Abstract

Glioma stem cells (GSCs), or stem cell-like glioma cells, isolated from malignant glioma cell lines, were capable of producing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). However, the exact role of such tumour cells in angiogenesis remains unknown. In this study, we isolated a small proportion of CD133+ GSCs from the human glioblastoma cell line U87 and found that these GSCs possessed multipotent differentiation potential and released high levels of VEGF as compared with CD133− tumour cells. The CD133+ GSCs also formed larger xenograft tumours that contained higher VEGF immunoreactivity and denser microvessels. Moreover, GSCs expressed a functional G protein-coupled formylpeptide receptor FPR, which was activated by a chemotactic peptide ligand, N-formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLF), to mediate calcium flux and the production of VEGF by GSCs. Our results indicate that FPR expressed by human GSCs may play an important role in glioma angiogenesis.

Keywords: cancer stem cells, glioma, angiogenesis, formylpeptide receptor, fMLF, VEGF

Introduction

Evidence is accumulating that malignant tumours contain cancer stem cells (CSCs), otherwise termed tumour stem cells (TSCs) [1,2], which constitute a minor fraction of a given tumour yet with the capacity of self-renewing, multipotent differentiation, exclusive tumourigenicity and drug resistance [3,4]. The CSCs hypothesis presumed that despite rigorous therapy, as long as CSCs remain in the host, clinical relapse of tumour would be inevitable [4]. This has been supported by observations in models of breast cancer [2], acute myeloid leukaemia [5,6] and brain tumours [7], in which isolated CSCs when injected into experimental animals initiate new tumours.

In human glioblastoma, CD133 has been considered an important marker for CSCs and such cells are also positive for neural stem cell marker, nestin, and can differentiate into glioma cells expressing glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and other glial markers [8,9]. Glioma stem cells (GSCs) also are capable of self-renewal, forming neurosphere-like spheroids, initiating xenograft tumours and differentiating into multiple cell types of the neuroglial lineage.

One of the important issues for CSCs is whether they contribute to the process of neovascularization, including angiogenesis and vasculogenesis. Recent studies have shown that GSCs produce higher levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and the VEGF neutralizing antibody Bevacizumab inhibited angiogenesis and the growth of xenograft tumours formed by CD133+ glioma cells [10]. These results suggest an important role for GSCs in tumour angiogenesis and elucidation of the mechanistic basis will benefit the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Our previous study showed that human glioblastoma cells express a G protein-coupled receptor FPR, which, upon activation by the bacterial chemotactic peptide N-formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLF) or agonists released by necrotic glioma cells, promotes the directional migration, growth and production of VEGF [11,12] and the angiogenic chemokine interleukin-8 (CXCL8) by tumour cells [13]. In this study, we investigated the expression of FPR by GSCs from a glioblastoma cell line U87 and its role in GSC production of VEGF. Our results indicate that CD133+ GSCs express functional FPR and release increased levels of VEGF in response to FPR agonist stimulation.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human glioblastoma cell line U87 (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were grown in Dulbeco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). In all experiments, cells were maintained in flasks at 37 °C in humidified 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere.

Flow cytometry

To identify GSCs, cultured U87 cells and cells from CD133+ xenograft tumours were trypsinized (0.05% trypsin:0.01% EDTA), then were resuspended at 106 cells in 80 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2, with 0.5% BSA and 2 mm EDTA) plus 20 μl FcR Blocking Reagent (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-059-901). The cells were incubated with 10 μl CD133/2-PE (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-090-853) for 10 min in the dark at 4°C followed by washing with 10–20 volumes of buffer. The cell pellets were resuspended in the buffer to detect the ratio of CD133+ fraction by flow cytometry.

Separation of GSCs

GSCs were separated by trypsinizing U87 cells at 80% confluence in flasks, resuspending the cells at 106 cells in 300 μl buffer and 1 μl CD133/1 MicroBeads, and selection with CD133 Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-050-801) on MACS MS columns (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-042-201). CD133+ and CD133− cell populations were cultured in stem cell medium consisting of DMEM/F12 with 20 ng/ml EGF and 20 ng/ml bFGF (Pepro Tech Inc., 100-15 and 100-188).

RT–PCR

Total RNA from CD133+ and CD133− cells were isolated with RNAiso reagent (Takara, Dalian, China) and 0.5 μg RNA from each group were used for RT–PCR with a two-step RT–PCR kit (Boer, Hangzhou, China). For FPR, the following primers were used: 5’-CCTCACATTGCCAGTTATCATTC-3’ (sense) and 5’-CTTTGCCTGTAACTCCACCTCT-3’ (antisense) to yield a 586 bp product. The β-actin gene was determined as control with the primers: 5’-GTCCTGTGGCATCCACGAAAC-3’ (sense) and 5’-GCTCCAACCGACTGCTGTCA-3’ (antisense) to yield a 500 bp product. After reverse transcription, the PCR parameters included 5 min at 95 °C for 1 cycle, 30 s at 95 °C, 45 s at 60.5 °C and 1 min at 72 °C for 30 cycles, with extension for 10 min at 72 °C. The RT–PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and identified by ethidium bromide staining. For quantification, the pixel intensity of each RT–PCR product band was determined using an Image/J program (NIH Image, USA) normalized against the β-actin band.

Immunochemical staining

U87 cells were washed with 0.01 m PBS and fixed in 75% ethanol for 20 min at room temperature. After washing in 0.01 m PBS and blocked with 5% BSA or normal goat serum for 1 h at 37 °C in a humidified chamber, the cells were incubated with a monoclonal anti-human CD133/2-PE (1:11; Militeny Biotec, 130-090-853) overnight at 4 °C. Sorted tumour cells and cells isolated from CD133+ xenograft tumours were stained with the following antibodies: anti-human CD133/1 (mouse monoclonal; 1:5; Milteny Biotec, 130-090-422), anti-human nestin (mouse monoclonal; 1:100; Chemicon, AB5922) and anti-human GFAP (rabbit polyclonal; 1:100; Sigma, G9269). The binding of primary antibodies was detected with F1TC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co. Ltd, China; ZF-0312, and ZF-0311). The cells were counterstained with propidium iodide (PI, 5 μg/ml, Sigma, 81 845) or 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 10 μg/ml, Sigma, 32670) to mark nuclei.

Double immunofluorescence staining was used for detecting the co-expression of CD133 and FPR in tumour spheres. Briefly, tumour spheres were fixed in paraformaldehyde for 20 min and blocked with normal goat serum. Anti-human CD133 antibody was then added to the cells for overnight. After revealing the cell bound primary antibodies by TRITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co. Ltd; ZF-0313), the samples were incubated with goat anti-human FPR (goat polyclonal; 1:30; Santa Cruz, sc-13 198) for another 12 h. The cell-bound FPR antibody was detected by FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG. Cell nuclei were labelled with DAPI. The samples were examined with a confocal laser scanning microscope. Isotype-matched IgGs were used as negative controls.

For spheroid staining, spheroids were planted on poly-d-lysine precoated slides and were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. The slides were then treated with 0.01 m PBS containing 5% BSA, and then stained with the following antibodies: anti-human CD133/1, anti-human nestin, anti-human GFAP and anti-human FPR. The cell-bound primary antibodies were detected with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG or FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG (Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co. Ltd, China; ZF-0314). The cells were counterstained with DAPI to mark nuclei. Specimens were examined with a laser confocal scanning microscope.

Paraffin-embedded xenograft tumours were sliced into 6 μm sections and mounted on glass slides for staining with haematoxylin for 2 min, counterstained with eosin (H&E). Tumour sections were also stained with anti-human vimentin (mouse monoclonal, 1:200; Sigma, V6389) and anti-human Ki67 (mouse monoclonal, 1:100; Sigma, P6834). ABC kit was used to reveal cell-bound antibodies according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

VEGF immunofluorescence was detected on 6 μm frozen sections from xenograft tumours. Sections fixed in cold acetone for 15 min were treated with normal goat serum and then stained with anti-human VEGF antibody (mouse monoclonal, 1:100; Sigma, 4762). FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG was used to detect cell bound primary antibody. Nuclei were marked with PI. Specimens were examined with a confocal laser scanning microscope.

Tumour implantation

To evaluate the tumourigenicity of CD133+ GSCs, SCID mice (Laboratory Animal Center, Third Military Medical University, Chongqing, China), aged 4–6 weeks, were subcutaneously implanted with CD133+ GSCs (1 × 104/mouse) or CD133- tumour cells (2 × 104/mouse) in 100 μl serum-free DMEM/F12 in the right chest wall. The experiments were repeated twice and each group contained at least six mice. Tumours were measured once a week for 8 weeks, and tumour volume (TV) was calculated as follows: Tv = 1 [length ° w2 (width)] ° 0.52 [13]. Tumour-bearing mice were sacrificed after 8 weeks and the tumours were excised for analysis of CD133+ GSCs by flow cytometry. Cells from CD133+ (1 × 104) xenograft tumours were implanted again subcutaneously into SCID mice. Animal care was provided in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Analysis of microvessel density (MVD)

Frozen tumour sections at 6 μm blocked with normal goat serum were incubated at 4 °C overnight with anti-mouse CD105 antibody (rat monoclonal; 1:100; Santa Cruz, sc-71043). The cell-bound antibody was detected with ABC kit Regions of highest vessel density were identified under low magnification (°50), followed by counting blood vessels in at least four high powered (°200) fields by a pathologist with no knowledge of the sample identity [13].

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ELISA was used to determine VEGF concentration in tumour cell culture supernatants (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA; DVE00). CD133+ GSCs and CD133− cells at 105 were incubated in stem cell medium at 37 °C for different time periods. The supernatants were harvested for measurement of VEGF. To evaluate the effect of FPR activation, CD133+ GSCs were cultured in stem cell medium to form spheroids, before treatment for different time intervals with 10−4 nw fMLF (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The supernatants were harvested to measure VEGF.

Calcium flux

Microfluorimetry was used for measurements of intracellular calcium [Ca2+]i mobilization. GSC spheroids were grown on poly-D-lysine-coated coverslips and loaded with 5 μM Fluo-4/AM (Molecular Probes, F-14217) as a fluorescent indicator. After washing three times, the coverslips were transferred into assay buffer (D-Hanks without Ca2+). Digital images were captured and recorded every 5 min. Different concentration of fMLF were added when the tenth image was captured, followed by sequential recording of 200 images. The number of pixels and relative fluorescence intensity were calculated using Leica 5.0 confocal analysis software.

Statistical analyses

All experiments were performed at least three times and the results were from representative experiments. The data were analysed with computer-aided SPSS 10.0 statistical software. Parametric data are expressed as the mean ± SD. When two groups were compared, the unpaired dependent-samples t-test was used. One-way ANOVA was used to determine the statistical significance of the differences among multiple groups. For comparison of protein expression levels, independent-samples t test was used. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Isolation of CD133+ GSCs from U87 glioblastoma cell line

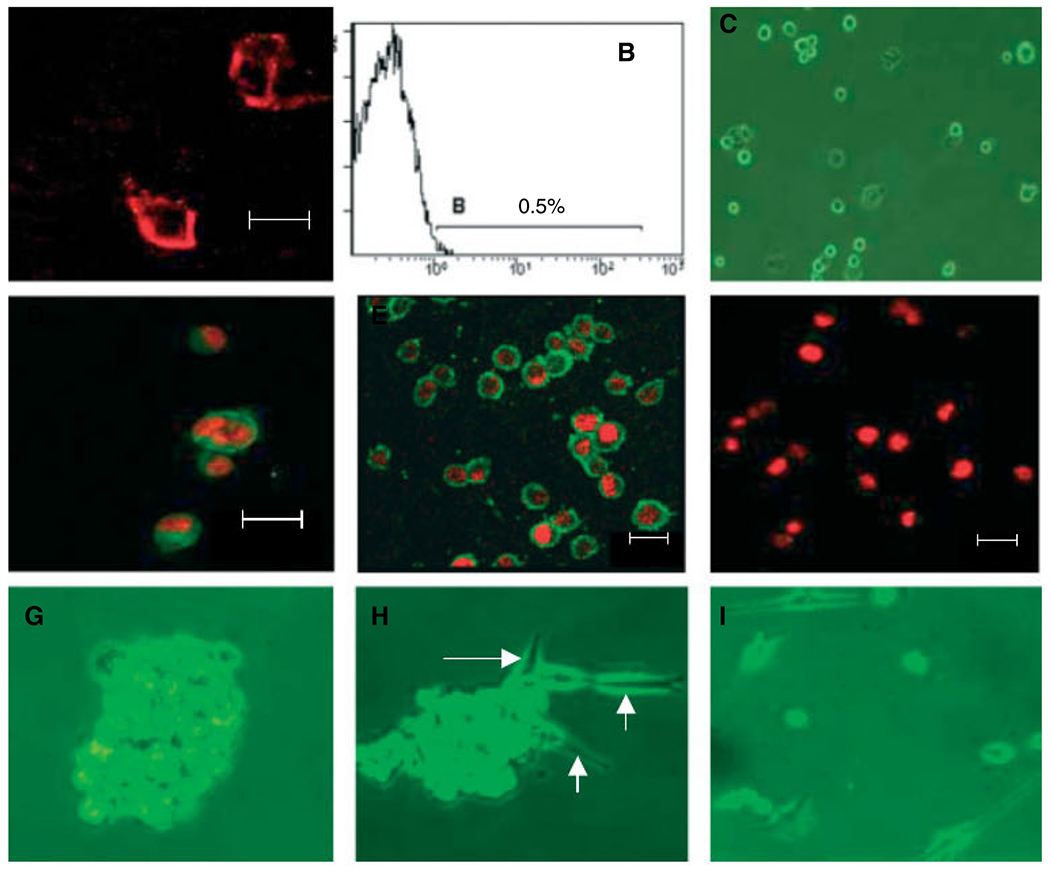

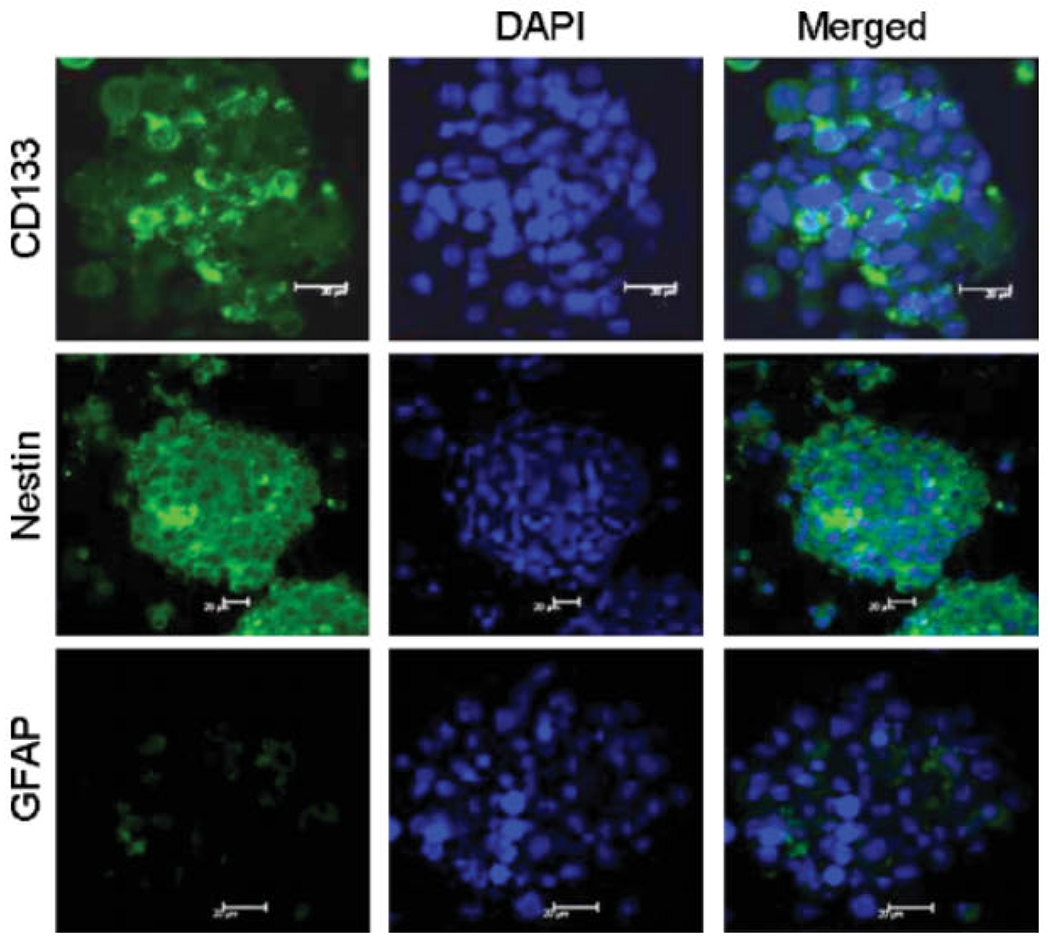

Immunostaining indicated that only a very minor proportion of U87 cells expressed CD133 (Figure 1A). Flow cytometry shown in Figure 1B confirmed that 0.5% CD133+ cells existed in U87 cell line. We then used CD133 magnetic beads to enrich GSCs (Figure 1C) to a purity of 60% (data not shown). The enriched CD133+ cells expressed the neural stem cell marker nestin but not GFAP (Figure 1D–F) and they formed spheroids when cultured in stem cell medium (Figure 1G). Under differentiation culture conditions (medium containing FCS), the spheroids differentiated into astrocytes and grew in monolayer (Figure 1H). CD133− cells grew in monolayer without the formation of spheroids when cultured in stem cell medium (Figure 2), with the expression of GFAP (data not shown). In contrast, cells in spheroids were positive for CD133 and nestin, but not GFAP (Figure 2). Thus, we were able to isolate an enriched population of CD133+ GSCs from the U87 cell line.

Figure 1.

GSCs isolated from U87 cells. (A) U87 cells were cultured on cover-slips and stained with anti-CD133/PE; (B) section of CD133+ cells in U87 cells by flow cytometry; (C–F) detection of markers expressed by CD133+ GSCs; (C) CD133+ GSCs; (D) CD133; (E) nestin; (F) GFAP; (G) CD133+ cells forming spheroids of about 200 cells after 2 weeks in stem cells media; (H) spheroids in medium containing FCS differentiate into glioma cells (arrows); (I) CD133− cells cultured in stem cell medium in monolayer. (A, D, E and F) Immunofluorescence staining and laser scanning microscopy. Nuclei were labelled with PI (red). Scale bar = 20 μm

Figure 2.

Phenotype of CD133+ cell spheroids. Spheroids formed by CD133+ cells in stem cell media expressed CD133 and nestin without GFAP. Immunofluorescence staining and laser scanning microscopy. Nuclei were labelled with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 20 μm

CD133+ GSCs initiate xenograft tumours

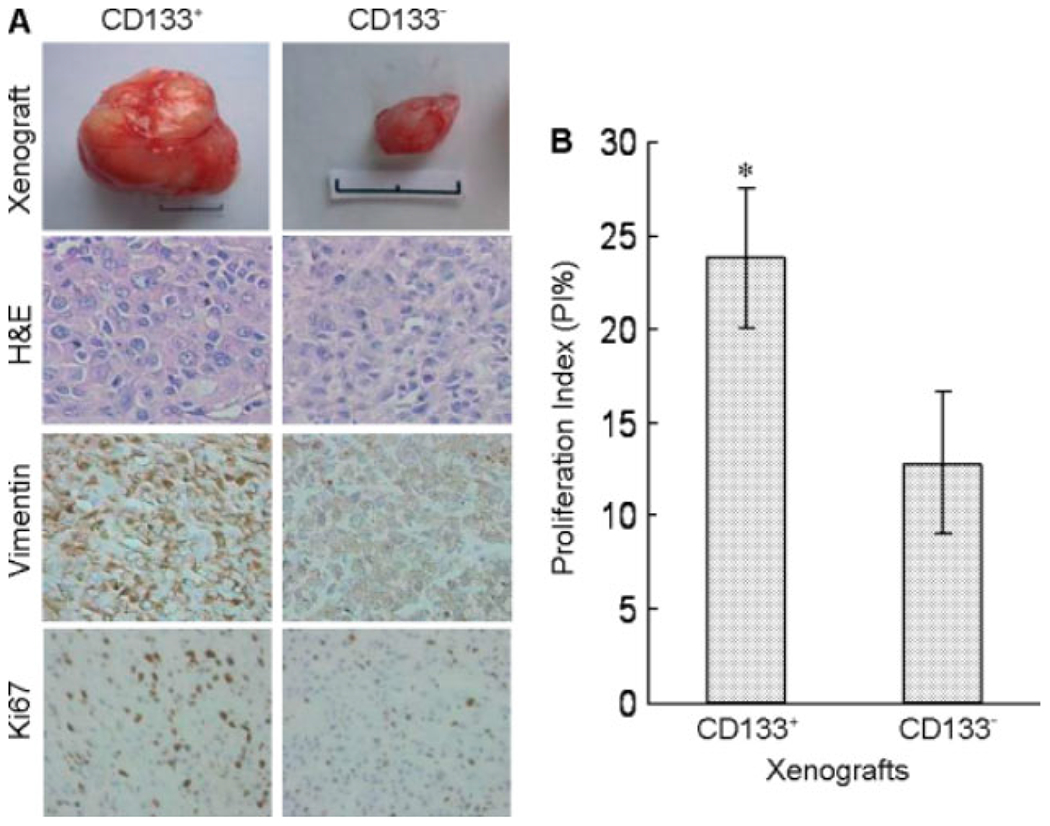

We compared the capacity of CD133+ and CD133− cells to initiate tumours in SCID mice. All mice implanted with 104 CD133+ cells developed tumours at 5–8 weeks, whereas only one of the mice (1/6) injected with CD133− cells grew a tumour at 6 weeks. At 8 weeks the size of tumours formed by CD133+ cells (8.36 ± 2.24 cm3) was significantly larger than a lone tumour formed by CD133“ cells (0.09 cm3; Figure 3A). As compared with CD133“ cell formed tumours, tumours formed by CD133+ cells showed a poorer differentiation pattern with more abundant anaplastic and proliferative cells positive for the malignant glioma marker vimentin and Ki67, a marker for proliferating cells. CD133+ xenograft tumours grew more rapidly, with considerably higher level expression of vimentin as compared with CD133“ xenograft tumour (Figure 3A, B).

Figure 3.

Tumour formation by CD133+ GSCs in vivo. CD133+ or CD133− cells isolated from U87 cells were implanted (104 cells/mouse) subcutaneously into SCID mice, which were sacrificed after 8 weeks. (A) The size of xenograft tumours with H&E staining, as well as vimentin and Ki67 immunolabelling. (B) Rate of tumour growth expressed as proliferation index (Pl%). *p < 0.05, significantly higher rate of growth as compared with CD133− cell tumour. Scale bar = 1 cm

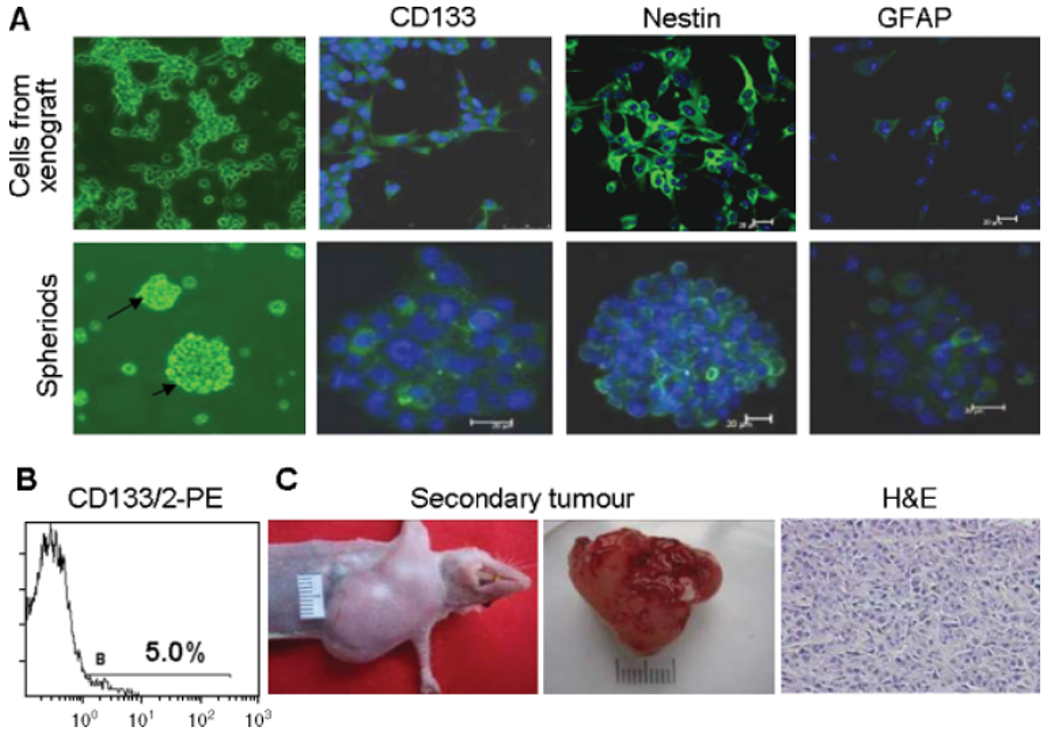

Self-renewal of CD133+ GSCs

Many cells isolated from CD133+ xenograft tumours expressed CD133 and nestin, with only a few cells expressing GFAP (Figure 4A). Flow cytometry showed that the CD133+ fraction accounted for 5.0% of total cells obtained from CD133+ xenograft tumours and such cells also formed spheroids in vitro expressing CD133 and nestin with a very weak expression of GFAP (Figure 4A, B). Single-cell suspension was prepared from tumours formed by CD133+ GSCs and 104 cells were re-implanted into SCID mice. These cells formed tumours at as early as 3 weeks, a rate faster than primary CD133+ cells from U87 cells. The secondary xenograft tumours recapitulated the pathological pattern of the primary xenograft tumours (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Self-renewal of CD133+ GSCs. (A) Detection of CD133, nestin and GFAP in cells from CD133+ xenograft tumours and spheroids formed by these cells. Immunofluorescence staining and laser scanning microscopy. Nuclei were labelled with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 20 μm. (B) Detection of CD133 in cells isolated from CD133+ xenograft tumours. (C) Secondary tumours formed by 104 cells derived from CD133+ xenograft tumours in SCID mice at 3 weeks. H&E staining showing histological features similar to primary xenograft tumours formed by CD133+ cells from the U87 cell line

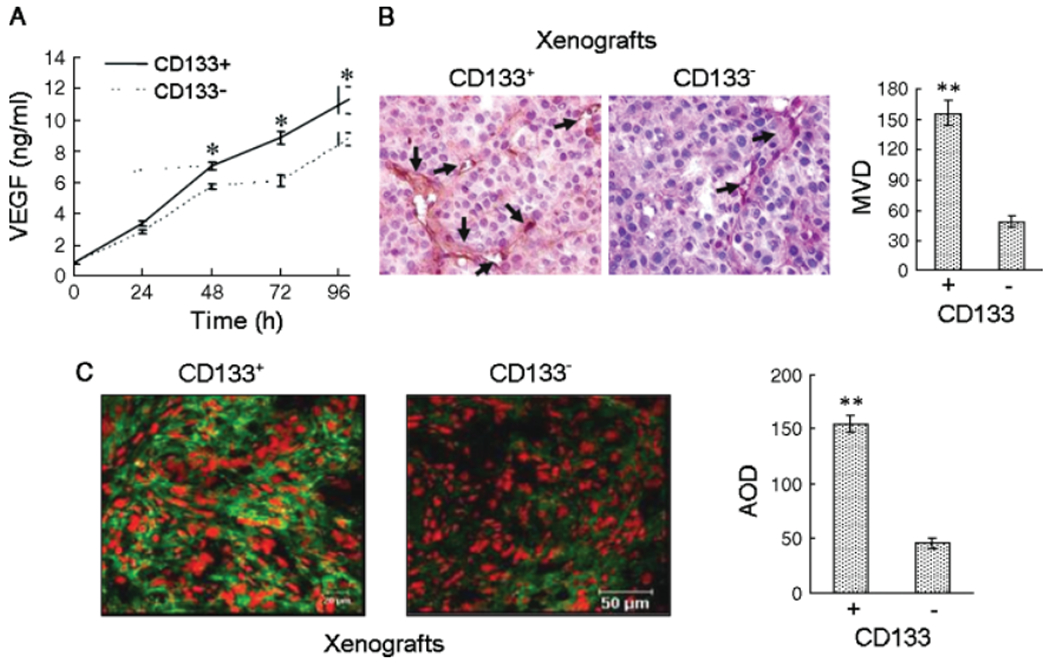

Production of VEGF by CD133+ GSCs

We next examined the capacity of CD133+ and CD133− cells to produce VEGF in vitro. As compared with CD133− cells, CD133+ cells released higher levels of VEGF in the culture supernatant (Figure 5A). In animals, tumours formed by CD133+ cells contained higher density of microvessels as labelled by CD105 (Figure 5B) and higher levels of VEGF immunoreactivity as compared to CD133− cell tumours (Figure 5B, C). These results indicate more rigorous angiogenesis occurring in tumours formed by CD133+ GSCs, which involves increased production of VEGF.

Figure 5.

Production of VEGF by CD1331 GSCs. (A) Levels of VEGF measured in the supernatants of CD133+ and CD133− tumour cells. *p < 0.05, compared with the VEGF produced by CD133− cells. (B) Elevated blood vessel density in CD133+ xenograft tumours determined by immunohistochemical staining with CD105. **p < 0.01, compared with CD133− cells. (C) Higher level of VEGF in CD133+ xenograft tumours. Average optical density (AOD) was used to quantify fluorescence intensity. **Significantly increased level of protein expression in tumours formed by CD133+ cells as compared to CD133− cells (p < 0.01). Nuclei were counterstained with PI in red colour. Immunofluorenscence staining and laser confocal scanning microscopy. Scale bar = 20 μm or 50 μm

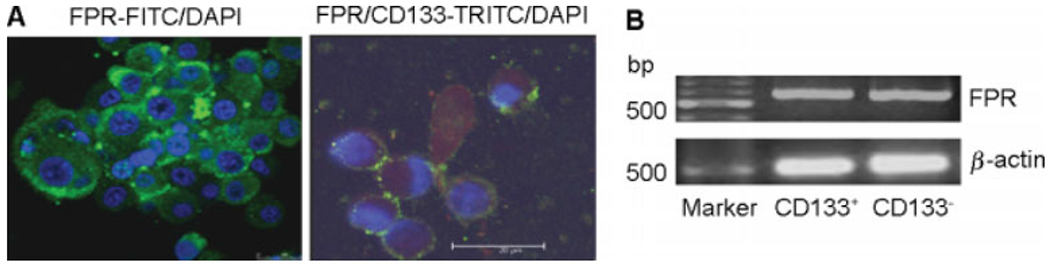

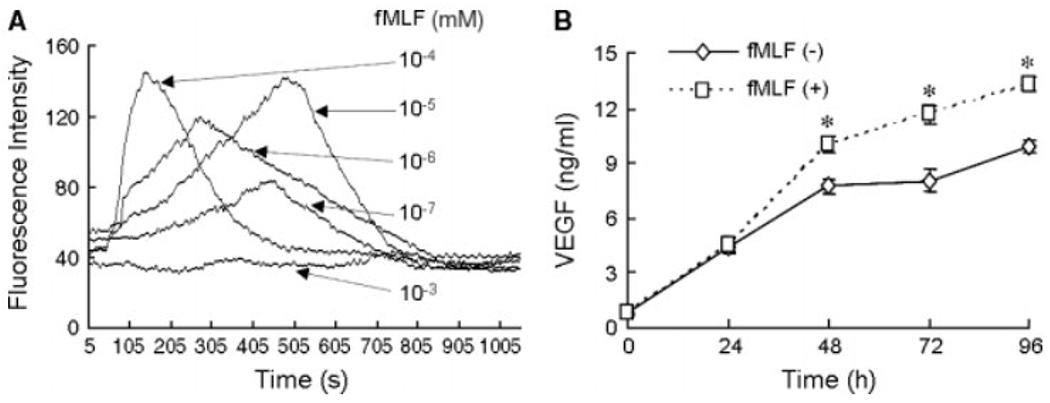

CD133+ GSCs express functional FPR

A recent study reported [14] that FPR expressed by mesenchymal stem cells might play an important role in mediating cell adhesion, migration and homing to injured tissues. Our previous study showed that FPR on U87 cells, when activated by its agonists, promoted tumour cell production of VEGF [13]. In this study, we additionally found that spheroids formed by CD133+ GSCs expressed both FPR and CD133 on the cell surface (Figure 6A). GSCs also expressed FPR mRNA at a level comparable to CD133“ cells (Figure 6B). FPR expressed by CD133+ cells was functional because stimulation of CD133+ cells with the FPR agonist peptide fMLF induced a dose-dependent calcium mobilization, a typical function of FPR in both myeloid cells and U87 cells (Figure 7A) [12]. CD133+ cells stimulated by fMLF also increased their release of VEGF in the culture supernatant (Figure 7B). Thus, FPR expressed by CD133+ GSCs may contribute to the production of VEGF in response to agonist activity potentially existing in the tumour microenvironment.

Figure 6.

The expression of functional FPR by CD133+ GSCs. (A) FPR and CD133 expressed on the GSCs within spheroid. Nuclei were revealed with DAPI in blue colour. Laser confocal scanning microscopy. Scale bar 20 μm. (B) FPR mRNA expression in CD133+ and CD133− cells

Figure 7.

The function of FPR on CD133+ GSCs. (A) Intracellular calcium mobilization induced by fMLF in CD133+ cells isolated from U87 cell line. (B) VEGF in supernatants of CD133+ cells stimulated with 10−4 mm fMLF for 48, 72 and 96 h. *p < 0.05, as compared with supernatants from unstimulated cells

Discussion

Identification of CSCs has greatly promoted the understanding of carcinogenesis and tumour progression [15]. CSCs may be present in various cancer cell lines maintained in culture, even after many years [9]. Studies of acute myeloid leukaemia have shown that only 0.1–1% cells possess leukaemia-initiating activity and they exhibit markers and properties of normal haematopoietic stem cells [16,17]. In solid tumours, stem cells may express organ-specific markers. For instance, stem cells from human brain tumours are positive for CD133 (human prominin-1/AC 133), a transmembrane glycopotein used to isolate stem cells from the haematopoietic system and the brain [8,18–20]. In vitro analysis indicates that in a bulk brain tumour cell population, only CD133+ cells were capable of self-renewal and proliferation.

Glioblastomas display conspicuous morphological heterogeneity that reflects their origin of different populations of astrocytes and possibly ependymal cells. CSCs isolated from ependymomas were similar to neural precursor cells in radial glia [21]. Our study indicates that human glioblastoma cell line U87 contained a small population of CD133+ cells with the capacity of self-renewal, forming spheroids and differentiating into progeny cells with the property similar to their parental cell line. When implanted in SCID mice, CD133+ cells initiated more rapidly growing tumours than their CD133− counterpart cells. Thus, in accordance with the literature [16], our CD133+ GSCs exhibited prominent tumorigenicity and the capacity to produce angiogenic VEGF that is critically involved in endothelial cell recruitment, proliferation and vasculature formation to support the expansion of malignant tumours [22–28].

Our study also revealed that, similar to the U87 cell line [11], CD133+ GSCs expressed the G-protein coupled receptor FPR, which when activated by bacteria or host derived chemotactic agonists, mediates tumour cell chemotaxis, calcium mobilization and production of VEGF. In this study, we found that fMLF induced a [Ca2+]j increase in a concentration-dependent manner, showing maximal activity at approximately 10−4 mm. The 10−3 mm fMLF did not affect [Ca2+] in CD133 + cells, suggesting FPR on CD133+ cells was desensitised by such a high concentration of fMLF, a property also seen in myeloid cells [12]. Interestingly FPR has recently been detected in haematopoietic stem cells and mediates stem cell accumulation at the site of injury to accelerate wound healing [14]. Although the precise role of FPR in CD133+ GSCs has yet to be fully elucidated, our results obtained so far strongly suggest the potential participation of this receptor in the angiogenic process of glioblastoma by its functional expression on GSCs. Thus, GSCs and its FPR should be considered as a molecular target for the development of novel anti-glioma therapies.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mrs Wei Sun and Miss Li-Ting Wang (Central Laboratory, Third Military Medical University, Chongqing, People’s Republic of China) for technical assistance in laser confocal scanning microscopy. This project was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Programme of China (973 Project, No. 2006CB708503) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, No. 30670804).

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest were declared.

References

- 1.Galli R, Binda E, Orfaneli U. Isolation and characterization of tumorigenic, stem-like neural precursors from human glioblastoma. Cancer Res 2004;64:7011–7012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hemandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:3983–3988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh SK, Clarke ID, Hide T, Dirks PB. Cancer stem cells in nervous system tumors. Oncogene 2004;23:7267–7273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dean M, Fojo T, Bates S. Tumour stem cells and drug resistance. Nature 2005;5:275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blair A, Hogge DE, Allies LE, Lansdorp PM, Sutherland HJ. Lack of expression of Thy-1 (CD90) on acute myeloid leukemia cells with long-term proliferative ability in vitro and in vivo. Blood 1997;89:3104–3112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med 1997;3:730–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID. Identification of human brain tumor initiating cells. Nature 2004;432:396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mizrak D, Brittan M, Alison MR. CD133: molecule of the moment. J Pathol 2008;214:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kondo T, Setoguchi T, Taga T. Persistence of a small subpopulation of cancer stem-like cells in the C6 glioma cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:781–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bao S, Wu QL, Sathomsumetee S, Hao YL, Li ZZ, Hjelmeland AB, et al. Stem cell-like glioma cells promote tumor angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res 2006;66:7843–7848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou Y, Bian X, Le Y, Gong W, Hu J, Zhang X, et al. Formylpeptide receptor FPR and the rapid growth of magligant human glioma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:823–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Y, Murphy PM, Wang JM. Formyl-peptide receptors revisited. Trends Immunol 2002;23:541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao XH, Ping YF, Chen JH, Chen DL, Xu CP, Zheng J, et al. Production of angiogenic factors by human glioblastoma cells following activation of the G-protein coupled formylpeptide receptor FPR. J Neurooncol 2007;86:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viswanathan A, Painter RG, Lanson NA Jr, Wang G. Functional expression of N-formyl peptide receptors in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell. Stem Cells 2007;25:1263–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lapidot T, Pflumio F, Doedens M, Murdoch B, Williams DE, Dick JE. Cytokine stimulation of multilineage hematopoiesis from immature human cells engrafted in SCID mice. Science 1992;255:1137–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoang T, Caceres-Cortes J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature 1994;367:645–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hope KJ, Jin L, Dick JE. Acute myeloid leukemia originates from a hierarchy of leukemic stem cell classes that differ in self-renewal capacity. Nat Immunol 2004;5:738–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatia M AC133 expression in human stem cells. Leukemia 2001;15:1685–1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz PH, Bryant PJ, Fuja TJ, Su H, O’Dowd DK, Klassen H. Isolation and characterization of neural progenitor cells from postmortem human cortex. J Neurosci Res 2003;74:838–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee A, Kessler JD, Read TA, Kaiser C, Corbeil D, Huttner WB, et al. Isolation of neural stem cells from the postnatal cerebellum. Nat Neurosci 2005;8:723–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor MD, Poppleton H, Fuller C, Su X, Liu Y, Jensen P, et al. Radial glia cells are candidate stem cells of ependymoma. Cancer Cell 2005;8:323–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folkman J Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. Semin Oncol 2002;29:15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunn IF, Heese O, Black PM. Growth factors in glioma angiogenesis: FGFs, PDGF, EGF, and TGFs. J Neurooncol 2000;50:121–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leon SP, Folkerth RD, Black PM. Microvessel density is a prognostic indicator for patients with astroglial brain tumor. Cancer (Philadelphia) 1996;77:362–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischer I, Gagner JP, Law M, Newcomb EW, Zagzag D. Angiogenesis in gliomas: biology and molecular pathophysiology. Brain Pathol 2005;15:297–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nabors LB, Suswam E, Huang YY, Yang X, Johnson MJ, King PH, et al. Tumor necrosis factor a induces angiogenic factor up-regulation in malignant glioma cells: a role for RNA stabilization and HuR. Cancer Res 2003;63:4148–4187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gagner JP, Law M, Fischer I, Newcomb EW, Zagzag D. Angiogenesis in glioma: imaging and experimental therapeutics. Brain Pathol 2005;15:342–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bian XW, Jiang XF, Chen JH, Bai JS, Dai C, Wang QL, et al. Increased angiogenic capabilities of endothelial cells from microvessels of malignant human gliomas. Int Immunopharmacol 2006;6:90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]