Abstract

Passiflora edulis, also known as passion fruit, is widely distributed in tropical and subtropical areas of the world and becomes popular because of balanced nutrition and health benefits. Currently, more than 110 phytochemical constituents have been found and identified from the different plant parts of P. edulis in which flavonoids and triterpenoids held the biggest share. Various extracts, fruit juice and isolated compounds showed a wide range of health effects and biological activities such as antioxidant, anti-hypertensive, anti-tumor, antidiabetic, hypolipidemic activities, and so forth. Daily consumption of passion fruit at common doses is non-toxic and safe. P. edulis has great potential development and the vast future application for this economically important crop worldwide, and it is in great demand as a fresh product or a formula for food, health care products or medicines. This mini-review aims to provide systematically reorganized information on physiochemical features, nutritional benefits, biological activities, toxicity, and potential applications of leaves, stems, fruits, and peels of P. edulis.

Keywords: Passiflora edulis, passion fruit, polyphenols, nutritional components, antioxidant activities

Introduction

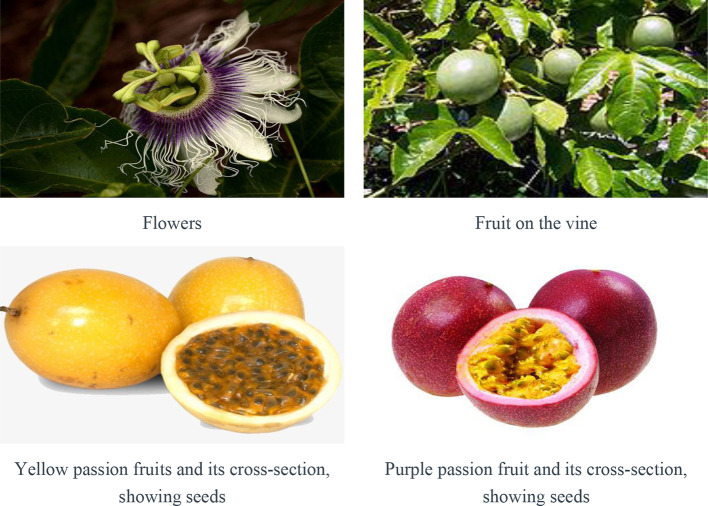

The genus Passiflora, comprising about 500 species, is the largest in family Passifloraceae. Among which, the Passiflora edulis are stands out because of its economic and medicinal importance. (Dhawan et al., 2004). It is widely planted in tropical and subtropical regions in several parts of the world, especially in South America, Caribbean, south Florida, South Africa, and Asia (Zhang et al., 2013; Yuan et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2018). There are seven varieties provided in The Plant List including P. edulis Sims, P. edulis f. edulis, P. edulis f. flavicarpa O. Deg., P. edulis var. kerii (Spreng.) Mast., P. edulis var. pomifera (M. Roem.) Mast., P. edulis var. pomifera (M. Roem.) Mast., P. edulis var. rubricaulis (Jacq.) Mast., and P. edulis var. verrucifera (Lindl.) Mast (The Plant List, 2013). Among them, the yellow-fruited P. edulis f. flavicarpa O. Deg. and the purple-fruited type, P. edulis Sims are the two main and common varieties with considerable economic importance (Zucolotto et al., 2009; Cazarin et al., 2016). The yellow passion fruit is 6–12 cm long and 4–7 cm in diameter. The peel is bright yellow, hard, and thick. The seeds are brown. The pulp is acidic and has a strong aromatic flavor. The purple passion fruit is relatively small in size (4–9 cm long and 3.5–7 cm in diameter). Its peel is purple and seed is black (Narain et al., 2010). Their relevant pictures are listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowers, leaves, and fruits of P. edulis (https://image.baidu.com/).

In recent years, with the considerable work done on P. edulis development, there has been an increasing interest to utilize passion fruit for human consumption due to the eating quality of its fruits, juiciness, attractive nutritional values, essential health benefits, and the people’s choice (Cazarin et al., 2016; Lima et al., 2016; Pereira et al., 2019). Passion fruit, also well known as “the king of fruits”, “maracujá”, “love fruit”, and “fruitlover”, is frequently eaten freshly or squeezed for juice. Meanwhile, a range of products made with passion fruit has been developed including cake, ice cream, jam, jelly, yoghurt, compound beverage, tea, wine, vinegar, soup-stock, condiment sauce, and so on. Passion fruit is also used as traditional folk medicines and cosmetic moisturizing agent in many countries (Xu et al., 2016). In China, the purple passion fruit has been adapted for the cultivation in the warm climate of Jiangsu, Fujian, Taiwan, Hunan, Guangdong, Hainan, Guangxi, Guizhou, Yunnan, and so forth. The purple passion fruit consumption occurs mainly in the form of fresh fruit and fruit juice. According to ZhongHuaBenCao (Simplified Chinese: 中华本草) records, it is sweet, sour in flavour, and highly aromatic, and acts on the heart and large intestine meridians. ZhongHuaBenCao recommends its dosage between 10 and 15 g when taken orally as decoct soup for treatment of cough, hoarseness, constipation, dysmenorrhea, arthralgia, dysentery, insomnia, and so forth. In Brazil, the yellow passion fruit is most commonly used for the preparation of soft drinks and as a remedy in folk medicine, like juices nectars, tinctures or tablets. Today, other parts of P. edulis have also been developed and utilized in many countries. The leaves of P. edulis with highly appreciated and pleasant taste are widely used as sedatives or tranquilizers in the United States and European countries. The flowers are large and beautiful, and can be used as garden ornamental plants. The peels, characterized by high levels of polyphenols, fibers and trace elements, have been widely used for making wine or tea, cooking dishes, extracting pectin and medicinal ingredients, and processing feed. The seeds are edible, and high in protein and oil (mainly composed of linoleic acid, oleic acid, and palmitic acid).

Apart from being a food item, a variety of pharmaceutical products based on ingredients have also be developed and used in folk medicine. The principal components of P. edulis include polyphenols, triterpenes, and its glycosides, carotenoids, cyanogenic glycosides, polysaccharides, amino acids, essential oils, microelements, and so forth (Xu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Yuan et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2018). Among these compounds, the most reported are luteolin, apigenin, and quercetin derivatives. Most importantly, passion fruit contains nutritionally valuable compounds like vitamin C, dietary fiber, B vitamins, niacin, iron, phosphorus, and so forth. A wide range of in vitro and in vivo pharmacological studies have revealed various promising bioactivities of P. edulis, such as antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, anti-hypertensive, hepatoprotective and lung-protective activities, anti-diabetic, sedative, antidepressant activity, and anxiolytic-like actions (Nayak and Panda, 2012; Kinoshita et al., 2013; Silva et al., 2015; Dzotam et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Panelli et al., 2018). Most of these effects are consistent with those observed for P. edulis in traditional and folk medicine, and these pharmacological actions are thought to be mostly mediated via the existed bioactive components including polyphenol, triterpenes, and polysaccharides. Several researchers have reviewed the botany, chemistry, and pharmacological reports of the Passiflora genus (Dhawan et al., 2004; Corrêa et al., 2016). However, to date, no comprehensive review concerning the information on the chemical and biological properties of P. edulis is available.

In this mini-review, we intend to systematically summarize the recent advances in knowledge about chemical and biological activities of different parts of P. edulis (fruit, stems, leaves, and peel). The extraction methods and purification procedures for polysaccharides, processing passion fruit for formulation and production of food product is also reviewed. Future research directions on how to better utilize and develop passion fruit are suggested.

Physicochemical and Structural Features

The major nutrient components of P. edulis include dietary fiber, carbohydrates, lipids, carboxylic acids, polyphenols, volatile compound, protein and amino acids, vitamins, mineral, and so forth. (Table 1). To date, more than 110 kinds of chemical constituents have been isolated and identified from the P. edulis. Among them, flavonoids, triterpenoids, and carotenoids are the primary types. Methods for determination of main chemical components from P. edulis are shown in Table 2. The main monomeric compounds are summarized and compiled in Table 3.

Table 1.

Nutritional composition of purple and yellow passion fruit juice (USDA Food Composition Databases, 2019).

| Nutrient | Unit | Purple passion fruit juice, raw | Yellow passion fruit juice, raw |

|---|---|---|---|

| Value per 100 g | Value per 100 g | ||

| Proximates | |||

| Water | g | 85.62 | 84.21 |

| Energy | kcal | 51 | 60 |

| Protein | g | 0.39 | 0.67 |

| Total lipid (fat) | g | 0.56 | 0.18 |

| Carbohydrate, by difference | g | 13.6 | 14.45 |

| Fiber, total dietary | g | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Sugars, total | g | 13.4 | 14.25 |

| Minerals | |||

| Calcium, Ca | mg | 4 | 4 |

| Iron, Fe | mg | 0.24 | 0.36 |

| Magnesium, Mg | mg | 17 | 17 |

| Phosphorus, P | mg | 13 | 25 |

| Potassium, K | mg | 278 | 278 |

| Sodium, Na | mg | 6 | 6 |

| Zinc, Zn | mg | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| Copper, Cu | mg | 0.053 | 0.05 |

| Selenium, Se | µg | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Vitamins | |||

| Vitamin C, total ascorbic acid | mg | 29.8 | 18.2 |

| Thiamin | mg | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Riboflavin | mg | 0.131 | 0.101 |

| Niacin | mg | 1.46 | 2.240 |

| Vitamin B-6 | mg | 0.05 | 0.060 |

| Folate, DFE | µg | 7 | 8 |

| Vitamin B-12 | µg | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Vitamin A, RAE | µg | 36 | 47 |

| Vitamin A, IU | IU | 717 | 943 |

| Vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) | mg | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Vitamin D (D2 + D3) | µg | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Vitamin D | IU | 0 | 0 |

| Vitamin K (phylloquinone) | µg | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Lipids | |||

| Fatty acids, total saturated | g | 0.004 | 0.015 |

| Fatty acids, total monounsaturated | g | 0.006 | 0.022 |

| Fatty acids, total polyunsaturated | g | 0.029 | 0.106 |

Table 2.

Methods for determination of chemical components of P. edulis.

| Chemical components | Plant part | Location and number of geno-type | Better methods | Major findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenol | Pulp | Brazil, yellow passion fruit | QuEChERS method combined with C18 as d-SPE clean-up sorbent/UHPLC-MS-MS | Quercetin, rutin, 4-hydroxybenzoic, chlorogenic, ferulic, vanillic, caffeic, trans-cinammic, and p-coumaric acids, and the most abundant phenolic components were quercetin and vanillic acid. | Rotta et al., 2019 |

| Volatile compounds | Pulp | Brazil, yellow passion fruit | Dynamic headspace/GC-MS and GC-O analysis | 64 volatile compounds, and mainly include esters, alcohols, terpenes, aldehydes, and ketones, and so forth. | Janzantti et al., 2012 |

| Carbohydrate | Pulp | France, passion fruit (unknown) | Acid hydrolysis, NaOH (2 M), Fehling solution | 13.70 g glucose equivalent/100 g | Septembre-Malaterre et al., 2016 |

| Carotenoid | Pulp | France, passion fruit (unknown) | UV-vis spectrophotometry at 450 nm | 3.83 mg β-carotene equivalent/100 g | Septembre-Malaterre et al., 2016 |

| Vitamin C | Pulp | France, passion fruit (unknown) | 2,6-dichloro-phenol-indophenol titrimetric method | 44.40 mg ascorbic acid equivalent/100 g | Septembre-Malaterre et al., 2016 |

| Polyphenol | Pulp | France, passion fruit (unknown) | Folin-Ciocalteu assay | 286.60 mg gallic acid equivalent/100 g | Septembre-Malaterre et al., 2016 |

| Flavonoid | Pulp | France, passion fruit (unknown) | Colorimetric assay | 70.10 mg quercetin equivalent/100 g | Septembre-Malaterre et al., 2016 |

| Polyphenol | Fresh green leaves | Sri Lanka, passion fruit (unknown) | 70% (vol/vol) acetone/alkaline hydrolysis/HPLC | The total soluble, insoluble-bound phenolic compounds and total flavonoid from the extracts were 511.20 mmol/g (gallic acid equivalent), 66.62 mmol/g (gallic acid equivalent), and 111.69 mmol/g (rutin equivalent). | Gunathilake et al., 2018a |

| Polyphenol | Seeds | Brazil, yellow passion fruit | 70% ethanol at 80°C for 30 min | 31.20 mg/g (gallic acid equivalent), and the major component was piceatannol (36.80 mg/g). | de Santana et al., 2017 |

| Polyphenol | Peel | Brazil, yellow passion fruit | Ultrasound-assisted or Pressurized solvent extraction (ethanol at 60:40)/LC-DAD-ESI-MS | 4.67 mg/g (gallic acid equivalent). and mainly include orientin, orientin-7-O-glucoside, vitexin and isoorientin. | de Souza et al., 2018 |

| Polyphenol | Ripe fruits | Panama, passion fruit (unknown) | Methanol | 81 mg/100 g (Gallic acid equivalent) fresh weight | Murillo et al., 2012 |

| Oil | Seeds | Brazil, yellow passion fruit | SE using n-hexane as solvent | High tocopherol and fatty acid like palmitic, stearic, oleic, linoleic, α-Linolenic, behenic, caprylic, and aproic | Pereira et al., 2019 |

| Bound terpenoids | Juice | Australia, purple passion fruit | Almond glycosidase hydrolysis with C18 isolates (MeOH elution), HRGC-MS | 15 C13 norterpenoid aglycons, and the main terpenoids are 4-hydroxy-β-ionol, 4-oxo- β -ionol, 4-hydroxy-7,8-dihydro-β-ionol, 4-oxo-7,8-dihydro- β -ionol, 3-oxo-α-ionol, isomeric 3-oxoretro-α-ionols, 3-oxo-7,8-dihydro -α-ionol, 3-hydroxy-1,1, 6-trimethyl-1,2,3, 4-tetrahydronaphthalene, vomifoliol, and dehydrovomifoliol, and so forth. | Winterhalter, 1990 |

Table 3.

Chemical Components of P. edulis.

| NO. | Compounds | CAS number | Formula | Resources | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | |||||

| 1 | Quercetine | 117-39-5 | C15H10O7 | A | Lutomski et al., 1975 |

| 2 | Rutin | 153-18-4 | C27H30O16 | A | Lutomski et al., 1975 |

| 3 | Vitexina | 3681-93-4 | C21H20O10 | A | Lutomski et al., 1975 |

| 4 | Isoorientin | 4261-42-1 | C21H20O11 | A | Lutomski et al., 1975 |

| 5 | Saponarin | 20310-89-8 | C27H30O15 | A | Lutomski et al., 1975 |

| 6 | Homovitexin | 38953-85-4 | C21H20O10 | A | Lutomski et al., 1975 |

| 7 | Luteolin-6-C-chinovoside | 132368-05-9 | C21 H20 O10 | A | Mareck et al., 1991 |

| 8 | Luteolin-6-C-fucoside | 138810-81-8 | C21 H20 O10 | A | Mareck et al., 1991 |

| 9 | Orientin | 28608-75-5 | C21 H20 O11 | A | Moraes et al., 1997 |

| 10 | Myrtillin | 50986-17-9 | C21 H21 O12+ | A | Kidoey et al., 1997 |

| 11 | Petunidin 3-glucoside | 71991-88-3 | C22 H23 O12+ | A | Kidoey et al., 1997 |

| 12 | Cyanidin 3-glucoside | 47705-70-4 | C21 H21 O11+ | A | Kidoey et al., 1997 |

| 13 | Callistephin | 47684-27-5 | C21 H21 O10+ | A | Kidoey et al., 1997 |

| 14 | Cyanidin 3-(6″-malonylglucoside) | 171828-62-9 | C24 H23 O14+ | A | Kidoey et al., 1997 |

| 15 | Pelargonidin 3-(6″-malonylglucoside) | 165070-68-8 | C24 H23 O13+ | A | Kidoey et al., 1997 |

| 16 | Delphinidin 3-(6″-malonylglucoside) | 478693-96-8 | C24 H23 O15+ | A | Kidoey et al., 1997 |

| 17 | 1-Benzopyrylium, 3-[[6-O-(carboxyacetyl)-β-D-glucopyranosyl]oxy]-2-(3,4-dihydroxy-5-methoxyphenyl)-5,7-dihydroxy- | 687619-89-2 | C25 H25 O15+ | A | Kidoey et al., 1997 |

| 18 | Idein | 142506-26-1 | C21 H21 O11+ | A | Chang and Su, 1998 |

| 19 | Luteolin | 491-70-3 | C15 H10 O6 | B | Coleta et al., 2006 |

| 20 | Lonicerin | 25694-72-8 | C27 H30 O15 | B | Coleta et al., 2006 |

| 21 | Vitexin, 4′-rhamnoside | 32426-34-9 | C27 H30 O14 | C | Zhou et al., 2009 |

| 22 | Spinosin | 72063-39-9 | C28 H32 O15 | B | Zucolotto et al., 2009 |

| 23 | Vicenin | 23666-13-9 | C27 H30 O15 | B | Zucolotto et al., 2009 |

| 24 | 6,8-di-C-glycosylchrysin | 850621-76-0 | C27 H30 O14 | B | Zucolotto et al., 2009 |

| 25 | Chrysin 6-C-β-rutinoside | 1488426-52-3 | C27 H30 O13 | B | Zhang et al., 2013 |

| 26 | Chrysin 7-glucoside | 31025-53-3 | C21 H20 O9 | D | Xu et al., 2013 |

| 27 | 7-[[4-O-(6-Deoxy-α-L-mannopyranosyl)-β-D-glucopyranosyl]oxy]-5-hydroxy-2-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one | 378782-33-3 | C27 H30 O13 | D | Xu et al., 2013 |

| 28 | Luteolin 8-C-β-digitoxopyranoside | 951126-36-6 | C21 H20 O9 | D | Xu et al., 2013 |

| 29 | 7-De-O-methylaciculatin | 1355022-31-9 | C21 H20 O8 | D | Xu et al., 2013 |

| 30 | 8-C-β-D-Boivinopyranosylapigenin | 1355022-34-2 | C21 H20 O8 | D | Xu et al., 2013 |

| 31 | Luteolin 8-C-β-digitoxopyranosyl-4′-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | 1402209-61-3 | C27 H30 O14 | D | Xu et al., 2013 |

| 32 | Luteolin 8-C-β-boivinopyranoside | 1402209-62-4 | C21 H20 O9 | D | Xu et al., 2013 |

| 33 | Chrysin-8-C-(2″-O-6-deoxy-α-D-glucopyranosyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside | 2171100-31-3 | C27 H30 O13 | E | Hu et al., 2018 |

| Triterpenoids | |||||

| 34 | Passiflorin | 1392-82-1 | C37 H60 O12 | A | Bombardelli et al., 1975 |

| 35 | Cyclopassifloic acid E | 301540-74-9 | C31 H52 O8 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000b |

| 36 | Cyclopassifloic acid F | 301540-76-1 | C31 H52 O7 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000b |

| 37 | Cyclopassifloic acid G | 301540-77-2 | C31 H52 O7 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000b |

| 38 | Cyclopassifloside VII | 301540-80-7 | C37 H62 O13 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000b |

| 39 | Cyclopassifloside VIII | 301540-81-8 | C37 H62 O12 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000b |

| 40 | Cyclopassifloside X | 301540-82-9 | C37 H62 O12 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000b |

| 41 | Cyclopassifloside IX | 301644-33-7 | C43 H72 O17 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000b |

| 42 | Cyclopassifloside XI | 301644-34-8 | C43 H72 O17 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000b |

| 43 | Passifloric acid | 64147-49-5 | C31 H50 O7 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000a |

| 44 | Cyclopassifloic acid B | 292167-35-2 | C31 H52 O6 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000a |

| 45 | Cyclopassifloic acid C | 292167-36-3 | C31 H52 O7 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000a |

| 46 | Cyclopassifloside IV | 292167-41-0 | C37 H62 O12 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000a |

| 47 | Cyclopassifloside V | 292167-42-1 | C43 H72 O17 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000a |

| 48 | Cyclopassifloside VI | 292167-43-2 | C36 H58 O11 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000a |

| 49 | Cyclopassifloic acid D | 292167-37-4 | C30 H48 O6 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000a |

| 50 | Cyclopassifloside II | 292167-39-6 | C37 H62 O11 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000a |

| 51 | Cyclopassifloside I | 292167-38-5 | C37 H62 O12 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000a |

| 52 | Cyclopassifloside III | 292167-40-9 | C43 H72 O16 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000a |

| 53 | Cyclopassifloic acid A | 292167-34-1 | C31 H52 O7 | D | Yoshikawa et al., 2000a |

| 54 | 3β,16β-diacetoxyurs-12-ene | 920957-33-1 | C34 H54 O4 | F | Yoshikawa et al., 2000a |

| 55 | (3β,5α,8α,22E)-5,8-Epidioxyergosta-6,22-dien-3-ol | 2061-64-5 | C28 H44 O3 | C | Zhou et al., 2009 |

| 56 | (31R)-31-O-Methylpassiflorine | 1491979-55-5 | C38 H62 O12 | B | Zhang et al., 2013 |

| 57 | (31S)-31-O-Methylpassiflorine | 1491979-58-8 | C38 H62 O12 | B | Zhang et al., 2013 |

| 58 | (31R)-Passiflorine | 1492023-84-3 | C37 H60 O12 | B | Zhang et al., 2013 |

| 59 | (31S)-Passiflorine | 1492023-87-6 | C37 H60 O12 | B | Zhang et al., 2013 |

| 60 | Cyclopassifloside XII | 1595294-85-1 | C37 H60 O12 | D | Wang et al., 2013 |

| 61 | Cyclopassifloside XIII | 1595294-86-2 | C43 H72 O17 | D | Wang et al., 2013 |

| 62 | β-Sitostenone | 1058-61-3 | C29 H48 O | B | Yuan et al., 2017 |

| Alkaloids | |||||

| 63 | Harmidine | 304-21-2 | C13 H14 N2 O | A | Lutomski et al., 1975 |

| 64 | Harmine | 442-51-3 | C13 H12 N2 O | A | Lutomski et al., 1975 |

| 65 | Harmane | 486-84-0 | C12 H10 N2 | A | Lutomski et al., 1975 |

| 66 | Harmol | 487-03-6 | C12 H10 N2 O | A | Lutomski et al., 1975 |

| 67 | N-trans-Feruloyltyramine | 66648-43-9 | C18 H19 N O4 | B | Yuan et al., 2017 |

| 68 | cis-N-Feruloyltyramine | 80510-09-4 | C18 H19 N O4 | B | Yuan et al., 2017 |

| Sulforaphanes | |||||

| 69 | 3-(Methylthio)-1-hexanol; 3-(Methylthio)hexanol | 51755-66-9 | C7 H16 O S | A | Winter et al., 1976 |

| 70 | cis-2-Methyl-4-propyl-1,3-oxathiane | 59323-76-1 | C8 H16 O S | A | Winter et al., 1976 |

| 71 | (±)-trans-2-Methyl-4-propyl-1,3-oxathiane | 59324-17-3 | C8 H16 O S | A | Winter et al., 1976 |

| 72 | Ethanethioic acid, S-[1-[2-(acetyloxy)ethyl]butyl] ester | 136954-25-1 | C10 H18 O3 S | A | Engel and Tressl, 1991 |

| 73 | Butanoic acid, 3-[(1-oxobutyl)thio]hexyl ester | 136954-26-2 | C14 H26 O3 S | A | Engel and Tressl, 1991 |

| 74 | Hexanoic acid, 3-[(1-oxohexyl)thio]hexyl ester | 136954-27-3 | C18 H34 O3 S | A | Engel and Tressl, 1991 |

| Carotenoids | |||||

| 75 | Violaxanthin | 126-29-4 | C40 H56 O4 | A | Mercadante et al., 1998 |

| 76 | β-Cryptoxanthin | 472-70-8 | C40 H56 O | A | Mercadante et al., 1998 |

| 77 | Neurosporene | 502-64-7 | C40 H58 | A | Mercadante et al., 1998 |

| 78 | Lycopene | 502-65-8 | C40 H56 | A | Mercadante et al., 1998 |

| 79 | Mutatochrome | 515-06-0 | C30 H40 O2 | A | Mercadante et al., 1998 |

| 80 | β-Citraurin | 650-69-1 | C30H40O2 | A | Mercadante et al., 1998 |

| 81 | Prolycopene | 2361-24-2 | C40 H56 | A | Mercadante et al., 1998 |

| 82 | β-Carotene | 7235-40-7 | C40 H56 | A | Mercadante et al., 1998 |

| 83 | Phytoene | 13920-14-4 | C40 H64 | A | Mercadante et al., 1998 |

| 84 | Neoxanthin | 14660-91-4 | C40 H56 O4 | A | Mercadante et al., 1998 |

| 85 | Phytofluene | 27664-65-9 | C40 H62 | A | Mercadante et al., 1998 |

| 86 | Antheraxanthin | 68831-78-7 | C40 H56 O3 | A | Mercadante et al., 1998 |

| 87 | ζ-Carotene | 72746-33-9 | C40 H60 | A | Mercadante et al., 1998 |

| Other compounds | |||||

| 88 | Prunasin | 99-18-3 | C14 H17 N O6 | G | Spencer and Seigler, 1983 |

| 89 | Benzyl alcohol O-α-L-arabinopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glycopyranoside | 148031-67-8 | C18 H26 O10 | A | Chassagne et al., 1996 |

| 90 | 3-Methyl-2-buten-1-yl 6-O-α-L-arabinopyranosyl-β-D-glucopyranoside | 175737-84-5 | C16 H28 O10 | A | Chassagne et al., 1996 |

| 91 | 1-Ethenyl-1,5-dimethyl-4-hexen-1-yl 6-O-α-L-arabinopyranosyl-β-D-glucopyranoside | 175892-12-3 | C21 H36 O10 | A | Chassagne et al., 1996 |

| 92 | 3-Oxo-α-ionol | 34318-21-3 | C13 H20 O2 | A | Herderich and Winterhalter, 1991 |

| 93 | Benzoic acid, 2-[[2,3,4-tri-O-acetyl-6-O-(2,3,4-tri-O-acetyl-6-deoxy-α-L-mannopyranosyl)-β-D-glucopyranosyl]oxy]-, methyl ester | 191273-45-7 | C32 H40 O18 | A | Chassagne et al., 1997 |

| 94 | Benzoic acid, 2-[[6-O-(6-deoxy-α-L-mannopyranosyl)-β-D-glucopyranosyl]oxy]-, methyl ester | 191273-46-8 | C20 H28 O12 | A | Chassagne et al., 1997 |

| 95 | Cyanogenic β-rutinoside | 215583-49-6 | C20 H27 N O10 | A | Chassagne and Crouzet, 1998 |

| 96 | Phenylmethyl β-D-allopyranoside | 354807-69-5 | C13 H18 O6 | A | Christensen and Jaroszewski, 2001 |

| 97 | Passiedulin | 354814-09-8 | C14 H17 N O6 | A | Seigler et al., 2002 |

| 98 | Sambunigrin | 99-19-4 | C14 H17 N O6 | A | Seigler et al., 2002 |

| 99 | Benzeneacetonitrile, α-(β-D-allopyranosyloxy)-, (αS)- | 474075-97-3 | C14 H17 N O6 | A | Seigler et al., 2002 |

| 100 | Passiflactone | 1130942-01-6 | C8 H8 O4 | A | Lu et al., 2007 |

| 101 | Amygdalin | 29883-15-6 | C20 H27 N O11 | B | Zhang et al., 2013 |

| 102 | Roseoside | 54835-70-0 | C19 H30 O8 | B | Zhang et al., 2013 |

| 103 | p-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 99-96-7 | C7 H6 O3 | B | Yuan et al., 2017 |

| 104 | Vanillic acid | 121-34-6 | C8 H8 O4 | B | Yuan et al., 2017 |

| 105 | Syringic acid | 530-57-4 | C9 H10 O5 | B | Yuan et al., 2017 |

| 106 | (+)-Syringaresinol | 21453-69-0 | C22 H26 O8 | B | Yuan et al., 2017 |

| 107 | 4-Acetyl-3,5-dimethoxy-p-quinol | 211192-56-2 | C10 H12 O5 | B | Yuan et al., 2017 |

| 108 | α-Tocoquinone | 7559-04-8 | C29 H50 O3 | A | Hu et al., 2018 |

| 109 | Prulaurasin | 138-53-4 | C14 H17 N O6 | A | Hu et al., 2018 |

| 110 | Citrusin A | 105279-09-2 | C26 H34 O12 | A | Hu et al., 2018 |

| 111 | Citrusin B | 105279-10-5 | C27 H36 O13 | A | Hu et al., 2018 |

| 112 | Citrusin G | 2173403-45-5 | C28 H38 O12 | A | Hu et al., 2018 |

| 113 | trans-Coniferin | 124151-33-3 | C16 H22 O8 | A | Hu et al., 2018 |

| 114 | Icariside E5 | 126176-79-2 | C26 H34 O11 | A | Hu et al., 2018 |

| 115 | Alangioside A | 156199-49-4 | C19 H34 O8 | A | Hu et al., 2018 |

| 116 | Longifloroside B | 175556-09-9 | C27 H36 O13 | A | Hu et al., 2018 |

| 117 | Hyuganoside IIIa | 838845-07-1 | C26 H34 O12 | A | Hu et al., 2018 |

| 118 | Hyuganoside IIIb | 838845-08-2 | C26 H34 O12 | A | Hu et al., 2018 |

| 119 | 3,5-Dimethoxy-1-(3-hydroxypropen-1-yl)phenyl 4-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1″→6′)-β-D-glucopyranoside | 2171100-32-4 | C23 H34 O13 | A | Hu et al., 2018 |

A: fruits; B: leaves; C: stems; D: leaves and stems; E: peels; F: roots; G: leaves and fruits.

Nutritional Composition

Table 1 lists the nutritional composition of purple and yellow passion fruit juice reported from the USDA Food Composition Database. The data show evidence that the purple and yellow passion fruit juice contain a high percentage of carbohydrate, Vitamin A, Vitamin C, minerals, and fiber. In general, the nutritional composition content in purple passion fruit was basically the same as that in yellow variety. In general, the passion fruit has a potential to become a functional food.

Pectin, Fiber, and Polysaccharides

Pectin, fiber, and polysaccharides are the most common functional ingredients in food products and exert a strong positive influence on human health. The contents of pectin, crude fiber and polysaccharides are 12.5%, 22.1%, and 20.62%, respectively (Wen et al., 2008). The seed of P. edulis is rich in insoluble dietary fiber (64.1%). After defatting, the insoluble fiber-rich fractions (84.9%–93.3%) including cellulose, pectic substances, and hemicellulose become the predominant components (Chau and Huang, 2003). GC-MS showed that polysaccharides from the peel of yellow passion fruit are composed of galacturonic acid (44.2%), arabinose (11.8%), glucose (11.8%), maltotriose (10.6%), mannose (9.0%), galactose (6.1%), xylose (3.6%), ribose (1.3%) and fucose (1.6%), and so forth. (Silva et al., 2012). Meanwhile, yellow passion fruit rind is a good source of naturally low-methoxyl pectin. Polysaccharide from purple passion fruit peel is mainly composed of galacturonic acid (80.32%), glucose (4.65%), ribose (4.41%), galactose (3.84%), arabinose (3.53%), mannose (1.34%), xylose (0.72%) and rhamnose (0.17%), and so forth. We found (1→4)-linked galacturonic acid is the main component of polysaccharides from yellow and purple passion fruit. Diverse studies have demonstrated that pectin and fibers from P. edulis peel can effectively eliminate free radicals such as DPPH and ABTS (Dos Reis et al., 2018), reduce cholesterol and blood glucose levels (Lacerda-Miranda et al., 2016), and obviously inhibit the growth of sarcoma180 (Silva et al., 2012), and so forth. Thus, the passion fruit peel may be utilized in the development of new fiber-rich healthy food products.

Protein and Amino Acids

The total protein content from fruit pulp of passion fruit is 0.80 mg/g (Araujo et al., 2003). Importantly, some proteins in passion fruit have promising antifungal properties. For example, Pe-AFP1 (5.0 kDa), a 2S-albumin-protein-like peptide purified from the seeds of passion fruit, is found to be able to inhibit the growth of filamentous fungi Trichoderma harzianum, Fusarium oxysporum, and Aspergillus fumigatus with a respective IC50 values of 32, 34, and 40 μg/ml (Pelegrini et al., 2006). Free amino acids isolated from purple passion fruit mainly include leucine, valine, tyrosine, proline, threonine, glycine, aspartic acid, arginine, and lysine. Among them, lysine, threonine, leucine, and valine are indispensable amino acids for growth.

Volatile Components

Volatile components should be the aromatic ingredients of passion fruit, and they also have anti-oxidative activity. The esters (59.24%), aldehydes (15.27%), ketones (11.70%), alcs. (6.56%), terpenes, and other miscellaneous compounds have been proven to exist in passion fruit (Narain et al., 2004). GC and GC-MS analysis revealed that the major volatile constituents of fruit shell of P. edulis Sims are 2-tridecanone (62.1%), (9Z)-octadecenoic acid (16.6%), 2-pentadecanone (6.2%), hexadecanoic acid (3.2%), 2-tridecanol (2.1%), octadecanoic acid (2.0%), and caryophyllene oxide (2.0%) (Arriaga et al., 1997). It is noteworthy that the volatile components changed during maturation.

Lipids

P. edulis seeds contain 20% drying oil, solid fat acid 11.5% (palmitic and stearic acids) and 88.5% liquid acid (linolic and oleic acids). Seeds oil contain high amount of unsaturated fatty acids, and the major unsaturated fatty acids are linoleic acid (69.3%), oleic acid (14.4%), palmitic acid (10.1%), and stearic acid (2.9%) (Rana and Blazquez, 2008). The total content of crude oil in the residue of passion fruit after juice production is ∼24%.

Minerals

Passion fruit is a very refreshing tropical fruit and full of minerals in fruit, juice, peel and seeds, which are known to be effective to human health. For instance, Fe, Zn, Mn, B, Cu, K, N, Ca, P, Mg, S, and Mo of skin and pulp and seeds of passion flower are 150, 41, 40, 25, 10, 3, 0.8, 0.4, 0.21, 0.15, 0.08, 0.08, and 110, 50, 16, 9, 6, 2, 1.4, 0.1, 0.25, 0.15, 0.08, and 0.12 ppm, respectively. We can consider passion fruit plant leaves as good resources of calcium and zinc due to the high content of both minerals. In the youngest leaves, the contents of N, P, K, and Zn are relatively high while the Ca, Mg, B, Cl, and Mn are relatively low (Freitas et al., 2007). Table 1 shows passion fruit juice is a source of minerals that naturally rich in Ca, Mn, P, and K, and so forth. However, the information on harmful elements of passion fruit is rather scarce.

Flavonoids

The passion fruit pulp is a famous food source of flavonoids, which contains 158.0 μg/ml of total flavonoids, 16.2 μg/ml of isoorientin (Zeraik and Yariwake, 2010) and 0.42 μg/g of quercetin (Rotta et al., 2019). The aerial parts of P. edulis extracted by reflux with 40% ethanol contain 0.90% of apigenin. So far, 33 flavonoids have been identified in various parts of P. edulis (Lutomski et al., 1975; Mareck et al., 1991; Moraes et al., 1997; Chang and Su, 1998; Xu et al., 2013). Among them, the major flavonoids identified from P. edulis are vitexin, isovitexin, isoorientin, apigenin, quercetine, luteolin, and their derivatives, which represent important classes of effective compounds in P. edulis regarding their various biological and pharmacological properties (Deng et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013).

Triterpenoids

Twenty nine triterpenoids varying in chemical structures have been isolated from fruits, leaves, stems, and roots of P. edulis (Bombardelli et al., 1975; Yoshikawa et al., 2000a; Yoshikawa et al., 2000b; Zhou et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2013; Yuan et al., 2017). Cycloartane triterpenoids have showed the significant protective effects against damage of PC12 cell induced by glutamate, which can be used for the treatment of neurodegenerative disease (Xu et al., 2016). Cycloartane triterpenoids cyclopassiflosides IX and XI at 50 mg/kg displayed antidepressant-like effect (Wang et al., 2013).

Alkaloids

Alkaloids including harmidine, harmine, harmane, harmol, N-trans-feruloyltyramine, and cis-N-feruloyltyramine have been found in fruits and leaves of P. edulis (Lutomski et al., 1975; Yuan et al., 2017). Harmine, a fluorescent harmala alkaloid, can reversibly inhibit monoamine oxidase A and angiogenesis and suppress tumor growth. Meanwhile, it showed anti-inflammatory activity by significantly inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway (Liu et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018).

Sulforaphanes and Carotenoids

Six sulforaphanes and 13 carotenoids have been isolated and identified in fruits of P. edulis (Winter et al., 1976; Engel and Tressl, 1991; Mercadante et al., 1998). Carotenoids from vegetables and fruit play important roles in physiological functions, and thus have health benefits including anti-obesity, antidiabetic, and anticancer activities, and so forth. (Chuyen and Eun, 2017).

Biological Activities

In China, South America, India, and so forth., P. edulis is commonly used as a tonic, digestive, sedative, diuretic, antidiarrheal, insecticide in traditional medicine for the treatment of cough, dry throat, constipation, insomnia, dysmenorrhea, colic infants, joint pain, and dysentery, and so forth. (Dhawan et al., 2004). Modern biochemical and pharmacological studies confirmed that the purified components and crude extracts from P. edulis showed a wide range of in vitro and in vivo bioactivities (Chau and Huang, 2005; Nayak and Panda, 2012; Kinoshita et al., 2013; Otify et al., 2015; Panchanathan and Rajendran, 2015; Silva et al., 2015; Dzotam et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Ayres et al., 2017; He et al., 2017; Goss et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2018; Mota et al., 2018; Panelli et al., 2018). Table 4 shows the biological activities of main compounds isolated from P. edulis.

Table 4.

Biological activities of compounds isolated from P. edulis ("↓", reduce; "↑", increase).

| Bioactivity | Compound | Experiment | Biological results | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive control | Compound | ||||

| Anti-inflammatory effect | α-Tocopherylquinone | RAW 264.7 cells | IC50 = 34.92 μM, NO production↓ | Hu et al., 2018 | |

| Luteolin-8-C-β-digitoxopyranoside | RAW 264.7 cells | IC50 = 16.12 μM, NO production↓ | Hu et al., 2018 | ||

| Luteolin-8-C-β-boivinopyranoside | RAW 264.7 cells | IC50 = 26.67 μM, NO production ↓ | Hu et al., 2018 | ||

| Isoorientin | Swiss mice | Indomethacin (5 mg/kg), dexamethasone (0.5 mg/kg) | 25 mg/kg ip., leukocytes, neutrophils, mononuclears↓, MPO activity↓ | Zucolotto et al., 2009 | |

| Vicenin-2 | Swiss mice | Indomethacin (5 mg/kg), dexamethasone (0.5 mg/kg) | 25 mg/kg ip., leukocytes, neutrophils, mononuclears↓, MPO activity↓ | Zucolotto et al., 2009 | |

| Spinosin | Swiss mice | Indomethacin (5 mg/kg), dexamethasone (0.5 mg/kg) | 25 mg/kg ip., leukocytes, neutrophils, mononuclears↓, MPO activity↓ | Zucolotto et al., 2009 | |

| Orientin | DMH induced colorectal cancer in rats | 10 mg/kg ip., TNF-α, IL-6, iNOS and COX-2 expression ↓ | Thangaraj and Vaiyapuri, 2017 | ||

| Neuroprotective effects | 1α,3β-dihydroxy-16-keto-24(31)-en-cycloartane | PC12 cells | 0.05-0.42 μM against the glutamate-induced neurotoxicity | Xu et al., 2016 | |

| 31-Methoxyl-passifloic acid | PC12 cells | 0.06-0.23 μM against the glutamate-induced neurotoxicity | Xu et al., 2016 | ||

| Cyclopassifloside II | PC12 cells | 0.08-0.35 μM against the glutamate-induced neurotoxicity | Xu et al., 2016 | ||

| Cyclopassifloside VIII | PC12 cells | 0.06-0.46 μM against the glutamate-induced neurotoxicity | Xu et al., 2016 | ||

| Cyclopassifloside XIV | PC12 cells | 0.08-0.32 μM against the glutamate-induced neurotoxicity | Xu et al., 2016 | ||

| Luteolin | PC12 cells | 50.0 μM, NGF-induced neurite outgrowth ↑ | Xu et al., 2013 | ||

| Piceatannol | mouse embryonic stem cells | 2.5 µM, astrocyte differentiation↑ | Arai et al., 2016 | ||

| Anxiolytic-like effect | Isoorientin | Swiss albino mice | Diazepam (2 mg/kg Ig.) | 40 and 80 mg/kg, time spent in open arms of the elevated plus-maze ↑ | Deng et al., 2010 |

| Luteolin-7-O-[2-rhamnosylglucoside] | Swiss mice | Diazepam (1 mg/kg Ig.) | 30 mg/kg, time spent in the open arms of the elevated plus maze test ↑ | Coleta et al., 2006 | |

| Antidepressant-like effect | Cyclopassiflosides IX | ICR mice | Clomipramine (50 mg/kg) | 50 mg/kg Ig., immobility time in forced swim and tail suspension test reduced by 22.72% and 39.26% | Wang et al., 2013 |

| Cyclopassiflosides XI | ICR mice | Clomipramine (50 mg/kg) | 50 mg/kg Ig., immobility time in forced swim and tail suspension test reduced by 19.16% and 43.12% | Wang et al., 2013 | |

| Sedative-like activity | Isoorientin | Swiss albino mice | Diazepam (2 mg/kg Ig.) | 40 mg/kg and 80 mg/kg, number of spontaneous activities↓ | Deng et al., 2010 |

| Vasorelaxation effect | Piceatannol | Isolated rat thoracic aorta | 30 μM, eNOS expression↑ | Sano et al., 2011; Kinoshita et al., 2013 | |

| Piceatannol | Human EA. hy926 endothelial cells | 20 μM, 48 h, eNOS expression↑ | Kinoshita et al., 2013 | ||

| Scirpusin B | Isolated rat thoracic aorta | 30 μM, endothelium-derived NO↑ | Sano et al., 2011 | ||

| Melanin inhibition and collagen synthesis promotion | Piceatannol | Dermal Cells (SF-TY cells) | 4.5 μM, melanin synthesis↓; 5 μM increased collagen synthesis↑ | Matsui et al., 2010 | |

| Isoorientin | B16 melanoma cells | 100 μM, melanin content (47.2% reduction) ↓ | Zhang et al., 2013 | ||

| Chrysin 6-C-β-rutinoside | B16 melanoma cells | 100 μM, melanin content (47.2% reduction) ↓, MITF, tyrosinase, TRP-1, and TRP-2 proteins levels ↓ | Zhang et al., 2013 | ||

| (6S,9R)-roseoside | B16 melanoma cells | 100 μM, melanin content (37.3% reduction) ↓ | Zhang et al., 2013 | ||

| Antidiabetic activity | Piceatannol | db/db mice | 50 mg/kg, blood glucose levels↓ | Uchida-Maruki et al., 2015 | |

| Piceatannol | Humans | 20 mg/day for 56 days, the insulin sensitivity, BP and HR improvement | Kitada et al., 2017 | ||

| Antioxidant activity | Scirpusin B | DPPH | Trolox | 5-40 μM, DPPH radical scavenging activities | Sano et al., 2011 |

| Piceatannol | DPPH | Trolox | 5-40 μM, DPPH radical scavenging activities | Sano et al., 2011 | |

| Piceatannol | BALB/cByJ Jcl mice | 10 mg/kg Ig., 14 days, number of astrocytes↑ | Arai et al., 2016 | ||

Antioxidant Activity

Large amount studies highlight the potential of passion fruit as a valuable source of natural antioxidants which can eliminate free radicals or inhibit the activity of free radicals, thereby helping the body to maintain an adequate antioxidant status. The antioxidant and radical scavenging activities of the extracts from fruit, seed, peel, leaves, bark of P. edulis have been studied via ABTS (Zas and John, 2017), AAPH, DPPH, FRAP, ORAC, HOCI scavengers and ferrous ions assays in vitro, as well as several in vivo experiments (Rotta et al., 2019). The results showed that aqueous, ethanol, polyphenol-rich in particular extracts of leaf (Thomas et al., 2019), peel and seed from P. edulis demonstrate potential antioxidant and radical scavenging activities. P. edulis fruit showed a higher antioxidant activity (64% of DPPH reduced) than mango, pineapple, banana and litchi (45%–58%). In addition, passion fruit exerted a higher free radical-scavenging activity (14.08 μmol Trolox equivalent) than little banana, big banana, papaya Colombo, papaya solo, onion, nectarine, orange, mango american, pineapple, mango josé, and litchi (< 10 μmol Trolox equivalent). The variation of polyphenol components (286.6 mg gallic acid equivalent/100 g), total flavonoid (70.1 mg quercetin equivalent/100 g), carotenoid (3.8 mg β-carotene equivalent/100 g), vitamin C (44.4 mg ascorbic acid equivalent/100 g) may be responsible for the radical-scavenging activity (Septembre-Malaterre et al., 2016). Passion fruit seeds are rich in the total phenolic compounds, and show the highest antioxidant capacities in the FRAP assay (119.32 μmol FeSO4 g-1 DW) than pulp, raw peel, oven dried peel, lyophilized peel (27.16-60.27 μmol), while it showed antioxidant activity with the lowest IC50 value (DPPH) of 49.71 μmol than that of pulp (869.05 μmol), raw peel (347.56 μmol), oven dried peel (371.14 μmol), and lyophilized peel (225.29 μmol) (Morais et al., 2015). The in vivo treated the bark of P. edulis to obese male db/db mice could increase the antioxidant capacity of plasma, kidney, liver and adipose tissue, and reduce lipid oxidation of kidney and liver (Panelli et al., 2018). Furthermore, administration of P. edulis leaves, peel, and seeds to streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats showed antioxidant capacity by improving the anti-oxidants enzyme in animal visceral organs (da Silva et al., 2013; Kandandapani et al., 2015).

Analgesic and Anti-Inflammatory Activities

Analgesic Activity

Comparative studies showed that n-butanol extracts of P. edulis leaves had a dose-dependent analgesic activity in a thermal stimulation pain model (Nayak and Panda, 2012). In acetic acid-induced writhing, formalin-induced paw licking and response latency in the hot plate test, the polysaccharide of the dried fruit of the P. edulis reduced acetic acid induced writhing and formalin-induced paw licking, but it did not produced a significant increase in reaction time in the hot plate test, suggesting that the analgesic activity of polysaccharide is related to peripheral mechanisms (Silva et al., 2015). However, detailed and accurate data on the possible molecular mechanism and bioactive compounds are need to be carried out.

Anti-Inflammatory Activity

Anti-inflammatory activity of P. edulis extracts has been evaluated through in vivo tests like the inflammation induced by 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulphonic acid, dextran sodium sulphate carrageenan (Herawaty and Surjanto, 2017), substance P, histamine, bradykinin, and dextran sodium sulphate (Cazarin et al., 2016), and so forth. In a 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulphonic acid induced rat colitis model, the aqueous extract of P. edulis leaves reduced pro-inflammatory levels of IL-1β and TNF-α (Cazarin et al., 2015). In a dextran sodium sulphate caused mice colitis model, P. edulis peel flour reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-17 expression and decreased the expression of MCP-1 and ICAM-1 (Cazarin et al., 2016). This could be attributed to the presence of bioactive compounds like C-glycosyl flavonoids vicenin, orientin, isoorientin, vitexin and isovitexin. Intraperitoneal injection of the polysaccharide from the dried fruit of P. edulis at the dose of 3 mg/kg reduced mice paw oedema induced by the compound 48/80, carrageenan, histamine, serotonin, and prostaglandin E2, and significantly reduced vascular permeability, TNF-α and IL-1β level (Silva et al., 2015).

Antimicrobial Activity

The passion fruit possesses antifungal and antibacterial activity against fungi and bacteria which cause infectious diseases in human and plants. The peptide with close similarity to 2S albumins from passion fruit seeds has antifungal properties against Trichoderma harzianum, Fusarium oxysporum, Aspergillus fumigatus, Colletotrichum lindemuthianum, Kluyveromyces marxiannus, Candida albicans, Candida parapsilosis and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Agizzio et al., 2003; Pelegrini et al., 2006; Ribeiro et al., 2012; Jagessar et al., 2017). The methanol extracts of pericarp of P. edulis inhibited the growth of different bacterial strains such as Escherichia coli, Enterobacter aerogenes, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Providencia stuartii with minimum inhibitory concentrations ranging from 128 to 1024 μg/ml. This could be due to the presence of bioactive compounds such as polyphenols triterpenes, and sterols contained in the methanol extracts (Dzotam et al., 2016). Indeed, in a systematic study, Ramaiya et al. (2014) showed that the total phenolic and antioxidant contents had significantly antibacterial properties. Oil from yellow passion fruit seeds showed antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli, Salmonella enteritidis, Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus cereus. n-hexane, tocopherol, linoleic acid, unsaturated fatty acids were identified as major compounds in the oil (Pereira et al., 2019). However, in vivo and clinical studies are needed for confirmation.

Anti-Hypertensive Activity

The anti-hypertensive activity of both yellow and purple passion fruit products has been proved in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Oral administration of P. edulis peel extract reduced hemodynamic parameters, decreased serum nitric oxide level (Zibadia et al., 2007), and lowered blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats (Ichimura et al., 2006; Lewis et al., 2013). This could be attributed to the polyphenols such as luteolin, luteolin-6-C-glucoside, quercetin, edulilic acid, ascorbic acid, piceatannol (Kinoshita et al., 2013) and anthocyanin, and so forth. which can mediate nitric oxide modulation and have potent vascular effects (Ichimura et al., 2006; Lewis et al., 2013; Konta et al., 2014). However, the exact mechanisms and compounds responsible for this effect need further investigation.

Hepatoprotective and Lung-Protective Activities

Oral administration of purple passion fruit peel extract showed hepatoprotection against chloroform (1 mmol)-induced rat liver injury (Zibadia et al., 2007), and showed noteworthy hepatoprotective activity against CCl4 induced hepatotoxicity (Kavitha et al., 2016). In ethanol-induced liver injury, treated daily with fruit juices to mice for 15 days could protect ethanol-induced liver injury by decreasing AST and ALT in liver, and alleviating the inflammation, oxidative stress (Zhang et al., 2016). In addition, the passion fruit seed extract prevented non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by improving the liver hypertrophy and hepatic histology of the high-fat diet-fed rats (Ishihata et al., 2016). In a pulmonary fibrosis of C57BL/6J mice model induced by bleomycin, administration of passion fruit peel extract significantly reduced loss of body weight and mortality rate, decreased the count of inflammatory cells, macrophages, lymphocytes, and neutrophils, reduced MPO activity and restored bleomycin induced depletion of SOD activity.

Hypolipidemic Activity

Hyperlipidemia can directly cause some diseases that seriously endanger human health, such as atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, pancreatitis, and so forth. Passion fruit plays an important role in preventing hyperlipidemia. The passion fruit juice at a dose of 580 mg/kg once a day for 30 consecutive days significantly reduced total cholesterol, triglyceride, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, and increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level in diabetic Wistar rat offspring (Barbalho et al., 2011), and peel flour of P. edulis counteracted cumulative body weight gain, decreased adiposity and leptin level, increased adiponectin in diet-induced obesity in rat (Lima et al., 2016). Oral administration of pectin from P. edulis fruit peel 0.5–25 mg/kg for 5 days effectively decreased triglyceride levels in diabetic rats (Silva et al., 2011), and the insoluble fiber derived from seed of P. edulis decreased serum triglyceride and total cholesterol, liver cholesterol, and increased the cholesterol, total lipids, and bile acids levels in feces of golden Syrian hamsters (Chau and Huang, 2005).

Antidiabetic Activity

Diverse studies have demonstrated that peel flour, juice, and seeds of P. edulis showed antidiabetic potential effects by reducing glucose tolerance in diabetic mice, and rats. Oral administration of passion fruit juice at a dose of 580 mg/kg once a day for 30 consecutive days significantly reduced glucose in streptozotocin induced diabetic rat offspring (Barbalho et al., 2011), and administration of passion fruit seed or leaf extract also reduced the blood glucose levels of db/db mice, alloxan induced diabetes mellitus in Wistar albino rats or streptozotocin (STZ) induced diabetic rats (Kanakasabapathi and Gopalakrishnan, 2015; Panchanathan and Rajendran, 2015; Uchida-Maruki et al., 2015). Oral administration of pectin from P. edulis fruit peel at a dose of 0.5–25 mg/kg daily for 5 days lowered blood glucose in diabetic rats induced by alloxan, providing a new treatment for type 2 diabetes (Silva et al., 2011). Peel flour of P. edulis intake increased glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon-like peptide-1, improved the insulin sensitivity in high-fat diet-induced obesity rats by increasing the glucose disappearance rate (Lima et al., 2016), and also prevents insulin resistance induced by low-fructose-diet in rats. In addition, the leaf extract of P. edulis full of flavonoids also has a health benefit to the diabetic state, and show the prevent effect on the appearance of its complications (Salles et al., 2020; Soares et al., 2020).

Antidepressant Activity

Antidepressant potential of stems and leaves extracts has been certified in vivo. Oral administration of ethanol extracts of the aerial parts (equal to 10 and 2 g/kg of the plant materials) of P. edulis to mice for 7 day exhibited antidepressant-like effect via reduced immobility time in the forced swim and tail suspension tests in mice. Further evidence showed that the cycloartane triterpenoid cyclopassiflosides IX and XI at the dosage of 50 mg/kg possessed an antidepressant-like effect, which indicated that those cycloartane triterpenoids may be the main responsible bioactive compounds of P. edulis (Wang et al., 2013). Oral administration of the aqueous (300 mg/kg), ethyl acetate (50 mg/kg), and butanol extracts (50 mg/kg) of P. edulis Sims fo edulis reduced the immobility time in the mice forced swimming test, which is similar to nortriptyline and fluoxetine. Particularly, ethyl acetate and butanol extract rich in flavonoids showed preferably the antidepressant effects, and that can be counteracted by p-chlorophenylalanine, α-methyl-DL-tyrosine chloride and sulpiride, suggesting this action is related exclusively to regulate serotonergic and dopaminergic transmission such as 5-HT, catecholamine and D2 receptor (Ayres et al., 2017).

Anxiolytic-Like Activity

The fragrant fruits and their twigs and leaf of P. edulis Sims are most used as a folk medicine in treating anxiety in American countries. In vivo data suggest that varieties of crude extracts like butanolic, methanol, ethanol, hydro-ethanol, and aqueous extract showed anxiolytic-like effect in the model tested. The aqueous extract of P. edulis at 50, 100, and 150 mg/kg showed anxiolytic-like effects in the elevated plus-maze and inhibitory avoidance tests in rat. More importantly, administration of the aqueous extract of P. edulis did not disrupted rat memory process in an habituation to an open-field test, but diazepam impaired rat habituation with a simple modification of the open-field apparatus (Barbosa et al., 2008).

The methanol extract of aerial parts of P. edulis Sims at an oral dose of 75 mg/kg showed anxiolytic activity on the elevated plus-maze model of anxiety in mice, but oral dose of 125 mg/kg did not evoke any significant activity. Whereas, oral at higher doses of 200 and 300 mg/kg showed a mild sedative effect (Dhawan et al., 2001). Pre-treatment with 50, 100, and 150 mg/kg hydroethanol extracts and 400 and 800 mg/kg of spray-dried powders of P. edulis leaves also showed anxiolytic activity in the elevated plus-maze test in mice. It was suggested that the therapeutic effect of these extracts was due to the presence of a wide range of flavonoids such as isoorientin, orientin, luteolin, apigenin, and chrysin or their glycosides, and so forth (Petry et al., 2001; Coleta et al., 2006; Otify et al., 2015).

Sedative Activity

There is cumulative evidence to suggest that P. edulis possess sedative activity, which are certified its therapeutic applications in insomnia in traditional folk medicines. Oral administration of aqueous extracts of pericarp and the leaves (300 mg/kg, 600 mg/kg and 1,200 mg/kg) of P. edulis f. flavicarpa Degener showed a rapid onset of action and a significant decrease dose-dependently in locomotor activity in C57BL/6J mice using radiotelemetry. It is noteworthy to mention that aqueous extracts of pericarp showed more significant effects on locomotor activity while compared to leaves extracts (Klein et al., 2014). 300 mg/kg n-BuOH and ethanolic extract of aerial part of P. edulis f. flavicarpa Degener hindered motor activity of mice, showing a sedative-like effect. Flavonoids, especially, isoorientin were identified as a major sedative constituent in the extract (Deng et al., 2010). The aqueous extracts mainly contain C-glycosylflavonoids isoorientin, vicenin-2, spinosin, and 6,8-di-C-glycosylchrysin. In addition, ethanolic extract is composed of flavonoids like isovetexin, apigenin-6-C-β-D-glucopyrano-4′-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside, luteolin 6-C-β-D-chinovoside, and luteolin 6-C-β-D-fucoside (Zhou et al., 2009). Thus, the flavonoids may be responsible for the sedative activity of P. edulis f. flavicarpa Degener.

Antitumor Activity

Most of the pharmacological work has been carried out on the antitumor activity of P. edulis. In vitro, the different varieties of extracts of P. edulis showed cytotoxicity against HepG2 (Aguillón et al., 2018), MCF-7, SW480, SW620, Caco-2 (Ramirez et al., 2017; Sandra et al., 2017; Mota et al., 2018), CCRF-CEM, CEM/ADR5000, and HCT116 [p53(-/-)] (Kuete et al., 2016). It was found that higher content of polyphenolic and polysaccharide contained in ethanolic extract may be related to the inhibition of matrix-metalloprotease MMP-2 and MMP-9 (Puricelli et al., 2003). In vivo, the ethanol extract of yellow passion fruit inhibited tumor growth with an inhibition rate of 48.5% and increased mice lifespan to nearly 42% in male Balb/c mice inoculated with Ehrlich carcinoma cells. This could be attributed to the presence of medium and long chain fatty acids such as lauric acid (Mota et al., 2018). Oral or intraperitoneal administration of the polysaccharide showed the inhibition of the growth of sarcoma 180 tumors with an inhibition ratio ranging from 40.59% to 48.73% (Silva et al., 2012).

Clinical Effectiveness in Humans

Although the use of P. edulis has a key role in management of various ailments in folk medicine and in various preclinical experiments, the efficacy of this plants has not been explored in depth in human clinical trials. So far, few clinical trials of P. edulis have been conducted to determine if improved chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and asthma. An open, prospective, randomized clinical trial studies showed that combined use of the yellow passion fruit peel flour and hypoglycemic drugs like glyburide, metformin, and insulin, and so forth. exerted a favorable effect on insulin sensitivity during the 60 days period in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients (de Queiroz Mdo et al., 2012), but the single use of flour made from the rind of the yellow passion fruit over 56 days did not significantly improve glycemic control on type 2 diabetes patients (de Araújo et al., 2017). This seems to be inconsistent with the results of animal experiments, so it remains to verify the antiglycation effect using a multitude of reliable experimental probes and to explicit which type of chemical composition is mostly responsible for promoting the activity of hypoglycemic agents. In 28 days randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial, orally administered of purple passion fruit peel extract at 400 mg/day significantly decreased systolic and diastolic blood pressure by 30.9 and 24.6 mmHg, respectively (Zibadia et al., 2007). Oral administration of purple passion fruit peel 150 mg/day in 28 days clinical trial can effectively alleviate the clinical symptoms of cough by reducing wheeze and cough and improving shortness of breath in adults with asthma, and no adverse effects were found in this study (Watson et al., 2008). Meanwhile, oral administration of purple passion fruit peel 150 mg/day for 56 days in clinical trial substantially alleviated osteoarthritis symptoms, and its beneficial effects may be due to the anti-inflammatory properties (Farid et al., 2010). In general, these interesting studies may contribute to a better understanding of clinical efficacy of P. edulis. However, in consideration of the significant in-vitro and in vivo pharmacological activities of P. edulis, more randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled and cross‐over studies are urgently needed.

Toxicity

Many researches show that passion fruit does not cause any harmful side effects. In vivo acute and subacute toxicity studies indicate that oral administration of the ethanol extract of unripen fruit peel of P. edulis at the dose of 550 mg/kg had no toxic effect on the rats. Administration of the aqueous extract of P. edulis leaf was found to be safe even at the dose of 2,000 mg/kg. Importantly, mice behavioral pattern and hematologic parameters including RBC, Hb, WBC, MCV, MCH, platelets, neutrophils and lymphocytes had no abnormal change (Anurangi and Shamina, 2018). The subacute study showed that the aqueous extract was safe on the bone marrow function and it was neither hepatotoxic nor nephrotoxic (Devaki et al., 2012). These results provide a basis to further explore the clinical uses of passion fruit. However, more and extensively studies are still needed on its bioavailability and toxicity in animals and humans.

Processing and Applications

Usually, passion fruit with an intense aroma can be eaten directly. Passion fruit is liable to deteriorate and has a short shelf life. Packaging with high oxygen (90%) atmosphere can effectively inhibit respiration and peel shape, keep vitamin C and solubility solids content, and increase total phenols content in passion fruit, improving the postharvest quality of passion fruit (Chen et al., 2018). Different processing methods affected the composition and activity of passion fruit. Steaming and boiling compared to frying protect the health-promoting properties of passion fruit (Gunathilake et al., 2018b). Today, passion fruit has been processed into a range of products on the basis of the attractive health effects and full of phytonutrients. A wide range of products made with passion fruit has been developed including cake, ice cream, jam, jelly, yoghurt, compound beverage, tea, wine, vinegar, soup-stock, condiment sauce, and so on. Additionally, many kinds of passion fruit drink with a refreshing taste are being prepared combining with Chinese medicines including Lycium barbarum and Dendranthema morifolium, and so forth, and are suitable for people to drink in the light of the vitamin supplementation, strengthening immunity, nourishing skin, and resisting fatigue (Zhang, 2018). Seed oil of P. edulis may be developed as functional food such as tea cream with whitening and anti-wrinkle effects. The nutritional ingredients and biological properties of P. edulis provide a strong basis for the development of P. edulis based food products.

The pulp of passion fruit can be both eaten or commonly juiced. The juice is often added to other juices to enhance its aroma. The passion fruit peel accounts for about 51% the fruit wet weight. Because of the large amount of fruit juice production, many thousand tons of seeds, pulps, and peels as agricultural coproducts during juice extraction. Peels, as the major wastes, have become an important burden on the environment. With the development of economy and people’s awareness of environmental protection, peel has been used extensively in the industrial production of pectin. It is a widely used functional food raw material with high value in reducing cholesterol levels, reducing hyperlipidemia, and hypertension, improving glucose tolerance and insulin response, helpful to gastrointestinal health and the prevention of some cancers. Pectin is used as a nutritional fiber delivery, gelling agent, and edible coating and stabilizer in the pharmaceutical, cosmetic and food industry, especially in the production of confectionery, jelly, and other products (de Souza et al., 2018). Pectin-based edible coating plays a waterproof role in fruit preservation, which have the functions of preventing moisture transfer and flavor loss, and improving hardness. The production of commercial pectin from passion fruit peel, seeds and bagasse could not only eliminate the problem of waste, but also provide a new source for pectin industry.

Conclusions and Future Research Directions

Passion fruit is most popular for its attractive nutritional and sensory qualities to the health and well beings of the worldwide consumer. Secondary metabolites in passion fruit have been attracting considerable attention because these compounds exert numerous health benefits and economic value, and thus have been used in nutrition, cosmetics and medicine. Passion fruit and its by-products full of various chemical constituents and phytonutrients including polyphenols, dietary fiber, pectin, carotenes, and vitamin. The chemical constituents and properties of different kinds of passion fruit are diverse. Yellow passion fruit presented higher water and relatively lower nutritional components, while purple fruit presented higher content of vitamin C, vitamin A, fiber and calcium. Different plant parts (leaves, buds, peels, and pulp) and growth stages of P. edulis contain a variety of bioactive components such as total dietary and polyphenols. The yellow passion fruit presented higher content of pectin in peels, high content of carotene, quercetin, and kaempferol in pulps and higher values of total dietary fiber in seeds. The purple fruit was highlighted by a great value of anthocyanins in peels and seeds. Passion fruit peels as food waste account for 50% of the total fruit has also a high potential to obtain functional ingredients because it rich in biological active ingredients. Because of the unique bioactive constituents in passion fruit, diverse nutritional and medical benefits have been watched and recorded. The various extracts from different parts of P. edulis exhibited numerous pharmacological activities including antioxidant, analgesic and anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anti-hypertensive, hepatoprotective and lung-protective, anti-tumor, antidiabetic, hypolipidemic, antidepressant and anxiolytic-like capacities, and thus are used in phytotherapeutic remedies. In particular, acute toxicity and subacute toxicity studies have shown that a rationalized daily dose of passion fruit is probably safe for consumption. These outstanding results suggest that passion fruit may offer a range of health benefits, such as managing inflammatory and neurological disease, and also preventing some chronic diseases like hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

There are also research opportunities to better utilize passion fruit and its by-products for human consumption. Both passion fruit and its by-products are a rich source of polyphenols, so it is very important to optimization of appropriate processing methods to stabilize and improve the quality of these processed product. The structure and characteristics of polysaccharides in fruits remains to be studied. Pesticides may be present on the fruit and should be strictly monitored and controlled. Influence of genetic diversity, processing approach and living environment on chemical composition and nutritional value of passion fruit should be further explored. Studies on varieties of P. edulis are very limited, especially the confusion between P. edulis and P. incarnata remains, that need to be attracted special attention from botanist. The pharmacological activity reports of the P. edulis plant are mostly based on preliminary evaluation, and the models used lack appropriate standards or reasonable dosage. P. edulis has showed therapeutic potentials as in vitro anticancer agent against various tumor cell lines, but in vitro cytotoxic activities need to be supported with the in vivo studies and clinical trials to confirm its role as an anticancer agent in future. The structure-activity relationship and molecular mechanism of bioactive compounds or crude extracts of P. edulis will also be the focus of future research and practice. More importantly, clinical trial on P. edulis efficacy and safety are very scarce to support claims of efficacy.

Author Contributions

YY, MW, MZ and JF obtained the literatures. FL, ZZ, and XH wrote the manuscript. XH, YL, and ZW gave ideas and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the paper for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Research Foundation in Scientific and Technological Activities for the Overseas Chinese Scholars, Guizhou Province (2018)0013.

Abbreviations

5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; AAPH, 2,20-azobis[2-methyl-propionamidin] dihydrochloride; ABTS, 2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid); ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BP, blood pressure; Caco-2, human cloned colon adenocarcinoma cells Caco-2; CCl4, carbon tetrachloride;COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; DMH, 1,2-di-Me hydrazine; DPPH, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; FRAP, ferric ion reducing antioxidant power; GC-MS, gas chromatography-mass spectrometer; GC-O, gas chromatography-olfactometry; Hb, hemoglobin; HOCI, hypochlorite; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; HR, heart rate; HRGC-MS, high resolution gas chromatography-mass spectrometry; ICAM-1, intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1; IL-12, interleukin-12; IL-17, interleukin-17; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-6, interleukin-6; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; Ki67, antigen KI-67; LC-DAD-ESI-MS, liquid chromatography-diode array detector-electrospray ionization/mass spectrometric; MCF-7, human breast adenocarcinoma cell line; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCP-1, human monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MCV, erythrocyte mean corpuscular volume; MMP-2, matrix metallopeptidase 2; MMP-9, matrix metallopeptidase 9; MPO, myeloperoxidase; NO, nitric oxide; NGF, nerve growth factor; ORAC, oxygen radical absorbance capacity; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; RBC, red blood cell; SOD, superoxide dismutase; STZ, streptozotocin; SW480, human colon cancer cell line SW480; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; UHPLC-MS/MS, ultraperformance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry; WBC, white blood cell.

References

- Agizzio A. P., Carvalho A. O., Ribeiro S. F., Machado O. L., Alves E. W., Okorokov L. A., et al. (2003). A 2S albumin-homologous protein from passion fruit seeds inhibits the fungal growth and acidification of the medium by Fusarium oxysporum. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 416, 188–195. 10.1016/S0003-9861(03)00313-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguillón J., Arango S. S., Uribe D. F., Loango N. (2018). Citotoxyc and apoptotic activity of extracts from leaves and juice of passiflora edulis. J. Liver Res. Disord. Terapy J. Liver Res. Disord. Ther. 4, 67–71. 10.15406/jlrdt.2018.04.00102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anurangi C. R., Shamina S. (2018). Preliminary phytochemical screening and acute & subacutetoxicity study on different concentrations of unripen fruit peel flour of Passiflora edulis in male albino rats. World J. Pharm. Pharmaceut. Sci. 7, 828–834. 10.20959/wjpps20183-11113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arai D., Kataoka R., Otsuka S., Kawamura M., Maruki-Uchida H., Sai M., et al. (2016). Piceatannol is superior to resveratrol in promoting neural stem cell differentiation into astrocytes. Food Funct. 7, 4432–4441. 10.1039/C6FO00685J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo C. L., Bezerra I. W. L., Dantas I. C., Lima T. V. S., Oliveira A. S., Miranda M. R. A., et al. (2003). Biological activity of proteins from pulps of tropical fruits. Food Chem. 85, 107–110. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2003.06.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga A. M. C., Craveiro A. A., Machado M. I. L., Pouliquen Y. B. M. (1997). Volatile constituents from fruit shells of Passiflora edulis Sims. J. Essent. Oil Res. 9, 235–236. 10.1080/10412905.1997.9699469 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayres A. S. F. S. J., Santos W. B., Junqueira-Ayres D. D., Costa G. M., Ramos F. A., Castellanos L., et al. (2017). Monoaminergic neurotransmission is mediating the antidepressant-like effects of Passiflora edulis Sims fo. Edulis. Neurosci. Lett. 660, 79–85. 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbalho S. M., Damasceno D. C., Spada A. P., Lima I. E., Araújo A. C., Guiguer E. L., et al. (2011). Effects of Passiflora edulis on the metabolic profile of diabetic Wistar rat offspring. J. Med. Food 14, 1490–1495. 10.1089/jmf.2010.0318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa P. R., Valvassori S. S., Bordignon C. L., Jr., Kappel V. D., Martins M. (2008). The aqueous extracts of Passiflora alata and Passiflora edulis reduce anxiety-related behaviors without affecting memory process in rat. J. Med. Food 11, 282–288. 10.1089/jmf.2007.722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombardelli E., Bonati A., Gabetta B., Martinelli E. M., Mustich G. (1975). Passiflorine, a new glycoside from Passiflora edulis. Phytochemistry 14, 2661–2665. 10.1016/0031-9422(75)85246-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cazarin C. B. B., Silva J. K., Colomeu T. C., Batista Â.G., Meletti L. M. M., Paschoal J. A. R., et al. (2015). Intake of Passiflora edulis leaf extract improves antioxidant and anti-inflammatory status in rats with 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulphonic acid induced colitis. J. Funct. Foods 17, 575–586. 10.1016/j.jff.2015.05.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cazarin C. B. B., Rodriguez-Nogales A., Algieri F. M., Utrilla P., Rodríguez-Cabezas M., Garrido-Mesa J., et al. (2016). Intestinal anti-inflammatory effects of Passiflora edulis peel in the dextran sodium sulphate model of mouse colitis. J. Funct. Foods 26, 565–576. 10.1016/j.jff.2016.08.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y. W., Su J. D. (1998). Antioxidant activity of major anthocyanins from skins of passion fruit. Shipin Kexue (Taipei) 25, 651–656. [Google Scholar]

- Chassagne D., Crouzet J. (1998). A cyanogenic glycoside from Passiflora edulis fruits. Phytochemistry 49, 757–759. 10.1016/S0031-9422(98)00130-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chassagne D., Bayonove C. L., Brillouet J.-M., Baumes R. L. (1996). 6-O-α-L-Arabinopyranosyl-β-D-glucopyranosides as aroma precursors from passion fruit. Phytochemistry 41, 1497–1500. 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00814-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassagne D., Crouzet J., Bayonove C. L., Baumes R. L. (1997). Glycosidically bound eugenol and methyl salicylate in the fruit of edible Passiflora species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 45, 2685–2689. 10.1021/jf9608480 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chau C. F., Huang Y. L. (2003). Characterization of passion fruit seed fibres-a potential fibre source. Food Chem. 85, 189–194. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2003.05.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chau C. F., Huang Y. L. (2005). Effects of the insoluble fiber derived from Passiflora edulis seed on plasma and hepatic lipids and fecal output. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 49, 786–790. 10.1002/mnfr.200500060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F. P., Xu X. Y., Luo Z., Chen Y. L., Xu Y. J., Xiao G. S. (2018). Effect of high O2 atmosphere packaging on postharvest quality of purple passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims). J. Food Process. Preserv. 42 (9), e13749.1–e13749.7. 10.1111/jfpp.13749 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J., Jaroszewski J. W. (2001). Natural glycosides containing allopyranose from the passion fruit plant and circular dichroism of benzaldehyde cyanohydrin glycosides. Org. Lett. 3, 2193–2195. 10.1021/ol016044+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuyen H. V., Eun J. B. (2017). Marine carotenoids: Bioactivities and potential benefits to human health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 57, 2600–2610. 10.1080/10408398.2015.1063477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleta M., Batista M. T., Campos M. G., Carvalho R., Cotrim M. D., de Lima T. C. M., et al. (2006). Neuropharmacological evaluation of the putative anxiolytic effects of Passiflora edulis Sims, its sub-fractions and flavonoid constituents. Phytother. Res. 20, 1067–1073. 10.1002/ptr.1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa R. C. G., Peralta R. M., Haminiuk C. W. I., Maciel G. M., Bracht A., Ferreira I. C. F. R. (2016). The past decade findings related with nutritional composition, bioactive molecules and biotechnological applications of Passiflora spp. (Passion Fruit) Trends Food Sci. Technol. 58, 79–95. 10.1016/j.tifs.2016.10.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva J. K., Cazarin C. B. B., Colomeu T. C., Batista Â.G., Meletti L. M. M., Paschoal J. A. R., et al. (2013). Antioxidant activity of aqueous extract of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) leaves: In vitro and in vivo study. Food Res. Int. 53, 882–890. 10.1016/j.foodres.2012.12.043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Araújo M. F. M., Veras V. S., de Freitas R. W. J. F., de Paula M. D. L., de Araújo T. M., Uchôa L. R. A., et al. (2017). The effect of flour from the rind of the yellow passion fruit on glycemic control of people with diabetes mellitus type 2: a randomized clinical trial. J. Diab. Metabol. Disord. 16, 18. 10.1186/s40200-017-0300-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Queiroz Mdo S., Janebro D. I., da Cunha M. A., Medeiros Jdos S., Sabaa-Srur A. U., Diniz Mde F., et al. (2012). Effect of the yellow passion fruit peel flour (Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa deg.) in insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Nutr. J. 11, 89. 10.1186/1475-2891-11-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Santana F. C., de Oliveira T. L. R., Shinagawa F. B., de Oliveira E. S. A. M., Yoshime L. T., de Melo I. L. P., et al. (2017). Optimization of the antioxidant polyphenolic compounds extraction of yellow passion fruit seeds (Passiflora edulis Sims) by response surface methodology. J. Food Sci. Technol. 54, 3552–3561. 10.1007/s13197-017-2813-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza C. G., Rodrigues T. H. S., Silva L. M. A., Ribeiro P. R. V., de Brito E. S. (2018). Sequential extraction of flavonoids and pectin from yellow passion fruit rind using pressurized solvent or ultrasound. J. Sci. Food Agric. 98, 1362–1368. 10.1002/jsfa.8601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J., Zhou Y., Bai M., Li H., Li L. (2010). Anxiolytic and sedative activities of Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 128, 148–153. 10.1016/j.jep.2009.12.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaki K., Beulah U., Akila G., Gopalakrishnan V. K. (2012). Effect of aqueous extract of Passiflora edulis on biochemical and hematological parameters of Wistar albino rats. Toxic. Int. 19, 63–67. 10.4103/0971-6580.94508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan K., Kumar S., Sharma A. (2001). Comparative biological activity study on Passiflora incarnata and P. Edulis. Fitoter. 72, 698–702. 10.1016/S0367-326X(01)00306-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan K., Dhawan S., Sharma A. (2004). Passiflora: a review update. J. Ethnopharmacol. 94, 1–23. 10.1016/j.jep.2004.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Reis L. C. R., Facco E. M. P., Salvador M., Flôres S. H., de Oliveira Rios A. (2018). Antioxidant potential and physicochemical characterization of yellow, purple and orange passion fruit. J. Food Sci. Technol. 55, 2679–2691. 10.1007/s13197-018-3190-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzotam J. K., Touani F. K., Kuete V. (2016). Antibacterial and antibiotic-modifying activities of three food plants (Xanthosoma mafaffa Lam., Moringa oleifera (L.) Schott and Passiflora edulis Sims) against multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacteria. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 16, 1–8. 10.1186/s12906-016-0990-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel K. H., Tressl R. (1991). Identification of new sulfur-containing volatiles in yellow passionfruit (Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa). J. Agric. Food Chem. 39, 2249–2252. 10.1021/jf00012a030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farid R., Rezaieyazdi Z., Mirfeizi Z., Hatef M. R., Mirheidari M., Mansouri H., et al. (2010). Oral intake of purple passion fruit peel extract reduces pain and stiffness and improves physical function in adult patients with knee osteoarthritis. Nutr. Res. 30, 601–606. 10.1016/j.nutres.2010.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas M. S. M., Monnerat P. H., Vieira I. J. C., Carvalho A. J. C. (2007). Flavonoids and mineral composition of leaf in yellow passion fruit plant as function of leaves positions in the branch. Cienc. Rural 37, 1634–1639. 10.1590/S0103-84782007000600020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goss M. J., Nunes M. L. O., Machado I. D., Merlin L., Macedo N. B., Silva A. M. O., et al. (2018). Peel flour of Passiflora edulis Var. Flavicarpa supplementation prevents the insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis induced by low-fructose-diet in young rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 102, 848–854. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.03.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunathilake K. D. P. P., Ranaweera K. K. D. S., Rupasinghe H. P. V. (2018. a). Analysis of rutin, β-carotene, and lutein content and evaluation of antioxidant activities of six edible leaves on free radicals and reactive oxygen species. J. Food Biochem. 42, e12579–. 10.1111/jfbc.12579 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunathilake K. D. P. P., Ranaweera K. K. D. S., Rupasinghe H. P. V. (2018. b). Influence of boiling, steaming and frying of selected leafy vegetables on the in vitro anti-inflammation associated biological activities. Plants (Basel) 7, 22. 10.3390/plants7010022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M. J., Zeng J. Y., Zhai L., Liu Y. G., Wu H. C., Zhang R. F., et al. (2017). Effect of in vitro simulated gastrointestinal digestion on polyphenol and polysaccharide content and their biological activities among 22 fruit juices. Food Res. Int. 102, 156–162. 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herawaty G., Surjanto R. ,. J. (2017). Antiinflammatory effects of ethanolic extract of purple passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims.) peel against inflammation on white male rats foot. Int. J. Chem. Tech. Res. 10, 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- Herderich M., Winterhalter P. (1991). 3-Hydroxy-retro-α-ionol: a natural precursor of isomeric edulans in purple passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims). J. Agric. Food Chem. 39, 1270–1274. 10.1021/jf00007a015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Jiao L., Jiang M. H., Yin S., Dong P., Zhao Z. M., et al. (2018). A new C-glycosyl flavone and a new neolignan glycoside from Passiflora edulis Sims peel. Nat. Prod. Res. 32, 2312–2318. 10.1080/14786419.2017.1410809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura T., Yamanaka A., Ichiba T., Toyokawa T., Kamada Y., Tamamura T., et al. (2006). Antihypertensive effect of an extract of Passiflora edulis rind in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Biosci. Biotech. Bioch. 70, 718–721. 10.1271/bbb.70.718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihata A., Maruki-Uchida H., Gotoh N., Kanno S., Aso Y., Togashi S., et al. (2016). Vascular- and hepato-protective effects of passion fruit seed extract containing piceatannol in chronic high-fat diet-fed rats. Food Funct. 7, 4075–4081. 10.1039/c6fo01067a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagessar R. C., Hafeez A., Chichester M., Crepaul Y. (2017). Antimicrobial activity of the ethanolic and aqueous extract of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims), in the absence and presence of Zn (OAc)2.-H2O. World J. Pharm. Pharmaceut. Sci. 6, 230–246. 10.20959/wjpps20179-10010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]