Abstract

Background

Patients with uveal melanoma (UM) are known to have quality of life (QOL) issues after treatment, but QOL concerns after initial diagnosis are ill-defined.

Objectives

We studied the QOL concerns of patients with UM after initial diagnosis to identify factors associated with QOL.

Method

Between September 2011 and May 2016, UM planning to undergo radiotherapy completed the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) core quality of life questionnaire (QLQ)-C30, as well as the Ophthalmic Oncology module, QLQ-OPT30. Demographic, ophthalmic, and tumor related characteristics were recorded. The primary outcome was the QOL score and fraction of patients reporting any or severe symptoms. A multiple stepwise regression model investigated the association of demographic, ophthalmic, and tumor characteristics with QOL.

Results

QOL concerns were assessed in 201 subjects. The majority (51/60) of QOL items had a high response rate (≥90%), and internal consistency on scales (median Cronbach α = 0.85) with the most common severe QOL concern being worry about disease recurrence (41%). The most common ophthalmic symptoms reported were vision impairment (81%) and ocular irritation (66%). Multivariable regression modeling demonstrated several significant associations.

Conclusions

Severe worry about UM recurrence, ocular irritation, and vision impairment was reported by many patients. Clinicians should be aware of these concerns and implement management strategies.

Keywords: Uveal melanoma, Quality of life, Surveys and questionnaires

Introduction

After initial diagnosis, most localized uveal melanoma (UM) is treated with surgery or radiotherapy. The 10-year metastasis-free and overall survival (OS) rate is approximately 87 and 65%, respectively, for medium-sized tumors, regardless of treatment approach [1, 2]. For this reason, treatment is often guided by its effect on the quality of life (QOL). QOL of patients with UM has been analyzed in several studies. Most analyses have focused on the effect of treatment on QOL [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15], with only a few attempting to characterize the QOL of UM patients after initial diagnosis and prior to treatment [16, 17, 18]. Moreover, factors associated with QOL concerns of UM patients after initial diagnosis are poorly characterized. A variety of instruments have been used to the assess the QOL of UM patients, with the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Ophthalmic Oncology Task Force (OOTF) module developed specifically for these patients [6]. Recognizing the QOL concerns of patients after initial diagnosis may be critical to enabling early intervention that may prevent a further decline in QOL after treatment.

We conducted this study to better characterize the QOL concerns of patients with UM after initial diagnosis. For the first time, we report general and ophthalmic QOL of a cohort of UM patients in the USA using the EORTC instruments as well as demographic, ophthalmic, and tumor factors associated with QOL in these patients.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Assessments

With approval from the institutional review board (#16-991), this analysis of prospectively collected QOL data was conducted. All consecutively evaluated UM patients at our institution referred for radiotherapy between September 2011 and May 2016 were eligible for study. Patients that chose not to complete QOL assessments or who could not read or speak English (n = 13, 5.2% of those evaluated) were ineligible for study.

All patients were evaluated by an ophthalmic oncologist to confirm the diagnosis and extent of UM and for management counseling. Patients with primary tumors amenable to radiotherapy were subsequently referred to a radiation oncologist to discuss plaque brachytherapy, generally within a week of the ophthalmic assessment. As part of the radiation oncology clinical evaluation, QOL and comorbidity assessments were performed prospectively. All patients completed the English version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ)-C30 (version 3), as well as the Ophthalmic Oncology module, QLQ-OPT30 (1999 version). Patient comorbidities were coded according to the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation (ACE)27. Demographic, ophthalmic, and tumor-related characteristics were recorded for each patient.

Statistical Analysis

The minimum sample size for multivariable analysis was estimated to be 200 based on planned multivariable analyses of 2 questionnaires [19]. Responses to the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-OPT30 items were recorded as raw data, assigned to previously defined scales (Table 1), and then linearly transformed to scale scores ranging from 0 to 100 (Table 2). For functional scales and global health, higher values represent superior QOL, while for symptom scales, higher values represent inferior QOL. Severe QOL concerns were defined as those occurring “quite a bit” or “very much” (a score of 3 or 4 on a scale of 1–4). Missing data were imputed for scale scores when at least 50% of the scale items were reported; if >50% of the scale items were missing, the score was not included in the analysis. Cronbach's α coefficient was calculated to estimate the internal consistency of responses in the population sampled. Summary statistics are presented. Associations between QOL scores and independent variables were assessed by multiple stepwise regression models. Calculations were performed using WinSTAT® for Excel (v2007.1).

Table 1.

Items and responses from the EORTC Core Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) and the Ophthalmic Oncology Module (OPT30)

| Items | Scales/Items | Items, range | With data, n (%) | With severe concerns n (%) | With concerns n (%) | Raw score mean | Raw score SD | Raw score median | Raw score (25th percentile) | Raw score (75th percentile) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Do you have any trouble doing strenuous activities, like carrying a heavy shopping bag or a suitcase? | physical functioning | 3 | 199 (99) | 24 (12) | 58 (29) | 1.47 | 0.85 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 2. Do you have any trouble taking a long walk? | physical functioning | 3 | 200 (100) | 27 (14) | 53 (27) | 1.46 | 0.86 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 3. Do you have any trouble taking a short walk outside of the house? | physical functioning | 3 | 199 (99) | 6 (3) | 25 (13) | 1.17 | 0.51 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4. Do you need to stay in bed or a chair during the day? | physical functioning | 3 | 198 (99) | 5 (3) | 16 (8) | 1.12 | 0.47 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5. Do you need help with eating dressing, washing yourself, or using the toilet? | physical functioning | 3 | 191 (95) | 1 (1) | 5 (3) | 1.04 | 0.27 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6. Were you limited in doing either your work or other daily activities? | role functioning | 3 | 197 (98) | 13 (7) | 34 (17) | 1.26 | 0.66 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7. Were you limited in pursuing your hobbies or other leisure time activities? | role functioning | 3 | 198 (99) | 15 (8) | 39 (20) | 1.30 | 0.70 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8. Were you short of breath? | dyspnea | 3 | 198 (99) | 6 (3) | 44 (22) | 1.26 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 9. Have you had pain? | pain | 3 | 199 (99) | 18 (9) | 50 (25) | 1.38 | 0.76 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 |

| 10. Did you need to rest? | fatigue | 3 | 197 (98) | 17 (9) | 62 (31) | 1.44 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 11. Have you had trouble sleeping? | insomnia | 3 | 199 (99) | 29 (15) | 99 (50) | 1.68 | 0.80 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 12. Have you felt weak? | fatigue | 3 | 196 (98) | 11 (6) | 40 (20) | 1.28 | 0.61 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 13. Have you lacked appetite? | appetite | 3 | 199 (99) | 2 (1) | 31 (16) | 1.17 | 0.40 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 14. Have you felt nauseated? | nausea and vomiting | 3 | 199 (99) | 1 (1) | 10 (5) | 1.06 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 15. Have you vomited? | nausea and vomiting | 3 | 200 (100) | 0 (0) | 4 (2) | 1.02 | 0.13 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 16. Have you been constipated? | constipation | 3 | 199 (99) | 8 (4) | 22 (11) | 1.16 | 0.48 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 17. Have you had diarrhea? | diarrhea | 3 | 198 (99) | 2 (1) | 20 (10) | 1.12 | 0.38 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 18. Were you tired? | fatigue | 3 | 200 (100) | 21 (11) | 80 (40) | 1.52 | 0.72 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 19. Did pain interfere with your daily activities? | pain | 3 | 196 (98) | 11 (6) | 24 (12) | 1.20 | 0.60 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 20. Have you had difficulty in concentrating on things, like reading a newspaper or watching television? | cognitive functioning | 3 | 198 (99) | 15 (8) | 65 (33) | 1.41 | 0.67 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 21. Did you feel tense? | emotional functioning | 3 | 200 (100) | 24 (12) | 112 (56) | 1.70 | 0.74 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 22. Did you worry? | emotional functioning | 3 | 200 (100) | 51 (26) | 142 (71) | 2.02 | 0.84 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 23. Did you feel irritable? | emotional functioning | 3 | 198 (99) | 12 (6) | 66 (33) | 1.42 | 0.68 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 24. Did you feel depressed? | emotional functioning | 3 | 200 (100) | 14 (7) | 77 (39) | 1.48 | 0.69 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 25. Have you had difficulty remembering things? | cognitive functioning | 3 | 198 (99) | 11 (6) | 49 (25) | 1.32 | 0.63 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 26. Has your physical condition or medical treatment interfered with your family life? | social functioning | 3 | 199 (99) | 10 (5) | 37 (19) | 1.26 | 0.63 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 27. Has your physical condition or medical treatment interfered with your social activities? | social functioning | 3 | 199 (99) | 11 (6) | 44 (22) | 1.30 | 0.65 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 28. Has your physical condition or medical treatment caused you financial difficulties? | financial difficulties | 3 | 197 (98) | 19 (10) | 42 (21) | 1.36 | 0.80 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 29. How would you rate your overall health during the past week? | global health status | 6 | 198 (99) | 17 (9) | 195 (98) | 5.54 | 1.35 | 6 | 5 | 7 |

| 30. How would you rate your overall quality of life during the past week? | global health status | 6 | 197 (98) | 18 (9) | 193 (98) | 5.59 | 1.39 | 6 | 5 | 7 |

| 31. Did you have the sensation of grittiness or the feeling of a foreign body in the treated eye? | ocular irritation | 3 | 196 (98) | 20 (10) | 52 (27) | 1.40 | 0.76 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 32. Did you feel any pain, soreness, or discomfort in or around the treated eye? | ocular irritation | 3 | 199 (99) | 14 (7) | 54 (27) | 1.35 | 0.64 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 33. Did you have any itching in your treated eye? | ocular irritation | 3 | 196 (98) | 10 (5) | 48 (24) | 1.30 | 0.58 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 34. Did watering in the treated eye trouble you? | ocular irritation | 3 | 195 (97) | 9 (5) | 31 (16) | 1.21 | 0.53 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 35. Were you troubled by any discharge from your treated eye? | ocular irritation | 3 | 192 (96) | 4 (2) | 13 (7) | 1.09 | 0.39 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 36. Did you suffer from dryness in your treated eye? | ocular irritation | 3 | 193 (96) | 9 (5) | 38 (20) | 1.25 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 37. Were you troubled by any defects in your side vision? | vision impairment | 3 | 193 (96) | 34 (18) | 66 (34) | 1.61 | 0.98 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 38. Were you troubled by double vision when looking straight ahead? | vision impairment | 3 | 192 (96) | 12 (6) | 33 (17) | 1.26 | 0.65 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 39. Were you troubled by double vision when looking sideways? | vision impairment | 3 | 191 (95) | 11 (6) | 26 (14) | 1.22 | 0.63 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 40. Did you have headaches? | headaches | 3 | 194 (97) | 12 (6) | 56 (29) | 1.37 | 0.66 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 41. Were you worried about your health in the future? | worry about recurrent disease | 3 | 192 (96) | 87 (45) | 160 (83) | 2.49 | 1.00 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 42. Were you worried about a tumor recurring in other areas of the body? | worry about recurrent disease | 3 | 195 (97) | 92 (47) | 157 (81) | 2.52 | 1.05 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 43. Were you worried about losing the eye? | worry about recurrent disease | 3 | 195 (97) | 78 (40) | 138 (71) | 2.33 | 1.12 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 44. Has your appearance bothered you? | problems with appearance | 3 | 188 (94) | 12 (6) | 33 (18) | 1.26 | 0.65 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 45. Were you dissatisfied with the cosmetic result of the surgery? | problems with appearance | 3 | 119 (59) | 3 (3) | 6 (5) | 1.08 | 0.40 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 46. Did you have difficulty pouring (e.g., tea or coffee)? | functional problems due to vision impairment | 3 | 186 (93) | 4 (2) | 15 (8) | 1.11 | 0.40 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 47. Did you have difficulty seeing to walk in crowded areas? | functional problems due to vision impairment | 3 | 191 (95) | 11 (6) | 33 (17) | 1.24 | 0.57 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 48. Did you have any difficulty with steps or pavements? | functional problems due to vision impairment | 3 | 189 (94) | 16 (8) | 45 (24) | 1.34 | 0.69 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 49. Did you have any difficulty walking downstairs or on uneven ground? | functional problems due to vision impairment | 3 | 189 (94) | 21 (11) | 49 (26) | 1.40 | 0.78 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 50. Did you have difficulty judging distances? | functional problems due to vision impairment | 3 | 191 (95) | 21 (11) | 57 (30) | 1.42 | 0.73 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 51. Were your activities limited in any way because of your vision? | functional problems due to vision impairment | 3 | 191 (95) | 20 (10) | 56 (29) | 1.44 | 0.79 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 52. Did you have difficulty reading because of your vision? | problems with reading | 3 | 195 (97) | 34 (17) | 94 (48) | 1.71 | 0.87 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 53. Did things appear distorted out of your treated eye? | vision impairment | 3 | 156 (78) | 39 (25) | 69 (44) | 1.83 | 1.09 | 1 | 1 | 2.25 |

| 54. Did you see flashes or balls of light with your treated eye? | vision impairment | 3 | 163 (81) | 33 (20) | 84 (52) | 1.81 | 0.97 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 55. Did you see floaters with your treated eye? | vision impairment | 3 | 165 (82) | 47 (28) | 94 (57) | 1.98 | 1.04 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 56. Did your eye feel uncomfortable in bright light? | ocular irritation | 3 | 164 (82) | 27 (16) | 81 (49) | 1.77 | 0.97 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 57. Did the vision of the treated eye interfere with that of the other eye? | vision impairment | 3 | 160 (80) | 17 (11) | 43 (27) | 1.42 | 0.81 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 58. Were you worried about the tumor recurring in the treated eye? | worry about recurrent disease | 3 | 162 (81) | 65 (40) | 111 (69) | 2.29 | 1.11 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 59. Did you have difficulty driving in daylight because of your vision? | problems with driving | 3 | 160 (80) | 15 (9) | 36 (23) | 1.38 | 0.81 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 60. Did you have difficulty driving in the dark because of your vision? | problems with driving | 3 | 158 (79) | 24 (15) | 66 (42) | 1.65 | 0.93 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

Items 1–30 are from the QLQ-C30 (v3.0) and items 31–60 are from the QLQ-OPT30 (©1999). EORTC, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer.

Table 2.

Global health and functional and symptoms scales/items from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Core Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) and the Ophthalmic Oncology Module (QLQ-OPT30)

| Item No. | Items, n | Items, range | Cronbach's α | With severe concerns, n (%) | With concerns, n (%) | Mean | SD | Median | 25th percentile | 75th percentile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global health status | 29, 30 | 2 | 6 | 0.90 | 19 (10) | 156 (79) | 76.1 | 21.7 | 83.3 | 66.7 | 91.7 |

| Functional scales | |||||||||||

| Physical functioning | 1–5 | 5 | 3 | 0.87 | 7 (4) | 69 (35) | 91.5 | 17.0 | 100.0 | 93.3 | 100.0 |

| Role functioning | 6, 7 | 2 | 3 | 0.86 | 12 (6) | 46 (23) | 90.4 | 21.5 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Emotional functioning | 21–24 | 4 | 3 | 0.83 | 14 (7) | 153 (76) | 78.1 | 20.2 | 83.3 | 66.7 | 91.7 |

| Cognitive functioning | 20, 25 | 2 | 3 | 0.64 | 6 (3) | 85 (43) | 87.8 | 18.5 | 100.0 | 83.3 | 100.0 |

| Social functioning | 26, 27 | 2 | 3 | 0.87 | 10 (5) | 54 (27) | 90.6 | 20.1 | 100.0 | 83.3 | 100.0 |

| Symptom scales/items | |||||||||||

| Fatigue | 10, 12, 18 | 3 | 3 | 0.86 | 13 (7) | 91 (46) | 13.9 | 21.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 22.2 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 14, 15 | 2 | 3 | 0.19 | 0 (0) | 13 (7) | 1.2 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Pain | 9, 19 | 2 | 3 | 0.84 | 12 (6) | 51 (26) | 9.9 | 21.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.7 |

| Dyspnea | 8 | 1 | 3 | − | 6 (3) | 44 (22) | 8.8 | 18.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Insomnia | 11 | 1 | 3 | − | 29 (15) | 99 (50) | 22.5 | 26.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 33.3 |

| Appetite loss | 13 | 1 | 3 | − | 2 (1) | 31 (16) | 5.5 | 13.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Constipation | 16 | 1 | 3 | − | 8 (4) | 22 (11) | 5.2 | 16.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Diarrhea | 17 | 1 | 3 | − | 2 (1) | 20 (10) | 3.9 | 12.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Financial difficulties | 28 | 1 | 3 | − | 19 (10) | 42 (21) | 12.1 | 26.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Ocular irritation | 31–36, 56 | 7 | 3 | 0.77 | 5 (3) | 130 (66) | 10.9 | 13.8 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 14.3 |

| Vision impairment | 37–39, 53–55, 57 | 7 | 3 | 0.81 | 15 (9) | 136 (81) | 20.2 | 20.7 | 14.3 | 4.8 | 28.6 |

| Headaches | 40 | 1 | 3 | − | 12 (6) | 56 (29) | 12.3 | 22.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 33.3 |

| Worry about recurrent disease | 41–43, 58 | 4 | 3 | 0.86 | 80 (41) | 181 (92) | 47.1 | 30.0 | 41.7 | 25.0 | 72.9 |

| Problems driving | 59–60 | 2 | 3 | 0.88 | 16 (10) | 67 (41) | 16.9 | 26.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 33.3 |

| Problems with appearance | 44–45 | 2 | 3 | 0.38 | 9 (5) | 34 (18) | 7.7 | 19.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Functional problems due to vision impairment | 46–51 | 6 | 3 | 0.85 | 11 (6) | 89 (46) | 11.0 | 18.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.7 |

| Problems with reading | 52 | 1 | 3 | − | 34 (17) | 94 (48) | 23.7 | 29.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 33.3 |

Results

Patient Characteristics

Assessments were completed by 201 patients with UM after diagnosis and prior to treatment with radiotherapy. Demographic, ophthalmic, and tumor characteristics are presented in Table 3, and represent a typical cohort of UM patients. Median age was 61 years (range 28–89). Almost all patients were white (94.5%) and not Hispanic (95.0%). Most patients were married (61.7%), had children (71.6%), and harbored at least 1 comorbid medical ailment according to the ACE27 (75.1%). Similar proportions of men (55.2%) and women (44.8%) harboring melanoma of the left (47.3%) and right (52.7%) eye were studied. The median visual acuity in the eye with melanoma was 20/30 and it was 20/25 in the eye without melanoma. Choroidal involvement of the uvea (94.0%) predominated; a small proportion of tumors involved the ciliary body (19.9%) and iris (4.5%). Median tumor apical height was 4.4 mm (range 1.1–13.3) and median longest base diameter was 12 mm (range 4.1–22). Most tumors were dome-shaped (81.1%), without extrascleral extension (97.0%) or associated retinal detachment (72.6%), and they spanned the equator with variable proximities to the foveola and optic nerve. According to the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) staging system, most tumors were of a medium size (71.1%). According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system, most tumors were T2 (40.8%) and stage group IIA (40.3%).

Table 3.

Demographic, ophthalmic, and tumor characteristics of the cohort studied

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| <50 years | 44 (22) |

| 50–59 years | 45 (22) |

| 60–69 years | 61 (30) |

| 70–79 years | 29 (14) |

| ≥80 years | 22 (11) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 90 (45) |

| Male | 111 (55) |

| Race | |

| White | 190 (95) |

| Black | 2 (1) |

| Asian | 2 (1) |

| Unknown | 7 (3) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 191 (95) |

| Hispanic | 10 (5) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 124 (62) |

| Not married | 77 (38) |

| Children | |

| Yes | 144 (72) |

| No | 57 (28) |

| Karnofsky performance status | |

| 100 | 34 (17) |

| 90 | 133 (66) |

| 80 | 22 (11) |

| 70 | 8 (4) |

| 60 | 4 (2) |

| Comorbidity severity | |

| No comorbidities | 50 (25) |

| Mild | 81 (40) |

| Moderate | 46 (23) |

| Severe | 24 (12) |

| Visual acuity in eye with melanoma | |

| ≥20/20 | 36 (18) |

| 20/25–20/32 | 72 (36) |

| 20/40–20/160 | 61 (30) |

| ≤20/200 | 32 (16) |

| Visual acuity in eye without melanoma | |

| ≥20/20 | 83 (41) |

| 20/25–20/32 | 98 (49) |

| 20/40–20/160 | 19 (9) |

| ≤20/200 | 1 (0) |

| Visual acuity in best functioning eye | |

| ≥20/20 | 92 (46) |

| 20/25–20/32 | 93 (46) |

| 20/40–20/160 | 16 (8) |

| ≤20/200 | 0 (0) |

| Intraocular pressure in eye with melanoma | |

| <22 | 193 (96) |

| >21 | 8 (4) |

| Intraocular pressure in eye without melanoma | |

| <22 | 199 (99) |

| >21 | 2 (1) |

| Eye with melanoma | |

| Left | 95 (47) |

| Right | 106 (53) |

| Uveal involvement by tumor | |

| Choroid only | 159 (79) |

| Ciliary body only | 4 (2) |

| Iris only | 2 (1) |

| Choroid and ciliary body | 29 (14) |

| Ciliary body and iris | 6 (3) |

| Choroid, ciliary body and iris | 1 (0) |

| Tumor apical height | |

| <2.5 mm | 19 (9) |

| 2.5–5.0 mm | 99 (49) |

| 5.1–7.5 mm | 37 (18) |

| 7.6–10.0 mm | 24 (12) |

| >10.0 mm | 22 (11) |

| Longest tumor basal diameter | |

| <4.5 mm | 1 (0) |

| 4.5–8.0 mm | 28 (14) |

| 8.1–11.0 mm | 31 (15) |

| 11.1–14.0 mm | 89 (44) |

| 14.1–16.0 mm | 24 (12) |

| >16.0 | 28 (14) |

| Tumor shape | |

| Dome | 163 (81) |

| Mushroom | 33 (16) |

| Placoid | 5 (2) |

| Retinal detachment | |

| Yes | 55 (27) |

| No | 146 (73) |

| Extrascleral extension of tumor | |

| Yes | 6 (3) |

| No | 195 (97) |

| Tumor anterior border | |

| Iris | 8 (4) |

| Ciliary body | 35 (17) |

| Equator to ora serrata | 105 (52) |

| Posterior to equator | 53 (26) |

| Tumor posterior border | |

| Iris | 2 (1) |

| Ciliary body | 5 (2) |

| Equator to ora serrata | 11 (5) |

| Posterior to equator | 183 (91) |

| Tumor distance from optic nerve | |

| <2 mm | 49 (24) |

| 2.1–4 mm | 40 (20) |

| 4.1–6 mm | 24 (12) |

| 6.1–8 mm | 26 (13) |

| >8 mm | 62 (31) |

| Tumor distance from foveola | |

| 0 mm | 27 (13) |

| 0.1–2 mm | 34 (17) |

| 2.1–5 mm | 34 (17) |

| 5.1–8 mm | 49 (24) |

| >8 mm | 57 (28) |

| AJCC T stage | |

| T1 | 53 (26) |

| T2 | 82 (41) |

| T3 | 53 (26) |

| T4 | 13 (6) |

| AJCC stage group | |

| I | 45 (22) |

| IIA | 81 (40) |

| IIB | 43 (21) |

| IIIA | 18 (9) |

| IIIB | 11 (5) |

| IV | 3 (1) |

| COMS primary tumor stage | |

| Small | 19 (9) |

| Medium | 143 (71) |

| Large | 39 (19) |

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; COMS, Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study.

Individual Item Responses

Table 1 summarizes responses to the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-OPT30. The majority of items (51/60) had a response rate of ≥90% among the 201 patients studied. Patients were significantly more likely to complete the QLQ-C30 than the QLQ-OPT30, with 99% of items completed on the QLQ-C30 and 90% on the QLQ-OPT30 (p < 0.05, unpaired t test). On the QLQ-C30, the most common item to cause severe QOL concern was “worry” and was endorsed by 26% of patients. Likewise, on the QLQ-OPT30, the 4 items comprising the “worry about recurrent disease” scale were the most likely to cause severe concern and were endorsed by 40–47% of patients.

Composite Scale Responses

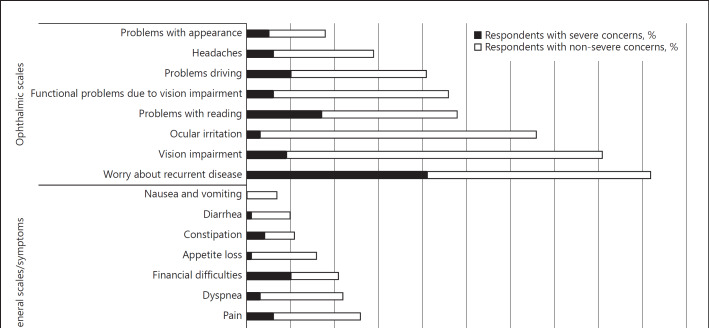

Figure 1 and Table 2 present the reliability analyses and composite scales for general and ophthalmic QOL in the present cohort. Generally, the global health status and functional and symptoms scales all showed good internal consistency, with Cronbach α >0.7 (median 0.85). However, several scales yielded inadequate consistency, including those for cognitive functioning, nausea and vomiting, and problems with appearance. Severe concern about global health was reported by 10% of the cohort. Functional impairment in QOL was reported by <10% of the cohort. Worry about recurrent disease was a severe concern among 41% of respondents, with 92% reporting this. Vision impairment and ocular irritation were also common and reported by 81 and 66% of respondents, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Fraction of patients experiencing severe and non-severe concerns about quality of life across general, functional, and ophthalmic scales.

Factors Associated with QOL

Table 4 presents the results of the multivariable stepwise regression analysis investigating the association of QOL and various demographic, ophthalmic, and tumor-related variables. While many of the variables demonstrated a statistically significant (p < 0.05) association with QOL in the analysis, few of the associations were strong (R2 ≥0.5) [20].

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis of demographic, ophthalmic, and tumor factors associated with quality of life

| Demographic (p value, R2) | Ophthalmic (p value, R2) | Tumor (p value, R2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global health status | PS (<0.01, 0.14) | VA eye with melanoma (<0.01, 0.21) | |

| Functional scales | |||

| Physical functioning | PS (<0.01, 0.25) age (<0.01, 0.39) comorbidity (<0.01, 0.45) sex (0.03, 0.47) |

||

| Role functioning | PS (<0.01, 0.22) comorbidity (0.02, 0.32) sex (0.01, 0.37) |

VA eye with melanoma (<0.01, 0.28) | anterior border (0.03, 0.40) |

| Emotional functioning | comorbidity (0.03, 0.05) sex (<0.01, 0.12) |

||

| Cognitive functioning | PS (<0.01, 0.18) children (0.02, 0.23) |

||

| Social functioning | PS (<0.01, 0.08) | VA eye with melanoma (0.04, 0.12) best VA (0.01, 0.18) | |

| Symptom scales/items | |||

| Fatigue | PS (<0.01, 0.12) age (0.01, 0.18) |

||

| Nausea and vomiting | PS (0.02, 0.06) | ||

| Pain | comorbidity (<0.01, 0.19) | ||

| PS (<0.01, 0.27) | |||

| Dyspnea | age (<0.01, 0.07) | ||

| Insomnia | PS (0.04, 0.05) | posterior border (0.04, 0.09) | |

| Appetite loss | PS (0.02, 0.05) | ||

| Constipation | PS (<0.01, 0.26) age (0.01, 0.31) |

||

| Diarrhea | children (<0.01, 0.12) ethnicity (<0.01, 0.19) |

IOP eye without melanoma (0.01, 0.24) | |

| Financial difficulties | |||

| Ocular irritation | ethnicity (<0.01, 0.08) | retinal detachment (0.04, 0.21) | |

| marriage (<0.01, 0.17) | |||

| Vision impairment | VA eye with melanoma (<0.01, 0.28) | extraocular extension (0.03, 0.50) | |

| VA best eye (<0.01, 0.42) | |||

| IOP eye with melanoma (0.03, 0.46) | |||

| Headaches | |||

| Worry about recurrent disease | |||

| Problems driving | marriage (0.03, 0.42) ethnicity (0.04, 0.46) |

VA eye with melanoma (<0.01, 0.34) | anterior border (0.02, 0.38) |

| Problems with appearance | VA eye with melanoma (<0.01, 0.08) | ||

| Functional problems due to vision impairment | PS (<0.01, 0.40) marriage (0.03, 0.44) ethnicity (0.04, 0.46) |

VA eye with melanoma (<0.01, 0.30) | |

| Problems with reading | VA eye with melanoma (<0.01, 0.21) retinal detachment (<0.01, 0.28) | extraocular extension (0.02, 0.32) | |

| QOL, quality of life; PS, performance status; VA, visual acuity; IOP, intraocular pressure. | |||

| R2 = 0.01–0.19 | |||

| 0.20–0.39 | |||

| 0.40–0.49 | |||

| 0.50 | |||

Among the demographic variables, performance status was associated with global health as well as with many of the functional and symptom scales and items. This parameter reflects a clinician's assessment of how a disease influences a patient's daily living activities, and therefore this association was expected. Advanced age was associated with inferior physical functioning as well as several symptoms, including fatigue and dyspnea. The presence of comorbidities was associated with inferior physical, role, and emotional functioning as well as pain. Male sex was associated with superior physical, role, and emotional functioning. Being single (vs. married) was associated with several ophthalmic symptoms, including ocular irritation, problems when driving, and functional problems from vision impairment.

Visual acuity in the eye with melanoma was significantly associated with several QOL parameters, including global health, role and social functioning, vision impairment, problems driving and reading, problems with appearance, and functional problems due to vision impairment. The best visual acuity (from either eye) was associated with social functioning. Intraocular pressure was associated with vision impairment as well as diarrhea. Finally, the presence of retinal detachment was associated with ocular irritation and problems with reading.

Several tumor variables were associated with QOL. Extraocular extension was strongly associated with vision impairment, and less strongly associated with problems reading. More posteriorly located tumors were associated with inferior role functioning, insomnia, and problems driving.

Among the functional scales, superior physical functioning was most strongly associated with the presence of less severe comorbidities as well as male sex. Greater vision impairment was associated with higher intraocular pressure as well as extrascleral extension of the tumor. Finally, greater problems with driving and functional problems due to vision impairment were associated with Hispanic ethnicity.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the QOL concerns of UM patients after initial diagnosis and prior to radiotherapy, by using 2 psychometric tools designed specifically for this patient population. The results indicate that the QOL of approximately half of UM patients are affected by severe worry about cancer recurrence after initial diagnosis. Moreover, ocular irritation and vision impairment are common ophthalmic QOL concerns present prior to the initiation of any treatment. Finally, this analysis suggests that extraocular extension by the tumor is most strongly associated with vision impairment, and this should be carefully considered by clinicians as a factor associated with compromised QOL. These results are consistent with other analyses suggesting that strategies to identify and mitigate anxiety and vision impairment may be appropriate at the time of initial diagnosis [21], and that the EORTC instruments may be suitable tools to identify patients who might benefit from intervention.

Several previous studies have used the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-OPT30 to investigate QOL in UM patients. However, only 1 study on 69 patients with UM at a single center in France used these instruments to investigate the QOL of patients at diagnosis and before commencement of treatment. Mean global health, functional and symptom scale scores on the QLQ-C30 were remarkably similar to our observations: for example, scores of 68.8 and 76.1, 89.7 and 91.5, 82.4 and 90.4, 75.4 and 78.1, 89.6 and 87.8, 93.7 and 90.6, for global health, physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social functioning scales, between the French cohort and our cohort, respectively. Greater differences between the cohorts were observed using the QLQ-OPT30, with mean scores of 59.8 and 7.7, 32.5 and 20.2, 23.7 and 10.9, 28.6 and 16.9 for problems with appearance, vision impairment, ocular irritation, and problems driving, between the French cohort and ours, respectively. In the French cohort and ours, worry about recurrence was common, with mean scale scores of 41.3 and 47.1, respectively. The consistency of these data in 2 independent cohorts of patients with UM suggest that the EORTC instruments provide a valid method to assess QOL in this patient population.

Most investigations in UM patients using the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-OPT30 have characterized QOL after treatment. Over 1,500 UM patients treated at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital, Liverpool, UK, were assessed using these instruments ≥6 months after treatment. The investigators concluded that QOL after enucleation was worse than after radiotherapy, but speculated that this may have been in the older group of patients with more advanced disease at presentation who were preferentially treated with enucleation. Based on these results, we anticipated inferior QOL in patients with more advanced tumors after initial diagnosis. We did not find this association but did note that features of locally advanced tumors such as extraocular extension were associated with a poorer QOL after diagnosis. At the Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem, Israel, approximately 300 patients with UM underwent evaluation with the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-OPT30 at ≥2 weeks after treatment. Their observations corroborate ours: that global QOL in this patient population is good, but that worry about future health after diagnosis is not uncommon.

While the multivariable analysis of factors associated with QOL demonstrated several statistically significant associations between demographic, ophthalmic, and tumor factors and QOL, none of the associations were large. We suspect that the observed broad variation in responses was primarily responsible for the lack of strong associations, demonstrated by large standard deviations in the raw data (Table 1). Moreover, some characteristics were present in ≤5% of the cohort and associations between these rare variables (non-White race, Hispanic ethnicity, performance status <70, visual acuity ≤20/200, intraocular pressure >21 mm Hg, isolated ciliary body and iris tumors, placoid tumors, extrascleral extension, and AJCC stage group IV) and QOL are difficult to interpret (Table 3). While refinements of these QOL instruments might help avoid this problem, it should be noted that the SDs we observed were entirely consistent with data reported by investigators from Liverpool in a cohort of >1,500 patients, suggesting that the sample size was not the primary cause for variability in response.

Interventional strategies to mitigate the QOL concerns of patients with UM deserve further study, as there are currently limited data to support this approach [21]. A randomized controlled trial of 68 patients with cutaneous melanoma provided evidence that this approach may be worthwhile. The patients randomized to participate in a 6-week structured group intervention soon after initial diagnosis and therapy demonstrated enhanced effective coping and reductions in affective stress. Notably, the study also found an association of the intervention with a reduced risk of melanoma recurrence and death. In attempting to link the intervention to physiologic effects, the authors observed associations between affective measures and immune cell changes [22]. Identifying distressed UM patients for services providing individual or group support to patients, family or caregivers, could prove similarly effective and may warrant further study.

There are potential limitations to this study. First, the study sample was limited to patients after initial diagnosis of UM amenable to radiotherapy. This may not fully encompass the spectrum of UM patients, a fraction of which present with a tumor that does not require treatment or is not amenable to radiotherapy. Nevertheless, at our center, the majority of UM patients that require treatment undergo radiotherapy, and therefore this sample is representative of the majority of patients encountered in practice. Second, the assessment of QOL at a single point in time immediately after evaluation by an ophthalmic oncologist and prior to treatment may not capture the full effect that a diagnosis of UM can have on QOL over months and years. It is possible that during evaluation and soon after treatment, the QOL of a patient may change rapidly. However, for logistic reasons, repeated QOL assessments can prove taxing for the patient, as previously reported [13], and were therefore carried out at a single point in time during initial evaluation. Finally, our cohort represents the QOL of patients at a single cancer center. There may be variation in the patient experience at different centers which may influence QOL. For this reason, pooling of QOL data for analysis may help us to better understand the care delivery factors which are associated with QOL.

In conclusion, we examined QOL concerns in a cohort of UM patients in the USA using instruments designed specifically for this patient population. We found that severe worry about melanoma recurrence was common and present in approximately half of patients, and that ocular irritation and vision impairment may be present before any treatment. Finally, we noted that demographic, ophthalmic, and tumor characteristics may be independently associated with QOL, although these associations were not strong. These results suggest that after a diagnosis of UM, it is possible to detect issues that compromise QOL. Clinicians should be aware of these concerns and further develop strategies to mitigate these factors.

Statement of Ethics

The study protocol has been approved by the research institute's committee on human research.

Disclosure Statement

C.A.B. has participated as an advisory board member for Pfizer and Novartis, and his institution receives research funding from Amgen and Merck. A.N.S. has participated as an advisory board member for Bristol Myers Squibb, Castle Biosciences and Immunocore, and his institution receives research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Astra Zeneca, and Immunocore.

Funding Sources

This study was supported by a Cancer Center support grant to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, P30-CA008748 (PI: Craig Thompson) and the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center College of Medicine Summer Alumni Research Fellowship (the latter to A.K.).

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception or design of the work or interpretation of data, AND drafted or revised it critically for important intellectual content, AND, approved the final version to be published, AND, agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the patients and caregivers who participated in this study.

References

- 1.Jampol LM, Moy CS, Murray TG, Reynolds SM, Albert DM, Schachat AP, et al. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group (COMS Group) The COMS randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma: IV. Local treatment failure and enucleation in the first 5 years after brachytherapy. COMS report no. 19. Ophthalmology. 2002 Dec;109((12)):2197–206. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group The COMS randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma: V. Twelve-year mortality rates and prognostic factors: COMS report No. 28. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006 Dec;124((12)):1684–93. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.12.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chmielowska K, Tomaszewski KA, Pogrzebielski A, Brandberg Y, Romanowska-Dixon B. Translation and validation of the Polish version of the EORTC QLQ-OPT30 module for the assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with uveal melanoma. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2013 Jan;22((1)):88–96. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chabert S, Velikay-Parel M, Zehetmayer M. Influence of uveal melanoma therapy on patients' quality of life: a psychological study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2004 Feb;82((1)):25–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0420.2003.0210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanco-Rivera C, Capeáns-Tomé C, Otero-Cepeda XL. [Quality of life in patients with choroidal melanoma] Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2008 May;83((5)):301–6. doi: 10.4321/s0365-66912008000500005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandberg Y, Damato B, Kivelä T, Kock E, Seregard S, Force EO, et al. EORTC Ophthalmic Oncology Task Force. EORTC Quality of Life Group The EORTC ophthalmic oncology quality of life questionnaire module (EORTC QLQ-OPT30). Development and pre-testing (Phase I-III) Eye (Lond) 2004 Mar;18((3)):283–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruickshanks KJ, Fryback DG, Nondahl DM, Robinson N, Keesey U, Dalton DS, et al. Treatment choice and quality of life in patients with choroidal melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999 Apr;117((4)):461–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.4.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damato B, Hope-Stone L, Cooper B, Brown SL, Salmon P, Heimann H, et al. Patient-reported Outcomes and Quality of Life After Treatment of Choroidal Melanoma: A Comparison of Enucleation Versus Radiotherapy in 1596 Patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018 Sep;193:230–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foss AJ, Lamping DL, Schroter S, Hungerford J. Development and validation of a patient based measure of outcome in ocular melanoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000 Apr;84((4)):347–51. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.4.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frenkel S, Rosenne H, Briscoe D, Hendler K, Bereket R, Molcho M, et al. Long-term uveal melanoma survivors: measuring their quality of life. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018 Jun;96((4)):e421–6. doi: 10.1111/aos.13655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hope-Stone L, Brown SL, Heimann H, Damato B, Salmon P. Two-year patient-reported outcomes following treatment of uveal melanoma. Eye (Lond) 2016 Dec;30((12)):1598–605. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klingenstein A, Fürweger C, Mühlhofer AK, Leicht SF, Schaller UC, Muacevic A, et al. Quality of life in the follow-up of uveal melanoma patients after enucleation in comparison to CyberKnife treatment. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016 May;254((5)):1005–12. doi: 10.1007/s00417-015-3216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kopp BC, Crump RT, Weis E. The use of semistructured interviews to assess quality of life impacts for patients with uveal melanoma. Can J Ophthalmol. 2017 Apr;52((2)):181–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melia BM, Moy CS, McCaffrey L. Quality of life in patients with choroidal melanoma: a pilot study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1999 Mar;6((1)):19–28. doi: 10.1076/opep.6.1.19.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandberg Y, Kock E, Oskar K, af Trampe E, Seregard S. Psychological reactions and quality of life in patients with posterior uveal melanoma treated with ruthenium plaque therapy or enucleation: a one year follow-up study. Eye (Lond) 2000 Dec;14((Pt 6)):839–46. doi: 10.1038/eye.2000.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melia M, Moy CS, Reynolds SM, Hayman JA, Murray TG, Hovland KR, et al. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study-Quality of Life Study Group Quality of life after iodine 125 brachytherapy vs enucleation for choroidal melanoma: 5-year results from the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study: COMS QOLS Report No. 3. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006 Feb;124((2)):226–38. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suchocka-Capuano A, Brédart A, Dolbeault S, Rouic LL, Lévy-Gabriel C, Desjardins L, et al. [Quality of life and psychological state in patients with choroidal melanoma: longitudinal study] Bull Cancer. 2011 Feb;98((2)):97–107. doi: 10.1684/bdc.2011.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reimer J, Voigtlaender-Fleiss A, Karow A, Bornfeld N, Esser J, Helga Franke G. The impact of diagnosis and plaque radiotherapy treatment of malignant choroidal melanoma on patients' quality of life. Psychooncology. 2006 Dec;15((12)):1077–85. doi: 10.1002/pon.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kline P. The handbook of psychological testing. 2nd ed. London; New York: Routledge: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992 Jul;112((1)):155–9. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williamson TJ, Jorge-Miller A, McCannel TA, Beran TM, Stanton AL. Sociodemographic, Medical, and Psychosocial Factors Associated With Supportive Care Needs in Adults Diagnosed With Uveal Melanoma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018 Apr;136((4)):356–63. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fawzy FI, Canada AL, Fawzy NW. Malignant melanoma: effects of a brief, structured psychiatric intervention on survival and recurrence at 10-year follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003 Jan;60((1)):100–3. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]