Abstract

Rationale

Oxycodone is one of the most widely prescribed pain-killers in the USA. However, its use is complicated by high abuse potential. As sex differences have been described in drug addiction, the present study tested for sex differences in intravenous oxycodone self-administration in rats.

Methods

Male and female Sprague-Dawley rats were implanted with jugular vein catheters and trained to self-administer oxycodone (0.03 mg/kg/infusion) under fixed ratio 1 (FR1), FR2, and FR5 schedules of reinforcement followed by a dose-response study to assess sensitivity to the reinforcing effects of oxycodone. In separate rats, sucrose pellet self-administration was assessed under an FR1 schedule to determine whether sex differences in oxycodone self-administration could be generalized across rein-forcers. In separate rats, oxycodone distribution to plasma and brain was measured after intravenous drug delivery.

Results

In the first 3 trials under an FR1 schedule of reinforcement, male rats self-administered more oxycodone than females. In contrast, females self-administered more sucrose pellets. Under FR2 and FR5 schedules, no significant sex differences in oxycodone intake were observed, although female rats had significantly more inactive lever presses. Male and female rats showed similar inverted U-shaped dose-effect functions, with females tending to self-administer more oxycodone than males at higher doses. No significant sex differences were observed in plasma or brain oxycodone levels, suggesting that sex differences in oxycodone self-administration behavior were not due to pharmacokinetics.

Conclusion

Our results suggest subtle sex differences in oxycodone self-administration, which may influence the abuse liability of oxycodone and have ramifications for prescription opioid addiction treatment.

Keywords: Oxycodone, Sex differences, Self-administration, Sucrose reward, Motivation

Introduction

Over the last decade, prescription opioid abuse in the USA has increased to epidemic levels (Compton et al. 2016). In 2014, over 10 million people reported non-medical use of prescription opioids, and there were approximately 19 thousand reported over-dose deaths (Compton et al. 2016). Oxycodone is a semisynthetic opioid analgesic derived from thebaine, a minor constituent of opium (Kimishima et al. 2014). Oxycodone is prescribed for acute and chronic pain and, at least in some countries, has replaced morphine as the most widely prescribed opioid painkiller (Soderberg Lofdal et al. 2013). Pharmacologically, oxycodone is a moderately selective mu opioid receptor (MOR) agonist, with a lower affinity for MOR than morphine and low affinities for delta and kappa opioid receptors (Olkkola et al. 2013). The permeability of oxycodone across the blood brain barrier is seven-fold higher than that of morphine, and it shows a faster onset and a longer duration of action than morphine (Olkkola et al. 2013). Together with fewer side effects (Compton et al. 2016) and its powerful actions on reward circuitry, oxycodone is one of the most highly abused drugs available today.

Historically, drug abuse has been more prevalent in men than in women. However, this gender gap is narrowing as women are abusing prescription opioids equally or more so than men (Simoni-Wastila et al. 2004). Additionally, women are more likely than men to report using opioids to manage stress (McHugh et al. 2013), and it has been reported that women progress from initial opioid abuse to opioid use disorder faster than men (Hernandez-Avila et al. 2004). As such, increasing evidence suggests that the prescription opioid epidemic disproportionally affects women (Chartoff and McHugh 2016). Unfortunately, there are limited preclinical studies assessing potential sex differences in opioid addiction. Rodent studies have shown that female rats acquire heroin self-administration faster than male rats do in a long access, fixed ratio 1 (FR1) schedule of reinforcement, although total heroin intake does not differ (Lynch and Carroll 1999). Female rats have been reported to exhibit an upward shift in a heroin dose-response compared to males, with no significant sex differences in food self-administration (Cicero et al. 2003), raising the possibility that females have increased vulnerability to opioid addiction. To our knowledge, oxycodone self-administration has been studied only in male rats and mice (Beardsley et al. 2004; Pravetoni et al. 2014; Wade et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2014). Sex comparisons are important to study because they can unravel sex-specific behaviors and ultimately help us identify targeted therapeutic strategies. The present study was designed to assess oxycodone self-administration in male and female rats to identify similarities and/or differences between sexes. Drug self-administration in rodents is a well-validated paradigm to study the neurobiological basis of addiction (Koob 1992).

Materials and methods

Animals

Age-matched (75–80 days old at arrival) adult male (325–350 g; n = 26) and female (225–250 g; n = 28) Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratory, Wilmington, MA) were used for this study. Upon arrival, rats were group-housed by sex (4 rats/cage) and were acclimated for 1 week in a 12-h light-dark cycle with food and water ad libitum. Rats were singly housed during self-administration studies. All experiments were conducted during the light phase. All guidelines recommended by the Animal Care and Use Committee of McLean Hospital were followed.

Determination of estrous cycle stage

Vaginal lavage was performed immediately after each self-administration trial, and epithelial cytology was assessed to determine estrous stage (Hubscher et al. 2005). Males were handled for a similar amount of time. Harris hematoxylin and Eosin Y staining was performed on dried vaginal cells (Russell et al. 2014). Proestrus, which lasts 12–14 h, was identified by the predominance of round, nucleated epithelial cells. Estrus, which lasts 25–27 h, was identified by the presence of dense sheets of cornified, non-nucleated epithelial cells. Metestrus, which lasts 6–8 h, was identified by the presence of many leukocytes and scattered nucleated cells. Diestrus, which lasts 55–57 h, was identified by a low density of both leukocytes and nucleated cells.

Intravenous catheter implantation

Rats were implanted with chronic indwelling silastic (0.51 mm internal diameter) intravenous jugular catheters as in (Thomsen and Caine 2005). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with a ketamine/xylazine mixture (80 mg/kg ketamine and 8 mg/kg xylazine, i.p.), and catheters were implanted into the right jugular vein, secured to the vein by non-absorbable suture thread, and passed subcutaneously to exit dorsally to the rat’s back. Catheters were flushed daily with 0.2 ml of heparinized saline (30 USP units/ml) and once/week with 0.2 ml gentamycin (10 mg/ml).

Apparatus for oxycodone self-administration

Operant conditioning chambers (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT; 30.5 × 24.1 × 29.2 cm) were equipped with two retractable response levers with cue lights above them, a house light, a counterbalanced fluid swivel and tether, and an infusion pump. The chambers were enclosed in sound-attenuated cubicles with ventilation fans. A spring-covered Tygon tube was connected to the rat’s catheter through a fluid swivel to a syringe that contained oxycodone solution. The syringe was placed in an infusion pump located outside the chamber. A press on the active lever resulted in a 4-s long infusion of oxycodone hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in 0.9% bacteriostatic saline. The concentration of oxycodone solution in each syringe was adjusted to the rat’s body weight and updated to account for body weight changes at least once/week such that each rat received 100 μl per infusion. Males weighed 430.3 g ± 13.8 SEM at the start of the study and 513.3 g ± 14.61 SEM on trial 10 of FR5; females weighed 275.5 g ± 9.25 at the start and 320.2 g ± 9.31 on trial 10 of FR5. MED-PC software and interfacing (MED Associates) controlled the apparatus and data recording. Rats were trained in designated sex-specific chambers.

Oxycodone self-administration studies

One week after surgery, rats began oxycodone self-administration training under an FR1 schedule of reinforcement. To facilitate acquisition of drug self-administration, rats were fasted overnight (17–18 h) for the first 3 trials of FR1 training. To encourage pressing on the active lever, food dust was sprinkled on the active lever prior to trials 1 and 2. Under the FR1 schedule, each active lever press resulted in an infusion of 0.03 mg/kg oxycodone. Immediately after each self-administration trial, food was again available ad libitum to maximize the time rats were able to eat. From trial 4 onward, rats were maintained on ad libitum feeding conditions.

Self-administration trials were 1 h long and were conducted 6 days per week. Each trial began with onset of the house light, and levers were extended to signal drug availability. Each infusion (4 s) was signaled by the onset of a cue light over the active lever and offset of the house light. A 6-s timeout period was initiated at the start of each infusion and, during that period, any press on the active lever had no consequence. Following the timeout period, the cue light turned off and the house light turned on to signal drug availability. Throughout the trials, presses of the inactive lever were recorded but had no consequences. We recorded and analyzed active lever presses, which include presses that led to a drug infusion and those that did not (i.e., lever is pressed during a timeout), inactive lever presses, and total infusions.

Rats were trained for a minimum of 10 trials (1 trial/day) under an FR1 schedule. If at the end of the 10 trials a rat had achieved a minimum of five infusions per trial for 3 consecutive trials, it was shifted to an FR2 schedule of reinforcement. If not, the rat was maintained on FR1 until this requirement was met. After 5 trials on FR2, rats were shifted to an FR5 schedule for a minimum of 10 consecutive trials. To transition from the FR5 trials to the dose-response experiment, rats were required to meet stability criteria, which consisted of a minimum of five infusions per trial, less than 10% variation in intake, and an active:inactive lever press ratio of at least 2:1 in the last 3 trials. To initiate dose-response testing, oxycodone was replaced with saline for 3 consecutive trials to ensure that rats could discriminate oxycodone from saline and to minimize nonspecific responses to saline. In the dose-response test, rats self-administered increasing doses of oxycodone (0.0003, 0.003, 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, and 0.3 mg/kg/infusion) in daily 1-h trials.

Methohexital sodium (2 mg in 0.2 ml, i.v.) was infused to test catheter patency once every 7–10 days, if self-administration behavior rapidly and significantly changed, and on the last trial at FR5. Any rats that did not have patent catheters during the FR1-FR5 trials or during subsequent dose-response testing were excluded. Attrition for males (n = 14 at start) was due to failed catheters during FR1-FR5 trials (n = 2), failed catheters before or during dose response (n = 3), and patent catheters but complete cessation of operant responding during the dose response (n = 3). Attrition for females (n = 14 at start) was due to failed catheters during FR1-FR5 trials (n = 3), failed catheters before or during the dose response (n = 3), and sickness during dose response (n = 1).

Apparatus for sucrose pellet self-administration

A different set of operant conditioning chambers (Med Associates; 30.5 × 24.1 × 21 cm) was used for sucrose pellet self-administration. These chambers were equipped with two retractable response levers that had a cue light above each, a house light, and a food hopper. The chambers were enclosed in sound-attenuated cubicles equipped with ventilation fans. An active lever press resulted in the delivery of a 45-mg sucrose pellet (Dustless Precision Pellets 45 mg, 30.2% sucrose, BioServ). Conditional stimuli (light cue and house light) were kept consistent with oxycodone self-administration. Male and female rats were trained in designated sex-specific chambers.

Sucrose pellet self-administration

Sucrose pellet self-administration was conducted for 3 trials (1 trial/day) in a new cohort of drug-naïve rats (n = 8 males, 8 females). Before the first trial, rats were fasted overnight (17–18 h) as was done for oxycodone self-administration. Rats were trained to respond under an FR1 schedule in which each active lever press resulted in the drop of a sucrose pellet. Food was available ad libitum following the self-administration trials.

Oxycodone concentration in brain and plasma

For repeated blood sampling, a new cohort of drug-naïve rats was implanted with i.v. jugular catheters and singly housed (n = 4 males, 6 females). After 1 week of recovery, oxycodone (0.15 mg/kg) was delivered through the catheters. This dose is the equivalent of five infusions of the training dose (0.03 mg/kg/infusion) of oxycodone, which was the minimum number of infusions required for stability. Blood samples (200 μl) were withdrawn via the catheters before oxycodone infusion and 5, 15, 30, and 60 min post-infusion. One male was excluded from this analysis because blood could not be withdrawn from the catheter. One female rat was excluded from the remainder of the study because of a faulty catheter.

One week later, the same rats (n = 4 males, 5 females) used for the repeated blood draws were administered oxycodone (0.15 mg/kg, i.v.) to compare oxycodone levels in the brain and plasma. Five minutes after drug infusion, rats were decapitated and their brains removed and frozen in isopentane kept on dry ice. Trunk blood was collected in 15-ml tubes containing 0.25 ml 3 M EDTA on wet ice. Blood was centrifuged at 13,000g for 15 min, and plasma was extracted and frozen at −80 °C. Brains were homogenized and processed for oxycodone measurements. Gas chromatography paired to mass spectrometry was used to measure oxycodone concentrations, as in (Pravetoni et al. 2012). In this assay, the limit of quantitation is 5 ng/ml oxycodone in plasma and 25 ng/g in brain samples. Any value under these limits was considered zero.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Lever press data (Figs. 1a, c; 2a, c; 4a) were analyzed using linear mixed-effects models set to detect interactions and main fixed effects between sex, lever, and trial. If no significant interactions were detected, the interaction was dropped from the analysis to detect main effects. Total infusion/consumption data (Figs. 1b, d; 2b, d; 4b, c) and plasma oxycodone time-course data (Fig. 5a) were analyzed using linear mixed-effects models set to detect interactions and main fixed effects between sex and trial/time. If no significant interactions were detected, the interaction was dropped from the analysis to detect main fixed effects. If significant interactions were detected, Bonferroni’s post hoc tests for multiple comparisons were done. Brain and plasma oxycodone levels (Fig. 5b, c) were analyzed with Student’s t tests.

Fig. 1. a.

Active and inactive lever presses and b total number of oxycodone infusions (0.03 mg/kg/infusion) under an FR1 schedule of reinforcement in male (n = 12) and female (n = 11) rats with overnight fasting. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; Black circles and white circles indicate active lever presses () or infusions (b) in males and females respectively; Black squares and white squares indicate inactive lever presses in males and females respectively (); *p < 0.05 main effect of sex. c Active and inactive lever presses for sucrose and d total sucrose consumed (mg of sucrose adjusted to body weight). There are eight rats/sex (n = 8/sex). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Black circles and white circles indicate active lever presses (c) or infusions (d) in males and females respectively; Black squares and white squares indicate inactive lever presses in males and females respectively (c); ++p < 0.01 and +++p < 0.001 compared to the males on the same trial

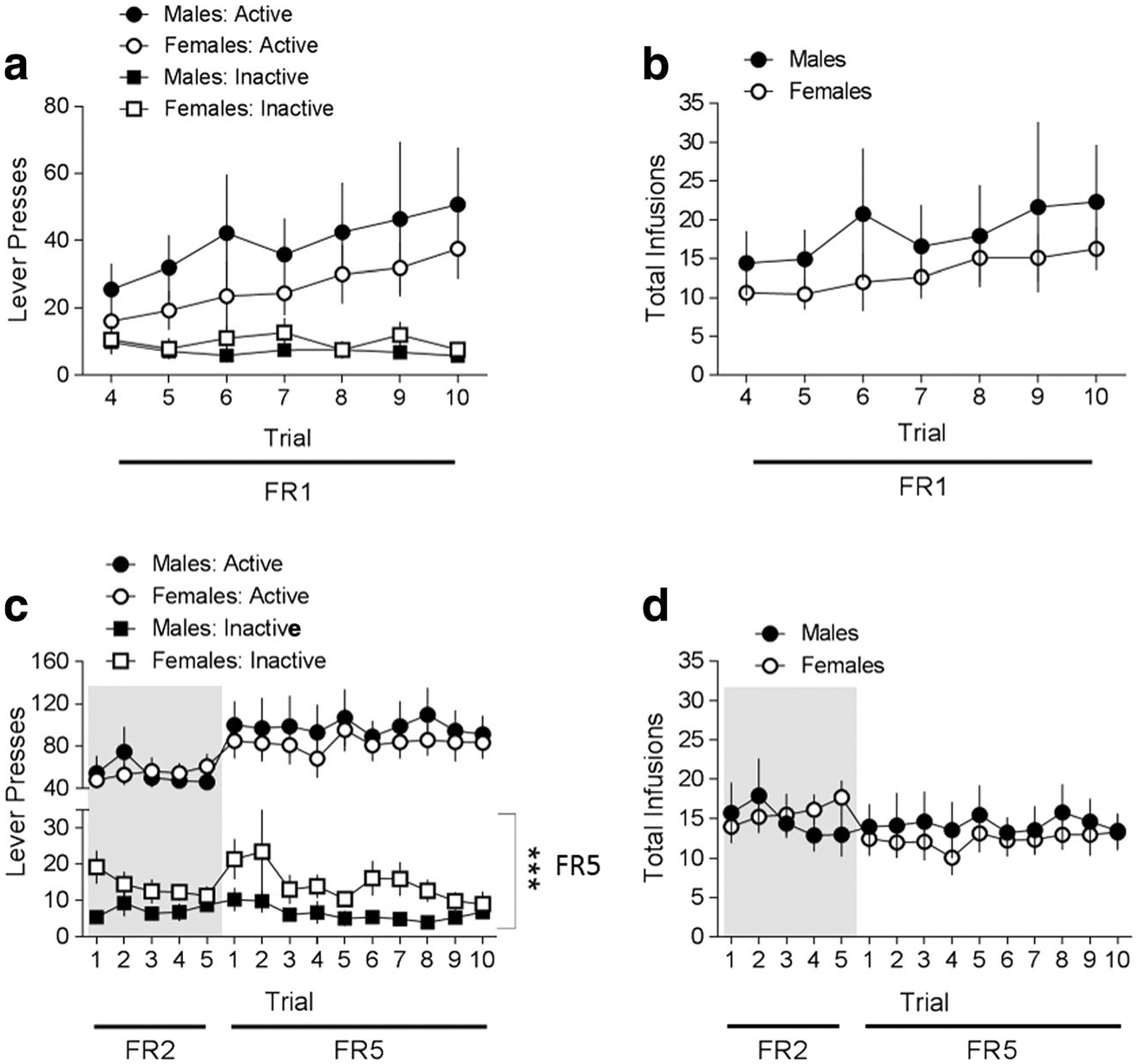

Fig. 2. a.

Active and inactive lever presses and b total number of oxycodone infusions under FR1 schedule of reinforcement and ad libitum feeding conditions in male (n = 12) and female (n = 11) rats. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; Black circles and white circles indicate active lever presses (a) or infusions (b) in males and females respectively; Black squares and white squares indicate inactive lever presses in males and females respectively (). c Active and inactive lever presses and d total number of oxycodone infusions under FR2 and FR5 schedule of reinforcement and ad libitum feeding conditions in the same male (n = 12) and female (n = 11) rats. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; Black circles and white circles indicate active lever presses (c) or infusions (d) in males and females respectively; Black squares and white squares indicate inactive lever presses in males and females respectively (c). The gray background represents results collected under an FR2 schedule of reinforcement. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; ***p < 0.0001 main effect of sex for inactive lever presses

Fig. 4.

Oxycodone was replaced by saline for 3 consecutive trials and a active and inactive lever presses and b total number of infusions were assessed. There are six males (n = 6) and seven females (n = 7). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; Black circles and white circles indicate active lever presses (a) or infusions (b) in males and females respectively; Black squares and white squares indicate inactive lever presses in males and females respectively (a). The gray background represents results collected on the last day of oxycodone self-administration. c Total number of oxycodone infusions during the dose-response in which rats self-administered ascending doses of oxycodone (0.0003–0.3 mg/kg/infusion; one dose per trial/day) in 1-h trials under an FR5 schedule of reinforcement. There are six males (n = 6) and seven females (n = 7). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; Black circles and white circles indicate total number of oxycodone infusions in males and females respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05 main effect of sex

Fig. 5. a.

Oxycodone distribution in plasma; before (Time = 0) and after (Time = 5, 15, 30, and 60 min) a single injection of oxycodone (0.15 mg/kg, i.v.). There are three males (n = 3) and five females (n = 5). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; Black circles and white circles indicate oxycodone levels in plasma in males and females respectively. Oxycodone was measured in b plasma and c brain 5-min post-infusion (0.15 mg/kg, i.v.). There are four males (n = 4) and five females (n = 5). Data are presented as mean ± SEM; The black bars represent oxycodone levels in males and the white bars represent oxycodone levels in females

Results

Oxycodone self-administration under an FR1 schedule of reinforcement with initial food restriction

Data from the first 3 trials of self-administration training under an FR1 schedule of reinforcement were analyzed separately from the remainder of the FR1 trials (trials 4–10) because rats were initially fasted overnight prior to each of the first 3 trials, and rat chow dust was sprinkled on the active levers to promote lever pressing for the first 2 trials. Males and females (n = 12 males, 11 females) showed similar patterns of active and inactive lever presses over the first 3 trials (no sex × lever × trial interaction, p > 0.05) and had significantly more presses on the active lever compared to the inactive lever [main effect of lever (F(1,21) = 46.275, p < 0.0001); Fig. 1a]. Both males and females showed a similar, albeit small, trend for increasing numbers of active lever presses over the first 3 trials [trend for a main effect of trial (F(2,22) = 2.700, p = 0.089); Fig. 1a]. Although males tended to have more active lever presses than females during these first 3 trials (mean active lever presses, trials 1–3: male, 38.67 ± 7.03 SEM; female, 24.64 ± 4.06 SEM), as shown by a trend for a main effect of sex [F(1,21) = 3.618, p = 0.071; Fig. 1a], this did not reach significance. Likewise, there was no sex difference in the number of inactive lever presses (mean inactive lever presses, trials 1–3: male, 2.83 ± 0.77 SEM; female, 3.45 ± 0.98 SEM), as shown by no main effect of sex (p > 0.05). Since active lever presses consist of presses that lead to drug infusion and presses during timeout periods, we also analyzed the number of actual drug infusions (Fig. 1b). As with active lever presses, males and females showed a similar pattern of total oxycodone infusions over the first 3 trials (no sex × trial interaction, p > 0.05). However, males self-administered significantly more oxycodone infusions than females [main effect of sex, (F(1,21) = 5.061, p < 0.05); Fig. 1b].

Sucrose pellet self-administration under an FR1 schedule of reinforcement with initial food restriction

To determine whether male rats would self-administer more of a non-drug reward than females under similar experimental conditions, we tested a separate cohort of experimentally naive male and female rats with sucrose pellet self-administration under an FR1 schedule of reinforcement (n = 8 males, 8 females). In contrast to oxycodone self-administration, in which males and females showed a similar pattern of behavior, there was a robust sex difference in responding on the active, but not the inactive, lever [sex × lever × trial interaction F(2,14) = 9.145, p = 0.003; Fig. 1c]. Specifically, females showed a dramatic increase in responding on the active lever over the 3 trials, with responding significantly greater than males on trial 3. When data were analyzed as the total amount (in mg) of sucrose pellets consumed in a trial, adjusted for body weight, there was a significant sex difference over time [sex × trial interaction (F(2,14) = 13.737, p < 0.0001); Fig. 1d], with female rats consuming significantly more compared to male rats on trials 2 and 3.

Oxycodone self-administration under FR1, FR2, and FR5 schedules of reinforcement

After the first 3 trials of oxycodone self-administration training under food-restricted conditions, rats (n = 12 males, 11 females) were returned to ad libitum feeding. Rats continued to self-administer oxycodone under an FR1 schedule of reinforcement for an additional 7 trials (trials 4–10). As with behavior during the first 3 trials, males and females showed similar patterns of lever pressing over trials 4–10 (no sex × lever × trial interaction, p > 0.05), with both sexes having significantly more presses on the active compared to the inactive lever [main effect of lever (F(1,21) = 9.331, p = 0.006); Fig. 2a]. Males and females increased the number of active lever presses over time [main effect of trial (F(6, 22) = 6.180, p = 0.001); Fig. 2a], and there was no sex difference in active lever presses (no effect of sex, p > 0.05). As with active lever presses, males and females showed a similar, increasing pattern of total oxycodone infusions over trials (no sex × trial interaction, p > 0.05, and no main effect of sex, p > 0.05), but a main effect of trial [(F(6, 22) = 4.670, p = 0.003); Fig. 2b].

To advance to the FR2 schedule of reinforcement, rats were required to self-administer at least 5 oxycodone infusions for 3 consecutive trials. On trial 10 of FR1, 75% of males (9/12 rats) and 73% of females (8/11 rats) met these criteria. Rats that did not meet these criteria continued to be tested on an FR1 schedule. The mean number of trials on FR1 for males was 10.58 ± 0.35 (SEM) and for females was 11.18 ± 0.75 (SEM). Rats self-administered oxycodone on an FR2 schedule for 5 trials and moved automatically to a final FR5 schedule for a minimum of 10 trials. To be moved from FR5 to the dose-response component of the study, rats were required to fulfill stability criteria (see Materials and methods). On trial 10 of FR5, 25% of males (3/12 rats) and 18% of females (2/11 rats) met the criteria. Rats that did not meet these criteria continued to be tested on an FR5 schedule. The mean number of trials on FR5 for males was 15.42 ± 1.61 (SEM) and for females was 13.36 ± 0.95 (SEM).

Under FR2 and FR5 schedules of reinforcement, male and female rats displayed similar oxycodone self-administration behavior (no sex × lever × trial interaction, p > 0.05; Fig. 2c); however, females had more inactive presses under FR5 conditions (F(1, 21) = 0.70, p = 0.794 for FR2 and F(1, 21) = 21.455, p < 0.0001 for FR5; Fig. 2c). The total number of oxycodone infusions over the trials was not different between males and females [no sex × trial interaction, p > 0.05; Fig. 2d].

Patterns of oxycodone intake in male and female rats

Previous research has shown that, under some self-administration conditions, rats can be considered either high or low responders (Piazza et al. 1989; Puhl et al. 2013). Therefore, we examined the distribution of total intake and patterns of oxycodone self-administration during the 10 trials under an FR5 schedule of reinforcement. The total number of infusions obtained on trials 1–10 of the FR5 schedule of reinforcement was similar in male and female rats (Fig. 3a). Although there were no clear high or low responder subpopulations in either the male or female groups, there was a larger distribution of total infusions in the males compared to the females. To examine patterns of self-administration, we selected male and female rats that self-administered the most oxycodone (intake above the mean) and the least oxycodone (intake below the mean) on trial 10 of FR5 and used raster plots to represent each infusion as a vertical tick across time (Fig. 3b). In general, male and female rats that took the most drug (Fig. 3bi, ii) self-administered oxycodone at a higher frequency during the first 10–15 min compared to the remaining 45–50 min of the 1-h trials. Males self-administered an average of 7.75 ± 2.496 SEM infusions in the first 10 min out of a total of 25.25 ± 2.394 SEM infusions for the 60-min trial, whereas females self-administered an average of 10 ± 1.472 SEM infusions in the first 10 min out of a total of 23.75 ± 3.038 SEM infusions. In contrast, rats that took the least amount of drug (Fig. 3biii, iv) self-administered oxycodone at more regular and low frequencies.

Fig. 3. a.

The total number of oxycodone infusions during trials 1–10 under the FR5 schedule were plotted for each male and female rat. b Representative drug infusion patterns are plotted for male and female rats that showed either high or low intake compared to the mean of total intake (represented by horizontal lines in a). c Estrous cycles are plotted for each female rat over the 25 trials comprising FR1, FR2, and FR5 schedules of reinforcement. Dark gray squares represent days on which cell types corresponded to estrus. Light gray squares represent days on which estrus would be predicted to occur based on the preceding and following days’ cytology or days in which epithelial cytology was an intermediate of estrus and either proestrus or metestrus

We assessed the estrous cycle of each female rat over the course of the 25 trials under FR1, FR2, and FR5 schedules of reinforcement (Fig. 3c). By plotting the discrete instances in which vaginal epithelial histology indicated estrus or an intermediate stage of estrus and either proestrus or metestrus, we show a normal pattern of cycling. On average, estrus was detected 22% of the time, which matches the expected frequency given the rat’s 4–5-day estrous cycle.

Oxycodone dose-response in male and female rats

After the last trial of oxycodone self-administration under the FR5 schedule of reinforcement, which was different for each rat depending on how long it took to achieve stability, operant behavior at the active lever was reduced by substituting saline for oxycodone in 3 consecutive trials (n = 6 males, 7 females). Under these “extinction” conditions, both males and females responded in a similar manner: they decreased responding on the active lever over the 3 saline trials but did not change responding on the inactive lever over time (no sex × lever × trial interaction, p > 0.05; Fig. 4a). Active lever presses decreased over the 3 saline trials [main effect of trial, (F(2,12) = 6.423; p = 0.013); Fig. 4a], but there was no significant effect of trial on inactive lever presses (p > 0.05). There were no sex differences in pressing on either the active or inactive levers (p > 0.05). Similar to active lever pressing, the total number of saline infusions self-administered by males and females was similar over the 3 saline trials (no sex × trial interaction, p > 0.05; Fig. 4b) and decreased over time [main effect of trial (F(2,12) = 6.806; p = 0.011)]. There were no sex differences in the number of infusions (no main effect of sex, p > 0.05).

After the third trial of extinction conditions, the dose-response experiment was initiated with a low dose of oxycodone (0.0003 mg/kg/infusion). Doses (one per trial) were presented in ascending order on each subsequent 1-h trial. Both males and females showed similar inverted U-patterns of drug taking in the dose response (no sex × dose interaction, p > 0.05; Fig. 4c), with dose-dependent increases and decreases in infusions [main effect of dose (F(5, 9) = 8.732, p = 0.003)]. Overall females self-administered more oxycodone than males in the dose response function, which is reflected in a significant main effect of sex (F(1, 11) = 6.709, p < 0.05). However, an important caveat is that there was a greater attrition of male rats that demonstrated high total infusions in FR5 (see Fig. 3a and Materials and methods) compared to females.

Oxycodone distribution in plasma and brain

To determine whether oxycodone pharmacokinetics differed between male and female rats, we measured oxycodone distribution in the plasma and brain. In a time-course experiment, we found that peak oxycodone levels were detected 5 min after i.v. infusion. Oxycodone was below the limit of quantification at 0 or 60 min post-infusion, so these time points were not included in our analysis. Oxycodone distribution in plasma was similar between males and females over time (no sex × time interaction, p > 0.05; Fig. 5a), and there were no sex differences (no main effect of sex, p > 0.05). Oxycodone levels showed a peak and then significantly decreased over time [main effect of time (F(2, 6) = 11.250, p = 0.009)]. To directly compare the brain versus plasma distribution of oxycodone, we collected trunk blood and brains from rats 5 min after i.v. oxycodone administration. There were no significant differences in oxycodone levels in either plasma or brain (p > 0.05; Fig. 5b, c).

Discussion

In this study, we assessed oxycodone self-administration behavior and pharmacokinetics in male and female rats to test for sex differences and similarities. Under our experimental conditions, both male and female rats acquired self-administration behavior at similar rates. During the first 3 trials, in which rats were fasted overnight, males self-administered more oxycodone than females. However, this sex difference could not be generalized to self-administration of all rewards, as female rats self-administered significantly more sucrose pellets compared to males on the first 3 trials of FR1 training under the same fasting conditions used for oxycodone. As male and female rats continued to self-administer oxycodone under an FR1 schedule of reinforcement, with ad libitum feeding conditions, males consistently self-administered more oxycodone; however, this effect was not significant. As the schedule of reinforcement was increased to FR2 and then FR5, sex differences in drug intake disappeared. Males and females showed similar oxycodone dose-response functions, with 0.01 mg/kg eliciting the greatest response. Oxycodone self-administration did not disrupt the estrous cycle. Finally, there were no sex differences in oxycodone distribution in plasma and brain, suggesting that sex differences in oxycodone pharmacokinetics do not play a major role in sex differences in self-administration behavior.

The rate of acquisition and patterns of oxycodone self-administration behavior were similar between male and female rats. This appears to contrast with prior studies in rodents that have reported faster acquisition rates and a higher percentage of MOR agonist self-administration acquisition behavior in females compared to males (Carroll et al. 2002; Cicero et al. 2003; Lynch and Carroll 1999). Importantly, however, these studies used long-access self-administration protocols, which are fundamentally different than the protocol used in this study. We observed that male rats self-administered significantly more oxycodone than females in the first 3 trials when rats were fasted, and there was a trend for males to self-administer more drug in the remaining FR1 trials when food was available ad libitum. Previous studies on sex differences in total intake of MOR agonists in laboratory animals are equivocal, with some studies showing females self-administering more drugs (Cicero et al. 2003; Stewart et al. 1996) and others showing no sex differences (Lynch and Carroll 1999). Importantly, differences in animal strains and methodologies among the studies make direct comparisons impossible.

The two largest differences in methodology between our study and earlier works are (1) the drug itself and (2) that rats underwent food restriction for the first 3 trials of exposure to oxycodone. There is substantial evidence that food restriction can potentiate opioid self-administration in both males and females (Carr 2002; Carroll et al. 2001; Lu et al. 2003). However, previous preclinical work indicates that food restriction potentiates MOR agonist self-administration more in females than in males (Carroll et al. 2001). Taken together, the unique pharmacological effects of oxycodone may result in greater initial intake in males. Consistent with this, a recent study in male rats demonstrated that oxycodone evokes larger and longer-lasting increases in dopamine release compared to morphine in the ventral striatum (Vander Weele et al. 2014). Although it is not known whether there are sex differences in terms of the impact of oxycodone on dopamine release, it is known that stimulated dopamine release in the striatum is greater in females compared to males (Walker et al. 2000). This raises the possibility that oxycodone elicits less dopamine release in males compared to females, rendering males less sensitive to the rewarding effects of oxycodone and requiring males to self-administer more drug to obtain the same effect. An alternate explanation for why males self-administer greater amounts of oxycodone than females in the first several trials of acquisition training is that females are more sensitive than males to the aversive effects of the drug and as such take less drug. This is supported by a clinical study in which healthy women demonstrated larger oxycodone-induced dysphoric effects compared to men (Zacny and Drum 2010). In future studies, a behavior such as intracranial self-stimulation could determine if there are sex differences in either the rewarding or the aversive effects of oxycodone, whereas a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement in the self-administration paradigm could determine if there are sex differences in the reinforcing efficacy of oxycodone. Regardless, our data suggest that plasma and brain levels of oxycodone are similar in males and females, suggesting that sex differences in pharmacokinetics are not a major factor in behavioral response. However, since our study only examined brain oxycodone levels at one time point (5 min), it is possible that there are sex differences in the offset or removal of oxycodone from the brain.

Female rats demonstrated significantly more inactive lever presses compared to male rats under an FR5 schedule of reinforcement. This is broadly consistent with preclinical findings that females are more sensitive to the locomotor stimulant effects of opioids (Craft 2008; Craft et al. 2006; Craft et al. 1996). For example, it has been reported that females show enhanced oxycodone-induced hyperlocomotion compared to males and respond to lower oxycodone doses (Collins et al. 2016). Also, greater locomotor sensitization following repeated morphine treatment has been observed in female compared to male mice (Zhan et al. 2015). Notably, the increased level of inactive lever presses in female compared to male rats was only evident after at least 10 trials of oxycodone self-administration. Chronic estradiol has been shown to enhance the locomotor stimulant effects of MOR opioids in females (Craft 2008). However, we show that oxycodone self-administration did not alter the estrous cycle in our study, which differs from previous work using chronic, experimenter-administered morphine (Craft et al. 1999).

Female rats self-administered more sucrose pellets than males and escalated their intake over the 3-trial period, whereas male rats did not. These findings contrast with previous studies showing that male and female rats self-administer comparable amounts of sucrose under FR2, 4, and 5 schedules of reinforcement (Bardo et al. 2001). It has also been shown that male rats self-administer more food rewards (van Hest et al. 1989) yet similar amounts of sucrose (Zhou et al. 2015) compared to females. In the abovementioned studies, rats were maintained at 85% of their original body weights, while in our study rats were maintained at 93–97% body weight. Furthermore, studies comparing sucrose preference in male and female rats are equivocal (Curtis et al. 2004; Sclafani et al. 1987; Valenstein et al. 1967), which is likely due to differences in experimental design and palatability of food rewards.

Dose-effect functions can reveal differences in sensitivity and vulnerability to a drug’s reinforcing properties through horizontal and vertical shifts, respectively (Piazza et al. 2000). In our study, we observed that females tended to self-administer more oxycodone than males, indicative of an upward shift in the dose-effect function. An upward shift has been interpreted as an increase in vulnerability to abuse and addiction because animals in which dose-effect functions are shifted upwards tend to self-administer drugs at faster rates and hence take more drugs across a wide range of available doses (Piazza et al. 2000). Our findings are similar to previous research showing that female rats self-administered more heroin compared to male rats at all doses tested (Cicero et al. 2003). In our study, it is possible that the prior 25 trials of oxycodone self-administration experience sensitized female rats to the drug, such that operant behavior was greater in female rats compared to males. One caveat is that 3 of the 6 males that failed to complete the dose-response (see Methods) had self-administered relatively high amounts of oxycodone, whereas the females that failed to complete the dose response had self-administered relatively low amounts of oxycodone.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate subtle sex differences in oxycodone self-administration behavior that do not appear to depend on oxycodone pharmacokinetics or alterations in estrous cycling. On balance, however, oxycodone self-administration under the current set of conditions was broadly similar in males and females. Future studies that model aspects of addictive behavior such as escalation of intake, reinstatement, and motivation to work for drug may reveal additional sex differences. This is important, since human studies indicate that women are at higher risk compared to men to misuse prescription opioids (Hemsing et al. 2016).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Brooking Fellowship (MM). We thank Dr. Linda Valerie for the critical assistance with the statistical analysis of the results of this study. We also thank Dr. Maria Carreira for training MM in the jugular vein catheterization and relevant self-administration procedures, Dr. In-Jee You for the recommendations for setting up the drug self-administration paradigm, and Dr. Barak Caine and Dr. Morgane Thomsen for commenting on our data.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

All guidelines recommended by the Animal Care and Use Committee of McLean Hospital were followed.

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Bardo MT, Klebaur JE, Valone JM, Deaton C (2001) Environmental enrichment decreases intravenous self-administration of amphetamine in female and male rats. Psychopharmacology 155:278–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley PM, Aceto MD, Cook CD, Bowman ER, Newman JL, Harris LS (2004) Discriminative stimulus, reinforcing, physical dependence, and antinociceptive effects of oxycodone in mice, rats, and rhesus monkeys. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 12:163–172. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.3.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr KD (2002) Augmentation of drug reward by chronic food restriction: behavioral evidence and underlying mechanisms. Physiol Behav 76:353–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Campbell UC, Heideman P (2001) Ketoconazole suppresses food restriction-induced increases in heroin self-administration in rats: sex differences. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 9:307–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Morgan AD, Lynch WJ, Campbell UC, Dess NK (2002) Intravenous cocaine and heroin self-administration in rats selectively bred for differential saccharin intake: phenotype and sex differences. Psychopharmacology 161:304–313. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1030-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartoff EH, McHugh RK (2016) Translational studies of sex differences in sensitivity to opioid addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 41: 383–384. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, Aylward SC, Meyer ER (2003) Gender differences in the intravenous self-administration of mu opiate agonists. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 74:541–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins D, Reed B, Zhang Y, Kreek MJ (2016) Sex differences in responsiveness to the prescription opioid oxycodone in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 148:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT (2016) Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med 374:154–163. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1508490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft RM (2008) Sex differences in analgesic, reinforcing, discriminative, and motoric effects of opioids. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 16:376–385. doi: 10.1037/a0012931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft RM, Clark JL, Hart SP, Pinckney MK (2006) Sex differences in locomotor effects of morphine in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 85:850–858. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft RM, Kalivas PW, Stratmann JA (1996) Sex differences in discriminative stimulus effects of morphine in the rat. Behav Pharmacol 7:764–778 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft RM, Stratmann JA, Bartok RE, Walpole TI, King SJ (1999) Sex differences in development of morphine tolerance and dependence in the rat. Psychopharmacology 143:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis KS, Davis LM, Johnson AL, Therrien KL, Contreras RJ (2004) Sex differences in behavioral taste responses to and ingestion of sucrose and NaCl solutions by rats. Physiol Behav 80:657–664. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2003.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsing N, Greaves L, Poole N, Schmidt R (2016) Misuse of prescription opioid medication among women: a scoping review. Pain Res Manag 2016:1754195. doi: 10.1155/2016/1754195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Avila CA, Rounsaville BJ, Kranzler HR (2004) Opioid-, cannabis- and alcohol-dependent women show more rapid progression to substance abuse treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend 74:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubscher CH, Brooks DL, Johnson JR (2005) A quantitative method for assessing stages of the rat estrous cycle. Biotech Histochem 80:79–87. doi: 10.1080/10520290500138422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimishima A, Umihara H, Mizoguchi A, Yokoshima S, Fukuyama T (2014) Synthesis of (−)-oxycodone. Org Lett 16:6244–6247. doi: 10.1021/ol503175n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF (1992) Drugs of abuse: anatomy, pharmacology and function of reward pathways. Trends Pharmacol Sci 13:177–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Shepard JD, Hall FS, Shaham Y (2003) Effect of environmental stressors on opiate and psychostimulant reinforcement, reinstatement and discrimination in rats: a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 27:457–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ, Carroll ME (1999) Sex differences in the acquisition of intravenously self-administered cocaine and heroin in rats. Psychopharmacology 144:77–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Devito EE, Dodd D, Carroll KM, Potter JS, Greenfield SF, Connery HS, Weiss RD (2013) Gender differences in a clinical trial for prescription opioid dependence. J Subst Abus Treat 45:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olkkola KT, Kontinen VK, Saari TI, Kalso EA (2013) Does the pharmacology of oxycodone justify its increasing use as an analgesic? Trends Pharmacol Sci 34:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Deminiere JM, Le Moal M, Simon H (1989) Factors that predict individual vulnerability to amphetamine self-administration. Science 245:1511–1513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Deroche-Gamonent V, Rouge-Pont F, Le Moal M (2000) Vertical shifts in self-administration dose-response functions predict a drug-vulnerable phenotype predisposed to addiction. J Neurosci 20:4226–4232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pravetoni M, Le Naour M, Harmon TM, Tucker AM, Portoghese PS, Pentel PR (2012) An oxycodone conjugate vaccine elicits drug-specific antibodies that reduce oxycodone distribution to brain and hot-plate analgesia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 341:225–232. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.189506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pravetoni M, Pentel PR, Potter DN, Chartoff EH, Tally L, LeSage MG (2014) Effects of an oxycodone conjugate vaccine on oxycodone self-administration and oxycodone-induced brain gene expression in rats. PLoS One 9:e101807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl MD, Boisvert M, Guan Z, Fang J, Grigson PS (2013) A novel model of chronic sleep restriction reveals an increase in the perceived incentive reward value of cocaine in high drug-taking rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 109:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell SE, Rachlin AB, Smith KL, Muschamp J, Berry L, Zhao Z, Chartoff EH (2014) Sex differences in sensitivity to the depressive-like effects of the kappa opioid receptor agonist U-50488 in rats. Biol Psychiatry 76: 213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.07.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclafani A, Hertwig H, Vigorito M, Feigin MB (1987) Sex differences in polysaccharide and sugar preferences in rats. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 11:241–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni-Wastila L, Ritter G, Strickler G (2004) Gender and other factors associated with the nonmedical use of abusable prescription drugs. Subst Use Misuse 39:1–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderberg Lofdal KC, Andersson ML, Gustafsson LL (2013) Cytochrome P450-mediated changes in oxycodone pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics and their clinical implications. Drugs 73:533–543. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0036-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J, Woodside B, Shaham Y (1996) Ovarian hormones do not affect the initiation and maintenance of intravenous self-administration of heroin in the female rat. Psychobiology 24:154–159 [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen M, and Caine SB (2005) Chronic intravenous drug self-administration in rats and mice. Curr Protoc Neurosci Chapter 9, Unit 9 20. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0920s32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenstein ES, Kakolewski JW, Cox VC (1967) Sex differences in taste preference for glucose and saccharin solutions. Science 156:942–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hest A, van Haaren F, van de Poll NE (1989) Perseverative responding in male and female Wistar rats: effects of gonadal hormones. Horm Behav 23:57–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Weele CM, Porter-Stransky KA, Mabrouk OS, Lovic V, Singer BF, Kennedy RT, Aragona BJ (2014) Rapid dopamine transmission within the nucleus accumbens: dramatic difference between morphine and oxycodone delivery. Eur J Neurosci 40:3041–3054. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade CL, Vendruscolo LF, Schlosburg JE, Hernandez DO, Koob GF (2015) Compulsive-like responding for opioid analgesics in rats with extended access. Neuropsychopharmacology 40:421–428. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker QD, Rooney MB, Wightman RM, Kuhn CM (2000) Dopamine release and uptake are greater in female than male rat striatum as measured by fast cyclic voltammetry. Neuroscience 95:1061–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacny JP, Drum M (2010) Psychopharmacological effects of oxycodone in healthy volunteers: roles of alcohol-drinking status and sex. Drug Alcohol Depend 107:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan B, Ma HY, Wang JL, Liu CB (2015) Sex differences in morphine-induced behavioral sensitization and social behaviors in ICR mice. Dongwuxue Yanjiu 36:103–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Mayer-Blackwell B, Schlussman SD, Randesi M, Butelman ER, Ho A, Ott J, Kreek MJ (2014) Extended access oxycodone self-administration and neurotransmitter receptor gene expression in the dorsal striatum of adult C57BL/6 J mice. Psychopharmacology 231:1277–1287. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3306-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Ghee SM, See RE, Reichel CM (2015) Oxytocin differentially affects sucrose taking and seeking in male and female rats. Behav Brain Res 283:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.01.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]