Abstract

Individuals with serious mental illness (SMI) experience significant premature mortality due to somatic conditions but often receive sub-optimal somatic care, but little research has been done to understand how general medical clinicians’ attitudes may affect care provision or health outcomes. This review describes general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward people with SMI, compares these attitudes to attitudes among mental health clinicians or toward individuals without SMI, and examines the relationship between attitudes and clinical decision making. 16 studies were reviewed. General medical clinicians reported negative attitudes toward individuals with SMI. These attitudes were generally more negative than attitudes among mental health clinicians and were consistently more negative when compared to attitudes toward individuals without SMI. Three studies conducted in the U.S. suggest that these negative attitudes have an adverse effect on clinician decision making.

Keywords: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, stigma, attitudes, somatic

Introduction

Individuals with serious mental illnesses (SMIs) such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression die 10–20 years earlier than individuals in the general population.1–3 Excess mortality in this population is tied to higher rates of, and worse outcomes for, physical health conditions such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory illness, and diabetes mellitus.4–6 Despite the need for somatic health care to address these conditions, the literature shows that many individuals with SMI receive sub-optimal quality of medical care.7 For example, studies have shown that relative to people without SMI, individuals with SMI are less likely to receive preventive care8 and guideline-concordant treatment for diabetes9 or stroke10 and are more likely to experience adverse patient safety events during general medical hospitalizations.11

Across cultures and countries, the general public endorses negative attitudes toward individuals with SMI. One study on attitudes of the general public in 16 countries suggested that despite cultural and language differences and knowledge of disease etiology and efficacious treatment, there is a common “backbone” of stigma toward individuals with schizophrenia or depression.12 While magnitude of endorsement of stigmatizing attitudes varied, there was a common expression of discomfort interacting with individuals with schizophrenia or depression and fear of their being violent driving negative attitudes across cultures.12

Clinicians’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI are an important but little-studied factor that may affect somatic care provision and health outcomes in these consumers. The relationship between clinicians’ attitudes and disparities in healthcare provision and resultant health outcomes has been studied in other frequently stigmatized groups including racial or ethnic minorities and gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) individuals.13–16 These studies have found that negative clinician attitudes affect health disparities in these populations through two pathways: (1) by negatively influencing clinical decision making, e.g. one study showed that negative implicit attitudes made clinicians less likely to recommend thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction to black patients than to white patients17 and (2) by negatively influencing patient-provider communication, e.g. one study showed higher rates of physician-dominated communication in visits with black patients versus white patients.13 Poor patient-provider communication is linked to lower rates of treatment adherence or care-seeking behavior among patients and lower patient satisfaction with the information provided.13–16,18,19

In studies examining their perceptions of both mental and somatic healthcare, consumers with SMI have reported experiencing diagnostic overshadowing, prognostic negativity, and paternalistic treatment, which may be manifestations of negative clinician attitudes toward consumers with SMI.4,20–22 To date, however, little is known about the attitudes of general medical clinicians toward individuals with SMI. A recent review by Henderson et al.23 examined studies of the attitudes of general medical and mental health clinicians toward individuals with mental illness with a focus on interventions to decrease stigma. This article found negative attitudes among general medical clinicians toward individuals with mental illness and the authors concluded that stigma-reducing interventions would be especially beneficial for mental health clinicians, men, and clinicians early in their career or with burnout.23

This scoping review builds on Henderson et al.’s review to conduct a review of studies of general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI. Henderson and colleagues23 did not focus purely on SMI, but included studies examining clinicians’ attitudes toward people with substance use disorders or mental illness generally. This is an important distinction as stigmatizing attitudes differ across diagnoses24 and may be more negative toward individuals with SMI (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression) compared to individuals with more common disorders such as anxiety or depression, as SMIs are less common and are associated with higher levels of functional impairment. Further, in their review, Henderson et al. only included studies that (1) compared attitudes between one or more groups of health professionals (e.g. psychiatrists or general internists) and a non-medical group (e.g. general population or students) or (2) compared health professional attitudes toward individuals with mental illness to those without mental illness.23 In contrast, this review included studies measuring general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward persons with SMI broadly, including surveys that did not make the comparisons required for inclusion in Henderson et al.’s work. Due to these differing inclusion criteria, this review includes 10 studies not previously reviewed by Henderson and colleagues.23

This scoping review maps the literature on general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI. Scoping review methodology was selected as, unlike systematic reviews or meta-analysis, it allowed for an iterative process for data selection and knowledge synthesis, which best fit the diversity of samples and methods used to assess these attitudes as well as the cultural and language differences between studies.25 This review had four objectives: (1) to describe attitudes toward people with SMI among general medical clinicians, (2) to compare attitudes toward individuals with SMI among general medical and mental health clinicians (in studies where such a comparison was made), (3) to compare attitudes of general medical clinicians toward people with SMI versus people with somatic health conditions (in studies where such a comparison was made), and (4) to examine the relationship between general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI and clinical decision making.

Methods

Studies included in this review were required to meet the following criteria: (1) published in English; (2) published between 1997 and 2018; (3) used quantitative measures; and (4) measured general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI. SMI is federally defined as “a diagnosable mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder that causes serious functional impairment that substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities.”26 For this study, inclusion was based on diagnoses that are generally associated with functional impairment, and therefore SMI (i.e., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression), as most studies used diagnosis to define their measures. Studies that measured both general medical and mental health clinicians’ attitudes were included if they reported measures of attitudes toward people with SMI separately for these two groups; studies that only reported attitudes among a combined group of general medical and mental health clinicians were excluded. Studies were excluded if they measured attitudes toward individuals with mental illness generally, toward individuals with diagnoses other than SMI (e.g., depression), or toward the disease itself rather than the individual.

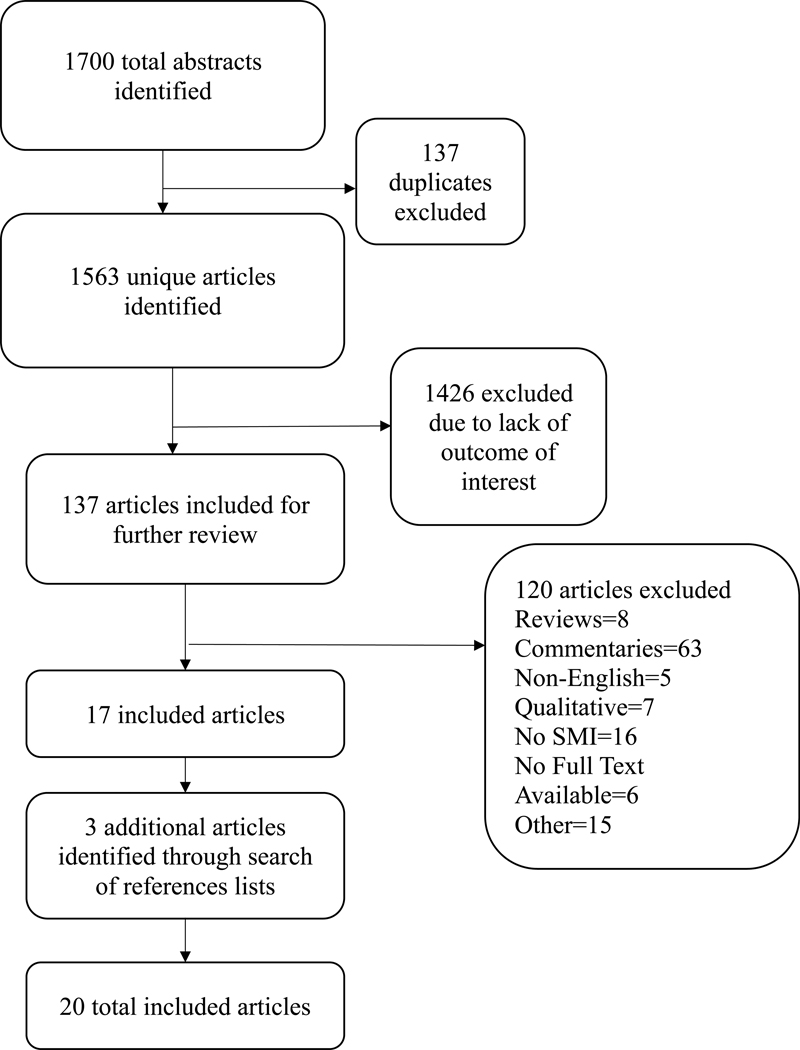

The following keywords were used to identify relevant articles from Embase, PsycINFO, PubMed, and SCOPUS: “physician-patient relations” or “quality of health care” or “communication barriers” or “attitude” AND “severe mental illness” or “major depression” or “schizophrenia” or “bipolar disorder” AND “physicians” or “general practitioners” or “health care providers” or “primary care providers”. Using this method, 1700 abstracts and 1563 unique articles were identified from a time period between 1997 to 2018; 381 from Embase, 283 from PsycINFO, 385 from PubMed, and 514 from SCOPUS. After exclusion criteria were applied, three additional studies were identified through a scan of reference lists of included articles. 20 unique articles reporting results from 17 studies were included in this review. See Figure 1 for a flow diagram of the search and selection process.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Search and Selection Process

A systematic process was used to extract study author, location, clinician sample, year of data collection, study method, and results from each study. Four categories of study results were extracted: (1) measures of the magnitude of general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI, such as perceived dangerousness; (2) measures comparing attitudes among general medical clinicians and mental health clinicians; (3) measures comparing general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI and individuals with chronic somatic conditions, such as diabetes or eczema; (4) measures of the association between general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI and clinical decision making.

Results

The 20 included articles were published between 1998 and 2017 (Table 1). Data for these studies was collected between 1995 and 2015. Of the 17 unique studies reported, three were conducted in the United Kingdom,27–29 two in Australia,30,31 two in Japan,32,33 two in Turkey,34,35 two in the United States,36–40 and one each in Hong Kong,41 India,42 Italy,43 Pakistan,44 Sri Lanka,45 and Sweden.46 Eight studies measured clinicians’ attitudes in response to written statements about individuals with SMI.28,32,33,35,43–46 Four of these used the survey created for the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Campaign (RCPC) by Crisp, et al.28,44–47 Nine studies measured attitudes in response to vignettes depicting an individual with SMI. Eight of these studies used written vignettes27,29–31,34,37,41,42 and one used video vignettes.40 Five studies measured attitudes toward individuals with major depression or schizophrenia,28,30,44–46 and the other twelve measured attitudes only toward individuals with schizophrenia.27,29,31–38,40–43 General medical clinician populations surveyed included physicians,27–30,32,34–38,40,41,43–45 nurses,31,34,36–38,46 medical students,28,42,44,45 academicians,34 and other non-psychiatric care workers such as health care assistants, case workers, or social welfare staff.33

Table 1.

Summary of included studies (N=17 studies)

| Author, Publication Year | Country | Sample | Year(s) Data Collected | Method SMI diagnoses are underlined |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aydin, 2003 | Turkey | 40 academicians, 40 resident physicians, & 40 nurses | 2001 | Survey of attitudes in response to Star’s vignettes1 depicting individuals with paranoid schizophrenia based on Arkar’s social distance scale2 and Eker’s questionnaire on expected burden3 |

| Bjorkman, 2008 | Sweden | 69 somatic care nurses: 44 registered nurses and 25 assistant nurses | Not described | Survey of attitudes in response to written statements about individuals with severe depression and schizophrenia based on the Swedish version of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Campaign (RCPC)i Survey4 |

| Chandramouleeswaran, 2017 | India | 57 nonpsychiatric medical residents | Jan.-March 2015 | Survey of attitudes in response to written vignettes depicting individuals with schizophrenia based on the Attitudes toward Mental Illness Questionnaire (AMIQ)5 |

| Fernando, 2010 | Sri Lanka | 574 medical students and 72 doctors from surgical and medical wards | April-Sep. 2008 | Survey of attitudes in response to written statements about individuals with severe depression and schizophrenia based on the RCPC Survey4 |

| Hori, 2011 | Japan | 112 physicians other than psychiatrists | May-June 2009 | Survey of attitudes in response to written statements about individuals with schizophrenia based on Uçok et al.’s questionnaire6 and other literature |

| Ishige, 2005 | Japan | 76 non-psychiatric care workers (health care assistants, medical case workers, and social welfare workers) | 2001–2002 | Survey of attitudes toward in response to statements related to individuals with schizophrenia based on the semantic differential technique7 and the modified Social Rejection Scale (m-SRS)8 |

| Jorm, 1999 | Australia | 872 general practitioners | May-June 1996 | Survey of attitudes in response to a written vignette depicting a person with either major depression or schizophrenia |

| Lam, 2013 | Hong Kong | 500 primary care physicians | Dec. 2009-April 2010 | Survey of attitudes in response to a written vignette depicting a person with schizophrenia |

| Lawrie, 1998 | United Kingdom | 166 general practice physicians | Not described | Survey of attitudes in response to a written vignette depicting a woman with schizophrenia who has a 5-year-old daughter |

| Magliano, 2017 | Italy | 430 general practitioners | June 2013-March 2014 | Survey of attitudes in response to a statements related to a diagnosis or clinical description of a person with schizophrenia based on a revised version of the Opinion on Mental Illness Questionnaire9 |

| Mittal, 2014; Corrigan 2014; Sullivan 2015; Smith, 2017ii | United States | 146 primary care clinicians: 91 nurses & 55 physicians | Aug. 2011-April 2012 | Survey of attitudes in response to a written vignette depicting a man with schizophrenia seeking care for low back pain |

| Mukherjee, 2002 | United Kingdom | 184 doctors & 335 medical students | Not described | Survey of attitudes in response to written statements about individuals with severe depression and schizophrenia based on the RCPC Survey4 |

| Naeem, 2006 | Pakistan | 99 doctors & 200 medical students | Not described | Survey of attitudes in response to written statements about individuals with severe depression and schizophrenia based on the RCPC Survey4 |

| Noblett, 2015 | United Kingdom | 52 general hospital doctors | Not described | Survey of attitudes in response to written vignettes depicting individuals with schizophrenia based on the RCPC Survey4 and the Attitudes to Mental Illness Questionnaire5 |

| Rogers, 1998 | Australia | 30 general nurses | May-Aug. 1995 | Survey of attitudes, asking what respondents ‘should’ or ‘would’ do in response to a modified version of the Discrimination and Devaluation Scale10 and written vignettes depicting an individual with schizophrenia in a social setting and moving in to a flat next door |

| Uçok, 2006 | Turkey | 106 general practitioners | Not described | Survey of attitudes in response to “general myths” associated with individuals with schizophrenia |

| Welch, 2015 | United States | 256 primary care physicians | 2010 | Survey of attitudes in response to video vignettes depicting a man or a woman with schizophrenia with normal affect or schizophrenia with bizarre affect |

This survey is referred to by multiple names in the literature. Here we refer to it as the “Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Campaign (RCPC) Survey” Crisp, A. H., Gelder, M. G., Rix, S., Meltzer, H. I., & Rowlands, O. J. (2000). Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 177(1), 4–7.

These four publications use the same data set.

General medical clinicians’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI

Selected measures of medical clinicians’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI are described below. Appendix 1 contains detailed information on each measure.

Perceived dangerousness was measured by 12 of the 17 studies.27–30,32,35,37,40,43–46 In general, beliefs about dangerousness were more negative toward individuals with schizophrenia compared to those with major depression. The four studies using the RCPC survey47 reported levels of agreement ranging from 49%−55% (mean score: 4.3) for beliefs that individuals with schizophrenia were dangerous to others and agreement from 12%−28% (mean score: 1.6) for beliefs that individuals with major depression were dangers to others.28,44–46 One study reported that general practitioners in Australia rated individuals with major depression less likely to be violent than other patients (mean rating: −0.2) and those with schizophrenia more likely to be violent than other patients (mean rating: 0.1).30 Welch et al.40 found that attitudes on perceived dangerousness were more negative in response to vignettes depicting individuals with schizophrenia with bizarre affect (mean score: 7.6) compared to those depicting individuals with normal affect (mean score: 8.4). Magliano et al.43 found that the majority of general practitioners (79.5%) believed that individuals with schizophrenia become dangerous if they stop taking medication.

Nine of the studies reviewed included measures on provider perceptions of clinical encounters and disease management.27–29,40,41,43–46 Most clinicians believed that individuals with schizophrenia or major depression could improve with treatment or recover.28,43–46 Two studies found that that while practitioners welcomed having individuals with schizophrenia on their patient panel, they also believed that these patients would take a lot of their time and would be unlikely to comply with treatment.27,41 On measures of ability to self-manage health, Welch and colleagues40 reported a slightly higher perceived ability for individuals with schizophrenia with normal affect (mean score: 11.5) compared to individuals with schizophrenia with bizarre affect (mean score:10.6) and Magliano et al.43 reported that the majority of general practitioners did not believe or only partially believed that individuals with schizophrenia were reliable in referring their mental (82.3%) or physical (77.1%) problems to medical doctors.

Desire for social distance was also measured in nine of the studies reviewed.31–35,37,40,42,43 Studies generally reported high desires for social distance among general medical clinicians and high perceptions of social distancing by others.43 In one study, none of the measures for social distance received positive responses from all three clinician groups surveyed.34 Welch and colleagues40 report a higher desire for social distance toward individuals with schizophrenia with bizarre affect (mean score: 9.6) compared to individuals with schizophrenia with normal affect (mean score: 10.7) among primary care physicians in the U.S. Rogers and Kashima31 measured social distance by measuring how nurses felt they “should” respond compared to how they “would” respond in social situations with individuals with schizophrenia. Overall scores were more negative for how nurses “would” actually respond (mean: 1189.9) compared to how they believed they “should” respond (mean: 1378.2).31

Five studies measured general medical clinicians’ perceptions of disease attribution. Of the four studies using the RCPC survey,47 belief that individuals with schizophrenia were to blame for their illness had high levels of endorsement (53.7% agreement) in only one study of clinicians in Pakistan.44 Other attitudinal measures were related to personal characteristics of those with SMI, such as unpredictability, being hard to talk or relate to, and abilities to maintain social relationships. All four of the RCPC surveys47 found negative attitudes relating to the measures “unpredictable” (70.8–84.9% agreement, mean score: 4.3) toward individuals with schizophrenia.28,44–46 Negative attitudes toward individuals with major depression were found in the domain “hard to talk to” (50.0–62.2% agreement, mean score: 3.5).28,44–46 Two studies also found that general practitioners and residents believed that individuals with major depression and schizophrenia are more likely to have poor friendships and less likely to have successful marriages relative to individuals without SMI.30,42

Comparisons of general medical clinicians’ vs mental health clinicians’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI

Comparisons between general medical clinicians’ and mental health clinicians’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI were made in seven studies (summarized in Table 2). Overall findings were mixed. Three studies32,33,37,39 reported more negative attitudes among general medical clinicians compared to mental health practitioners. Hori and colleagues32 compared attitudes toward individuals with schizophrenia among general medical physicians, psychiatrists, and psychiatric staff in Japan. All measures of attitudes were significantly more negative among the general medical clinicians compared to psychiatric staff and psychiatrists. The largest differences in attitudes were found on measures of beliefs that patients with schizophrenia could harm children (58.0% of general medical clinicians vs. 22.2% of psychiatrists) and are untrustworthy (36.6% vs 5.6%) and not wanting to have a neighbor with schizophrenia (41.4% vs. 11.1%).32 Also in Japan, Ishige and Hayashi33 found that both mental health nurses had more positive attitudes toward individuals with schizophrenia compared to non-psychiatric care workers in Japan. Compared to mental health nurses, non-psychiatric care workers reported significantly less accepting attitudes and greater desire for social distance.33 In the United States, Mittal et al.37 reported more negative attitudes among primary care nurses and physicians compared to mental health clinicians (nurses, psychiatrists, and psychologists) employed by five Veterans Affairs hospitals located in the southern U.S. Ratings on measures of provider stereotyping and attribution of mental illness were more significantly more negative among the general medical clinicians.37 Using the same data, Smith at al.,39 further divided the provider groups and found both primary care nurses and physicians reported significantly greater desire for social distance compared to psychologists and mental health nurses. Primary care physicians were also significantly more likely to endorse stereotypical beliefs toward individuals with schizophrenia compared to psychologists or mental health nurses.39

Table 2.

Comparisons of attitudes about consumers with serious mental illness among general medical clinicians to attitudes among mental health clinicians (N=7 studies)

| Author, publication year | Comparison of stigma measures in general medicine practitioners versus mental health specialists | Comparison summary | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bjorkman, 2008 | Somatic Care Nurses (n=69) | Psychiatric Care Nurses (n=51) | Mixed results | |||||||

| Mean measures of attitude on a scale of 1 (most positive) to 5 (most negative); mean (standard deviation) Severe Depression Danger to others: Unpredictable: Hard to talk to: Themselves to blame: Not improved if treated: Perceived as unusual: Pulling themselves together: Never recover: Schizophrenia Danger to others: Unpredictable: Hard to talk to: Themselves to blame: Not improved if treated: Perceived as unusual: Pulling themselves together: Never recover: |

1.6 (0.9) 3.1 (1.0) 3.5 (1.0) 1.6 (0.8) 1.4 (0.8) 3.7 (1.2) 2.2 (0.8) 1.6 (1.0) 3.6 (1.0)*** 4.3 (0.7)*** 3.8 (0.7)*** 1.3 (0.6) 2.0 (1.0) 4.4 (0.8) 1.8 (0.9) 3.5 (1.2) |

1.6 (0.7) 3.0 (1.0) 3.3 (0.8) 1.4 (0.7) 1.2 (0.7) 4.0 (1.1) 2.1 (0.7) 1.4 (0.6) 2.9 (0.9) 3.6 (0.8) 3.3 (0.8) 1.2 (0.5) 1.8 (1.0) 4.5 (1.0) 1.9 (0.7) 3.2 (1.3) |

||||||||

| Hori, 2011 | Physicians (n=112) | Psychiatric Staff (n=100) | Psychiatrists (n=36) | More negative attitudes among general medicine clinicians | ||||||

| Percentage of subjects who answered “I agree” Patients with schizophrenia can work: Would oppose if a relative would like to marry someone who has schizophrenia: Schizophrenia patients can be recognized by their appearance: Schizophrenia patients are dangerous: Would not like to have a neighbor with schizophrenia: Schizophrenia patients are untrustworthy: Schizophrenia patients could harm children: Schizophrenia patients should be kept in hospitals: |

82.1*** 76.8* 24.1*** 30.4*** 41.1** 36.6*** 58.0** 17.0*** |

87.0 86.0 47.0 18.0 44.0 25.0 54.0 11.0 |

97.2 75.0 41.7 2.8 11.1 5.6 22.2 0.0 |

|||||||

| Ishige, 2005 | Non-psychiatric care workers (n=229) | Public Health Nurses (n=83) | Psychiatric Nurses (n=261) | More negative attitudes among general medicine clinicians | ||||||

|

Mean score (standard deviation) Evaluation Scale Score (higher score indicates more accepting attitude): m-SRS Score (higher score indicates higher degree of distancing): |

6.3 (6.2)*** 22.2 (4.0)*** |

12.2 (6.3) 18.3 (3.9) |

9.9 (6.5) 21.0 (4.8) |

|||||||

| Jorm, 1999 | General Practitioners (n=872) | Psychiatrists (n=1128) | Clinical Psychologists (n=454) | Mixed results | ||||||

| Mean ratings on scale of −1 (less likely) to 1 (more likely)i Depression: Negative Outcomes Be violent: Have poor friendships: Depression: Positive Outcomes Understand other’s feelings: Have a good marriage: Be a caring parent: Be a productive worker: Be creative or artistic: Schizophrenia: Negative Outcomes Be violent: Have poor friendships: Schizophrenia: Positive Outcomes Understand other’s feelings: Have a good marriage: Be a caring parent: Be a productive worker: Be creative or artistic: |

−0.2 0.1 0.3 −0.2 0.0 −0.1 0.0 0.1 0.6 −0.4 −0.6 −0.4 −0.5 0.1 |

−0.2 0.0 0.5 −0.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.1 0.8 −0.5 −0.8 −0.6 −0.7 −0.2 |

−0.4 −0.2 0.4 0.1 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.0 0.6 −0.3 −0.6 −0.4 −0.5 0.0 |

|||||||

| Mittal, 2014 | Primary Care Providers (n=146) | Mental Health Providers (n=205) | More negative attitudes among general medicine clinicians | |||||||

| Mean (standard deviation) Desire for social distance score (range 5–20, higher number indicates greater desire for social distance from person with schizophrenia): Provider stereotyping score (range 9–63, higher number indicates more negative stereotype on semantic differential items such as valuable/worthless, clean/dirty, and safe/dangerous): Attribution of mental illness score (range 6–54, higher number indicates more negative attitudes and emotions, including endorsement of the idea that the patient is responsible for his condition, that he is dangerous, and feelings of anger and fear about the patient): |

11.6 (4.9) 28.6 (14.0)** 11.0 (9.4)* |

10.6 (4.3) 26.5 (9.9) 9.2 (5.3) |

||||||||

| Rogers, 1998 | General Nurses (n=30) | Psych. Nurses (n=31) | No difference in attitudes among general medicine and mental health clinicians | |||||||

| Mean prejudice score Low prejudice (11–21): High prejudice (22–55): Mean ‘should’, ‘would’, and prejudice scores (lower scores indicate more negative attitudes); mean (standard deviation) Would index (indicates how respondents would actually respond in a situation based on their personal thoughts and feelings): Thinking: Feeling: Behaving: Should index (indicates how respondents think they should respond in a situation based on personal standards): Thinking: Feeling: Behaving: Average of ‘Shoulds’ and ‘woulds’: Thinking: Feeling: Behaving: Total prejudice score: |

16.1 26.3 1189.9 (243.5) 380.9 (89.1) 368.9 (113.0) 440.2 (85.8) 1378.2 (210.3) 437.6 (84.7) 472.8 (90.5) 467.7 (67.1) 1284.1 409.3 420.8 454.0 22.5 |

16.7 25.8 1299.2 (216.8) 415.4 (78.3) 429.7 (93.7) 454.1 (80.8) 1335.0 (201.7) 425.1 (64.4) 459.8 (89.2) 450.1 (74.4) 1317.1 420.3 444.8 452.1 22.3 |

||||||||

| Smith, 2017 | Primary care nurse (n=91) | Primary care physician (n=55) | Mental health nurse (n=67) | Psychiatrist (n=62) | Psychologist (n=76) | More negative attitudes among general medicine clinicians | ||||

| Mean (standard error) Provider stereotyping (range 9–63, higher score indicates more negative attitude): Attribution of mental illness (range 6–54, higher score indicates more negative attributions): Social distance (range 5–20, higher score indicates a greater desire for social distance and more negative attitude): |

27.42 (1.00)* 10.55 (0.64) 11.31 (0.35) |

30.67 (1.04)* 11.57 (0.81) 12.06 (0.39)* |

26.49 (1.10) 9.03 (0.59) 10.72 (0.42) |

27.21 (.87) 9.88 (0.56) 11.37 (0.46) |

25.91 (0.76) 8.75 (0.33) 9.92 (0.32) |

|||||

p ≤0.05;

p≤0.01;

p≤0.001

P-values not reported

Two studies reported mixed results. The first compared attitudes between somatic and psychiatric care nurses toward individuals with major depression and schizophrenia in Sweden. While measures of attitudes toward individuals with major depression were similar between the two groups, general medical clinicians had more negative attitudes than mental health clinicians toward individuals with schizophrenia. Significant differences were reported found on beliefs that individuals with schizophrenia are dangerous (somatic care nurses: 3.6 vs. psychiatric care nurses: 2.9), unpredictable (4.3 vs. 3.6), and hard to talk to (3.8 vs. 3.3).46 The second study, conducted in Australia, found that clinical psychologists generally had more positive attitudes toward people with major depression compared to either general practitioners or psychiatrists. The greatest differences between general practitioners and clinical psychologists were found on beliefs that individuals with major depression are more likely to have poor friendships (general practitioner mean score: 0.1 vs. clinical psychologist mean score: −0.2) and less likely to have good marriages (−0.2 vs. 0.1) or be a productive worker (−0.1 vs 0.2). Attitudes toward individuals with schizophrenia were similar across the three groups.30 The final study reported no difference in attitudes toward individuals with schizophrenia between general nurses and psychiatric nurses in Australia.31

Comparisons of general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI vs somatic conditions

Five studies made comparisons between general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI and individuals with somatic conditions (summarized in Table 3). All five studies reported more negative attitudes toward individuals with SMI than toward individuals with somatic conditions. Two of the studies were performed in the U.S. Mittal and colleagues37 compared attitudes in response to written vignettes describing individuals with versus without schizophrenia. On all three measures, attitudes were more negative toward the individual depicted as having schizophrenia with significant differences found in provider stereotyping and attribution of mental illness scores.37 Welch et al.40 compared attitudes in response to video vignettes of individuals with schizophrenia with normal affect, schizophrenia with bizarre affect, and eczema. The most negative attitudes were directed toward individuals with schizophrenia with bizarre affect, with significant differences found on personal attributes and perceived dangerousness scores when compared to individuals with eczema. All four measures were more negative toward individuals with either schizophrenia description compared to individuals with eczema except ability to self-mange health (schizophrenia with normal affect mean score: 11.5 vs. eczema mean score: 11.4).40

Table 3.

Comparisons of general medical clinicians’ attitudes about consumers with serious mental illness versus those with somatic conditions (N=5 studies)

| Author, publication year | Comparison of measures of general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward patients with mental illness versus patients with somatic conditions | Comparison summary | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chandramouleeswaran, 2017 | Schizophrenia | Diabetic | ||||

| Attitude to mental illness questionnaire scores (higher score indicates more favorable attitude)i Minimum score Maximum score Mean score Standard deviation 95% CI |

−10.00 10.00 −2.14 4.43 −3.28–0.93 |

−3.00 10.00 7.54 3.02 6.71–8.24 |

More negative attitudes about patients with mental illness | |||

| Lawrie, 1998 | Schizophrenia | Diabetes | Healthy | More negative attitudes about patients with mental illness | ||

| Median measures of agreement on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 6 (complete); median (interquartile range) You would be happy to have this patient on your list: This person is likely to take up a lot of time: This patient is more likely to be violent than most patients: She is unlikely to comply with advice or treatment given: You would be concerned about the child’s welfare: She arouses your sympathy: |

5 (4–6)* 4 (3–5) 1 (0–3)* 2 (1–3) 3 (3–4)*** 4 (3–5) |

6 (5–6) 4 (3–5) 0 (0–1) 1 (0–3) 2 (1–3) 4 (3–5) |

6 (5–6) 4 (3–4) 1 (0–2) 2 (1–3) 3 (1–3) 4 (4–4) |

|||

| Mittal, 2014 | Schizophrenia vs. Nonschizophrenia | More negative attitudes about patients with mental illness | ||||

| Mean difference Desire for social distance score (range 5–20, higher number indicates greater desire for social distance from person): Provider stereotyping score (range 9–63, higher number indicates more negative stereotype on semantic differential items such as valuable/worthless, clean/dirty, and safe/dangerous): Attribution of mental illness score (range 6–54, higher number indicates more negative attitudes and emotions, including endorsement of the idea that the patient is responsible for his condition, that he is dangerous, and feelings of anger and fear about the patient): |

0.8 5.1** 2.1** |

|||||

| Noblett, 2015 | Schizophrenia | Diabetes | More negative attitudes about patients with mental illness | |||

| Mean attitude scores on a scale of −2 (most negative) to 2 (most positive)ii Comfortable seeing on own: Suspicious of reason: Hard to talk to: Dangerous: Unpredictable: |

0.5*** 0.6 0.3*** 0.2*** −0.3*** |

1.3 1.0 1.2 1.1 0.9 |

||||

| Welch, 2015 | Schizophrenia, Normal Affect | Schizophrenia, Bizarre Affect | Eczema | More negative attitudes about patients with mental illness | ||

| Least squares mean (standard error) Ability to self-manage health score (range 4–16, higher number indicates higher perceived ability to self-manage health): Personal attributes score, i.e. competence, intelligence, confidence, warmth, sincerity, and being good-natured (range 4–24, higher number indicates more positive attitude): Desire for social distance score (range 1–20, higher number indicates greater willingness to be socially connected with person with schizophrenia): Perceived dangerousness score (range 1–12, higher number indicates lower perception of dangerousness): |

11.5 (0.3) 17.8 (0.4) 10.7 (0.5) 8.4 (0.3) |

10.6 (0.3) 15.2 (0.4)*** 9.6 (0.5) 7.6 (0.3)*** |

11.4 (0.3) 17.9 (0.4) 11.3 (0.5) 9.6 (0.2) |

|||

p ≤0.05;

p≤0.01;

p≤0.001

P-values not reported.

Results presented in a graph. Numbers reported here are author’s interpretation.

Star SA. The public’s ideas about mental illness. 1955.

Arkar H. The social refusing of mental patients. J Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 1991;4:6-9.

Eker D. Attitudes toward mental illness: Recognition, desired social distance, expected burden and negative influence on mental health among Turkish freshmen. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 1989;24(3):146-150.

Crisp AH, Gelder MG, Rix S, Meltzer HI, Rowlands OJ. Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;177(1):4-7.

Luty J, Fekadu D, Umoh O, Gallagher J. Validation of a short instrument to measure stigmatised attitudes towards mental illness. The Psychiatrist. 2006;30(7):257-260.

Üçok A, Soyguer H, Atakli C, et al. The impact of antistigma education on the attitudes of general practitioners regarding schizophrenia. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2006;60(4):439-443.

Hoshigoe K. A study of the social attitudes of psychiatic hospital staffs towards the mentally disabled in Kagawa Prefecture. Jpn Bull Soc Psychiatry. 1994;2:93-104.

Trute B, Tefft B, Segall A. Social rejection of the mentally ill: a replication study of public attitude. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 1989;24(2):69-76.

Magliano L, Read J, Sagliocchi A, et al. “Social dangerousness and incurability in schizophrenia”: Results of an educational intervention for medical and psychology students. Psychiatry research. 2014;219(3):457-463.

Link BG, Cullen FT, Frank J, Wozniak JF. The social rejection of former mental patients: Understanding why labels matter. American journal of Sociology. 1987;92(6):1461-1500.

Two studies were conducted in the U.K. One compared attitudes toward individuals with controlled schizophrenia, controlled diabetes, and previously healthy individuals. Compared to individuals with diabetes, clinicians significantly more likely to report thinking that individuals with schizophrenia were more likely to be violent (schizophrenia median score: 1 vs. diabetes median score: 0), being less happy to have the patient on their list (5 vs. 6), and being more concerned about the welfare of the individual’s child (3 vs. 2).27 The second study compared attitudes toward individuals with schizophrenia and individuals with diabetes. Compared to those with diabetes, general medical clinicians had more negative attitudes toward individuals with schizophrenia on every measure, with significant differences on beliefs that patients with schizophrenia were unpredictable (schizophrenia mean score: −0.3 vs. diabetes mean score: 0.9), dangerous (0.2 vs. 1.1), and hard to talk to (0.3 vs. 1.2) as well as being less likely to be comfortable seeing the patient on their own (0.5 vs. 1.3).29 The fifth study, conducted in India, compared attitudes between individuals with schizophrenia and diabetes with medical students reporting more favorable attitudes toward patients with individuals with diabetes compared to those with schizophrenia.42

Association between clinicians’ attitudes and clinical decision making

Three U.S. studies36,38,40 and one Italian study43 examined the association between general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward people with SMI and clinical decision making. Using the study data reported by Mittal et al.,37 summarized above, Sullivan et al.38 and Corrigan et al.36 assessed the influence of clinician stigma and the influence of a schizophrenia diagnosis on clinicians’ decisions in five VA hospitals in the southeast and south central U.S. Sullivan and colleagues38 measured the relationship between vignette type (schizophrenia or no schizophrenia) and perceived treatment adherence, ability to read and understand health materials, and competence in managing health and provider referral to weight reduction, pain management, or sleep studies. They found that both general medical and mental health clinicians anticipated that individuals with schizophrenia would have lower levels of treatment adherence, competence in managing their health, and ability to understand treatment materials compared to otherwise identical patients without schizophrenia. Additionally, clinicians were less likely to say they would refer an individual with schizophrenia to a weight-reduction program compared to an individual without schizophrenia, but this relationship was not seen in responses related to referrals for pain-management programs or sleep studies.38

Using the same data, Corrigan et al.36 tested the relationship between stigma and health decisions accounting for familiarity with mental illness and provider discipline (general medical or mental health). They found that the relationship between negative attitudes and likelihood of treatment referral was partially mediated by perceived treatment adherence. Clinicians with more stigmatizing attitudes were less likely to believe that individuals with schizophrenia would adhere to treatment and therefore less likely to report they would refer consumers to specialists or refill medication prescriptions of a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory or a narcotic analgesic compared to individuals without schizophrenia. Familiarity with mental illness was significantly related to both provider discipline and negative attitudes, but the relationship between provider discipline and stigma characteristics was not significant.36

Welch et al.40 used a mixed methods approach to assess the influence of primary care clinicians’ attitudes difference on clinical diabetes management among internists or family practitioners working in Massachusetts. Clinicians responded to interview questions after viewing a video vignette and completing a survey. This study found relatively few differences in clinical actions based on clinicians’ attitudes. For consumers with schizophrenia with bizarre affect clinicians were more likely to say they would rely on other sources (charts or other clinicians) for patient information and would be more likely to enter “subjective impressions” in chart notes compared to patients with eczema, depression, or schizophrenia with normal affect.40

In Italy, Magliano et al.43 tested whether the relationships between any stigmatizing attitudes and differential conduct toward individuals with schizophrenia were mediated by the physician’s perception that those with schizophrenia were dangerous. Endorsing beliefs that individuals with schizophrenia need life-long pharmacological treatment, are unreliable in reporting health problems, and are kept at a social distance by others were significantly related to the perception of individuals with schizophrenia as dangerous. This perception of dangerousness, the belief that schizophrenia requires long-term pharmacological treatment, and the perception of others’ social distance were all significantly related to more restrictive, discriminatory behaviors in non-psychiatric hospital settings (e.g., separating individuals with schizophrenia from other patients).43

Discussion

General medical clinicians demonstrated negative attitudes toward individuals with SMI across all 17 studies spanning 11 countries included in this review.50,51 Measures of desire for social distance were frequently endorsed, with one study indicating that 100% of nurses would not like their sister marrying someone with schizophrenia.34 Measures of perceived dangerousness indicated that clinicians believed that individuals, especially those with schizophrenia, were more likely to be violent compared to those without SMI.27,29,30,37,40 Relative to mental health specialists, many general medical clinicians in the studies reviewed had more negative attitudes toward people with SMI.32,33,37,39,46 In addition, all five studies that compared general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI to those with somatic conditions found attitudes to be more negative toward consumers with SMI.27,29,37,40,42 The four studies that assessed the impact of clinician attitudes on clinical decision making suggest that negative attitudes adversely affect clinical decision making regarding somatic care for individuals with SMI.36,38,40,43 The negative attitudes, especially perceptions of dangerousness and desire for social distance, endorsed by general medical clinicians toward individuals with SMI were similar to those in the general public.50,51 As in the general public, negative attitudes were similar across cultures, reflecting the “backbone” of stigma described by Pescosolido and colleagues,12 and may be partially due to relatively less exposure of both general medical clinicians and the general public to individuals with SMI compared to mental health specialists.

Attitudes were measured in response to written vignettes about individuals with SMI in nine studies. Eight studies used written vignettes27,29–31,34,37,41,42 and one study used video vignettes.40 Vignettes lead respondents to answer attitudinal questions in response to a portrayal of a specific person with SMI, while attitudinal questions asked in the absence of vignettes allow clinicians to report their attitudes based on their own interpretation of people with SMI. Vignettes that portray individuals as symptomatic, e.g. actively experiencing delusions, and prior research suggests that such depictions increase stigma relative to depictions of people with successfully treated, asymptomatic SMI.52 In addition, vignettes – especially video vignettes – may introduce other stigmatizing attributes (e.g. race) that could affect the magnitude of the attitudes measured.24 Despite these limitations, findings of negative attitudes were consistent across both survey and vignette methodologies. These negative attitudes may adversely affect the quality of somatic health care provided to this vulnerable population. As discussed previously, research in other populations suggests that negative clinician attitudes can adversely affect clinical decision-making and patient-provider communication13–16 – a finding that the results of the studies by Corrigan et al.,36 Magliano et al.,43 Sullivan et al.,38 and Welch et al.,40 included in this review, suggest holds true for the population with SMI as well.

With individuals with SMI, provider-consumer interactions may be further complicated by factors including cognitive and communication deficits and lack of social support in consumers, discomfort or limited experience treating individuals with SMI among general medical clinicians, and increased likelihood of interactions occurring in emergency room or other non-usual care settings.53 Some of attitudes possibly influenced by these factors, such as perceived dangerousness, are not supported in the literature.54,55 Others, though, may stem from providers’ perceptions that individuals with SMI have lower health literacy56 and smaller social networks57 – perceptions that are supported by evidence and impact individuals’ ability to self-manage health or maintain relationships.58

Interventions to improve clinician attitudes toward stigmatized populations have been effective in other patient groups. Effective interventions have included implicit bias training and mindfulness practices to increase awareness and support modification of negative attitudes, decrease distractions and stressors to reduce cognitive load, and build clinicians’ skills in patient-centered communication.59–61 However, these types of interventions have not yet been adapted to address general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward people with SMI. Educational interventions designed to improve healthcare clinicians’ attitudes about and knowledge of mental illness in general are more common. A Canadian study examined elements of programs implemented to reduce stigma toward mental illness among general medical and mental health clinicians. Two key elements of successful programs were providing a message focused on recovery and including social interactions with individuals successfully living with mental illness, as providers often encounter individuals when they are sickest.62 As indicated in this study, some interventions that are successful in other patient populations (e.g. interactions with individuals in the patient group) may need to be modified to successfully change attitudes about individuals with SMI. One study in this review did include an education intervention aimed at improving attitudes toward individuals with SMI. Uçok et al.35 measured attitudes of general practitioners in Turkey before and after an interactive training session aimed at educating clinicians on schizophrenia, its treatment, the impact of stigma, and their role in the process. Post-test attitudes were more positive for all but two items compared to the pretest. The most change was measured on items related to the course and treatment of schizophrenia.35

Future research is needed in several areas. Only two studies included in this review were conducted in the U.S., and national or other large-scale surveys are needed to comprehensively assess general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI in the U.S. Qualitative research should be conducted to gain in-depth understanding of general medical clinicians’ perceptions of consumers with SMI and their views of the challenges in working with this population. Critically, studies are needed to examine whether and how general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward persons with SMI are associated with clinical care patterns and somatic health outcomes. Finally, interventions for improving clinician attitudes toward individuals with SMI need to be developed and tested for both current general medical clinicians as well as trainees.

There are three main limitations to this study. The included studies were not directly comparable as they measured clinician attitudes in multiple clinician populations and countries, used different measures to assess those attitudes, and reported outcomes in a variety of ways. Additionally, definitions of SMI may have differed across studies as some measured attitudes in response to vignettes that may have described functional impairment while others used only diagnoses and may have been interpreted as with or without functional impairment. Relevant articles may also have been missed during the search process and through exclusion of studies not published in English. An attempt to minimize this risk was made by searching the reference lists of included articles.

Supplementary Material

Implications for Behavioral Health.

The limited available evidence suggests that general medical clinicians inside and outside the U.S. appear to have negative attitudes toward consumers with SMI. Nationally representative surveys of U.S. clinicians are needed to comprehensively characterize general medical clinicians’ attitudes toward consumers with SMI, and future research should examine the relationship between clinicians’ attitudes and delivery of somatic healthcare services for this population. If, as the early research summarized in this review and research in other stigmatized populations suggests, negative attitudes toward people with SMI among general medical clinicians contributes to sub-optimal care delivery for this group, development and evaluation of interventions to modify these attitudes should be conducted.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth M. Stone, Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Lisa Nawei Chen, Division of Psychiatry, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Gail L. Daumit, Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Sarah Linden, Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Emma E. McGinty, Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

References

- 1.Daumit G, Anthony C, Ford DE, et al. Pattern of mortality in a sample of maryland residents with severe mental illness. Psychiatry research. 2010;176(2–3):242–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, Crystal S, Stroup TS. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, Foti ME. Morbidity and Mortality in People with Serious Mental Illness. Alexandria: National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) Medical Directors Council; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence D, Kisely S. Inequalities in healthcare provision for people with severe mental illness. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(4 Suppl):61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newcomer JW, Hennekens CH. Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298:1794–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sajatovic M, Dawson NV. The emerging problem of diabetes in the seriously mentally ill. Psychiatr Danub. 2010;22 Suppl 1:S4–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGinty EE, Baller J, Azrin ST, Juliano-Bult D, Daumit GL. Quality of medical care for persons with serious mental illness: A comprehensive review. Schizophrenia Research. 2015;165(2–3):227–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carney CP, Jones LE. The influence of type and severity of mental illness on receipt of screening mammography. Journal of general internal medicine. 2006;21(10):1097–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, Perlin JB. Mental disorders and quality of diabetes care in the veterans health administration. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1584–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kisely S, Campbell LA, Wang Y. Treatment of ischaemic heart disease and stroke in individuals with psychosis under universal healthcare. The British journal of psychiatry. 2009;195(6):545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daumit GL, McGinty EE, Pronovost P, et al. Patient Safety Events and Harms During Medical and Surgical Hospitalizations for Persons With Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(10):1068–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pescosolido BA, Medina TR, Martin JK, Long JS. The “Backbone” of Stigma: Identifying the Global Core of Public Prejudice Associated With Mental Illness. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(5):853–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):979–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haywood C Jr., Lanzkron S, Bediako S, et al. Perceived discrimination, patient trust, and adherence to medical recommendations among persons with sickle cell disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(12):1657–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabin JA, Riskind RG, Nosek BA. Health Care Providers’ Implicit and Explicit Attitudes Toward Lesbian Women and Gay Men. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):1831–1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zestcott CA, Blair IV, Stone J. Examining the Presence, Consequences, and Reduction of Implicit Bias in Health Care: A Narrative Review. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2016;19(4):528–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. Journal of general internal medicine. 2007;22(9):1231–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit Racial/Ethnic Bias Among Health Care Professionals and Its Influence on Health Care Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e60–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milton AC, Mullan B. Views and experience of communication when receiving a serious mental health diagnosis: satisfaction levels, communication preferences, and acceptability of the SPIKES protocol. J Ment Health. 2017;26(5):395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunningham C, Peters K, Mannix J. Physical health inequities in people with severe mental illness: identifying initiatives for practice change. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2013;34(12):855–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ljungberg A, Denhov A, Topor A. Non-helpful relationships with professionals–a literature review of the perspective of persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Mental Health. 2016;25(3):267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thornicroft G, Rose D, Kassam A. Discrimination in health care against people with mental illness. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(2):113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson C, Noblett J, Parke H, et al. Mental health-related stigma in health care and mental health-care settings. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(6):467–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Long JS, Medina TR, Phelan JC, Link BG. “A Disease Like Any Other”? A Decade of Change in Public Reactions to Schizophrenia, Depression, and Alcohol Dependence. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:1321–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2014;67(12):1291–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Administration SAaMHS. Mental and Substance Use Disorders. https://wwwsamhsagov/disorders 2017;Accessed 1/2/2018.

- 27.Lawrie S, Martin K, McNeill G, et al. General practitioners’ attitudes to psychiatric and medical illness. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28(6):1463–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukherjee R, Fialho A, Wijetunge A, Checinski K, Surgenor T. The stigmatisation of psychiatric illness. The Psychiatrist. 2002;26(5):178–181. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noblett JE, Lawrence R, Smith JG. The attitudes of general hospital doctors toward patients with comorbid mental illness. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2015;50(4):370–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Henderson S. Attitudes towards people with a mental disorder: a survey of the Australian public and health professionals. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;33(1):77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogers TS, Kashima Y. Nurses’ responses to people with schizophrenia. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998;27(1):195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hori H, Richards M, Kawamoto Y, Kunugi H. Attitudes toward schizophrenia in the general population, psychiatric staff, physicians, and psychiatrists: a web-based survey in Japan. Psychiatry research. 2011;186(2):183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishige N, Hayashi N. Occupation and social experience: Factors influencing attitude towards people with schizophrenia. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2005;59(1):89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aydin N, Yigit A, Inandi T, Kirpinar I. Attitudes of hospital staff toward mentally ill patients in a teaching hospital, Turkey. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2003;49(1):17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Üçok A, Soyguer H, Atakli C, et al. The impact of antistigma education on the attitudes of general practitioners regarding schizophrenia. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2006;60(4):439–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corrigan PW, Mittal D, Reaves CM, et al. Mental health stigma and primary health care decisions. Psychiatry research. 2014;218(1):35–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mittal D, Corrigan P, Sherman MD, et al. Healthcare providers’ attitudes toward persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatric rehabilitation journal. 2014;37(4):297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sullivan G, Mittal D, Reaves CM, et al. Influence of schizophrenia diagnosis on providers’ practice decisions. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2015;76(8):1068–1074; quiz 1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith JD, Mittal D, Chekuri L, Han X, Sullivan G. A comparison of provider attitudes toward serious mental illness across different health care disciplines. Stigma and Health. 2017;2(4):327. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Welch LC, Litman HJ, Borba CP, Vincenzi B, Henderson DC. Does a Physician’s Attitude toward a Patient with Mental Illness Affect Clinical Management of Diabetes? Results from a Mixed-Method Study. Health services research. 2015;50(4):998–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lam TP, Lam KF, Lam EWW, Ku YS. Attitudes of primary care physicians towards patients with mental illness in H ong K ong. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry. 2013;5(1):E19–E28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chandramouleeswaran S, Rajaleelan W, Edwin NC, Koshy I. Stigma and attitudes toward patients with psychiatric illness among postgraduate Indian physicians. Indian journal of psychological medicine. 2017;39(6):746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Magliano L, Punzo R, Strino A, Acone R, Affuso G, Read J. General practitioners’ beliefs about people with schizophrenia and whether they should be subject to discriminatory treatment when in medical hospital: The mediating role of dangerousness perception. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2017;87(5):559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Naeem F, Ayub M, Javed Z, Irfan M, Haral F, Kingdon D. Stigma and psychiatric illness. A survey of attitude of medical students and doctors in Lahore, Pakistan. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2006;18(3):46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernando SM, Deane FP, McLeod HJ. Sri Lankan doctors’ and medical undergraduates’ attitudes towards mental illness. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2010;45(7):733–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Björkman T, Angelman T, Jönsson M. Attitudes towards people with mental illness: a cross-sectional study among nursing staff in psychiatric and somatic care. Scandinavian journal of caring sciences. 2008;22(2):170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crisp AH, Gelder MG, Rix S, Meltzer HI, Rowlands OJ. Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;177(1):4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trute B, Tefft B, Segall A. Social rejection of the mentally ill: a replication study of public attitude. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 1989;24(2):69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chicago TNDPftSUo. General Social Survey. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seeman N, Tang S, Brown AD, Ing A. World survey of mental illness stigma. Journal of affective disorders. 2016;190:115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schomerus G, Schwahn C, Holzinger A, et al. Evolution of public attitudes about mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2012;125(6):440–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McGinty EE, Goldman HH, Pescosolido BA, Barry CL. Portraying Mental Illness and Drug Addiction as Treatable Health Conditions: Effects of a Randomized Experiment on Stigma and Discrimination. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;126:73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Druss B Improving medical care for persons with serious mental illness: challenges and solutions. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2007;68:40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morabito MS, Socia KM. Is dangerousness a myth? Injuries and police encounters with people with mental illnesses. Criminology & Public Policy. 2015;14(2):253–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Glied S, Frank RG. Mental illness and violence: Lessons from the evidence. American journal of public health. 2014;104(2):e5–e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clausen W, Watanabe-Galloway S, Baerentzen MB, Britigan DH. Health literacy among people with serious mental illness. Community mental health journal. 2016;52(4):399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cullen BA, Mojtabai R, Bordbar E, Everett A, Nugent KL, Eaton WW. Social network, recovery attitudes and internal stigma among those with serious mental illness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2017;63(5):448–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blixen CE, Kanuch S, Perzynski AT, Thomas C, Dawson NV, Sajatovic M. Barriers to self-management of serious mental illness and diabetes. American journal of health behavior. 2016;40(2):194–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burgess DJ, Beach MC, Saha S. Mindfulness practice: A promising approach to reducing the effects of clinician implicit bias on patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(2):372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. Jama. 2009;302(12):1284–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stone J, Moskowitz GB. Non-conscious bias in medical decision making: what can be done to reduce it? Med Educ. 2011;45(8):768–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Knaak S, Modgill G, Patten SB. Key ingredients of anti-stigma programs for health care providers: a data synthesis of evaluative studies. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;59(1_suppl):19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.