Dear Editor,

While the world is in lockdown for months since December of 2019 due to novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, a lot of research is in progress to find out various risk factors associated with COVID-19 progression and related mortalities.1

We read with great interest, the recent and very informative article by Zheng et al.,2 who performed a meta-analysis to identify various risk factors such as; demographical (male, age, current smoking), comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, malignancy, respiratory disease and cardiovascular disease), and other laboratory variables for the progression of COVID-19.

Firstly, we have a concern related to the result on the presence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in association with COVID-19. The reported result for this pooled-outcome based on ten included studies has been shown to be statistically significant with a higher proportion of CVD in critical/mortal group compared to the non-critical group of COVID-19 patients. The pooled effect size for this association has been reported as odds ratio (OR) with its 95% confidence interval (CI) levels (OR=5.19, 95% CI=3.25–8.29, P<0.00001). However, upon proper examination of the reported forest plot and the included studies, we observed that the input data for one included study by Shi Y et al.,3 was wrong and therefore the outcome ‘effect size’ for this study has been shown to be ‘Not Estimable’ (Fig. 3. of Zheng et al.).2

It is very much important for proper data inputs and thorough checks for its correctness by multiple authors while performing ameta-analysis. In the reported meta-analysis, the CVD events and total number under critical/mortal group from a study by Shi Y et al.,3 have been recorded for meta-analysis as 49 and 4, respectively. It is for this reason, the effect-size has been found to be ‘Not Estimable’ in the respective forest plot (Fig. 3. of Zheng et al.).2 We, upon a thorough review of the study by Shi Y et al., noticed that the actual values are 4 and 49 for CVD events and total number, respectively.3

Secondly, by further inspecting the forest plot, in addition to inappropriate data inputs, the study weights have been noticed to be very disproportionate to each other (minimum 1.7 & maximum 28.7).2 It is a known myth to choose either fixed or random effects model for a meta-analysis based on the heterogeneity statistics, particularly fixed effects model is not a viable method when objective is to measure the effect size of group level variables.4

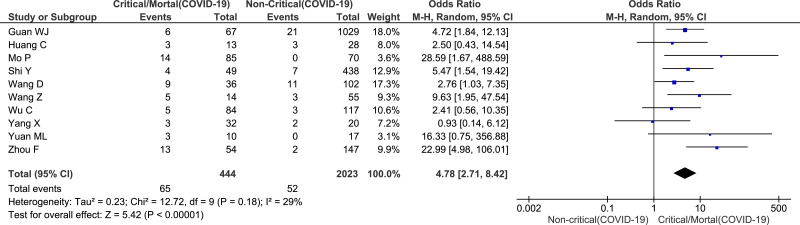

Therefore, in this letter we updated the forest plot and the effect-size characteristics for the relationship between CVD and COVID-19 progression (including the missing data for a study & random effects model which considers both within and between study variability). According to the random effects model used (Fig. 1 ), the study weights were found to better distributed than in the fixed effects model (minimum 3.1 & maximum 18.0), and the results showed a significantly higher proportion of CVD in critical/mortal group compared to the non-critical group of COVID-19 patients (OR=4.78, 95% CI=2.71–8.42, P<0.00001). Considering the limitation that the COVID-19 patients with underlying CVD may also have other comorbidities, the use of random effects model would provide a better statistic and the obtained result should be interpreted with a caution to the limitation of other overlapping comorbidities.

Fig. 1.

Forest plot for cardiovascular disease comorbidity between critical/mortal and non-critical COVID-19 patients.

References

- 1.Chan J.F., Yuan S., Kok K.H. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster.[J] Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–523. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30154-9. doi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng Z., Peng F., Xu B. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 23] J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021. S0163-4453(20)30234-6doi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi Y., Yu X., Zhao H. Host susceptibility to severe COVID-19 and estab- lishment of a host risk score: findings of 487 cases outside Wuhan.[J] Crit Care. 2020;24(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2833-7. doi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dieleman J.L., Templin T. Random-effects, fixed-effects and the within-between specification for clustered data in observational health studies: a simulation study.[J] PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110257. doi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]