Abstract

Purpose:

Describe trial design and baseline characteristics of participants in the DRy Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM©) Study.

Design:

Prospective, multi-center, randomized, double-masked “real-world” clinical trial assessing efficacy and safety of oral omega-3 (ω3) supplementation for the treatment of dry eye disease (DED).

Methods:

Setting: Multi-center study (27 sites) consisting of academic and private practices led by ophthalmologists and optometrists throughout the United States.

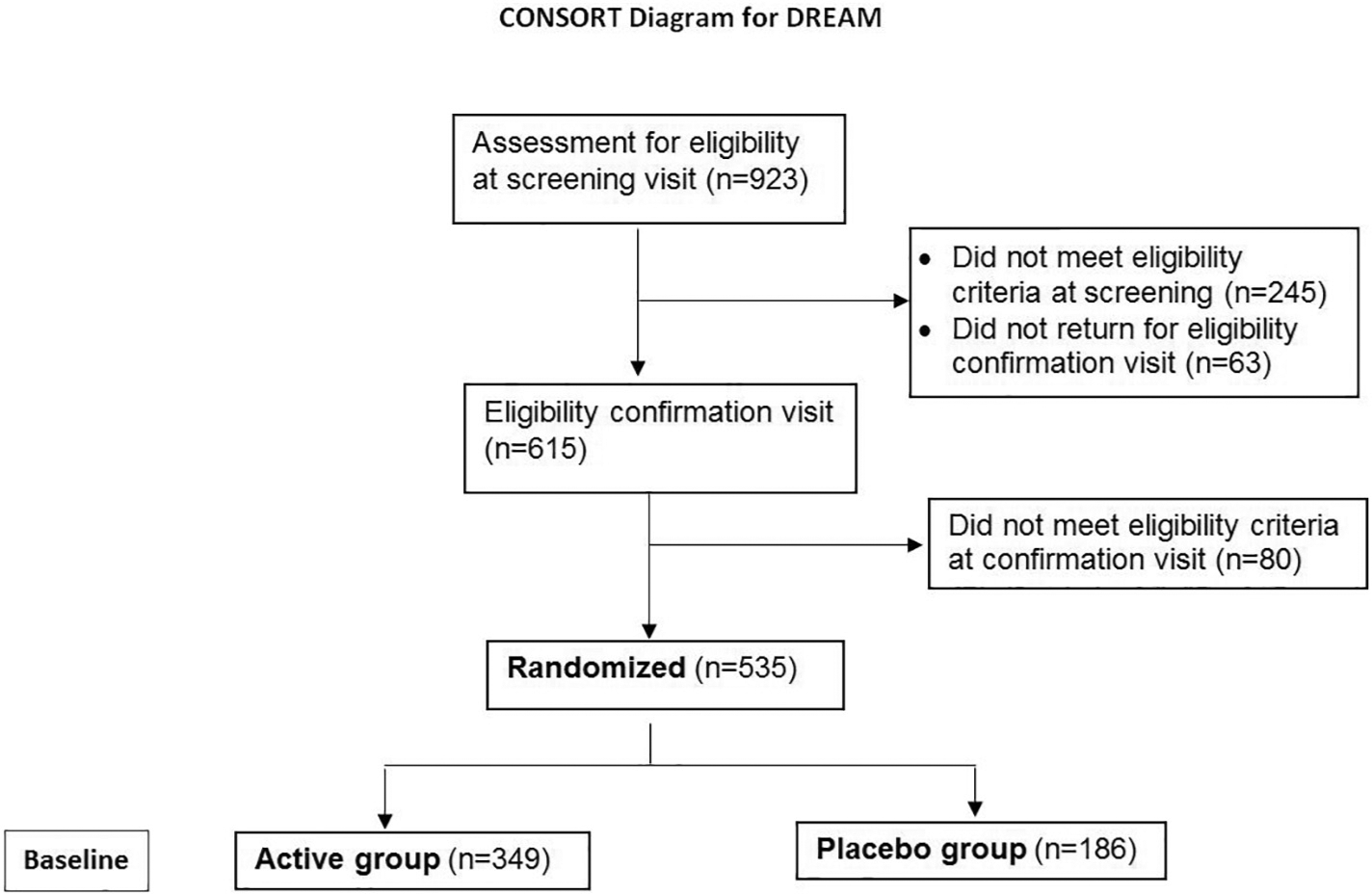

Study Population: 535 subjects with symptoms and signs of moderate to severe DED were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to ?3 or placebo. All participants, clinical staff, and laboratory personnel were masked to treatment assignment.

Intervention: 3000 mg ω3 (2000 mg eicosapentaenoic acid(EPA) and 1000 mg docosahexaenoic acid(DHA)) per day or placebo (5000 mg olive oil per day)

Primary Outcome: Change in dry eye symptoms (change from baseline to follow-up in the Ocular Surface Disease Index(OSDI) score).

Results:

Mean age of participants was 58.0 ± 13.2 years. Mean OSDI score at baseline was 44.4 ± 14.2. Mean conjunctival staining score (scale 0–6) was 3.0 ± 1.4, corneal staining score (scale 0–15) was 3.9 ± 2.7, tear break-up time was 3.1 ± 1.5 s, and Schirmer test was 9.6 ± 6.5 mm/5 min.

Conclusions:

DREAM© participants mirror real world patients who seek intervention for their DED-related symptoms despite their current treatments. Results regarding the efficacy of omega-3 supplementation will be helpful to clinicians and patients with moderate to severe DED who are considering omega-3 as a treatment. This trial design may be a model for future RCT’s on nutritional supplements and DED treatments seeking to provide useful information for clinical practice.

Trial registration:

Clinicaltrials.gov number NCT02128763.

Keywords: Dry eye disease, Omega-3 fatty acid, Clinical trial design, Baseline characteristics, Inflammation, Nutritional trial design

1. Introduction

Dry eye disease (DED) is a multifactorial condition that causes symptoms of ocular discomfort, fatigue, and visual disturbance that interfere with quality of life, and can be described as a chronic pain syndrome [1, 2]. DED affects approximately 14% of adults in the United States [3] and is one of the most common reasons patients seek eye care treatment [4, 5].

The economic burden of DED is significant. The average cost of DED is estimated to be over $59 billion to the US society overall per year, taking into account both healthcare costs and loss of productivity costs [6]. In addition, DED presents an unmet medical need where current treatments are inadequate and expensive. Better treatments are needed that target the underlying pathophysiologic causes of the disease.

Although the pathogenesis of DED is not fully understood, it is recognized that inflammation has a prominent role in its development and chronicity [7, 8]. Regardless of the instigating etiology, DED eventually leads to inflammation of the ocular surface via various mechanisms leading to ocular surface damage and further exacerbation of DED inflammatory processes, thus creating a self-perpetuating vicious cycle of inflammation and DED [8]. Anti-inflammatory therapies may break this cycle of DED and chronic inflammation [9]. Clinicians and their DED patients continue to seek better methods to control inflammation and often are particularly attracted to “natural” treatments, such as nutritional supplements like omega-3 fatty acids (ω3).

Clinical trials on the role of poly-unsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in various inflammatory diseases have shown anti-inflammatory benefits of supplementation with ω3 PUFAs [10–15]. However, the evidence for the efficacy of ω3 for treating DED is inconsistent, and the studies were of short duration, often had small sample sizes, or were not representative of the general DED population due to restrictive eligibility criteria [9, 16]. Larger, long-term studies with objective measures of compliance are needed to clarify whether or not ω3 supplements are effective and safe for the treatment of DED given that ω3 is normally used on a long term basis. To address this need, the Dry Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM©) Study was carefully designed to provide reliable data on the safety and efficacy of ω3 for the treatment of DED and at the same time improve our understaning of DED. In addition, the methods used in this DED protocol can be applied to other trials to evaluate safety and efficacy of nutritional supplements. Key methodological issues in the protocol design for DREAM© are discussed.

2. Methods

2.1. Overview of trial design

The DREAM© study was a multi-center, double-masked, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial (Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier NCT02128763) that provided evidence on the efficacy and safety of ω3 in DED, as well as longitudinal data over one year of observation on a well-defined cohort of typical DED subjects with moderate to severe DED. A one-year course of treatment was selected to diminish the effects of seasonal changes on DED symptom and signs and also to provide safety information on the long-term use of ω3. A total of 535 patients with DED were enrolled across 27 sites throughout the United States. Subjects were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to ω3 (2000 mg eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), 1000 mg docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) = total 3000 mg ω3 per day) versus placebo (5000 mg olive oil per day) (Fig. 1). Patients were examined at 3, 6 and 12 months. The primary outcome measure was a mean change in symptoms as measured by the Ocular Disease Surface Index (OSDI) from baseline compared to 6 and 12 months. The DREAM© study protocol and informed consent were approved by the respective clinical center institutional review boards or a centralized institutional review board (University of Pennsylvania). The DREAM© study was in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and accepted by the US Food and Drug Administration under an investigational new drug (IND) application (IND 106,387).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT Diagram for the DRy Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM©) Study.

2.2. Study treatment

Although various doses have been used in clinical trials to study the role of ω3 supplementation in a variety of diseases [16–30], the dose of 3 g was chosen to achieve a maximal therapeutic effect without added risks, such as bleeding, even when patients were already taking supplements with 1.2 g or less per day of ω3 [31, 32]. A ratio of EPA to DHA of 2:1 was selected because this ratio is found in many natural foods [33, 34], and many studies examining the role of ω3 in DED have used this ratio [16, 17, 35, 36]. Fish oil was chosen over other ω3 sources, such as flaxseed oil, because fish oil is well metabolized in humans and the re-esterified triglyceride form, rather than the ethyl ester form, was chosen because of greater absorption, bioavailability, and stability [37–39]. Participants were instructed to take 5 softgel capsules per day. Each active capsule contained 400 mg EPA and 200 mg DHA, providing a daily dose of 2000 mg EPA and 1000 mg DHA.

Each placebo capsule contained 1000 mg of refined olive oil, which is the most common placebo used in other randomized clinical trials on ω3 supplementation [16, 18, 36, 40–44]. Refined olive oil is much lower in polyphenols as compared to extra virgin olive oil, which is the staple of the Mediterranean Diet. Some studies have shown that polyphenols are the source of the beneficial health effects seen from olive oil [45, 46]. Since the DREAM© placebo is refined olive oil that is low in polyphenols, we did not expect to see an effect on dry eye disease. In addition, the total daily dose of olive oil in DREAM© was 5 g per day, or about 1 teaspoon. Studies testing the benefits of olive oil, usually as part of the Mediterranean Diet, have supplied daily doses of at least 60 g [47], and sometimes as high as 100 g [48], over 20 times higher than the DREAM© placebo. Furthermore, the DREAM© olive oil was 68% oleic acid, an omega-9 fatty acid considered neutral with respect to inflammation. In addition, an objective measurement of systemic fatty acid levels by measuring the levels of fatty acids in erythrocytes (red blood cells) at randomization, 6 and 12 month visits, including oleic acid levels was used to measure how well the fatty acid was incorporated into the body. Overall, this dose of olive oil was expected to act as a true placebo due to oleic acid’s lack of effect on inflammation, the lack of polyphenols in refined olive oil, and the small daily dose compared to the Mediterranean Diet.

Masking flavor and lemon essence was added to both active and placebo gelcaps to maintain masking. Active and placebo capsules both contained 3 mg of vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) as an antioxidant preservative. The manufacturer evaluated several formulations to produce a placebo that was identical in smell and appearance to the active supplement. The dose was reduced or withheld when patients reported side effects or developed a contraindication to the full dose of supplementation. If the side effect or contraindication resolved, the full dose was restarted. Otherwise the participant continued taking the reduced dose or stayed off of the supplement for the remainder of the study.

Capsules were manufactured by Access Business Group, LLC (Ada, MI). Active supplements contained fish oil concentrate in the re-esterified triglyceride form supplied by EPAX Norway AS (Alesund, Norway) and derived primarily from mackerel and anchovy. Content of the active and placebo capsules was verified by an independent laboratory (Nutrasource Diagnostics Inc., Guelph, Ontario). The Investigational Drug Service of the University of Pennsylvania distributed masked supplements directly to randomized subjects via mail.

2.3. Subject selection

To enhance the generalizability of the study findings, the DREAM© study aimed to have minimally restrictive inclusion and exclusion criteria to capture a broad spectrum of typical DED patients seeking additional treatment for their symptoms. A complete list of all inclusion and exclusion criteria is shown in Table 1A. The study included patients with moderate to severe DED symptoms, as defined by OSDI [49], and who also demonstrated some repeatable signs of DED on slit lamp examination and by Schirmer test with anesthesia [50]. In addition, participants needed to have dry eye symptoms for at least 6 months and the desire to use artificial tears an average of 2 times per day in the 2 weeks prior to the screening visit.

Table 1A.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for the DRy Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM©) Study.

Inclusion Criteria

|

Exclusion Criteria

|

The eligibility criteria regarding the use of other dry eye treatments during the study are summarized in Table 1B. Participants were allowed to continue to use their current dry eye treatments, such as artificial tears, lid scrubs or Restasis® throughout the study as they would in normal clinical practice. Participants were instructed to continue all of their current dry eye treatments throughout the duration of the study without starting or stopping new treatments. Also, to accommodate those who were currently taking over-the-counter ω3 supplements prior to entry into the study, additional supplementation of up to 1200 mg/day of ω3 was permitted because the total dose would still be within a safe level [31, 32]. Treatment usage was recorded at each study visit so that changes in treatment could be summarized for each treatment group as a secondary outcome measure. Although patients agreed to continue their current medications, discontinuing other treatments when symptoms improved and starting new treatments when symptoms worsened was anticipated.

Table 1B.

Eligibility Criteria Regarding Use of Other Dry Eye Treatments for the DRy Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM©) Study.

|

Subjects with mild DED symptoms (OSDI < 25 at Screening Visit and < 21 at Eligibility Confirmation Visit) were excluded because they might not have DED or would not be able to improve because of OSDI floor effects. In contrast, subjects with severe symptoms (OSDI ≥80) may need very large improvement in order to record a change in their OSDI scores and therefore were also excluded [51].

Other key exclusion criteria included the following: acute allergic conjunctivitis, infection, or inflammation; contact lens wear within the past 30 days; a history of corneal surgery including laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK), ocular surgery within 6 months of the screening visit, use of glaucoma medications, eyelid abnormalities, or ocular surface scarring.

2.4. Randomization procedures

After obtaining written informed consent, participants were examined at a screening visit, and if all entry criteria were met, were given placebo supplements to determine compliance with the protocol during a two-week run-in period, particularly regarding the use of 5 capsules per day. Subjects who returned for an eligibility confirmation visit were enrolled into the study if they demonstrated compliance (< 10% of capsules returned that should have been taken) and still met all inclusion criteria. Study coordinators invoked an online treatment assignment module to generate an assignment of active or placebo supplements that was automatically sent electronically to the Investigational Drug Service. Randomization schedules were stratified by clinical center. All subjects, clinical staff, and laboratory personnel were unaware of the assignment to active or placebo supplements.

2.5. Clinical centers

Investigators at 27 Clinical Centers located throughout the United States participated in the DREAM© study. The practices included a mix of academic medical centers (N = 12) and private practices (N = 15) that were led by board certified ophthalmologists (N = 16) and optometrists (N = 11) who had experience in clinical trials and a special interest in DED (Clinical Centers listed in Appendix under DREAM© Research Group).

To ensure standardization of all study protocols, clinicians, ophthalmic technicians and coordinators at each site were required to complete a certification program before conducting study visits. The program consisted of reading study documents, review of slide sets, successful completion of role-specific knowledge assessments, demonstration of proficiency either during observation or through submission of completed case report forms, and completion of patient-oriented research and good clinical practices training. Training in biomarker sampling, storage, and shipping was accomplished through online training with web-based materials.

2.6. Outcome measures

The primary outcome was a change in dry eye symptoms from baseline (average of the values from the screening and eligibility confirmation visits) to follow-up (average of the values from the visit at 6 and 12 months) as measured by the OSDI score. Averaging of the scores at baseline and in follow-up when little change was expected between 6 and 12 months, decreased the standard deviation of the change in OSDI score, thereby increasing statistical power. A change in symptoms was selected as the primary outcome because patient symptoms are largely responsible for the public health burden and for the care-seeking behavior of dry eye patients and their desire for therapy. Both the Dry Eye WorkShop (DEWS) and the NEI/Industry Workshop on Dry Eyes concluded that the evaluation of subjective symptoms, as measured through a well-designed and validated questionnaire, may be the best way to determine clinical efficacy of treatments and that symptom questionnaires are among the most repeatable of the commonly used diagnostic tests [50, 52, 53].

The OSDI was chosen as the primary outcome because it is the most widely used questionnaire for outcome assessment in clinical trials of DED [20, 54–61], and is one of the few validated questionnaires for DED trials [62, 63]. In addition, a survey study with 241 subjects from 19 sites assessing the OSDI and two other dry eye questionnaires showed that neither of the two other questionnaires had psychometric properties uniformly superior to those of the OSDI [64, 65].

Secondary outcomes included changes in the following clinical signs of DED: 1) tear film break-up time (TBUT); 2) Schirmer test with anesthesia; 3) fluorescein corneal staining using the National Eye Institute [NEI]/industry-recommended guidelines (0–15) [52], and 4) lissamine green conjunctival staining using a modified version of the NEI/industry-recommended guidelines – the entire temporal and the entire nasal section of each eye are graded on a scale of 0 to 3 (0: no staining, 3: severe staining) for a total possible score of 6 in each eye.

Other secondary outcomes included DED symptoms measured by the Brief Ocular Discomfort Inventory (BODI) (a modified version of the Brief Pain Inventory [66]), treatment compliance (measured via blood testing for ω3 levels), ≥10 point decrease in OSDI, use of artificial tears and other DED treatments, DED-related quality of life, cost and cost-effectiveness, and the economic impact of DED (assessed by Short Form-36, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire, and questionnaire on Healthcare Utilization). The incidence of ocular and systemic adverse events was also included as a secondary outcome. All measures of clinical signs were assessed by DREAM©-certified clinicians who followed a standard protocol, including the order of evaluation and testing, with standardized color photos used for grading of vital dye staining, meibum quality and meibomian gland drop out.

Exploratory endpoints were included to determine their usefulness in diagnosing DED, determining severity and/or evaluating improvement in DED (Table 2). These included contrast sensitivity testing, standardized assessment of meibomian gland secretions using the Meibomian Gland Evaluator (TearScience, Morrisville, NC), tear osmolarity as measured by the TearLab Osmometer (TearLab, San Diego, CA), and the presence of matrix metallopeptidase-9 (MMP-9) in tears using InflammaDry® test (Rapid Pathogen Screening Diagnostics, Inc., Sarasota, FL). Noninvasive measures using the OCULUS keratograph (OCULUS, Inc., Arlington, WA) included the following: non-invasive tear breakup time, bulbar redness, tear meniscus height, and meibography. In addition, tear and conjunctival impression cytology samples were collected for analysis by the Ocular Biomarker Research Laboratory at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (New York, NY) in order to measure other biomarkers (listed in Table 2) with a possible relationship to DED. Safety was evaluated by recording the incidence of ocular and systemic adverse events, change in visual acuity, and measurement of intraocular pressure. All serious adverse events were reviewed by a Medical Monitor.

Table 2.

Study Outcomes for the DRy Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM©) Study.

Primary

|

Secondary

|

Exploratory

|

To objectively assess compliance with the treatment regimen and to determine whether effective levels of ω3 were reached, blood samples were collected at the eligibility confirmation(baseline), 6, and 12 month visits to test the systemic levels of fatty acids in erythrocytes (red blood cells). Erythrocytes are the best indicator of fatty acid composition of biological tissue due to a lipid bilayer with a more complete spectrum of phospholipid classes which gives an accurate indication of whether the subjects are compliant with the treatment regimen, and provide an accurate view of the systemic fatty acid levels over the previous 4 months and is not affected by what the participant recently ingested [67, 68].

Blood was also collected to test for autoimmune markers, including the traditional (SS-A/Ro, SS-B/La, antinuclear antibody (ANA), rheumatoid factor (RF)) and novel antibodies (salivary gland protein-1 (SP-1), parotid secretory protein (PSP), carbonic anhydrase VI (CA6)) that are associated with autoimmune diseases such as Sjogren’s Syndrome and included in the Sjo test (IMMCO Diagnostics, Buffalo, NY) [69–71].

2.7. Visit procedures

After randomization, study visits were conducted at 3, 6 and 12 months. Visit procedures were conducted in a specific order to ensure that one measurement would not affect any subsequent measures and to ensure that each eye was examined in a standardized way across all clinicians, sites, and protocol visits (Table 3). The use of artificial tears or any other topical treatment was not permitted for at least 2 h before any study visit. All symptom questionnaires were completed before any other procedures or examination to avoid influencing the participant’s responses.

Table 3.

Study Procedures Order of Testing for the DRy Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM©) Study.

| Primary study | Visit (Month) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | −2wks SV | 00 | 03 | 06 | 09 | 12 |

| Obtain informed consent | X | Y | ||||

| OSDI & BODI questionnaires | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Health economics questionnaires (SF-36, WPAI, Healthcare Use) | X | X | X | |||

| Medical history and events | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Concomitant medication query | X | X | X | X | ||

| Adverse event query | X | X | X | X | ||

| MMP-9 testing | X | X | ||||

| Tear osmolarity | Xb | Xb | Xb | |||

| Keratograph: Break-up time, tear meniscus height, redness and meibomian gland evaluation | Xb | Xb | Xb | |||

| Manifest refraction | X | |||||

| Best corrected VA (if change in VA ≥ 10 letters, do refraction) | X | X | X | X | ||

| Contrast sensitivity | X | X | X | |||

| Tear collection for cytokines | Xb | Xb | Xb | |||

| Slit lamp evaluation (SLE) | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Tear break-up time (TBUT)e | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Corneal fluorescein staininge | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Meibomian gland examinatione | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Lissamine green staininge | X | X | X | X | X | |

| IOP | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Schirmer’s tear test (with anesthetic) | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Urine pregnancy test | Xa | Ya | ||||

| Eligibility determination | X | X | X | |||

| Impression cytology | X | X | X | |||

| Blood collection (Mon-Thurs) for fatty acid determination | X | X | X | |||

| Blood collection (Mon-Thurs) for antibody determination | X | X | ||||

| Collection of unused study supplements | X | X | X | X | ||

| Randomization | X | Y | ||||

| Dispense run-in supplements | X | |||||

| Reminder calls (2 weeks before each visit) | X | X | X | Xc | ||

| “Check-In” telephone call | X | Xd | ||||

| Letter to encourage compliance (sent 1 month after each visit) | X | X | X | Y | ||

SV: Denotes screening visit; 00: Denotes eligibility confirmation visit. Y: Only patients in the Extension Study.

Only women of childbearing potential.

Only at centers with required equipment.

Call should include information about the Extension Study.

Call for final adverse event assessment if not in Extension Study.

Do all 4 procedures OD, then restart for OS.

2.8. Standardization of testing procedures

All testing was conducted following a standardized protocol. Standardized supplies were used at all sites, including vital dyes (2% fluorescein and 1% lissamine green) made by a central compounding pharmacy - Leiter’s (San Jose, CA), Compounded Solutions in Pharmacy (Monroe, CT), and the University of Pennsylvania Investigational Drug Service (Philadelphia, PA). Preset micropipettes (5 μl) were used to administer the dyes, and cobalt yellow filter was used to during the slit-lamp examination to assess fluorescein corneal staining. TearLab osmolarity machines were calibrated daily to ensure accurate measurements and Meibomian Gland Evaluators were provided to each center to ensure standardized lid pressure was used when evaluating meibum secretions. Standardized hard copy photos of grading scale reference images were used by each site for grading ocular surface staining, for the evaluation of meibum, and for assessing meibomian gland dropout from meibography images.

2.9. Sample size and statistical analysis

Sample size was estimated for comparing the two treatment groups on the mean change in OSDI score, as defined above, with a two-sample t-test and an alpha level of 0.05. Assuming a standard deviation for change in OSDI score of 18 points and missing data for 15% of patients, we determined that a sample of 505 patients would provide statistical power of 90% to detect a 6-point mean difference between treatment groups. Although the minimal clinically meaningful difference in OSDI scores for individuals is 10, a difference in means between active and placebo groups was set at 6, representing a small to moderate effect size 0.33. The study protocol specified that each secondary outcome measure would be tested at the 0.05 level. All patients are analyzed in the treatment group to which they were assigned, regardless of compliance.

Four sets of subgroups, as defined below, were pre-specified to assess variation in treatment effect. Variation in subgroups is assessed by including and testing interaction terms in a regression model of change in ODSI score.

Severity of symptoms as measured by the baseline OSDI score Severe symptoms are considered as an OSDI score (average of Screening and Baseline Visit scores) ≥40

- Severity of signs based on the 4 signs used for eligibility determination. Severe signs are considered present if one or both eyes of a patient had scores (average from the Screening and Baseline Visits) meeting each of the 4 criteria below:

- Conjunctival staining ≥2

- Corneal staining ≥4

- TBUT < 5 s

- Schirmer ≤7 mm/5 min

High DHA/EPA level. Participants with both their DHA level and EPA level above the mean value from the Kennedy Krieger Institute adult control group [N = 147; mean age = 49.5 +/− 17.0] (DHA: 3.7%, EPA: 0.6%)

Inflammation status as measured by the percent of HLA-DR positive epithelial cells from impression cytology at baseline. High inflammation status is considered as a percentage of HLA-DR positive cells greater than the median from the DREAM© study population.

3. Results

Between November 2014 and July 2016, 535 subjects were enrolled in the DREAM© study. The baseline characteristics for the entire cohort are summarized in Table 4, with the average and standard deviation for each characteristic.

Table 4.

Baseline Characteristics of all participants in the DRy Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM©) study.

| Characteristic | Overall 535 patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58.0 | ± 13.2 |

| Gender - no. (%) | ||

| Female | 434 | (81.1) |

| Male | 101 | (18.9) |

| Race - no. (%) | ||

| White | 398 | (74.4) |

| Black | 64 | (12.0) |

| Other | 73 | (13.6) |

| Ethnicity - no. (%) | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 68 | (12.7) |

| Other | 467 | (87.3) |

| OSDI score, mean | ||

| Total | 44.4 | ± 14.2 |

| Vision-related function subscale | 37.8 | ± 17.7 |

| Ocular symptoms | 46.6 | ± 17.1 |

| Environmental triggers subscale | 55.6 | ± 24.5 |

| Short Form-36 score, mean | ||

| Physical health | 47.5 | ± 9.7 |

| Mental health | 52.3 | ± 9.4 |

| Brief Ocular Discomfort Index scorea, mean | ||

| Discomfort subscale | 44.2 | ± 16.6 |

| Pain interference subscale | 27.0 | ± 17.6 |

| Use of dry eye treatments, no. (%) | ||

| Artificial tears, drops or gel | 424 | (79.3) |

| Cyclosporine drops | 205 | (38.3) |

| Warm lid soaks | 114 | (21.3) |

| Lid scrubs or baby shampoo | 83 | (15.5) |

| Any other treatment | 268 | (50.1) |

| Systemic diseaseb | ||

| Sjogren syndrome | 56 | (10.5) |

| Thyroid disease | 108 | (20.2) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 49 | (9.2) |

| None of the above | 357 | (66.7) |

| Fatty acid in red blood cells, %, meanc | ||

| Eicosapentaenoic | 0.6 | ± 0.4 |

| Docosahexaenoic | 3.9 | ± 1.1 |

| Omega-3 index(EPA + DHA) | 4.5 | ± 1.5 |

| Oleic acid (omega-9) | 11.1 | ± 1.2 |

| ω6 to ω3 ratio, meanc | 4.8 | ± 1.4 |

| 1022 Eyes | ||

| Conjunctival staining scorea, mean | 3.0 | ± 1.4 |

| Corneal staining scorea, mean | 3.9 | ± 2.7 |

| Tear break-up timea, sees, mean | 3.1 | ± 1.5 |

| Schirmer testa, mm, mean | 9.6 | ± 6.5 |

Plus-minus values are means ± SD.

Average of values from screening and eligibility confirmation visits.

Ongoing or past history by patient report; may have > 1 disease.

Missing values for 15 subjects.

4. Discussion

This trial design methodology paper demonstrates an approach to a real-world clinical trial for both dry eye disease (DED) and nutritional supplements. The design of the DREAM© Study is unique in that it is designed so that results will be applicable to typical patients seen in clinical practice. This is in contrast to a typical FDA trial seeking approval for a new treatment: strict inclusion and exclusion criteria are used which do not correlate with typical clinical practice. Nearly all past RCT’s for treatments of DED have had very restrictive inclusion and exclusion criteria that would have excluded many of the DREAM© participants, and have required that other treatments or artificial tears be suspended before and during the trial. Subjects in the DREAM© study had symptoms of DED despite current treatment, but were allowed to continue current therapies, such as artificial tears, as would be done in clinical practice. In addition, characteristics of DREAM© may also be helpful for other trials studying nutritional supplements to provide high quality, generalizable information. This paper highlights the clinical trial elements that make DREAM© a real-world trial, and provides information to those interested in conducting RCT’s on DED or nutritional supplements.

The DREAM© study is the first large-scale, real-world, double-masked, randomized clinical trial (RCT) that studies the long-term efficacy and safety of omega-3 (ω3) supplementation for symptomatic DED. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are designed to enroll a population of DED patients that mirrors typical symptomatic DED patients who request further treatment from eye care providers despite current dry eye treatment. The DREAM© study has the largest sample size and study duration, and utilized the highest safe dose of ω3 fish oil-derived supplements as compared to other DED trials. In addition, the length of DREAM© (1 year) diminished seasonality as a possible factor impacting a subject’s DED severity, and also provided valuable longitudinal data on DED.

Selecting an appropriate placebo is key to any quality RCT. After an extensive review of past ω3 RCT’s and consultation with a review counsel and experts in the field of nutritional supplements, refined olive oil was selected as the placebo for DREAM©. Olive oil has been used as a placebo in almost all other ω3 RCTs [16, 18, 36, 40–44], since it was not expected to have an effect on inflammation or DED. Refined olive oil is very low in polyphenols which are considered the primary source of the beneficial health effects seen from olive oil [45, 46]. In addition, the daily dose of olive oil in DREAM© was only 5 g per day, or about 1 teaspoon. Studies testing the benefits of olive oil, usually as part of the Mediterranean Diet, have supplied daily doses of at least 60 g [47], and sometimes as high as 100 g [48], over 20 times higher than the DREAM© placebo. Furthermore, the DREAM© olive oil was 68% oleic acid, an omega-9 fatty acid considered neutral with respect to inflammation. In addition, testing fatty acid content of erythrocytes provided an objective measure of systemic levels of multiple fatty acids, including EPH, DHA, and oleic acid.

The DREAM© real-world clinical trial design offers a new approach for trials on DED treatments. The DREAM© trial design differs from typical RCTs on new treatments for DED by including participants who continue to be symptomatic despite current treatment, and allowing them to continue their current treatment throughout the study. This approach should allow for greater usefulness in clinical practice where patients are not restricted in which therapies they are allowed to continue when beginning a new treatment. DREAM© was also designed to enroll real world patients seen in optometry and ophthalmology, academic and private practices throughout the USA, which in turn increased the generalizability of its results. Utilizing a study length of one year was expected to decrease the effect of external factors, such as climate and seasonal changes on the signs and symptoms of DED. In addition, the highest safe dose and most bioavailable formulation of ω3 was used, and compliance was assessed both by pill count and erythrocyte analysis to provide objective verification of systemic levels reached. The placebo was olive oil, which is a commonly used placebo in RCT’s studying ω3 supplementation for DED and other diseases [16, 18, 36, 40–44]. Significant efforts to mask active and placebo supplements were incorporated. Finally, clinical examinations were standardized including teaching of all trial personnel, verification of study-specific training, utilization of standardized supplies and well described exam procedures including grading scales.

The DREAM© study is also strengthened by its exploratory outcomes, such as the collection of biomarkers, tear osmolarity, percent HLA-DR positive cells and tear cytokines. The DREAM© study’s exploratory outcomes go beyond what is normally tested in FDA trials for new DED treatments, and may provide objective metrics that could aid in classifying disease severity and be useful for determining treatment response and outcome measures for clinical trials. Biomarkers may also contribute to our understanding of the pathology that occurs on the ocular surface with DED and offer potentially new targets for treatment. These results will be useful to other clinicians and researchers interested in DED and ocular surface pathology as they continue investigations into disease mechanisms and design future clinical trials for new treatments.

In addition to setting the standard on how a dry eye trial should be designed, DREAM© is also an ideal role model on how to design a nutritional trial. The placebo treatment mimics the common diet and is expected to be neutral with respect to the disease being studied. All components of the active and placebo treatment (i.e. other fatty acids) were analyzed and defined by both the manufacturer and an independent lab and deemed that they will not have any interference with the active supplement or have an effect on the disease being studied. Erythrocytes were chosen to measure systemic levels of the supplements being given to patients since erythrocytes provide an accurate picture of the levels over the previous 4 months, whereas plasma can fluctuate extensively based on what is recently ingested [67, 68].

To date, there have been 8 large (> 100 participants) RCT’s evaluating ω3 supplementation for DED [16, 17, 19, 40, 41, 72–74]. However, some of these RCTs had significant differences from the DREAM© study design. For example, Brignole-Baudouin et al. 2011 and Wang et al. 2016 used a combination of ω3 and omega-6 (ω6), while the DREAM© study supplements only contained ω3 fatty acids. DREAM© study participants could not wear contact lenses during the study, but Bhargava et al. 2015 and Wang et al. 2016 required contact lens for eligibility. Finally, Bhargava et al. 2013 did not list baseline values for several of their outcomes and therefore preclude comparisons with the present study. In addition, the studies led by Bhargava et al. were held in India where participants likely have a very different diet compared to the USA participants, as well as differences in ethnicities. We compared the baseline characteristics of the DREAM© study to the remaining large RCT’s in which baseline data were reported and those for which DREAM© subjects may have been eligible (Table 5); DREAM© participants had more severity as measured by OSDI scores and ocular surface findings.

Table 5.

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics of Omega-3 Studies for the Treatment of Dry Eye Disease.

| DREAM© | Epitropoulos 2016 [17] | Bhargava 2015 [73] | Bhargava 2016 [40] (Current Eye Research) | Bhargava 2016 [41] (Eye & Contact Lens) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily omega-3 dose (mg) | 3000 | 2240 | 600 | 1200 | 2400 |

| Sample size | 535 | 105 | 456 | 130 | 522 |

| Duration of study | 12 months | 3 months | 3 months | 6 months | 45 days |

| Age, yrs. (mean) | 58.0 ± 13.2 | 56.8 ± 17.0 | 23.3 ± 5.2 | 48.3 ± 4.2 | 29.3 ± 4.9 |

| OSDI Symptom Score (mean) | 44.4 ± 14.2 | 29.8 ± 21.1 | 7.7 ± 2.3a | 8.9 ± 2.5a | 7.9 ± 2.3a |

| Corneal staining (mean) | 3.9 ± 2.7b | 1.4 ± 1.1c | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Conjunctival staining (mean) | 3.0 ± 1.4d | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Tear film breakup time, sec (mean) | 3.1 ± 1.5 | 4.7 ± 2.6 | 11.6 ± 1.8 | 9.4 ± 2.0 | 8.8 ± 2.0 |

| Schirmer test, mm/5 min (mean) | 9.6 ± 6.5 | 11.2 ± 7.5 | 20.0 ± 4.5 | 13.4 ± 5.1 | 15.8 ± 6.3 |

Symptoms assessed by the dry eye questionnaire and scoring system (DESS) 0 to 18 (0: no symptoms, 18: severe symptoms).

National Eye Institute [NEI]/industry-recommended guidelines (0: no staining, 15: severe staining).

Oxford staining scale 0 to 5 (0: no staining, 5: severe staining).

Modified NEI/industry-recommended scale (0: no staining, 6: severe staining).

The DREAM© study population’s baseline systemic levels of ω3 and oleic acid (Table 4) mirror the values reported for the US population [75]. Harris et al. [75] defined fatty acid norms in the general population by measuring systemic fatty acid levels in nearly 160,000 people. The baseline ω3 index (EPA + DHA) of the DREAM© study population approximately corresponds to the 50th percentile found by Harris et al. [75] In addition, personal communication with Kennedy Krieger Institute indicate that their mean systemic oleic acid clinical laboratory control values are nearly identical to the mean DREAM© baseline systemic oleic acid levels (Kennedy Krieger Institute = 11.3%; DREAM© = 11.1%).

In summary, the DREAM© study was a carefully designed RCT that will provide generalizable information on the use of ω3 that can be applied to clinical practice. DREAM© will also fill an acknowledged gap in understanding DED by collecting longitudinal data on a well-characterized dry eye population. Exploratory endpoints may provide guidelines for future research to improve our understanding of DED and possibly point to new targets for treatment.

Acknowledgements and disclosures

(a). Supported by cooperative agreements U10EY022879 and U10EY022881 from the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, and Office of Dietary Supplements.

(b). Financial Disclosures: Penny A. Asbell: Receives research funding from MC2 Therapeutics and Novartis; is a consultant for Novartis, ScientiaCME, Shire, and WebMD; has received travel/financial compensation from Novartis, Santen, ScientiaCME, and Shire.

Maureen Maguire: No financial disclosures.

Ellen Peskin: No financial disclosures.

Vatinee Bunya: receives research funding from Bausch & Lomb Eric Kuklinski: receives research funding from MC2 Therapeutics

(c). Other Acknowledgements:

Access Business Group, LLC (Ada, MI).

Appendix A. The Dry Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM©) Study Research Group

Certified Roles at Clinical Centers: Clinician (CL); Clinic Coordinator (CC), Data Entry Staff (DE) Principal Investigator (PI), Technician (T).

Milton M. Hom (Azusa, CA): Milton M. Hom, OD FAAO (PI); Melissa Quintana (CC/T); Angela Zermeno (CC/T).

Pendleton Eye Center (Oceanside, CA): Robert Pendleton, MD, PhD. (PI); Debra McCluskey (CC); Diana Amador (T); Ivette Corona (CC/T); Victor Wechter, MD (CL).

University of California School of Optometry, Berkeley (Berkeley, CA): Meng C. Lin, OD PhD FAAO (PI); Carly Childs (CC); Uyen Do (CC); Mariel Lerma (CC); Wing Li, OD (T); Zakia Young (CC); Tiffany Yuen, OD (CC/T).

Clayton Eye Center (Morrow, GA): Harvey Dubiner, MD (PI); Heather Ambrosia, OD (C); Mary Bowser (CC/T); Peter Chen, OD (CL); Helen Dubiner, PharmD, CCRC (CC/T); Cory Fuller (CC/T); Kristen New (DE); Tu Vy Nguyen (C); Ethen Seville (CC/T); Daniel Strait, OD (CL); Christopher Wang (CC/T); Stephen Williams (CC/T); Ron Weber, MD (CL).

University of Kansas (Prairie Village, KS) John Sutphin, MD (PI); Miranda Bishara, MD (CL); Anna Bryan (CC); Asher Ertel (CC/T); Kristie Green (T); Gloria Pantoja, Ashley Small (CC); Casey Williamson (T).

Clinical Eye Research of Boston (Boston, MA): Jack Greiner, MS OD DO, PhD (PI); EveMarie DiPronio (CC/T); Michael Lindsay (CC/T); Andrew McPherson (CC/T); Paula Oliver (CC/T); Rina Wu (T).

Mass Eye & Ear Infirmary (Boston, MA): Reza Dana, MD (PI); Tulio Abud (T): Lauren Adams (T); Marissa Arnofsky (T); Jillian Candlish, COA (T); Pranita Chilakamarri (DE); Joseph Ciolino, MD (CL); Naomi Crandall (T); Antonio DiZazzo (T); Merle Fernandes (T); Mansab Jafri (T); Britta Johnson (T); Ahmed Kheirkhah (T); Sally Kiebdaj (CC/T); Andrew Mullins (CC/T); Milka Nova (T); Vannarut Satitpitakul (T); Chunyi Shao (T); Kunal Suri (T); Vijeeta Tadla (CC); Saboo Ujwala (T); Jia Yin MD, PhD (T); Man Yu (T).

Kellogg Eye Center, University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI): Roni Shtein, MD (PI); Christopher Hood, MD (CL); Munira Hussain, MS, COA, CCRP (CC/T); Erin Manno, COT (T); Laura Rozek, COT (T/DE).

Minnesota Eye Consultants (Bloomington, MN): David R. Hardten, MD FACS (PI); Kimberly Baker (T); Alex Belsaas (T); Erich Berg (CC/T); Alyson Blakstad, OD (CL); Ken DauSchmidt (T); Lindsey Fallenstein (CC/T); Ahmad M. Fahmy OD (CL); Mona M. Fahmy OD FAAO (CL); Ginny Georges (T); Deanna E. Harter (CL); Scott G. Hauswirth, OD (CL); Madalyn Johnson (T); Ella Meshalkin (T); Rylee Pelzer (CC/T); Joshua Tisdale (CC/T); JulieAnn C. Wick (CL).

Tauber Eye Center (Kansas City, MO): Joseph Tauber, MD, PHD (PI); Megan Hefter (CC/T).

Silverstein Eye Centers (Kansas City, MO): Steven Silverstein, MD (PI); Cindy Bentley (CC/T); Eddie Dominguez (CC/T); Kelsey Kleinsasser, OD (CL).

Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai, (New York, NY): Penny Asbell, MD, FACS, MBA (PI); Brendan Barry (CC/T); Eric Kuklinski (CC/T); Afsana Amir (CC/T); Neil Chen (CC/T); Marko Oydanich (CC/T); Viola Spahiu (CC/T); An Vo, MD (T); Matthew Weinstein, DO (T).

University of Rochester Flaum Eye Institute (Rochester, NY): Tara Vaz, OD (PI); Holly Hindman, MD (PI); Rachel Aleese (CC/T); Andrea Czubinski (CC/T); Gary Gagarinas, COMT CCRA (CC/T); Peter McDowell (CC); George O’Gara (DE); Kari Steinmetz (CC/T).

University of Pennsylvania Scheie Eye Institute (Philadelphia, PA): Vatinee Bunya, MD (PI); Michael Bezzerides (CC/T); Dominique Caggiano (CC/T); Sheri Drossner (T); Joan Dupont (CC); Marybeth Keiser (CC/T); Mina Massaro, MD (CL); Stephen Orlin, MD (CL); Ryan O’Sullivan (CC/T).

Southern College of Optometry (Memphis, TN): Michael Christensen, OD PhD (PI); Havilah Adkins (CC); Randy Brafford (CC/T); Cheryl Ervin (CL); Rachel Grant OD (CL); Christina Newman (CL).

Shettle Eye Research (Largo, FL): Lee Shettle, DO (PI); Debbie Shettle (CC).

Stephen Cohen, OD, PC (Scottsdale, AZ): Stephen Cohen, OD (PI); Diane Rodman (CC/T).

Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland, OH): Loretta Szczotka-Flynn, OD PhD (PI); Tracy Caster (T); Pankaj Gupta MD MS (CL); Sangeetha Raghupathy (CC/T); Rony Sayegh, MD (CL). Mayo Clinic Arizona (Scottsdale, AZ): Joanne Shen, MD (PI); Nora Drutz, CCRC (CC); Lauren Joyner, COA (T); Mary Mathis, COA (T); Michaele Menghini, CCRP (CC); Charlene Robinson, CCRP (CC).

Wolston & Goldberg Eye Associates (Torrance, CA): Damien Goldberg, MD (PI); Lydia Jenkins (T); Brittney Rodriguez (CC/T); Jennifer Picone Jones (CC/T); Nicole Thompson (T), Barry Wolstan, MD (CL).

Northeast Ohio Eye Surgeons (Stow, OH): Marc Jones, MD (PI); April Lemaster (CC/T); Julie Ransom-Chaney (T); William Rudy, OD (CL).

Tufts Medical Center (Boston, MA): Pedram Hamrah, MD (PI); Mildred Commodore (CC); Christian Iyore (T); Lioubov Lazarev (T): Leah Mullen (T); Nicholas Pondelis (T); Carly Satsuma (CC).

University of Illinois at Chicago (Chicago, IL): Sandeep Jain, MD (PI); Peter Cowen (CC/T); Joelle Hallak (CC);Christine Mun (CC/T); Roxana Toh (CC).

The Eye Centers of Racine & Kenosha (Racine, WI): Inder Singh, MD (PI); Pamela Lightfield (CC/T); Eunice Lowery (T); Sarita Ornelas (T); R. Krishna Sanka, MD (CL); Beth Saunders (T).

Mulqueeny Eye Centers (St. Louis, MO): Sean P. Mulqueeny, OD (PI); Maggie Pohlmeier (CC/T).

Oculus Research at Garner Eyecare Center (Raleigh, NC): Carol Aune, OD (PI); Hoda Gabriel (CC); Kim Major Walker, RN MS (CC/T); Jennifer Newsome (CC/T).

Resource centers

Chairman’s Office (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY): Penny Asbell, MD, FACS, MBA (Study Chair); Brendan Barry (Clinical Research Coordinator); Eric Kuklinski (Clinical Research Coordinator); Michael Farkouh, MD FRCPC, FACC, FAHA (Medical Safety Monitor); Seunghee Kim-Schulze, PhD (Consultant); Robert Chapkin, PhD, MSc. (Consultant); Giampaolo Greco, PhD (Consultant); Artemis Simopoulos, MD (Consultant); Ines Lashley (Administrative Assistant); Peter Dentone, MD (Clinical Research Coordinator); Neha Gadaria-Rathod, MD (Clinical Research Coordinator); Morgan Massingale, MS (Clinical Research Coordinator); Nataliya Antonova (Clinical Research Coordinator).

Coordinating Center (University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA): Maureen G. Maguire, PhD (PI); Mary Brightwell-Arnold, SCP (Systems Analyst) John Farrar, MD PhD (Consultant); Sandra Harkins (Staff Assistant); Jiayan Huang, MS (Biostatistician); Kathy McWilliams, CCRP (Protocol Monitor); Ellen Peskin, MA, CCRP (Director); Maxwell Pistilli, MS, MEd (Biostatistician); Susan Ryan (Financial Administrator); Hilary Smolen (Research Fellow); Claressa Whearry (Administrative Coordinator); Gui-Shuang Ying, PhD (Senior Biostatistician) Yinxi Yu (Biostatistician).

Biomarker Laboratory (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY): Yi Wei, PhD, DVM (co-Director, Biomarker Laboratory); Neeta Roy, PhD (co-Director, Biomarker Laboratory); Seth Epstein, MD (Former co-Director; Biomarker Laboratory); Penny A. Asbell, MD, FACS, MBA (Director and Study Chair).

Investigational Drug Service (University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA): Kenneth Rockwell, Jr., PharmD MS (Director).

Peroxisomal Diseases Laboratory at the Kennedy Krieger Institute, Johns Hopkins University Baltimore MD: Ann Moser (Co-Director/Consultant); Richard O. Jones, PhD (Co-Director/Consultant).

Meibomian Gland Reading Center (University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA): Ebenezer Daniel, MBBS, MPH, PhD, (PI); E. Revell Martin (Image Grader); Candace Parker Ostroff, (Image Grader); Eli Smith (Image Grader); Pooja Axay Kadakia (Student Researcher).

National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services: Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH (Program Officer).

Office of Dietary Supplements/National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services.

Committees

Executive Committee (Members from all terms of appointment): Penny Asbell, MD FACS, MBA (Chair); Brendan Barry, MS; Munira Hussain, MS, COA, CCRP; Jack Greiner, MS OD PhD; Milton Hom, OD, FAAO; Holly Hindman, MD, MPH; Eric Kuklinski, BA; Meng C. Lin OD, PhD. FAAO; Maureen G. Maguire, PhD; Kathy McWilliams, CCRP; Ellen Peskin, MA, CCRP; Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH; Roni Shtein, MD, MS; Steven Silverstein, MD; John Sutphin, MD.

Operations Committee: Penny Asbell, MD FACS, MBA (Chair); Brendan Barry, MS; Eric Kuklinski, BA; Maureen G. Maguire, PhD; Kathleen McWilliams, CCRP, Ellen Peskin, MA, CCRP; Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH.

Clinic Monitoring Committee: Ellen Peskin, MA, CCRP (Chair); Mary Brightwell-Arnold, SCP, Maureen G. Maguire, PhD; Kathleen McWilliams, CCRP.

Data and Safety Monitoring Committee: Stephen Wisniewski, PhD (Chair); Tom Brenna, PhD; William G. Christen Jr., SCD, OD, PhD; Jin-Feng Huang, PhD; Cynthia S. McCarthy, DHCE, MA; Susan T. Mayne, PhD; Mari Palta, PhD; Oliver D. Schein, MD, MPH, MBA.

Industry Contributors of Products and Services

Access Business Group, LLC (Ada, MI) Jennifer Chuang, PhD. CCRP; Maydee Marchan, M.Ch.E; Tian Hao, PhD; Christine Heisler; Charles Hu, PhD; Clint Throop, Vikas Moolchandani, PhD. Compounded Solutions in Pharmacy (Monroe, CT).

Leiter’s (San Jose, CA).

Immco Diagnostics Inc. (Buffalo NY).

OCULUS Inc. (Arlington, WA).

RPS Diagnostics, Inc. (Sarasota, FL).

TearLab Corporation (San Diego, CA).

TearScience Inc. (Morrisville, NC).

References

- [1].Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, Caffery B, Dua HS, Joo CK, Liu Z, Nelson JD, Nichols JJ, Tsubota K, Stapleton F, TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report, Ocul. Surf 15 (2017) 276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Belmonte C, Nichols JJ, Cox SM, Brock JA, Begley CG, Bereiter DA, Dartt DA, Galor A, Hamrah P, Ivanusic JJ, Jacobs DS, McNamara NA, Rosenblatt MI, Stapleton F, Wolffsohn JS, TFOS DEWS II pain and sensation report, Ocul. Surf 15 (2017) 404–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Farrand KF, Fridman M, Stillman IO, Schaumberg DA, Prevalence of diagnosed dry eye disease in the United States among adults aged 18 years and older, Am J. Ophthalmol 182 (2017) 90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Stapleton F, Garrett Q, Chan C, Craig J, The epidemiology of dry eye disease, Essentials Ophthalmol. (2015) 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Moss SE, Klein R, Klein BE, Prevalence of and risk factors for dry eye syndrome, Arch. Ophthalmol 118 (2000) 1264–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yu J, Asche CV, Fairchild CJ, The economic burden of dry eye disease in the United States: a decision tree analysis, Cornea 30 (2011) 379–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wei Y, Asbell PA, The core mechanism of dry eye disease is inflammation, Eye Cont. Lens 40 (2014) 248–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bron AJ, de Paiva CS, Chauhan SK, Bonini S, Gabison EE, Jain S, Knop E, Markoulli M, Ogawa Y, Perez V, Uchino Y, Yokoi N, Zoukhri D, Sullivan DA, TFOS DEWS II pathophysiology report, Ocul. Surf 15 (2017) 438–510.28736340 [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jones L, Downie LE, Korb D, Benitez-Del-Castillo JM, Dana R, Deng SX, Dong PN, Geerling G, Hida RY, Liu Y, Seo KY, Tauber J, Wakamatsu TH, Xu J, Wolffsohn JS, Craig JP, TFOS DEWS II management and therapy report, Ocul. Surf 15 (2017) 575–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mozaffarian D, Wu JH, omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: effects on risk factors, molecular pathways, and clinical events, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 58 (2011) 2047–2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Goldberg RJ, Katz J, A meta-analysis of the analgesic effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for inflammatory joint pain, Pain 129 (2007) 210–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Simopoulos AP, omega-3 fatty acids in inflammation and autoimmune diseases, J. Am. Coll. Nutr 21 (2002) 495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gioxari A, Kaliora AC, Marantidou F, Panagiotakos DP, Intake of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Nutrition 45 (2017) 114–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Barrett SJ, The role of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in cardiovascular health, Altern. Ther. Health Med 19 (Suppl. 1) (2013) 26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lee SM, An WS, Cardioprotective effects of omega −3 PUFAs in chronic kidney disease, Biomed. Res. Int. (2013) (2013) 712949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bhargava R, Kumar P, Kumar M, Mehra N, Mishra A, A randomized controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids in dry eye syndrome, Int. J. Ophthalmol 6 (2013) 811–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Epitropoulos AT, Donnenfeld ED, Shah ZA, Holland EJ, Gross M, Faulkner WJ, Matossian C, Lane SS, Toyos M, Bucci FA Jr., Perry HD, Effect of oral re-esterified omega-3 nutritional supplementation on dry eyes, Cornea 35 (2016) 1185–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Macsai MS, The role of omega-3 dietary supplementation in blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction (an AOS thesis), Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc 106 (2008) 336–356. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Brignole-Baudouin F, Baudouin C, Aragona P, Rolando M, Labetoulle M, Pisella PJ, Barabino S, Siou-Mermet R, Creuzot-Garcher C, A multicentre, double-masked, randomized, controlled trial assessing the effect of oral supplementation of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids on a conjunctival inflammatory marker in dry eye patients, Acta Ophthalmol. 89 (2011) e591–e597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wojtowicz JC, Butovich I, Uchiyama E, Aronowicz J, Agee S, McCulley JP, Pilot, prospective, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial of an omega-3 supplement for dry eye, Cornea 30 (2011) 308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Singh M, Stark PC, Palmer CA, Gilbard JP, Papas AS, Effect of omega-3 and vitamin E supplementation on dry mouth in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome, Spec. Care Dentist 30 (2010) 225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gheita T, Kamel S, Helmy N, El-Laithy N, Monir A, omega-3 fatty acids in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: effect on cytokines (IL-1 and TNF-alpha), disease activity and response criteria, Clin. Rheumatol 31 (2011) 363–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Caughey GE, James MJ, Proudman SM, Cleland LG, Fish oil supplementation increases the cyclooxygenase inhibitory activity of paracetamol in rheumatoid arthritis patients, Complement. Ther. Med 18 (2010) 171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bahadori B, Uitz E, Thonhofer R, Trummer M, Pestemer-Lach I, McCarty M, Krejs GJ, omega-3 fatty acids infusions as adjuvant therapy in rheumatoid arthritis, JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr 34 (2010) 151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Berbert AA, Kondo CR, Almendra CL, Matsuo T, Dichi I, Supplementation of fish oil and olive oil in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, Nutrition 21 (2005) 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bjorkkjaer T, Brunborg LA, Arslan G, Lind RA, Brun JG, Valen M, Klementsen B, Berstad A, Froyland L, Reduced joint pain after short-term duodenal administration of seal oil in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: comparison with soy oil, Scand. J. Gastroenterol 39 (2004) 1088–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Trebble TM, Stroud MA, Wootton SA, Calder PC, Fine DR, Mullee MA, Moniz C, Arden NK, High-dose fish oil and antioxidants in Crohn’s disease and the response of bone turnover: a randomised controlled trial, Br. J. Nutr 94 (2005) 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Almallah YZ, Ewen SW, El-Tahir A, Mowat NA, Brunt PW, Sinclair TS, Heys SD, Eremin O, Distal proctocolitis and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs): the mucosal effect in situ, J. Clin. Immunol 20 (2000) 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Varghese TJ, Coomansingh D, Richardson S, Mowat NA, Brunt PW, ElTahir A, Eremin O, Clinical effect on ulcerative colitis with dietary supplementation by omega-3 fatty acids; A double blind, randomised study, Gastroenterology 118 (2000) (A588–A588). [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nodari S, Triggiani M, Campia U, Manerba A, Milesi G, Cesana BM, Gheorghiade M, Dei Cas L, N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the prevention of atrial fibrillation recurrences after electrical cardioversion: a prospective, randomized study, Circulation 124 (2011) 1100–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Harris WS, Expert opinion: omega-3 fatty acids and bleeding-cause for concern? Am. J. Cardiol 99 (2007) 44C–46C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].N.a.A. EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Scientific opinion on the tolerable upper intake level of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), EFSA J. (2012) 48. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Simopoulos AP, The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids, Biomed Pharmacother 56 (2002) 365–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Simopoulos AP, omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids: biological effects, World Rev. Nutr. Diet 99 (2009) 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kawakita T, Kawabata F, Tsuji T, Kawashima M, Shimmura S, Tsubota K, Effects of dietary supplementation with fish oil on dry eye syndrome subjects: randomized controlled trial, Biomed. Res 34 (2013) 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Deinema LA, Vingrys AJ, Wong CY, Jackson DC, Chinnery HR, Downie LE, A randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial of two forms of omega-3 supplements for treating dry eye disease, Ophthalmology 124 (2017) 43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Neubronner J, Schuchardt JP, Kressel G, Merkel M, von Schacky C, Hahn A, Enhanced increase of omega-3 index in response to long-term n-3 fatty acid supplementation from triacylglycerides versus ethyl esters, Eur. J. Clin. Nutr 65 (2011) 247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Rosenberg ES, Asbell PA, Essential fatty acids in the treatment of dry eye, Ocul. Surf 8 (2010) 18–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Dyerberg J, Madsen P, Moller JM, Aardestrup I, Schmidt EB, Bioavailability of marine n-3 fatty acid formulations, Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 83 (2010) 137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bhargava R, Chandra M, Bansal U, Singh D, Ranjan S, Sharma S, A randomized controlled trial of omega 3 fatty acids in Rosacea patients with dry eye symptoms, Curr. Eye Res 41 (2016) 1274–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bhargava R, Kumar P, Arora Y, Short-term omega 3 fatty acids treatment for dry eye in young and middle-aged visual display terminal users, Eye Cont. Lens 42 (2016) 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rauch B, Schiele R, Schneider S, Diller F, Victor N, Gohlke H, Gottwik M, Steinbeck G, Del Castillo U, Sack R, Worth H, Katus H, Spitzer W, Sabin G, Senges J, Group OS, omega, a randomized, placebo-controlled trial to test the effect of highly purified omega-3 fatty acids on top of modern guideline-adjusted therapy after myocardial infarction, Circulation 122 (2010) 2152–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Investigators OT, Bosch J, Gerstein HC, Dagenais GR, Diaz R, Dyal L, Jung H, Maggiono AP, Probstfield J, Ramachandran A, Riddle MC, Ryden LE, Yusuf S, N-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with dysglycemia, N. Engl. J. Med 367 (2012) 309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Cleland LG, French JK, Betts WH, Murphy GA, Elliott MJ, Clinical and bio-chemical effects of dietary fish oil supplements in rheumatoid arthritis, J. Rheumatol 15 (1988) 1471–1475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Pandey KB, Rizvi SI, Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease, Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev 2 (2009) 270–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Gorzynik-Debicka M, Przychodzen P, Cappello F, Kuban-Jankowska A, Marino Gammazza A, Knap N, Wozniak M, Gorska-Ponikowska M, Potential health benefits of olive oil and plant polyphenols, Int. J. Mol. Sci 19 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J, Covas MI, Corella D, Aros F, Gomez-Gracia E, Ruiz-Gutierrez V, Fiol M, Lapetra J, Lamuela-Raventos RM, Serra-Majem L, Pinto X, Basora J, Munoz MA, Sorli JV, Martinez JA, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Investigators PS, Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet, N. Engl. J. Med 368 (2013) 1279–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Pagnan A, Corrocher R, Ambrosio GB, Ferrari S, Guarini P, Piccolo D, Opportuno A, Bassi A, Olivieri O, Baggio G, Effects of an olive-oil-rich diet on erythrocyte membrane lipid composition and cation transport systems, Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 76 (1989) 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, Hirsch JD, Reis BL, Reliability and validity of the ocular surface disease index, Arch. Ophthalmol 118 (2000) 615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, Djalilian A, Dogru M, Dumbleton K, Gupta PK, Karpecki P, Lazreg S, Pult H, Sullivan BD, Tomlinson A, Tong L, Villani E, Yoon KC, Jones L, Craig JP, TFOS DEWS II diagnostic methodology report, Ocul. Surf 15 (2017) 539–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Miller KL, Walt JG, Mink DR, Satram-Hoang S, Wilson SE, Perry HD, Asbell PA, Pflugfelder SC, Minimal clinically important difference for the ocular surface disease index, Arch. Ophthalmol 128 (2010) 94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Lemp MA, Report of the National eye Institute/industry workshop on clinical trials in dry eyes, CLAO J. 21 (1995) 221–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].DEWS, Methodologies to diagnose and monitor dry eye disease: report of the diagnostic methodology Subcommittee of the International dry eye WorkShop (2007), Ocul. Surf 5 (2007) 108–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Sall K, Stevenson OD, Mundorf TK, Reis BL, Two multicenter, randomized studies of the efficacy and safety of cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion in moderate to severe dry eye disease.CsA Phase 3 Study Group, Ophthalmology 107 (2000) 631–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Katz G, Springs CL, Craven ER, Montecchi-Palmer M, Ocular surface disease in patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension treated with either BAK-preserved latanoprost or BAK-free travoprost, Clin. Ophthalmol 4 (2010) 1253–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Shin MS, Kim JI, Lee MS, Kim KH, Choi JY, Kang KW, Jung SY, Kim AR, Kim TH, Acupuncture for treating dry eye: a randomized placebo-controlled trial, Acta Ophthalmol. 88 (2010) e328–e333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Vitale S, Goodman LA, Reed GF, Smith JA, Comparison of the NEI-VFQ and OSDI questionnaires in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome-related dry eye, Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2 (2004) 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Luchs JI, Nelinson DS, Macy JI, Efficacy of hydroxypropyl cellulose ophthalmic inserts (LACRISERT) in subsets of patients with dry eye syndrome: findings from a patient registry, Cornea 29 (2010) 1417–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Stevenson D, Tauber J, Reis BL, Efficacy and safety of cyclosporin a ophthalmic emulsion in the treatment of moderate-to-severe dry eye disease: a dose-ranging, randomized trial. The Cyclosporin a phase 2 study group, Ophthalmology 107 (2000) 967–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Davitt WF, Bloomenstein M, Christensen M, Martin AE, Efficacy in patients with dry eye after treatment with a new lubricant eye drop formulation, J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther 26 (2010) 347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Yoon KC, Im SK, Kim HG, You IC, Usefulness of double vital staining with 1% fluorescein and 1% lissamine green in patients with dry eye syndrome, Cornea 30 (2011) 972–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Novack GD, Asbell P, Barabino S, Bergamini MVW, Ciolino JB, Foulks GN, Goldstein M, Lemp MA, Schrader S, Woods C, Stapleton F, TFOS DEWS II clinical trial design report, Ocul. Surf 15 (2017) 629–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].DEWS, The epidemiology of dry eye disease: report of the epidemiology Subcommittee of the International dry eye WorkShop (2007), Ocul. Surf 5 (2007) 93–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Rand A, Pistilli M, Peskin E, Smolen H, Dentone PG, Farrar J, Maguire MG, Asbell PA, Correlation of a global assessment with dry eye questionnaires in evaluating symptoms of dry eye disease, ARVO Meet. Abstr 52 (2011) 3861. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Pistilli M, Ying GS, Maguire MG, Peskin E, Dentone PG, Asbell PA, Symptom questionnaires for dry eye disease: a comparative Rasch analysis of the OSDI, BODI and IDEEL, ARVO Meet. Abstr 52 (2011) 3861. [Google Scholar]

- [66].Cleeland CS, Ryan KM, Pain assessment: global use of the brief pain inventory, Ann. Acad. Med. Singap 23 (1994) 129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Hodson L, Skeaff CM, Fielding BA, Fatty acid composition of adipose tissue and blood in humans and its use as a biomarker of dietary intake, Prog. Lipid Res 47 (2008) 348–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Arab L, Biomarkers of fat and fatty acid intake, J. Nutr 133 (Suppl. 3) (2003) 925S–932S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Kuklinski E, Asbell PA, Sjogren’s syndrome from the perspective of ophthalmology, Clin. Immunol 182 (2017) 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Matossian C, Micucci J, Characterization of the serological biomarkers associated with Sjogren’s syndrome in patients with recalcitrant dry eye disease, Clin. Ophthalmol 10 (2016) 1329–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC, Seror R, Criswell LA, Labetoulle M, Lietman TM, Rasmussen A, Scofield H, Vitali C, Bowman SJ, Mariette X, International Sjogren G, ‘s syndrome criteria working, 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European league against rheumatism classification criteria for primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a consensus and data-driven methodology involving three international patient cohorts, Arthritis Rheum. 69 (2017) 35–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Bhargava R, Kumar P, Oral omega-3 fatty acid treatment for dry eye in contact lens wearers, Cornea 34 (2015) 413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Bhargava R, Kumar P, Phogat H, Kaur A, Kumar M, Oral omega-3 fatty acids treatment in computer vision syndrome related dry eye, Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 38 (2015) 206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Wang L, Chen X, Hao J, Yang L, Proper balance of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid supplements with topical cyclosporine attenuated contact lens-related dry eye syndrome, Inflammopharmacology 24 (2016) 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Harris WS, Pottala JV, Varvel SA, Borowski JJ, Ward JN, McConnell JP, Erythrocyte omega-3 fatty acids increase and linoleic acid decreases with age: observations from 160,000 patients, Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 88 (2013) 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]