Abstract

Purpose

To demonstrate a case of massive vitreous haemorrhage obscuring the underlying diagnosis of a large mixed-cell choroidal melanoma which had undergone spontaneous necrosis.

Case Report

A 49-year-old man in good general health suddenly lost vision in his right eye due to an extensive vitreous haemorrhage 1 day after a workout at the gym. He reported good vision prior to that without any symptoms of flashes, floaters, or shadows. He was referred to the vitreoretinal department of a tertiary eye hospital, where he presented with a drop in vision to light perception only in the right phakic eye. Pars plana vitrectomy was performed in the right eye, which revealed intraoperatively massive retinal ischemia and choroidal haemorrhage, but no obvious tumour mass that could have been biopsied. The vitrectomy cassette specimen was sent for histopathology, where “ghost-like” melanoma cells were identified. The eye was subsequently enucleated, revealing an extensively necrotic and haemorrhagic choroidal melanoma of mixed cell type with only small viable tumour foci at the base and almost complete lysis of the detached retina.

Conclusion

Some uveal melanomas (UMs) undergo spontaneous necrosis due to rapid growth, with the centre of the tumour outstripping its established blood supply in the “watershed area” of the eye, and becoming hypoxic with associated necrosis of intraocular structures. Such UMs are often associated with haemorrhage and/or inflammation and usually cause significant destruction of ocular tissues, resulting in enucleation as the only treatment option.

Keywords: Spontaneous necrosis, Hyphaema, Vitreous haemorrhage, Necrotic melanoma

Established Facts

Spontaneous intraocular haemorrhage can occur due to underlying malignancies, such as choroidal melanoma.

Choroidal melanomas usually demonstrate a solid dome- or mushroom-shaped low-to-medium reflective lesion with a regular internal acoustic structure on ultrasound (US), often with subretinal fluid at the margins. Colour Doppler US frequently shows pulsatile blood flow at the base of the melanoma. None of these features were observed in the case presented.

Rapid growth can occur in monosomy 3 and/or BAP1 mutant melanoma, leading to tumour necrosis, haemorrhage and secondary glaucoma.

Novel Insights

A massive vitreous haemorrhage can obscure the underlying diagnosis of a large choroidal melanoma.

Atypical large choroidal melanomas can occur without any of the above-mentioned characteristics on US.

Rapid expansive growth of a choroidal melanoma does not necessarily equate a “high risk” uveal melanoma but can occur also in spindle cell melanomas with disomy 3 and in the absence of somatic BAP1 mutations.

Introduction

Uveal melanoma (UM) is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults, with an incidence of about 5–8 per million. It commonly occurs unilaterally in Caucasians during the fifth to sixth decade of life [1].

About one-third of UM patients have asymptomatic tumours discovered on routine ophthalmic examination [2]. While symptoms are not common in smaller melanomas, they occur more frequently in larger tumours or lesions near the posterior pole. Common symptoms are photopsia; in more centrally located UMs, visual field defects are described, whilst a decrease in visual acuity is experienced if the macula is affected either by the UM itself or by an accompanying exudative retinal detachment.

Ultrasound (US) is the most important ancillary test in a UM where A-scan shows low-to-medium internal reflectivity with smooth attenuation and vascular pulsations within the tumour, while B-scan usually demonstrates a solid dome- or mushroom-shaped lesion. For tumours >3 mm in thickness, a combination of A- and B-scan US can diagnose UM usually with >95% accuracy [3].

Choroidal melanomas can rarely undergo spontaneous necrosis: this occurs in about 0.5–1% of all UMs [4]. We report a case of unusual presentation of a large choroidal melanoma of mixed cell type which showed atypical US findings.

Case Report

A 49-year-old man in good general health suddenly lost the vision in his right eye 1 day after a workout at the gym. He reported good vision prior to that without any symptoms of flashes, floaters, or shadows; only his wife had noticed that the eye had been red for several days prior to his vision loss.

He developed a severe headache 1 day later and presented to a regional eye unit with hyphaema, vitreous haemorrhage, and a high intraocular pressure of 70 mm Hg for which he twice received paracentesis. A contrast computed tomography scan of the brain did not show any abnormal findings apart from a dense intraocular haemorrhage. A B-scan US was reported as suggestive of posterior scleritis (T-sign) for which the patient was put on prednisolone 60 mg OD.

Since his intraocular haemorrhage did not resolve, the patient was referred to the vitreoretinal department at Manchester Royal Eye Hospital, where he presented with vision of light perception in the right phakic eye, an intraocular pressure of 9 mm Hg, a dense hyphaema with barely any iris visible (Fig. 1a), and no fundus view. The conjunctival and episcleral vessels were dilated and congested (Fig. 1b). The ocular findings of his fellow eye were normal.

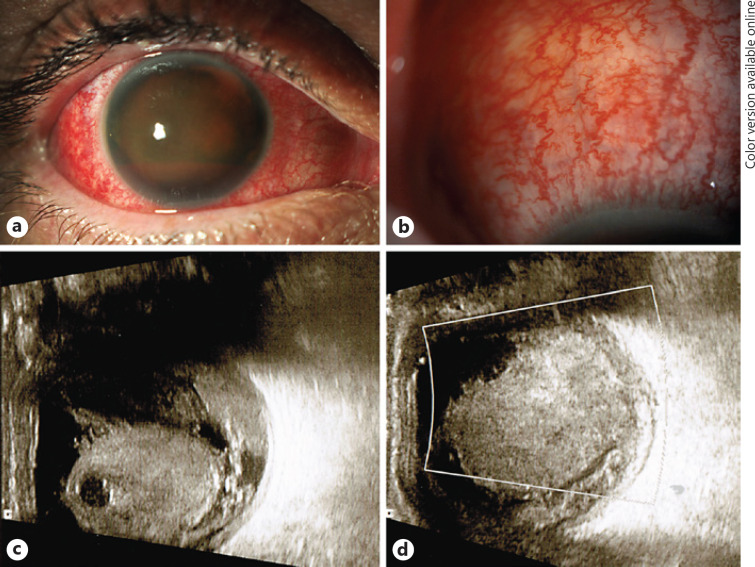

Fig. 1.

a The dense haemorrhagic hyphaema of the right eye of the 49-year-old patient seen on presentation to the tertiary referral clinic. b Congested and dilated “sentinel” vessels in the conjunctiva of the same right eye at higher power. c, d Organised vitreous haemorrhage viewed on ultrasound, with potential connection with the focally thickened choroid.

An US B-scan demonstrated a moderately reflective multiple echo-forming globular mass with lytic spaces in the vitreous cavity with irregular edges and membranous opacities with a broken appearance inferiorly, possibly connected to a choroidal haemorrhage. No clear underlying choroidal mass could be detected (Fig. 1c, d). Doppler scan showed normal flow pattern. The superior ophthalmic vein did not appear enlarged, so there was no hint of a vascular malformation with atrioventricular shunt as the underlying cause for the dense intraocular bleed either. The previously reported T-sign suggestive of posterior scleritis was no longer visible.

The patient was then referred to the Liverpool Ocular Oncology Centre where he underwent vitrectomy, which revealed intraoperatively massive retinal ischaemia and choroidal haemorrhage, but no obvious tumour mass was observed. The vitrectomy cassette specimen was submitted for histopathological examination. In the specimen, numerous melanoma cells of mixed spindle and epithelioid cell type could be identified on a haemorrhagic and lytic cellular background. Immunohistochemical stains showed clear positivity of the tumour cells for MelanA and nuclear reactivity for BAP1 (Fig. 2a, b).

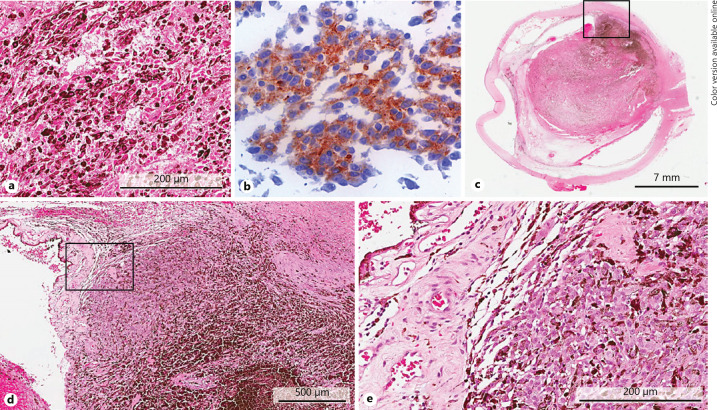

Fig. 2.

a High-power histological section of the endoresection specimen, demonstrating numerous pigmented melanoma cells on a background of lytic tumour cells (H&E stain). b Immunostaining of the endoresection sample showing clear positivity of the tumour cells for MelanA (magnification ×60). c Low-power magnification of the enucleated globe demonstrating a near-total necrotic partially pigmented mass in the posterior segment of the eye, with extensive retinal detachment and fibrinous synechiae between the retina and the distorted posterior iris. d Higher magnification of the inset box in c showing an area of viable tumour (H&E), which is seen better again at higher magnification of the area within the inset box of d in e.

The patient underwent enucleation of the right eye a few days later. Microscopy and histopathology revealed an extensively necrotic and haemorrhagic choroidal melanoma with only a small viable tumour focus remaining, and almost dissolution of the completely detached retina (Fig. 2c–e). The majority of the haemorrhage was in fact “fluid” necrotic tumour.

The small residual focus of viable melanoma cells was seen located at the base of the tumour adjacent to a small capillary, and it demonstrated MelanA and nuclear BAP1 positivity (Fig. 3a). In the necrotic areas, the tumour cells lost their immunoreactivity for these markers.

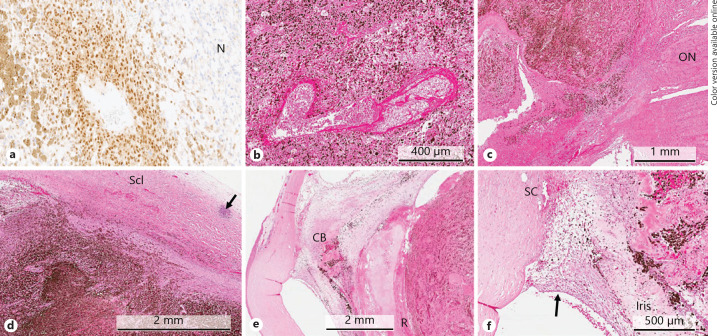

Fig. 3.

a BAP1 immunohistochemical staining showing clear nuclear positivity of the residual tumour cells for this marker. In the necrotic area (N), the melanoma cells lose their reactivity for both MelanA and BAP1 (magnification ×20; DAB chromogen). b A large capillary within the necrotic choroidal melanoma showing fibrinoid necrosis-like changes of its walls (H&E staining). c The necrotic choroidal melanoma at the optic disc showing extensive pigmentation and scattering of melanophages, which extend up to the lamina cribrosa of the optic nerve (ON) (H&E staining). d Scleral (Scl) thickening at the base of the tumour caused by oedema as well as chronic inflammatory infiltrates (arrow). e Proteinaceous fluid is seen between the necrotic choroidal melanoma with the overlying dissolved retina (R) and the posterior surface of the iris leaf and the detached ciliary body (CB) (H&E staining). f An extensive neovascular membrane is present overlying the anterior iris surface and obstructing the chamber angle (arrow). Schlemm's canal (SC) is filled with blood.

Other intratumoural blood vessels demonstrate fibrinoid necrosis-like changes (Fig. 3b). Scattered within and around the tumour were numerous melanophages, which also were seen close the lamina cribrosa of the optic nerve (Fig. 3c) and sclera. Thickening of the sclera at the base of the tumour with scattered lymphocytic infiltrates and haemorrhage was also observed (Fig. 3d). Otherwise, the enucleated globe demonstrated extensive degenerative changes associated with the necrotic and haemorrhagic tumour, including proteinaceous exudate within the anterior vitreous, detachment of the ciliary body (Fig. 3e), and iridis rubeosis with closure of the angles (Fig. 3f).

Microsatellite analysis and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification [5, 6] of the DNA extracted from the tumour cells of both the endoresection and the enucleation sample showed disomy 3. The other chromosomal changes of the UM cells were disomy chromosome 1p, polysomy 6p, and disomy 8. The patient was considered to have a low-to-intermediate risk of developing liver metastasis. He is now 24 months follow-up without evidence of liver lesions on US/magnetic resonance imaging.

Since the patient had been treated with two anterior chamber paracenteses prior to the enucleation, he underwent external beam photon radiotherapy in order to decrease the risk of melanoma seeding and orbital recurrence.

Discussion

This case report documents an atypical presentation of a large choroidal melanoma that underwent near-total spontaneous necrosis leading to large intraocular haemorrhage in the absence of prior visual symptoms until the event. Other unusual features of this case include the US findings, which were misleading.

Spontaneous necrosis of choroidal melanomas is very rare, varying between 0.5 and 1% of all UMs [4]. The incidence of totally necrotic UMs has been reported at 3.6% and that of partially necrotic UMs as 5.7% in previous studies [7]. These tumours are usually associated with significant haemorrhage and/or inflammation [4, 8]. In 6 cases of spontaneous necrosis in UM examined by Thareja et al. [4], >90% of the UM mass was necrotic in all cases, with only viable cells being present at the basal edges. We reviewed the database of 1,377 primary enucleated eyes treated for UM at the Liverpool Ocular Oncology Centre at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital and ascertained that only 5 (0.5%) underwent spontaneous necrosis, with most demonstrating at least 80% tumour lysis.

As reported in the literature, the patients with spontaneous UM typically present with severe pain, haemorrhage, and inflammation and usually require enucleation. Almost all reported cases of spontaneously necrotic choroidal melanomas also exhibited ischemic necrosis of the iris and ciliary body as well as of the retina. Vasculitis or inflammation of the tumour itself could not be detected. About 3% of necrotic UMs initially present with some form of intraocular haemorrhage, and some present with raised intraocular pressure, as seen in our case [9]. Scleritis and episcleritis are often associated with total UM necrosis and are both present together in >75% of cases, whereas only 5% of cases have neither episcleritis nor scleritis [10, 11].

US is normally a very helpful diagnostic imaging modality for determining the presence of a UM, even in opaque ocular media, and on B-scan mode characteristically demonstrates a solid dome- or mushroom-shaped lesion with a regular internal acoustic structure because of its cellular, homogeneous architecture, often with subretinal fluid at its margins. The A-scan mode usually displays low-to-medium reflectivity of the lesion, with large ocular melanomas often producing internal sound attenuation. Colour Doppler US frequently shows pulsatile blood flow at the base of the melanoma [12]. None of these features were observed in our patient. Here, US examination demonstrated a moderately reflective globular mass with multiple cysts in the vitreous cavity, with irregular edges and membranous opacities with a broken appearance inferiorly, representing an organised vitreous haemorrhage with possible connection to a choroidal haemorrhage inferiorly in the sense of a breakthrough bleed. No definitive underlying choroidal lesion could be detected. Further, Doppler scan showed normal flow pattern.

The mechanism of infarction and necrosis of UMs and ocular structures is not fully understood. One mechanism that has been discussed involves the concept of “watershed infarction” of UMs typically located at the equator. The choroid is supplied by the short posterior ciliary artery, the iris, and the ciliary body by the long posterior ciliary artery via anastomosis at the ciliary plexus with the anterior ciliary artery (all branches being fed by the ophthalmic artery). “Watershed” infarction of a UM requires vascular compromise from both the anterior and posterior circulation of the eye. The complete infarction of UMs observed in previous studies is likely to have progressed from watershed infarctions that spread to include the entire tumours as ischemia continued. If any intact tumour cells were found in the necrotic melanoma, they tended to be located at the tumour periphery, thus supporting the concept of watershed ischemic necrosis in the centre of the tumour with outward expansion of ischemic necrosis. This is further supported by a lack of thrombi in the long posterior ciliary arteries, short posterior ciliary arteries, and the major circle of the iris in all their specimens [4, 13].

Another mechanism proposed is that the tumour mass of the UM raises intraocular pressure, leading to acute angle closure, vascular compromise, and ischemia of the ocular contents [13]. Further, it has been proposed that a UM grows too rapidly and outstrips its blood supply and becomes necrotic. This leads to the release of cytotoxic products triggered by the necrosis, which lead to vasculitis of intraocular vessels and consequently to infarction, swelling, and cellulitis of ocular and extraocular tissues. This would represent the spontaneous version of toxic tumour syndrome, which is induced via proton beam when administered to large tumours [14]. Vasculitis provides a potential explanation for the infarction of both the anterior and posterior choroid, which typically avoid vascular compromise due to vessel anastomoses [13, 15]. Sudden infarction then leads to the acute pain often experienced by the patients. This is likely to have occurred in our case.

On histology most spontaneously necrotic UMs demonstrate large “geographical areas” of necrosis composed of melanoma ghost cells surrounded by zones of pigmented macrophages. Intratumoural thrombi within the UM were not usually found [4, 9], as in our case. It is difficult to determine the cell morphology of the infarcted UM because of the extent of the necrosis and associated cellular oedema. However, in this case and others, we have seen mixed cell morphologies. Our current case demonstrated a “low-grade” UM, i.e., one with chromosomal alterations and nuclear BAP1 immunohistochemistry typically associated with a good prognosis [16]. In contrast is another interesting example, namely the case published by Callejo et al. [17] of a rapidly growing posterior UM, which was ∼85% necrotic with the residual basal viable component being spindle and disomy 3, whilst the apical portion of viable cells was epithelioid and monosomy 3.

Whilst it could be hypothesised that, in the current case, an aggressive clone (possibly monosomy 3 and nuclear BAP1 negative) of choroidal melanoma cells may have proliferated more rapidly, pushing through and causing the extensive necrosis and ocular damage, our experience is that most choroidal melanomas do not display notable heterogeneity, neither for chromosomal aberrations nor for BAP1 immunohistochemistry [18, 19]. These findings have been supported by others [20, 21, 22]. New single sequencing techniques may provide further data to understand choroidal melanoma progression in the future.

Conclusions

Some UMs may be predisposed to spontaneous necrosis due to rapid growth, with the centre of the tumour outgrowing its established blood supply in the “watershed” area and becoming hypoxic. The ischemic necrosis of the tumour then results in the release of cytokines with further necrosis, swelling, and inflammation in the surrounding tissues. This in turn may lead to anterior displacement of the lens iris diaphragm with increased intraocular pressure, which potentiates further tumour necrosis with associated necrosis of the iris, ciliary body, and retina.

Statement of Ethics

The patient consented to the use of the clinical data and photographs as well as the use of the histopathological images for publication.

Disclosure Statement

None of the authors has any financial relationship or conflict of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to the thanks the technical support by Mr. Simon Biddolph and Dr. Sophie Thornton of the Liverpool Clinical Laboratories, Royal Liverpool University Hospital, for the preparation of the slides and the molecular testing of the tumour material, respectively.

References

- 1.Scotto J, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Lee JA. Melanomas of the eye and other noncutaneous sites: epidemiologic aspects. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976 Mar;56((3)):489–91. doi: 10.1093/jnci/56.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damato EM, Damato BE. Detection and time to treatment of uveal melanoma in the United Kingdom: an evaluation of 2,384 patients. Ophthalmology. 2012 Aug;119((8)):1582–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Char DH, Stone RD, Irvine AR, Crawford JB, Hilton GF, Lonn LI, et al. Diagnostic modalities in choroidal melanoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980 Feb;89((2)):223–30. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(80)90115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thareja S, Rashid A, Grossniklaus HE. Spontaneous Necrosis of Choroidal Melanoma. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2014 Oct;1((1)):63–9. doi: 10.1159/000366559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Versluis M, de Lange MJ, van Pelt SI, Ruivenkamp CA, Kroes WG, Cao J, et al. Digital PCR validates 8q dosage as prognostic tool in uveal melanoma. PLoS One. 2015 Mar;10((3)):e0116371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angi M, Kalirai H, Taktak A, Hussain R, Groenewald C, Damato BE, et al. Prognostic biopsy of choroidal melanoma: an optimised surgical and laboratory approach. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017 Aug;101((8)):1143–6. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bujara K. Necrotic malignant melanomas of the choroid and ciliary body. A clinicopathological and statistical study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1982;219((1)):40–3. doi: 10.1007/BF02159979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palamar M, Thangappan A, Shields CL, Ehya H, Shields JA. Necrotic choroidal melanoma with scleritis and choroidal effusion. Cornea. 2009 Apr;28((3)):354–6. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181875463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser DJ, Jr, Font RL. Ocular inflammation and hemorrhage as initial manifestations of uveal malignant melanoma. Incidence and prognosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979 Jul;97((7)):1311–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1979.01020020053012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moshari A, Cheeseman EW, McLean IW. Totally necrotic choroidal and ciliary body melanomas: associations with prognosis, episcleritis, and scleritis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001 Feb;131((2)):232–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00783-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhagat S, Ramaesh K, Wharton SB, Dhillon B. Spontaneous acute scleritis and scleral necrosis in choroidal malignant melanoma. Eye (Lond) 1999 Dec;13((Pt 6)):793–5. doi: 10.1038/eye.1999.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ossoinig KC, Bigar F, Kaefring SL. Malignant melanoma of the choroid and ciliary body. A differential diagnosis in clinical echography. Bibl Ophthalmol. 1975;83((83)):141–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brannan S, Browne B, Clark BJ. Massive infarction of ocular tissues complicating a necrotic uveal melanoma. Eye (Lond) 1998;12((Pt 2)):324–5. doi: 10.1038/eye.1998.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groenewald C, Konstantinidis L, Damato B. Effects of radiotherapy on uveal melanomas and adjacent tissues. Eye (Lond) 2013 Feb;27((2)):163–71. doi: 10.1038/eye.2012.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reese AB, Archila EA, Jones IS, Cooper WC. Necrosis of malignant melanoma of the choroid. Am J Ophthalmol. 1970 Jan;69((1)):91–104. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(70)91860-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farquhar N, Thornton S, Coupland SE, Coulson JM, Sacco JJ, Krishna Y, et al. Patterns of BAP1 protein expression provide insights into prognostic significance and the biology of uveal melanoma. J Pathol Clin Res. 2017 Nov;4((1)):26–38. doi: 10.1002/cjp2.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callejo SA, Dopierala J, Coupland SE, Damato B. Sudden growth of a choroidal melanoma and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification findings suggesting late transformation to monosomy 3 type. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011 Jul;129((7)):958–60. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalirai H, Dodson A, Faqir S, Damato BE, Coupland SE. Lack of BAP1 protein expression in uveal melanoma is associated with increased metastatic risk and has utility in routine prognostic testing. Br J Cancer. 2014 Sep;111((7)):1373–80. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coupland SE, Kalirai H, Ho V, Thornton S, Damato BE, Heimann H. Concordant chromosome 3 results in paired choroidal melanoma biopsies and subsequent tumour resection specimens. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015 Oct;99((10)):1444–50. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koopmans AE, Verdijk RM, Brouwer RW, van den Bosch TP, van den Berg MM, Vaarwater J, et al. Clinical significance of immunohistochemistry for detection of BAP1 mutations in uveal melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2014 Oct;27((10)):1321–30. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van de Nes JA, Nelles J, Kreis S, Metz CH, Hager T, Lohmann DR, et al. Comparing the Prognostic Value of BAP1 Mutation Pattern, Chromosome 3 Status, and BAP1 Immunohistochemistry in Uveal Melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016 Jun;40((6)):796–805. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szalai E, Wells JR, Ward L, Grossniklaus HE. Uveal Melanoma Nuclear BRCA1-Associated Protein-1 Immunoreactivity Is an Indicator of Metastasis. Ophthalmology. 2018 Feb;125((2)):203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]