Abstract

Background

Culturally responsive, strengths-based early-intervention mental health treatment programs are considered most appropriate to influence the high rates of psychological distress and suicide experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth. Few early intervention services effectively bridge the socio-cultural and geographic challenges of providing sufficient and culturally relevant services in rural and remote Australia. Mental Health apps provide an opportunity to bridge current gaps in service access if co-designed with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth to meet their needs.

Aims

This paper reports the results of the formative stage of the AIMhi-Y App development process which engaged Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth in the co-design of the new culturally informed AIMhi-Y App.

Methods

Using a participatory design research approach, a series of co-design workshops were held across three sites with five groups of young people. Workshops explored concepts, understanding, language, acceptability of electronic mental health tools (e-mental health) and identified important characteristics of the presented applications and websites, chosen for relevance to this group. An additional peer supported online survey explored use of technology, help seeking and e-mental health design elements which contribute to acceptability.

Results

Forty-five, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth, aged 10–18 years, from three sites in the Northern Territory (NT) were involved in the workshops (n = 29). Although experiencing psychological distress, participants faced barriers to help seeking. Apps were perceived as a potential solution to overcome barriers by increasing mental health literacy, providing anonymity if desired, and linking young people with further help. Preferred app characteristics included a strength-based approach, mental health information, relatable content and a fun, appealing, easy to use interface which encouraged app progression. Findings informed the new AIMhi-Y App draft, which is a strengths-based early intervention wellbeing app for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth.

Conclusions

Research findings highlight the need, feasibility and potential of these types of tools, from the perspective of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth.

Abbreviations: AIMhi, Aboriginal and Islander Mental Health Initiative; AIMhi-Y, Aboriginal and Islander Mental Health Initiative for youth; e-mental health, electronic mental health; ERG, Expert Reference Group; NT, Northern Territory; RCT, randomized controlled trial; WA, Western Australia

Keywords: mental health, adolescent, culturally appropriate technology, aboriginal, delivery of health care, participatory design

Highlights

-

•

Despite experiencing psychological distress, Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander youth faced barriers to help seeking

-

•

Youth thought mental health apps had the potential to increase mental health literacy and help seeking behaviour

-

•

Preferred app features included a strength-based storytelling approach, relatable content and a fun, easy to use interface

-

•

Findings informed the AIMhi-Y App draft, an early intervention wellbeing app for Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander youth

1. Introduction

1.1. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth mental health and service access and delivery

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of Australia describe strong connection with land, family, culture and community as promoting wellbeing (MacLean et al., 2017; Purdie et al., 2010). Young people who are supported to develop positive self-esteem, self-regulation and prosocial friendships are more likely to experience improved psychosocial functioning, psychological resilience and physical health (Hopkins et al., 2015; Hopkins et al., 2014). Despite many factors which promote resilience, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth continue to face adversity and disadvantage.

A history of national policies resulting in dispossession, dislocation and discrimination of Australia's first people continue to have significant impacts on the development and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people (Blair et al., 2005; Purdie et al., 2010). A 2016 youth mental health survey (15–19 years), identified that 31.6% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander respondents met the criteria for a probable serious mental illness, compared to 22.2% of non-Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander respondents (Yeomans and Christensen, 2017). Furthermore, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people aged 5–17 accounted for 85 of the 317 (26.8%) deaths by suicide (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016), despite making up only 2.8% of the total population (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017). Despite efforts to alleviate stressors and expand services, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander hospitalization rates involving suicidal behaviour have doubled over the past 12 years, with youth aged 10–14 and females experiencing the biggest increase in admission rates (Leckning et al., 2016).

Despite their need, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth do not seek help for mental health concerns as often as their non-Indigenous counterparts (Price and Dalgleish, 2013) and often delay seeking treatment until crisis point (Leckning et al., 2016). Shame, language differences, fear, intergenerational stigma, limited awareness and lack of appropriate and accessible services prevent help-seeking (Price and Dalgleish, 2013; Vicary and Westerman, 2004). Culturally grounded, universal, strengths-based early interventions are recommended with growing evidence of their effectiveness (MacLean et al., 2017; Nagel et al., 2009). Innovative solutions are being sought to overcome geographic and cross-cultural challenges to providing adequate early intervention services.

1.2. Technology as treatment: accessibility and potential

Recently, technology and telecommunications have become more accessible and affordable in regional and remote Australia, resulting in rapid adoption of mobile technologies and offering potential to promote health and wellbeing (Brusse et al., 2014; Kral, 2010). Few evidence based culturally specific e-mental health treatment programs are available for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (Dingwall et al., 2015; Titov et al., 2018); with only one specific for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth (Shand et al., 2013). Given the high rate of technology uptake, the development of culturally responsive e-mental health resources for this population is particularly relevant and timely.

E-mental health resources offer an opportunity to provide structured, accessible, cost-effective, early intervention mental health care, by bridging geographic and sociocultural divides. E-mental health tools have proven effective in treating people experiencing varied illness severity (Andrews et al., 2010; Titov et al., 2010), diagnoses (Andrews et al., 2018; Andrews and Titov, 2010), in culturally diverse populations (Fleming et al., 2012) and with youth (Merry et al., 2012; Richardson et al., 2010). However, despite an increasing number of studies reporting positive results under trial conditions, there is no robust evidence to suggest mental health apps are effective for preadolescents and adolescents (Grist et al., 2017) with issues such as reach, uptake and adherence problematic (March et al., 2019).

1.3. Culturally responsive treatment approaches: Aboriginal and Islander Mental Health Initiative (AIMhi)

The need for age appropriate, culturally grounded mental health interventions for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth is widely reported (Leckning et al., 2016; Purdie et al., 2010; Skerrett et al., 2018). Currently, there is a paucity of high-level evidence which assesses the effectiveness of psychological therapies for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth. To date, two completed Randomised Controlled Trials (RCT) have shown the effectiveness of culturally adapted treatment approaches for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults (Nagel et al., 2009), and youth aged 16 and above (Tighe et al., 2017). Two others are currently underway (Dingwall et al., 2019; Shand et al., 2013).

One of the only rigorously tested psychological interventions designed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people resulted from the Aboriginal and Islander Mental Health Initiative (AIMhi). The AIMhi ‘Stay Strong Plan’, is a brief strengths based motivational care planning therapy, based on low intensity cognitive behavioural therapy and motivational interviewing principles (Nagel and Thompson, 2008). A RCT, completed in 2009, demonstrated the effectiveness of this culturally responsive treatment on reducing psychological distress, substance use and improving self-management following two, one-hour sessions (Nagel et al., 2009). Results were sustained over an 18-month period.

Developed in 2013, based on the ‘Stay Strong Plan’ described above, the ‘Stay Strong App’ is a bright, interactive practitioner supported care planning tool available on tablet devices. Extensive practitioner training in both the ‘Stay Strong Plan’ and ‘Stay Strong App’ have led to the adoption of this approach into national best practice guidelines, service delivery policies and procedures, in both Indigenous and non-Indigenous settings (Australian Government Department of Health, 2011; Australian Psychological Society, 2018; Central Australian Rural Practitioners Association, 2009; Nori et al., 2013). Community and service providers have suggested the Stay Strong App has particular affinity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth (Dingwall et al., 2015; Povey et al., 2016). However, a major limitation of the currently available Stay Strong App is the availability only on a tablet device, with health practitioner support, limiting its reach and applicability as an early intervention tool. This study sought to use a participatory design research approach to understand adaptations which might improve the engagement, reach and acceptability of this resource from the perspective of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth.

1.4. Research aims

Mixed methods within a participatory design research approach were used to draft a new culturally responsive e-mental health resource in collaboration with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth. This study aimed to:

-

1)

Explore the lived experience of mental health and wellbeing with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth in three Top End Northern Territory (NT) settings

-

2)

Examine the characteristics of e-mental health resources that render them acceptable and appropriate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth

-

3)

Draft a culturally responsive e-mental health resource in collaboration with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth participants.

2. Methods

The lived experience of mental health and wellbeing from the perspective of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth as well as the acceptable and appropriate characteristics of e-mental health tools was explored through co-design workshops. A series of co-design cycles were used to analyse, synthesize and integrate young people's preferences and views, in an iterative process (Hagen et al., 2012).

2.1. Research setting & research team

Two schools and a drug rehabilitation service in the NT were the study sites for this project. One school and the drug rehabilitation service are in a regional center in the Top End and the other school is in a very remote region of the NT with no mobile phone coverage, accessible by light aircraft only. Sites were chosen purposively based on access to youth of varied sociodemographic backgrounds and previous relationships developed by the First Author (JP). The drug rehabilitation service was included to capture the views of young people who were not currently engaged with school.

The research team has substantial collective experience working in Aboriginal health research and clinical practice in both mental and primary health care settings. One male (PPJRM) and two female (AMAP, CPS) Senior Indigenous Co-Researchers played an integral role in study design, consent, data collection, analysis and dissemination ensuring the study was informed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives throughout.

An Expert Reference Group (ERG) provided guidance and advice on study procedures including engagement, recruitment, data collection, analysis and drafting of the resource. It included twelve service providers from the mental health, drug and alcohol, child protection, and education sectors, who met quarterly via teleconference. ERG membership (25% Male, 42% Aboriginal), represented most states in Australia.

Ethical approval for the research was obtained from Menzies School of Health Research Human Ethics Committee (HREC 2017–2991), including Indigenous sub-committee and the Northern Territory Department of Education Research Ethics Committee (n = 13,417).

2.2. Recruitment

2.2.1. Co-design workshops and closed social media group

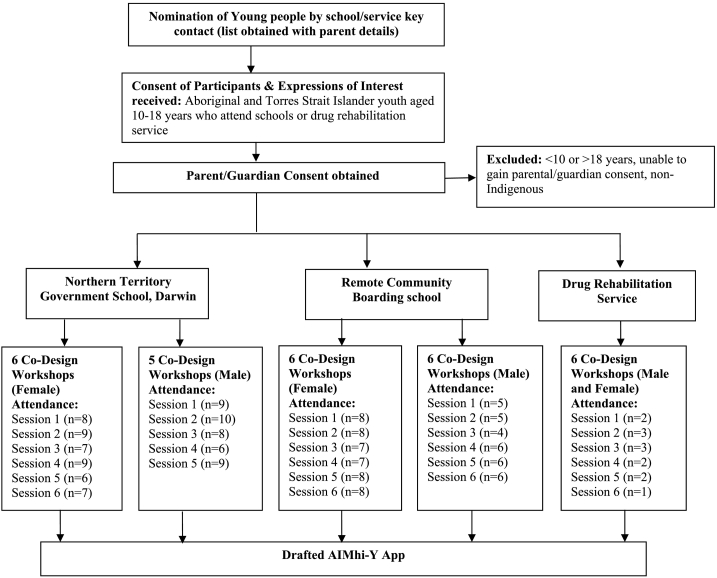

Forty-five participants across three sites were involved in a series of five or six co-design workshops (Fig. 1). Co-design workshop participants were nominated by teaching or other support staff at their site. Inclusion Criteria were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander young people aged 10 to 18 years, identified by a teacher or teachers assistant as able to engage in the co-design workshops and talk in a group setting in English (for Darwin group) and English and Tiwi (for remote group). Participants were excluded if they or their parent/guardian did not consent or withdrew consent. Participants were grouped by gender, and a male and female series of co-design workshops were conducted at each school. A mixed gender group was conducted at the drug rehabilitation center due to small numbers.

Fig. 1.

Provides an overview of study design.

2.3. Data collection methods

Using a participatory design research approach, data collection methods were refined along the way in collaboration with education providers, members of the ERG, Indigenous Research Officers, community elders and participants (Hagen et al., 2012).

2.3.1. Co-design workshops

Co-design workshops sought in-depth understanding of participant experiences and perspectives and allowed the collection of rich and thick data, which is identified by Thabrew et al. (2018) as an essential starting point for the co-design of e-mental health tools. A series of five or six co-design workshops (29 in total) was conducted five times, within two schools and a drug rehabilitation service (see Table 1). The e-mental health tools reviewed are included in Table 2. The first author (JP) or another non-Indigenous Project Officer and a male/female Indigenous Research Officer (CPS, AMAP, PPJRM), who shared the same language background as the participants, facilitated the co-design workshops to ensure cultural safety and enable engagement using participants' first language. A closed Social Media Group complemented each face to face co-design workshop group (5 closed groups in total) and was used to contact participants and disseminate results.

Table 1.

Co-design workshop format.

| Co Design Workshop | Content/Activity |

|---|---|

| One | Identification and discussion of key terms creates common language, assesses mental health literacy, improves understanding of the topic and aims to identify and define the problem. |

| Familiarisation with e-mental health tools generates discussion about design and use of these tools and aims to position and frame the problem and potential solution from the perspective of youth participants. | |

| Two | Vignettes of people with mental health concerns prompts discussion about risk factors, protective factors, help-seeking and beliefs about treatments. |

| Photovoice and video methods invite participants to take photographs/videos of salient issues affecting them and their community (Hergenrather et al., 2009). | |

| Three | Body mapping aims to determine experiences of mental health and wellbeing, map symptoms and identify risk and protective factors. |

| Group discussion of photovoice images and videos from previous week, prompts reflection, shares knowledge and creates critical dialogue (Hergenrather et al., 2009), further defining and positioning the problem. | |

| Familiarisation with e-mental health resources allows participants to identify aspects which enhance or inhibit use, and aims to capture the meaning and common features of an experience | |

| Four | Review and group discussion of e-mental health resources introduced in co-design workshops one and three creates further dialogue about design features which informs the draft of the new resource |

| Online survey collaboratively designed with co-design workshop participants and introduction to peer researcher phase aims to build capacity and involvement of youth in the research process. | |

| Co-Analysis of Body Mapping and/or survey data with participants to highlight similarities and differences | |

| Five | Member-checking of emerging themes allows the identification of commonalities and differences and re-visits topics to deepen understanding. |

| Review and group discussion of first draft of the AIMhi-Y App. Draft presented as a paper-based wireframe with available graphics super imposed. Discussion on content, graphics, usability, and appeal. | |

| Six | Further Member Checking of suggested additions to the drafted app. Further development of specific activities or suggested content. |

| Further review and group discussion of first draft of the AIMhi-Y App. |

Table 2.

E-Mental Health Tools reviewed by participants in Co-design workshops.

| E-mental health resource | Basic Description | Developer & Region involved in development |

|---|---|---|

| Stay Strong App | Therapist supported, strengths based motivational care planning tool, interactive colorful app | Menzies School of Health Research; NT |

| ibobbly App | Self-driven smartphone & tablet suicide prevention app for young people aged 16–35 based on mindfulness and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy principles | Black Dog Institute; Northern WA |

| Yarn Safe Website | Website, information fact sheets on various mental health topics | Headspace; National |

| WICKD Assessment App | Kessler 10, PHQ-9 & EQ5D assessment app, translated into 10 Top End and Central NT Aboriginal Languages | Menzies School of Health Research; NT |

| Proppa Deadly | 1–2 min podcasts from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people across Australia on how they overcame depression or anxiety | Beyond Blue & BIMA Projects Queensland; QLD |

| Italk | Short health promotion cartoons often including NT Aboriginal languages | Italk/Primary Health Network; NT |

| TRAKZ Flipchart | Paper based comic style flipchart teaching positive behavior choices | Menzies School of Health Research; NT |

| AIMhi Yarning about Mental Health Video | 8 min video, providing information on mental health conditions and treatments. | Menzies School of Health Research; NT |

Co-design workshop data was recorded through participant observation, field notes and audio-recording. An iterative process of data analysis, feedback and member checking with participants occurred throughout the series of co-design workshops. Reflexivity and reciprocity were used by researchers within the co-design workshops to improve the rigour of data collection and engagement and trust within the groups (McNair et al., 2008; Togni, 2017).

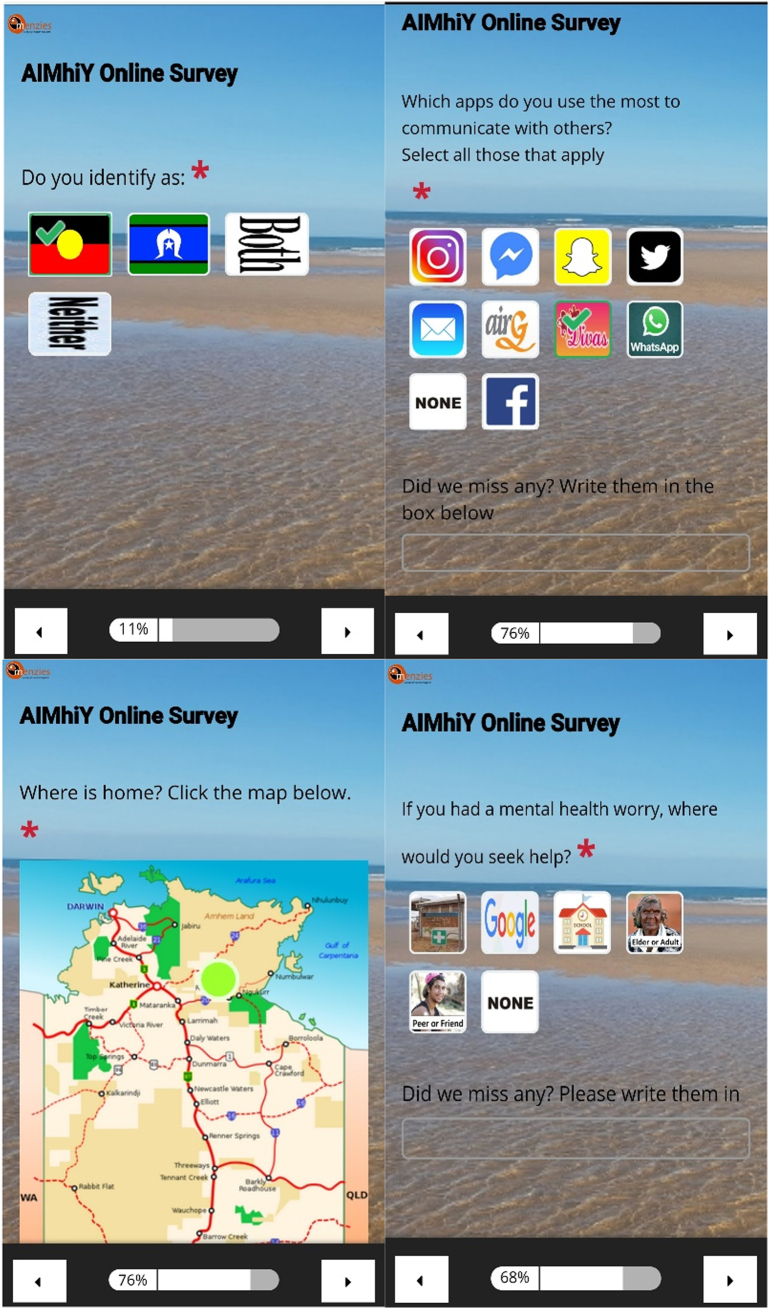

2.3.2. Online survey

A 41-item online survey was collaboratively designed with two groups of co-design workshop participants, the ERG and Indigenous co-researchers to meet the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth (see Fig. 2). It gathered qualitative and quantitative information regarding current use of technology, knowledge of available e-mental health programs and characteristics which affect acceptability of e-mental health resources. The survey used an online survey platform (survey gizmo). Pictorial selection options, drop down boxes, audio recording of each question and two ‘break’ segments were included to enhance usability, promote completion and support those with limited English literacy. Online surveys were distributed through strategies determined by co-design workshop participants, such as social media, email, school and community networks. The opportunity to win one of 35 AU$50 phone credit vouchers encouraged participation in the online survey.

Fig. 2.

Provides a selection of screenshots of Online Survey.

2.3.3. Peer researchers

Peer Researchers (n = 10) of varying ages and communities of origin were invited to borrow a tablet device and facilitate their peers to complete the survey. Brief training was provided to those selected as peer researchers, to ensure confidentiality and safety of survey participants.

2.4. Analysis

Recordings from all twelve remote co-design workshops were collaboratively transcribed and coded by the first author (JP) and Indigenous Co-researchers (AMAP, CPS) allowing verbatim translation from Tiwi to English for all relevant conversations. The remaining seventeen co-design workshop recordings (all in English) were transcribed by the first author (JP). NVIVO Qualitative Data Analysis Software (QSR International) was used for transcription and analysis by the first author (JP). Data from all sources (recordings, survey and participant observation) was independently coded by the first (JP) and second (MS) authors using an inductive thematic approach (Thomas, 2006). When independent analysis was not aligned a process of discussions to achieve consensus was then undertaken. Emerging themes were then discussed and further refined within the research team and ERG. Indigenous Co-researchers (AMAP, CPS, PPJRM) were involved throughout the coding and refining stages, ensuring Aboriginal perspectives informed analysis. Quantitative data was analysed for descriptive statistics using the online survey platform. Survey responses from non-Indigenous people were excluded from analysis. Triangulation through use of multiple sources of data and multiple researcher perspectives informing analysis strengthened the credibility of the results (Fossey et al., 2002).

3. Results

3.1. Participant demographics

3.1.1. Co-design workshops

Forty-five youth engaged in the co-design workshops over a period of 8 months (May–December 2018). Participants were aged 10–18 years, with a minority (7%) who were of school age but not currently engaged in school, while almost one third of participants spoke a language other than English at home (Table 3).

Table 3.

Co-design workshop participant demographics (n = 45).

| Male | 24 (53%) |

| Mean age (range); Standard Deviation | 14.71 (10–18); SD 1.47 |

| Reside in remote community | 24 (53%) |

| English not main language spoken at home | 13 (29%) |

| Not currently engaged in school | 3 (7%) |

| Criminal justice involvement in last 3 months | 2 (4%) |

| Joined social media group | 18 (40%) |

3.1.2. Online survey

Seventy-five Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people participated in the online survey. Participants were majority female, approximately one third spoke a language other than English at home and a proportion (39%) completed the survey within the co-design workshops (Table 4).

Table 4.

Survey participant demographics (n = 75).

| Female | 45 (60%) |

| Aged under 18 | 38 (51%) |

| Reside in NT | 67 (89%) |

| Language spoken at home: | |

| English | 53 (71%) |

| Tiwi | 12 (16%) |

| Yolngu Matha | 2 (3%) |

| Warlpiri | 2 (3%) |

| Ngan'gikurrunggurr | 1 (1%) |

| Other | 5 (7%) |

| Survey completed: | |

| Independently | 34 (45%) |

| Support or research worker facilitated | 8 (11%) |

| Within co-design workshops | 29 (39%) |

| Peer researcher facilitated | 4 (5%) |

| Fully completed survey | 57 (76%) |

3.2. Co-design workshop attendance

Average participant attendance at the co-design workshops was 75% across all groups at the three sites, ranging from 53%–93% for the five groups. Those in the remote school setting were least likely to attend (53% attendance for boys, 70% attendance for girls). This may reflect that participants were asked to attend in their free time (after school) rather than in structured program or school time (as was the case in the other settings). Eleven participants from the urban sites, six from the remote site and two from the drug rehabilitation center registered 100% attendance. Reasons for non-attendance at the groups were; school non-attendance, conflicting school or service activities (such as vocational training, leadership activities or health checks) and not ‘being in the mood’ or ‘feeling like it’ on the day. Indigenous Co-researchers were present at most co-design workshops (21/29; 74%). Importantly the Indigenous Co-researchers were present at all twelve of the remote co-design workshops allowing participants to contribute in their first language.

3.3. Lived experience of mental illness

3.3.1. Protective factors: strengths

Young people were able to confidently identify many things in their lives which help to keep them strong. Researcher observations revealed many were keen learners, asking questions and clarifying their understandings. Many were developing or accomplished artists, writers, leaders and sports people. Table 5 identifies protective factors described by youth in this study.

Table 5.

Protective factors: strengths.

| Sub themes | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|

| Laughing/Humour |

“I just like watching movies, any movies that make me laugh and settle down” “When I have family problems at home, when we all argue over something… [I say] ‘you stay here, I am going [for a] walk’ and I clear my mind out … [then] I just do something really stupid to make them laugh and that tension is just gone…” |

| Going Bush |

“Getting out of the city [will help] - away from all the noise and drama and chaos” “[Bush is] like freedom… Stressors and worries, they will go away quickly if you go out to the bush…” |

| Family and Friends |

“[Friends]… do good things for him, stay a little bit better and stop sniffing [solvents]… at peace, sleep. He is thinking more about family and he is open to them. Here is his mother, his little brother, his grandmother. He is little. They make him feel better because he is happy… he is playing with his little brother, he is at home, he has TV [television], his friends and his little brother…” “Be a friend… if you see them and they are alone, go up and talk to them and don't just walk past them. You could do something with them to take their mind off things… something just like fun. Even just hanging out at home together watching movies…” |

| Keeping active |

“Sport… releases endorphins which make you happy” “Get things off your mind… go for a walk, swimming, exercise, training” |

| Feeling healthy/Looking good |

“… go walk with him, clear his head out… tell him go shower, help him feel better… tell him, do his eyebrows” “When he has improved his appearance, he might feel better about himself… more confident” |

| Help from a trusted person |

“Seek help, talk to someone… [a] professional… teacher… trusted adult… friend” “Take him clinic, get him tablet for his heart and tummy, settle him down” “…if they were hurting themselves, that's when you need to get serious help… Like a trusted adult. Maybe go to a parent…” |

| Good Sleep |

“She needs to go to bed early and not like stay up thinking about it” “Work probably makes him tired so he sleeps better” |

| Medication | “Medication, yeah I think it does [help]. I don't know what is in there, but doctors say that it helps so we follow their orders” “If they are like people who actually need the medication then yeah [it helps]” |

| Future thinking/Positive thinking | “Work your thinking out, like what I am going to do in the future” “…it is good to just isolate yourself, to find yourself, calm yourself and then when you feel alright come back [to the situation]. If you can't change it, then change the way you think about it…” |

| Music and Art |

“It [painting] stops me thinking too much. When I am angry, I come and sit down and paint” “Sometimes when people are angry they listen to music on their phone and go for a walk” |

| Culture |

“Sitting around the fire, tell stories… music… culture dance, go out bush, get the tree and smoking ceremony, healing tree” “Bush tucker, camping, hunting, countryside… yeah all of those songs [traditional music]” |

3.3.2. Precipitating factors: worries

Table 6 identifies the precipitant factors described by youth in this study.

Table 6.

Precipitating factors: Worries.

| Sub themes | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|

| Family worry or conflict |

“Maybe [he is] worrying about family - family worries” “… he is sad, he is in trouble with his family, and he wanted to be alone…” |

| Feeling sad or alone |

“[Depressed is] feeing like you are out of place, alone” “I was upset yesterday - because I was lonely to go back home… [Family] never answer [the phone]. Sometimes my Mum answers, but she tells me to hang up. ‘I am busy I can't talk now’, she always says that to me. It's just them. They won't talk” |

| Fighting, anger & violence |

“He is drinking too much grog [alcohol], getting mad… forgetting about family. [He] starts fighting… picking on other people” “… [She is] not thinking, [she] starts smashing stuff, anything. They might try suicide themselves” “[He] could have bloody knuckles from punching things, getting angry” |

| Drugs, alcohol and sniffing [solvents] |

“… especially drinking [alcohol] and drugs and stuff… it's really common” “When everyone gets stressed out, they have gunja [cannabis] and cigarettes” “… when he is not high… he is going to be mad and angry… more irritated than he was before” |

| Sleep worry | “He has sore eyes from no sleep, red eyes… [he] dosen't go [to] sleep, he says up all night” |

| Money & Food Worry |

“[He is stressing because, he has] no family, no house, no food” “Mum and Dad, they fight a lot, they blame me, steal money for grog [alcohol] and gambling” |

| Housing worry | “I didn't like the way my Auntie's mother spoke to me, I got mad. I got locked out of the house at night. I felt shame, I ran away. Now Aunty says she can't have me, I'm ‘too much trouble’, she can't handle me” |

| Trouble with justice system |

“[It's the] first time I will be free from goal, Mum & child safety” “… I got bail out here, if I do anything bad they will call the cops [police] on me and I will get arrested” |

| Shame |

“… they might feel shame, to just jump up and search it [mental health conditions]” “…you get jealous, you fight someone and family gets involved and especially if there are other families it gets shame” |

| Missing culture/country | “... here I am missing culture… I like family and friends there, good friends, big family and culture and hunting and fishing” |

| Stressing |

“[His] hands, get sweaty and clammy… [he feels] antisocial… fragile temper… mood swings… stress eating or not eating” “[He is] shaking, angry, stressing, breathless… crying… butterflies [in his tummy]… hasn't eaten, hungry… frightened, scared” |

| Body image | “… seeing like body images, getting self-conscious” |

| Overwhelming thoughts |

“[You] shut down, act out… over think it” “…people [are] looking at him, [he is] getting horrors, wrong thinking - like jealousy” |

| Unhealthy lifestyle | “Make him play sport, make him eat healthy” “[If you eat] MacDonald's, all the preservatives… You get fat and become bullied, become lazy, sugar levels get high, feel sick…” |

| Medication worries | “They might be like freakin’ out if they don't have their medication…” |

| Racism | “[He is angry because] maybe they [are] racist” |

| Relationship problems |

“[He has a] broken heart… he just got dumped - girlfriend problems” “… girls get jealous and start fights, yeah that is like most of the fights I have had…” |

| Teasing/Gossip |

“… they [are] throwing a ball at him, the kids laughing and staring… like venom, they are staring into him, he needs help” “… a lot of bullying goes on with social media” “Not really strategies [for dealing with online bullying]… Just tell a trusted adult and report it and don't do it to others…” |

| Trauma | “Things have happened in the past which make me feel sad and angry…” |

3.3.3. Experiences of mental health and psychological distress

Psychological distress was a common experience for youth in this study:

“I need help. I have anger issues, stress, anxiety and depression that leads me to suicide. I never tell anybody, it's not their business. I suffer and harm myself when I'm overwhelmed…”

Many participants across all groups, had recently experienced bereavement as a result of death by suicide. During data collection, two young people in these communities but not involved in this study died by suicide, within a fortnight of each other. Many of the young people involved in the co-design workshops, and the Indigenous Co-researchers either knew or were closely related to these young people. One participant in this study expressed current suicidal ideation. Participant safety protocols were followed, which included the provision of immediate safety measures by research team, notification of senior research team members and referral and follow up provided by the nominated school or service contact person.

One participant expressed frustration regarding suicidal behavior:

“they might be a little bit snappy or whitchy… they might not even be in the mood to talk… they can go for a walk and that, but just don't go walk with a bloody rope, don't go kill yourself, you don't need to commit suicide…”

When asked if this type of behaviour was common, several participants noted:

“Yeah... all the time, people always do that, “people don't want me here, alright I might as well die”, that is exactly how they will be, because no one likes them, when they feel threatened, they just go do it”

One of the groups identified the cumulative nature of psychological distress and its impact on behavior:

“[they have been] bullied, [have] a lot going on, maybe they don't feel safe, at home or whatever… sometimes they might be feeling all that stuff now… but maybe they were arguing over one little thing and the thing probably like got really big…”

Three of five groups identified chronic disease, most often kidney disease, as the result of chronic psychological distress and poor lifestyle choices:

“the [kidneys] are getting filled up with anger, they are getting filled up from drinking and smoking, they get clogged up and fail”

A common response from all groups was the inability to explain mental health conditions and find respectful language to communicate with others:

“Sometimes it's hard to explain; sometimes they don't know how they really feel. They feel it but they don't know how to express it”

“Depressed, that's a strong word. I don't know how to explain it. I know what it means but I don't know how to explain it.”

“I said mental. No, a nicer word than that, like special. Like when you are not trying to be mean”

3.3.4. Help seeking: preferences and barriers

The most commonly chosen response for help seeking was “talking to someone you trust” which was most often a parent, peer or trusted adult. If issues were perceived as “serious” (i.e. Suicidal ideation or aggressive behavior), or “out of their hands” then young people also discussed accessing a counselor, “mental health doctor”, Aboriginal Mental Health Worker or the local police or health center. Most participants knew where to seek further help. The local health clinic or Wellbeing Centre (remote) and Headspace (urban) were the most frequently chosen sources for further help. One participant mentioned national helplines such as KidsHelpLine or Lifeline.

Despite experiencing distress, young people identified several barriers to seeking help. Fear, stigma and shame were factors preventing help seeking:

“I think if he is wanting to get help then he will be ok, but if he is not then you can't do anything some people might see it as, if they give in [seek help] and open up they will be seen as weak, like they don't want to because of their pride...”

“I think sometimes it's scary that if you say something someone might get mad at you, opening up makes you vulnerable”

Participants in the urban group identified the limited choices for face to face mental health care compared to other regions of Australia and potential long distances required to travel to access face to face services.

3.4. Technology, e-mental health resources and young people's preferences

3.4.1. Technology use and potential of e-mental health resources

Young people across all groups were technologically competent and were using the internet to source health information:

"I hurt my calf last week and I looked at YouTube on how to stretch it.... you mean like that?"

Participants viewed using mental health apps as a way to anonymously seek help, normalize their experiences and combat feelings of loneliness:

“Apps [can help people understand] it [mental illness] can be like natural and they don't feel like they are the only ones going through that in the world”

“How the person is doing this app… they feel all that bad stuff and they tap on something, like how they feel… [the app should] give a little sign… like a supporting message. ‘Yeah, I been through this too, we will get through this together’.... so that way they don't feel alone”

“Friends, would be good to get help without anyone knowing, sometimes you feel like they don't understand and your being judged”

Apps were viewed as a potential “pathway to help” by giving young people “the words they need” and the ability to “show how you have been feeling without talking, because you might forget or not want to talk about it”:

“I think sitting down with someone would be kind [of] daunting, so if at the beginning you could do it on your own and it gets sent away to a counselor… and then they can review it and send it back”

The majority of participants thought these tools would be most appropriate “for people who… need help” or “those who are stressing with life” however the possibility of using these tools as a preventative measure was highlighted:

“Everyone [should use the app], because it can be used as like help, but it can be used as a preventative thing as well... like if you are focusing on the positives once a week”

There was some concern that e-mental health tools might be less suitable for those with severe illness:

“… some people might be like really sad to a point where an app can't help them so they might need to go see a person…”

3.4.2. Important characteristics of e-Mental Health resources

Table 7 highlights important characteristics of e-mental health resources, which have been grouped under three major themes; factors which engage, sustain and support.

Table 7.

Valued characteristics of e-mental health resources.

| Themes & Subthemes | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|

| ENGAGE: FEATURES THAT GET THEM INTERESTED | |

| Humor & fun |

“Play music, make it fun at the start” “[Include some] funny videos, you find them everywhere, like funny cat videos” “I feel like the apps… like graphics and stuff, [are] not really catching our attention properly... If I were to use the app, I… want something that would keep me interested, like want to keep using it… Bright colours, graphics… like a game…” |

| Music & sounds |

“… I like the music behind them, it wasn’t just them talking, it makes it more interesting, keeps you interested” “[Add some] cute little sound[s] like ‘ding’… [to] keep encouraging you do to things in the app” “Bubbles… [they] would have to be with the pop sound… like "pop" "pop"… [add some] catchy background music…” |

| Vibrant colours |

“…it had the feeling that you picked before, and the colour of it and you could change it so you could see how the colour impacted it... I made it a pink colour and it didn’t look as bad as before in like a blue....” “There is a lot of red and orange, change that to bright colours… colour is a big one” |

| Relatable images, voices, language and stories |

“[I relate to the] backgrounds, videos, what they were talking about, like going to country and stuff, [the] language used” “… some people might feel uncomfortable if it is a guy… you know for Lore, you feel better if it’s a girl talking to you” “Some kids might not be from here... I feel weird looking at that [desert imagery] because I am from an Island” “Some of the stories are weird, like when he missed a goal and then… all this started about him running over a baby… they are good stories but they are a little unrealistic” |

| Stories about positive change, which offer support, helpful tips and information |

“… [include] situations that can happen in your life, different stories, which you can relate to, and in the end they got help and you might think… oh I will go and get help too” “[Include] like a fake story, but make it believeable.… [the app could give the user] a supporting message, yeah “I have been through this too, we will get through this together”. So that way they don’t feel alone” |

| Characters, including teenagers, other family and role models |

“You could have… like mob [Aboriginal people] who have gone through all this stuff, so get someone that is around their age to talk, so they know I am not the only one going through this…” “[Young people will] stand up and listen [if spoken by an Elder]” “[Include role models but] not famous people… like normal role models; footy people and stuff and people who can help” |

| Metaphors |

“It was about your thoughts and how your thoughts are like the seasons... the wet season is the hard times and the dry is the good times... and it cycles. At first, I didn’t understand it but then I did. I was just being stupid. It was like a random analogy but then it made sense, when they explained it…” “The leaves grow... when you have good things... the tree is you... and the leaves die and that means bad” |

| SUSTAIN: FACTORS THAT KEEP THEM INTERESTED | |

| Options for customisation & personalisation |

“Those options are cool [changing colour schemes]… when you can personalise it” “I like how it is your profile, you make it for yourself, so the person using the app knows it belongs to them… they feel like they own it” |

| Information followed by interactive activities |

“… if it [app] shows you how to prevent all that from happening, like information” “[I like that the] video introduces the topic and activity gives you something to do” “… if they just have to read and take pictures, they will get bored… but if they are touching it… if they are more hands on they will feel more a part of it” |

| Exploration component |

“[I like] it [site map of ibobbly app] shows you all the different things you can do in the app and how it can help...” “[I like that] you could choose if it was a good way to go or a bad way to go.... and if you choose the bad one... it gives you advice on why you shouldn’t and which way is a better way to go” |

| Challenges, rewards and records of progress over time | “…once you have achieved a few [goals] and you can look back at them; it’s a good thing for your confidence…” “Each time you complete your goal it comes up with a little medal, or medallion.... you could have a trophy case, where you could display all the things you have achieved, the goals you have completed…” “If we had a game… you have to be able to level up and get bonus points, then it makes it harder…there has to be a goal” |

| Options for sharing | “Wouldn't it be cool if you could share or see… what other people put in that part… post their positive things, you wouldn't be able to see the rest of it… they can get things… to make them[selves] happier, from what other people have done” |

| Reminders | “Maybe once a week [send a notification], but only once, don’t send like 100 notifications, or people will turn them off” |

| SUPPORT: FACTORS THAT FACILITATE ACCESS, HELPSEEKING & SAFETY | |

| Designs that overcome access challenges |

“It would be pretty cool if it was on your own phone… if you were stressed or depressed you would use it more” “Do[ing] it on your own phone feels more personal” “[Most people own a phone]… but might not have internet [data credit]… maybe that should be part of the app, sometimes you need the internet to access things but sometimes you don't…” “It was weird, we had two videos playing at the same time, it was so confusing” “Frustrating for some people when it is lagging because they might not have fast phones and stuff” |

| Effective communication |

“…have people talking, like speaker... it’s better that way, some people can’t even read…” “… her idea is pretty good… click on the next one [symbol of symptoms]… and then you could put it [symbol] up there, like maybe make it shrink a bit, then you can drag it onto the person – [i.e include intuitive symbols]” “I don’t know what it is called [app] we just look at the picture [icon], and we just click it” |

| Ease of use | “…it was too much, there was a lot of options, too much to go through, the videos are the main stuff” |

| Options for users to seek further help |

“You are not going to get an answer for everything [from the app], you might need to get more personalised help… that is where you need to have the help contacts” “…[I like that the app had] all the family members, and doctors and stuff, the people that are closest to you, and the people on the outside you can talk to as well” |

| Security features as an option |

“Where is this [app information] going? Who is going to see it, it’s not something I would like to share with everyone” “[You need a password, because] it is different to that stuff [Social Media]… that actually means something…” “[Apps that you] don’t need to login or register” |

3.5. Online survey results

Results show; high rates of smartphone ownership and knowledge of app download; limited access to internet credit; lower rates of tablet use (Table 8); a trend to increased use of Facebook with age; with younger people more likely to use Snapchat and Instagram and high ambivalence about seeking mental health help online, particularly for those in younger age groups (Table 9).

Table 8.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander respondent's phone ownership and usage by age.

| All Responses (n = 67a/73b) |

10–14 years (n = 26a/28b) |

15–26 years (n = 16a/18b) |

27+ years (n = 25a/27b) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Own smartphone | 66/73 (90%) | 25/28 (90%) | 16/18 (89%) | 25/27 (93%) |

| Own tablet device | 31/73 (43%) | 9/28 (32%) | 7/18 (39%) | 15/27 (56%) |

| Use others phone/tablet daily | 15/69 (22%) | 10/28 (35%) | 3/18 (16%) | 2/26 (7%) |

| Use internet daily | 34/69 (49%) | 12/28 (42%) | 7/18 (38%) | 15/26 (57%) |

| Credit for internet today | 38/67 (57%) | 12/26 (46%) | 11/16 (69%) | 15/25 (60%) |

| Credit for phone today | 42/67 (63%) | 13/26 (50%) | 9/16 (56%) | 20/25 (80%) |

| Can download an app | 58/67 (87%) | 21/26 (81%) | 16/16 (100%) | 21/25 (84%) |

Complete responses.

Partial responses.

Table 9.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander respondent's app usage, help seeking and preferred characteristics by age.

| All responses (n = 57a/64b) |

10–14 years (n = 22a/24b) |

15–26 years (n = 14a/16b) |

27+ years (n = 21a/24b) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| App use: communication | Facebook (39/64; 61%) Messenger (34/64; 53%) Instagram (32/64; 50%) |

Instagram (17/24; 71%) Snapchat (16/24; 67%) Messenger (10/24; 42%) |

Instagram (11/16; 69%) Messenger (11/16; 69%) Facebook (11/16; 69%) |

Facebook (19/24; 79%) Messenger (13/24; 54%) Email (11/24; 46%) |

| App use: health information | Google (49/64; 77%) YouTube (14/64; 22%) None (9/64; 14%) |

Google (19/24; 79%) You Tube (8/24; 33%) Health Apps (4/24; 17%) |

Google (12/16; 75%) YouTube (4/16; 25%) None (3/16; 19%) |

Google (18/24; 75%) Facebook (4/24; 17%) None (4/24; 17%) |

| Enjoyable attributes | Connect with others (41/62; 66%) Relaxation/Fun (32/62; 51%) Learn (26/62; 42%) |

Connect with others (14/24; 58%) Relaxation/Fun (13/24; 54%) Relieve boredom (10/24; 42%) |

Connect with others (10/15; 67%) Relaxation/Fun (8/15; 53%) Relieve boredom (7/15; 47%) |

Connect with others (17/23; 74%) Learn (12/23; 52%) Relaxation/Fun (11/23; 48%) |

| Seek health help? | Clinic (38/58; 66%) Elder Adult (24/58; 41%) Google (21/58; 36%) |

Elder Adult (15/23; 65%) Clinic (12/23; 52%) Peer/Friend (11/23; 47%) |

Clinic (9/13; 69%) Google (9/13; 69%) Peer/Friend (4/13; 31%) Elder Adult (4/13; 31%) |

Clinic (17/22; 77%) Google (8/22; 36%) Elder/Adult (5/22; 23%) |

| Seek mental health help? | Clinic (35/59; 59%) Elder/Adult (29/59; 49%) Peer/Friend (25/59; 42%) Google (15/59; 25%) |

Elder/Adult (16/23; 70%) Peer/Friend (12/23; 52%) Clinic (10/23; 43%) |

Clinic (10/14; 71%) Elder/Adult (6/14; 43%) Peer/Friend (5/14; 36%) School (5/14; 36%) Google (5/14; 36%) |

Clinic (15/22; 68%) Peer Friend (8/22; 37%) Elder/Adult (7/22; 32%) |

| Seek online mental health help? | Yes (26/57; 46%) No (9/57; 16%) Maybe (22/57; 39%) |

Yes (9/23; 39%) No (4/23; 17%) Maybe (10/23; 44%) |

Yes (5/13; 39%) No (2/13; 15%) Maybe (6/13; 46%) |

Yes (12/21; 57%) No (3/21; 29%) Maybe (6/21; 29%) |

| Preferred app features | Easy to use (40/57; 70%) Relatable imagery (39/57; 68%) Information (36/57; 63%) |

Easy to use (15/22; 68%) Relatable imagery (15/22; 68%) Information (11/22; 50%) |

Easy to use (10/14; 71%) Relatable imagery (10/14; 71%) Information (10/14; 71%) |

Easy to use (15/21; 71%) Relatable imagery (14/21; 67%) Information (14/21; 67%) Skill development (14/21; 67%) |

Complete responses.

Partial responses.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key findings

In line with previous findings young people in this study identified many factors that promote wellbeing for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth, such as family, culture and physical health (MacLean et al., 2017; Purdie et al., 2010). Our findings also highlight the prevalence of psychological distress and precipitating factors of mental illness, within the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth population in the NT and adds the voices of youth to this discussion. It brings awareness of the optimism of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth regarding e-mental health resources and their preferred content and design characteristics for these tools.

Many participants were experiencing psychological distress and negative influences on their mental health and wellbeing. This is not unexpected given the high rates of psychological distress and related precipitants reported within this population (Dray et al., 2016). Young people's concern and exposure to suicidal behavior within the community was revealed by the frequency of suicidal ideation, bereavement due to suicide and feelings of frustration regarding suicidal behavior. The resulting trauma, vigilance and bereavement surrounding suicides is of concern, factors which others have identified (Yeomans and Christensen, 2017). This is likely to reflect the experiences of many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth and communities around Australia, where youth suicide rates are significantly higher than in non-Indigenous communities (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016). This highlights the need for appropriate support measures and strengths based early intervention approaches for individuals and communities.

For some, basic needs, like food security, personal safety and housing continue to be challenges, as others have recently reported (Lowell et al., 2018). Furthermore, despite being more technologically connected than ever before, feelings of loneliness are a concern for young people, suggesting that the connection to others online is insufficient to overcome this challenge. New anxieties, such as cyberbullying have also arisen, with young people vulnerable and ill equipped to mitigate these challenges. This confirms the need for culturally specific anti cyberbullying campaigns, as identified by Kral (2014).

All participants involved in the co-design workshops generally sought help for mental health concerns from peers, parents and trusted adults rather than through formal treatment settings. This is consistent across other youth population groups in Australia (Yeomans and Christensen, 2017) and has led to a focus on upskilling ‘natural helpers’ in communities, such as peers, parents, teachers and other support people. The potential of e-mental health approaches to complement both formal and informal face to face support is promising. It is however, also vitally important that both ‘natural helpers’ and formal mental health support systems, continue to become more robust to meet this growing need.

In line with previous findings, young people identified fear, shame, stigma, limited awareness, limited choices for face to face care and long distances, as barriers to accessing mental health care (Price and Dalgleish, 2013). Although these findings are similar to non-Indigenous young people's experiences (Gulliver et al., 2010), they are often magnified in Indigenous contexts due to the effects of intergenerational trauma, discrimination, cultural belief and language differences and geographically remote communities (Isaacs et al., 2010; Price and Dalgleish, 2013). However, a difference in help seeking between our study population and others was identified. People within this study aged 15 to 26 years, who responded to the online survey, most often identified a ‘clinic’ or health center as the place (71%) they would seek help for mental health concerns. This is inconsistent with others findings who report a much lower tendency to access formal mental health supports (Price and Dalgleish, 2013; Yeomans and Christensen, 2017). This finding was however, consistent with the co-design workshop participants views, when they rated the concern as ‘serious’ or ‘out of their hands’ (i.e. suicidal or aggressive behavior). We suspect this finding reflects the experience of delayed help seeking reported in this population, which contributes to heightened crisis presentations & completed suicides (Leckning et al., 2016). This may be due to cultural beliefs and understandings of mental health concerns, as previously described by Vicary and Westerman (2004) and Ypinazar et al. (2007), confirming the need for culturally specific mental health approaches. These findings highlight the additional barriers Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people face when accessing mental health care and strengthens the evidence for culturally relevant awareness campaigns targeting early intervention and help seeking.

Young people in this study were highly connected with technology, and smartphone ownership was higher (90%) than currently available estimations of ownership (McNair Innovations, 2016). Participants were technologically competent, using technology for communication, learning, relaxation and to relieve boredom, similar to findings by Kral (2014). This study has also identified that young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are using the internet to access health information. However, a large proportion (44–46%) are ambivalent or skeptical about accessing mental health information online. This study did not examine underlying reasons for these views but others have suggested stigma, limited mental health literacy and concern about quality of the information are potential reasons (Christensen et al., 2011; Gulliver et al., 2010; Povey et al., 2016). This ambivalence presents an opportunity for the promotion of high quality, trusted resources which are tailored to youth perspectives. It also highlights the importance of promoting access to quality e-mental health assessment strategies such as the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS) tool (Stoyanov et al., 2016).

Participants highlighted the potential of e-mental health apps to: provide information, support the development of respectful language, combat stigma and improve help seeking. Mental health literacy contributes to the early identification and intervention for mental health concerns in childhood and adolescence and can positively impact the trajectory, including duration and severity of mental illness throughout life (Kelly et al., 2007).

Young people valued e-mental health tools which were fun, easy to use, relatable and provided mental health information through storytelling. There were differences in preferences between age, gender and language backgrounds. Younger people preferred fun and engaging activities and older adolescents preferred mental health information, while females preferred a range of engaging activities and options for customisation and males preferred “not too much”. This is similar to the findings by Fleming et al. (2019) and Orji et al. (2017) who identified preference patterns among e-mental health users. Understanding these differences is particularly useful in tailoring and targeting e-mental health interventions to suit the needs of youth across the fast-changing period of adolescence.

There is increasing evidence of acceptability of e-mental health resources among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Their ability to; provide information, accessible & anonymous treatment, complement face-to-face interventions and offer universal early intervention is becoming established (Bennett-Levy et al., 2017; Dingwall et al., 2015; Povey et al., 2016), with evidence on effectiveness starting to emerge (Dingwall et al., 2019; Shand et al., 2013). Co-design is likely to enhance the acceptability of e-mental health interventions, however there remains a lack of theory based design, in depth reporting and process evaluation reported in the literature (Mirkovic et al., 2018; Orlowski et al., 2015).

This study shows that young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are enthusiastic about e-mental health tools designed to meet their needs and can assist in integrating their preferences into new resources. This formative project has resulted in the first draft of a mental health and wellbeing app, the AIMhi-Y App, which incorporates the perspectives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth, in regional and remote NT. This collaboration is recognised as an essential element of the Participatory Design Research approach (Hagen et al., 2012).

The resulting prototype (storyboard with script) is currently under development with Phase Two of co-design completed in 2019. This additional phase of co-design aims to refine prototypes with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth, and include mental health specialists, service providers, e-mental health specialists and a digital agency in the co-design process. This will ensure the final product is fit for purpose within this setting. The smartphone compatible, self-driven early intervention focus of this prototype overcomes the limitations of reach and accessibility of the currently available Stay Strong App described above. Pilot testing phases begin in 2020, with a RCT testing the effectiveness of the app in improving wellbeing planned for 2021.

4.2. Limitations

One of the challenges of effective co-design is selection bias, with the inclusion of youth in the co-design process who are engaged and generally functioning well in their school and community (Thabrew et al., 2018). This misrepresents the needs and desires of those who are disengaged and have the potential to benefit most from these types of tools (Thabrew et al., 2018). Although that is to some extent the case in this study, we also made effort to include those who were disengaged from school resulting in a wide range of participants from varying age groups, socioeconomic circumstances, geographical locations and language backgrounds. In doing so, we hope that the developed app will be relevant and appealing to a wide variety of young people.

The online survey sample size was small with only 75 responses received. A percentage (39%) of these responses were completed as part of our co-design workshop groups. This triangulation strengthens the findings of the qualitative data for this group but is not generalizable to other groups across Australia.

5. Conclusions

Young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are embracing technology and see the potential of e-mental health resources. It is important that tools with appropriate content, which are safe, relatable, informative and engaging are developed. If apps are designed to meet the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth and supported within existing service structures, youth are much more likely to use these tools.

Multi-sectorial action is required to adequately support the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth. Safe affordable housing, community led suicide prevention programs and the upskilling and support of ‘natural helpers’ are just some potential avenues identified within this study. E-mental health programs have potential to form part of the solution to improving the mental health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all the young people, parents, teachers, support people and members of our ERG who made this research possible. Tiwi Land Council provided approval for this project to occur. Funding was provided by Channel 7 Children's Research Foundation, South Australia [reference number 181700]. The first author (JP) was supported by Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship and an Austrailan Rotarty Health, Ian Scott Scholarship.

References

- Andrews G., Titov N. Treating people you never see: Internet-based treatment of the internalising mental disorders. Aust. Health Rev. 2010;34:144–147. doi: 10.1071/ah09775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G., Cuijpers P., Craske M., McEvoy P., Titov N. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G., Basu A., Cuijpers P., Craske M., McEvoy P., English C., Newby J. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: An updated meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2018;55:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics Intentional self-harm in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. 2016. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/3303.0~2015~Main%20Features~Intentional%20self-harm%20in%20Aboriginal%20and%20Torres%20Strait%20Islander%20people~9

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016 Census shows growing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population. 2017. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/MediaRealesesByCatalogue/02D50FAA9987D6B7CA25814800087E03?OpenDocument

- Australian Government Department of Health Alcohol treatment guidelines for indigenous Australians. 2011. http://webarchive.nla.gov.au/gov/20140802004158/http://www.alcohol.gov.au/internet/alcohol/publishing.nsf/Content/AGI02

- Australian Psychological Society Social and emotional wellbeing and mental health services in aboriginal Australia. 2018. http://www.sewbmh.org.au/page/3675

- Bennett-Levy J., Singer J., DuBois S., Hyde K. Translating e-mental health into practice: what are the barriers and enablers to e-mental health implementation by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health professionals? J. Med. Internet Res. 2017;19(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.6269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair E.M., Zubrick S.R., Cox A.H. The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: findings to date on adolescents. Med. J. Aust. 2005;183(8):433–435. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb07112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusse C., Gardner K., McAullay D., Dowden M. Social media and mobile apps for health promotion in Australian indigenous populations: scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014;16(12):e280. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Australian Rural Practitioners Association . 5th Edition edn. Centre for Remote Health; 2009. CARPA Standard Treatment Manual, by Central Australian Rural Practitioners Association. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H., Reynolds J., Griffiths K. The use of e-health applications for anxiety and depression in young people: Challenges and solutions. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2011;5:58–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2010.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwall K., Puszka S., Sweet M., Nagel T. “Like drawing into sand”: acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness of a new e-mental health resource for service providers working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander people. Aust. Psychol. 2015;50(1):60–69. doi: 10.1111/ap.12100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwall K., Nagel T., Hughes J., Kavanagh D., Cass A., Howard K., Sweet M., Brown S., Sajiv C., Majoni S. Wellbeing intervention for chronic kidney disease (WICKD): a randomised controlled trial study protocol. BMC Psychol. 2019;7(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s40359-018-0264-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dray J., Bowman J., Freund M., Campbell E., Hodder R.K., Lecathelinais C., Wiggers J. Mental health problems in a regional population of Australian adolescents: association with socio-demographic characteristics. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health. 2016;10(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s13034-016-0120-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming T., Dixon R., Frampton C., Merry S. A pragmatic randomized controlled trial of computerized CBT (SPARX) for symptoms of depression among adolescents excluded from mainstream education. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2012;40(5):1–13. doi: 10.1017/S1352465811000695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming T., Merry S., Stasiak K., Hopkins S., Patolo T., Ruru S., Latu M., Shepherd M., Christie G., Goodyear-Smith F. The importance of user segmentation for designing digital therapy for adolescent mental health: findings from scoping processes. JMIR Ment Health. 2019;6(5) doi: 10.2196/12656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossey E., Harvey C., McDermott F., Davidson L. Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2002;36:717–732. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grist R., Porter J., Stallard P. Mental health mobile apps for preadolescents and adolescents: a systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017;19(5):e176. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver A., Griffiths K., Christensen H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10 doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen P., Collin P., Metcalf A., Nicholas M., Rahilly K., Swainston N. 2012. Participatory Design of Evidence-based Online Youth Mental Health Promotion, Prevention, Early Intervention and Treatment. [Google Scholar]

- Hergenrather K.C., Rhodes S.D., Cowan C.A., Bardhoshi G., Pula S. Photovoice as community-based participatory research: a qualitative review. Am. J. Health Behav. 2009;33(6):686–698. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.33.6.6. (613p) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins K.D., Zubrick S.R., Taylor C.L. Resilience amongst Australian Aboriginal Youth: an ecological analysis of factors associated with psychosocial functioning in high and low family risk contexts. PLoS One. 2014;9(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins K.D., Carrington C.J.S., Taylor C.L., Zubrick S.R. Relationships between psychosocial resilience and physical health status of Western Australian Urban Aboriginal Youth. PLoS One. 2015;10(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs A.N., Pyett P., Oakley-Browne M.A., Gruis H., Waples-Crowe P. Barriers and facilitators to the utilization of adult mental health services by Australia's Indigenous people: seeking a way forward. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2010;19(2):75–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2009.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C.M., Jorm A.F., Wright A. Improving mental health literacy as a strategy to facilitate early intervention for mental disorders. Med. J. Aust. 2007;187(S7):S26–S30. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral I. CfAep Research. 2010. Plugged in: Remote Australian Indigenous youth and digital culture. [Google Scholar]

- Kral I. Shifting perceptions, shifting identities: communication technologies and the altered social, cultural and linguistic ecology in a remote indigenous context. Aus J Anthropol. 2014;25 doi: 10.1111/taja.12087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leckning B.A., Li S.Q., Cunningham T., Guthridge S., Robinson G., Nagel T., Silburn S. Trends in hospital admissions involving suicidal behaviour in the Northern Territory, 2001-2013′. Australas Psychiatry. 2016;24(3):300–304. doi: 10.1177/1039856215608282. (10.1177/1039856216629838) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell A., Maypilama L., Fasoli L., Guyula Y., Guyula A., YunupiLatin Small Letter Engu M., Godwin-Thompson J., Gundjarranbuy R., Armstrong E., Garrutju J., McEldowney R. The ‘invisible homeless’ - challenges faced by families bringing up their children in a remote Australian Aboriginal community. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1) doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6286-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean S., Ritte R., Thorpe A., Ewen S., Arabena K. Health and wellbeing outcomes of programs for Indigenous Australians that include strategies to enable the expression of cultural identities: a systematic review. Aust J Prim Health. 2017;23(4):309–318. doi: 10.1071/py16061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March S., Donovan C.L., Baldwin S., Ford M., Spence S.H. Using stepped-care approaches within internet-based interventions for youth anxiety: Three case studies. Internet Interv. 2019:100281. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2019.100281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair Innovations Indigneous media and communications. 2016. https://mcnair.com.au/wp-content/uploads/Indigenous-Media-Infographic.pdf

- McNair R., Taft A., Hegarty K. Using reflexivity to enhance in-depth interviewing skills for the clinician researcher. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008;8:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merry S., Stasiak K., Shepherd M., Frampton C., Fleming T., Lucassen M. The effectiveness of SPARX, a computerised self help intervention for adolescents seeking help for depression: Randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Br. Med. J. 2012;344 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirkovic J., Jessen S., Kristjansdottir O.B., Krogseth T., Koricho A.T., Ruland C.M. Developing Technology to Mobilize Personal Strengths in People with Chronic Illness: Positive Codesign Approach. JMIR Formativ Res. 2018;2(1) doi: 10.2196/10774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel T., Thompson C. Motivational care planning - self management in Indigenous mental health. Aust. Fam. Physician. 2008;37(12):996–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel T., Robinson G., Condon J., Trauer T. Approach to treatment of mental illness and substance dependence in remote Indigenous communities: results of a mixed methods study. Aust J Rural Health. 2009;17(4):174–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2009.01060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nori A., Piovesan R., O’Connor J., Graham A., Shah S., Rigney D., McMillan M., Brown N. 2013. Y Health – Staying Deadly’: An Aboriginal Youth Focussed Translational Action Research Project. [Google Scholar]

- Orji R., Mandryk R., Vassileva J. Improving the efficacy of games for change using personalization models. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI) 2017;24(5):1–22. doi: 10.1145/3119929. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orlowski S.K., Lawn S., Venning A., Winsall M., Jones G.M., Wyld K., Damarell R.A., Antezana G., Schrader G., Smith D., Collin P., Bidargaddi N. Participatory research as one piece of the puzzle: a systematic review of consumer involvement in design of technology-based youth mental health and well-being interventions. JMIR Human Factors. 2015;2(2) doi: 10.2196/humanfactors.4361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povey J., Mills P., Dingwall K., Lowell A., Singer J., Rotumah D., Bennett-Levy J., Nagel T. Acceptability of mental health apps for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: a qualitative study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016;18(3) doi: 10.2196/jmir.5314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M., Dalgleish J. Help-seeking among indigenous Australian adolescents: exploring attitudes, behaviours and barriers. Youth Studies Australia. 2013;32(1):10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Purdie N., Dudgeon P., Walker R., editors. Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. Commonwealth of Australia; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson L.P., McCauley E., Grossman D.C., McCarty C.A., Richards J., Russo J.E., Rockhill C., Katon W. Evaluation of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):1117–1123. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shand F.L., Ridani R., Tighe J., Christensen H. The effectiveness of a suicide prevention app for indigenous Australian youths: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14(1):396. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerrett D.M., Gibson M., Darwin L., Lewis S., Rallah R., De Leo D. Closing the Gap in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Youth Suicide: A Social–Emotional Wellbeing Service Innovation Project. Aust. Psychol. 2018;53(1):13–22. doi: 10.1111/ap.12277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanov S., Hides L., Kavanagh D., Wilson H. Development and validation of the user version of the mobile application rating scale (uMARS) JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4(2):e72. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.5849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thabrew H., Fleming T., Hetrick S., Merry S. Co-design of eHealth interventions with children and young people. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2018;9(481) doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D.R. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 2006;27(2):237–246. doi: 10.1177/1098214005283748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tighe J., Shand F., Ridani R., Mackinnon A., De La Mata N., Christensen H. Ibobbly mobile health intervention for suicide prevention in Australian Indigenous youth: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Andrews G., Kemp A., Robinson E. Characteristics of adults with anxiety or depression treated at an internet clinic: comparison with a national survey and an outpatient clinic. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):1–5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Dear B., Nielssen O., Staples L., Hadjistavropoulos H., Nugent M., Adlam K., Nordgreen T., Bruvik K.H., Hovland A., Repål A., Mathiasen K., Kraepelien M., Blom K., Svanborg C., Lindefors N., Kaldo V. ICBT in routine care: a descriptive analysis of successful clinics in five countries. Internet Interv. 2018;13:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togni S.J. The Uti Kulintjaku project: the path to clear thinking. An evaluation of an innovative, aboriginal-led approach to developing bi-cultural understanding of mental health and wellbeing. Aust. Psychol. 2017;52(4):268–279. doi: 10.1111/ap.12243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vicary D., Westerman T. That’s just the way he is’: some implications of aboriginal mental health beliefs. Adv. Ment. Health. 2004;3(3):103–112. doi: 10.5172/jamh.3.3.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans C., Christensen H. 2017. Youth Mental Health Report: Youth Survey 2012–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ypinazar V., Margolis S., Haswell-Elkins M., Tsey K. Indigenous Australians’ understandings regarding mental health and disorders. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;41(6):467–478. doi: 10.1080/00048670701332953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]