Key Points

Question

What are the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of viltolarsen in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) amenable to exon 53 skipping?

Findings

Results of this 4-week randomized clinical trial for safety followed by a 20-week open-label treatment period in 16 patients with DMD indicated significant drug-induced dystrophin production in both viltolarsen groups (40 mg/kg per week and 80 mg/kg week) after 20 to 24 weeks of treatment. Timed function tests provided supportive evidence of treatment-related clinical improvement, and viltolarsen was well tolerated.

Meaning

Viltolarsen may provide a new therapeutic option for patients with DMD amenable to exon 53 skipping.

This phase 2 randomized clinical trial evaluates the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of viltolarsen in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy amenable to exon 53 skipping

Abstract

Importance

An unmet need remains for safe and efficacious treatments for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). To date, there are limited agents available that address the underlying cause of the disease.

Objective

To evaluate the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of viltolarsen, a novel antisense oligonucleotide, in participants with DMD amenable to exon 53 skipping.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This phase 2 study was a 4-week randomized clinical trial for safety followed by a 20-week open-label treatment period of patients aged 4 to 9 years with DMD amenable to exon 53 skipping. To enroll 16 participants, with 8 participants in each of the 2 dose cohorts, 17 participants were screened. Study enrollment occurred between December 16, 2016, and August 17, 2017, at sites in the US and Canada. Data were collected from December 2016 to February 2018, and data were analyzed from April 2018 to May 2019.

Interventions

Participants received 40 mg/kg (low dose) or 80 mg/kg (high dose) of viltolarsen administered by weekly intravenous infusion.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcomes of the trial included safety, tolerability, and de novo dystrophin protein production measured by Western blot in participants’ biceps muscles. Secondary outcomes included additional assessments of dystrophin mRNA and protein production as well as clinical muscle strength and function.

Results

Of the 16 included boys with DMD, 15 (94%) were white, and the mean (SD) age was 7.4 (1.8) years. After 20 to 24 weeks of treatment, significant drug-induced dystrophin production was seen in both viltolarsen dose cohorts (40 mg/kg per week: mean [range] 5.7% [3.2-10.3] of normal; 80 mg/kg per week: mean [range] 5.9% [1.1-14.4] of normal). Viltolarsen was well tolerated; no treatment-emergent adverse events required dose reduction, interruption, or discontinuation of the study drug. No serious adverse events or deaths occurred during the study. Compared with 65 age-matched and treatment-matched natural history controls, all 16 participants treated with viltolarsen showed significant improvements in timed function tests from baseline, including time to stand from supine (viltolarsen: −0.19 s; control: 0.66 s), time to run/walk 10 m (viltolarsen: 0.23 m/s; control: −0.04 m/s), and 6-minute walk test (viltolarsen: 28.9 m; control: −65.3 m) at the week 25 visit.

Conclusions and Relevance

Systemic treatment of participants with DMD with viltolarsen induced de novo dystrophin production, and clinical improvement of timed function tests was observed.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02740972

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is an X-linked disorder affecting approximately 1 in 3500 to 5000 live male births.1,2,3 Progressive weakness and skeletal muscle degeneration are caused by an absence of functional dystrophin protein secondary to loss-of-function variants in the DMD gene.1,4 Patients with DMD typically exhibit dystrophin levels less than 3% of normal.5 Dystrophin deficiency in DMD leads to progressive disability and early death owing to respiratory failure and cardiac dysfunction.1,6 Patients with Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) exhibit in-frame deletions in DMD that allow for production of partially functional truncated dystrophin, with later onset, decreased severity, and slower disease progression compared with patients with DMD.7

Current therapeutic options for DMD are mainly prescribed for symptom management.6,8 Exon skipping therapy offers the potential to partially restore the levels of functional dystrophin.9 The approach uses antisense oligonucleotides to alter RNA splicing by forcing the exclusion of an exon neighboring the DMD variant.9 This converts a DMD out-of-frame variant to a BMD-like in-frame deletion, resulting in production of truncated dystrophin protein, similar to patients with BMD.7,9

Viltolarsen, a phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer drug, was developed to treat patients who have DMD variants amenable to exon 53 skipping.10 Exon 53 skipping is applicable in approximately 8% to 10% of patients, including those with deletions in exons 45-52, 47-52, 48-52, 49-52, 50-52, and 52.4,11 In preclinical studies, viltolarsen has been shown to strongly promote dose-dependent exon 53 skipping during pre-mRNA splicing and increase dystrophin protein levels.10,11

Recent studies reported the efficacy and safety of viltolarsen in ambulatory and nonambulatory patients with DMD.10 Here, we report findings from a phase 2, 24-week randomized clinical trial designed to evaluate efficacy, safety, and tolerability of 2 dosing strengths of viltolarsen in boys with DMD aged 4 to 9 years.

Methods

Trial Oversight

The trial protocol was approved by ethics review panels of each participating recruitment center and can be found in Supplement 1. Prior to any study-related procedures, the participant provided written or verbal informed assent appropriate for age and developmental status and the participants’ parent or legal guardian provided written informed consent and/or HIPAA authorization. The trial was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice regulations. Activities were overseen by an independent data and safety monitoring board.

Participants

Participants were recruited from 6 sites in North America (5 in the US and 1 in Canada). Eligible participants were boys aged 4 to 9 years with a confirmed diagnosis of DMD amenable to exon 53 skipping. Participants had normal findings on clinical safety laboratory tests (allowing for findings of DMD), were ambulatory, and could complete time to stand from supine, time to run/walk 10 m, and time to climb 4 stairs assessments at screening. Participants were taking a stable dose of glucocorticoids for 3 months or more prior to enrollment and for the duration of the study. Participants were excluded if they met any of the following criteria at screening: acute illness as determined by the site investigator (generally upper respiratory tract infection, gastroenteritis, or any febrile illness) 4 weeks prior to first dose, evidence of symptomatic cardiomyopathy, severe allergy or hypersensitivity to study drug, severe behavioral or cognitive problems, any medical findings that would make participation unsafe or impair the assessment of study results or the conduct of the study according to investigator opinion, taking any other investigational drug currently or in the previous 3 months, surgery in the previous 3 months or planned during the study, previous participation in a study that included viltolarsen administration, or positive test results for hepatitis B antigen, hepatitis C antibody, or HIV antibody. An external comparator group for timed function and strength evaluations was provided by the Cooperative International Neuromuscular Research Group (CINRG) Duchenne Natural History Study (DNHS) and was matched for key enrollment criteria, including age, functional status, geographic location, and glucocorticoid treatment status.12,13

Trial Design

This phase 2, multicenter, 2-period, dose-finding randomized clinical trial of low-dose (40 mg/kg per week) and high-dose (80 mg/kg per week) viltolarsen was conducted in participants with DMD amenable to exon 53 skipping with 8 participants in each dose cohort. The low-dose viltolarsen cohort was fully enrolled prior to enrollment in the high-dose viltolarsen cohort; participants and study teams were informed regarding the dose cohort. In both cohorts, participant screening, clinical assessments, and a baseline skeletal muscle biopsy were performed before the first administration of the study drug (eFigure in Supplement 2).

The first study period, which corresponded to the first 4 weeks of treatment following enrollment, was double-blinded and placebo-controlled. Participants in both dose cohorts were randomized 3:1 to receive viltolarsen or placebo. Randomization was based on permuted blocks generated by an unblinded statistician and maintained by Xerimis. In the low-dose cohort, a minimum of 1 week was required between the initial dosing of each of the first 4 participants to monitor for safety. After the fourth participant received the initial dose, the remaining participants could receive treatment. After completion of the first 4 weeks for all participants in the low-dose cohort, safety results were assessed by the study chair, medical monitor, data and safety monitoring board, and sponsor before initiating randomization in the high-dose cohort. The same 1-week latency between initial dosing of each of the first 4 participants was followed for the high-dose cohort, except the second participant in this cohort failed screening so there was no 1-week delay in dosing between participants 3 and 4.

The second study period began at week 5 for each participant. During this period, all participants received viltolarsen according to their cohort dose for a 20-week open-label treatment period. Treatment was administered by hour-long intravenous infusions once a week for the duration of the study. The study drug was packaged, labeled, and distributed to study sites by Xerimis. Following completion of the 24-week treatment period, each participant had a posttreatment skeletal muscle biopsy performed and was eligible for an open-label extension study.14

Muscle Biopsy

To analyze dystrophin induction, biopsies were taken from a biceps muscle at baseline and the other biceps muscle after 24 weeks of treatment. Muscle samples were snap frozen and delivered to a central laboratory. All laboratory researchers remained blinded to sample identity. Dystrophin induction was assessed by Western blot, reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), mass spectrometry (MS), and immunofluorescence (IF) staining using methods recently described (eMethods in Supplement 2).2

Outcomes

Primary study outcomes included safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics (to be reported separately) of low-dose (40 mg/kg per week) and high-dose (80 mg/kg per week) viltolarsen in ambulant boys with DMD. Safety was evaluated in participants receiving 1 dose or more of viltolarsen by the occurrence of adverse events (AEs), serious AEs, laboratory parameters, vital signs, and physical examination results at study visits or participant contact as determined by study protocol. Treatment-emergent AEs were coded by system organ class and preferred term according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities. Severity was assigned according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grading. Muscle dystrophin production was assessed as protein production by Western blot for the primary study efficacy outcome and as dystrophin mRNA splicing on RT-PCR, dystrophin protein production by MS, and dystrophin localization by IF staining for secondary study efficacy outcomes.

Additional secondary efficacy outcomes were gross motor skill assessments of timed function tests, including time to stand from supine, time to run/walk 10 m, time to climb 4 stairs, North Star Ambulatory Assessment, and 6-minute walk test as well as quantitative muscle testing. These outcomes were compared with a matched natural history control group from the CINRG DNHS.13

Statistical Analysis

Sample size considerations were taken for both categorical outcomes (eg, AEs) and continuous variables (eg, percentage of normal dystrophin and safety laboratory variables). The sample size was calculated to be large enough to observe 1 or more AEs with an underlying rate of 10% or greater with more than 80% probability. For continuous variables, there was an 80% probability of detection of any difference of 2.1 SDs or more and 90% power to detect differences of 2.4 SDs or more between the combined placebo and any dose groups while controlling for 2-sided type I error of .05. Comparison of combined treatment groups and combined placebo groups in the study had an 80% power to detect differences of 1.75 SDs and 90% power to detect differences of 2.0 SDs.

Safety and exposure evaluations included all randomized participants who received 1 or more doses of investigational product. Efficacy evaluations were performed in randomized participants who received 1 or more doses of the investigational product, had a baseline assessment, and had 1 or more postbaseline efficacy assessments.

All 16 randomized participants were included in safety and efficacy analysis sets. All statistical tests were performed at a significance level of .05 without correction for multiple comparisons or multiple outcomes. Statistically significant changes in percentage of normal dystrophin production within dose groups and with both dose groups combined, as measured by Western blot, MS, IF staining, and RT-PCR, were assessed using 2-sided t tests. Analysis of timed function tests and muscle strength within the study population was performed by 2-sided paired t tests. Comparisons of the study population and the CINRG DNHS population were performed using a mixed-effects linear model. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Participants

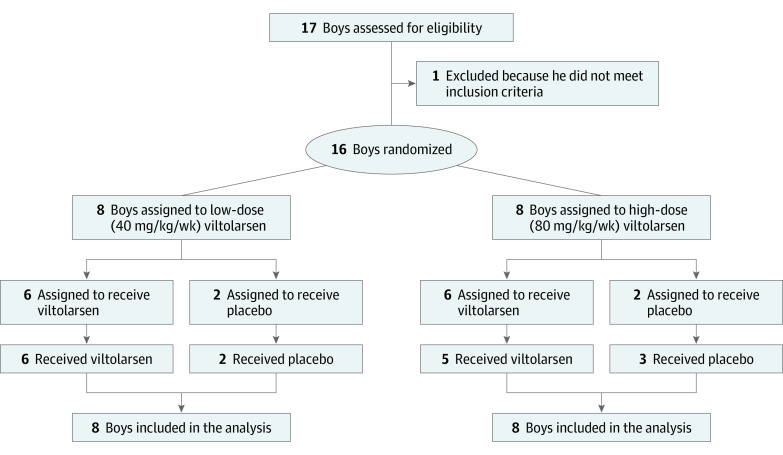

Between December 2016 and August 2017, 16 participants were enrolled in the study (Figure 1). Of the 16 included boys with DMD, 15 (94%) were white, and the mean (SD) age was 7.4 (1.8) years. Eight participants were randomized to each dose cohort (low-dose [40 mg/kg per week] and high-dose [80 mg/kg per week] viltolarsen groups) during the initial 4-week study period: 6 participants to viltolarsen and 2 to matching placebo. However, due to a randomization error in the high-dose cohort, 5 participants received high-dose viltolarsen and 3 participants received placebo. During the 20-week open-label treatment period, all participants received viltolarsen according to their cohort dose (eFigure in Supplement 2). All 16 randomized participants completed treatment. Overall, the participants in the 2 dose groups were balanced with respect to baseline characteristics (Table 1). All participants had deletions encompassing multiple exons that were amenable to exon 53 skipping (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

Participant flow throughout the trial.

Table 1. Demographic and Baseline Clinical Characteristicsa.

| Baseline characteristic | Viltolarsen cohort, mean (SD) | CINRG DNHS control cohort, mean (SD) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-wk Double-blinded placebo-controlled period | 20-wk Open-label treatment period | Total (n = 16) | ||||||

| Placebo (n = 5) | Low-dose group (n = 6) | High-dose group (n = 5) | Low-dose group (n = 8) | High-dose group (n = 8) | Exon 53 amenable controls (n = 9) | All controls (n = 65) | ||

| Age, y | 7.4 (2.1) | 7.4 (1.8) | 7.3 (2.1) | 7.5 (1.8) | 7.2 (2.0) | 7.4 (1.8) | 6.3 (1.1) | 7.1 (1.4) |

| Race, No. (%) | ||||||||

| White | 5 (100) | 6 (100) | 4 (80) | 8 (100) | 7 (88) | 15 (94) | 7 (78) | 55 (85) |

| Black/African American | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Asian | 0 | 0 | 1 (20) | 0 | 1 (13) | 1 (6) | 1 (11) | 4 (6) |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (11) | 5 (8) |

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 0 | 0 | 1 (20) | 0 | 1 (13) | 1 (6) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 4 (80) | 6 (100) | 4 (80) | 8 (100) | 6 (75) | 14 (88) | 9 (100) | 64 (99) |

| Not reported | 1 (20) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (13) | 1 (6) | 0 | 0 |

| Weight, kg | 23.2 (2.0) | 23.5 (5.5) | 22.2 (8.0) | 23.7 (4.7) | 22.3 (6.2) | 23.0 (5.3) | 21.6 (4.0) | 24.0 (6.0) |

| Height, cm | 114.0 (6.4) | 115.4 (7.3) | 110.3 (11.3) | 114.6 (6.5) | 112.2 (10.0) | 113.4 (8.2) | 111.3 (7.6) | 116.2 (10.0) |

| BMIb | 17.9 (1.4) | 17.4 (2.5) | 17.7 (2.6) | 17.9 (2.3) | 17.4 (2.0) | 17.7 (2.1) | 17.3 (2.0) | 17.5 (2.3) |

| Timed-function testsc | ||||||||

| Time to run/walk 10 m velocity, m/s | NA | NA | NA | 1.67 (0.39) | 1.88 (0.36) | 1.77 (0.37) | 1.92 (0.46) | 1.91 (0.47) |

| Time to run/walk 10 m, s | NA | NA | NA | 6.30 (1.59) | 5.55 (1.34) | 5.93 (1.47) | 5.45 (1.17) | 5.61 (1.67) |

| Time to stand from supine velocity, rise/s | NA | NA | NA | 0.26 (0.06) | 0.25 (0.09) | 0.25 (0.07) | 0.23 (0.07) | 0.22 (0.09) |

| Time to stand from supine, s | NA | NA | NA | 4.17 (1.15) | 4.76 (2.58) | 4.44 (1.96) | 4.61 (1.42) | 5.55 (3.04) |

| 6-Minute walk test, m | NA | NA | NA | 391.4 (33.3) | 353.4 (106.3) | 372.4 (78.6) | 428.4 (63.5) | 408.0 (167.2) |

| Time to climb 4 stairs velocity, m/s | NA | NA | NA | 0.27 (0.08) | 0.32 (0.08) | 0.30 (0.08) | 0.30 (0.08) | 0.28 (0.11) |

| Time to climb 4 stairs, s | NA | NA | NA | 3.90 (0.93) | 3.33 (0.94) | 3.61 (0.95) | 4.05 (1.52) | 4.30 (1.87) |

| NSAA score | NA | NA | NA | 24.8 (5.9) | 23.8 (5.1) | 24.3 (5.4) | 28.0 (6.7)d | 25.7 (5.4)e |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CINRG, Cooperative International Neuromuscular Research Group; DNHS, Duchenne Natural History Study; NA, not applicable; NSAA, North Star Ambulatory Assessment.

The low-dose cohort received 40 mg/kg per week of viltolarsen; the high-dose cohort received 80 mg/kg per week.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Baseline timed function tests were reported by dose cohort.

n = 4.

n = 22.

Regarding overall baseline characteristics, 65 participants in the external comparator group, whose data were drawn from the CINRG DNHS, were matched to viltolarsen-treated participants (Table 1). The CINRG DNHS group included 9 patients with DMD amenable to exon 53 skipping and 56 with DMD with non–exon 53 skipping deletion variants (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

Efficacy Outcomes

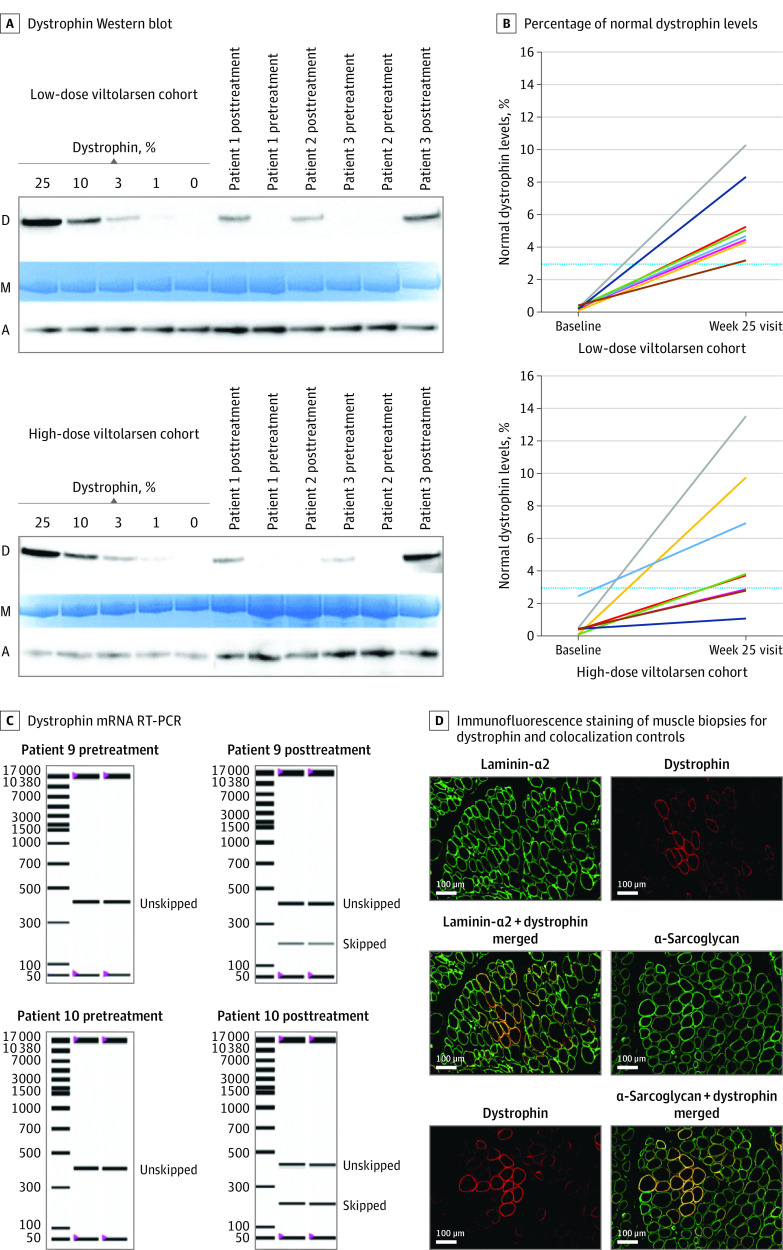

Baseline muscle biopsies showed undetectable or low levels of dystrophin by Western blot in both dose groups, consistent with DMD diagnosis (Figure 2A). When dystrophin was normalized to myosin heavy chain, the low-dose and high-dose viltolarsen cohorts exhibited a mean (SD) percentage of normal dystrophin levels of 0.3% (0.1%) and 0.6% (0.8%), respectively (Figure 2B) (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). All participants showed significant increases in dystrophin content in their week 25 posttreatment biopsies as measured by Western blot. Participants exhibited a mean (SD) percentage of normal dystrophin levels of 5.7% (2.4%) in the low-dose cohort and 5.9% (4.5%) in the high-dose cohort. Similar results were also reported when dystrophin protein levels were normalized to α-actinin (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). A significant difference between baseline and posttreatment biopsies was observed in both treatment groups (low-dose viltolarsen cohort: change from baseline normalized to myosin heavy chain, 5.4%; P < .001; high-dose viltolarsen cohort: change from baseline normalized to myosin heavy chain, 5.3%; P = .01).

Figure 2. Evaluation of Dystrophin Induction.

Muscle biopsies randomized and tested by blinded analysts. A, Dystrophin Western blot. Examples of participants with Duchenne muscular dystrophy treated with 40 mg/kg per week (low-dose cohort) and 80 mg/kg per week (high-dose cohort) of viltolarsen are shown, together with standard curve for dystrophin (D) quantitation. The lanes indicate individual participants; samples were pretreatment (baseline) and posttreatment (week 25 visit) biopsies. Normalization was to both myosin heavy chains (M) and α-actinin (A). All biopsies were analyzed with triplicate gels. B, Percentage of normal dystrophin levels was graphed for each participant at baseline and posttreatment at the week 25 visit. Dystrophin was measured using Western blot and normalized to myosin heavy chains. The blue line denotes 3% of normal dystrophin levels. Each line indicates a different patient. C, Dystrophin mRNA reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Examples of pretreatment and posttreatment biopsies from the high-dose group are shown, each tested in duplicate assays. D, Immunofluorescence staining of muscle biopsies for dystrophin and colocalization controls. Serial cryosections were double stained with dystrophin and laminin α2 or dystrophin and α-sarcoglycan from a participant who received 80 mg/kg per week of viltolarsen.

Secondary outcomes included assessment of muscle dystrophin mRNA and protein production by MS and IF localization. In both dose groups, pretreatment muscle biopsies showed 100% of mRNA transcripts to be out of frame. In posttreatment biopsies, all participants showed viltolarsen-induced exon 53 skipping, leading to a high proportion of in-frame mRNA transcripts (Figure 2C) (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). There was a significant dose effect comparing posttreatment exon skipping between the low-dose and high-dose groups. Using MS, the differences from baseline for the low-dose and high-dose groups and the total group were all significant; however, no significant differences were observed between groups. Viltolarsen-induced dystrophin was seen by IF staining, with significant increases in the percentage of dystrophin-positive myofibers in the posttreatment biopsies in both dose groups (Figure 2D) (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). A significant dose effect was seen between the low-dose and high-dose groups.

Comparison of measures of dystrophin induction demonstrated agreement among the 4 measures of assessment (Western blot, RT-PCR, MS, and IF staining). Participants who exhibited the highest levels of dystrophin by Western blot also generally showed the highest levels of RNA skipping, dystrophin by MS, and percentage of dystrophin-positive myofibers by IF staining.

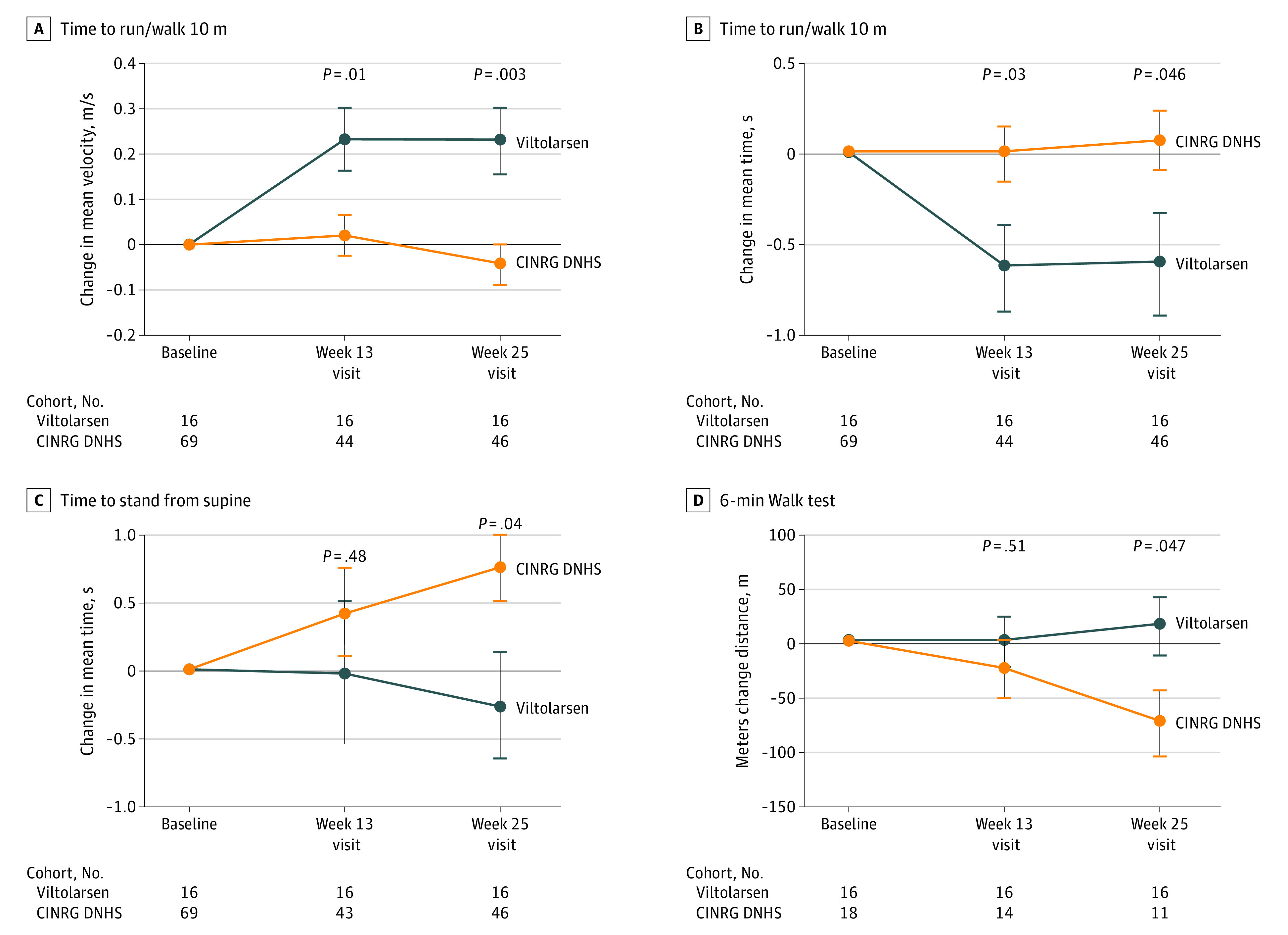

Disease progression was measured using timed function tests and muscle strength assessments. Comparison of viltolarsen-treated participants with 65 age-matched and treatment-matched natural history controls from CINRG DNHS demonstrated evidence of clinical benefit of viltolarsen treatment (Figure 3). Viltolarsen-treated participants showed improvement or stabilization of function over the 25-week period, whereas the CINRG DNHS external comparator group exhibited a decline in all timed function tests, except for time to climb 4 stairs. Velocity in the time to run/walk 10 m test significantly improved in viltolarsen-treated participants at weeks 13 and 25 compared with a decline in controls from CINRG DNHS (change at 25 weeks compared with baseline: viltolarsen, 0.23 m/s; control, −0.04 m/s). The 6-minute walk test showed significant improvement at week 25 in viltolarsen-treated participants, whereas results from CINRG DNHS controls declined over the same period (change at 25 weeks compared with baseline: viltolarsen, 28.9 m; control, −65.3 m). Significant improvements in time to stand from supine were observed (change at 25 weeks compared with baseline: viltolarsen, −0.19 s; control, 0.66 s). Velocity in the time to stand from supine test and time to climb 4 stairs test as well as North Star Ambulatory Assessment similarly displayed improvement or stabilization, but the differences between viltolarsen treatment and external comparator controls were not significant. Measures of muscle strength by isometric testing showed no differences between viltolarsen-treated participants and the CINRG DNHS external comparator control group.

Figure 3. Change in Timed Function Tests in Viltolarsen-Treated Participants and Cooperative International Neuromuscular Research Group (CINRG) Duchenne Natural History Study (DNHS).

The change in timed function tests of viltolarsen-treated participants from both dose groups (blue) and CINRG DNHS steroid-treated, age-matched comparators (orange) are shown. Assessments were performed at baseline and the 13-week and 25-week visits.

Safety

Overall, 15 of 16 participants (94%) experienced treatment-emergent AEs (Table 2). There were no treatment-emergent serious AEs (Table 2). No treatment-emergent AEs required dose reduction, interruption, or discontinuation of the study drug, and no deaths were reported. Most participants with treatment-emergent AEs recovered by the end of the study. In the 2 participants with unresolved AEs, both events were mild. Three participants had injection-site reactions; all were mild and resolved on the day of onset. No treatment-emergent AEs were related to the study drug, as assessed by study investigators. No single treatment-emergent AE was reported in more than 1 participant during the first study period. The most common treatment-emergent AEs in the second study period were cough (2 participants in each dose cohort) and nasopharyngitis (4 participants in the high-dose cohort). Diarrhea and vomiting were reported in 2 participants in the second study period.

Table 2. Safety Summarya.

| Outcome | No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-wk Double-blinded placebo-controlled period | 20-wk Open-label treatment period | Total (n = 16) | ||||

| Placebo (n = 5) | Low-dose group (n = 6) | High-dose group (n = 5) | Low-dose group (n = 8) | High-dose group (n = 8) | ||

| AEs | ||||||

| AEs, No. | 5 | 6 | 6 | 13 | 28 | 61 |

| Treatment-emergent AEs, No. | 5 | 6 | 6 | 13 | 28 | 58 |

| Patients with any treatment-emergent AEs | 3 (60) | 4 (67) | 4 (80) | 5 (63) | 7 (88) | 15 (94) |

| Patients with any drug-related treatment-emergent AE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Patients with any CTCAE ≥grade 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Patients who discontinued treatment due to treatment-emergent AE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Patients with any serious treatment-emergent AEs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Patients who died | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment-emergent AEs by preferred term (occurring in >1 patient) | ||||||

| Infections and infestations | 1 (20) | 0 | 1 (20) | 1 (13) | 5 (63) | 6 (38) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 1 (20) | 0 | 1 (20) | 0 | 4 (50) | 4 (25) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 0 | 1 (17) | 2 (40) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | 7 (44) |

| Cough | 0 | 0 | 1 (20) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | 5 (31) |

| Nasal congestion | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (13) | 0 | 2 (13) |

| Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications | 1 (20) | 0 | 1 (20) | 2 (25) | 1 (13) | 4 (25) |

| Contusion | 0 | 0 | 1 (20) | 0 | 1 (13) | 2 (13) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorder | 1 (20) | 0 | 1 (20) | 2 (25) | 1 (13) | 4 (25) |

| Arthralgia | 1 (20) | 0 | 1 (20) | 0 | 0 | 2 (13) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (13) | 2 (25) | 3 (19) |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (13) | 1 (13) | 2 (13) |

| Vomiting | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (25) | 2 (13) |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.

The low-dose cohort received 40 mg/kg per week of viltolarsen; the high-dose cohort received 80 mg/kg per week.

No changes from baseline in clinical laboratory values for blood and urine were clinically meaningful. Serum creatine kinase values were elevated and highly variable, as expected in DMD.

Discussion

Here, we report that systemic treatment of patients with DMD amenable to exon 53 skipping with viltolarsen induced significant de novo dystrophin production and demonstrated clinical improvement of timed function tests compared with matched historical controls. De novo production of dystrophin is accepted by the US Food and Drug Administration as a surrogate outcome for DMD drug approval.15 Viltolarsen-treated study participants exhibited significantly increased dystrophin expression at week 25 as measured by Western blot, with mean (SD) dystrophin levels of 5.7% (2.4%) in the low-dose group and 5.9% (4.5%) in the high-dose group. Although direct comparisons cannot be made across studies, dystrophin levels induced by viltolarsen are the highest reported in clinical trials of exon-skipping therapies to date.16,17 Further, substantial increases in viltolarsen-induced dystrophin levels were also seen when measured by MS quantification and IF localization.

In patients with DMD and BMD, dystrophin levels have been shown to partially correlate with clinical severity.5,18,19 The milder BMD clinical phenotype can be associated with dystrophin levels as low as 3%.5,18 In recent studies of muscle biopsies from patients with BMD, patients with DMD, and healthy controls, modestly higher dystrophin levels (2% to 7% of normal) were associated with better functional outcome with older age at loss of ambulation relative to other patients with DMD.19,20,21,22 These data suggest that dystrophin levels as low as 2% of normal are associated with better functional outcomes. In the current study, 15 of 16 participants (94%) treated with viltolarsen achieved dystrophin levels greater than 2% of normal, and 14 of 16 (88%) reached levels greater than 3% of normal.

Early treatment of DMD is important for improved clinical outcomes.23,24 Although restoring some dystrophin through exon-skipping therapy is thought to slow disease progression, it cannot restore muscle that is already lost.4,25 Patients with DMD are able to regenerate muscle tissue early in life; however, as the disease progresses, muscle fibers are replaced by adipose and fibrous connective tissue.26 Patients with DMD experience physical decline, muscle loss, and reduction in timed function test scores at approximately 7 years of age.27,28 Therefore, it is important to begin treatment with therapies that restore dystrophin as early as possible within the course of muscle tissue destruction that is already ongoing at birth.23 The Food and Drug Administration supports the early treatment of patients with DMD to benefit muscle health. In fact, clinical data show that delayed treatment may be associated with reduced scores on timed function tests.29 To our knowledge, this is the first report of the efficacy and safety of exon-skipping therapy in patients with DMD younger than 5 years.29,30,31,32 Patients as young as 4 years exhibited improvements in dystrophin levels and timed motor tests following viltolarsen treatment.

Limitations

The main study limitation is the small sample size. However, given the rarity of DMD and small population of patients with DMD amenable to exon 53 skipping, the trial described herein provides supportive data of viltolarsen despite the sample size. Also, the trial design and sample size are comparable with other clinical trials performed in this patient population.17 An additional limitation is inherent in the assessments of muscle function that were compared with an external control group. Improvements in muscle function over the course of the study showed some variability, with certain results demonstrating improvement while others demonstrated stabilization. This may have been affected by the level of sensitivity to change of functional assessments during the disease progression in this age group. Furthermore, use of an external control group, while appropriate for a phase 2 study in a rare disease with a surrogate primary outcome, is less rigorous than a randomized, placebo-controlled design.

Conclusions

The results support the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of viltolarsen for treatment of patients with DMD variants amenable to exon 53 skipping, thus potentially providing a new therapeutic option to an additional population of patients with DMD.

Trial protocol.

eMethods.

eTable 1. DMD variant type.

eTable 2. Mean dystrophin induction.

eFigure. Study design.

Data sharing statement.

References

- 1.Hoffman EP, Brown RH Jr, Kunkel LM. Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell. 1987;51(6):919-928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90579-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uaesoontrachoon K, Srinivassane S, Warford J, et al. Orthogonal analysis of dystrophin protein and mRNA as a surrogate outcome for drug development. Biomark Med. 2019;13(14):1209-1225. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2019-0242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darin N, Tulinius M. Neuromuscular disorders in childhood: a descriptive epidemiological study from western Sweden. Neuromuscul Disord. 2000;10(1):1-9. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8966(99)00055-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bladen CL, Salgado D, Monges S, et al. The TREAT-NMD DMD Global Database: analysis of more than 7,000 Duchenne muscular dystrophy mutations. Hum Mutat. 2015;36(4):395-402. doi: 10.1002/humu.22758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman EP, Fischbeck KH, Brown RH, et al. Characterization of dystrophin in muscle-biopsy specimens from patients with Duchenne’s or Becker’s muscular dystrophy. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(21):1363-1368. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198805263182104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bushby K, Finkel R, Birnkrant DJ, et al. ; DMD Care Considerations Working Group . Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and pharmacological and psychosocial management. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(1):77-93. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70271-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beggs AH, Hoffman EP, Snyder JR, et al. Exploring the molecular basis for variability among patients with Becker muscular dystrophy: dystrophin gene and protein studies. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;49(1):54-67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bello L, Gordish-Dressman H, Morgenroth LP, et al. ; CINRG Investigators . Prednisone/prednisolone and deflazacort regimens in the CINRG Duchenne Natural History Study. Neurology. 2015;85(12):1048-1055. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verhaart IEC, Aartsma-Rus A. Therapeutic developments for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(7):373-386. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0203-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Komaki H, Nagata T, Saito T, et al. Systemic administration of the antisense oligonucleotide NS-065/NCNP-01 for skipping of exon 53 in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(437):eaan0713. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aan0713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe N, Nagata T, Satou Y, et al. NS-065/NCNP-01: an antisense oligonucleotide for potential treatment of exon 53 skipping in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2018;13:442-449. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2018.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonald CM, Henricson EK, Abresch RT, et al. ; Cinrg Investigators . The cooperative international neuromuscular research group Duchenne natural history study—a longitudinal investigation in the era of glucocorticoid therapy: design of protocol and the methods used. Muscle Nerve. 2013;48(1):32-54. doi: 10.1002/mus.23807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonald CM, Henricson EK, Abresch RT, et al. ; CINRG Investigators . Long-term effects of glucocorticoids on function, quality of life, and survival in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2018;391(10119):451-461. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32160-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Extension study of NS-065/NCNP-01 in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03167255. Updated March 21, 2019. Accessed January 6, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03167255

- 15.US Food and Drug Administration . Table of surrogate endpoints that were the basis of drug approval or licensure. Accessed December 6, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-resources/table-surrogate-endpoints-were-basis-drug-approval-or-licensure

- 16.Charleston JS, Schnell FJ, Dworzak J, et al. Eteplirsen treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: exon skipping and dystrophin production. Neurology. 2018;90(24):e2146-e2154. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muntoni F, Frank D, Sardone V, et al. Golodirsen induces exon skipping leading to sarcolemmal dystrophin expression in Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients with mutations amenable to exon 53 skipping (S22.001). Neurology. 2018;90(15)(suppl):S22.001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Bergen JC, Wokke BH, Janson AA, et al. Dystrophin levels and clinical severity in Becker muscular dystrophy patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(7):747-753. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bello L, Campadello P, Barp A, et al. Functional changes in Becker muscular dystrophy: implications for clinical trials in dystrophinopathies. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32439. doi: 10.1038/srep32439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beekman C, Janson AA, Baghat A, van Deutekom JC, Datson NA. Use of capillary Western immunoassay (Wes) for quantification of dystrophin levels in skeletal muscle of healthy controls and individuals with Becker and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0195850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pane M, Mazzone ES, Sormani MP, et al. 6 Minute walk test in Duchenne MD patients with different mutations: 12 month changes. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e83400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang RT, Barthelemy F, Martin AS, et al. DMD genotype correlations from the Duchenne Registry: endogenous exon skipping is a factor in prolonged ambulation for individuals with a defined mutation subtype. Hum Mutat. 2018;39(9):1193-1202. doi: 10.1002/humu.23561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Food and Drug Administration . Duchenne muscular dystrophy and related dystrophinopathies: developing drugs for treatment guidance for industry. Accessed December 6, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/duchenne-muscular-dystrophy-and-related-dystrophinopathies-developing-drugs-treatment-guidance

- 24.Institute for Clinical and Economic Review . Deflazacort, eteplirsen, and golodirsen for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: effectiveness and value. Accessed December 6, 2019. https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/ICER_DMD_Draft_Scope_011119-1.pdf

- 25.Cordova G, Negroni E, Cabello-Verrugio C, Mouly V, Trollet C. Combined therapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy to optimize treatment efficacy. Front Genet. 2018;9:114. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blake DJ, Weir A, Newey SE, Davies KE. Function and genetics of dystrophin and dystrophin-related proteins in muscle. Physiol Rev. 2002;82(2):291-329. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazzone ES, Pane M, Sormani MP, et al. 24 month longitudinal data in ambulant boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e52512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendell JR, Goemans N, Lowes LP, et al. ; Eteplirsen Study Group and Telethon Foundation DMD Italian Network . Longitudinal effect of eteplirsen versus historical control on ambulation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(2):257-271. doi: 10.1002/ana.24555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendell JR, Rodino-Klapac LR, Sahenk Z, et al. ; Eteplirsen Study Group . Eteplirsen for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(5):637-647. doi: 10.1002/ana.23982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goemans N, Mercuri E, Belousova E, et al. ; DEMAND III study group . A randomized placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of an antisense oligonucleotide, drisapersen, in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018;28(1):4-15. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2017.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.BioMarin announces withdrawal of market authorization application for Kyndrisa™ (drisapersen) in Europe. News release. Globe Newswire; May 31, 2016. Accessed December 6, 2019. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2016/05/31/844933/0/en/BioMarin-Announces-Withdrawal-of-Market-Authorization-Application-for-Kyndrisa-drisapersen-in-Europe.html

- 32.Phase I/II study of SRP-4053 in DMD patients. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02310906. Updated June 12, 2019. Accessed December 6, 2019. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02310906

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol.

eMethods.

eTable 1. DMD variant type.

eTable 2. Mean dystrophin induction.

eFigure. Study design.

Data sharing statement.