Abstract

Background:

Cefazolin is the first-line prophylactic antibiotic used to prevent surgical site infections (SSIs) in cardiac surgery. Patients with a history of penicillin allergy often receive less effective second-line antibiotics, which is associated with an increased SSI risk.

Objective:

We aimed to describe the impact of pre-operative penicillin allergy evaluation on peri-operative cefazolin use in cardiac surgery patients.

Methods:

We performed a retrospective cohort study of patients with a documented penicillin allergy who underwent cardiac surgery at the Massachusetts General Hospital from September 2015 through December 2018. We describe penicillin allergy evaluation assessment and outcomes. We evaluated the relation between preoperative penicillin allergy evaluation and first-line peri-operative antibiotic use using a multivariable logistic regression model.

Results:

Of 3,802 cardiac surgical patients, 510 (13%) had a documented penicillin allergy; 165 (33%) were referred to Allergy/Immunology. Of 160 (31%) patients who underwent penicillin allergy evaluation (i.e., penicillin skin testing and, if negative, an amoxicillin challenge), 154 (97%) were found not to have a penicillin allergy. Patients who underwent pre-operative penicillin allergy evaluation were more likely to receive the first-line peri-operative antibiotic (92% vs 38%, p < 0.001). After adjusting for potential confounders, patients who underwent pre-operative penicillin allergy evaluation had higher odds of first-line peri-operative antibiotic use (adjusted odds ratio 26.6 [95% CI: 12.8, 55.2]).

Conclusion:

Integrating penicillin allergy evaluation into routine pre-operative care ensured that almost all cardiac surgery patients evaluated received first-line antibiotic prophylaxis, a critical component of SSI risk reduction. Further efforts are needed to increase access to pre-operative allergy evaluation.

Keywords: allergy, beta-lactam, hypersensitivity, cardiothoracic, surgical site infection, prophylaxis

INTRODUCTION

Every year in the United States (U.S.), there are approximately 110,800 cases of surgical site infections (SSIs).1 These infections not only carry a mortality of 3%, but they also prolong hospitalization by an average of 11 days per patient and cost the U.S. health care system more than $3.3 billion dollars annually.1-6 As approximately half of SSIs are considered preventable, evidence-based strategies to decrease SSIs should be investigated and implemented.7

While the use of peri-operative prophylactic antibiotics decreases SSI risk, the choice of antibiotic and the time it is administered are also important factors in determining prophylactic antibiotic efficacy.8 Cefazolin, a first-generation cephalosporin, is the preferred first-line peri-operative antibiotic in most procedures due to its ability to rapidly reach bactericidal concentrations against common skin flora including methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus species.9-12 This is especially pertinent in cardiac surgery patients because staphylococci are the primary pathogens in both sternal and vein donor site infections.13 However, in the approximately 10% of surgical patients who report a penicillin allergy, cefazolin is routinely avoided due to fear of cross-reactivity, and instead second-line antibiotics including vancomycin, fluoroquinolones, and clindamycin are used in the majority of cases.14 Not only are these antibiotics associated with higher odds of SSI, they also have been associated with multidrug resistant organisms, increased rates of Clostridioides difficile infection, and other adverse events.9,15 This suboptimal choice in peri-operative antibiotic occurs despite cefazolin having very low likelihood of cross-reactivity with penicillins (1-2%) and clinically significant penicillin hypersensitivity being rare in patients reporting penicillin allergy histories (<5%).’16 Previous studies demonstrated that patients with a documented penicillin allergy have a 50%-65% increased odds of SSI, entirely attributable to the receipt of second-line peri-operative antibiotics.9,17 The objective of our study was to describe the impact of pre-operative penicillin allergy evaluation on first-line peri-operative antibiotic use in cardiac surgery patients.

METHODS

Data Source

We performed an observational retrospective cohort study of patients with reported penicillin allergy who underwent cardiac surgery at a large Boston-based academic medical center from September 2015 to December 2018. During this time, as part of hospital quality improvement initiatives, the Cardiac Surgery division began to routinely refer patients scheduled for surgery with a penicillin allergy history for testing on a case-by-case basis. We identified patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), aortic valve replacement (AVR), mitral valve replacement (MVR), mitral valve repair (MV repair), CABG + AVR, CABG + MVR, and other cardiac surgeries using the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database, the national clinical registry for cardiac surgery.18 We subsequently identified patients with a documented penicillin allergy history prior to their surgery date using allergy module data from the Enterprise Data Warehouse, the comprehensive electronic health record (EHR) database. Documented penicillin allergy, and the associated penicillin reaction(s), were manually verified by a medical doctor (J.H.P.).

Exposure

The exposure of interest was a pre-operative penicillin allergy evaluation, defined as either outpatient or inpatient penicillin allergy assessment. All penicillin allergy assessmentswere performed by an Allergy/Immunology provider, largely in the outpatient setting. While this academic medical center uses a standardized risk stratification tool to evaluate patients with penicillin allergy histories,19 all cardiac surgery patients were considered high risk hosts given that they have compromised cardiac anatomy requiring pending surgical intervention, and therefore their evaluation began with history-appropriate penicillin skin testing.

Penicillin skin testing was performed with both epicutaneous (prick-puncture) and intradermal steps with Penicilloyl-polylysine (Pre-Pen®), Penicillin G, histamine (positive control), and saline (negative control). Patients with negative penicillin skin testing received amoxicillin 500 mg, were monitored for an hour. If no penicillin allergy was identified, the penicillin allergy label in the EHR was deleted, and the allergist’s note indicated that: (1) there was no penicillin allergy and (2) cefazolin could be used pre-operatively. The allergist’s note was communicated electronically to the referring provider upon being signed.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was first-line peri-operative antibiotic prophylaxis; for all cardiac surgeries considered, this was defined as cefazolin administered from one hour prior to surgery until the end of surgery.10 Of note, even for patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) colonization, cefazolin is recommended (along with vancomycin).10

We considered hospital length of stay, defined as the total number of hospital days for the patient encounter that included the cardiac surgery, as a secondary outcome. This was calculated as an integer value by subtracting the admission date from the discharge date. SSI was also considered as a secondary outcome, and was defined according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Healthcare Safety Network definitions and included all types: superficial, deep, and organ space.1

Covariates and confounders

Age, sex and race were identified from the EHR demographic section. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from height and weight assessments at the time of surgery. American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class was identified from the pre-operative anesthesiology visit and documented according to established guidelines.20 Resistant organism colonization was identified using EHR “flags” for patients with MRSA and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) at the time of surgery, which were maintained by the facility’s infection control staff. Documented cephalosporin allergy was identified from the allergy module considering the allergy history prior to surgery date. Surgery type and status was identified from the STS database according to standard definitions.18

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations (SD) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), as appropriate. Categorical variables were presented as n (%). We compared patient and procedure characteristics in patients with a penicillin allergy history who did and did not undergo pre-operative allergy evaluation using the t test for continuous variables and chi-square tests for binary or categorical variables. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to evaluate the relation between penicillin allergy evaluation and first-line peri-operative antibiotic use. Wilcoxon rank sum was used to compare median length of stay between patients with a penicillin allergy who did and did not undergo pre-operative allergy evaluation. We report Odds Ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for first line peri-operative antibiotic use. All p-values were 2-sided with p<0.05 considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Cohort Description

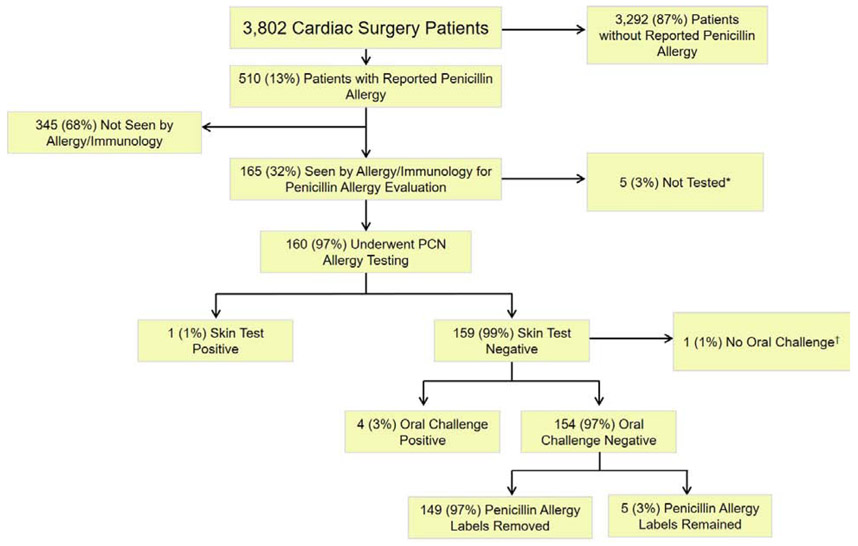

3,802 patients underwent cardiac surgery from September 2015 to December 2018 (Figure 1). Of those, 510 (13%) had a documented penicillin allergy, of whom 165 patients (33%) were evaluated by Allergy/Immunology prior to their surgery, and 160 (97% of those evaluated, and 31% of eligible) underwent penicillin allergy evaluation with skin testing. There were 159 skin test negative patients (99%), 158 of which went on to receive an oral amoxicillin challenge (direct oral challenge in one patient was deferred per the primary inpatient team and not completed). 154 skin test negative patients (97%) tolerated the oral amoxicillin challenge with 149 (97%) having their penicillin allergy label appropriately removed prior to surgery.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Cardiac Surgery Patients with a Documented Penicillin Allergy

* After assessing the drug allergy history, Allergy/Immunology recommended that cefazolin could be administered directly in four patients and in one patient, testing was not recommended due to a recent penicillin reaction.

† Inpatient with negative penicillin skin testing had drug challenge deferred by primary team

Patients who did and did not undergo penicillin allergy evaluation were of similar age, sex, race, BMI and ASA class (Table 1). Comparing patients who underwent various types of cardiac surgeries, patients who had a CABG were less likely to have pre-operative allergy evaluation (17% vs 40%, p<0.001) whereas patients who underwent valvular surgeries (AVR, MVR, MV repair) were more likely to have pre-operative allergy assessment (38% vs 14%, p<0.001). Patients with elective surgeries were more likely to undergo pre-operative allergy assessment (84% vs 42%, p<0.001), whereas those with urgent surgeries (15% vs 50%, p<0.001) and emergent surgeries (1% vs 8%, p<0.001) were less likely to have a pre-operative allergy evaluation. There was no difference between VRE and MRSA colonization frequency by exposure groups. Cardiac surgery patients who did and did not undergo pre-operative allergy assessment had similar penicillin reactions recorded; however, patients with gastrointestinal symptoms, (3% vs 16%, p <0.001) and other reactions (5% vs 10%, p = 0.044) were less likely to undergo pre-operative allergy evaluation, whereas patients with urticaria (26.7% vs 17%, p= 015) and itching/flushing (7% vs 3%, p = 0.045) were more likely to have had pre-operative allergy evaluation. There were similar frequencies of documented cephalosporin allergy histories between patients who did and did not undergo pre-operative allergy assessment.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Cardiac Surgery Patients with a Penicillin Allergy

| Penicillin Allergy Evaluation (n= 165, 32%) |

No Penicillin Allergy Evaluation (n=345, 68%) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||

| Age ( + SD) | 63 ± 13 | 65 ± 14 | 0.13 |

| Sex | 0.23 | ||

| Male | 82 (50) | 191 (55) | |

| Female | 83 (50) | 154 (45) | |

| Race | 0.79 | ||

| White | 149 (90) | 311 (90) | |

| Black | 4 (2) | 7 (2) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (1) | 6 (2) | |

| Asian | 4 (2) | 4 (1) | |

| Other | 6 (4) | 17 (5) | |

| BMI ( + SD) | 29.4 ± 7 | 29.2 ± 6 | 0.38 |

| SURGICAL DETAILS | |||

| ASA class | 0.062 | ||

| II | 7 (4) | 7 (2) | |

| III | 105 (64) | 196 (57) | |

| IV | 53 (32) | 136 (39) | |

| V | 0 (0) | 6 (2) | |

| Type of Surgery | < 0.001 | ||

| CABG | 28 (17) | 139 (40) | |

| AVR, MVR, MV Repair | 63 (38) | 47 (14) | |

| CABG + MVR/AVR | 9 (5) | 24 (7) | |

| Other | 65 (39) | 135 (39) | |

| Status of Surgery | < 0.001 | ||

| Elective | 139 (84) | 144 (42) | |

| Urgent | 25 (15) | 173 (50) | |

| Emergent | 1 (1) | 28 (8) | |

| MRSA colonization | 6 (4) | 10 (3) | 0.65 |

| VRE colonization | 5 (3) | 17 (5) | 0.48 |

| ALLERGY HISTORY | |||

| Penicillin allergy | |||

| Rash | 63 (38) | 104 (30) | 0.07 |

| Urticaria | 44 (27) | 60 (17) | 0.015 |

| Gastrointestinal Symptoms | 5 (3) | 54 (16) | < 0.001 |

| Angioedema/swelling | 18 (11) | 27 (8) | 0.25 |

| Anaphylaxis/hypotension | 7 (4) | 18 (5) | 0.63 |

| Itching/flushing | 11 (7) | 10 (3) | 0.045 |

| Shortness of breath | 4 (2) | 6 (2) | 0.60 |

| Acute interstitial nephritis | 0 (0) | 2 (<1) | 0.33 |

| Other | 8 (5) | 35 (10) | 0.044 |

| Unknown | 27 (16) | 72 (21) | 0.23 |

| Cephalosporin allergy | 15 (9) | 30 (9) | 0.88 |

Abbreviations: , sample mean; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; AVR, aortic valve replacement; MVR, mitral valve replacement; MV, mitral valve; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VRE, vancomycin resistant Enterococci

Outcomes

Patients who underwent pre-operative penicillin allergy evaluation were more likely to receive the first-line peri-operative antibiotic (92% vs 38%, p < 0.001, Table 2). Adjusting for age, sex, race, BMI, ASA class, surgery type, surgery status, MRSA, VRE, penicillin reaction, and cephalosporin allergy history, patients who underwent penicillin allergy evaluation had higher odds of receiving the first-line peri-operative antibiotics than those who did not undergo penicillin allergy evaluation (adjusted odds ratio 26.6 [95% CI: 12.8, 55.2], Table 3).

Table 2.

Univariable Assessment of Pre-operative Penicillin Allergy Evaluation on Clinical Outcomes

| Total patients with penicillin allergy history (n = 510) |

Penicillin Allergy Evaluation (n = 165) |

No Penicillin Allergy Evaluation (n = 345) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-line perioperative antibiotic used, n (%) | 284 (56) | 152 (92) | 132 (38) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital length of stay (days), Med [IQR] | 9 [6, 14] | 8 [5, 11] | 10 [7, 16] | < 0.001 |

| Surgical site infection, n (%) | 13 (2.6) | 3 (1.8) | 10 (2.9) | 0.47 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range

Table 3.

Multivariable Model of Pre-Operative Penicillin Allergy Evaluation Impact on Clinical Outcomes

| Penicillin Allergy Evaluation Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

No Penicillin Allergy Evaluation |

|

|---|---|---|

| First-line peri-operative antibiotic used | 26.6 (12.8, 55.2) | 1.0 (Reference) |

Adjusted by age, sex, race, BMI, ASA class, surgery type, surgery status, MRSA, VRE, penicillin reaction, and cephalosporin allergy.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VRE, vancomycin resistant Enterococci

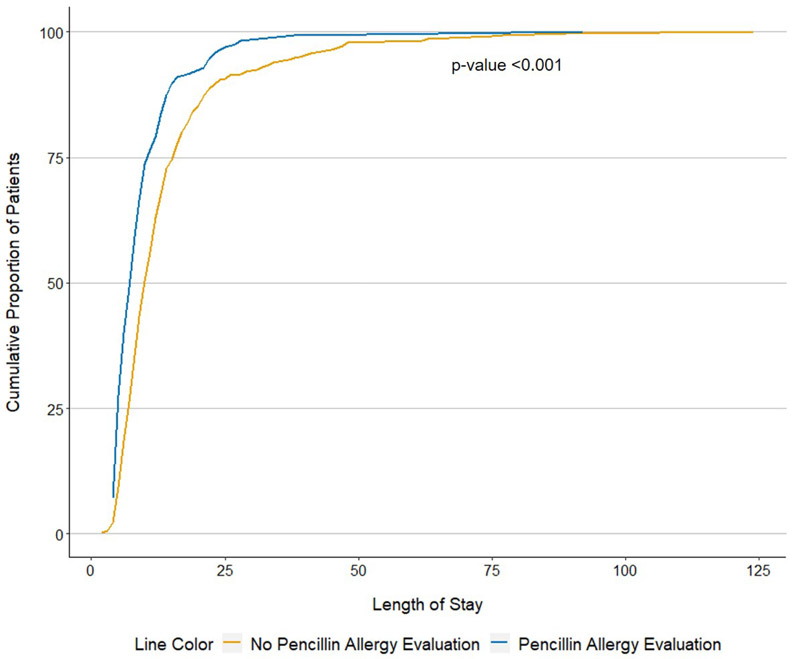

Patients with penicillin allergy evaluation had shorter median hospital lengths of stay (8 days [5 days, 11 days] vs 10 days [7 days, 16 days], p<0.001, Figure 2, Table 2). SSIs were rare in both groups (1.8% vs 2.9%, p = 0.47, Table 2).

Figure 2.

Length of Hospital Stay for Cardiac Surgery Patients with a Documented Penicillin Allergy

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective cohort study, we identified that 13% of patients who underwent cardiac surgeries had a penicillin allergy history. Patients who underwent pre-operative allergy evaluation were approximately 27 times more likely to receive first-line antibiotic prophylaxis with cefazolin. Our study demonstrates the importance and impact of incorporating pre-operative penicillin allergy evaluation for patients who require surgeries where the peri-operative antibiotic of choice is cefazolin or another beta-lactam to maximize SSI prevention strategies.

We found that 92% of penicillin allergy evaluated patients received peri-operative cefazolin, while just 38% of those not evaluated by Allergy/Immunology received cefazolin. Our prior study of more than 9,000 surgeries from 2010-2014 identified that just 12% of patients with a penicillin allergy history received perioperative cefazolin.9 In this study, after controlling for baseline patient and procedure differences between groups, there was a large and significant 27 times increased odds of cefazolin use in the patients who received Allergy/Immunology assessment. This adjusted odds is notably better than found in a recent meta-analysis of 4 studies where penicillin allergy testing reduced non-β-lactam antibiotic use compared with usual care by an odds ratio of 3.64.15

Although cefazolin is the first-line antibiotic recommended to prevent SSIs in cardiac surgery, patients with a history of penicillin allergy are less likely to receive cefazolin due to cross-reactivity concerns, given a shared beta-lactam ring.9,21

However, cefazolin has a unique side chain that results in low or potentially even negligible cross-reactivity.22 Few studies specifically address penicillin-cefazolin cross-reactivity; a meta-analysis of three observational studies estimated that the absolute risk of cross-reactivity to cefazolin in penicillin-allergic patients was 1.33% (95% CI 0.19% −8.86%).16 Although the risk estimate is low, the confidence interval is wide and the risk is not zero. Caution therefore is warranted given that cefazolin is the most commonly identified cause of peri-operative allergic reactions in the U.S.,23 and peri-operative allergic reactions not only cause patient distress and disrupt hospital operations, but also may necessitate postponing or rescheduling of the surgery.

Although pre-operative Allergy/Immunology evaluation was tremendously effective in optimizing prophylactic antibiotics in those who were evaluated, only one-third of cardiac surgery patients with a history of penicillin allergy underwent a pre-operative allergy assessment, and there was a notable diminishing frequency in penicillin allergy evaluation in urgent and emergent surgeries (15% and 1%, respectively). For pre-operative penicillin allergy assessment program to be maximally effective, increased testing access, particularly when patients are hospitalized and surgeries are not elective, is critical, especially since SSI risk is higher for urgent and emergent procedures.24 While feasible to implement penicillin skin testing for inpatients generally,25 inpatients awaiting cardiac surgery have a crowded time-limited window where required pre-operative tests, such as dental x-rays, vein mapping, and carotid ultrasounds, must be performed.26 As an alternative, one could consider performing a test dose/drug challenge rather than skin testing, however the risks and benefits would need to be weighed given the potential consequences of precipitating a true allergic reaction in an unstable cardiac surgery patient. Improved uptake might be achieved by establishing dedicated drug allergy clinics.27 Improved uptake might also be facilitated through EHR innovations; for example, McDanel et al. described an EHR alert that triggered allergy consultation when a patient with a documented beta-lactam allergy checked into the surgical clinic.28

A penicillin allergy label has implications for clinical decision making beyond patients’ immediate peri-operative antibiotic decision. Indeed, an unverified penicillin allergy label is associated with increased MRSA, Clostridioides difficile infection, and overall mortality.29,30 As such, an upcoming surgery might be considered a good opportunity to address penicillin allergy histories that have never been questioned; and the testing provided -- if negative and the patient’s penicillin allergy is removed -- might improve individual and public health outcomes beyond the peri-operative and post-operative period.31 In our study, 97% of patients with negative penicillin allergy testing had their penicillin allergy label removed. Although this is higher than reported in other studies (72-95%),19,32 allergy specialists did erroneously leave a penicillin allergy label on 6 patients who had cardiac surgery. In order to increase delabeling to 100%, the EHR allergy module needs modification and potentially a “testing” section that can clearly communicate test results and recommendations.

Although we included only cardiac surgery patients in this study, our results are likely generalizable to the broader surgical population for whom cefazolin, or another beta-lactam antibiotic, is the first-line peri-operative antibiotic.10,21 We studied only one method of penicillin allergy evaluation in this study (i.e. history-appropriate penicillin skin testing, followed by amoxicillin challenge if the skin testing was negative). We are therefore unable to speak to the impact of alternative penicillin allergy evaluation models or methods, such as an allergy history tool or a direct amoxicillin challenge. However, one prior study identified that a structured history tool alone increased peri-operative beta-lactam use in patients with a penicillin allergy from 18% to 57%.33 Additionally, given that this specific population is a high-risk group awaiting cardiac surgery, a direct amoxicillin challenge strategy is not without risk.19,34 We captured only Allergy/Immunology evaluations that occurred within our healthcare system; however, if patients received a penicillin allergy assessment outside our healthcare system and were miscategorized in our study, this would have biased our study towards the null hypothesis, thus making our findings more conservative. Finally, while our study was powered to detect the large expected difference in first-line peri-operative antibiotic use, we were underpowered to detect differences in hospital length of stay and SSI. We will reassess these important outcomes as we continue our peri-operative penicillin allergy evaluation programs.

SSIs have enormous clinical and economic consequences. While studies have shown that patients with a penicillin allergy have 50% higher odds of SSI attributable to peri-operative antibiotic choice, our study highlights that allergist-driven pre-operative penicillin allergy assessment, which consumes only a few hours of patient-time and carries only a modest cost,35 can significantly and substantially increase the use of first-line peri-operative antibiotics.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Dr. Blumenthal receives career development support from the NIH K01AI125631, the American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) Foundation, and the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Claflin Distinguished Scholar Award. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, AAAAI Foundation, nor the MGH.

Abbreviations:

- U.S.

United States

- SSI

Surgical Site Infections

- CABG

Coronary artery bypass graft

- AVR

Aortic valve replacement

- MVR

Mitral valve replacement

- MV

Mitral valve

- STS

Society of Thoracic Surgeons

- EHR

Electronic Health Record

- MRSA

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- ASA

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- VRE

Vancomycin Resistant Enterococcus

- SD

Standard Deviation

- IQR

Interquartile Range

- CI

Confidence Interval

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

Dr. Blumenthal reports a clinical decision support tool used institutionally for beta-lactam allergy at Partners HealthCare System which is licensed to Persistent Systems. All other authors declare that they have nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.CDC surgical site infection (SSI) event; Published January 2020, Available from https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/9pscssicurrent.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- 2.Russo V, Watkins J. NHSN Surgical Site Infection Surveillance in 2019. CDC: National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases; Published March 2019, Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/training/2019/ssi-508.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(13):1198–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Awad SS. Adherence to surgical care improvement project measures and post-operative surgical site infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2012;13(4):234–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merkow RP, Ju MH, Chung JW, et al. Underlying reasons associated with hospital readmission following surgery in the United States. JAMA. 2015;313(5):483–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimlichman E, Henderson D, Tamir O, et al. Health care-associated infections: a meta-analysis of costs and financial impact on the US health care system. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(22):2039–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berrios-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection, 2017. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(8):784–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soule BM. Evidence-based principles and practices for preventing surgical site infections: Joint Commission International; 2018.

- 9.Blumenthal KG, Ryan EE, Li Y, et al. The impact of a reported penicillin allergy on surgical site infection risk. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(3):329–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Olsen KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;14(1):73–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berrios-Torres SI, Yi SH, Bratzler DW, et al. Activity of commonly used antimicrobial prophylaxis regimens against pathogens causing coronary artery bypass graft and arthroplasty surgical site infections in the United States, 2006-2009. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(3):231–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bratzler DW, Houck PM, Surgical Infection Prevention Guidelines Writers Workgroup, et al. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery: An advisory statement from the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(12):1706–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkelstein R, Rabino G, Mashiah T, et al. Vancomycin versus cefazolin prophylaxis for cardiac surgery in the setting of a high prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcal infections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;123(2):326–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou L, Dhopeshwarkar N, Blumenthal KG, et al. Drug allergies documented in electronic health records of a large healthcare system. Allergy. 2016;71(9): 1305–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reilly CA, Backer G, Basta D, et al. The effect of preoperative penicillin allergy testing on perioperative non-beta-lactam antibiotic use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2018;39(6):420–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Picard M, Robitaille G, Karam F, et al. Cross-reactivity to cephalosporins and carbapenems in penicillin-allergic patients: Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(8):2722–38 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lam PW, Tarighi P, Elligsen M, et al. Self-reported beta-lactam allergy and the risk of surgical site infection: A retrospective cohort study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adult Cardiac Surgery Database 2017. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Published 2020, Available from: https://www.sts.org/registries-research-center/sts-national-database/adult-cardiac-surgery-database. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- 19.Blumenthal KG, Huebner EM, Fu X, Li Y, Bhattacharya G, Levin AS, et al. Risk-based pathway for outpatient penicillin allergy evaluations. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(7):2411–4 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ASA Physical Status Classification System. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Published October 2019, Available at https://www.asahq.org/standards-and-guidelines/asa-physical-status-classification-system. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- 21.Wyles CC, Hevesi M, Osmon DR, et al. 2019 John Charnley Award: Increased risk of prosthetic joint infection following primary total knee and hip arthroplasty with the use of alternative antibiotics to cefazolin: the value of allergy testing for antibiotic prophylaxis. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-B(6_Supple_B):9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zagursky RJ, Pichichero ME. Cross-reactivity in beta-lactam allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(1):72–81 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuhlen JL Jr., Camargo CA Jr., Balekian DS, et al. Antibiotics are the most commonly identified cause of perioperative hypersensitivity reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(4):697–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe M, Suzuki H, Nomura S, et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection in emergency colorectal surgery: A retrospective analysis. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2014;15(3):256–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolfson AR, Huebner EM, Blumenthal KG. Acute care beta-lactam allergy pathways: approaches and outcomes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123(1):16–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, Bittl JA, Bridges CR, Byrne JG, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124(23):e652–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park M, Markus P, Matesic D, et al. Safety and effectiveness of a preoperative allergy clinic in decreasing vancomycin use in patients with a history of penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(5):681–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDanel DL, Azar AE, Dowden AM, et al. Screening for beta-lactam allergy in joint arthroplasty patients to improve surgical prophylaxis practice. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(9S):S101–S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blumenthal KG, Lu N, Zhang Y, et al. Risk of meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile in patients with a documented penicillin allergy: Population based matched cohort study. BMJ. 2018;361:k2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blumenthal KG, Lu N, Zhang Y, et al. Recorded penicillin allergy and risk of mortality: A population-based matched cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1685–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solensky R Penicillin allergy as a public health measure. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):797–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerace KS, Phillips E. Penicillin allergy label persists despite negative testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(5):815–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaisman A, McCready J, Hicks S, et al. Optimizing preoperative prophylaxis in patients with reported beta-lactam allergy: A novel extension of antimicrobial stewardship. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(9):2657–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, et al. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: A review. JAMA. 2019;321(2):188–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blumenthal KG, Li Y, Banerji A, et al. The Cost of Penicillin Allergy Evaluation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(3):1019–27 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]