Abstract

Ultrafast lasers are becoming increasingly widespread in science and industry alike. Fiber-based ultrafast laser sources are especially attractive because of their compactness, alignment-free setups, and potentially low cost. However, confining short pulses within a fiber core leads to high intensities, which drives a host of nonlinear effects. While these phenomena and their interactions greatly complicate the design of such systems, they can also provide opportunities for engineering new capabilities. Here, we report a new fiber amplification regime distinguished by the use of a dynamically evolving gain spectrum as a degree of freedom: as a pulse experiences nonlinear spectral broadening, absorption and amplification actively reshape both the pulse and the gain spectrum itself. The dynamic co-evolution of the field and excited-state populations supports pulses that can broaden spectrally by almost two orders of magnitude and well beyond the gain bandwidth, while remaining cleanly compressible to their sub-50-fs transform limit. Theory and experiments provide evidence that a nonlinear attractor underlies the management of the nonlinearity by the gain. Further research into these mutual, pulse-inversion propagation dynamics may address open scientific questions and pave the way toward simple, compact fiber sources that produce high-energy, sub-30-fs pulses.

1. INTRODUCTION

High-peak-intensity ultrafast fiber lasers are desirable for industrial, defense, and scientific applications [1–3]. Fiber lasers possess many advantages over their solid-state counterparts including accumulation of large nonlinear effects, which degrade the pulse quality. High-energy sources are often based on chirped-pulse amplification (CPA) [4], in which the pulse from an oscillator is stretched, amplified, and subsequently compressed. Stretching reduces the peak intensity and, in turn, the strength of nonlinear effects such as self-phase modulation (SPM) and stimulated Raman scattering (SRS). In a typical fiber CPA system, the pulse duration is limited to ~200 fs by gain narrowing [1] and residual dispersion mismatch between the stretcher and compressor. Although the dispersion mismatch can be mitigated to some degree by SPM-induced nonlinear phase [5], gain narrowing remains an ongoing and major challenge. While 200-fs pulses are suitable for some applications, others, such as high harmonic generation, benefit from shorter pulse durations [6]. Shorter pulses can be obtained by a subsequent stage of nonlinear pulse compression, which increases the complexity of the system and decreases the overall efficiency [7]. In contrast to CPA, there exist techniques based on nonlinear pulse propagation that can be used to achieve sub-100-fs pulse durations. These include direct amplification [8] and pre-chirp management [9,10], as well as amplifiers designed to support self-similar pulse evolution [11–13]. While such approaches can yield sub-100-fs pulses [9,14,15], they suffer from their own set of limitations. Similariton amplifiers benefit from a nonlinear attractor [16] that is indifferent to many of the seed characteristics, but at higher energies their spectra overflow the gain bandwidth, degrading the compressed pulse quality [17]. Nonlinear amplifiers using pre-chirp management can extend this limit and reach energies as high as the microjoule level and durations as short as 24 fs [15]; however, achieving optimal performance often requires a carefully chosen seed pulse, which hampers energy scaling and increases the complexity of the design.

Here, we describe and experimentally demonstrate a new regime of fiber amplification that addresses two main challenges of ultrafast fiber lasers: (1) management of the high nonlinear phase shifts encountered in stretcher-less amplification systems and (2) generation of bandwidths much broader than the gain spectrum that can be compressed to clean, sub-100-fs pulses. In this regime, the pulse and gain spectra evolve and reshape one other in tandem, so we refer to this as amplification with gain-managed nonlinearity (GMN). The intentional use of co-evolving gain to control pulse evolution is rare. In contrast to previously investigated amplifiers where doping was used as a degree of freedom to reduce the nonlinearity and heat load [18,19], we engineer the evolution of the gain spectrum to deliberately take advantage of nonlinear effects. In this regime, an accumulation of nonlinear phase on the order of ~200π (which corresponds to 70-fold spectral broadening) can be accommodated while still generating clean compressed pulses. Experimentally, we demonstrate the GMN regime in ytterbium-doped fiber and obtain broadband amplified pulses that can be compressed to ~40 fs durations. Numerical simulations and experimental results suggest that the pulse evolution in the gain medium is driven by a nonlinear attractor, which has interesting scientific implications and may simplify device design.

2. RESULTS

A. Numerical Simulations

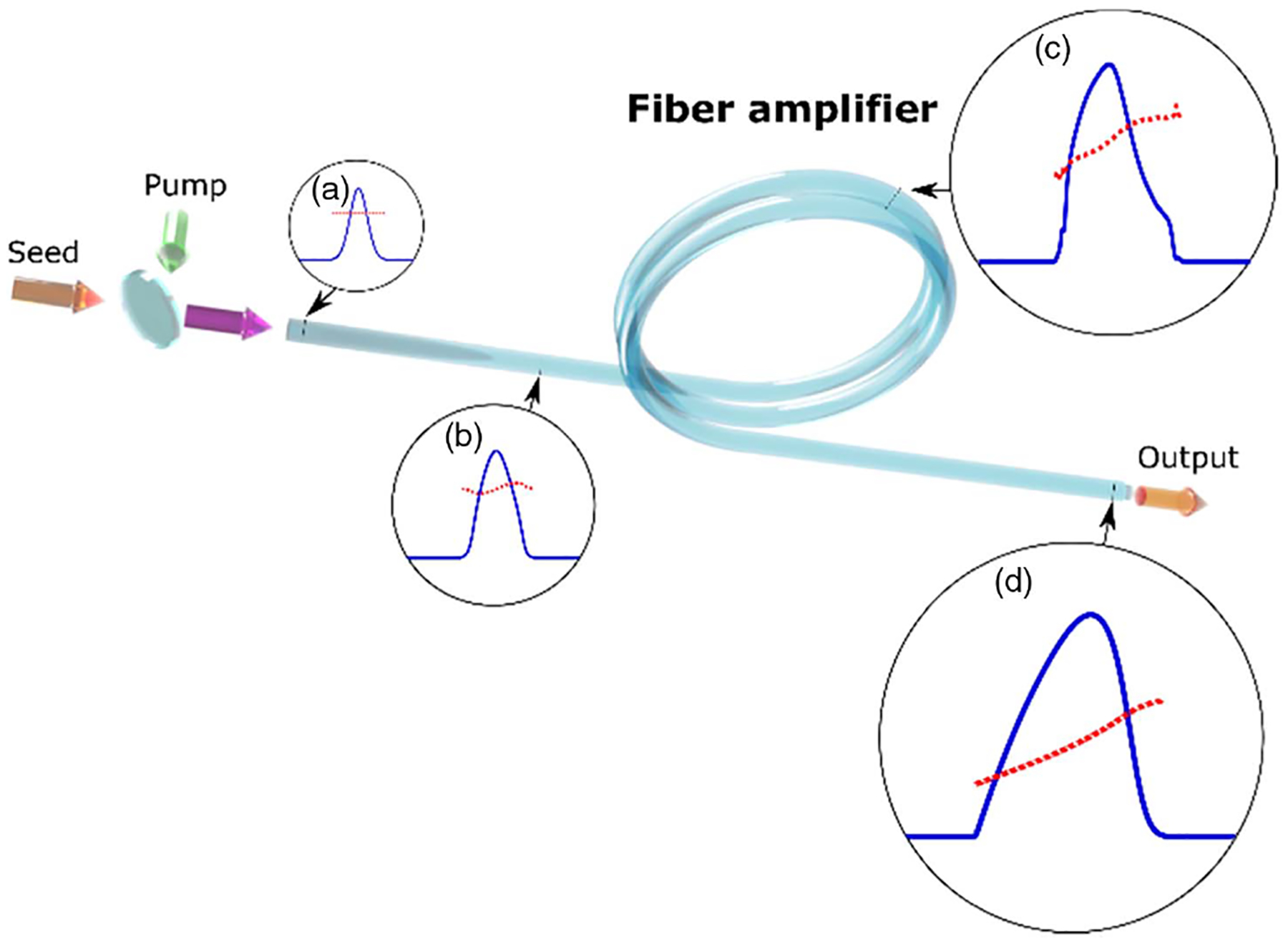

We begin by illustrating the GMN amplification regime numerically using a simple example. Figure 1 illustrates the simulated pulse evolution in a typical, highly doped, ytterbium fiber amplifier. A 0.5-nJ, 0.8-ps Gaussian pulse at 1028 nm is launched into a double-clad Yb-doped fiber amplifier with a 6-μm core diameter, which is co-pumped at 976 nm. The numerical model includes second- and third-order dispersive effects, along with SPM, self-steepening, Raman scattering, and the gain calculated by solving the population inversion rate equations simultaneously with the pulse evolution [20,21]. The pulse evolution initially follows a well-known trajectory: dispersive and nonlinear effects are both prevalent, and the pulse quickly evolves toward a self-similar pulse or similariton [12,13] [Fig. 1(b)]. As the pulse’s energy and bandwidth increase, gain-shaping begins to impede the similariton’s growth, leading to the expected nonlinear pulse distortions and the loss of self-similar propagation [17,22] [Fig. 1(c)]. This point is traditionally taken to be the limit of self-similar amplification, with the result that such systems rarely reach useful energies for high-performance applications. However, if the pulse evolution is allowed to continue, a new regime emerges. As the inversion decays away, the pulse shifts towards longer wavelengths and continues broadening in both the spectral and temporal domains. The pulse energy increases and the pulse evolves to an asymmetric temporal profile [Fig. 1(d)]. Perhaps most surprisingly, the new pulse develops a monotonic chirp that can be compensated with a grating pair (as will be shown below).

Fig. 1.

Simulated example of GMN amplification regime. The temporal intensity (solid blue line) and instantaneous frequency (dotted red line) are plotted for (a) the seed pulse, (b) the self-similar pulse, (c) the pulse beyond the self-similar regime, and (d) the pulse in the GMN regime.

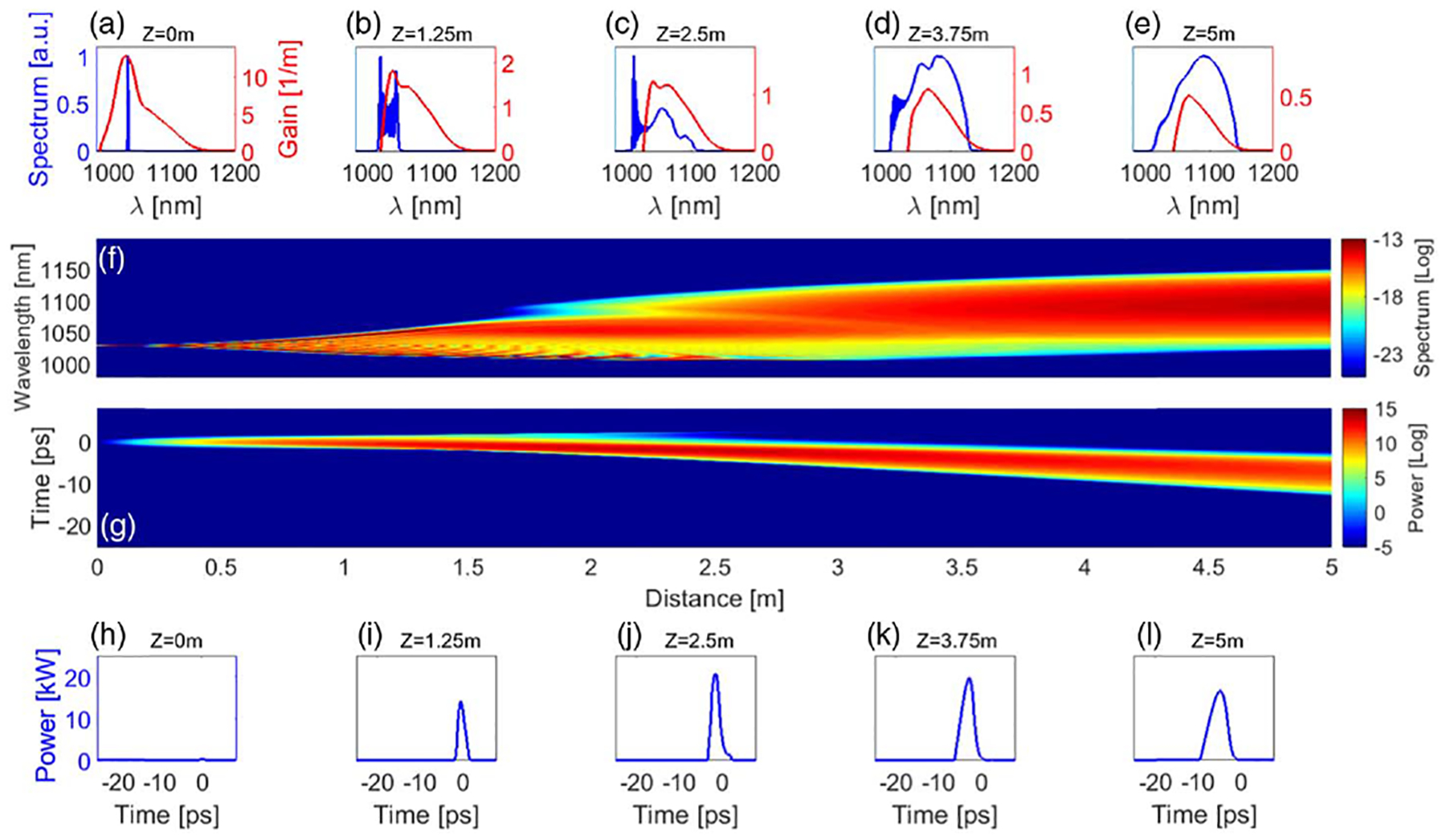

This new regime that unexpectedly emerges beyond self-similar amplification is interesting from the standpoints of both nonlinear-wave physics and applications. To understand its origins, we perform additional, more detailed, simulations. We find that modeling the true gain calculated from the rate equations is of crucial importance, as the quasi-three-level nature of Yb-doped fiber leads to the gain spectrum changing dynamically as different components of the pump and signal waves are absorbed and reemitted. This leads to a longitudinally evolving gain spectrum and an intertwining of the roles of nonlinearity and gain-shaping, with the end result that the nonlinear phase is managed and a compressible frequency chirp is maintained. The main features of the GMN amplification regime are illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3. We find that the mutual interaction of the signal and gain can be enhanced in long, highly doped fibers, and when the seed wavelength is chosen to be close to the transition between absorption and gain in the fiber. We therefore keep the same 1028-nm seed wavelength as before, but increase the transform-limited duration to 2 ps in order to explore the use of different seed pulses. As above, a double-clad Yb-doped fiber amplifier with a 6-μm core diameter that is co-pumped at 976 nm is assumed. Initially, the pulse evolution is dominated by SPM [Figs. 2(a) and 2(b)]. Remarkably, after ~2 m, the pulse begins evolving toward a smooth, asymmetric temporal shape instead of experiencing the expected wave-breaking distortions [23,24]. The longitudinal evolution of the gain spectrum is shown in Figs. 2(a)–2(e) with a solid red curve. The GMN regime is achieved when nonlinear spectral broadening balances gain-shaping. This balance manifests as absorption of the blue part of the spectrum and amplification of the red part [Figs. 2(c)–2(e), 1(j)–2, and 3(a)]. This deliberate use of both gain and loss during pulse amplification is a crucial aspect of the GMN regime, despite running counter to conventional amplifier design rules. Furthermore, unlike every other established amplification regime, the peak power of the pulse does not increase monotonically with propagation through the amplifier. Instead, it reaches a maximum at ~2 m and decreases thereafter [Figs. 2(h)–2(l) and 3(b)]. This nonmonotonic behavior is due to the dynamic balance between gain and dispersion, as can be seen in Figs. 3(b) and 3(c). During the initial stage of evolution, where the pulse is evolving toward the parabolic attractor, the peak power grows as expected due to the nearly exponential, broadband (relative to the pulse) gain, and the pulse bandwidth increases. The effects of dispersion increase due to the nonlinearly accruing bandwidth, while the rate of amplification decreases as more of the pump is absorbed; after ~2 m of propagation, dispersive temporal broadening overcomes the gain and causes the peak power to subsequently decrease. The pulse energy continues to increase monotonically, aided by the increasing temporal duration, while the pulse maintains its time-domain intensity profile.

Fig. 2.

Simulated pulse evolution in Yb-doped fiber. The top two rows [(a)–(f)] show the spectral evolution of the amplified pulse (blue) and saturating gain spectrum (red), while the bottom two rows [(g)–(l)] show the pulse’s temporal evolution.

Fig. 3.

Pulse and gain evolution in a GMN amplifier. (a) Longitudinal evolution of the gain. Black dashed curves mark the pulse’s spectrum (central wavelength ± the root-mean-square bandwidth). (b) Peak power (blue) and pulse energy (red) versus propagation distance. (c) Bandwidth (blue) and chirped duration (red) of the pulse versus propagation distance.

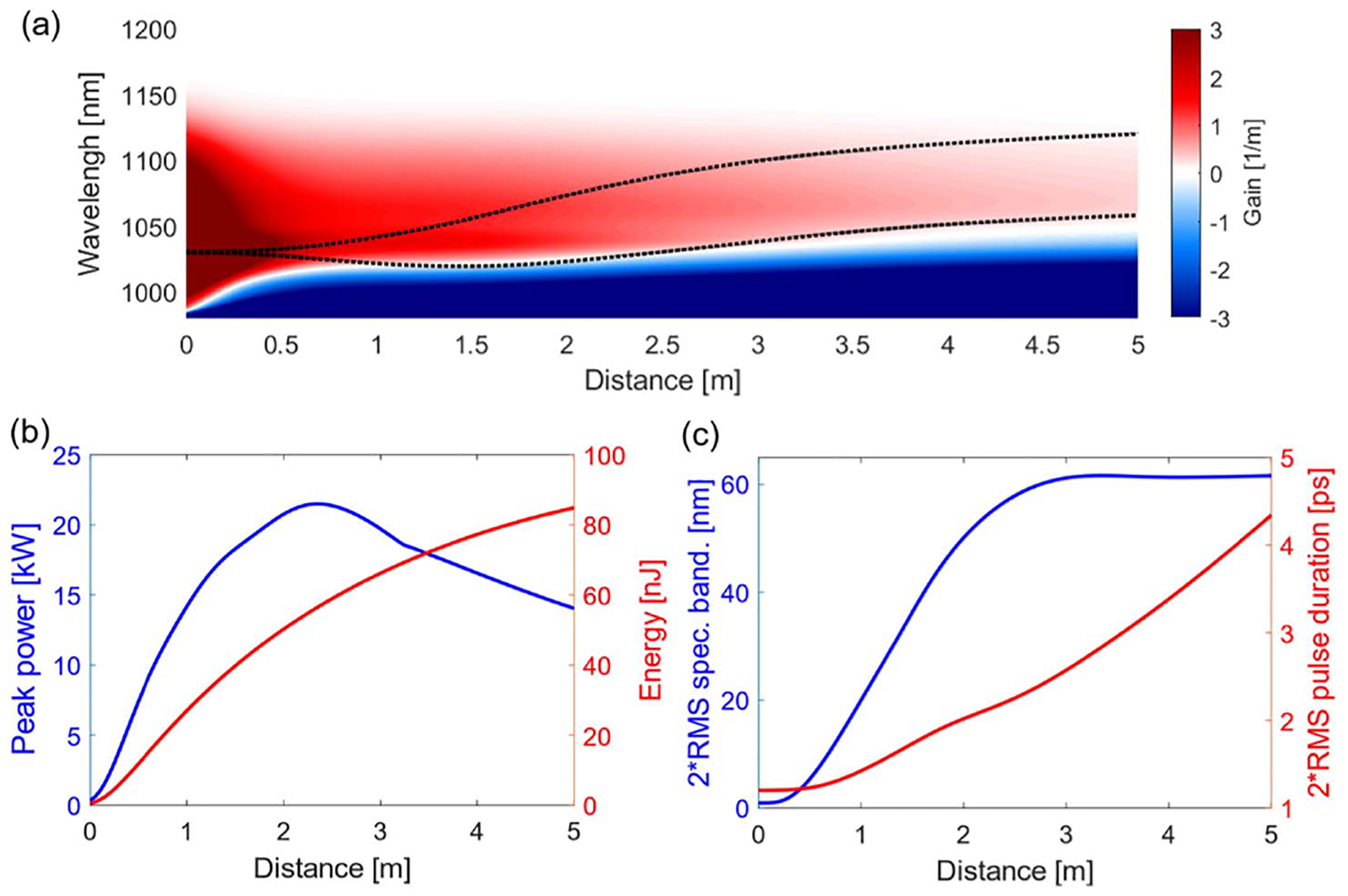

Close comparison of the spectral evolution of the pulse and gain helps to understand the GMN regime. The initial spectral broadening is arrested when the blue side of the spectrum encounters the absorption near 1020 nm [Figs. 3(a)]. This absorption feature and the gain window both shift to the red with continuing evolution, so the blue side of the pulse spectrum is limited while its red side continues to broaden unhindered. As the peak power and the net gain start to decay, the growth of the pulse spectral bandwidth saturates, hemmed in by residual absorption on the blue side and vanishing gain on the red side. This is the origin of the asymmetric, steady-state pulse that emerges at the output of the amplifier [Figs. 2(f) and 4(a)]. Surprisingly, following this complicated and dynamic mixing of spectral components, the pulse [Fig. 4(a)] can be easily compressed to near the transform limit [Fig. 4(b)]. The deviation from a linear chirp is readily accommodated by the standard design of a grating compressor [25]. Thus, despite the extremely nonlinear and broadband pulse evolution, a simple grating compressor suffices to produce a high-quality, nearly transform-limited pulse. The cleanliness of this compression despite 120π of nonlinear phase accumulation is a hallmark of similariton evolution; however, the pulse has clearly developed beyond the similariton regime in terms of its propagation trajectory, its bandwidth, and its overall performance. The GMN pulse evolution is unchanged when higher-order dispersion and self-steepening are eliminated from the calculations. Thus, it requires only group-velocity dispersion, SPM, and the true gain as calculated from the rate equations.

Fig. 4.

Pulses generated by a GMN amplifier. (a) Chirped output pulse from the example presented in Fig. 2. (b) Compressed pulse (solid blue curve) and transform-limited pulse (red dashed curve). The insets in (a) and (b) show spectrograms of the chirped pulse (gated by 1-ps Gaussian window) and the compressed pulse (gated by 5-fs Gaussian window), respectively.

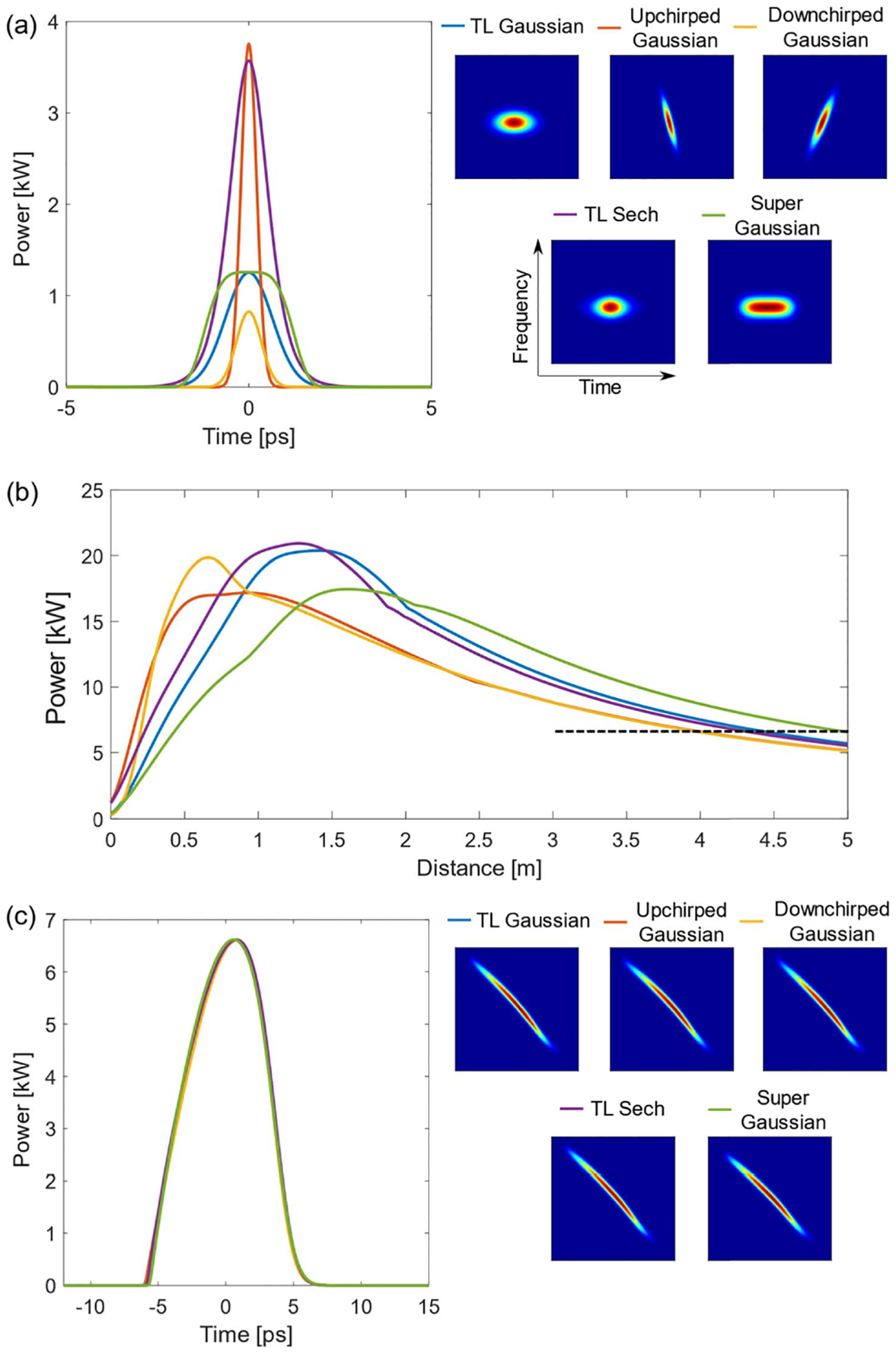

The simulations also provide indications that the final, asymmetric pulse shape is a nonlinear attractor. That is, the pulse evolution in the GMN regime is driven more by nonlinearity and gain-shaping than by the particular parameters of the seed pulse. To demonstrate this, we simulate launching seed pulses that span a range of shapes, energies, durations, chirps, bandwidths, and peak powers [Fig. 5(a)] into a fixed amplifier. The different pulses evolve in a qualitatively similar manner: each passes through an initial, SPM-dominated transient before entering the GMN amplification regime. The transition between these two regimes depends on the seed pulse, and can be approximated based on the peak power, which reaches a maximum near the transition point and subsequently decreases as is characteristic of the GMN regime [Fig. 5(b)]. In particular, although the different pulses evolve at different rates, we can compare them at equivalent points in their evolutions by noting where each crosses a peak power threshold [dashed black line in Fig. 5(b)]. At that point, the pulses are nearly identical [Fig. 5(c)], providing strong evidence that the amplified pulse is a nonlinear attractor.

Fig. 5.

Numerical evidence of the nonlinear attractor. (a) Different seed pulses and their corresponding spectrograms. TL: transform-limited. (b) Evolution of the peak power for each seed. (c) Amplified pulses produced with the different seeds, taken at the same power level [indicated by the dashed black line in (b), arbitrarily chosen to be 6.6 kW].

Scientifically, nonlinear attractors are interesting objects to study due to their fundamental role in nonlinear dynamical systems. To our knowledge, the only other nonlinear attractor in normal-dispersion amplifiers is the similariton [12,13]. The rarity of nonlinear attractors in fiber systems and the similarities between the two regimes make it natural to wonder whether the similariton and GMN regimes might be related. We currently believe that they are not, due to several features that fundamentally distinguish the GMN regime. It is well known that, although similaritons can exist within various homogeneously broadened [12] and saturated [26] gain models, they will distort and become incompressible in the presence of gain-shaping [17,22]. In contrast, the GMN regime can only exist when strong gain-shaping is present, with the effects of both gain and loss included. This is exemplified by the spectrum in Fig. 2, which significantly exceeds the gain bandwidth [red curves in Figs. 2(a)–2(e)] over much of the pulse’s propagation. Furthermore, a similariton is characterized by exponential growth in its energy, duration, peak power, and bandwidth. A pulse in the GMN regime grows only in duration [Fig. 3(c)], while its energy and bandwidth saturate [Figs. 3(b) and 3(c)] and its peak power decreases [Fig. 3(b)]. However, further research into the nature of the GMN regime may reveal connections underlying these two attractors.

B. Experimental Results

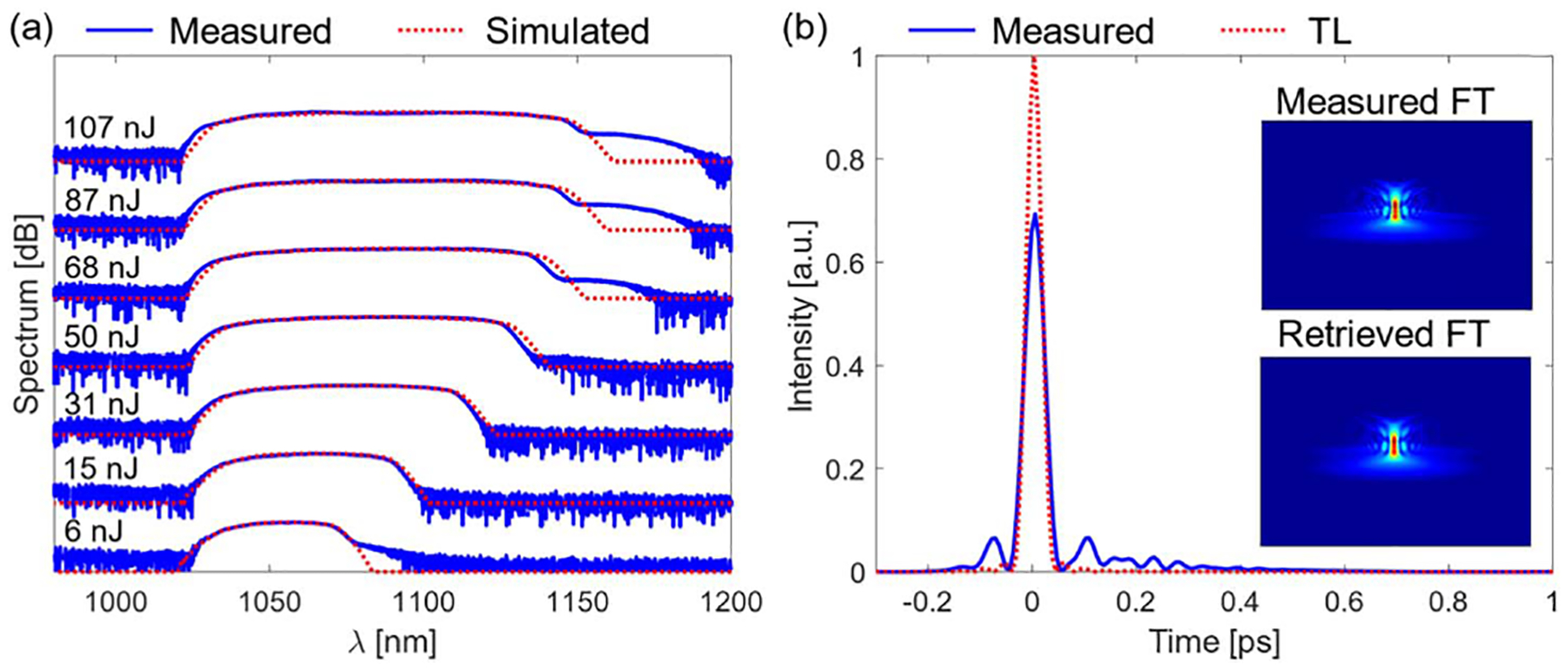

Guided by numerical simulations, we experimentally demonstrate GMN amplification in 5 m of highly doped double-clad Yb fiber with a 5-μm core diameter (Nufern PM-YDF-5/130-VIII), co-pumped by a 976-nm diode. We seed the amplifier with transform-limited 700-fs, 1-nJ pulses generated by spectrally filtering the blue part of the compressed output of an all-normal-dispersion femtosecond fiber laser [27]. The repetition rate of the seed is 12.5 MHz. With increasing pump power, the spectrum broadens substantially, in agreement with simulations [Fig. 6(a)]. The measured bandwidth rapidly grows to extend past 1100 nm, overflowing the bandwidth of Yb-doped gain media. Using a grating compressor, we are able to dechirp the amplified pulses to their transform limit, indicating that the generated bandwidth is coherent rather than originating from shot-noise-seeded Raman scattering. The coherence of the pulses across their full bandwidths is further confirmed using dispersive Fourier transform measurements [28] (not shown), which show that the single-shot pulse spectra are stable and low-noise. For pulse energies of 68 nJ or higher, Raman scattering is observed, but only as a low-intensity spectral shoulder that is clearly distinguishable from the main pulse. At the highest output pulse energy (107 nJ, where the Raman contribution is less than 3% of the pulse energy), the amplified pulses are compressed to 42 fs, near the transform limit [Fig. 6(b)]. We note that 89% of the energy is in the main pulse, and only 11% of the energy is distributed in the uncompressed pedestal. (Quantitative discrepancies between the simulated and experimental Stokes waves are discussed in Fig. S1 of Supplement 1.)

Fig. 6.

Experimental demonstration of a GMN amplifier. (a) Measured (blue solid curve) and simulated (red dashed curve) output spectra for increasing pump power (labeled with the output energies). (b) Compressed (blue solid curve) 107-nJ pulse and transform-limited pulse (red dashed curve). Insets in (b) show measured and retrieved SHG-FROG traces.

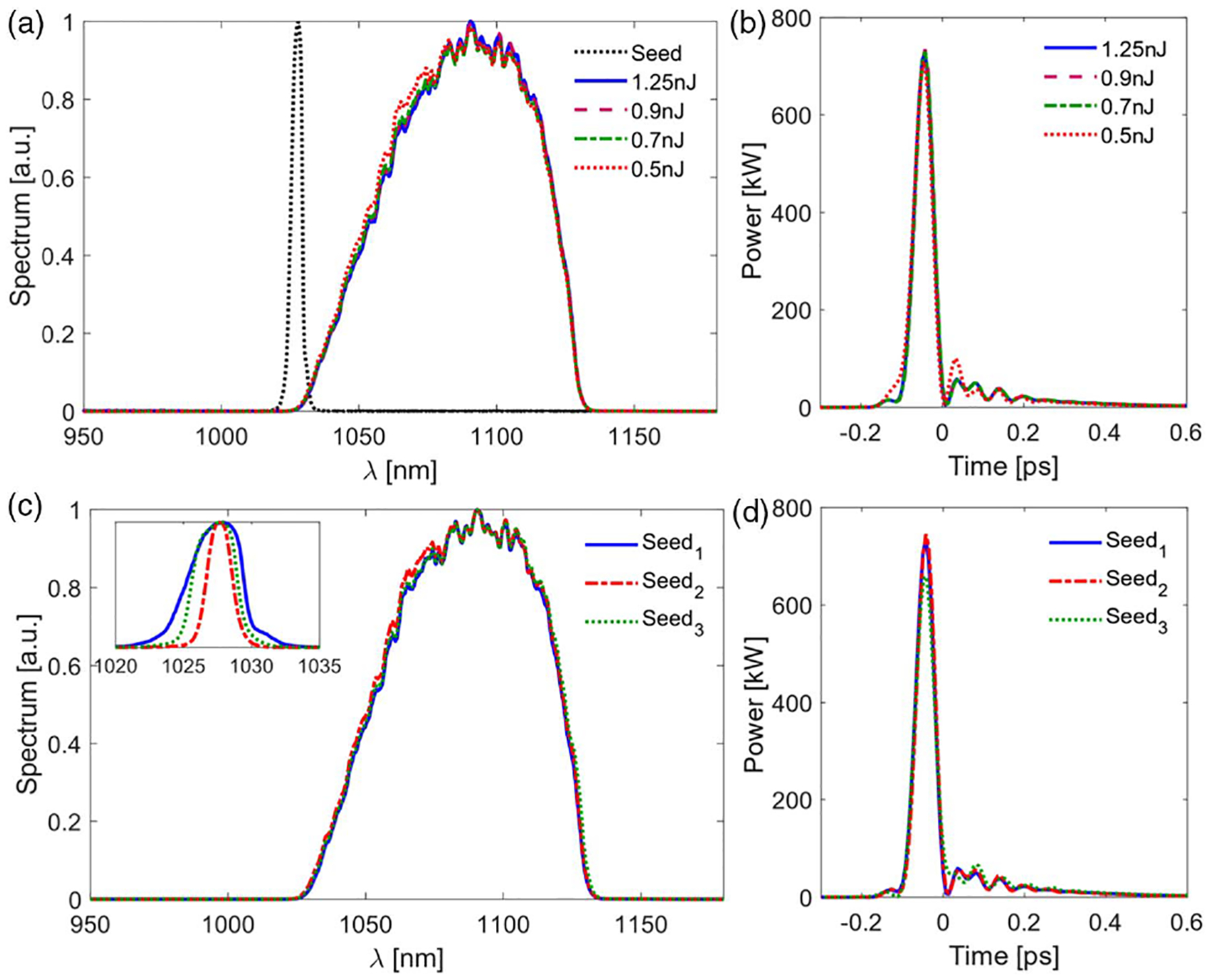

To investigate the numerical prediction that the pulse evolves to a nonlinear attractor, we launch a variety of seed pulses into an amplifier. In one experiment, the seed spectrum and duration are held constant while the energy is varied by nearly a factor of 3 [Figs. 7(a) and 7(b)]; in another, a filter is used to vary the bandwidth of the transform-limited seed (and, thereby, vary its duration) while its energy is held constant at 0.5 nJ [Figs. 7(c) and 7(d)]. With either type of variation, the output spectrum [Figs. 7(a) and 7(c)] and compressed pulse [Figs. 7(b) and 7(d)] remain largely invariant, with no adjustment of the pump power or grating compressor. This stark insensitivity of the output to the seed characteristics is a strong indication that a nonlinear attractor underlies the GMN amplification regime.

Fig. 7.

Experimental evidence of a nonlinear attractor. (a) Output spectra of a GMN amplifier and (b) the corresponding compressed pulses for a constant seed spectrum [black dashed curve in (a)], with the indicated seed pulse energies. (c) Output spectra and pulse shapes of a GMN amplifier seeded with constant seed energies (inset: seed spectra), and (d) corresponding dechirped pulses.

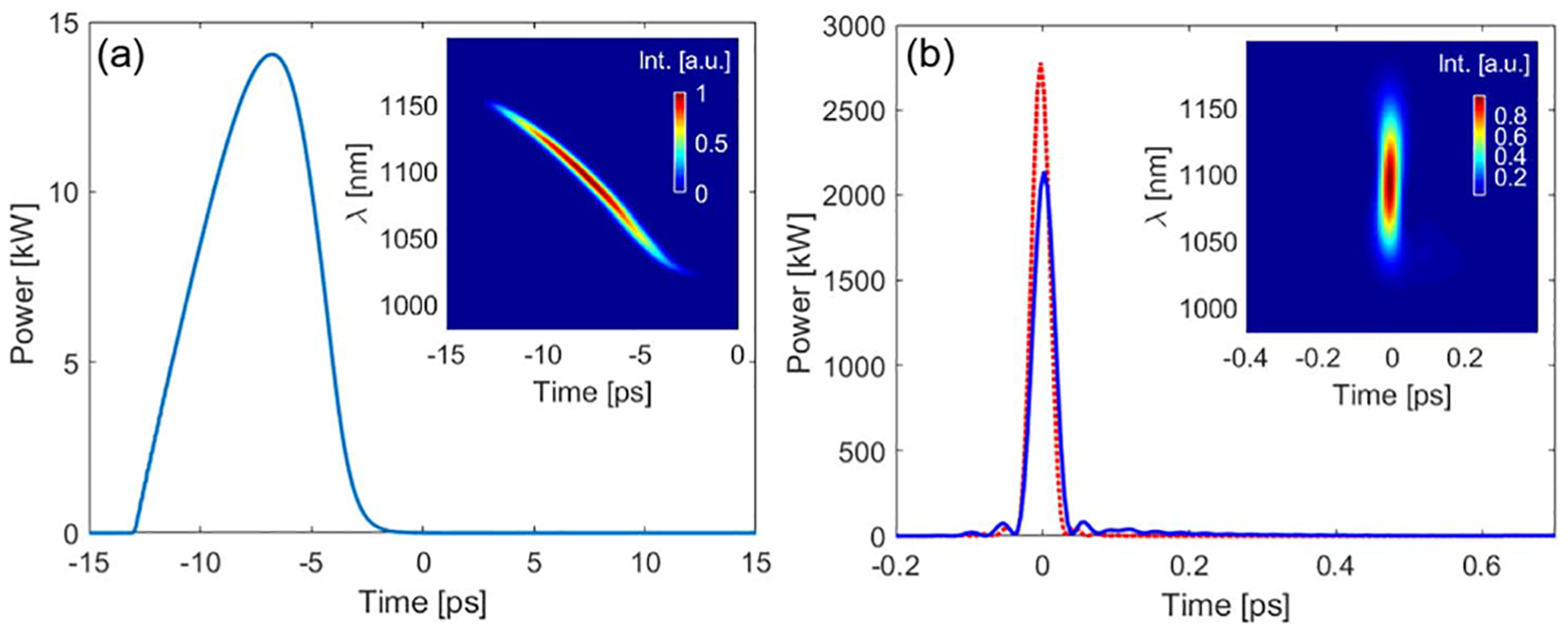

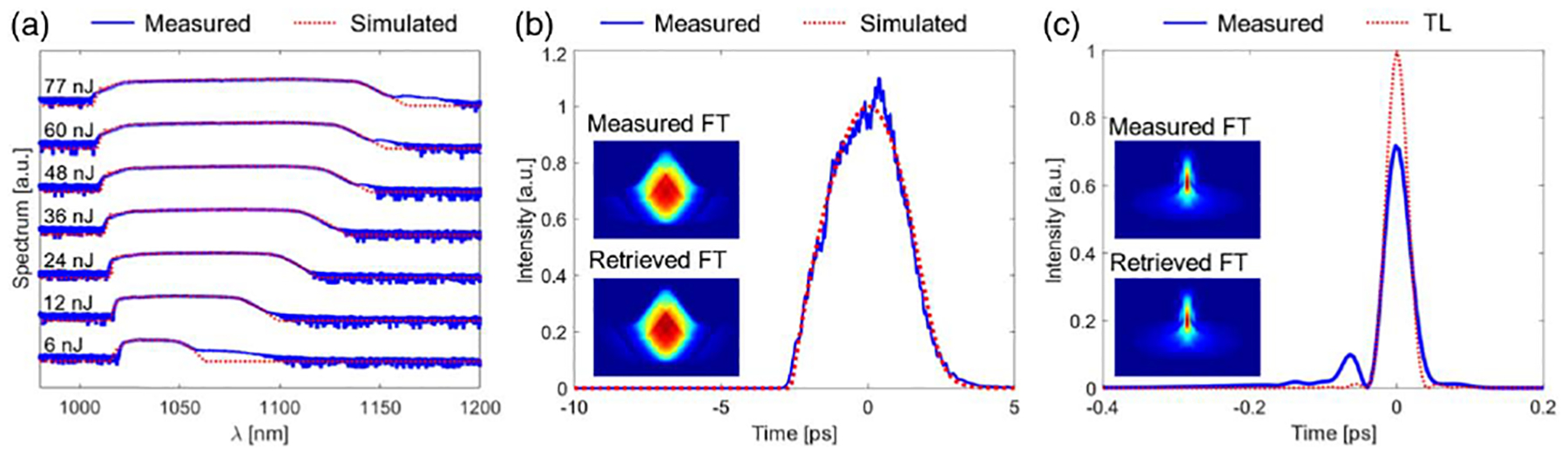

Considering the significance of the attracting pulse shape in the GMN regime, it is important to measure the pulse directly from the amplifier and compare it with simulations. Unfortunately, our frequency-resolved optical gating (FROG) [29] instrument lacks the scanning range to measure the chirped pulse from the amplifier described above. Therefore, we constructed a shorter amplifier, seeded by narrowband transform-limited pulses with an energy of 3 nJ. This yields shorter, lower-energy, less-broadband amplified pulses that can be measured directly with FROG. Simulations of this amplifier exhibit good agreement with the measurements (Fig. 8). We limited the pulse energy to 77 nJ to limit the bandwidth. The measured output pulse exhibits the expected asymmetric temporal shape and good agreement with simulations [Fig. 8(b)], and can be compressed to near the transform limit [Fig. 8(c)].

Fig. 8.

Direct measurement of chirped pulses from a GMN amplifier. (a) Measured (solid blue curve) and simulated (red dashed curve) spectra for increasing pump powers. (b) Measured (blue solid curve) and simulated (red dashed curve) pulse shapes that correspond to the 77-nJ result in (a). (c) Measured compressed pulse (blue solid curve) and calculated transform-limited pulse (red dashed curve).

3. DISCUSSION

In this work, we have presented initial demonstrations of the GMN amplification regime. Several aspects of this work present opportunities for future investigations. Although our focus has been on the nonlinear-wave physics, it should be mentioned that the results obtained here already offer performance advantages over prior approaches. The generation of stable 200-nJ and 40-fs pulses (Fig. S2 in Supplement 1) with ordinary, single-mode fiber is remarkable. Simulations indicate that 300-nJ and 30-fs pulses should be possible with greater pump power. It will also be interesting to investigate pulse energy scaling in the GMN regime to large mode area (LMA) fibers: for double-clad LMA fibers, the rate of pump absorption will affect the longitudinal gain evolution in a non-trivial manner, which may result in scaling relations more complex than simple mode-area scaling. While we have focused on the short pulses obtainable using this approach, filtering the output yields energetic, transform-limited pulses in spectral regions outside conventional gain windows (Fig. S3 in Supplement 1).

The GMN regime exists in systems where a longitudinally varying population inversion gives rise to a changing gain spectrum. While we have focused on Yb-doped fiber as an exemplary case of this regime, other widely used gain media such as Er-, Tm-, and Nd-doped fibers also satisfy this criterion. Thus, the GMN regime should be accessible in other spectral regions, provided that normal dispersion can be obtained. An example of an Er-based GMN amplifier is shown in Supplement 1, Fig. S4. It will also be interesting to look into systems where the gain and loss are artificially arranged. For example, we might envision fiber Bragg gratings written directly into gain fibers [30] being used to manipulate and engineer the evolution of the gain and loss [31,32]. Combinations of different gain media, such as Yb–Er co-doped gain fibers, and/or the simultaneous use of co- and counter-propagating pump fields, could also be employed to further engineer the longitudinal gain evolution.

The possible existence and nature of a nonlinear attractor motivate future work. So far, we have been unable to derive analytical solutions of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation coupled with the population rate equations. We expect that an analytical solution will reveal more properties and provide a better understanding of the GMN amplification regime. As an example of a practical application of the nonlinear attractor, it may be possible to reduce or compensate noise or drift in a source of seed pulses (evidence of this is presented in Fig. S5 in Supplement 1). This would allow even relatively noisy sources, such as harmonically mode-locked oscillators [33], to be used to seed GMN amplifiers. Investigation of the noise properties of GMN amplifiers will be a subject of future work that may open a way for noise reduction in fiber amplifiers. Numerical simulations (Fig. S6 in Supplement 1) show that the GMN regime underlies the pulse evolution in recently developed high-performance fiber oscillators [34,35]. We anticipate that a better understanding of the nature of the nonlinear attractor in the GMN regime will significantly advance the design and optimization of such oscillators.

From the standpoint of performance, it is interesting to consider how GMN-based fiber amplifiers might be scaled to extremely large mode areas. Such fibers exist [36], but it is well known that the existence and population of multiple transverse modes can lead to reductions in the output beam quality [37]. Kerr beam self-cleaning [38] is a recently discovered technique that shows promise as a means of improving the quality of multimode beams, but relies on strong Kerr nonlinearity. The ability of the GMN regime to tolerate similarly high nonlinear phase shifts raises the intriguing possibility of combining these two techniques: one might envision GMN-based fiber amplifiers that can take advantage of huge-core, highly multimode fibers without sacrificing beam quality. If realized, such systems could extend fiber lasers to the 100-MW level while retaining ~30 fs pulse durations, putting them for the first time in direct competition with solid-state CPA systems.

Most broadly, nonlinear Schrödinger equations play an important role in science by explaining a variety of nonlinear phenomena in physics [39,40]. Thus, results presented here may influence advances not only in the field of nonlinear optics but also in areas such as superconductivity, plasma physics, and nonequilibrium statistical mechanics, where many phenomena are governed by nonlinear Schrödinger equations.

4. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we numerically and experimentally demonstrate a new amplification regime in which nonlinear spectral broadening is balanced by strong, longitudinally evolving gain-shaping. In contrast with conventional ultrafast amplifiers, in which the gain is static, in the GMN regime, the evolution of the gain spectrum is a complementary and previously unexplored degree of freedom. The distinct characteristic of this regime is a nonlinear attractor featuring extreme spectral broadening well beyond the gain bandwidth while producing pulses that can be compressed to nearly the transform limit.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment.

The authors acknowledge Logan G. Wright for fruitful discussions and helpful comments on the paper.

Funding. National Institutes of Health (EB002019).

Footnotes

See Supplement 1 for supporting content.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhao W, Hu X, and Wang Y, “Femtosecond-pulse fiber based amplification techniques and their applications,” IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron 20, 512.– (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fermann ME and Hartl I, “Ultrafast fibre lasers,” Nat. Photonics 7, 868.– (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fermann ME and Hartl I, “Ultrafast fiber laser technology,” IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron 15, 191.– (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strickland D and Mourou G, “Compression of amplified chirped optical pulses,” Opt. Commun 56, 219.– (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou S, Kuznetsova L, Chong A, and Wise FW, “Compensation of nonlinear phase shifts with third-order dispersion in short-pulse fiber amplifiers,” Opt. Express 13, 4869.– (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demmler S, Rothhardt J, Hädrich S, Krebs M, Hage A, Limpert J, and Tünnermann A, “Generation of high photon flux coherent soft x-ray radiation with few-cycle pulses,” Opt. Lett 38, 5051.– (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shank CV, Fork RL, Yen R, Stolen RH, and Tomlinson WJ, “Compression of femtosecond optical pulses,” Appl. Phys. Lett 40, 761.– (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zaouter Y, Papadopoulos DN, Hanna M, Boullet J, Huang L, Aguergaray C, Druon F, Mottay E, Georges P, and Cormier E, “Stretcher-free high energy nonlinear amplification of femtosecond pulses in rod-type fibers,” Opt. Lett 33, 107.– (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu W, Schimpf DN, Eidam T, Limpert J, Tünnermann A, Kärtner FX, and Chang G, “Pre-chirp managed nonlinear amplification in fibers delivering 100 W, 60 fs pulses,” Opt. Lett 40, 151.– (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen H-W, Lim J, Huang S-W, Schimpf DN, Kärtner FX, and Chang G, “Optimization of femtosecond Yb-doped fiber amplifiers for high-quality pulse compression,” Opt. Express 20, 28672.– (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson D, Desaix M, Karlsson M, Lisak M, and Quiroga-Teixeiro ML, “Wave-breaking-free pulses in nonlinear-optical fibers,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 10, 1185.– (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kruglov VI, Peacock AC, Dudley JM, and Harvey JD, “Self-similar propagation of high-power parabolic pulses in optical fiber amplifiers,” Opt. Lett 25, 1753.– (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fermann ME, Kruglov VI, Thomsen BC, Dudley JM, and Harvey JD, “Self-similar propagation and amplification of parabolic pulses in optical fibers,” Phys. Rev. Lett 84, 6010.– (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y, Li W, Luo D, Bai D, Wang C, and Zeng H, “Generation of 33 fs 935 W average power pulses from a third-order dispersion managed self-similar fiber amplifier,” Opt. Express 24, 10939.– (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song H, Liu B, Li Y, Song Y, He H, Chai L, Hu M, and Wang C, “Practical 24-fs, 1-μJ, 1-MHz Yb-fiber laser amplification system,” Opt. Express 25, 7559.– (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruglov VI and Harvey JD, “Asymptotically exact parabolic solutions of the generalized nonlinear Schrödinger equation with varying parameters,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 23, 2541.– (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soh DB, Nilsson J, and Grudinin AB, “Efficient femtosecond pulse generation using a parabolic amplifier combined with a pulse compressor II Finite gain-bandwidth effect,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 23, 10.– (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elahi P, Yılmaz S, Akçaalan Ö, Kalaycıoğlu H, Öktem B, Sęenel C, Ilday FÖ, and Eken K, “Doping management for high-power fiber lasers: 100 W, few-picosecond pulse generation from an all-fiber-integrated amplifier,” Opt. Lett 37, 3042.– (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elahi P, Yılmaz S, Eldeniz YB, and Ilday FÖ, “Generation of picosecond pulses directly from a 100 W, burst-mode, doping-managed Yb-doped fiber amplifier,” Opt. Lett 39, 236.– (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paschotta R, Nilsson J, Tropper AC, and Hanna DC, “Ytterbiumdoped fiber amplifiers,” IEEE J. Quantum Electron 33, 1049.– (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindberg R, Zeil P, Malmström M, Laurell F, and Pasiskevicius V, “Accurate modeling of high-repetition rate ultrashort pulse amplification in optical fibers,” Sci. Rep 6, 34742 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peacock AC, Kruhlak RJ, Harvey JD, and Dudley JM, “Solitary pulse propagation in high gain optical fiber amplifiers with normal group velocity dispersion,” Opt. Commun 206, 171.– (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson D, Desaix M, Lisak M, and Quiroga-Teixeiro ML, “Wave breaking in nonlinear-optical fibers,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 9, 1358.– (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson BP, Cotter D, Blow KJ, and Doran NJ, “Large nonlinear pulse broadening in long lengths of monomode fibre,” Opt. Commun 48, 292.– (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez OE, Gordon JP, and Fork RL, “Negative group-velocity dispersion using refraction,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1, 1003.– (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kruglov VI, Aguergaray C, and Harvey JD, “Parabolic and hyper-Gaussian similaritons in fiber amplifiers and lasers with gain saturation,” Opt. Express 20, 8741.– (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chong A, Buckley J, Renninger W, and Wise F, “All-normal-dispersion femtosecond fiber laser,” Opt. Express 14, 10095.– (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong YC, Chan LY, and Tsang HK, “Fibre dispersion or pulse spectrum measurement using a sampling oscilloscope,” Electron. Lett 33, 983.– (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeLong KW, Trebino R, Hunter J, and White WE, “Frequency-resolved optical gating with the use of second-harmonic generation,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 11, 2206.– (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shapira YP, Smulakovsky V, and Horowitz M, “Experimental demonstration of nonlinear pulse propagation in a fiber Bragg grating written in a fiber amplifier,” Opt. Lett 41, 5.– (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kashyap R, “Principles of optical fiber grating sensors,” in Fiber Bragg Gratings (Elsevier, 2010), pp. 441–502. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erdogan T, “Fiber grating spectra,” J. Lightwave Technol 15, 1277.– 1294 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rana F, Lee HLT, Ram RJ, Grein ME, Jiang LA, Ippen EP, and Haus HA, “Characterization of the noise and correlations in harmonically mode-locked lasers,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 19, 2609.– (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Z, Ziegler ZM, Wright LG, and Wise FW, “Megawatt peak power from a Mamyshev oscillator,” Optica 4, 649.– (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sidorenko P, Fu W, Wright LG, Olivier M, and Wise FW, “Selfseeded, multi-megawatt, Mamyshev oscillator,” Opt. Lett 43, 2672.– 2675 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fedotov A, Noronen T, Gumenyuk R, Ustimchik V, Chamorovskii Y, Golant K, Odnoblyudov M, Rissanen J, Niemi T, and Filippov V, “Ultra-large core birefringent Yb-doped tapered double clad fiber for high power amplifiers,” Opt. Express 26, 6581.– (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beier F, Möller F, Sattler B, Nold J, Liem A, Hupel C, Kuhn S, Hein S, Haarlammert N, Schreiber T, Eberhardt R, and Tünnermann A, “Experimental investigations on the TMI thresholds of low-NA Yb-doped single-mode fibers,” Opt. Lett 43, 1291.– (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krupa K, Tonello A, Shalaby BM, Fabert M, Barthélémy A, Millot G, Wabnitz S, and Couderc V, “Spatial beam self-cleaning in multimode fibres,” Nat. Photonics 11, 237.– (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scott A, Encyclopedia of Nonlinear Science (Routledge, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott A, The Nonlinear Universe, The Frontiers Collection (Springer, 2007). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.