Abstract

The sox2 expressing (sox2+) progenitors in adult mammalian inner ear lose the capacity to regenerate while progenitors in the zebrafish lateral line are able to proliferate and regenerate damaged HCs throughout lifetime. To mimic the HC damage in mammals, we have established a zebrafish severe injury model to eliminate both progenitors and HCs. The atoh1a expressing (atoh1a+) HC precursors were the main population that survived post severe injury, and gained sox2 expression to initiate progenitor regeneration. In response to severe injury, yap was activated to upregulate lin28a transcription. Severe-injury-induced progenitor regeneration was disabled in lin28a or yap mutants. In contrary, overexpression of lin28a initiated the recovery of sox2+ progenitors. Mechanistically, microRNA let7 acted downstream of lin28a to activate Wnt pathway for promoting regeneration. Our findings that lin28a is necessary and sufficient to regenerate the exhausted sox2+ progenitors shed light on restoration of progenitors to initiate HC regeneration in mammals.

Research organism: Zebrafish

Introduction

The auditory epithelium is a delicate structure located in the cochlea that is composed of sensory hair cells (HCs) and nonsensory support cells (SCs). During early development of mouse cochlea, the transcription factor sox2 is required to determine the prosensory region that mainly contains progenitors (Julian et al., 2013; Kiernan et al., 2005; Dabdoub et al., 2008). From E12.5 to E14.5 sox2+ progenitors exit cell cycle and differentiate into auditory HCs and SCs. Basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor atoh1 acts as the cardinal gene initiating auditory HC differentiation since atoh1 deficiency causes complete loss of cochlear HCs (Bermingham et al., 1999). A subset of post-mitotic progenitors start to express high levels of atoh1 and downregulate sox2 expression to differentiate into the HC precursors (Dabdoub et al., 2008; Zhong et al., 2019; Cai and Groves, 2015; Zhang et al., 2017). Afterwards, their terminal differentiation toward mature HCs is promoted by the upregulation of atoh1 target genes, such as pou4f3 (Cai et al., 2015). In the meanwhile, differentiating HCs secret Notch ligands to activate Notch pathway, which inhibits atoh1 expression in neighboring cells and forces them to adopt the SC fate (Abdolazimi et al., 2016; Costa et al., 2017; Lanford et al., 1999).

The zebrafish lateral line is a mechanosensory organ composed of a series of neuromasts distributed on the body surface for detecting water flow. The lateral line HCs share similarities with their counterparts in mammalian inner ear in morphology, function and developmental pathways (Whitfield, 2002; Nicolson, 2005). Each neuromast contains sensory HCs in the center surrounded by SCs and mantle cells (MCs). Aminoglycoside antibiotics, such as neomycin, ablates mature HCs and initiates robust mitotic regeneration that is characterized with SC division and differentiation (Harris et al., 2003; Jiang et al., 2014; Williams and Holder, 2000; Ma et al., 2008; Romero-Carvajal et al., 2015). The powerful capacity to regenerate HCs sustains after multiple rounds of damage, and retains throughout lifetime (Cruz et al., 2015; Pinto-Teixeira et al., 2015). Even after severe loss of the tissue integrity, the residual SCs have high potential to recover the neuromast by acting plastic to generate all three cell types (Viader-Llargués et al., 2018). Like in inner ear, atoh1a is expressed in HC precursors but not mature HCs in neuromast while sox2 is expressed in a part of SCs and MCs (Ma et al., 2008; Lush et al., 2019). Sox2+ SCs behave as progenitors to proliferate and differentiate through activation of canonical Wnt pathway during regeneration (Hernández et al., 2007; Jacques et al., 2014). However, it is unknown how regeneration is initiated when sox2+ progenitors are absent.

Mammalian sensory HCs are vulnerable to damages caused by antibiotics, chemotherapeutical drugs and noise, which results in various hearing and balance diseases (Cox et al., 2014). Until now, the principal method used to initiate auditory HC regeneration in mammalian inner ear is to induce the transdifferentiation of SCs into HCs by upregulating atoh1 expression. For example, many studies tried to overexpress atoh1 in SCs with adenovirus, or used Notch inhibitor to increase atoh1 expression (Atkinson et al., 2018; Mizutari et al., 2013; Izumikawa et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2012). However, because the efficiency of HC induction is very low and SCs are lost due to transdifferentiation, very limited progress toward hearing recovery has been achieved (Cox et al., 2014; Zheng and Zuo, 2017; Chen et al., 2019). New strategies of restoring sox2+ progenitors to initiate mitotic regeneration would be more promising to realize functional regeneration in mammalian adult inner ear. Unfortunately, very little is known whether and how sox2+ progenitors can be restored in sensory epithelium.

Here in the zebrafish lateral line, we found that exhausted sox2+ progenitors were able to restore quickly for initiating HC regeneration in severe injury. Atoh1a+ HC precursors were the main population that survived post severe injury and dedifferentiated into sox2+ progenitors through yap-lin28a pathway.

Results

Exhausted sox2+ progenitors were quickly recovered by intensive proliferation post severe injury

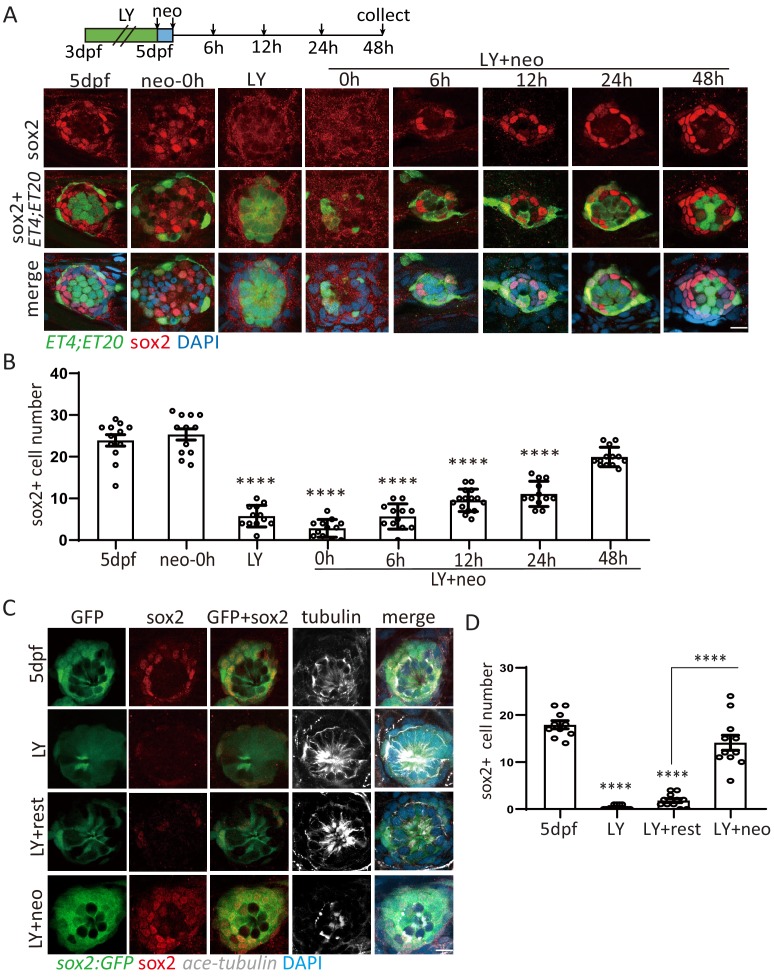

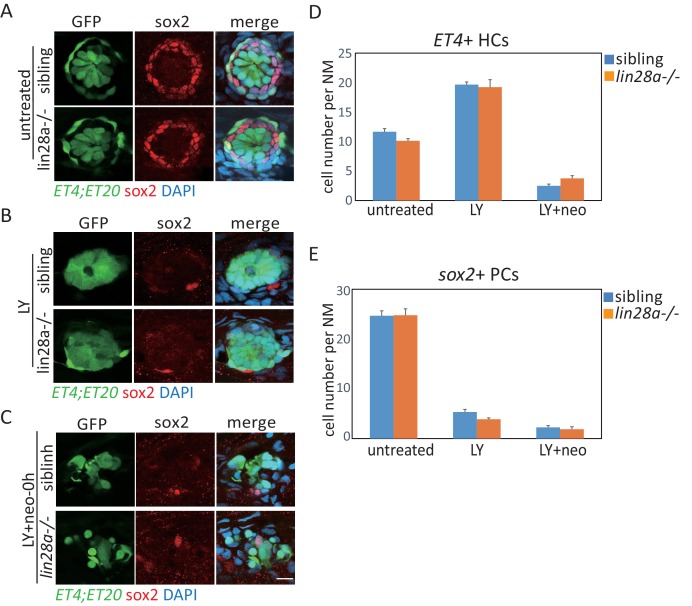

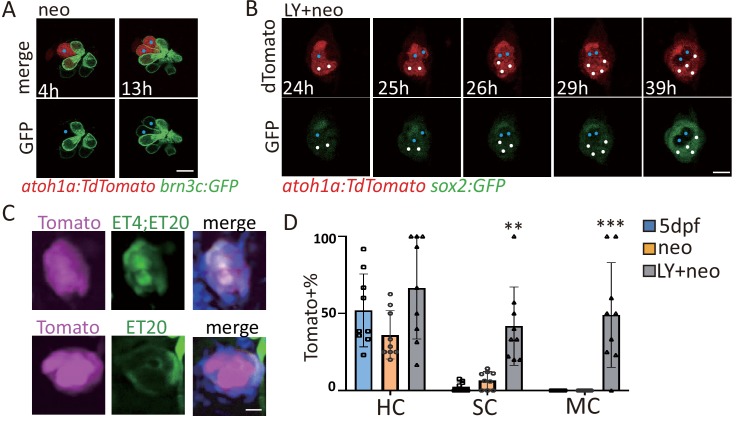

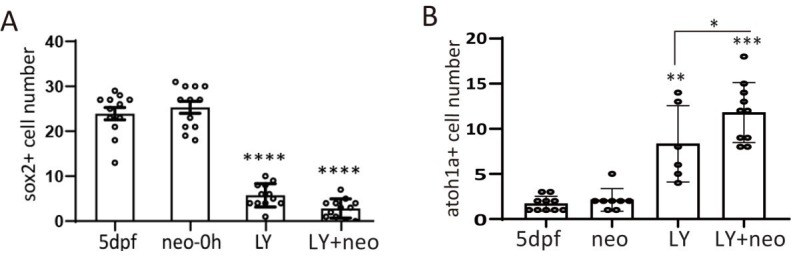

It is well documented that Notch signaling pathway negatively regulates the differentiation of SCs into HCs (Ma et al., 2008; Haddon et al., 1998). Using the γ-secretase inhibitor LY411575 to inhibit Notch pathway from 3-day-post-fertilization (dpf) to 5dpf, we found that SCs were exhausted by persistent differentiation into HCs (Figure 1—figure supplement 1). Neomycin was used to ablate mature HCs following LY treatment (LY+neo), which leads to the severe injury with both HCs and SCs being ablated. Sox2 marks the proliferative progenitors that produce both SCs and HCs in homeostatic and regenerative neuromasts (Hernández et al., 2007). We analyzed sox2+ cells in neo- and LY+neo-treated neuromast by immunostaining with anti-sox2 antibody. While the distribution of sox2+ cells moved to the center post neo compared with normal larvae, the number was not changed. But sox2+ cell number was dramatically decreased after LY or LY+neo (Figure 1A–B). Surprisingly, sox2+ progenitors were able to recover quickly post LY+neo. A few sox2+ progenitors appeared early at 6 hr, with increased sox2+ progenitors being regenerated afterwards and recovered to normal level by 48 hr. In Figure 1A, ET4+ HCs appeared at 48 hr post LY+neo, suggesting that HC regeneration happened after the recovery of sox2+ progenitors.

Figure 1. Exhausted sox2+ progenitors were able to restore quickly post severe injury.

(A, B) ET4;ET20 larvae were treated with neomycin, LY411575 (3dpf-5dpf), or neomycin following LY (LY+neo), and collected at indicated time points post neomycin treatment for sox2 immunostaining. The number of sox2+ progenitors was not affected post neo, while it was significantly decreased in LY and LY+neo-0h. The sox2+ progenitors were regenerated post LY+neo and recovered to normal level at 48 hr post LY+neo. (C, D) The sox2:GFP reporter was treated with LY from 3dpf to 5dpf to exhaust GFP+ progenitors. GFP+ progenitors cannot be regenerated when resting in normal medium for 2 days post LY treatment (LY+rest). In contrast, sox2+ progenitors were quickly recovered to normal level at 2-day post LY+neo. Scale bar equals 10 μm. All groups are compared with 5dpf unless indicated.

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Severe injury causes damage to HCs, SCs and MCs.

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. More proliferative SCs and MCs were induced post severe injury compared with normal injury.

In addition to sox2 antibody staining, we also used sox2-2a-GFP knock-in reporter (sox2:GFP) (Shin et al., 2014) to observe the recovery of sox2+ progenitors. GFP-positive cells in neuromast, which were mostly co-labeled by sox2 antibody, were significantly decreased in LY, and recovered to normal level at 48 hr post LY+neo. In contrast, the exhausted sox2+ progenitors were not recovered without severe injury (Figure 1C–D). These results indicate that sox2+ progenitors in the zebrafish lateral line have high potential to regenerate themselves when exhausted by severe injury.

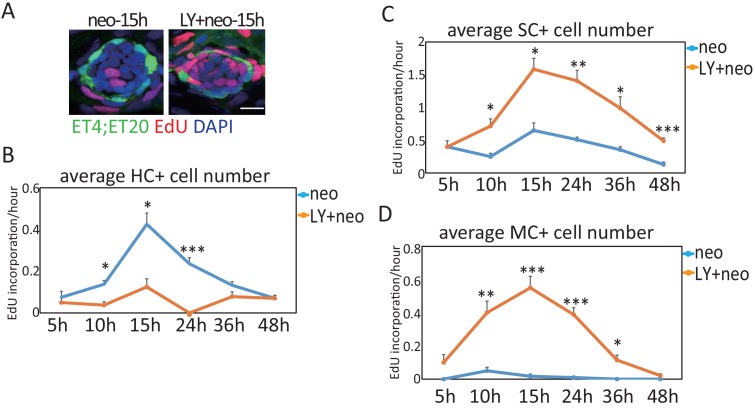

During regeneration, three types of cell divisions can be detected by combining EdU staining with GFP expression in ET4;ET20 (Romero-Carvajal et al., 2015). First, EdU is incorporated in differentiating cells when one HC precursor divides into two HCs (ET4+EdU+, or HC+). The second type is SC proliferation in which one SC divides into two SCs (ET4-ET20-EdU+, or SC+). The third type is mantle cell (MC) proliferation in which one MC divides into two MCs (ET20+EdU+, or MC+). Our results showed that proliferation in SCs or MCs post severe injury is highly increased compared with neo-induced normal injury, while HC differentiation is decreased (Figure 1—figure supplement 2). By time lapse, we recorded 12 times of MC or SC divisions in one neuromast from 24 hr to 40 hr post LY+neo, but none of them was differentiation (Video 1). These results indicate that intensive proliferation is necessary to accomplish regeneration post severe injury.

Video 1. ET4;ET20;cldnB:H2Amcherry larvae treated with LY+neo were processed for time lapse.

Results showed the intensive cell divisions (CDs) during severe-injury-induced regeneration. Scale bar equals 10 μm.

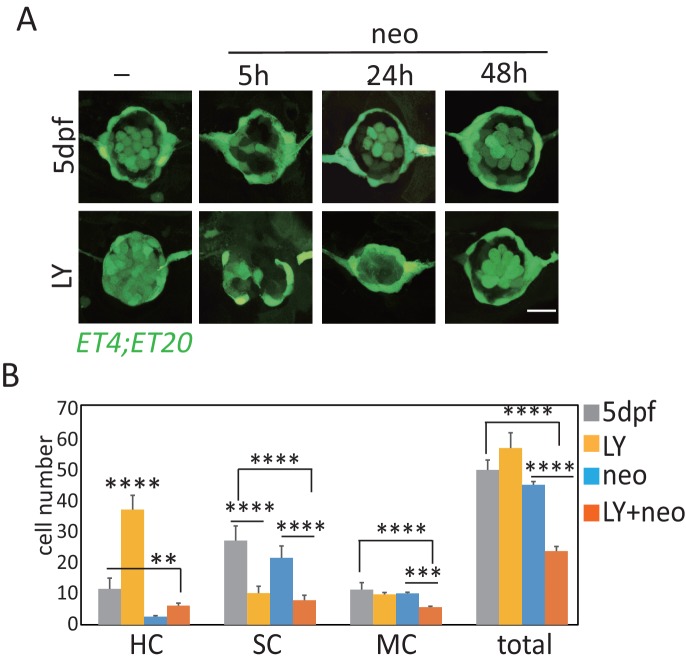

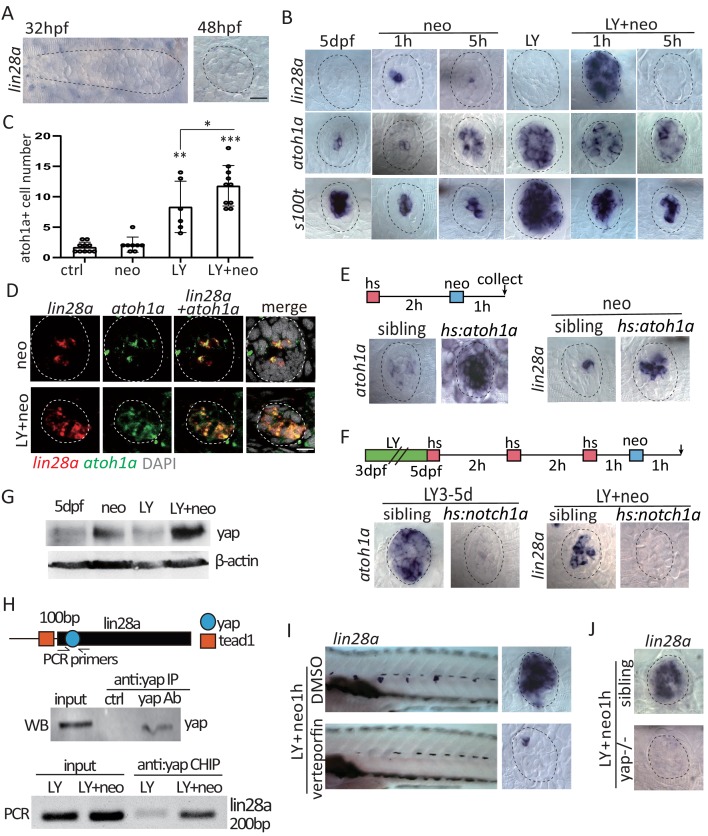

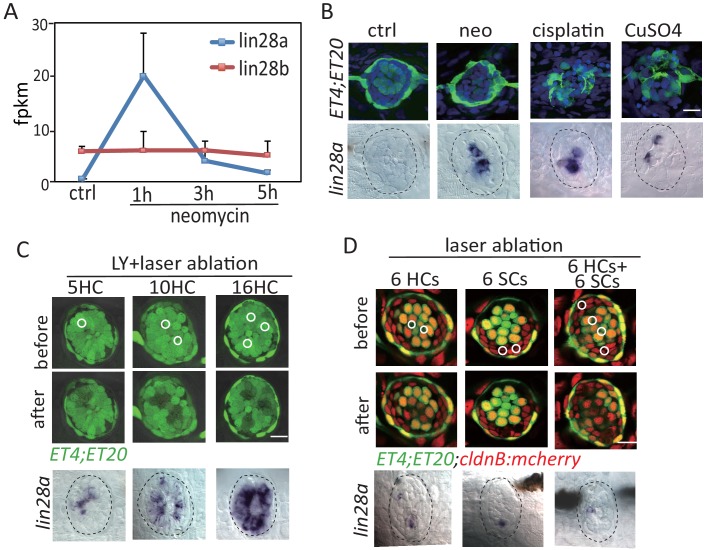

Activated yap upregulated lin28a expression in atoh1a+ HC precursors upon severe injury

We next investigated the mechanism involved in progenitor recovery. Previously, we have collected samples of regenerating neuromasts for RNA-Seq analysis (Jiang et al., 2014) and identified that lin28a was transiently upregulated post neomycin treatment (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A). By in situ hybridization, we verified that lin28a was not expressed in the developing lateral line primordium or neuromast (Figure 2A). Neomycin treatment and other types of HC injuries, including heavy metal (copper sulfate) or chemotherapeutic drug (cisplatin), induced sporadic lin28a expression (Figure 2—figure supplement 1B). Interestingly, LY+neo induced much higher expression of lin28a compared with neo alone (Figure 2B). Since LY+neo induced more cell death than neo as illustrated by ablation of s100t expressing HCs, we tested whether lin28a induction is proportional to the injury size. We used laser ablation to manipulate the number of injured cells in LY-treated neuromast. Low level of lin28a was induced when five HCs were ablated while higher level of lin28a was observed when sixteen HCs were ablated. Furthermore, we found that the ablation of SCs could also induce lin28a expression (Figure 2—figure supplement 1C–D).

Figure 2. Activated yap upregulate lin28a transcription in atoh1a+ HC precursors post severe injury.

(A) Lin28a was not expressed in the developing lateral line primordium or neuromast. (B) Treatment with Notch inhibitor LY411575 from 3dpf to 5dpf increased expression atoh1a and s100t. More lin28a expression was observed in LY+neo-1h compared with neo-1h. No lin28a was detected at 5 hr post LY+neo or neo. (C) The number of atoh1a-transcribed cells detected by in situ were higher at 1 hr post LY+neo compared with LY. (D) Double fluorescent in situ showed that lin28a was co-expressed with atoh1a post neo or LY+neo. (E) Induction of lin28a post injury was increased when atoh1a was overexpressed in hs:atoh1a. (F) Lin28a expression was completely blocked when atoh1a was inhibited in hs:notch1a. (G) Western blot results showed that LY+neo induced higher yap expression compared with neo alone. (H) Motifs of yap and tead1 (co-transcriptional factor of yap) binding sites were predicted near lin28a transcriptional start site. CHIP-PCR results verified that yap directly binds the predicted motif. (I and J) Inhibition of yap using verteporfin or yap mutant blocked lin28a induction post LY+neo. Scale bar equals 10 μm.

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. lin28a was induced by various kinds of injury and lin28a expression level was proportional to injury size.

Figure 2—figure supplement 2. Yap was activated immediately post LY+neo.

Atoh1a is a master gene for HC specification and labels mostly HC precursors including differentiating HCs and young HCs (Cai and Groves, 2015; Lush et al., 2019). We noticed that atoh1a+HC precursors were the main population that survived post LY+neo (Figure 2C). Using double fluorescent in situ, it was verified that lin28a was induced in atoh1a+ HC precursors in both neo- and LY+neo-treated neuromasts (Figure 2D). We further assessed the effect of atoh1a expression on lin28a induction. We used hs:atoh1a to induce atoh1a expression after heat shock and found that neo-induced lin28a was increased (Figure 2E). In contrast, lin28a induction post LY+neo was completely blocked when atoh1a expression was inhibited in hs:notch1a (Figure 2F). All these results indicate that lin28a was induced in atoh1a+ HC precursors post injury.

We further analyzed the upstream pathway that induce lin28a post injury. It’s documented that Wnt activation regulates lin28a expression (Yao et al., 2016), so we first examined whether Wnt activation acts upstream to induce lin28a expression post injury. We used hs:dkk1 to inhibit Wnt activation and found that lin28a induction post injury was not affected (Figure 2—figure supplement 2A). Because Hippo pathway critically regulates regeneration of many tissues (Gregorieff et al., 2015; Gregorieff and Wrana, 2017; Moya and Halder, 2016), we therefore tested the expression of yap and taz, two cardinal mediators of Hippo pathway. We found the protein levels of yap was up-regulated at 1 hr post LY+neo while taz was increased until 5 hr (Figure 2G and Figure 2—figure supplement 2B). By immunostaining, more yap was also dectected in LY+neo-treated neuromast cells compared with neo. Yap expression was inhibited when atoh1a is inhibited with hs:notch1a, which suggests that yap is activated in atoh1a+ HC precursors (Figure 2—figure supplement 2D–G). Expressions of the classic yap target genes, such as cyr61 and ctgfa, and the Hippo pathway genes, such as yap and mst2, were dramatically increased post LY+neo (Figure 2—figure supplement 2H–I), which was blocked with verteporfin (an inhibitor of yap-mediated transcription by blocking yap-tead1 interaction).

Interesting we found a conserved yap binding motif located at 100 bp downstream of lin28a transcription start site, where a tead1 binding motif is located nearby. We used CHIP-PCR to verify that yap directly binds to this region of lin28a promoter post severe injury (Figure 2H). In addition, LY+neo-induced lin28a expression was blocked in verteporfin or in yap mutant (Figure 2I–J). Taken together, we found that yap is highly activated by severe injury and directly binds lin28a promoter to initiate its transcription in atoh1a+ HC precursors.

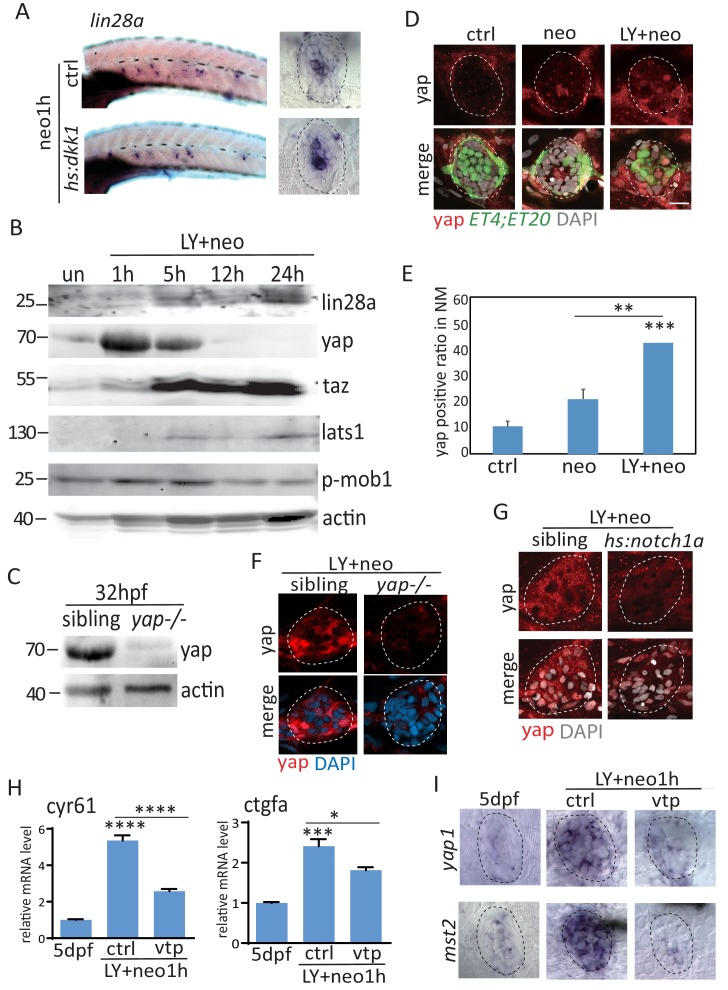

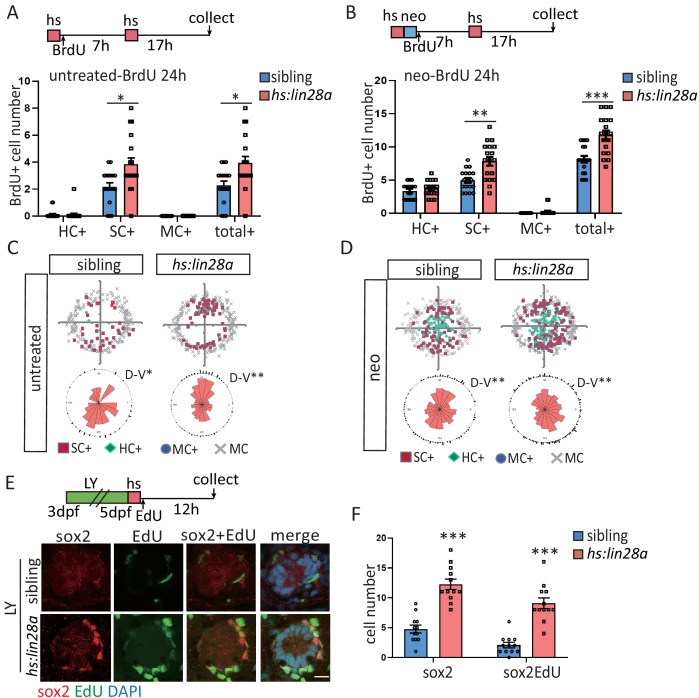

Yap-lin28a pathway is necessary and sufficient to promote progenitor recovery

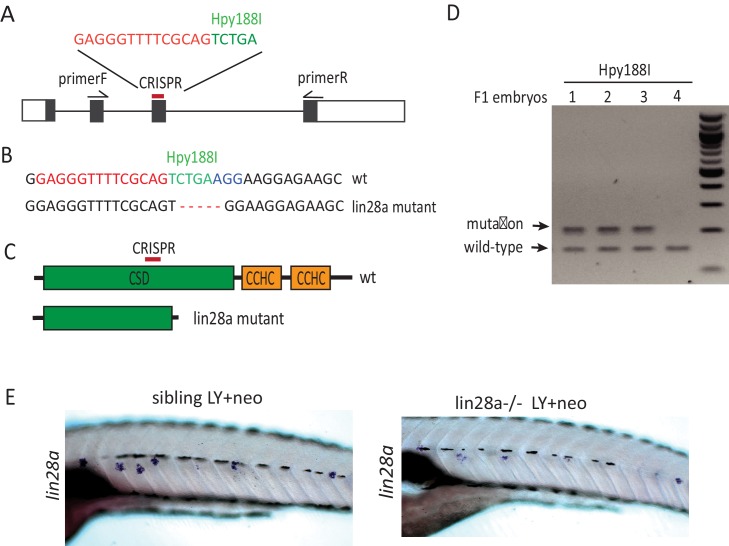

To determine whether lin28a is required for HC regeneration, we generated a lin28a mutant allele (lin28a^psi37, referred to as lin28a-) that harbors a deletion of five nucleotides and causes a premature stop codon within the cold shock domain (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). We found that lin28a deficiency had no effect on HC or SC number in homeostasis, nor did it affect exhaustion of sox2+ progenitors post LY or LY+neo (Figure 3—figure supplement 2). Since LY+neo treatment substantially enhanced lin28a expression, we examined whether lin28a deficiency affected LY+neo-induced regeneration. We found that the regenerated HC number was decreased by lin28a deficiency (Figure 3A). In addition, the number of regenerated SCs (Figure 3A) and the proliferative SCs (Figure 3B) were both significantly decreased. The EdU-positive SC cells that were located in each quadrant with no polarization in sibling post LY+neo were almost cleared in lin28a mutant (Figure 3C–D). In contrast, the EdU-positive SC number post neo is not affected by lin28a deficiency (Figure 3E), indicating that lin28a is not required for neo-induced regeneration.

Figure 3. Yap-lin28a pathway is essentially required for progenitor recovery post severe injury.

(A) The number of SCs and total cells were counted at 48 hr post LY+neo and were significantly decreased in lin28a mutant compared with sibling. (B–E) The ET4;ET20 larvae were incorporated with EdU post neo or LY+neo treatment. Three populations labeled with ET4+EdU+ (HC+), ET20+EdU+ (MC+) or ET4-ET20-EdU+ (SC+) were counted and recorded with location information. The proliferative SCs post LY+neo were significantly decreased in lin28a mutant compared with sibling (B and C), while not changed in neo-induced regeneration (E). (D) EdU plots show the positions of EdU+ nuclei of 18 neuromasts superimposed on the same plane, and rose diagrams document the angular positions of SC+. The results show that the proliferative SCs are evenly distributed in each quadrant with no polarization post LY+neo. (F) LY+neo-induced Edu incorporation was significantly reduced in yap mutant. (G) The hs:lin28a larvae were heat-shocked and pre-treated with 10 μM verteporfin before adding neomycin. Samples were collected at 14 hr post LY+neo for EdU+ cell counting. Proliferation (SC+) is significantly decreased post LY+neo in verteporfin, which could be rescued by overexpression of lin28a with hs:lin28a. (H, I) The numbers of regenerated sox2+ progenitors (sox2) and proliferative progenitors (sox2EdU) post LY+neo were both reced in lin28a mutant. Scale bar equals 10 μm.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Create lin28a mutant using CRISPR.

Figure 3—figure supplement 2. HCs and sox2+ progenitors were not affected by lin28a deficiency in homeostasis, LY and LY+neo.

We also observed that yap deficiency induced similar phenotype with lin28a mutant. Yap mutation or inhibition with verteporfin caused proliferative deficiency post LY+neo, but has no effect on SC proliferation post neo (Figure 3F–G and data not shown). We have generated a transgenic line in which heat shock promoter is used to drive lin28a expression. Proliferative deficiency in verterporfin was rescued by hs:lin28a (Figure 3G), indicating that lin28a acts downstream of yap to promote SC proliferation. We next examined whether lin28a is required for recovery of sox2+ progenitors post LY+neo. The number of proliferative and regenerated progenitors at 12 hr post injury were significantly reduced in lin28a mutant (Figure 3H–I).

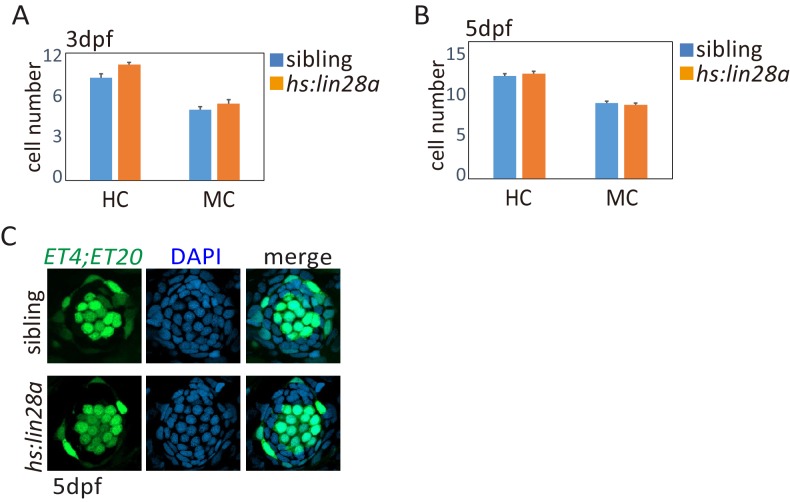

We found that the HC number was not changed in hs:lin28a, indicating that lin28a has no effect on HC development (Figure 4—figure supplement 1). We next examined whether lin28a overexpression is sufficient to promote progenitor proliferation. The number of proliferative SCs was significantly increased when lin28a is overexpressed in both homeostatic and neo-treated neuromast, whereas HC differentiation was not changed (Figure 4A–B). The proliferative SCs are localized in dorsal and ventral poles of neuromast in homeostasis and neo-induced regeneration (Ma et al., 2008; Romero-Carvajal et al., 2015; Wibowo et al., 2011). The location of proliferative SCs still remain polarized in hs:lin28a (Figure 4C–D). We further examined whether lin28a overexpression is sufficient to induce sox2+ progenitors, and observed higher number of proliferative progenitors in hs:lin28a post LY (Figure 4E–F).

Figure 4. Overexpression of lin28a is sufficient to restore the exhausted progenitors.

(A–D) ET4;ET20;hs:lin28a larvae were incorporated with BrdU for 24 hr following heat-shock and/or neomycin treatment. (A, B) Overexpression of lin28a increased number of proliferative SCs (SC+) in both untreated and neomycin conditions. (C, D) BrdU plots and rose diagrams indicate that locations of SC+ still remain dorsally and ventrally polarized in hs:lin28a. (E, F) OverexpressUion of lin28a is sufficient to partially restore the exhausted sox2+ progenitors post LY. Scale bar equals 10 μm.

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Developing HCs and MCs were not affected in hs:lin28a.

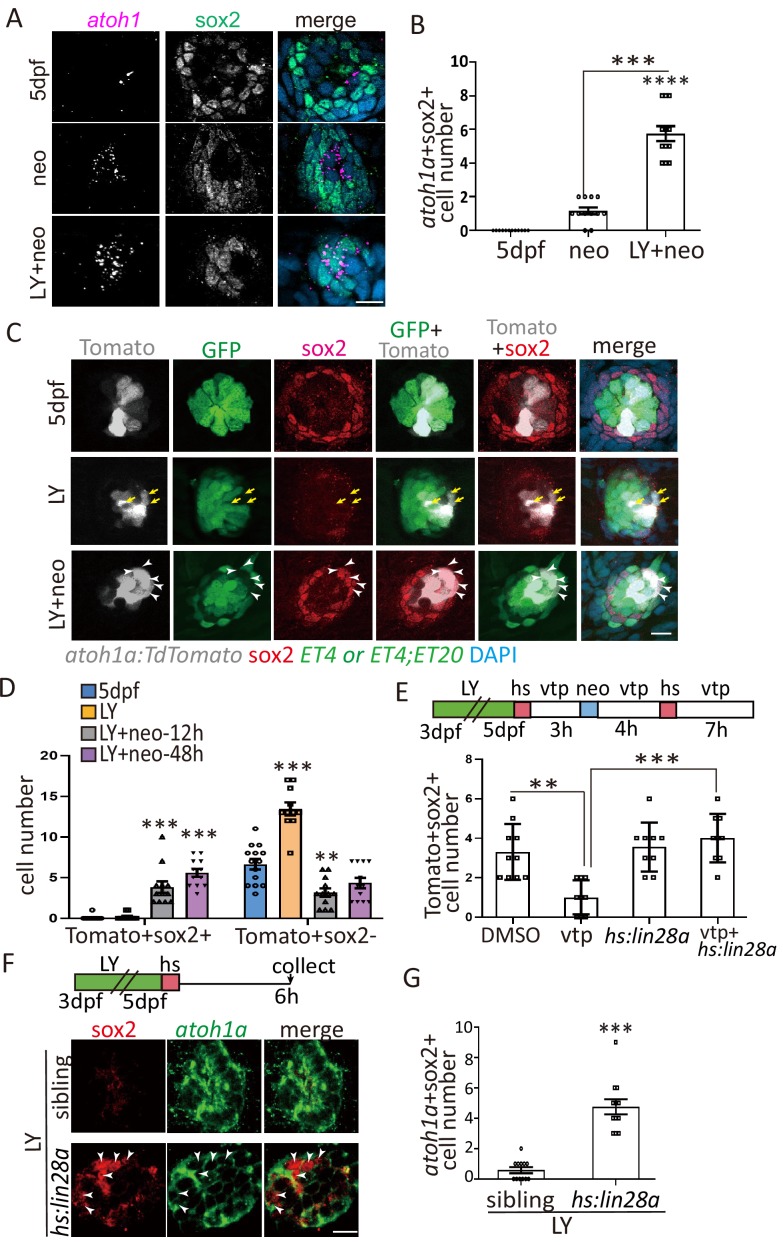

Atoh1a+ HC precursors gained sox2 expression through Yap-lin28a pathway

Our data indicate that lin28a is induced in atoh1a+ HC precursors post injury, but lin28a functions to recover sox2+ progenitors during regeneration. To address this paradox, we hypothesized that HC precursors gained sox2 expression to initiate regeneration post severe injury. We co-labeled the expressions of atoh1a mRNA and sox2 protein and found that the number of atoh1a+sox2+ cells in LY+neo was significantly increased compared with neo (Figure 5A–B). In addition, we used atoh1a:TdTomato reporter to test whether atoh1a+ cells expressed sox2 post severe injury. The atoh1a:TdTomato reporter labeled partially ET4-positive HCs (Figue 5C, ctrl) and also a few cells that are ET4 negative and sox2 negative which are likely HC precursors (Figure 5C, yellow arrows in LY). Very few Tomato+ cells express sox2 in normal or LY-treated larvae. However, significantly more Tomato+ cells turned on sox2 expression at 12 hr and 48 hr post LY+neo and become Tomato+sox2+ cells (Figure 5D). We further used time-lapse microscopy to trace atoh1a:TdTomato cells and found that the Tomato+ cells became HCs in both neo and LY+neo (blue dots in Figure 5—figure supplement 1A–B, Video 2 and S3). However, it’s only in LY+neo-induced severe injury that Tomato+ cells became sox2-positive cells labeled by sox2:GFP (white dots in Figure 5—figure supplement 1B and Video 3). We traced the Tomato+ cells for their fate becoming HCs, SCs or MCs (Figure 5—figure supplement 1C–D), and the results showed that significantly higher ratio of SCs were labeled by Tomato post LY+neo. More importantly many Tomato+ MCs were labeled post LY+neo, but none was detected in normal or neo-treated larvae, suggesting that atoh1a+sox2+ cells gained more potential to produce MCs.

Figure 5. Yap-lin28a pathway promotes sox2 expression in atoh1a+ HC precursors.

(A–B) Larvae were stained with sox2 antibody and atoh1a RNA probe at 6 hr post neo or LY+neo treatment. The number of atoh1a+sox2+ cells was significantly increased in LY+neo group. (C–D) The atoh1a:TdTomato larvae were used to trace atoh1a+ HC precursors in ctrl, LY or LY+neo. Results showed that Tomato+ cells labeled partial ET4+ HCs and ET4-sox2- HC precursors (yellow arrows). However, many atoh1a+ cells start to express sox2 from 12 hr post LY+neo and their numbers were significantly increased compared with normal larvae. The arrowheads in (C) pointed the atoh1a+sox2+ cells at 48 hr post LY+neo. (E) The atoh1a:TdTomato;hs:lin28a larvae was treated with LY+neo and verteporfin and collected for immunostaining with sox2 antibody. The cell number of Tomato+sox2+ is decreased in verteporfin and overexpression of lin28a could rescue the phenotype. (F–G) The LY-treated hs:lin28a larvae were heat-shocked to overexpress lin28a. Samples were collected for staining with sox2 antibody and atoh1a RNA probe. The number of atoh1a+sox2+ cells was significantly increased in hs:lin28a group, indicating that lin28a is sufficient to express sox2 in atoh1a+ HC precursors. Scale bar equals 10 μm.

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. Atoh1a+ cells became SCs and MCs post severe injury.

Video 2. The neuromast of atoh1a:TdTomato;brn3c:GFP larvae treated with neo was imaged for time lapse.

Result showed that one Tomato+ cell divided and turned into two GFP+hair cells post neo. Scale bar equals 10 μm.

Video 3. The neuromast of atoh1a:TdTomato;sox2:GFP larvae treated with LY+neo was imaged for time lapse.

One Tomato+ cell (blue dot) divided and turned into two HCs that are GFP negative in the center. The other two Tomato+ cells (white dots) divided and converted into four sox2+ progenitors. Scale bar equals 10 μm.

We further tested whether HC precursors gained sox2 expression through Yap-lin28a pathway. The Yap inhibitor verteporfin decreased Tomato+sox2+ cell number post severe injury, which was rescued by overexpression of lin28a (Figure 5E). Significantly higher number of atoh1a+sox2+ cells were induced in LY-treated hs:lin28a (Figure 5F–G).

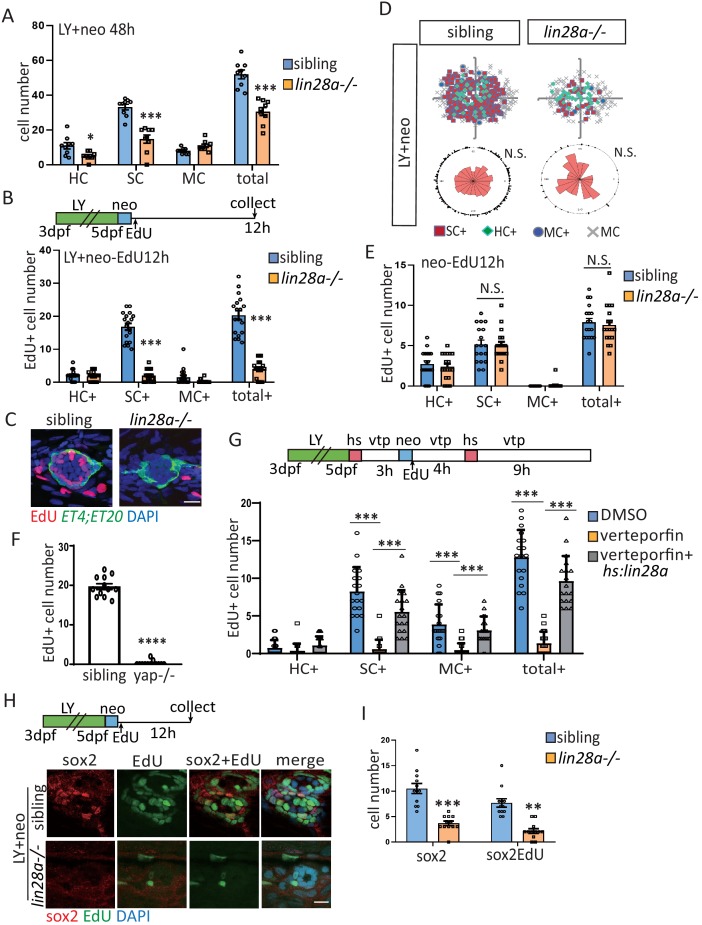

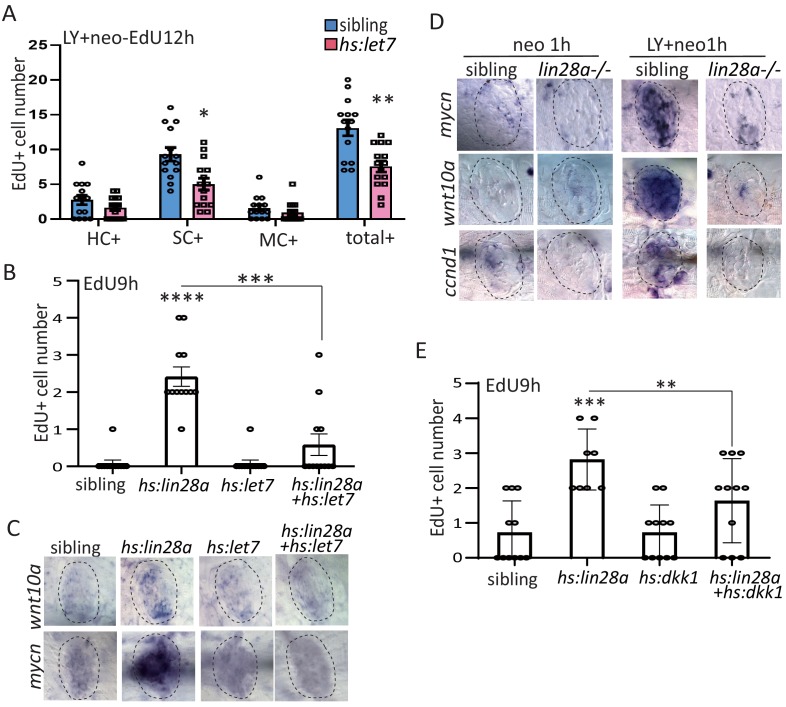

MicroRNA let7 acts downstream of lin28a to activate wnt pathway for promoting regeneration

Lin28a has been described to regulate progenitor proliferation in developing inner ear by inhibiting let7 microRNA processing (Golden et al., 2015). To interrogate the function of let7 microRNA in regenerating lateral line, we have created hs:let7 transgenic line. Similar with lin28a mutant, hs:let7 showed the defect of SC proliferation post LY+neo (Figure 6A). We further found that overexpression of let7 inhibited hs:lin28a-induced proliferation (Figure 6B), indicating that let7 acts downstream of lin28a to promote regeneration.

Figure 6. MicroRNA let7 acts downstream of lin28a to activate Wnt pathway for promoting progenitor regeneration.

(A) We created hs:let7 transgenic line and found that it recapitulates the phenotype of lin28a-/- by decreasing proliferative SCs post LY+neo. (B) The induction of EdU+ proliferative cells was blocked by hs:let7, indicating that let7 microRNA acts downstream of lin28a to induce proliferation. (C) In situ hybridization results showed that expression of Wnt pathway genes, such as wnt10a and mycn, were increased in hs:lin28a. The activation of Wnt pathway genes in hs:lin28a were blocked when let7 was overexpressed, indicating that let7 acts downstream of lin28a to inhibit Wnt pathway. (D) Expressions of Wnt pathway genes, such as mycn, wnt10a and ccnd1 (cyclind1), were highly induced at 1 hr post LY+neo in sibling, but were not detected in lin28a-/-. (E) Inhibition of Wnt pathway with hs:dkk1 decreased lin28a-induced EdU+ proliferative cells, indicating that Wnt activation acts downstream of lin28a to induce regeneration.

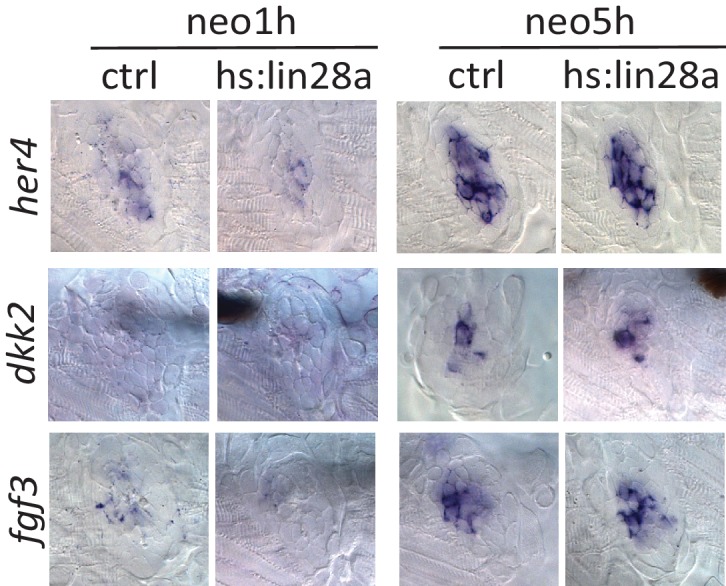

Figure 6—figure supplement 1. Notch and Fgf pathways were not affected by lin28a overexpression.

Lin28a has no effect on Notch and Fgf pathways as her4, a Notch pathway gene, and fgf3, a Fgf pathway gene were not changed in hs:lin28a (Figure 6—figure supplement 1). We then tested whether Wnt pathway acts downstream of lin28a/let7 to promote proliferation. Overexpression of lin28a was sufficient to upregulate Wnt pathway genes wnt10a and mycn, which was inhibited by overexpression of let7 (Figure 6C). Activation of Wnt pathway genes at 1 hr post LY+neo were blocked in lin28a mutant (Figure 6D). We further tested the function of Wnt pathway and found that lin28a-induced proliferation were inhibited by hs:dkk1 in which Wnt activation is blocked (Figure 6E). To summarize, we found that lin28a activates Wnt pathway through let7 for promoting regeneration.

Discussion

The zebrafish lateral line provides a valuable model for studying the mechanism underpinning progenitor regeneration

Progenitors that divide and differentiate to generate HCs in embryonic development are absent in adult mammalian inner ear, which leads to the regeneration failure post injury. In this study, we simulated the situation of progenitor absence in the zebrafish lateral line through persistent conversion of sox2+ progenitors into HCs with Notch inhibitor LY411575. By adding neomycin post LY treatment to ablate HCs, we created a severe injury model in which both HCs and progenitors were eliminated. In big contrast to mammalian inner ear, progenitors in the lateral line were able to quickly restore themselves post severe injury, with HCs being regenerated afterwards. This model provides a valuable tool to elucidate the mechanisms underpinning progenitor recovery for initiating HC regeneration.

Here, we found that yap-lin28a-let7-Wnt axis is essential to promote progenitor regeneration. Lin28a is not only necessary but also sufficient to induce progenitor recovery. Our findings elucidate the underlying mechanism of progenitor regeneration, and open a novel avenue of restoring progenitors to enhance mammalian HC regeneration.

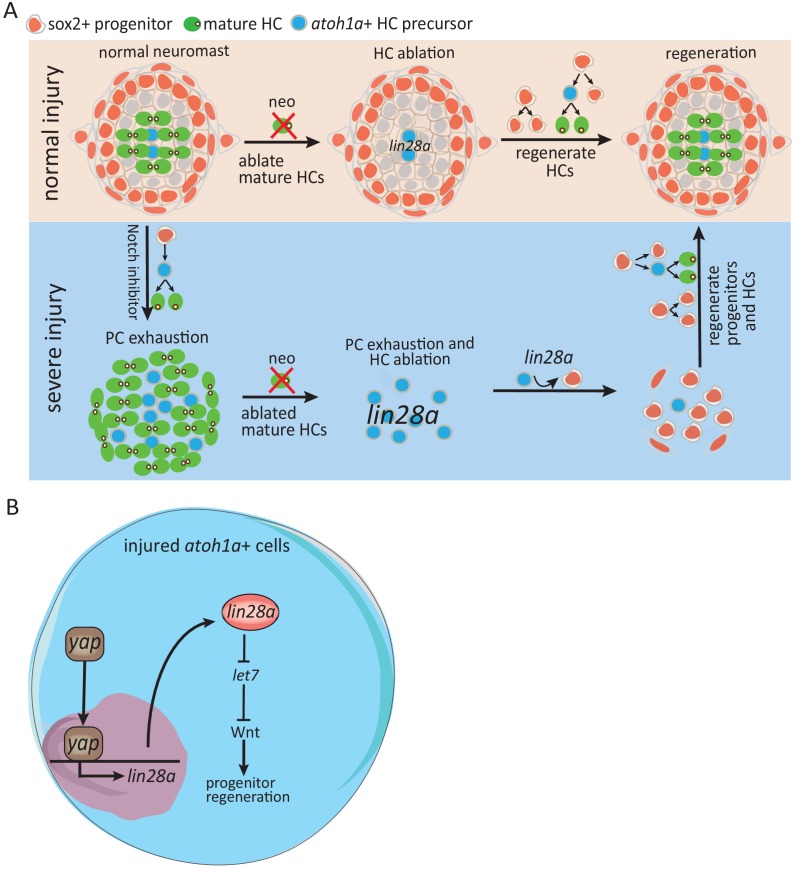

In contrast to the situation of severe injury, our data showed that yap inhibition or lin28a deficiency has no effect on progenitor proliferation post neo (Figure 3E and data not shown). Wnt pathway, which acts downstream of lin28a, is required to induce progenitor proliferation. We found that Wnt pathway was highly activated immediately post severe injury, but was not activated at 1 hr post neo. Since the number of sox2+ progenitors were not reduced post neo, it seems not necessary to activate Wnt for producing more progenitors. Therefore, our results identified that Yap-lin28a pathway functions specifically in severe-injury induced regeneration for promoting progenitor recovery (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Schematic model illustrates how Yap-lin28a pathway regulates progenitor regeneration post severe injury.

(A) It’s known that sox2+ progenitors that are preserved post neo-induced HC injury divide and differentiate to regenerate HCs. To simulate the situation in mammalian inner ear where the progenitors are absent, we created a severe injury model by exhausting sox2+ progenitors with Notch inhibitor and ablating mature HCs with neomycin. We found that the exhausted sox2+ progenitors in severe injury have high potential to restore themselves within 48 hr, with HCs being regenerated afterwards. The atoh1a+ HC precursors, the main population that survived post severe injury, were converted into proliferative progenitors to initiate regeneration through yap-lin28a pathway. (B) Yap is activated in atoh1a+ HC precursors post severe injury and binds directly to lin28a promoter for initiating its transcription. Lin28a activates Wnt pathway through microRNA let7 to promote regenerative proliferation.

The upstream signal that activates yap post injury

Previous studies have described yap as an important regulator in mediating regeneration (Gregorieff and Wrana, 2017; Moya and Halder, 2016), but the downstream mechanism is unclear. Here, in this paper, we prove that severe injury activated yap directly binds lin28a promoter for transcriptional initiation. Lin28a acts downstream of yap to regulate progenitor regeneration.

The mechanism of yap activation post severe injury remains elusive. It is hypothesized that either injured cells secrete diffusible molecules leading to widespread yap activation, or the damage of cell junction adjacent to the injury site activates yap (Moya and Halder, 2016). We observed lin28a induction after laser ablation of HCs in the restricted areas. Our results showed that the lin28a-expressing cells were very close to the damaged HCs (Figure 2—figure supplement 1C), suggesting that the damage of cell junction might lead to yap-lin28a activation. In addition, we have noticed that not only HC injury but also the ablation of SCs was able to induce lin28a (Figure 2—figure supplement 1D), indicating that the injury of either HCs or SCs triggers yap-lin28a activation. Since cell-junction-associated protein amotl2a has been reported restricting yap activity in the zebrafish lateral line primordium (Agarwala et al., 2015), it is possible that the loss of amotl2a post HC injury might result in yap activation. This assumption requires further investigation.

The cellular mechanism mediated by Yap-lin28a pathway that regulates progenitor regeneration

It was reported that lin28b-let7 functions to enhance progenitor proliferation during embryonic inner ear development (Golden et al., 2015), but the downstream pathway is still unknown. Our data showed that lin28a-let7 functions to promote progenitor proliferation during regeneration, which is consistent with the previous finding that lin28a regulates retinal regeneration through let7 (Ramachandran et al., 2010). Our results indicate that Wnt pathway acts downstream of lin28a-let7 for promoting progenitor regeneration. Hippo and Wnt pathway genes, such as yap1, wnt10a, mycn, cyclind1, were highly induced by Yap-lin28a post severe injury. During early development the lateral line primordium that migrates from head to tail deposits neuromasts in the trunk. Hippo and Wnt pathway genes, which are highly expressed in the leading edge of the migrating primordium containing mostly the undifferentiated mesenchymal-like progenitors (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008; Kozlovskaja-Gumbrienė et al., 2017), get silenced when the leading progenitors differentiate into SCs and HCs (Jiang et al., 2014; Kozlovskaja-Gumbrienė et al., 2017). However, the severe-injury-treated neuromast displayed the expression patterns of leading progenitors in early developing primordium, which suggests that lin28a reprograms the differentiated cells into the stem/progenitor cells at early developmental stage.

Although resident stem/progenitor cells are required for homeostasis and regeneration in most tissues, emerging evidence implies that differentiated cells are able to reprogram to stem/progenitor cells upon tissue damage to initiate regeneration (Lin et al., 2018; Tetteh et al., 2015). For example, atoh1+ secretory cells in intestine are capable to dedifferentiate into lgr5+ stem cells in irradiation-induced severe injury (Tetteh et al., 2016; Tomic et al., 2018). In colon, atoh1+ secretory progenitors reprogram to lgr5+ stem cells and form the entire crypts post injury while contributed minimally to other lineages in homeostasis (Castillo-Azofeifa et al., 2019). Since it’s well-known that lin28a, together with Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog, can reprogram somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) in mouse and human (Yu et al., 2007; Moss and Tang, 2003; Zhang et al., 2016), it may be involved in tissue regeneration through dedifferentiation. Our results showed that atoh1a+ HC precursors were converted into sox2 expressing cells through Yap-lin28a pathway (Figure 5), suggesting that lin28a may reprogram HC precursors into sox2+ progenitors. Further lineage-tracing analyses using cre/loxP system is necessary to verify whether HC precursors are dedifferentiated into sox2+ progenitors post severe injury.

Materials and methods

Key resources table.

| Reagent type (species) or resource |

Designation | Source or reference |

Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic reagent (Danio rerio) | Et(krt4:EGFP)sqet20ET | Parinov et al., 2004 | sqET20; RRID:ZFIN_ZDB-ALT-070628-20 | |

| Genetic reagent (Danio rerio) | Et(krt4:EGFP)sqet4ET | Parinov et al., 2004 | sgET4; RRID:ZFIN_ZDB-GENO-110323-1 | |

| Genetic reagent (Danio rerio) |

Tg(atoh1a:

TdTomato)nns8 |

Wada et al., 2010 | nns8; RRID:ZFIN_ZDB-GENO-120530-1 | |

| Genetic reagent (Danio rerio) | sox2-2a-sfGFPstl84 | Shin et al., 2014 | stl84; RRID:ZFIN_ZDB-GENO-150721-11 | |

| Genetic reagent (Danio rerio) | Tg(brn3c:GAP43-GFP) s356t | Xiao et al., 2005 | S356t; RRID:ZFIN_ZDB-GENO-200218-3 | |

| Genetic reagent (Danio rerio) | Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP)w32 | Stoick-Cooper et al. (2007) | W32; RRID:ZFIN_ZDB-ALT-070403-1 | |

| Genetic reagent (Danio rerio) | Tg(hsp70l:myc-notch1a;cryaa:Cerulean)fb12 | Zhao et al. (2014) | fb12; RRID:ZFIN_ZDB-ALT-140522-5 | |

| Genetic reagent (Danio rerio) | Tg(hsp70:atoh1a)x20 | Millimaki et al. (2010) | X20; RRID:ZFIN_ZDB-GENO-110315-10 |

|

| Genetic reagent (Danio rerio) | yapmw48 | Miesfeld et al., 2015 | Ms48; RRID:ZFIN_ZDB-ALT-160122-5 | |

| Genetic reagent (Danio rerio) | Tg(hsp70:lin28a-P2Amcherry;cmlc:GFP)psi30 | this paper | Details in Fish strain information | |

| Genetic reagent (Danio rerio) | Tg(hsp70:let7-P2AGFP;cryaa:Venus) | this paper | Details in Fish strain information | |

| Genetic reagent (Danio rerio) | lin28apsi37 | this paper | Details in Fish strain information | |

| Antibody | anti-sox2 (Rabbit, polyclonal) | Abcam | Cat# Ab97959; RRID:AB_2341193 | IF(1:200) |

| Antibody | anti-yap (Rabbit, polyclonal) | CST | Cat# 4912, RRID:AB_2218911 | IF(1:200) |

| Antibody | anti-taz (Rabbit, polyclonal) | Abcam | Cat# Ab84927; RRID:AB_1925489 | IF (1:200), WB (1:500) |

| Antibody | anti-GFP (Mouse, monoclonal) | Invitrogen | Cat# A11120; RRID:AB_221568 | IF(1:500) |

| Antibody | Anti-yap (Mouse, monoclonal) | Santa Cruz | Cat# sc-271134; RRID:AB_10612397 | WB (1:1000) |

| Antibody | Anti-lin28a (Rabbit, polyclonal) | CST | Cat# 3978; RRID:AB_2297060 | WB (1:500) |

| Antibody | Anti-lats (Rabbit, monoclonal) | CST | Cat# 3477; RRID:AB_2133513 | WB (1:500) |

| Antibody | Anti-p-mob1 (Rabbit, monoclonal) |

CST | Cat# 8699; RRID:AB_11139998 | WB (1:500) |

| Antibody | Anti-β-actin (Mouse, monoclonal) | Sigma | Cat# A1978; RRID:AB_476692 | WB (1:2000) |

| Antibody | Anti-digoxingenin POD (sheep, polyclonal) | Roche | 11207733910; RRID:AB_514500 | 1:2000 |

| Antibody | Anti-fluorescein POD(sheep, polyclonal) | Roche | 11426346910; RRID:AB_840257 | 1:2000 |

| Chemical compound, drug | EdU | Carbosynth | NE08701 | 3.3 mM |

| Chemical compound, drug | LY411575 | Santa Cruz | sc-364529 | 2 μM |

| Chemical compound, drug | Neomycin sulfate | Sigma | N6386 | 300 μM |

| Chemical compound, drug | Alexa Fluor-594 Azide | Thermo Fisher Scientific | N6386 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | Verteporfin | Selleckchem | S1786 | 5 μM |

| Chemical compound, drug | Copper sulfate | Sigma | 451657 | 50 μM |

| Chemical compound, drug | cisplatin | Sigma | 33342 | 500 μM |

| Commercial assay or kit | TSA-Cyanine 3 Reagent | PerkinElmer | SAT704A001EA | |

| Commercial assay or kit | TSA-FITC Reagent | PerkinElmer | SAT704A001EA | |

| Commercial assay or kit | dynabeads | Invitrogen | 10015D |

Fish strains

Tg(sqET20;sgET4) (Parinov et al., 2004), Tg(atoh1a:TdTomato)nns8(Wada et al., 2010), sox2-2a-sfGFPstl84 (Shin et al., 2014), Tg(brn3c:GAP43-GFP)s356t or brn3c:GFP(Xiao et al., 2005), Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP)w32 or hs:dkk1 (Stoick-Cooper et al., 2007), Tg(hsp70l:myc-notch1a;cryaa:Cerulean)fb12 or hs:notch1a (Zhao et al., 2014), Tg(hsp70:atoh1a)x20 or hs:atoh1a (Millimaki et al., 2010), yapmw48 (Miesfeld et al., 2015) were used. To generate Tg(hsp70:lin28a-P2Amcherry;cmlc:GFP)psi30 or hs:lin28a line, the lin28a coding sequence was cloned into the Gateway destination vector containing the hsp70 promoter. To generate Tg(hsp70:let7-P2AGFP;cryaa:Venus) or hs:let7 line, the expression cassette of pri-let-7a and pri-let-7f in UI4-GFP-SIBR backbone (Ramachandran et al., 2010) was subcloned into the Gateway destination vector containing the hsp70 promoter. To create lin28apsi37 mutant or lin28a-/-, 50 pg Cas9 protein (PNA Bio) and 50 pg sgRNA (GAGGGTTTTCGCAGTCTGA) were injected per embryo. F0 founders were screened by genotyping F1 embryos with PCR (F: TGTTTGACATCTCTGCAGAGC, R:CACCGATCTCCTTTTGACCG) followed by Hpy188I digestion. The yapmw69 mutant was genotyped with PCR primers (F:AGTCATGGATCCGAACCAGCACAA, R:TGCAATCGGCCTTTATTTTCCTGC) followed by HinfI digestion.

Pharmacological inhibitors and heat-shock experiments

The γ-secretase inhibitor LY411575 (Santa Cruz sc-364529) was added to larvae at 2 μM from 3dpf to 5dpf. The inhibitor of yap-tead1 complext verteporfin (Selleckchem S1786)was added to larvae at 5 μM. Larvae at 5dpf were heat-shocked at 39°C for 30 min and sometimes heat-shock is repeated to maintain the target gene expression. hs:lin28a or hs:let7 larvae were sorted by GFP in heart or Venus in eye at 3dpf. hs:notch1a were sorted by Cerulean fluorescence in eye at 3dpf. And hs:dkk1 larvae were sorted by GFP after heat-shock. hs:atoh1a were genotyped by primers GCAGCCTGACAGGACTTTTC and GCTGCTCTTCCTGAAGTTGG.

Regeneration experiments, EdU incorporation

To ablate HCs, larvae at 5dpf were treated with 300 μM neomycin (Fisher Scientific) for 30 min, 500 μM cisplatin (Sigma Aldrich, 33342) for 2 hr, or 50 μM CuSO4 (Sigma Aldrich, 451657) for 2 hr. To ablate both SCs and HCs to induce severe injury, we added 2 μM LY411575 from 3dpf to 5dpf and then treated with neomycin. Afterwards, larvae were first rinsed three times in fresh 0.5x E2 medium, and incubated in fresh medium. EdU (Carbosynth, NE08701, diluted in 3.3 mM with E2 medium containing 1% DMSO) was used to label larvae for the indicated time at 28.5°C before collecting for staining. Incorporated EdU was stained with Azide-594 (Invitrogen, N6386). The numbers and relative positions of EdU-positive cells in neuromast were analyzed as described in Romero-Carvajal et al., 2015.

In situ hybridization

The following probes were used: atoh1a, her4.1, fgf3, wnt10a (Jiang et al., 2014), yap1, mst2(Kozlovskaja-Gumbrienė et al., 2017), mycn, ccnd1(Yamaguchi et al., 2005), s100t(Venero Galanternik et al., 2015), dkk2 (Wada et al., 2013). lin28a was cloned with primers (F: CATTACCATCCCGTGAAGAGGGTCCTGGTTCTG and R: CCAATTCTACCCGTGTGCAACAACACACTCAGC) and subcloned into pPR-T4P for probe synthesis. In situ hybridization was performed as described in Jiang et al. (2014). Digoxigenin-labeled atoh1a probe and fluorescein-labeled lin28a probe were used for double fluorescent in situ. We first incubated the larvae with atoh1a probe followed by anti-digoxingenin POD antibody and colorized with TSA-FITC substrate. Then samples were incubated with lin28a probe followed by anti-fluorescein POD antibody and colorized with TSA-Cyanine 3 substrate.

Immunostaining and live imaging

Antibodies against sox2 (Abcam, Ab97959), yap (Cell Signaling Technology, 4912), taz (Abcam, Ab84927), GFP (Invitrogen, A11120) were used for immunostaining as described in Kozlovskaja-Gumbrienė et al. (2017). Images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM780 or LSM800 confocal microscope using an Apochromat 40 × 1.1 NA objective. For time-lapse imaging larvae at 5dpf were anesthetized with tricaine and mounted in 1.2% low melting point agarose on glass bottom dishes.

Western blot and CHIP experiments

About 30 larvae at 5dpf were lysed with 150 μl SDS buffer (63 mM Tris-HCl PH6.8, 10% glycerol, 100 mM DTT, 3.5% SDS) to extract protein for western blot. The primary antibodies used are yap (Santa Cruz, sc-271134), lin28a (CST, 3978), taz (Abcam, Ab84927), lats1 (CST, 3477), p-mob1 (CST 8699), β-actin (Sigma, A1978). CHIP experiments were performed as described in zfin (https://wiki.zfin.org/display/prot/Chromatin+Immunoprecipitation+%28ChIP%29+Protocol+using+Dynabeads). Antibody against yap (Santa Cruz, sc-271134) and dynabeads (Invitrogen, 10015D) were used to immunoprecipitate yap-bound nuclear DNA. PCR was performed with primers F:GATAATGATTGCATCACGTGAC and R:CATGCAGGATTCTTGGATGC to detect the region surrounding transcription start site of lin28a.

Laser ablation

Larvae at 5dpf were mounted in agarose and numbered individually for laser ablation. Laser ablation was performed with a Chameleon Ultra II laser tuned to 800 nm. Regions of 2 μm diameter were bleached for 30 cycles in ZEN. Illumination power was adjusted as necessary to ensure that destruction of the targeted regions occurred but limited to only targeted areas. This could range anywhere from 40 mW to 400 mW and varied from sample to sample. Imaging was performed with an LD C-Apochromat 40 × 1.1 NA objective, with 0.5 μm pixel spacing and 1.6μs dwell time with 512 × 512 pixels. The numbered larvae were then recovered and fixed in 4% PFA for testing in situ individually.

Yap expression analysis

Individual nuclei, labeled with DAPI, were automatically identified by finding local maxima on a Lorentzian of Gaussian filtered image. The area around identified points was automatically quantified in the yap channel. A yap-positive and yap-negative cell were manually selected from the vicinity of each neuromast, and only cells having intensity above the positive were counted as yap-nuclear-positive. All processings were done in ImageJ, and customized macros and plugins can be found at https://github.com/jouyun/smc-macros/blob/master/2DSpotFinder.ijm.

Cell counting and data analysis

GFP in ET20 was used to label MC while GFP in ET4 was used to label HC. The SC number was counted by DAPI stained cells with no ET4;ET20 expression. About 3–4 neuromasts from 4 to 6 fish were used for cell counting. The polarization analysis was performed as in Romero-Carvajal et al., 2015, and the enrichment in dorsal-ventral poles was calculated by Binomial analysis. All data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t-test for experiments with two groups. One-way ANOVA was used for more than two groups. * indicates p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Acknowledgements

We thank T Piotrowski and M Lush in Stowers Institute for Medical Research, B Link in Medical College of Wisconsin and L Solnica-Krezel in Washington University for providing fish lines; Sean Mckinney in Stowers Institute for support of imaging and data analysis. This work was supported by grants from National Key R and D Program of China (2018YFA0108304), National Science Foundation of China (81800164, 31871467), Guangdong Science and Technology (2018A030313497), Shenzhen Foundation of Science and Technology (JCYJ20170818103626421), the Key Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2019B020234002),Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (19ykpy98).

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Contributor Information

Yiqing Zheng, Email: zhengyiq@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Meng Zhao, Email: zhaom38@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Linjia Jiang, Email: jianglj7@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Tanya T Whitfield, University of Sheffield, United Kingdom.

Kathryn Song Eng Cheah, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Funding Information

This paper was supported by the following grants:

Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China National Key R&D Program of China 2018YFA0108304 to Linjia Jiang.

National Science Foundation Youth Project 81800164 to Linjia Jiang.

National Science Foundation General Project 31871467 to Linjia Jiang.

Guangdong Science and Technology Department basic research project 2018A030313497 to Linjia Jiang.

Guangdong Science and Technology Department The key Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province 2019B020234002 to Meng Zhao.

Shenzhen Foundation of Science and Technology JCYJ20170818103626421 to Meng Zhao.

Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities 19ykpy98 to Linjia Jiang.

Additional information

Competing interests

No competing interests declared.

Author contributions

Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology.

Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology.

Data curation, Formal analysis.

Data curation.

Data curation, Methodology.

Data curation, Formal analysis.

Supervision, Writing - review and editing.

Supervision, Writing - review and editing.

Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing - review and editing.

Additional files

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the manuscript and supporting files.

References

- Abdolazimi Y, Stojanova Z, Segil N. Selection of cell fate in the organ of Corti involves the integration of hes/Hey signaling at the Atoh1 promoter. Development. 2016;143:841–850. doi: 10.1242/dev.129320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwala S, Duquesne S, Liu K, Boehm A, Grimm L, Link S, König S, Eimer S, Ronneberger O, Lecaudey V. Amotl2a interacts with the hippo effector Yap1 and the wnt/β-catenin effector Lef1 to control tissue size in zebrafish. eLife. 2015;4:e08201. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman A, Piotrowski T. Wnt/beta-catenin and fgf signaling control collective cell migration by restricting chemokine receptor expression. Developmental Cell. 2008;15:749–761. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson PJ, Dong Y, Gu S, Liu W, Najarro EH, Udagawa T, Cheng AG. Sox2 haploinsufficiency primes regeneration and wnt responsiveness in the mouse cochlea. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2018;128:1641–1656. doi: 10.1172/JCI97248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermingham NA, Hassan BA, Price SD, Vollrath MA, Ben-Arie N, Eatock RA, Bellen HJ, Lysakowski A, Zoghbi HY. Math1: an essential gene for the generation of inner ear hair cells. Science. 1999;284:1837–1841. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai T, Jen HI, Kang H, Klisch TJ, Zoghbi HY, Groves AK. Characterization of the transcriptome of nascent hair cells and identification of direct targets of the Atoh1 transcription factor. Journal of Neuroscience. 2015;35:5870–5883. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5083-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai T, Groves AK. The role of atonal factors in mechanosensory cell specification and function. Molecular Neurobiology. 2015;52:1315–1329. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8925-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Azofeifa D, Fazio EN, Nattiv R, Good HJ, Wald T, Pest MA, de Sauvage FJ, Klein OD, Asfaha S. Atoh1+ secretory progenitors possess renewal capacity independent of Lgr5+ cells during colonic regeneration. The EMBO Journal. 2019;38:e99984. doi: 10.15252/embj.201899984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Zhang S, Chai R, Li H. Hair cell regeneration. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2019;1130:1–16. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-6123-4_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A, Powell LM, Lowell S, Jarman AP. Atoh1 in sensory hair cell development: constraints and cofactors. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2017;65:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox BC, Chai R, Lenoir A, Liu Z, Zhang L, Nguyen DH, Chalasani K, Steigelman KA, Fang J, Rubel EW, Cheng AG, Zuo J. Spontaneous hair cell regeneration in the neonatal mouse cochlea in vivo. Development. 2014;141:816–829. doi: 10.1242/dev.103036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz IA, Kappedal R, Mackenzie SM, Hailey DW, Hoffman TL, Schilling TF, Raible DW. Robust regeneration of adult zebrafish lateral line hair cells reflects continued precursor pool maintenance. Developmental Biology. 2015;402:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabdoub A, Puligilla C, Jones JM, Fritzsch B, Cheah KS, Pevny LH, Kelley MW. Sox2 signaling in prosensory domain specification and subsequent hair cell differentiation in the developing cochlea. PNAS. 2008;105:18396–18401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808175105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden EJ, Benito-Gonzalez A, Doetzlhofer A. The RNA-binding protein LIN28B regulates developmental timing in the mammalian cochlea. PNAS. 2015;112:E3864–E3873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501077112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorieff A, Liu Y, Inanlou MR, Khomchuk Y, Wrana JL. Yap-dependent reprogramming of Lgr5(+) stem cells drives intestinal regeneration and Cancer. Nature. 2015;526:715–718. doi: 10.1038/nature15382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorieff A, Wrana JL. Hippo signalling in intestinal regeneration and Cancer. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2017;48:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddon C, Jiang YJ, Smithers L, Lewis J. Delta-Notch signalling and the patterning of sensory cell differentiation in the zebrafish ear: evidence from the mind bomb mutant. Development. 1998;125:4637–4644. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.23.4637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JA, Cheng AG, Cunningham LL, MacDonald G, Raible DW, Rubel EW. Neomycin-induced hair cell death and rapid regeneration in the lateral line of zebrafish (Danio rerio) JARO - Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology. 2003;4:219–234. doi: 10.1007/s10162-002-3022-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández PP, Olivari FA, Sarrazin AF, Sandoval PC, Allende ML. Regeneration in zebrafish lateral line neuromasts: expression of the neural progenitor cell marker sox2 and proliferation-dependent and-independent mechanisms of hair cell renewal. Developmental Neurobiology. 2007;67:637–654. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumikawa M, Minoda R, Kawamoto K, Abrashkin KA, Swiderski DL, Dolan DF, Brough DE, Raphael Y. Auditory hair cell replacement and hearing improvement by Atoh1 gene therapy in deaf mammals. Nature Medicine. 2005;11:271–276. doi: 10.1038/nm1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacques BE, Montgomery WH, Uribe PM, Yatteau A, Asuncion JD, Resendiz G, Matsui JI, Dabdoub A. The role of wnt/β-catenin signaling in proliferation and regeneration of the developing basilar papilla and lateral line. Developmental Neurobiology. 2014;74:438–456. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Romero-Carvajal A, Haug JS, Seidel CW, Piotrowski T. Gene-expression analysis of hair cell regeneration in the zebrafish lateral line. PNAS. 2014;111:E1383–E1392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402898111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian LM, Vandenbosch R, Pakenham CA, Andrusiak MG, Nguyen AP, McClellan KA, Svoboda DS, Lagace DC, Park DS, Leone G, Blais A, Slack RS. Opposing regulation of Sox2 by cell-cycle effectors E2f3a and E2f3b in neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:440–452. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan AE, Pelling AL, Leung KK, Tang AS, Bell DM, Tease C, Lovell-Badge R, Steel KP, Cheah KS. Sox2 is required for sensory organ development in the mammalian inner ear. Nature. 2005;434:1031–1035. doi: 10.1038/nature03487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlovskaja-Gumbrienė A, Yi R, Alexander R, Aman A, Jiskra R, Nagelberg D, Knaut H, McClain M, Piotrowski T. Proliferation-independent regulation of organ size by fgf/Notch signaling. eLife. 2017;6:e21049. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanford PJ, Lan Y, Jiang R, Lindsell C, Weinmaster G, Gridley T, Kelley MW. Notch signalling pathway mediates hair cell development in mammalian cochlea. Nature Genetics. 1999;21:289–292. doi: 10.1038/6804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Srikanth P, Castle AC, Nigwekar S, Malhotra R, Galloway JL, Sykes DB, Rajagopal J. Modulating cell fate as a therapeutic strategy. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lush ME, Diaz DC, Koenecke N, Baek S, Boldt H, St Peter MK, Gaitan-Escudero T, Romero-Carvajal A, Busch-Nentwich EM, Perera AG, Hall KE, Peak A, Haug JS, Piotrowski T. scRNA-Seq reveals distinct stem cell populations that drive hair cell regeneration after loss of Fgf and notch signaling. eLife. 2019;8:e44431. doi: 10.7554/eLife.44431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma EY, Rubel EW, Raible DW. Notch signaling regulates the extent of hair cell regeneration in the zebrafish lateral line. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:2261–2273. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4372-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miesfeld JB, Gestri G, Clark BS, Flinn MA, Poole RJ, Bader JR, Besharse JC, Wilson SW, Link BA. Yap and taz regulate retinal pigment epithelial cell fate. Development. 2015;142:3021–3032. doi: 10.1242/dev.119008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millimaki BB, Sweet EM, Riley BB. Sox2 is required for maintenance and regeneration, but not initial development, of hair cells in the zebrafish inner ear. Developmental Biology. 2010;338:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutari K, Fujioka M, Hosoya M, Bramhall N, Okano HJ, Okano H, Edge ASB. Notch Inhibition Induces Cochlear Hair Cell Regeneration and Recovery of Hearing after Acoustic Trauma. Neuron. 2013;77:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss EG, Tang L. Conservation of the heterochronic regulator Lin-28, its developmental expression and microRNA complementary sites. Developmental Biology. 2003;258:432–442. doi: 10.1016/S0012-1606(03)00126-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moya IM, Halder G. The Hippo pathway in cellular reprogramming and regeneration of different organs. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2016;43:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolson T. The genetics of hearing and balance in zebrafish. Annual Review of Genetics. 2005;39:9–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.105049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parinov S, Kondrichin I, Korzh V, Emelyanov A. Tol2 transposon-mediated enhancer trap to identify developmentally regulated zebrafish genes in vivo. Developmental Dynamics. 2004;231:449–459. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto-Teixeira F, Viader-Llargués O, Torres-Mejía E, Turan M, González-Gualda E, Pola-Morell L, López-Schier H. Inexhaustible hair-cell regeneration in young and aged zebrafish. Biology Open. 2015;4:903–909. doi: 10.1242/bio.012112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran R, Fausett BV, Goldman D. Ascl1a regulates müller Glia dedifferentiation and retinal regeneration through a Lin-28-dependent, let-7 microRNA signalling pathway. Nature Cell Biology. 2010;12:1101–1107. doi: 10.1038/ncb2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Carvajal A, Navajas Acedo J, Jiang L, Kozlovskaja-Gumbrienė A, Alexander R, Li H, Piotrowski T. Regeneration of sensory hair cells requires localized interactions between the notch and wnt pathways. Developmental Cell. 2015;34:267–282. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J, Chen J, Solnica-Krezel L. Efficient homologous recombination-mediated genome engineering in zebrafish using TALE nucleases. Development. 2014;141:3807–3818. doi: 10.1242/dev.108019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoick-Cooper CL, Weidinger G, Riehle KJ, Hubbert C, Major MB, Fausto N, Moon RT. Distinct Wnt signaling pathways have opposing roles in appendage regeneration. Development. 2007;134:479–489. doi: 10.1242/dev.001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetteh PW, Farin HF, Clevers H. Plasticity within stem cell hierarchies in mammalian epithelia. Trends in Cell Biology. 2015;25:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetteh PW, Basak O, Farin HF, Wiebrands K, Kretzschmar K, Begthel H, van den Born M, Korving J, de Sauvage F, van Es JH, van Oudenaarden A, Clevers H. Replacement of Lost Lgr5-Positive Stem Cells through Plasticity of Their Enterocyte-Lineage Daughters. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomic G, Morrissey E, Kozar S, Ben-Moshe S, Hoyle A, Azzarelli R, Kemp R, Chilamakuri CSR, Itzkovitz S, Philpott A, Winton DJ. Phospho-regulation of ATOH1 is required for plasticity of secretory progenitors and tissue regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venero Galanternik M, Kramer KL, Piotrowski T. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans regulate fgf signaling and cell polarity during collective cell migration. Cell Reports. 2015;10:414–428. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viader-Llargués O, Lupperger V, Pola-Morell L, Marr C, López-Schier H. Live cell-lineage tracing and machine learning reveal patterns of organ regeneration. eLife. 2018;7:e30823. doi: 10.7554/eLife.30823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada H, Ghysen A, Satou C, Higashijima S, Kawakami K, Hamaguchi S, Sakaizumi M. Dermal morphogenesis controls lateral line patterning during postembryonic development of teleost fish. Developmental Biology. 2010;340:583–594. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada H, Ghysen A, Asakawa K, Abe G, Ishitani T, Kawakami K. Wnt/Dkk Negative Feedback Regulates Sensory Organ Size in Zebrafish. Current Biology. 2013;23:1559–1565. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield TT. Zebrafish as a model for hearing and deafness. Journal of Neurobiology. 2002;53:157–171. doi: 10.1002/neu.10123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wibowo I, Pinto-Teixeira F, Satou C, Higashijima S, López-Schier H. Compartmentalized notch signaling sustains epithelial mirror symmetry. Development. 2011;138:1143–1152. doi: 10.1242/dev.060566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JA, Holder N. Cell turnover in neuromasts of zebrafish larvae. Hearing Research. 2000;143:171–181. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(00)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao T, Roeser T, Staub W, Baier H. A GFP-based genetic screen reveals mutations that disrupt the architecture of the zebrafish retinotectal projection. Development. 2005;132:2955–2967. doi: 10.1242/dev.01861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi M, Tonou-Fujimori N, Komori A, Maeda R, Nojima Y, Li H, Okamoto H, Masai I. Histone deacetylase 1 regulates retinal neurogenesis in zebrafish by suppressing Wnt and Notch signaling pathways. Development. 2005;132:3027–3043. doi: 10.1242/dev.01881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SM, Chen W, Guo WW, Jia S, Sun JH, Liu HZ, Young WY, He DZ. Regeneration of stereocilia of hair cells by forced Atoh1 expression in the adult mammalian cochlea. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e46355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao K, Qiu S, Tian L, Snider WD, Flannery JG, Schaffer DV, Chen B. Wnt regulates proliferation and neurogenic potential of müller glial cells via a Lin28/let-7 miRNA-Dependent pathway in adult mammalian retinas. Cell Reports. 2016;17:165–178. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Ratanasirintrawoot S, Chandrasekaran S, Wu Z, Ficarro SB, Yu C, Ross CA, Cacchiarelli D, Xia Q, Seligson M, Shinoda G, Xie W, Cahan P, Wang L, Ng SC, Tintara S, Trapnell C, Onder T, Loh YH, Mikkelsen T, Sliz P, Teitell MA, Asara JM, Marto JA, Li H, Collins JJ, Daley GQ. LIN28 regulates stem cell metabolism and conversion to primed pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:66–80. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Xu J, Maire P, Xu PX. Six1 is essential for differentiation and patterning of the mammalian auditory sensory epithelium. PLOS Genetics. 2017;13:e1006967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Borikova AL, Ben-Yair R, Guner-Ataman B, MacRae CA, Lee RT, Burns CG, Burns CE. Notch signaling regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation during zebrafish heart regeneration. PNAS. 2014;111:1403–1408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311705111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng F, Zuo J. Cochlear hair cell regeneration after noise-induced hearing loss: does regeneration follow development? Hearing Research. 2017;349:182–196. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong C, Fu Y, Pan W, Yu J, Wang J. Atoh1 and other related key regulators in the development of auditory sensory epithelium in the mammalian inner ear: function and interplay. Developmental Biology. 2019;446:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]