Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Squamous cell esophageal cancer (ESCC) is a highly fatal malignancy. This study aims to investigate the factors affecting survival in patients with metastatic and non-metastatic ESCC.

METHODS:

Between 2008 and 2016, 107 patients with ESCC who were followed up in an oncology clinic were included in the analysis. Patients were grouped based on the stage of disease as clinical-stage II to IV.

RESULTS:

Of the 107 patients, 55 (55.1%) of them were male and 52 (48.6%) of them were female. The mean age was 60.8 years. Based on the clinical-stage, 28 (26.2%) patients had stage II disease, 33 (30.8%) had stage III disease, and 46 (43.0%) had stage IV disease. Twenty-nine (27.1%) patients with the non-metastatic disease underwent surgery following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT), while 29 (27.1%) patients received definitive CRT. Twenty-six (56.5%) patients with metastatic disease received chemotherapy (CT). While median overall survival (mOS) could not be reached in patients who underwent surgery following neoadjuvant CRT, mOS for patients receiving definitive CRT versus patients treated with surgery alone–was 22.0 months and 24.0 months, respectively (p=0.008). In the metastatic stage, mOS was 8.0 months for the patients treated with a first-line CT and 3.0 months for patients receiving best supportive care (p<0.001). In multivariate analysis, factors predicting survival in patients with the non-metastatic disease were ECOG PS 3-4 (Hazard ratio [HR], 6.13), undergoing surgery (HR, 0.22), clinical-stage III disease (HR, 3.19), and presence of recurrence (HR, 24.12). For patients with metastatic disease, ECOG PS 3-4 (HR, 3.31), grade-III histology (HR, 3.39), liver metastasis (HR, 2.53), and receiving CT (HR, 0.15) were the factors associated with survival in multivariate analysis.

CONCLUSION:

In our study, surgery and early clinical-stage increased survival, whereas experiencing recurrence adversely affected survival in non-metastatic ESCC. In the metastatic stage, ECOG PS 3-4, grade-3 histology and liver metastasis adversely affected survival, while receiving CT significantly improved survival.

Keywords: Chemoradiotherapy, chemotherapy, esophageal cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, survival

Esophageal cancer (EC) is a highly fatal malignancy. In the USA, approximately 17,750 people are diagnosed with EC each year, with 16,080 deaths from EC for the same year [1]. Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) account for more than 95% of EC cases [2]. Although the incidence of ESCC in the USA has declined, the incidence of EAC has increased dramatically over the last few years. However, ESCC still remains dominant worldwide [3, 4].

Some risk factors associated with ESCC have been identified in the studies. It is estimated that around 90% of the ESCC cases in the USA are due to smoking, alcohol consumption, and a lower intake of fruits and vegetables. The importance of certain risk factors varies considerably in other parts of the world. In Iran and other Asian countries, the main risk factors for SCC are not well-understood but are thought to be poor nutritional status, low fruit and vegetable intake, and higher temperatures of beverage consumption [5–8].

At the time of diagnosis, 50–80% of the EC patients have locally-advanced or metastatic disease, regardless of histology [6]. While surgery alone may be curative in early stages of the disease, multimodality treatments, including definitive chemoradiotherapy (CRT) and neoadjuvant chemoradiation (NCRT), followed by surgery is recommended for most locally-advanced EC cases. The 5-year survival rate for locally-advanced cases rarely exceeds 30% [9, 10].

Previous studies have reported that stage, Glasgow Prognostic Score, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, serum squamous cell carcinoma antigen and cytokeratin-19 are the important prognostic markers for ESCC [11–15]. This study aims to investigate the factors affecting survival in ESCC patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Medical record of ESCC patients who were followed up and treated at the oncology clinic between 2008 and 2016 were included in this retrospective study. Histological subtypes other than ESCC, patients <18 years of age, patients with multiple malignancies, patients with missing data were excluded from the analysis. A total of 107 eligible patients were included for the analysis in this study.

Data Collection

The following parameters for each patient were collected from the medical records: age, gender, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic ischemic heart disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), smoking status, alcohol consumption, initial symptoms, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS), tumor grade, presence of obstruction, treatments [NACRT, chemotherapy(CT), surgery], treatment regimens [carboplatin-paclitaxel (CP) or cisplatin-5- Fluorouracil (CF)], clinical tumor stage, the site of recurrence or metastasis, and primary tumor localization. The patients were staged according to findings of thoracoabdominal computed tomography and/or PET/CT. NACRT or definitive CRT was given with CF or CP. Radiotherapy was delivered at a total dose of 50.4–66.0 Gy given in 28–35 fractions of 1.8–2.0 Gy per fraction in definitive CRT and total dose of 41.4–50.4 Gy given in 23–28 fractions of 1.8 Gy per fraction in NACRT. Patients were divided into two groups according to ECOG-PS as follows: ECOG-PS 0–2 and ECOG-PS 3–4. Tumor grades were stratified into two groups as follows; grade 1–2 and grade 3. Overall survival (OS) was calculated as the time from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences 22.0 for Windows software (Armonk NY, IBM Corp. 2013) was used for the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics for categorical variables were given as number and percentage. Descriptive statistics for numerical variables were presented as mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum. Chi-square analysis was used to compare the ratios in the groups. Monte Carlo simulation was applied when the conditions were not met. The determinant factors were examined by Cox Regression Analysis. The backward stepwise model was used for p<0.150 values in univariate analysis. Survival analyzes were performed by Kaplan Meier Analysis. The statistical significance level was accepted as p<0.05.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Okmeydani Training and Research Hospital, University of Health Sciences, with the decision number 48670771-514.10.

RESULTS

Of the 107 patients, 55 (55.1%) were male and 52 (48.6%) were female. The mean age was 60.8±12.8 (range, 27–95) years. Thirty-one (29.0%) patients had hypertension, nine (8.4%) patients had diabetes mellitus, six (5.6%) patients had chronic ischemic heart disease, and four (3.7%) patients had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The ECOG PS was 3–4 in seven (6.5%) patients (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient data

| Patients (n=107) % | Stage II-III (n=61) % | Stage IV (n=46) % | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 51.4 | 39.3 | 67.4 | 0.004 |

| Male | 48.6 | 60.7 | 32.6 | |

| Age (years) Mean±SD | 60.8±12.8 | 57.5±12.8 | 64.5±12.0 | 0.008 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| HT | 29.0 | 24.6 | 34.8 | 0.250 |

| DM | 8.4 | 8.2 | 8.7 | 0.927 |

| CIHD | 5.6 | 6.6 | 4.3 | 0.619 |

| CPOD | 3.7 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 0.774 |

| Smoking | 50.5 | 41.0 | 63.0 | 0.024 |

| Alcohol consumption | 3.7 | 0.0 | 8.7 | 0.019 |

| Symptom | ||||

| Dysphagia | 89.7 | 91.8 | 87.0 | 0.525 |

| Abdominal pain | 23.4 | 23.0 | 23.9 | 0.907 |

| Weight loss | 29.0 | 23.0 | 37.0 | 0.114 |

| Presence of obstruction | 49.5 | 36.1 | 67.4 | 0.001 |

| ECOG PS | ||||

| 0–2 | 93.5 | 96.7 | 89.1 | 0.336 |

| 3–4 | 6.5 | 3.3 | 10.9 | |

| Grade | ||||

| I-II | 82.2 | 88.5 | 73.9 | 0.051 |

| III | 17.8 | 11.5 | 26.1 | |

| Clinical-stage | ||||

| II | 26.2 | 45.9 | ||

| III | 30.8 | 54.1 | ||

| IV | 43.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Primary tumor localization | ||||

| Upper 1/3 | 12.1 | 9.8 | 15.2 | 0.120 |

| Middle 1/3 | 57.0 | 65.6 | 45.7 | |

| Lower 1/3 | 30.8 | 24.6 | 39.1 | |

| Treatments | ||||

| Definitive CRT | 27.1 | |||

| CRT followed by surgery | 27.1 | |||

| Surgery alone | 4.9 | |||

| Neoadjuvant CRT regimen | ||||

| CP | 48.3 | 48.3 | ||

| CF | 51.7 | 51.7 | ||

| Definitive CRT regimen | ||||

| CP | 44.8 | 44.8 | ||

| CF | 55.2 | 55.2 | ||

| Surgery | 35.5 | 52.5 | 13.0 | <0.001 |

| Recurrence | ||||

| No | 55.7 | |||

| Local | 8.2 | |||

| Systemic | 36.1 | |||

| The site of metastasis at diagnosis | ||||

| Distant LN | 41.3 | 41.3 | ||

| Liver | 26.1 | 26.1 | ||

| Lung | 30.4 | 30.4 | ||

| Bone | 10.9 | 10.9 | ||

| Peritoneum | 6.5 | 6.5 | ||

| First-line treatment in metastatic setting | ||||

| CT | 53.4 | 48.1 | 56.5 | 0.489 |

| BSC | 46.6 | 51.9 | 43.5 | |

| First-line CT regimen | ||||

| CF | 66.7 | 46.2 | 76.9 | 0.077 |

| CP | 33.3 | 53.8 | 23.1 | |

| Final status | ||||

| Dead | 60.7 | 41.0 | 87.0 | <0.001 |

| Alive | 39.3 | 59.0 | 13.0 |

BSC: Best supportive care; CF: Cisplatin-5-florourasil; CIHD: Chronic ischemic heart disease; COPD: Chronic obstructive lung disease; CP: Carboplatin-paclitaxel; CRT: Chemoradiation; CT: Chemotherapy; ECOG PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; DM: Diabetes mellitus; HT: Hypertension; Max.: Maximum; Min.: Minimum; LN: Lymph node; SD: Standard deviation.

Twenty-eight (26.2%) patients had clinical-stage II disease, 33 (30.8%) patients had stage III disease, and 46 (43.0%) patients had stage IV disease. Primary tumor was localized in upper 1/3 esophagus in 13 (12.1%) patients, middle 1/3 esophagus in 61 (57.0%) patients, and lower 1/3 esophagus in 33 (30.8%) patients. Recurrence developed in 27 (44.3%) patients with clinical-stage II to III disease during the follow-up, with five (8.2%) patients and 22 (36.1%) of them being local recurrence and systemic metastasis, respectively. At the time of diagnosis, the site of metastasis was distant lymph nodes (LN) in 19 (41.3%) patients, liver in 12 (26%) patients, lung in 14 (30.4%) patients, bone in five (10.6%) patients, and peritoneum in three (6.5%) patients (Table 1).

Of the 38 (35.5%) patients who underwent surgery, 32 (78.9%) had curative surgery. NACRT was given to 29 (27.1%) patients, 14 (48.3%) of whom received concurrent carboplatin (AUC2, iv. on day 1) and paclitaxel (50 mg/m2, iv. on day 1) (CP) weekly for five weeks and 15 (51.7%) received concurrent cisplatin (75 mg/m2, on days 1 and 29) and 5-Fluorouracil (iv continuous infusion over 24 hours daily on days 1–4 and 29–33) (CF) 35-day cycle. Definitive CRT was given to 29 (27.1%) patients, 13 (44.8%) of whom received carboplatin (AUC2, iv. on day 1) and paclitaxel (50 mg/m2 iv on day 1) weekly for five weeks and 16 (55.2%) received cisplatin (75 mg/m2 iv on days 1 and 29) and 5-Fluorouracil (1000 mg/m2, iv continuous infusion over 24 hours daily on days 1–4 and 29–33) 35-day cycle. Of the 27 patients with the non-metastatic disease at diagnosis who developed recurrence during follow-up, 13 (48.1) received a first-line CT. Among 46 patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis, 26 (56.5%) received CT. During the median follow up time of 24 months, 65 (60.7%) patients died (Table 1).

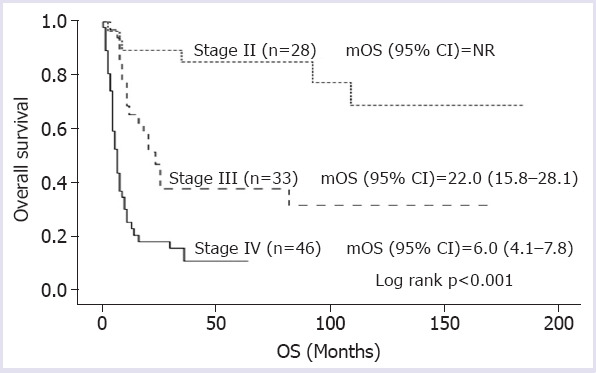

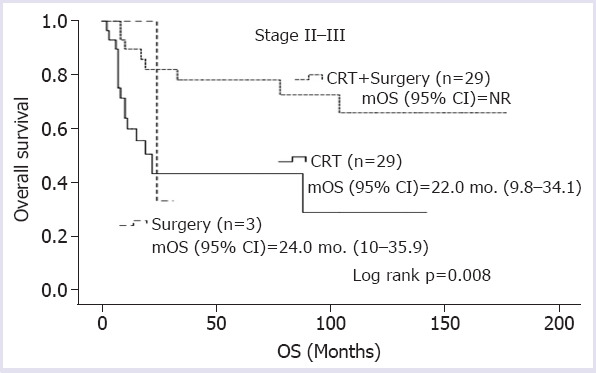

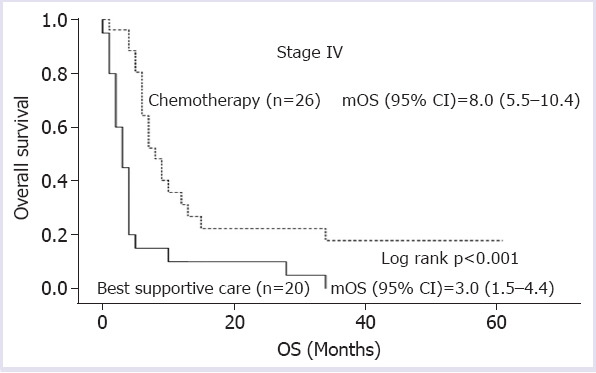

Median overall survival (mOS) was not achieved in clinical-stage II patients, 22.0 (15.8–28.1) months in stage III patients, and 6.0 (4.1–7.8) months in stage IV patients (log rank p<0.001) (Fig. 1). In clinical-stage II-III patients, mOS could not be reached in patients who underwent surgery following neoadjuvant CRT, whereas mOS was only 22.0 months in patients receiving definitive CRT and 24.0 months in those treated with surgery alone (log rank p=0.008) (Fig. 2). In metastatic stage, mOS was 8.0 months for those treated with first-line CT and 3.0 months for patients receiving best supportive care (log rank p<0.001) (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 1.

Overall survival according to the stage at diagnosis.

mOS: Median overall survival; NR: Not reached; OS: Overall survival.

FIGURE 2.

Overall survivals according to the treatment modalities in non-metastatic patients.

mOS: Median overall survival; OS: Overall survival; CRT: Chemoradiation.

FIGURE 3.

Overall survivals according to the treatment modalities in metastatic patients.

mOS: Median overall survival; OS: Overall survival.

In the univariate analysis; presenting with dysphagia (Hazard ratio [HR], 0.26), ECOG PS (HR, 4.50) undergoing surgery (HR, 0.31), presence of obstruction (HR, 3.62), receiving NACRT (HR, 0.28), stage (HR, 4.09), and experiencing recurrence (HR, 7.30) were the factors affecting survival in patients with stage II-III disease (p=0.016, p=0.049, p=0.006, p=0.003, p=0.003, p=0.004, p=0.003, p=0.001, respectively), while gender (HR, 0.43), smoking (HR, 2.50),–ECOG PS (HR, 3.60), liver metastasis (HR, 3.11), lung metastasis (HR, 0.36), and CT (HR, 0.36) were found to be the factors related to survival in patients with stage IV disease (p=0.025, p=0.018, p=0.014, p=0.001, p=0.001, p<0.001, respectively) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Univariate analysis for survival according to the stages

| Stage II-III | Stage IV | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95.0% CI | p | HR | 95.0% CI | p | ||||

| Gender | Female vs. male | 0.584 | 0.264 | 1.290 | 0.184 | 0.430 | 0.206 | 0.898 | 0.025 |

| Age | (year) | 1.027 | 0.993 | 1.062 | 0.117 | 1.000 | 0.974 | 1.026 | 0.986 |

| HT | Yes vs. no | 1.533 | 0.658 | 3.572 | 0.322 | 1.205 | 0.627 | 2.318 | 0.575 |

| DM | Yes vs. no | 1.891 | 0.555 | 6.438 | 0.308 | 1.314 | 0.463 | 3.725 | 0.608 |

| CIHD | Yes vs. no | 2.089 | 0.622 | 7.014 | 0.233 | 1.056 | 0.253 | 4.412 | 0.940 |

| COPD | Yes vs. no | 1.333 | 0.179 | 9.921 | 0.779 | 1.246 | 0.297 | 5.235 | 0.764 |

| Smoking | Yes vs. no | 0.551 | 0.237 | 1.280 | 0.166 | 2.501 | 1.174 | 5.326 | 0.018 |

| Alcohol consumption | Yes vs. no | 0.535 | 0.278 | 1.706 | 0.510 | ||||

| Dysphagia | Yes vs. no | 0.260 | 0.086 | 0.782 | 0.016 | 0.459 | 0.186 | 1.133 | 0.091 |

| Abdominal pain | Yes vs. no | 0.731 | 0.274 | 1.950 | 0.531 | 0.791 | 0.376 | 1.664 | 0.536 |

| Weight loss | Yes vs. no | 0.774 | 0.290 | 2.065 | 0.609 | 0.716 | 0.372 | 1.379 | 0.318 |

| ECOG PS | 3–4 vs. 0–2 | 4.505 | 1.007 | 20.164 | 0.049 | 3.603 | 1.297 | 10.009 | 0.014 |

| Grade | III vs. I-II | 0.216 | 0.029 | 1.620 | 0.136 | 1.918 | 0.949 | 3.879 | 0.070 |

| Surgery | Yes vs. no | 0.317 | 0.139 | 0.724 | 0.006 | 1.457 | 0.606 | 3.501 | 0.400 |

| Obstruction | Yes vs. no | 3.627 | 1.543 | 8.525 | 0.003 | 1.294 | 0.666 | 2.511 | 0.447 |

| Neoadjuvant CRT | Yes vs. no | 0.281 | 0.118 | 0.668 | 0.004 | ||||

| Stage | III vs. II | 4.096 | 1.615 | 10.387 | 0.003 | ||||

| Recurrence | Yes vs. no | 7.301 | 3.027 | 17.609 | 0.001 | ||||

| Distant LN metastasis | Yes vs. no | 1.704 | 1.006 | 2.885 | 0.047 | ||||

| Liver metastasis | Yes vs. no | 3.117 | 1.585 | 6.131 | 0.001 | ||||

| Lung metastasis | Yes vs. no | 0.365 | 0.202 | 0.658 | 0.001 | ||||

| Bone metastasis | Yes vs. no | 0.802 | 0.251 | 2.559 | 0.709 | ||||

| Peritoneum metastasis | Yes vs. no | 1.181 | 0.288 | 4.833 | 0.817 | ||||

| CT vs. BSC | 0.327 | 0.172 | 0.620 | <0.001 | |||||

CI: Confidence interval; HR: Hazard ratio; BSC: Best supportive care; CIHD: Chronic ischemic heart disease; COPD: Chronic obstructive lung disease; CRT: Chemoradiation; CT: Chemotherapy; ECOG PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; DM: Diabetes mellitus; HT: Hypertension; LN: Lymph node.

In multivariate analysis, ECOG PS (HR, 6.13), undergoing surgery (HR, 0.22), stage (HR, 3.19), and experiencing recurrence (HR, 24.12) were the factors associated with survival in patients with stage II-III disease (p=0.028, p=0.002, p=0.031, and p<0.001, respectively), while ECOG PS (HR, 3.31), tumor grade (HR, 3.39), liver metastasis (HR, 2.53), and receiving CT (HR,0.15) were the independent predictors of survival in stage IV patients (p=0.004, p=0.002, p=0.023, and p<0.001, respectively) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Multivariate analysis for survival according to stages

| Stage II-III | Stage IV | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95.0% CI | p | HR | 95.0% CI | p | ||||

| ECOG PS | 3–4 vs. 0–2 | 6.138 | 1.212–31.075 | 0.028 | ECOG PS | 3–4 vs. 0–2 | 3.313 | 1.141–9.693 | 0.004 |

| Surgery | Yes vs. no | 0.229 | 0.092–0.570 | 0.002 | Grade | III vs. I-II | 3.397 | 1.551–7.439 | 0.002 |

| Stage | III vs. II | 3.195 | 1.111–9.183 | 0.031 | Liver metastasis | Yes vs. no | 2.537 | 1.134–5.672 | 0.023 |

| Recurrence | Yes vs. no | 24.128 | 6.455–90.180 | <0.001 | CT vs. BSC | 0.156 | 0.069–0.348 | <0.001 | |

CI: Confidence interval; CT: Chemotherapy; BSC: Best supportive care; ECOG PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; HR: Hazard ratio.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the factors affecting survival in ESCC patients. In non-metastatic disease, undergoing surgery and early stage of the disease increased survival, whereas experiencing recurrence adversely affected survival. In patients with metastatic disease, the presence of ECOG PS 3–4, grade-III histology, and liver metastasis adversely affected survival, whereas CT administration significantly improved survival.

Although the main risk factors for ESCC are not well–understood, it is supposed that malnutrition, low fruit and vegetable consumption, and higher temperatures of food and beverage consumption are the possible risk factors [5]. In areas where ESCC is endemic, disease has no gender specificity. However, ESCC is more common in men in low incidence areas [16]. In our study, more than half of the patients were active smokers; however, smoking status in metastatic stage did not affect survival in multivariate analysis although it was associated with survival in univariate analysis. In our study, only 3.7% patients had a history of alcohol consumption. Interestingly, most of the patients with early stage were male, while the majority of the patients in the metastatic stage were female. The reason for the higher number of female patients with metastatic disease may be due to the delay in diagnosis because of late applications to health institutions.

In ESCC, tumoral obstruction of the esophagus causes progressive dysphagia, often accompanied by weight loss. Dysphagia usually occurs when the esophageal lumen diameter is less than 13 mm and this finding indicates advanced disease [17]. Half of the patients included in the study had obstruction at the time of diagnosis, approximately 90% of the patients had dysphagia, and 29% of the patients had weight loss. The rate of presenting with obstruction at metastatic stage was significantly higher. Three-fourths of patients in the study had locally-advanced or metastatic disease.

RTOG 85–01 study by Al Sarraf et al. [18] included 123 patients with ESCC or EAC and compared RT to definitive CRT in locally-advanced stage. Sixty-two patients received RT alone and 61 patients received definitive CRT with CF. The mOS in the definitive CRT arm was 14.1 months compared to 9.3 months in the RT alone arm. Later, 69 patients were treated with combined modality approach and the results were reported to be similar to the previous findings, with mOS being 17.2 months. In a study by Stahl et al. [19], 172 patients with locally-advanced EC were randomized to three cycles of induction CT followed by NACRT and surgery arm or definitive CRT arm. There was no significant difference in mOS between the two groups after a 6-year of follow-up time. The 2-year locoregional control rate was better in patients undergoing surgery. In the metaanalyzes evaluating NACRT studies in EC, NACRT has been shown to provide better results compared to surgery alone [20–22]. In a meta-analysis by Jin et al. [20], which evaluated 14 randomized trials comparing NACRT to surgery alone, local control rates and survival rates were reported to be better with NACRT than surgery alone. Similarly, in meta-analysis conducted by Urschel et al. [21], which included nine randomized trials comparing NACRT to surgery alone, both 3-year survival and local control rate were found to be better in the NACRT arm.

In our study, 29 patients were treated with definitive CRT and had mOS of 22 months. In our study, there were no patients who received RT alone, whereas 29 patients underwent surgery following NACRT and mOS could not be reached. Only three patients were treated with surgery alone and had mOS of 24 months. In our study, no adjuvant treatment was administered. In multivariate analysis, undergoing surgery significantly improved survival. Of 29 patients treated with definitive CRT, 14 (49.3%) had recurrence, with 3 (10.3) of them experiencing local recurrence. Of 29 patients who underwent surgery following NACRT, 10 (34.5%) had recurrence, with only one (3.4%) of them experiencing local recurrence. All patients (n=3) who treated with surgery alone developed recurrence, with one (33.3%) of them having local recurrence.

Javle et al. [23] included 172 EC patients in their analysis, 74 of whom were ESCC. In the study, stage and surgery were found to be independent factors affecting survival. Similarly, Kumagai et al. [24] found that stage was the independent factor associated with survival in ESCC patients treated with surgery. In our study, clinical-stage and ECOG PS in non-metastatic stage were the factors related to survival. In addition, experiencing recurrence increased the mortality by 24-fold. In non-metastatic disease, undergoing surgery following NACRT decreased mortality by 80%.

It has been shown CT administration in metastatic EC patients prolongs survival and reduces symptoms [25, 26]. Likewise, it was shown in our study that receiving CT significantly prolonged survival in patients with metastatic disease. In addition, grade 3 histology, liver metastasis, and ECOG PS adversely affected survival in metastatic stage.

The strengths of our study were that this study included only ESCC patients and analyzed metastatic and non-metastatic patients separately. Moreover, median follow-up time was relatively longer. However, its retrospective nature, single-center design, and small sample size were the limitations of the present study.

In conclusion, undergoing surgery, ECOG-PS, stage, and experiencing recurrence were the significant factors associated with survival in patients with the non-metastatic disease, while grade, ECOG PS, liver metastasis, and receiving CT were the independent predictors of survival in patients with metastatic disease.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Okmeydani Training and Research Hospital, University of Health Sciences, with the decision number 48670771-514.10 (date: 02.08.2019)

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

Authorship Contributions: Concept – AS, SC, SS; Design – NY, CG, SS; Supervision – SC, SS, CD, AS; Resources – CG, SC, SA, MMA; Materials – AS, NY, SA, CG; Data collection and/or processing – AS, NY, YYU, CD; Analysis and/or interpretation – SC, YYU, MMA, AS; Literature review – CD, AS, YYU, SS; Writing – AS, MMA, YYU, SS; Critical review – SC, CD, MMA, YYU; Other – CG, YYU, SC, NY.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thrift AP. The epidemic of oesophageal carcinoma:Where are we now? Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;41:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pohl H, Sirovich B, Welch HG. Esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence:are we reaching the peak? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1468–70. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baquet CR, Commiskey P, Mack K, Meltzer S, Mishra SI. Esophageal cancer epidemiology in blacks and whites:racial and gender disparities in incidence, mortality, survival rates and histology. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:1471–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engel LS, Chow WH, Vaughan TL, Gammon MD, Risch HA, Stanford JL, et al. Population attributable risks of esophageal and gastric cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1404–13. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dandara C, Robertson B, Dzobo K, Moodley L, Parker MI. Patient and tumour characteristics as prognostic markers for oesophageal cancer:a retrospective analysis of a cohort of patients at Groote Schuur Hospital. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49:629–34. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezv135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He Z, Zhao Y, Guo C, Liu Y, Sun M, Liu F, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for esophageal squamous cell cancer and precursor lesions in Anyang, China:a population-based endoscopic survey. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1085–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Randi G, Scotti L, Bosetti C, Talamini R, Negri E, Levi F, et al. Pipe smoking and cancers of the upper digestive tract. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2049–51. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, Steyerberg EW, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BP, et al. CROSS Group. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2074–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suntharalingam M, Moughan J, Coia LR, Krasna MJ, Kachnic L, Haller DG, et al. 1996-1999 Patterns of Care Study. The national practice for patients receiving radiation therapy for carcinoma of the esophagus:results of the 1996-1999 Patterns of Care Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:981–7. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00256-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuchiya Y, Onda M, Miyashita M, Sasajima K. Serum level of cytokeratin 19 fragment (CYFRA 21-1) indicates tumour stage and prognosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus. Med Oncol. 1999;16:31–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02787356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nabeya Y, Shimada H, Okazumi S, Matsubara H, Gunji Y, Suzuki T, et al. Serum cross-linked carboxyterminal telopeptide of type I collagen (ICTP) as a prognostic tumor marker in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:940–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duan H, Zhang X, Wang FX, Cai MY, Ma GW, Yang H, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in operable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5591–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i18.5591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun P, Zhang F, Chen C, An X, Li YH, Wang FH, et al. Comparison of the prognostic values of various nutritional parameters in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma from Southern China. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5:484–91. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.08.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirahara N, Matsubara T, Hayashi H, Takai K, Fujii Y, Tajima Y. Impact of inflammation-based prognostic score on survival after curative thoracoscopic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:1308–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pottern LM, Morris LE, Blot WJ, Ziegler RG, Fraumeni JF., Jr Esophageal cancer among black men in Washington, D.C. I. Alcohol, tobacco, and other risk factors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981;67:777–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cavallin F, Scarpa M, Cagol M, Alfieri R, Ruol A, Sileni VC, et al. Esophageal Cancer Clinical Presentation:Trends in the Last 3 Decades in a Large Italian Series. Ann Surg. 2018;267:99–104. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.al-Sarraf M, Martz K, Herskovic A, Leichman L, Brindle JS, Vaitkevicius VK, et al. Progress report of combined chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in patients with esophageal cancer:an intergroup study. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:277–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stahl M, Stuschke M, Lehmann N, Meyer HJ, Walz MK, Seeber S, et al. Chemoradiation with and without surgery in patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2310–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lv J, Cao XF, Zhu B, Ji L, Tao L, Wang DD. Effect of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy on prognosis and surgery for esophageal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4962–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urschel JD, Vasan H, Blewett CJ. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials that compared neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery to surgery alone for resectable esophageal cancer. Am J Surg. 2002;183:274–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00795-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gebski V, Burmeister B, Smithers BM, Foo K, Zalcberg J, Simes J Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group. Survival benefits from neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy in oesophageal carcinoma:a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:226–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Javle MM, Nwogu CE, Donohue KA, Iyer RV, Brady WE, Khemka SV, et al. Management of locoregional stage esophageal cancer:a single center experience. Dis Esophagus. 2006;19:78–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumagai Y, Nagata K, Ishiguro T, Haga N, Kuwabara K, Sobajima J, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and clinical outcomes of esophageal basaloid squamous carcinoma:experience at a single institution. Int Surg. 2013;98:450–4. doi: 10.9738/CC195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ford HE, Marshall A, Bridgewater JA, Janowitz T, Coxon FY, Wadsley J, et al. COUGAR-02 Investigators. Docetaxel versus active symptom control for refractory oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma (COUGAR-02):an open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:78–86. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70549-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janmaat VT, Steyerberg EW, van der Gaast A, Mathijssen RH, Bruno MJ, Peppelenbosch MP, et al. Palliative chemotherapy and targeted therapies for esophageal and gastroesophageal junction cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11:CD004063. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004063.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]