Abstract

Maternal education represents one of the most important social determinants of inequality in birth weight (BW) in developing countries. The present study sought to investigate secular trends in health inequality considering the difference in mean BW between extremes of maternal educational attainment in Brazil. Using a time-series design, data from 6,452,551 live births which occurred in all Brazilian state capitals from 1996 to 2013 were obtained from the Information System on Live Births. Secular trends of the difference in mean birth weight between low (<8 years of schooling) and high (≥12 years of schooling) educational attainment were analyzed. The main finding was that differences in mean birth weight between the two extremes of maternal educational attainment decreased over time. There was a significant decrease in mean BW in neonates born to mothers with higher educational attainment, and a slight increase in those born to mothers with lower educational attainment. One of the key factors involved in decreasing inequality was an increase in the number of antenatal visits. In view of these results, we conclude, that despite a slight increase of mean birth weight among mothers with low education, the reduction of inequality in pregnancy outcomes over time in Brazil is attributable to a worsening scenario for mothers who are better off rather than to improvements for the most vulnerable group of mothers.

Subject terms: Neonatology, Epidemiology, Risk factors

Introduction

Socioeconomic status is considered an important predictor of health inequalities. Individuals in unfavorable socioeconomic conditions are more vulnerable to adverse physical and mental health outcomes compared to those who are better off1.

Several demographic and socioeconomic conditions influence birth outcomes. Among them, ethnicity, education, occupation, income, social class, the availability of housing, urban infrastructure, social support, and exposure to crime have all been described2.

The impact of social inequalities on human health is well established, and has shown increasing relevance in developing countries. Thus, in these countries, it is important to encourage social and economic development policies which, together with public health programs, may favorably influence perinatal outcomes, particularly birth weight3,4. At the individual level, access to health care, medical practices, behavioral factors, and stress are also related to birth weight5,6.

Maternal education is a strong determinant of birth weight acting through a number of mediators such as adequate access to information, health care and nutrition7. In Brazil, we have shown in a previous study, despite significant improvements in maternal education, the rate of LBW remained stable around 8.5% of all life births during the last 15 years8. In Brazil, this situation regarding LBW is considered an epidemiological paradox and, according to some researchers, it can be explained by several factors, among them, the underreporting in the registry of low birth weight in the poorest and most vulnerable regions and, at the same time, the intense use of health care technologies such as cesarean sections and assisted reproduction techniques in other wealthier regions with more favorable socioeconomic conditions in the country9.

Birth weight has impacts that persist throughout the life cycle, and its determinants are many6,10. Biological, demographic, socioeconomic, and environmental factors during pregnancy have a significant influence on birth weight10–14. Among these, maternal social integration is considered one of the most relevant. Mothers exposed to stress are more likely to engage in high-risk behaviors such as smoking, alcohol intake, and psychoactive drug use, and are more likely to be overweight or obese—all factors which have been associated with lower birth weight15. Maternal education is also among the most relevant social determinants of child health; mothers with low educational attainment are at higher risk of delivering low birthweight infants7,8,16,17.

Average birth weight has increased in many countries over the last three decades, due to improved access to antenatal care and population-wide improvements in socioeconomic condition4,18. However, some recent studies have found that mean birth weight has declined in some developed countries, although specific causes have not been identified10,19. Therefore, mean birth weight has presented different secular trends among different countries, under the influence of several determinants.

Brazil has one of the highest rates of low birth weight among developing countries, at approximately 8,0% and remaining stable over the last 10 years8,20. This rate is strongly influenced by sociodemographic factors and by access to adequate health care, and thus reflects high inequality among the different social classes and geographic regions of the country. However, the assessment of rates of low birth weight alone is not able to show the small impacts of the various individual social determinants of birth weight over time9,21.

Therefore, the objective of this study is to evaluate the influence of inequality between extremes of maternal education on birth weight, considering the trend of absolute and relative differences in mean birth weight over time among mothers with higher and lower educational attainment in an 18-year time series (1996–2013) in Brazil.

Methods

Data source and study population

This time-series study included all live births which occurred in 26 Brazilian state capitals and the Federal District from 1996 to 2013. Data were obtained from the Information System on Live Births (Sistema de Informação sobre Nascidos Vivos, SINASC), which covers 96% of all live births in Brazil22. This open-access database is available through the Ministry of Health website (http://datasus.saude.gov.br) or directly on the Health Information page of the Unified Health System Department of Informatics – DATASUS (http://datasus.saude.gov.br/informacoes-de-saude/tabnet).

Multiple births were excluded, as were newborns weighing <500 g or >8,000 g. These exclusions represented 6.02% of all live births during the period of interest (Table 1). The decision to use only information about births occurring in Brazilian capitals was based on the recognition that, in these cities, epidemiological surveillance services are more consolidated and have a more robust structure, which ensure greater completeness and reliability of data23.

Table 1.

Number of exclusions according to the pre-established criteria.

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Multiple deliveries | 253,937 (1.98) |

| Missing Information on birth weight | 52,461 (0.40) |

| Births outside state capitals | 486,754 (3.64) |

| Total | 793,152 (6.02) |

Overall, there were 6,452,551 live births in Brazilian state capitals and the Federal district during the study period, representing 11.92% of all live births in the country. Assessment for completeness showed a missing data rate <0.5%22,23.

Outcome, variable, and covariables of interest

Trends in mean birth weight (in grams) over time, presented as a continuous variable, were the outcome of interest. The investigated variable, maternal educational attainment, was dichotomized into two extremes: low and high (<8 and ≥12 years of formal schooling, respectively). Thus, extreme levels of maternal education were used because we understand that these categories are more subject to the potential impact of access to health services and technologies during antenatal and perinatal care on birth weight24.

The following covariables were considered: maternal age (10–17, 18–34, ≥35 years), number of previous live births (0 or ≥1), number of antenatal visits (none, <6, or ≥7 visits), gestational age (˂37 or ≥37 weeks), and mode of delivery (vaginal or cesarean). State capitals were grouped by the five geographic regions of Brazil25.

Statistical analysis

Birth weight means were calculated yearly for each Brazilian capital. The absolute and relative differences in mean birth weight between the two extremes of maternal education were calculated to assess the inequality between them.

The annual means of birth weight differences between the two extremes of maternal education was estimated using a linear mixed model26 for the years 1996 to 2003 and 2004 to 2013. We split in two periods of time after analysis using Joinpoint Regression Program Software Environment (version 4.3.1). The variables year and geographical region of birth were entered into the initial (standard) model (Model a). The covariables maternal age (Model b), number of children (Model c), number of antenatal visits (Model d), gestational age (Model e), and mode of delivery (Model f) were sequentially included.

Statistical analysis was performed in PASW Statistics, Version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), with a 5% significance level and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Ethical aspects

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (Brazil) with opinion number 16–0338. The study was carried out in accordance with national and international guidelines.

Results

During the study period, there was a significant reduction in adolescent pregnancies. There was also an increase in cesarean sections among mothers with low educational attainment, which, by the end of the period, was equivalent to approximately half of the percentage observed among mothers with high educational attainment. The descriptive variables used in the study, including maternal socioeconomic conditions, number of previous live births, number of antenatal visits, percentage of pregnancies in adolescence, cesarean sections, and preterm deliveries, are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Percent distribution of descriptive variables (maternal socioeconomic conditions: number of previous live births, number of prenatal visits, teenage pregnancy, cesarean section, preterm newborns) in Brazilian state capitals, 1996–2013.

| Year of birth | Maternal education | Number of primiparous mothers (%) | <6 antenatal visits (%) | Cesarean section (%) | Preterm birth (<37w) (%) | Teenage pregnancy (10–17 y.o.) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | <8 years | * | 57.8 | 28.0 | 5.6 | 10.1 |

| ≥12 years | * | 9.8 | 78.6 | 4.7 | ||

| 1997 | <8 years | 25.6 | 58.6 | 29.4 | 5.2 | 10.4 |

| ≥12 years | 40.5 | 9.2 | 78.2 | 4.9 | ||

| 1998 | <8 years | 29.3 | 61.9 | 28.1 | 6.8 | 10.3 |

| ≥12 years | 48.5 | 7.4 | 78.9 | 5.0 | ||

| 1999 | <8 years | 30.3 | 61.1 | 29.9 | 6.1 | 10.0 |

| ≥12 years | 46.5 | 19.7 | 68.2 | 5.3 | ||

| 2000 | <8 years | 28.2 | 58.5 | 29.6 | 6.0 | 9.8 |

| ≥12 years | 46.5 | 20.3 | 67.0 | 6.1 | ||

| 2001 | <8 years | 27.2 | 58.0 | 29.9 | 6.6 | 9.6 |

| ≥12 years | 47.2 | 18.0 | 68.5 | 6.0 | ||

| 2002 | <8 years | 24.3 | 56.8 | 29.7 | 6.7 | 9.4 |

| ≥12 years | 44.3 | 17.1 | 69.2 | 6.4 | ||

| 2003 | <8 years | 25.6 | 55.6 | 30.5 | 6.9 | 9.2 |

| ≥12 years | 48.1 | 15.1 | 70.8 | 6.9 | ||

| 2004 | <8 years | 26.4 | 55.3 | 32.3 | 6.9 | 8.8 |

| ≥12 years | 50.3 | 15.5 | 70.5 | 6.9 | ||

| 2005 | <8 years | 26.7 | 55.9 | 33.2 | 6.9 | 8.7 |

| ≥12 years | 50 | 15.3 | 72.5 | 6.9 | ||

| 2006 | <8 years | 28.4 | 55.0 | 33.5 | 6.8 | 8.5 |

| ≥12 years | 53.7 | 15.4 | 73.5 | 6.9 | ||

| 2007 | <8 years | 29.8 | 55.7 | 34.5 | 6.5 | 8.2 |

| ≥12 years | 54 | 14.7 | 74.8 | 7.0 | ||

| 2008 | <8 years | 31.1 | 55.0 | 35.4 | 7.0 | 8.1 |

| ≥12 years | 54.6 | 14.7 | 75.9 | 7.2 | ||

| 2009 | <8 years | 32.1 | 53.9 | 35.9 | 7.6 | 8.1 |

| ≥12 years | 56.1 | 14.5 | 77.6 | 7.1 | ||

| 2010 | <8 years | 32.2 | 54.6 | 37.4 | 7.2 | 7.9 |

| ≥12 years | 56.2 | 14.0 | 79.2 | 7.1 | ||

| 2011 | <8 years | 28.9 | 55.5 | 37.8 | 10.9 | 8.1 |

| ≥12 years | 57.5 | 14.1 | 82.3 | 9.1 | ||

| 2012 | <8 years | 28.6 | 54.6 | 37.4 | 13.0 | 8.0 |

| ≥12 years | 28.9 | 14.7 | 83.5 | 10.4 | ||

| 2013 | <8 years | 28.8 | 47.7 | 38.1 | 12.2 | 7.9 |

| ≥12 years | 58.2 | 14.7 | 83.0 | 9.6 |

*No data available.

(Source: MS/SVS/DASIS - Information System on Live Births).

The findings point out a gradual decrease in the frequency of women with low educational attainment, from 55.4% in 1996 to 18.5% in 2013. Accordingly, there was an increase in the frequency of women with high educational attainment, from 7.2% in 1996 to 24.4% in 2013 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Secular trend of maternal educational attainment in Brazilian state capitals, 1996–2013 (Source: MS/SVS/DASIS - Information System on Live Births).

| Year of birth | Maternal educational attainment | |

|---|---|---|

| <8 years, n (%) | ≥12 years, n (%) | |

| 1996 | 293,937 (55.4) | 38,359 (7.2) |

| 1997 | 362,848 (52.9) | 54,279 (7.9) |

| 1998 | 353,879 (52.1) | 52,622 (7.8) |

| 1999 | 258,147 (48.4) | 71,601 (13.4) |

| 2000 | 346,399 (49.6) | 117,359 (16.8) |

| 2001 | 318,397 (46.9) | 116,384 (17.1) |

| 2002 | 290,745 (43.9) | 117,172 (17.7) |

| 2003 | 270,388 (40.7) | 119,775 (18.0) |

| 2004 | 248,155 (37.4) | 128,457 (19.4) |

| 2005 | 235,518 (35.9) | 127,694 (19.5) |

| 2006 | 213,062 (32.6) | 136,235 (20.8) |

| 2007 | 194,767 (30.2) | 140,328 (21.8) |

| 2008 | 181,329 (27.7) | 150,389 (22.9) |

| 2009 | 171,939 (26.2) | 152,963 (23.4) |

| 2010 | 159,087 (24.4) | 158,829 (24.3) |

| 2011 | 148,315 (22.3) | 152,506 (22.9) |

| 2012 | 132,038 (19.9) | 153,959 (23.2) |

| 2013 | 122,796 (18.5) | 161,894 (24.4) |

| Overall | 4,301,746 (36.7) | 2,150,805 (18.4) |

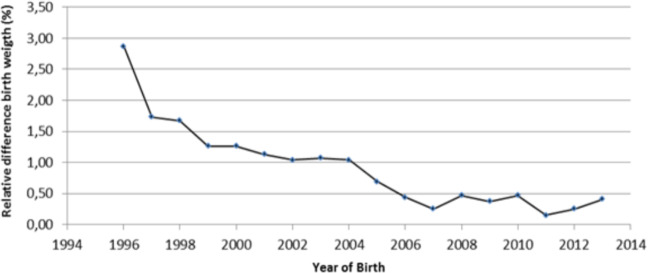

The absolute difference in mean birth weight among infants born to mothers with high vs. low educational attainment was 90.22 g in 1996, gradually decreasing to 5.05 g in 2011—the smallest difference for the whole period of interest. The relative difference also decreased, from 2.87% in 1996 to 0.41% in 2013 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Secular trends of mean birth weight and its relative difference according to maternal educational attainment, 1996–2013 (Source: MS/SVS/DASIS - Information System on Live Births).

| Year of birth | Birth weight (g) | Birth weight (g), stratified by maternal educational attainment | Relative difference (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <8 years | ≥12 years | |||

| 1996 | 3188 (528.4) | 3160 (532.3) | 3251 (504.6) | 2.87 |

| 1997 | 3179 (532.1) | 3162 (537.4) | 3217 (506.4) | 1.73 |

| 1998 | 3173 (530.1) | 3155 (536.7) | 3208 (504.0) | 1.67 |

| 1999 | 3183 (529.4) | 3169 (534.7) | 3209 (507.6) | 1.26 |

| 2000 | 3186 (530.2) | 3173 (534.2) | 3213 (517.1) | 1.26 |

| 2001 | 3176 (530.6) | 3166 (537.6) | 3202 (507.9) | 1.13 |

| 2002 | 3172 (531.5) | 3161 (539.9) | 3194 (510.9) | 1.04 |

| 2003 | 3161 (530.8) | 3149 (536.9) | 3183 (512.9) | 1.07 |

| 2004 | 3167 (534.5) | 3155 (545.5) | 3188 (512.7) | 1.04 |

| 2005 | 3177 (535.7) | 3167 (547.5) | 3189 (511.5) | 0.69 |

| 2006 | 3181 (540.6) | 3173 (554.5) | 3187 (514.3) | 0.44 |

| 2007 | 3180 (537.7) | 3173 (551.9) | 3181 (513.6) | 0.25 |

| 2008 | 3184 (540.4) | 3173 (556.9) | 3188 (514.8) | 0.47 |

| 2009 | 3181 (541.6) | 3170 (559.4) | 3182 (515.0) | 0.37 |

| 2010 | 3179 (537.7) | 3165 (557.3) | 3180 (511.1) | 0.47 |

| 2011 | 3180 (537.8) | 3166 (560.0) | 3171 (509.0) | 0.15 |

| 2012 | 3187 (540.5) | 3170 (562.2) | 3178 (507.5) | 0.25 |

| 2013 | 3187 (538.7) | 3166 (563.4) | 3179 (505.9) | 0.41 |

| Overall | 3179 (535.0) | 3164 (544.1) | 3189 (511.3) | 0.78 |

Data given as mean (SD) unless otherwise noted.

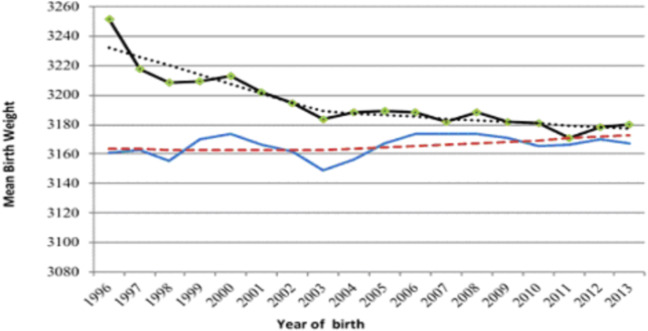

Mean birth weight among neonates born to mothers with high educational attainment declined steadily throughout the study period, while remaining stable among infants born to mothers with low schooling, with only a slight increase from 2005 onward (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Secular trends and annual mean birth weight of neonates born to mothers with high and low educational attainment, 1996–2013. The Fig. 1 shows the secular trends and annual mean birthweight of neonates born to mothers with high and low educational attainment in Brazilian state capitals from 1996 to 2013. In this figure, the curves of the mean weight of newborns born to mothers with high (“Mean_high”) and low (“Mean_low”) education are presented, as well as the secular trends of average weight of newborns born to mothers with discharge (“Jp high”) and low (“Jp low”) education, assessed through Joinpoint Regression. Each of these curves has different outlines and colors marked each year. It is possible to observe that the mean birth weight among neonates born to mothers with high educational attainment declined steadily throughout the study period, while remaining stable among infants born to mothers with low schooling, with only a slight increase from 2005 onward.

The relative difference in mean birth weight between the two extremes of maternal education showed a downward trend over the study period (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Secular trend of relative difference in mean birth weight among neonates born to mothers with high and low educational attainment, 1996–2013. The Fig. 2 shows the secular trend of relative difference in mean birth weight among neonates born to mothers with high and low educational attainment in Brazilian capitals from 1996 to 2013. This figure shows a single curve constructed from the difference between the mean birth weight of newborn children of mothers with higher education and the mean birth weight of newborn children of mothers with less education, year by year. This relative difference in mean birth weight between the two extremes of maternal education showed a downward trend over the study period.

Table 5 presents the means of birth weight differences of neonates born to mothers with high vs. low educational attainment, adjusted for covariables, in a sequential linear mixed model in the two different periods of analysis.

Table 5.

Mixed linear models with estimates of the annual difference in birth weight (g) among singleton neonates born alive to mothers living in Brazilian capitals with low versus high (reference) educational attainment, adjusted for covariates, in 1996–2003 and 2004–2013.

| Model | Low vs High educational attainment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996–2003 | 2004–2013 | |||||

| Difference in birth weight (g) | 95%CI | P | Difference in birth weight (g) | 95%CI | P | |

| a | 11.42 | (9.04; 13.81) | <0.001 | 1.47 | (0.43; 2.52) | 0.005 |

| b | 10.37 | (7.79; 2.95) | <0.001 | 2.25 | (1.10; 3.41) | <0.001 |

| c | 10.76 | (7.37; 4.14) | <0.001 | 1.63 | (0.19; 3.08) | 0.02 |

| d | 14.63 | (11.67; 17.59) | <0.001 | 3.60 | (2.12; 5.09) | <0.001 |

| e | 10.63 | (8.43; 12.84) | <0.001 | 1.03 | (0.04; 2.01) | 0.04 |

| f | 10.80 | (6.32; 15.28) | <0.001 | 1.03 | (−0.77; 2.84) | 0.26 |

aAdjusted for geographic region (place of birth): North (reference), Northeast, Central West, Southeast, and South.

bAdjusted for maternal age: 18–34 years (reference).

cAdjusted for number of previous live births: multiparous (reference). dAdjusted for number of antenatal visits: ≥ 7 (reference).

eAdjusted for length of gestation: ≥37 weeks (reference).

fAdjusted for type of delivery: cesarean section (reference).

In both periods, the number of antenatal visits (Model d) reduced the inequality between birth weight means in the two extremes of maternal education. Maternal age (Model b) had a negative effect, mainly in the second period (2004–2013), increasing the inequality in means of birth weight between the two extremes of maternal education. The covariables number of children, gestational age, and mode of delivery did not show any effect on the differences in birth weight means between the two groups of educational attainment during the study period.

Discussion

The results of this study showed a significant decline in mean of birth weight among infants born to mothers with a higher education level, leading to a significant reduction of general mean of birth weight during the time series. In terms of inequality in means of birth weight according to maternal education, we present a scenario compatible with the hypothesis of similarities in the inequality proposed for us previously, in which intense use of technologies and care coexisting with lack of access to them can lead a similar outcome9,27,28. Besides, the general increase in maternal education could contributed to amplify the severity of inequality between the two extremes of social, even though we noticed a narrowing trend of the outcome. In this case, the less educated mothers represent the most vulnerable social group in the country leading to an scarce access to health care and educational policies during the study period.

In addition, several maternal and child health indicators—including number of antenatal visits, multiparity, and the teenage pregnancy rate—showed overall improvement during the study period29. In contrast, there was an increase in primiparous women aged 35 or older, which has been associated with the increase in cesarean sections and premature births in Brazil8,30,31.

Other factors could be playing a significant role in this scenario, such as improvements in income distribution, with a general reduction in poverty leading to less maternal malnutrition, better quality of health care, and increased access to health care, especially for underprivileged social groups31. Besides, social programs, such as conditional cash programs, showed significant impact on infant health leading to reduction of infant mortality in less privileged communities32.

However, these positive factors did not produce a detectable effect on birth weight for women in unfavorable socioeconomic conditions, possibly indicating that this group has experienced extreme social exclusion and marginalization. Thus, considering this scenario, the stability of mean birth weight in the less educated group can be considered a net positive.

The effect of the number of antenatal visits on birth weight could be explained in two different directions according to educational level. For more educated mothers, antenatal care can be associated with intensive use of new technologies, such as in vitro fertilization, cesarean section, and ultrasound, leading to possible reductions in mean birth weight even without an increase in preterm birth rates. In mothers with lower schooling, expanded access to antenatal care can lead to better care of basic health needs, contributing to a reduction in acute illness and increased vaccination and nutritional follow-up rates29–31.

Antenatal care has long been considered an important factor related to birth weight. Inadequate numbers of antenatal visits are associated with low birth weight33–35, while increased access to antenatal care is associated with improved birth weight and other favorable pregnancy outcomes27. Mothers who attended fewer than 6 visits had a relative risk for low birth weight of 2.47 compared to those who attended 6 or more visits, even after adjustments for income and maternal education36. Six or more antenatal visits were associated with better outcomes for pregnant women with hypertensive disorders, while fewer visits or no antenatal care whatsoever were related to stillbirth and perinatal death, as well as higher risk of urinary tract infections, chorioamnionitis, and streptococcal vaginitis37,38.

The steady increase in rates of cesarean section presented influence in reduction in the difference in mean birth weight in both study periods, but more so in the second period proportionally. These increases occurred in women at both extremes of maternal education, but in those with lower educational attainment. The greater proportional increase in CS rates in this less privileged group of women could represent significant improvement in access to adequate health care, instead of excess of intervention, amplifying fetal survival, initially for heavy newborns. Brazil has one the highest rates of cesarean section in the world (52%)39, which has been associated with high rates of preterm birth35. This practice may also be associated with changes in the concept of fetal viability and interventions to prevent fetal deaths10,40.

Preterm births also have played a role in the birth weight trends observed herein, especially in the group of mothers with higher educational attainment. A study that evaluated preterm births between 2000 and 2010 in the most developed areas of Brazil suggested that successful interventions increased the rate of preterm live births by 45.2%40. Likewise, changes in the profile of pregnant women in the country, with an increase in the number of mothers aged 35 or older, have increased the risk of pre-existing health conditions and complications during pregnancy, such as hypertensive disorders40,41. This factor could be related to the decrease in mean birth weight observed, and has been previously described as the “low birth weight paradox”, whereby better socioeconomic development is associated with a higher rate of low birth weight28.

Limitations of this study include the lack of information about preexisting maternal clinical background, obstetric diseases, and intercurrent events during pregnancy. Data on pre-gestational body mass index, smoking, alcohol intake, psychoactive drug use, and maternal nutrition were not available. Inaccurate recording of gestational age in weeks and the high rate of incompleteness of the variable race/skin color made the inclusion of these variables in the study impossible.

On the other hand, the national scope of this study, the number of live births included in the analyses (more than 6 million) and its representativeness within the Brazilian population, the 18-year period of analysis (from 1996 to 2013), and the acknowledgment of maternal obstetric characteristics associated with birth weight are among the strengths of this study.

These results reflect the demographic, epidemiological, and perinatal transitions in the country over the last two decades, which have had an impact on mean birth weight. Similar trends have been reported in other countries, such as the United States and China, with decreases in birth weight in the last year10,12,20. Social advances and improvements in maternal education and maternal and child care have failed to exert a positive impact on birth weight, probably due to increased medical and technological interventions at all maternal education levels. Besides, the limited change in mean birth weight observed among infants born to women in unfavorable socioeconomic conditions may suggest that advances have not reached the most vulnerable strata of society.

In conclusion, despite a slight increase of mean birth weight among mothers with low education, this study indicates that the reduction of social inequalities in birth weight in Brazil came at the expense of worse outcomes in the better-off group, as opposed to improvements in mothers with low educational attainment. These findings suggest that the current epidemiological profile of birth outcomes in Brazil is characterized by the presence of “equality in inequality”, whereby similar outcomes occur as a result of differential effects of interventions and different social scenarios, leading to a merely apparent reduction of social inequality between extreme social strata.

Finally, the results found allow us to affirm that the reduction of inequality in pregnancy outcomes over time in Brazil is mostly attributable to a worsening scenario for mothers who are better off rather than to improvements for the most vulnerable group of mothers.

Acknowledgements

Financial support was provided by the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre Research and Events Incentive Fund (FIPE-HCPA).

Author contributions

S.S. designed the original research protocol, processed and analyzed data, and wrote the preliminary version of the manuscript; V.N.H. processed and organized the database and performed the statistical analyses; C.H.S. participated in writing, formatting, final revision, and submission of the manuscript; M.Z.G. contributed to the design of the research protocol and wrote the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hass S. Trajectories of functional health: the ‘long arm’ of childhood health and socioeconomic factors. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008;66(4):849–861. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu N, et al. Neighbourhood family income and adverse birth outcomes among singleton deliveries. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2010;32(11):1042–1048. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34711-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jafari F, Eftekhar H, Pourreza A, Mousavi J. Socio-economic and medical determinants of low birth weight in Iran: 20 years after establishment of a primary healthcare network. Public Health. 2010;124(3):153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferré C, Handler A, Hsia J, Barfield W, Collins JW., Jr. Changing trends in low birth weight rates among non-Hispanic black infants in the United States, 1991–2004. Matern. Child Health J. 2011;15:29–41. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0570-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo ZC, Wilkins R, Kramer MS. Effect of neighbourhood income and maternal education on birth outcomes: a population-based study. CMAJ. 2006;174(10):1415–1420. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young R, Weinberg J, Vieira V, Aschengrau A, Webster TF. A multilevel non-hierarchical study of birth weight and socioeconomic status. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2010;9:36. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-9-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silvestrin S, et al. Maternal education level and low birth weight: a meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. 2013;89(4):339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Souza Buriol VC, Hirakata V, Goldani MZ, Da Silva CH. Temporal evolution of the risk factors associated with low birth weight rates in Brazilian capitals (1996-2011) Popul. Health Metr. 2016;14:15. doi: 10.1186/s12963-016-0086-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silva AAM, et al. The epidemiologic paradox of low birth weight in Brazil. Rev. Saude Publica. 2010;44(5):767–775. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102010005000033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo Y, et al. Changes in birth weight between 2002 and 2012 in Guangzhou, China. PLoS One. 2014;9:e115703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mbazor OJ, Umeora OUJ. Incidence and risk factors for low birth weight among term singletons at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital (UBTH), Benin City, Nigeria. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2007;10(2):95–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickute J, et al. Maternal socio-economic factors and the risk of low birth weight in Lithuania. Medicina (Kaunas). 2004;40(5):475–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen HT, Eriksson B, Tran TK, Nguyen CT, Ascher H. Birth weight and delivery practice in a Vietnamese rural district during 12 year of rapid economic development. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Assefa N, Berhane Y, Worku A. Wealth status, mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) and antenatal care (ANC) are determinants for low birth weight in Kersa, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell EE, et al. Socioeconomic status and adverse birth outcomes: a population-based Canadian sample. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2018;50:102–113. doi: 10.1017/S0021932017000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haidar FH, Oliveira UF, Nascimento LFC. Maternal educational level: correlation with obstetric indicators. Cad. Saude Publica. 2001;17(4):1025–1029. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2001000400037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi L, et al. Primary care, infant mortality, and low birth weight in the states of the USA. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2004;58(5):374–380. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.013078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu Y, Zhang J, Lu X, Xi W, Li Z. Secular trends of macrosomia in southeast China, 1994–2005. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:818. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donahue SM, Kleinman KP, Gillman MW, Oken E. Trends in birth weight and gestational length among singleton term births in the United States: 1990–2005. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;115(2 Pt 1):357–364. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cbd5f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.United Nations Children’s Fund – UNICEF, https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/low-birthweight/ (2019).

- 21.Brazil. Department of Health Situation Analysis. Health Brazil 2010: Health analysis and selected evidences on impact of health surveillance action 1-372 (Ministry of Health, 2011).

- 22.Romero DE, Cunha CBD. Evaluation of quality of epidemiological and demographic variables in the Live Births Information System, 2002. Cad. Saude Publica. 2007;23(3):701–714. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2007000300028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silvestrin S, De Souza Buriol VC, Da Silva CH, Goldani MZ. Cad. Saude Publica. 2018;34(2):e:00039217. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00039217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hart JT. The inverse care law. Lancet. 1971;1(7696):405–412. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(71)92410-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.United Nations Development Program in Brazil – PNUD http://www.undp.org/content/brazil/en/home/countryinfo/ (2019).

- 26.Fausto MA, Carneiro M, Antunes CMF, Pinto JA, Colosimo EA. Mixed linear regression model for longitudinal data: application to an unbalanced anthropometric data set. Cad. Saude Publica. 2008;24(3):513–524. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2008000300005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldani MZ, Barbieri MA, Silva AA, Bettiol H. Trends in prenatal care use and low birthweight in southeast Brazil. Am. J. Public Health. 2004;94(8):1366–1371. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.8.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diniz C, Grilo S. Gender, maternal health and the perinatal paradox. Rev. Bras. Crescimento Desenvolvimento Hum. 2009;19(2):313–326. [Google Scholar]

- 29.United Nations Children’s Fund – UNICEF Brazil, https://www.unicef.org/brazil/pt/media_25849.html (2018).

- 30.Hernandez AR, Da Silva CH, Agranonik M, Quadros FM, Goldani MZ. Analysis of infant mortality trends and risk factors in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil, 1996-2008. Cad. Saude Publica. 2011;27(11):2188–2196. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2011001100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brazil. Department of Health Situation Analysis. Health Brazil 2011: an analysis of the health situation and the surveillance of the woman’s health 1-444 (Ministry of Health, 2012).

- 32.Rasella D, Aquino R, Santos CA, Paes-Sousa R, Barreto ML. Effect of a conditional cash transfer programme on childhood mortality: a nationwide analysis of Brazilian municipalities. Lancet. 2013;382(9886):57–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60715-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernardes A. C. F. et al. Inadequate prenatal care utilization and associated factors in São Luís, Brazil. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 14(266), 10.1186/1471-2393-14-266 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Rosa CQ, Silveira DS, Costa JSD. Factors associated with lack of prenatal care in a large municipality. Rev Saude Publica. 2014;48(6):977–984. doi: 10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048005283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brazil. Secretariat of Health Surveillance. Health Brazil 2014: an analysis of health situation and external causes 1-462 (Ministry of Health, 2015).

- 36.Fonseca C. R. B., Strufaldi M. W. L., Carvalho L. R. & Puccini R. F. Adequacy of antenatal care and its relationship with low birth weight in Botucatu, São Paulo, Brazil: a case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 14(255), 10.1186/1471-2393-14-255 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Veloso HJF, et al. Low birth weight in São Luís, northeastern Brazil: trends and associated factors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wehby GL, Murray JC, Castilla EE, Lopez-Camelo JS, Ohsfeldt RL. Prenatal care effectiveness and utilization in Brazil. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24:175–188. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monteiro CA, Benicio MHA, Ortiz LP. Secular trends in birth weight in São Paulo city, (1976-1998) Rev Saude Publica. 2000;34(Suppl. 6):26–40. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102000000700006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barbosa IR, et al. Maternal and fetal outcome in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: the impact of prenatal care. Ther. Adv. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015;9(4):140–146. doi: 10.1177/1753944715597622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mizumoto BR, et al. Quality of antenatal care as a risk factor for early onset neonatal infections in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2015;19(3):272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]