear to be a modest increase in activity in other populations.

Table 1.

Comparison of SCF Cultural Subgroup CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 Allele Variant Frequencies (n = 282) With Frequencies From Previously Studied AN/AI Populations

| Allele frequencies (%) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Activity | Southwestern | Northern | Western | Southeastern | Interior | Lower 48 | Yup’ika | Northern Plainsb | Southwestb | Whitec | African Americanc | Japanesec |

| n = 42 | n = 55 | n = 59 | n = 37 | n = 57 | n = 32 | n = 361 | n = 318 | n = 172 | |||||

| CYP2A6 | |||||||||||||

| *1X2A | Increase | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| *1B | Increase | 44.3 | 60.9 | 55.2 | 61.8 | 50.9 | 46.9 | 65.3 | 69.7 | 61.6 | 26.7–35.0 | 11.2–18.2 | 25.6–54.6 |

| *2 | None | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.1–5.3 | 0–1.1 | 0.0 |

| *4 | None | 2.3 | 5.5 | 13.8 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 14.5 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.13–4.2 | 0.5–2.7 | 17.0–24.2 |

| *5 | None | 1.1 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | - | - | 0–0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| *7 | Decrease | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0–0.3 | 0.0 | 6.3–12.6 |

| *8 | Normal | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | - | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0–1.1 |

| *9 | Decrease | 6.8 | 6.4 | 7.8 | 2.6 | 14.5 | 15.6 | 8.9 | 11.9 | 20.9 | 5.2–8.0 | 5.7–9.6 | 19.0–20.7 |

| *10 | Decrease | 1.1 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 1.9 | - | - | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.2 |

| *12 | Decrease | 0.0 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0–3.0 | 0–0.4 | 0–0.8 |

| *14 | Unknown | 6.8 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 0.0 | - | - | - | 3.5–5.7 | 1.4–2.5 | 0.0 |

| *17 | Decrease | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.1–10.5 | 0.0 |

| *18 | Decrease | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | - | - | 1.1–2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| *21 | Normal | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 3.1 | - | - | - | 0–2.3 | 0–0.6 | 0.0 |

| *35 | Decrease | 1.1 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 2.5–2.9 | 0.8 |

| *1+*S1 | Unknown | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| CYP2B6 | |||||||||||||

| *2 | Unknown | 3.4 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.6 | - | - | - | 4.6 | 2.6 | 3.9 |

| *4 | Increase | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | - | 3.9 | 0.0 | 6.0 |

| *5 | Unknown | 5.7 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 4.5 | 4.7 | - | - | - | 9.6 | 3.3 | 1.0 |

| *6 | Decrease | 25.0 | 41.8 | 48.3 | 64.5 | 40.9 | 32.8 | 51.7 | - | - | 25.6 | 32.8 | 18.0 |

| *9 | Unknown | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | - | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| *10 | Unknown | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| *11 | Decrease | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 1.6 | - | - | - | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| *14 | Decrease | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | - | - | - | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| *15 | Decrease | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | - | - | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| chr19: 41512949 | Novel syn | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| chr19: 41518386 | Novel mis | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 10.5 | 0.9 | 0.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

AIAN populations include aBinnington et al. 2012 and bTanner et al. 2017. The Northern Plains and Southwest populations from Tanner et al. 2017 are American Indian populations recruited from South Dakota and from the Southwest in Arizona, respectively, and do not represent Alaska Native populations. Non-AIAN population frequencies were included from the c1000 Genomes as well as Binnington et al. 2012. The “-” designates those frequencies that were not determined in the previous studies.

We also identified structural variation in the CYP2A6 gene including the established gene deletion (*4), gene duplication (*1x2A) and CYP2A6-CYP2A7 hybridization (*12) events, initially using Stargazer and further confirmed with TaqMan copy number assays (Table 1). The SV calls in the subset of validated samples were identical to those called by Stargazer, so we are confident in the remaining Stargazer calls for CYP2A6*4, *12, and 1x2. The *4 deletion allele was present at high frequencies in certain cultural subgroups (ie, Southwestern [2.3%], Northern [5.5%], Western [13.8%]) and absent or at low frequencies in others (ie, Southeastern [0.0%], Interior [0.9%], and Lower 48 [0.0%]). We detected a *4 homozygous deletion in two individuals from the Western subgroup (confirmed by Taqman assays) and, with NGS data, were able to map the exact breakpoints of the deletion in these individuals (Supplementary Figure 3). The *12 allele is a hybrid of sequence from both CYP2A6 and CYP2A7 genes; exons 1–2 from CYP2A7 and exons 3–9 from CYP2A6. It was found at a frequency of 1.3% in the Southeastern, 0.9% in the Northern, 2.6% in the Western subgroups, and absent from the Southwestern, Interior and Lower 48 subgroups (Table 1). In addition, we identified CYP2A6 duplications (*1X2A) in three individuals, with each individual having three copies of the CYP2A6 gene; two from the Interior and one from Northern subgroups. There were also multiple examples of non-homologous recombinations in the 3′-flanking-intron 8 region of CYP2A6; some of these could be assigned an allele and predicted phenotype (generally, reduced function) based on the presence of diagnostic SNVs, but others could not. In particular, we identified a novel SV assigned the name *1+*S1, with two normal copies and a hybrid copy with a breakpoint in the 3′UTR (Figure 1D), which did not match any alleles listed in PharmVar.

CYP2A6 LD Patterns

Patterns of CYP2A6 LD were assessed from the NGS data (n = 282) using Haploview. LD was calculated between every SNV in the gene, and shown are those SNVs with a MAF > 5% (Supplementary Figure 4). Two blocks in high LD were found. The first was between two SNVs located within intron 4. The second included 10 SNVs that were located within intron 2 and the promoter region of the CYP2A6 gene.

Tanner et al.32 recently reported identifying haplotypes consisting of five noncoding SNVs (rs28399453, rs56113850, rs150298687, rs7260629, and rs57837628) that were associated with a modest gain of CYP2A6 metabolic function in vitro and in vivo. The same five-SNVs were detected in the SCF study cohort at relatively high frequency (Supplementary Table 4). SNV rs28399453 was not in LD with any other the other SNVs (r′ = 0, D′ = 0) and the remaining four SNVs had some levels of LD between each other (r′ = .40–.86).

Phased CYP2A6 Genotype Frequencies and Predicted Diplotypes

We were able to call the phase of individuals with a combination of SVs, SNVs and the genotyped *1B allele for 269/282 in the NGS cohort (Supplementary Table 5) and to predict diplotypes of variants with known star alleles (Table 2). Based on those results, 10.4% were classified as a slow or poor metabolizer phenotype (at least one null or decreased function genotypes), 21.3% were classified as intermediate metabolizer phenotype (one or two decreased function genotypes), and 66.6% classified as normal metabolizer phenotype. In addition, we found combinations of decreased function SNVs on the same haplotype (ie, *9 and *18 on the same gene copy) that may be unique to these subgroups (Supplementary Table 5 and Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequencies of Predicted Phenotypes of all Phased CYP2A6 Diplotypes Found in SCF Subgroups (n = 269)

| Southwestern | Northern | Western | Southeastern | Interior | Lower 48 | SCF | Phenotype class | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 40 | n = 52 | n = 58 | n = 33 | n = 56 | n = 30 | n = 269 | ||

| *1/*1 | 10.0 | 3.8 | 13.8 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 3.3 | 8.2 | Normal |

| *1/*14 | 12.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.2 | Normal |

| *1/*1B | 32.5 | 32.7 | 24.1 | 39.4 | 28.6 | 40.0 | 31.6 | Normal |

| *1B/*1B | 20.0 | 25.0 | 24.1 | 45.5 | 19.6 | 13.3 | 24.2 | Normal |

| *1B/*1B+*14 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | Normal |

| *1/*21 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 6.7 | 1.5 | Normal |

| *1/*9 | 10.0 | 9.6 | 6.9 | 6.1 | 26.8 | 30.0 | 14.5 | Intermediate |

| *1/*12 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 5.2 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.9 | Intermediate |

| *1/*28 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | Intermediate |

| *1/*35 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | Intermediate |

| *1B/*1B+*10 | 0.0 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 1.5 | Intermediate |

| *1B/*1B+*35 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | Intermediate |

| *14/*18 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | Intermediate |

| *1/*2 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 1.1 | Slow |

| *1/*4 | 2.5 | 3.8 | 6.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.6 | Slow |

| *1B/*4 | 0.0 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.9 | Slow |

| *1B+*2/*1B+*9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | Slow |

| *2/*9 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | Slow |

| *4/*9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | Slow |

| *4/*14 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.4 | Slow |

| *10/*9+*18 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | Slow |

| *4/*1B+*5 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | Poor |

| *4/*4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | Poor |

| *4/*5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | Poor |

| *4/*5+*9 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | Poor |

| *1x2A | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | Rapid |

| *9/*1x2A | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.4 | Normal |

| *1/*1+*S1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.3 | 0.4 | Unknown |

| *9/*1+*S1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.3 | 0.4 | Unknown |

We obtained activity data for CYP2A6 from the old CYP nomenclature website (now PharmVar; https://www.pharmvar.org), where none = 0, decreased = 0.5, and normal = 1. To convert from activity score to phenotype class (or metabolizer phenotype), we used this criteria: Poor (activity score = 0), Slow (activity score 0 to <1), Intermediate (activity score 1 to <2), Normal (activity score 2 to <3), and Rapid (activity score > 3).

We also computed from sequencing data diplotypes based solely on the 5-SNV haplotype reported recently by Tanner et al.32 Following statistical phasing, we identified 18 diagnostic diplotypes, with some small differences between cultural subgroups (Table 3). Diplotypes #1, #2, and #6 were highest in observed frequency in the SCF cohort.

Table 3.

Five-SNP Phased CYP2A6 Diplotypes Found in SCF Subgroups (n = 282)

| Diplotype frequencies (%) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diplotype group# | Full diplotype | South- western | Northern | Western | South eastern | Interior | Lower 48 | SCF | Liver banka | PNATa | CYP2A6 activity (liverbank) | CYP2A6 activity (PNAT) | Corresponding liver bank and PNAT diplotype group |

| Reference | G T T T A / G T T T A | 9.1 | 5.5 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 0.07 | 0.3 | Reference |

| 1 | G C C G G / G C C G G | 36.4 | 45.5 | 60.3 | 55.3 | 36.4 | 18.8 | 43.6 | 25.0 | 17.2 | 0.13 | 0.55 | 1, 1 PNAT |

| 2 | G T T T A / G C C G G | 27.3 | 20.0 | 8.6 | 21.1 | 20.0 | 34.4 | 20.6 | 23.4 | 19.2 | 0.09 | 0.4 | 2, 2 PNAT |

| 3 | G T T G A / G C C G G | 4.5 | 7.3 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 8.6 | 6.7 | 0.12 | 0.46 | 3, 3 PNAT |

| 4 | G C C G A / G C C G G | 0.0 | 7.3 | 5.2 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 3.9 | 6.6 | 8.6 | 0.1 | 0.55 | 4, 4 PNAT |

| 5 | G T T T A / G T T G A | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 5.9 | 3.1 | 0.08 | 0.38 | 5, 5 PNAT |

| 6 | G T C G A / G C C G G | 9.1 | 9.1 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 20.0 | 28.1 | 12.1 | 0.4 | - | 0.03 | - | 20 |

| 7 | G C C G G / A C C G G | 6.8 | 1.8 | 3.4 | 10.5 | 1.8 | 3.1 | 4.3 | 5.5 | 5.9 | 0.11 | 0.49 | 6, 6 PNAT |

| 8 | G T T T A / A C C G G | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 1.1 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 0.14 | 0.42 | 7, 7 PNAT |

| 9 | G T C G A / G T T T A | 4.5 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 2.1 | - | 0.2 | - | 0.22 | 39 PNAT |

| 10 | G T C G A / G T C G A | 0.0 | 1.8 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 11 | G C C T G / G C C G G | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | - | 1.6 | - | 0.6 | 20 PNAT |

| 12 | G T T T G / G C C G G | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 13 | G C C G A / G T T T A | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 3.1 | - | 0.08 | - | 8 |

| 14 | G T T G A / G T T G A | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.8 | - | 0.04 | - | 12 |

| 15 | G T C G A / G C C G A | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.4 | - | 0.23 | - | 19 |

| 16 | G T C G A / A C C G G | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.4 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 17 | G T T G A / G T C G A | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | - | - | - | - | - |

The in vitro human liver bank CYP2A6 enzyme activity (rate of cotinine formation from nicotine) was measured in nmol/min/mg, and the in vivo CYP2A6 activity (NMR) of the Pharmacogenetics of Nicotine and Addiction Treatment clinical trial (PNAT) was measured previously. Diplotype group frequencies and activities were extracted from aTanner et al. 2017. The diplotype group numbering from Tanner et al. 2017 was also extracted for comparison and is listed in the right column.

Additional allele-specific genotyping was conducted in 190 additional individuals to obtain overall SCF cohort (n = 472) frequencies shown in Supplementary Table 6. The overall frequencies of the selected alleles were similar to those of the NGS cohort.

CYP2B6 Variation

Resequencing of the CYP2B6 gene identified numerous SNVs of known and unknown significance (Supplemental Table 7), including *2, *4, *5, *6, *9, *10, *11, *14, *15 and a putative novel nonsynonymous variant in exon 7 with an amino acid 383 change from PRO>ARG (chr 19, position 41518386; Table 1). No CYP2B6-specific SVs were found in the SCF study cohort (Supplemental Figure 2). Two novel coding variants (a synonymous and nonsynonymous variant) and 63 noncoding variants without designated reference SNP (rs) IDs were found at low frequencies in throughout the gene. We highlight four high-frequency variants (rs2279343, rs3745274, rs3211371, 41518386) that define the *4, *5, *6, and *9 alleles, in addition to the novel nonsynonymous variant (Supplementary Table 4). The rs2279343 variant defines the CYP2B6*4, rs3211371 defines the *5, rs3745274 defines the *9, and the combination of rs2279343 and rs3745274 defines *6. The *6 variants (rs2279343 and rs3745274) were found in near complete LD in all individuals (Supplementary Figure 5; r2 = 99% and D′ = 1) and phasing indicated most individuals had the *6 haplotype at frequency of 42.4% in the SCF study cohort, similar to data reported for a Yup’ik population living in southwest Alaska.24 However, when the frequency of *6 was broken down by cultural subgroup, it was 64.5% and 48.3% in the Southeastern and Western (48.3%) subgroups, respectively, which was higher than that of the Southwestern (25%) and the Lower 48 (32.8%) subgroups. The novel variant 41518386 corresponds to a C>G change (PRO383ARG) in exon 7 and was found at high frequency in the Southeastern (10.5%) subgroup and at a lower frequency in the Western (0.9%) subgroup (Table 1). This variant was not found in any other subgroups or in any other population database (eg, 1000 Genomes, HapMap, or gnomAD) to date. Further annotation with Sift and Polyphen Predictions indicated that the novel variant was highly damaging (Supplementary File 1).

Discussion

In this study, we sequenced and genotyped the CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 gene loci to identify and characterize variation in AN/AI individuals recruited from an urban tribal health care setting in southcentral Alaska. The main findings of the study were: (1) many of the known common CYP2A6 variants were detected in the cohort, but allele frequencies often differed substantially between AN/AI subgroups, and 48 putative novel variants in the noncoding region were identified; (2) the loss-of-function CYP2A6*4 variant was relatively common in the Northern and Western subgroups, but nearly absent from all other AN/AI subgroups; (3) the reduced function CYP2A6*9 allele was more common in the Interior and Lower 48 subgroups, compared to the other subgroups; (4) the CYP2A6*1B allele and a CYP2A6 5-SNV haplotype that are associated with modest gain of catalytic function in other populations32,34 were found at high frequencies in all subgroups, which may perhaps contribute to relatively high rates of nicotine metabolism for these populations reported in other published studies.4,31 In addition, (5) many of the known common CYP2B6 variants were detected in the cohort and 65 putative novel variants, including two coding variants, were identified; (6) the CYP2B6*6 allele associated with a decrease in metabolism of bupropion was found at relatively high frequencies in all subgroups (25%–64.5%), perhaps contributing to a failure to quit smoking when receiving this therapy; (7) a novel CYP2B6 variant (PRO383ARG) was found at high frequency in the Southeastern subgroup (10.5%) which may decrease enzymatic activity and perhaps also contribute to ineffective bupropion therapy for smoking cessation.

The high homology between CYP2A6 and its paralog, CYP2A7 has made it challenging in the past to assign genetic variation to one gene or another. With NGS, probes were designed to ensure gene-specific sequencing and proper mapping, and great attention was paid to the high homology of CYP2A6, CYP2A7, and CYP2A13 and of CYP2B6 and CYP2B7. The identification of CYP2A6/CYP2A7 and CYP2B6/CYP2B7 SV and SNVs was greatly aided by implementation of Stargazer.46 Although overall performance of sequencing and data analysis was excellent, there is still clearly room for improvement, such as ensuring accurate capture of the CYP2A6*1B allele with NGS.

An intriguing finding of this study was the detection at relatively high frequency of a novel 5-SNP CYP2A6 diplotype that has recently been associated with a gain of function in nicotine metabolism in Americans of European descent, accounting for 3.9% additional variation in CYP2A6 activity than with established variants alone.32 First identified in a comprehensive analysis of genotype-phenotype relationships in a large human liver bank, the 5-SNP diplotype was associated with higher liver CYP2A6 protein content and higher cotinine formation from nicotine as well as a faster in vivo activity (NMR or the measure of 3-hydroxycotinine/cotinine concentration ratio).16,32 A high frequency of this diplotype and the CYP2A6*1B gain-of-function haplotype in the AN population, particularly in the Interior and Western subgroups, may contribute to higher NMRs (vs. other ethnicities) among a past study of Yup’ik people.24 Other factors (eg, diet and environment) might also contribute and additional functional associations need to be done in these populations. Because a high NMR is associated with reduced efficacy of nicotine replacement, the finding provides additional support for comprehensive phenotype prediction.

While the intentional sampling strategy of diverse tribal groups is a strength of this study, there were also relatively low numbers of individuals per subgroup and a heterogeneous tribal background for some subgroup representatives. We acknowledge that a limitation of this study is that we did not specifically ask for tribal enrollment status and relied on self-reported affiliations. These data suggest that sequencing or genotyping more individuals per subgroup are warranted in the future, especially with frequency variations between subgroups. Since nicotine metabolism is largely determined by CYP2A6 genotype, and variation in CYP2A6 activity (NMR) has altered treatment success in other populations,47 these findings suggest pharmacogenetic-guided smoking cessation drug treatment could provide benefit to this population seeking TC. However, complex factors that aid in successful TC therapy warrant an investigation into the relative contributions of patient, clinical, and genetic factors to successful TC to advance genomics-guided precision medicine for this historically underserved population. In addition, a future pragmatic clinical trial, which would test for efficacy and feasibility of genetic tailoring of different approaches, could be of value to inform health policy.

In summary, we have sequenced the CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 genes in AN/AI populations. The results from this study improve our understanding of the type and frequency of CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 variation in AN/AI populations, which vary substantially from other populations studied to date.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at Nicotine and Tobacco Research online.

Supplementary Figure 1. Next-generation sequencing of targeted region. The targeted sequencing region spanned from a 292,502 bp segment from the 3′-flanking region of the CYP2A6 gene to the 3′-flanking region of the CYP2A13 gene. The region included CYP2A6, CYP2A7, CYP2G1P, CYP2B7, CYP2B6, CYP2A13 genes, and pseudogenes. CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 were targeted for SNV detection. The CYP2A6, CYP2A7, CYP2B7, and CYP2B6 regions were targeted by Stargazer for structural variant detection. The CYP2G1P and CYP2A13 loci were used as read-depth control regions for both CYP2A6/CYP2A7 and CYP2B6/CYP2B7 by Stargazer.

Supplementary Figure 2. Stargazer predictions of structural variation in the CYP2B6 and CYP2B7 genes. The figure depicts the CYP2B6/CYP2B7 copy number plots from Stargazer for the same individuals in Figure 1. Grey dots represent copy number read depth, navy, and cyan dashed lines represent sequence structures tested against observed copy number, yellow-green, and magenta lines represent theoretical copy number for CYP2B6 and CYP2B7. Scaled gene models are arranged in the 5′–>3′ direction.

Supplementary Figure 3. Next-generation sequencing reads from individuals homozygous for the CYP2A6*4 deletion, both from the Western subgroup. The raw read map from IGV is displayed. Individual 1 and Individual 2 have a large deletion that spans from the 3′UTR of CYP2A6 to the 3-UTR of CYP2A7. Individual 3 does not have this deletion.

Supplementary Figure 4. Linkage disequilibrium and haplotype structure of SNVs in CYP2A6. Patterns of CYP2A6 LD were assessed from the NGS data (n = 282) using Haploview. LD was calculated between every SNV in the gene, and shown are those SNVs with a MAF > 5%.

Supplementary Figure 5. Linkage disequilibrium of two SNVs in CYP2B6. This figure shows the two CYP2B6 allelic variants (rs2279343 and rs3745274) that define the *4, *6 and *9 alleles that were found at an allele frequency of 60% and 60%, respectively, and were in near complete LD (r2 = .99 and D′ = 1)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Chung Nim Ha, David Chanar, Briana Triplett, Lisa Dirks, Divine Tate, Christopher Chong and Deanna Smith at Southcentral Foundation who assisted in recruitment and sample processing, Justina Calamia at the University of Washington, Richard Gibbs, Donna Muzny, HarshaVardhan Doddapaneni, Jianhong Hu and Will Salerno from the BCM-HGSC for data generation, and the study participants.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant numbers S06 GM123545 to JAB, S06 GM106351 to RFR, U01 GM092676 to KET, P01 GM116691 to KET, F32 GM119237 to KGC); Native American Research Centers for Health (grant number U26 1 IHS0079-01-00 to RFR, JAB, JPA, DAD), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (grant number P30 ES007033 to PAS); Canada Research Chair in Pharmacogenomics (to RFT); Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant number FDN-154294 to RFT); and the Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (to RFT). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Declaration of Interests

RFT has consulted for Apotex and Quinn Emmanuel on unrelated topics. There are no conflicts of interest by other authors.

References

- 1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General: Executive Summary. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. CDC. Smoking & Tobacco Use 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fast_facts/index.htm. Accessed December 7, 2017.

- 3. Services ADoHaS. Alaska Tobacco Facts 2016. http://dhss.alaska.gov/dph/Chronic/Documents/Tobacco/PDF/2016_AKTobaccoFacts.pdf. Accessed February 13, 2018.

- 4. Prochaska JJ, Benowitz NL. The past, present, and future of nicotine addiction therapy. Annu Rev Med. 2016;67:467–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Woodahl EL, Lesko LJ, Hopkins S, Robinson RF, Thummel KE, Burke W. Pharmacogenetic research in partnership with American Indian and Alaska Native communities. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15(9):1235–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xian H, Scherrer JF, Madden PA, et al. The heritability of failed smoking cessation and nicotine withdrawal in twins who smoked and attempted to quit. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(2):245–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nakajima M, Fukami T, Yamanaka H, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of variability in nicotine metabolism and CYP2A6 polymorphic alleles in four ethnic populations. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80(3):282–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nakajima M, Yamamoto T, Nunoya K, et al. Characterization of CYP2A6 involved in 3’-hydroxylation of cotinine in human liver microsomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277(2):1010–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Messina ES, Tyndale RF, Sellers EM. A major role for CYP2A6 in nicotine C-oxidation by human liver microsomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282(3):1608–1614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Benowitz NL, Swan GE, Jacob P III, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Tyndale RF. CYP2A6 genotype and the metabolism and disposition kinetics of nicotine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80(5):457–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wassenaar CA, Dong Q, Wei Q, Amos CI, Spitz MR, Tyndale RF. Relationship between CYP2A6 and CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4 variation and smoking behaviors and lung cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(17):1342–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wall TL, Schoedel K, Ring HZ, Luczak SE, Katsuyoshi DM, Tyndale RF. Differences in pharmacogenetics of nicotine and alcohol metabolism: Review and recommendations for future research. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(Suppl 3):S459–S474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee AM, Jepson C, Shields PG, Benowitz N, Lerman C, Tyndale RF. CYP2B6 genotype does not alter nicotine metabolism, plasma levels, or abstinence with nicotine replacement therapy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(6):1312–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schoedel KA, Hoffmann EB, Rao Y, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF. Ethnic variation in CYP2A6 and association of genetically slow nicotine metabolism and smoking in adult Caucasians. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14(9):615–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee AM, Tyndale RF. Drugs and genotypes: How pharmacogenetic information could improve smoking cessation treatment. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(4 Suppl):7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lerman C, Schnoll RA, Hawk LW Jr, et al. ; PGRN-PNAT Research Group Use of the nicotine metabolite ratio as a genetically informed biomarker of response to nicotine patch or varenicline for smoking cessation: a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(2):131–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mroziewicz M, Tyndale RF. Pharmacogenetics: A tool for identifying genetic factors in drug dependence and response to treatment. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2010;5(2):17–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tanner JA, Chenoweth MJ, Tyndale RF. Pharmacogenetics of nicotine and associated smoking behaviors. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2015;23:37–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thomas PD, Mi H, Swan GE, et al. ; Pharmacogenetics of Nicotine Addiction and Treatment Consortium A systems biology network model for genetic association studies of nicotine addiction and treatment. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2009;19(7):538–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Benowitz NL, Zhu AZ, Tyndale RF, Dempsey D, Jacob P III. Influence of CYP2B6 genetic variants on plasma and urine concentrations of bupropion and metabolites at steady state. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2013;23(3):135–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhu AZ, Cox LS, Nollen N, et al. CYP2B6 and bupropion’s smoking-cessation pharmacology: the role of hydroxybupropion. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92(6):771–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garrison NA. Genomic justice for Native Americans: impact of the Havasupai case on genetic research. Sci Technol Human Values. 2013;38(2):201–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mello MM, Wolf LE. The Havasupai Indian tribe case–lessons for research involving stored biologic samples. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(3):204–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Binnington MJ, Zhu AZ, Renner CC, et al. CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 genetic variation and its association with nicotine metabolism in South Western Alaska Native people. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2012;22(6):429–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhu AZ, Binnington MJ, Renner CC, et al. Alaska Native smokers and smokeless tobacco users with slower CYP2A6 activity have lower tobacco consumption, lower tobacco-specific nitrosamine exposure and lower tobacco-specific nitrosamine bioactivation. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(1):93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhu AZ, Renner CC, Hatsukami DK, Benowitz NL, Tyndale RF. CHRNA5-A3-B4 genetic variants alter nicotine intake and interact with tobacco use to influence body weight in Alaska Native tobacco users. Addiction. 2013;108(10):1818–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tanner JA, Henderson JA, Buchwald D, Howard BV, Nez Henderson P, Tyndale RF. Variation in CYP2A6 and nicotine metabolism among two American Indian tribal groups differing in smoking patterns and risk for tobacco-related cancer. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2017;27(5):169–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eby DK. Primary care at the Alaska Native Medical Center: a fully deployed “new model” of primary care. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2007;66(Suppl 1):4–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gottlieb K. The Nuka System of Care: Improving health through ownership and relationships. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72(1):21118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shimizu M, Koyama T, Kishimoto I, Yamazaki H. Dataset for genotyping validation of cytochrome P450 2A6 whole-gene deletion (CYP2A6*4) by real-time polymerase chain reaction platforms. Data Brief. 2015;5:642–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wassenaar CA, Zhou Q, Tyndale RF. CYP2A6 genotyping methods and strategies using real-time and end point PCR platforms. Pharmacogenomics. 2016;17(2):147–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tanner JA, Zhu AZ, Claw KG, et al. Novel CYP2A6 diplotypes identified through next-generation sequencing are associated with in-vitro and in-vivo nicotine metabolism. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2018;28(1):7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dayem Ullah AZ, Lemoine NR, Chelala C. SNPnexus: A web server for functional annotation of novel and publicly known genetic variants (2012 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Web Server issue):W65–W70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mwenifumbo JC, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Zhou Q, et al. Identification of novel CYP2A6*1B variants: The CYP2A6*1B allele is associated with faster in vivo nicotine metabolism. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83(1):115–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wigginton JE, Cutler DJ, Abecasis GR. A note on exact tests of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76(5):887–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: Analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. The Genomes Project C. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mwenifumbo JC, Tyndale RF. Genetic variability in CYP2A6 and the pharmacokinetics of nicotine. Pharmacogenomics. 2007;8(10):1385–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ho MK, Mwenifumbo JC, Al Koudsi N, et al. Association of nicotine metabolite ratio and CYP2A6 genotype with smoking cessation treatment in African-American light smokers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;85(6):635–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Malaiyandi V, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF. Implications of CYP2A6 genetic variation for smoking behaviors and nicotine dependence. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;77(3):145–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Haberl M, Anwald B, Klein K, et al. Three haplotypes associated with CYP2A6 phenotypes in Caucasians. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15(9):609–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fukami T, Nakajima M, Higashi E, et al. Characterization of novel CYP2A6 polymorphic alleles (CYP2A6*18 and CYP2A6*19) that affect enzymatic activity. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33(8):1202–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Al Koudsi N, Ahluwalia JS, Lin SK, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF. A novel CYP2A6 allele (CYP2A6*35) resulting in an amino-acid substitution (Asn438Tyr) is associated with lower CYP2A6 activity in vivo. Pharmacogenomics J. 2009;9(4):274–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Al Koudsi N, Mwenifumbo JC, Sellers EM, Benowitz NL, Swan GE, Tyndale RF. Characterization of the novel CYP2A6*21 allele using in vivo nicotine kinetics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62(6):481–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yoshida R, Nakajima M, Nishimura K, Tokudome S, Kwon JT, Yokoi T. Effects of polymorphism in promoter region of human CYP2A6 gene (CYP2A6*9) on expression level of messenger ribonucleic acid and enzymatic activity in vivo and in vitro. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74(1):69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lee SB, Wheeler MM, Patterson K, et al. Stargazer: A software tool for calling star alleles from next-generation sequencing data using CYP2D6 as a model. Genet Med. 2019;21(2):361–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tanner JA, Tyndale RF. Variation in CYP2A6 Activity and Personalized Medicine. J Pers Med. 2017;7(4):18. doi:10.3390/jpm7040018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.