Abstract

Background

Increasing tobacco taxes, and through them, prices, is an effective public health strategy to decrease tobacco use. The tobacco industry has developed multiple promotional strategies to undercut these effects; this study assessed promotions directed to wholesalers and retailers and manufacturer price changes that blunt the effects of tax and price increases.

Methods

We reviewed tobacco industry documents and contemporaneous research literature dated 1987 to 2016 to identify the nature, extent, and effectiveness of tobacco industry promotions and price changes used after state-level tobacco tax increases.

Results

Tobacco companies have created promotions to reduce the effectiveness of tobacco tax increases by encouraging established users to purchase tobacco in lower-tax jurisdictions and sometimes lowering manufacturer pricing to “undershift” smaller tax increases, so that tobacco prices increased by less than the amount of the tax.

Conclusions

Policymakers should address industry efforts to undercut an effective public health intervention through regulating minimum prices, limiting tobacco industry promotions, and by enacting tax increases that are large, immediate, and result in price increases.

Implications

Tobacco companies view excise tax increases on tobacco products as a critical business threat. To keep users from quitting or reducing tobacco use in response to tax increases, they have shifted manufacturer pricing and developed specific promotions that encourage customers to shop for lower-taxed products. Health authorities should address tobacco industry efforts to undercut the effects of taxes by regulating prices and promotions and passing large and immediate tax increases.

Background

Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of death in the United States, accounting for one of five deaths annually.1 An effective public health strategy for decreasing tobacco use is the imposition of “significant tobacco tax and price increases.”2,3 While increasing both taxes and prices are valuable public health goals, increasing tobacco taxes may not necessarily increase the prices paid by users and reduce consumption.4,5 The tobacco industry has expressed substantial concern about increased prices, whether caused by taxes or inflation, reducing demand and corporate profits.6 In the 1970s the tobacco industry limited price increases even though the inflation rate was high to maximize youth initiation, because young people are price-sensitive and less likely to take up smoking when cigarettes become more expensive.6 Reflecting similar concerns, tobacco companies work to undercut the effects of tobacco tax increases on price and demand7,8 by implementing price discounts and promotional allowances to retailers, as well as “undershifting” taxes by reducing wholesale prices at the same time that taxes increase.9

The Federal Trade Commission reported that, in 2004 and 2005, that the largest share of advertising and promotional spending, over 77%, was “price discounts … to reduce the price of cigarettes to consumers”10; that share increased to 83% and $7.25 billion in 2016 for cigarettes (62% and $468 million for smokeless tobacco).11–13 Promotions include: (1) discount coupons to consumers, either offered directly or through retailers; (2) price reductions for wholesalers for larger orders, which may be passed down to the retail level (off-invoice discounts); (3) buy-down programs in which retailers receive rebates for sales, (4) wholesale pricing agreements in which a wholesaler pays a rebate to retailer for sales (paperless coupons); and (5) retail value-added (typically buy-one-get-one-free). Most independent research on tobacco price promotions has focused on a few strategies: consumers buying cartons instead of packs for the volume discount, switching from “premium” to budget brands, direct-to-consumer coupons, and purchases made in lower-tax areas.14–21 Tobacco companies appear to increase the distribution of consumer-directed price promotions after the implementation of tax increases6,22,23; younger, heavy, and “premium” brand smokers are more likely to respond.20,24–26

Existing studies have noted the need for research on how the tobacco companies use promotions and their effects on tobacco use16,20 because the intended effects of tax increases may be undercut by recently expanded tobacco industry promotional strategies, including the development of new alternative tobacco products.8,18,27 Studies of other products for which there is relatively inelastic demand, such as gasoline, find that price promotions have been used to mask tax increases that would otherwise change purchasing behavior.28 Some tax increases, however, appear to be reflected in higher prices: tobacco companies responded to the 1983 federal tax increase from 8¢ to 16¢ by overshifting, increasing prices by more than the tax to maintain revenues in the face of declining sales volume.6,29 The tobacco industry’s response to much larger state-level tobacco tax increases in late 20th and early 21st century30 has not yet been assessed, in part due to limited information about when, where, and to what extent tobacco companies have used different promotional strategies and the difficulty of identifying industry strategies.

We used internal tobacco industry documents released under legal discovery to assess relationships between tobacco industry promotion strategies and increased state tobacco taxes to assess industry strategies that are often invisible to outside researchers. Public promotions such as consumer coupons and the creation and promotion of discount brands can be tracked using surveillance data,6,10,14–21,31 so we concentrated instead on promotions directed to wholesalers and retailers and on manufacturer price changes. We anticipated that while the tobacco industry approaches price increases in different ways, it has integrated its visible (coupons) and invisible (buybacks) promotions in order to reduce the impact of tax increases on consumers.

Methods

We searched the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents Library,32 which contains over 14 million related to the industry, between January and May 2018 using established snowball methods.33–38 Original searches focused on keywords (e.g. tax differential, border store) combined with delimiters like the names of individual states. Searches for a specific term or phrase typically result in hundreds or thousands of results, so documents are screened for relevance and duplication. We refined the original search terms and dates by adding the names of individuals and companies to restrict searches, and searching specifically for lobbying reports and marketing campaigns. We also searched nearby documents (using Bates numbers). Documents were aggregated into a historical timeline; when multiple documents made similar claims, documents were summarized. Important claims made in the documents have been quoted exactly. Following standard practices for tobacco documents research, we used triangulation among the available documents and with other sources, primarily research literature drawn from PubMed, to validate and contextualize the information we found in the documents.39,40 Our final analysis included ~90 tobacco industry documents and articles dated between 1987 and 2016.

Results

In 1985, a draft of a Philip Morris “discussion document used at the meeting of top management”41 explained that “Of all the concerns, there is one—taxation—that alarms us the most … [T]axation depresses [sales] severely.”42 Tobacco companies have historically responded to tobacco tax increases by offering consumer promotions in the form of coupons, promoting sales in lower-tax outlets and lowering wholesale prices.6 The companies track these outcomes to assess their marketing effectiveness.

Strategies to Undercut Regional Tax Increases: Tax Differential or Border Stores

One way that tobacco users can avoid paying more after a tax increase is by purchasing in lower-tax jurisdictions. “Tax differential stores” (Lorillard)43 or “border stores” (Philip Morris,44 RJ Reynolds45) are high-volume retail tobacco outlets “that attract carton consumers from bordering high tax areas.”46 Since at least the 1990s, tobacco companies have closely monitored these stores and how easily they can be accessed by residents of neighboring states.46–48 Tax differential stores feature extensive manufacturer promotions49,50 and are exempt from typical display requirements due to the expectation that much of the customer-traffic will be drive-through.51 Tax differential stores were listed by Lorillard in its internal documents as eligible for “niche” promotions that increase store incentives, along with “Indian Reservations,”52 if “primary business is by the carton”49 and they sold at least 30 cartons per week.53–55

Both Philip Morris and RJ Reynolds direct increased promotions to border stores in lower-tax jurisdictions after tax increases in neighboring states, to reduce their already-lower prices.56–58 In 1994, Lorillard’s “Buydown” promotions for tax differential stores ranged from $1 to $3, depending on brand.53 In 2000, RJ Reynolds drafted a letter for New York State retailers to use when lobbying against statewide regulation of manufacturer incentives which explained that buydowns are “payments made by or on behalf of a manufacturer… to reduce the cost of cigarettes to an agent, wholesaler or retailer” that “reduce the cost of cigarettes to consumers.”59 According to the letter, retailers preferred buydowns “over coupons because the immediate payment … avoids the retailer cash flow problems created by the time lag between coupon acceptance and redemption.”59

Industry Claims Made to Lobby Against Tax Increases

The tobacco industry lobbies extensively to prevent significant tobacco tax increases.60 In the 1990s, Philip Morris commissioned at least 12 reports to advocate against proposed state tobacco tax increases.61 Philip Morris hired the consulting firm InContext Inc., which had previously prepared arguments against other tobacco control policies, to assess retail sales on opposite sides of state “tax differential” borders.62–69 The target audiences included “state legislators”64,66 and other “state government policy makers”64–66 as well as “state-wide and local media.”64 Although the reports were presented as location-specific, the same claims were repeated for each region, in some cases verbatim.64–66 In every case, InContext claimed that the region under review had existing tobacco retailers who were economically vital and needed to be protected from competitors in lower-tax neighboring states by leaving tobacco taxes at their existing levels.44,64–74 The reports claimed that “retail tax disparities have skewed job, businesses, and prosperity… in favor of the low tax state.”64 As planned, these reports were subsequently quoted by local media.75–81

These InContext lobbying documents claimed that distance affected users’ ability to take advantage of tax differentials, and specifically in Washington State that “the highest [local] taxes are… where distance from [the] border holds those areas harmless from retail sales competition.”64 InContext argued that the distance consumers were willing to travel increased with the size of the tax differential and existing commute and vacation patterns; the distance they proposed shoppers were willing to travel increased with every report, from an initial 5 miles to 100 miles.64,66,73,82 They further argued that decisions to cross tax differential borders for lower-priced cigarettes were “irreversible”65 and quoted tax differential store owners who claimed that 30–95% of their customers were from higher-tax areas.65 Similarly, a 1998 lobbying document commissioned by Philip Morris from the American Economics Group to argue against a tobacco tax increase in New Hampshire estimated that the state’s tax differential stores retained sales of over 2 million packs each year from tobacco users visiting from surrounding states with higher taxes.83

Internal Industry Analyses of the Actual Effects on Tax Differential Store Sales After State Tobacco tax increases

In May 1989, New York State implemented a 12 cent per pack tax increase (from 21¢ to 33¢), which the Philip Morris Marketing Information and Analysis Division estimated reduced their “pre-tax increase trend [in sales]” by 1.2% annually as of July 1990.84 The same analysis concluded that between 1989 and 1990, 7 states on the east coast had increased their tobacco taxes by 3¢ to 12¢ per pack (10%–57% of prior prices), nonetheless, “due to differences in timing and volume … sales trends for the Region do not exhibit a clear impact from the tax increases.”84

In 1993, Massachusetts increased its tobacco tax by 25¢ (from 26¢ to 51¢).30 InContext’s publicly released reports for Philip Morris had estimated that tax differential stores in New Hampshire increased their sales by 11–36%.44 Philip Morris internal Region 1 (the US Northeast) Monthly Highlights reported that after the 1993 Massachusetts tax increase, “volume shifts have been observed in Southern Vermont retail outlets due to migration of Massachusetts smokers across state lines for purchasing purposes” but did not specify percentages.85 A sales analysis of Rhode Island border stores showed sales increases ranging from 27% to 200%.85 However, at the same time, Philip Morris found that cross-border sales to Canadians were decreasing due to the Canadian government’s increased enforcement of duty laws.85 A 1994 internal memo for Lorillard executives analyzing the 1993 Massachusetts tax effects on sales concluded that the tax increase “created a 6% decline [in wholesale]” and that “part of the decline in Massachusetts was offset by gains in bordering states,”86 although it did not detail how much.

A similar Lorillard memo discussing the 1994 Michigan 50¢ (25¢ to 75¢) state tax increase estimated that only 18% of the reduced sales in Michigan were “offset by gains in border stores in Indiana and Ohio.”87 Four months after the 1994 Michigan tax increase, Philip Morris reported that the company expected sales to decrease by 11–13% and found they had decreased by 10%, with no shift from “premium” to “discount” brands and despite increased sales in neighboring lower tax jurisdictions.88

A study of smokers conducted for Lorillard after Michigan’s 1994 tax increase found that the company had successfully shifted some of its customers to tax differential stores, and that while some had quit after the tax increase, those that continued to smoke had not reduced their numbers of cigarettes.89 A study conducted for RJ Reynolds on sales in Michigan after the same tax increase noted that, “Full Price has actually gained share throughout Michigan … this is likely due to the Full Price promotions [RJ Reynolds] put in place [to] offset the tax increase.”90 Overall, Lorillard reported that despite efforts to convince consumers to shop at lower-tax sales outlets “any ‘sizeable’ tax increase in a state [such as Michigan’s] will result in a 7% cutback in consumption.”87 The executives concluded that given their inability to shift people to purchase tobacco in lower-tax areas, “in the event of a… tax increase… [we should] offset our share of a consumption decline by taking [volume] away from our competition.”87 In 1996 RJ Reynolds conducted a phone-interview survey of 1,856 smokers through Woeflel Research to assess “cigarette outlets,” (including border stores) which represented “10% of industry volume” and consumed 28 % of [all industry] promotional support.45 The study determined that consumers who used outlet stores were older and less educated, and driven by price—85% purchased by carton rather than by pack.45

Price promotions became more critical to the industry after the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement ended many traditional marketing strategies such as advertising on billboards.91 In 2000, New York State increased its tobacco tax by 55¢ ($0.56 to $1.11). Two months later Lorillard executives stated that “Native American” store sales in New York had increased by over 50%.92 While there are reports of smuggling after tax increases that reduces consumer costs,93 the Lorillard internal analysis reported no smuggling and that border stores saw no change in sales.92 In a letter drafted for retailers to send to state regulators by RJ Reynolds, the company complained the New York tax increase was problematic because the New York Department of Taxation and Finance had decided to prohibit all buydowns, limiting tobacco companies’ ability to undercut the tax increase.59 In the 1990s, tobacco industry reports created to lobby state policymakers had claimed that users would travel extreme distances to purchase tobacco in lower-tax neighboring states.44,64–74 In contrast, Lorillard found that in 2000, after California passed a 50¢ tax increase (37 to 87¢) and the federal tobacco tax increased by 10¢, California tobacco users did not travel to lower-tax neighboring states.94

In summary, the tobacco industry publicly predicted that tobacco tax increases would lead to smuggling across state lines and users making a permanent choice to purchase tobacco in lower-tax jurisdictions. In contrast, internal documents the companies recognized that tobacco tax increases did not result in smuggling and that efforts to convince users to purchase in lower-tax jurisdictions were less successful than intended. Independent analyses found that those tobacco users who initially shifted their purchases to lower-tax jurisdictions became less willing to do so over time.

Company Pricing Responses to Tax Increases: Undershifting and Overshifting

In the wake of a tax increase, tobacco manufacturers have choices about how to change prices. Smokers can bear the full cost of the tax so that the price per pack increases by the amount of the tax, the companies can “undershift” the tax by cutting wholesale prices so that the total retail price increases by less than the amount of the tax to buffer the effect of the tax increase on consumers, or the tax can be “overshifted” so that the price increases by more than the amount of the tax in order to maintain company cash flow (and profits) in the face of the consumption decline caused by the price increase. After the 1983 US federal tax doubled from 8¢ to 16¢, tobacco companies overshifted, raising prices by more than the amount of the tax which masked the source of the simultaneous wholesale price increase to consumers.29 Four years later, an executive memo at Philip Morris discussing how to respond to tobacco tax increases explained that, “the [US] 1982–83 round of price increases [when the company raised prices more than the tax increases] caused two million adults to quit smoking and prevented 600,000 teenagers from starting to smoke … We don’t need to have that happen again.”95 Despite this concern, tobacco companies have taken varying pricing approaches in response to increased taxes.

Tobacco taxes as a percentage of existing prices have increased over time in the US: increases averaged 35% in the 1980s, 48% in the 1990s, and 114% from 2000 to 2014.30 Throughout the 1990s, states mostly increased their tobacco taxes by a few cents per pack, but between 2000 and 2016, 11 states increased their tobacco taxes by more than $1 in a single year.30 Other states substantially increased taxes over multiple years: between 2002 and 2012 Hawaii’s tobacco tax increased from $1 per pack to $3.20 per pack and between 2005 and 2014 Minnesota’s tobacco tax increased from 48¢ per pack to $3.34 per pack.30 Localities have imposed steep increases as well; Cook County, IL raised its tobacco tax by $1 in 2012 to $3, and NYC set a minimum pack price of $13 in 2018.

In 1994, Michigan increased its tax by 50¢ (200% increase, from 25¢ to 75¢ per pack). This tax appears to have been passed on unchanged; a sales report from Philip Morris explained that while the company had initially planned to change its pricing by not only passing on the full tax, but adding a “25% margin” it ultimately chose not to overshift, although no explanation for the decision was provided.88 Its choice was consistent with those of other tobacco companies; an RJ Reynolds sales report summarized that “Effective May 1, 1994, Michigan increased its excise tax on cigarettes by 50¢ a pack… From a review of retail prices, it appears that retailers continue to pass the full 50¢ tax on to consumers.”90

A modification of undershifting taxes is to make them less visible by sandwiching manufacturer price increases between relatively small tax increases. New Hampshire price increases provide an example. In 1999 the state increased its tobacco tax by 15¢ (60% increase, from 25¢ to 37¢). RJ Reynolds responded by increasing wholesale prices by smaller amounts in subsequent years; the manufacturer price increase was 45¢ in 1998, then 18¢ in 1999 when the state tobacco tax increased by 15¢ (for a total increase of 33¢,) then 13¢ in 2000 when the federal tobacco tax increased by 10¢ (for a total increase of 23¢).96

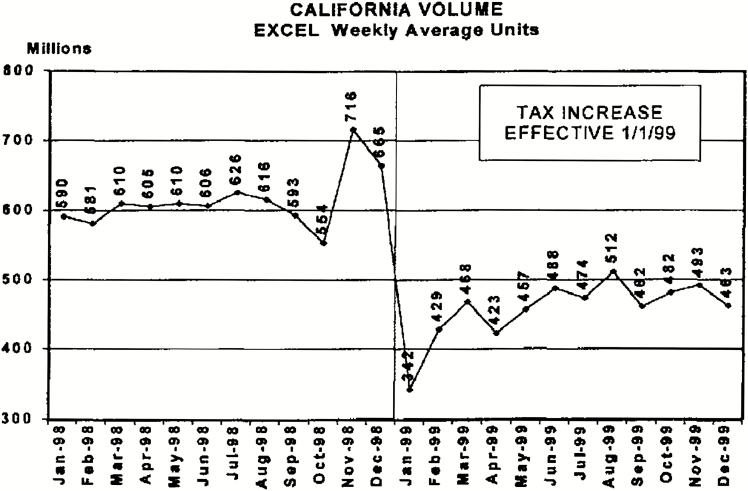

Undershifting taxes by modifying manufacturer price increases appears more difficult for tobacco companies when tax increases are higher. In 1999, California increased its state tobacco tax by 50¢ (135% increase, from 37¢ to 87¢) and in 2000, the federal tobacco tax increased by 10¢ (from 24¢ to 34¢ per pack). Lorillard found that when the combined federal and California state tax increases were passed on to consumers sales dropped (Figure 1).94 In 2014, Minnesota increased its tobacco tax by $1.74 (109% increase, from $1.60 to $3.34);30 contemporaneous independent research found that retail prices overshifted in response, increasing by $1.89.22

Figure 1.

Lorillard’s California sales volume report after a 45¢ federal tax increase followed immediately by a 50¢ California tax increase.94

Discussion

Consistent with previous research,97,98 the internal documents that we examined indicate that tobacco companies attempt to reduce the public health benefits of tobacco increases. Industry strategies extend beyond previously described14–21 coupons provided to consumers and the creation of discount brands into efforts to modify shopping patterns by promoting sales in tax differential or border stores, and shifting manufacturer pricing.

Lobbying documents produced by the tobacco industry argue that tax increases are ineffective because retailers will smuggle tobacco into high-tax areas and consumers will travel to lower-tax jurisdictions to purchase them. The companies’ internal sales reports in the wake of tobacco tax increases reveal that these claims are significantly overstated: none of the industry’s internal reports following the tax increase found evidence of smuggling after tax increases. Tobacco companies have, however, devoted extensive efforts to convincing consumers to travel to lower-tax jurisdictions, including border store specific promotions. Our findings drawn from tobacco industry sales reports suggest that promotions focused on border stores have partially undercut the use of tobacco taxes intended to increase prices by encouraging some users to purchase tobacco across state lines. Reports commissioned by the tobacco industry provide inconsistent expectations regarding how far consumers might be expected to travel, ranging from 5 to 100 miles; given that these reports were intended for lobbying, the actual distance users are willing to travel remains unclear.44,64–74

Although the willingness of tobacco users to travel to lower-tax jurisdictions appears to decline over time, public health regulators could make tobacco tax increases more effective in the short term. New York’s decision to eliminate buydowns made it more difficult to undercut the state’s 2000 tobacco tax increase and Canadian enforcement of duty on tobacco purchases made in the United States reduced cross-border sales. Seven years after the New York tax increase, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) concluded that initial tax-avoidant purchases (i.e. residents crossing to lower-tax jurisdictions) in New York dropped after 2 years, but tobacco company discounts had undercut the new tax, so that the 32% price increase that would have occurred had the full cost of the tax been passed through to consumers without discounts was a 20% increase in practice.4 A contemporaneous independent study using scanner sales data found that retail promotions were targeted to high tax areas had similar effects: tobacco industry efforts to undercut price increases following tax increases were not fully realized in higher prices and promoted sales were increasing over time.99 Similarly, public health researchers suggest using minimum price laws to limit the effects of price promotions.97,98,100,101 These interventions also have the potential to reduce coupon use.

In addition to promoting border store sales, tobacco companies have modified manufacturer wholesale prices to undercut the effects of higher taxes that were intended to increase prices and reduce prevalence. Research on alcohol taxes suggests that only some increases are completely passed on to consumers.102 When tax increases are small, alcohol sellers undershift the tax and do not increase prices; in the face of small tax increases, alcohol prices are “sticky,” or resistant to change.102 When tax increases are large, alcohol sellers overshift the tax, increasing retail prices by more than the amount of the tax.102 Our results suggest that tobacco manufacturers behave similarly to alcohol manufacturers in that they undershift smaller tax increases and overshift larger tax increases. Independent research in the UK found that tobacco companies also undershifted discount brands and overshifted higher price brands after tax increases.97,98 Taken together these findings suggest that passing large tax increases that take effect immediately will reduce tobacco use more than spreading smaller tax increases over a longer time. A recent complication is the rapid development of new non-cigarette tobacco products that are taxed at lower rates, leading consumers to substitute: expanding excise taxes to all tobacco products is also critical to reducing consumption.27

Limitations

Tobacco industry documents, by their nature, provide incomplete information about corporate activity. Some potentially relevant documents were marked as confidential or privileged communication; tobacco companies use these claims as a strategy to avoid making internal documents public.103,104 While our findings suggest that tobacco companies deliberately target promotions and price changes to limit the effect of taxes on tobacco use, this is not necessarily the case for every promotion or pricing change after a tax increase. There is limited research on the distribution of promotions and changes in pricing before and after tax increases; future studies that track and archive these data would be useful to both regulators and researchers.

Public Health Implications

There has been little public health research on the ways that tobacco companies use “invisible” strategies to promote tobacco products in the wake of tax increases. Internal tobacco industry documents suggest that tobacco companies have found strategies to partially blunt the effects of tax increases that were intended to increase prices and reduce the prevalence of tobacco use. Tobacco companies have used promotions directed at retail stores near the borders of states with tax differentials (and Tribal Lands)52 to encourage users, particularly those near lower-tax jurisdictions, to purchase where taxes are lower, reducing the cost of use. Similarly, they have changed manufacturer pricing to hide tax increases that take effect over time from consumers. Policymakers should address these efforts to undercut public health interventions by implementing minimum pricing restrictions97,98,100,101 as well as regulating tobacco industry promotions to wholesalers and retailers and passing tax increases that are large, immediate, and cover all tobacco products.

Author Contributions

DA and SG conceived and designed the paper, interpreted the results, reviewed and revised the manuscript in preparation for publication, and read and approved the final manuscript. DA wrote the first draft.

Funding

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute (grants CA-087472, CA-140236, and TRDRP 26IR-0014). The funders played no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Cancer Institute, World Health Organization. The Economics of Tobacco and Tobacco Control. Bethesda, MD and Geneva, Switzerland: National Institutes of Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peterson DE, Zeger SL, Remington PL, Anderson HA. The effect of state cigarette tax increases on cigarette sales, 1955 to 1988. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(1):94–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Decline in smoking prevalence—New York City, 2002–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(24):604–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking before and after an excise tax increase and an antismoking campaign—Massachusetts, 1990–1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45(44):966–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chaloupka FJ, Cummings KM, Morley CP, Horan JK. Tax, price and cigarette smoking: Evidence from the tobacco documents and implications for tobacco company marketing strategies. Tob Control. 2002;11(Suppl 1):I62–I72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tobacco Control Legal Consortium. Price-Related Promotions for Tobacco Products: An Introduction to Key Terms & Concepts. Public Health Law Center at William Mitchell College of Law;St. Paul: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pierce JP, Gilmer TP, Lee L, Gilpin EA, de Beyer J, Messer K. Tobacco industry price-subsidizing promotions may overcome the downward pressure of higher prices on initiation of regular smoking. Health Econ. 2005;14(10):1061–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Public Health and Tobacco Policy Center. Tobacco Price Promotion: Policy Responses to Industry Price Manipulation. Boston: Northeastern University School of Law; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Federal Trade Commission. Cigarette Report for 2004 and 2005. Washington, DC, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Federal Trade Commission. Cigarette Report for 2014. Washington, DC, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Federal Trade Commission. Federal Trade Commission. Washington, DC, 2018:35. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Federal Trade Commission. Smokeless Tobacco Report for 2016. Washington, DC, 2018:39. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pesko MF, Kruger J, Hyland A. Cigarette price minimization strategies used by adults. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):e19–e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hyland A, Higbee C, Bauer JE, Giovino GA, Cummings KM. Cigarette purchasing behaviors when prices are high. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004;10(6):497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hyland A, Bauer JE, Li Q, et al. Higher cigarette prices influence cigarette purchase patterns. Tob Control. 2005;14(2):86–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bound J, Lovenheim MF, Turner S. Why have college completion rates declined? an analysis of changing student preparation and collegiate resources. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2010;2(3):129–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Choi K, Hennrikus D, Forster J, St Claire AW. Use of price-minimizing strategies by smokers and their effects on subsequent smoking behaviors. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(7):864–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. White VM, Gilpin EA, White MM, Pierce JP. How do smokers control their cigarette expenditures? Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(4):625–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Choi K, Hennrikus DJ, Forster JL, Moilanen M. Receipt and redemption of cigarette coupons, perceptions of cigarette companies and smoking cessation. Tob Control. 2013;22(6):418–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lewis MJ, Delnevo CD, Slade J. Tobacco industry direct mail marketing and participation by New Jersey adults. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(2):257–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brock B, Choi K, Boyle RG, Moilanen M, Schillo BA. Tobacco product prices before and after a statewide tobacco tax increase. Tob Control. 2016;25(2):166–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Slater S, Chaloupka FJ, Wakefield M. State variation in retail promotions and advertising for Marlboro cigarettes. Tob Control. 2001;10(4):337–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu X, Wang X, Caraballo RS. Is every smoker interested in price promotions? an evaluation of price-related discounts by cigarette brands. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22(1):20–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Atuk O, Özmen MU. Firm strategy and consumer behaviour under a complex tobacco tax system: Implications for the effectiveness of taxation on tobacco control. Tob Control. 2017;26(3):277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bayly M, Scollo M, White S, Lindorff K, Wakefield M. Tobacco price boards as a promotional strategy-a longitudinal observational study in Australian retailers. Tob Control. 2018;27(4):427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gourdet CK, Chriqui JF, Leider J, DeLong H, Goodman C, Chaloupka FJ.. Tobacco Product Taxation: An Analysis of State Tax Schemes Nationwide, Selected Years, 2005–2014. Chicago, IL: Institutes for Health Research and Policy, School of Public Health, University of Illinois at Chicago; August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Black AP. How a Gas Tax Increase Affects the Retail Pump Price: An Economic Analysis of 2013–14 Market Impacts in 5 States. Washington, DC: : American Road & Transportation Builders Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Harris J. The 1983 Increase in the Federal Cigarette Excise Tax. Tax policy and the Economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Walker O. The Tax Burden on Tobacco. Atlanta, GA: : US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee JGL, Richardson A, Golden SD, Ribisl KM. Promotions on Newport and Marlboro cigarette packages: A national study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(10):1243–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Truth Tobacco Industry Documents. University of California, San Francisco; 2018. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/. Accessed May 10, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wieland LS, Rutkow L, Vedula SS, et al. Who has used internal company documents for biomedical and public health research and where did they find them? PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e94709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Malone RE. UCSF’s new center for tobacco control research and education finds valuable lessons in the tobacco industry’s internal documents. J Emerg Nurs. 2003;29(1):75–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Balbach ED, Gasior RJ, Barbeau EM. Tobacco industry documents: Comparing the Minnesota Depository and internet access. Tob Control. 2002;11(1):68–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Malone RE, Balbach ED. Tobacco industry documents: Treasure trove or quagmire? Tobacco Control. 2000;9:334–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bero LA. Implications of the tobacco industry documents for public health and policy. Annu Rev Public Health. 2003;24(3):3.1–3.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Glantz SA, Barnes DE, Bero L, Hanauer P, Slade J. Looking through a keyhole at the tobacco industry. The Brown and Williamson documents. JAMA. 1995;274(3):219–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Van Maanen J, Dabbs JM, Faulkner RR.. Varieties of Qualitative Research. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 4th ed.Beverly Hills: Sage; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41. The Perspective of PM International on Smoking and Health Issues. March 29, 1985. Philip Morris Records https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/lpgv0125

- 42. General Comments on Smoking and Health. March 1985. Philip Morris Records https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/nzcp0124.

- 43. Reindel SJ, Williams JF.. Lorillard. Promotions - Newport $3.00 $4.00 Carton Promotion Native American Tax Differential 990400 - 990600 <99-006a> <99-007a>. January 22, 1999. Lorillard Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/pjdg0152. [Google Scholar]

- 44. InContext Inc., New England Convenience Store Association. Massachusetts v. New Hampshire Cross Border Retail Sales Comparison Change in Retail Sales 1993–1994. June 20, 1996. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/hmfh0085. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Woelfel Research. Background/Objectives. Cigarette Outlets, Consisting of Cigarette Stores, Border Stores, and Reservation Stores, Represent 10 of Industry Volume and This New Format Is Expected to Grow. 1996. RJ Reynolds Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/fycn0091. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Red Book 1995 Changes. August 11, 1994. Lorillard Records https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/rgcp0010.

- 47. Philip Morris. High Tax Differential Borders. 1992. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/jsyv0152. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tsigrikes P. Lorillard. Kent Monthly Volume Report - April 1996. May 10, 1996. Lorillard Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/yygk0076. [Google Scholar]

- 49. F.D.A. - Lorillard Merchandising Package Carton Merchandising. November 20, 1996. Lorillard Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/pqxc0011. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Style 1997 Brand Plan - Update II. April 15, 1997. Lorillard Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/jkjf0024. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zolot SP. Promotional Allowance Program. May 1996. Lorillard Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/jfvh0003. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lempert LK, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry promotional strategies targeting American Indians/Alaska natives and exploiting tribal sovereignty. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2018. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntz048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Generic/PL Promotions. 1994. Lorillard Records https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/qrhg0013.

- 54. Enloe SL. Merchandising – Excel – C5. January 16, 1998. Lorillard Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/ktld0152. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Caldarella RW. Merchandising – Cigarette Outlet Survey. January 29, 1998. Lorillard Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/pkkd0067. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Revised Promotion Alert. Camel. Maine State Excise Tax Coupon Mailing. October 21, 1997. RJ Reynolds Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/ythk0003. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Neidle B., Morris P. Massachusetts Excise Tax Hike. November 12, 1992. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/mnhc0007. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Curry M., Reynolds R. Options to Address Minnesota 15 Cents Excise Tax Increase. May 27, 1987. RJ Reynolds Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/lxgg0077. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cigarette Buydown Ban in New York State. March 24, 2000. RJ Reynolds Records https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/knjk0091.

- 60. Smith KE, Savell E, Gilmore AB. What is known about tobacco industry efforts to influence tobacco tax? A systematic review of empirical studies. Tob Control. 2013;22(2):144–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Philip M, Byerley J.. 1996 Original Budget (State Government Affairs Transfer). 1996. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/xzjv0226. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ritch WA, Begay ME. Strange bedfellows: The history of collaboration between the Massachusetts Restaurant Association and the tobacco industry. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(4):598–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Comments Sent to FDA. August 10 1995. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/mnyv0063. [Google Scholar]

- 64. InContext Inc., Defranco LJ, Lilley W III. Oregon Vs. Washington Cross-Border Retail Tax Differentials and Cross-Border Retail Job Disparities and Retail Sales Disparities October 14, 1996. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/pklh0061. [Google Scholar]

- 65. InContext Inc., Defranco LJ, Lilley W III. Philip Morris Management Corp., Wisconsin Merchants Federation Michigan, Illinois, Iowa, and Minnesota: The Economic Impact of Excise Taxes on Jobs in Wisconsin; April 28, 1997. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/mffn0085. [Google Scholar]

- 66. InContext Inc., Defranco LJ, Lilley W III. Geo-Political Economic Impact of Excise-Tax-Sensitive Jobs on the Florida Panhandle March 20, 1997. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/hjfl0063. [Google Scholar]

- 67. InContext Inc., Defranco LJ, Lilley W. Economic Impact of Retail Taxes in Delaware December 15, 1997. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/srbk0057. [Google Scholar]

- 68. InContext Inc., Defranco LJ, Lilley W III. Economic Impact of Excise-Tax-Sensitive Jobs Along the Washington-Oregon Border. March 21, 1997. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/thvf0068. [Google Scholar]

- 69. InContext Inc., Defranco LJ, Lilley W III. Impact of Retail Taxes on the Illinois – Indiana Border. July 16, 1996. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/flhk0057. [Google Scholar]

- 70. InContext Inc., Defranco LJ, Lilley W III. Geo-Political Analysis of Excise-Tax-Sensitive Jobs: U.S. Northern Tier States Vs. Canada. November 18, 1997. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/zhgn0085. [Google Scholar]

- 71. InContext Inc., Defranco LJ, Lilley W III. Cigarette Taxes and Retail Jobs in the Cornbelt with a Special Analysis of Nebraska’s 66 Cents Proposed Cigarette Tax Increase and Consequent Job Loss April 5, 1999. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/gthw0080. [Google Scholar]

- 72. InContext Inc., Defranco LJ, Lilley W III. Association NECS. Geographic and Political Distribution of Retail Jobs Along the Massachusetts Northern Tier: Before and after, 1993 through 1996, the State Legislative Perspective June 20, 1996. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/ljfj0064. [Google Scholar]

- 73. InContext Inc., Defranco LJ, Lilley W III. Retail Merchants Association of New Hampshire. Geographic and Political Distribution of Cross-Border Jobs in New England (Including Canada). January 26, 1996. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/kmlk0057. [Google Scholar]

- 74. InContext Inc., Defranco LJ, Lilley W III. Geographic and Political Distribution of Tobacco-Related Jobs in San Diego. May 1998. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/fgxf0066. [Google Scholar]

- 75. New Tax Study Shows Massachusetts Border Communities Are Losing Jobs and Retail Sales to New Hampshire and Vermont. January 1997. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/gnjw0104. [Google Scholar]

- 76. New Hampshire Sunday News. Study: Taxes Give NH the Retail Advantage - Wealth and Jobs Tend Flow toward Lowest Tax. February 4, 1996. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/jggk0053. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Haverhill G, Prussman TA.. Are Local Dollars Falling Off the ‘Cliff?’. July 2, 1996. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/slkk0057. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kaupp J. State Grapples with Tax Dilemma. May 26, 1996. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/ksww0080. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Daily News, Salemi T.Study Shows Valley Losing Business to N.H. July 2, 1996. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/qrkk0057. [Google Scholar]

- 80. New Study Finds Job Creation and Household Income in New England Linked to State Excise Taxes. February 1996. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/kggk0053. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Massachusetts Restaurant Association. Model Legislative Communications Plan. 1997. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/fhgh0167. [Google Scholar]

- 82. DeFranco LJ, Lilley W, Dunham JR. The case of the transient taxpayer: How tax-driven price differentials for commodity goods can create improbable markets. Bus. Econ. 1998;33(3):43–49. [Google Scholar]

- 83. The Likely Economic Consequences from Raising New Hampshire’s Cigarette Excise Tax by 23 Cents Per Pack. 1998. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/hmmy0090. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Neidle B. Region 1 Review. July 18, 1990. Philip Morris Records https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/jkdb0067.

- 85. Monthly Region Highlights 930200. February 1993. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/glbd0012. [Google Scholar]

- 86. McFadden P. Tax Increase – Massachusetts. October 18, 1994. Lorillard Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/hmgb0011. [Google Scholar]

- 87. McFadden P. Tax Increase – Michigan. October 20, 1994. Lorillard Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/zlgb0011. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Philip Morris. Michigan State Excise Tax – Sixteen Week Overview Changes in Sales Activity through 940820.; N698. August 20, 1994. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/hzhp0090. [Google Scholar]

- 89. SE Surveys. A Study of the Effect of Pricing Changes in Michigan Two Months after Tax Increase (Mpid Number 5549/294). August 1994. Lorillard Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/ymkh0013. [Google Scholar]

- 90. Petto FG. Michigan Tax Increase. October 17, 1994. RJ Reynolds Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/hzbn0095. [Google Scholar]

- 91. National Association of Attorneys General. Master Settlement Agreement. 1998:88. [Google Scholar]

- 92. Todd D. New York State Excise Tax Increase. May 15, 2000. Lorillard Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/qzjy0094. [Google Scholar]

- 93. Davis KC, Grimshaw V, Merriman D, et al. Cigarette trafficking in five northeastern US cities. Tob Control. 2014;23(e1):e62–e68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Todd D. California Cigarette Tax Increase. February 4, 2000. Lorillard Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/slnn0094. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Johnston ME., Morris P. Philip Morris USA Inter-Office Correspondence Regarding: Handling an excise tax increase. September 25, 2000. Philip Morris Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/kngv0184. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Powers DM, Tompson R.. Price Increases, Tax Increases, Etc. January 31, 2000. RJ Reynolds Records; https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/zspk0020. [Google Scholar]

- 97. Gilmore AB, Tavakoly B, Taylor G, Reed H. Understanding tobacco industry pricing strategy and whether it undermines tobacco tax policy: The example of the UK cigarette market. Addiction. 2013;108(7):1317–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Hiscock R, Branston JR, McNeill A, Hitchman SC, Partos TR, Gilmore AB. Tobacco industry strategies undermine government tax policy: evidence from commercial data. Tob Control. 2018;27: 488–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Loomis BR, Farrelly MC, Mann NH. The association of retail promotions for cigarettes with the Master Settlement Agreement, tobacco control programmes and cigarette excise taxes. Tob Control. 2006;15(6):458–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Tobacco Control Legal Consortium. Cigarette Minimum Price Laws. St. Paul, MN: Public Health Law Center at William Mitchell College of Law; July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 101. DeLong H, Chriqui JF, Leider J, Chaloupka FJ.. Tobacco Product Pricing Laws: A State-by-State Analysis, 2015. Chicago, IL: Tobacconomics Program, Institute for Health Research and Policy, School of Public Health, University of Illinois at Chicago;2016. [Google Scholar]

- 102. Conlon CT, Rao N.. Discrete Prices and the Incidence and Efficiency of Excise Taxes (June 17, 2016). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2813016. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2813016 [Google Scholar]

- 103. LeGresley EM, Muggli ME, Hurt RD. Playing hide-and-seek with the tobacco industry. Nicotine Tob. Res.. 2005;7(1):27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. LeGresley E, Lee K. Analysis of British American Tobacco’s questionable use of privilege and protected document claims at the Guildford Depository. Tobacco Control. 2017;26(3):316–322. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-052955. Epub 2016 Jun 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]