Abstract

Purpose:

Radiation-induced injury is a well-described toxicity in children receiving radiation therapy for tumors of the central nervous system. Standard therapy has historically consisted primarily of high-dose corticosteroids, which carry significant side effects. Preclinical models suggest that radiation necrosis may be mediated in part through vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) overexpression, providing the rationale for use of VEGF inhibitors in the treatment of CNS radiation necrosis. We present the first prospective experience examining the safety, feasibility, neurologic outcomes, and imaging characteristics of bevacizumab therapy for CNS radiation necrosis in children.

Methods:

Seven patients between 1 and 25 years of age with neurologic deterioration and MRI findings consistent with radiation injury or necrosis were enrolled on an IRB-approved pilot feasibility study. Patients received bevacizumab at a dose of 10 mg/kg intravenously every 2 weeks for up to 6 total doses.

Results:

Five patients (83%) were able to wean off corticosteroid therapy during the study period and 4 patients (57%) demonstrated improvement in serial neurologic exams. All patients demonstrated decrease in T1 weighted post-gadolinium enhancement on MRI, while 5 (71%) showed decrease in FLAIR signal. Four patients developed progressive disease of their underlying tumor during bevacizumab therapy.

Conclusions:

Our experience lends support to the safety and feasibility of bevacizumab administration for the treatment of radiation necrosis for appropriately selected patients within the pediatric population.

Keywords: Bevacizumab, radiation injury, radiation necrosis, pediatric

Introduction

Radiation-induced injury is a well-described toxicity affecting approximately 5% of children receiving radiotherapy for central nervous system (CNS) tumors.1,2 Symptoms of radiation injury can range from nonspecific headaches and personality changes to focal neurological deficits, seizures, and even death.3,4 Diagnosis can be challenging, as the enhancing or necrotic foci seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can often mimic radiographic features of tumor progression.5,6 Preclinical models suggest that radiation injury may be mediated by endothelial cell death and perivascular edema, ischemia, and subsequent necrosis.7–9 High-dose corticosteroids have historically been used to symptomatically alleviate this edema.2,10 There is now recognition that this hypoxic microenvironment induces vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) overexpression, further perpetuating vascular permeability and edema.11 Bevacizumab (Avastin™), a humanized monoclonal antibody against VEGF, has seen increased utilization as a therapy for CNS radiation injury.10,12–14 While data from the adult experience with bevacizumab have expanded,10,15 the pediatric literature remains limited to small, retrospective reports.2,16,17 We present here the first prospective experience examining the feasibility, neurologic outcomes, and imaging characteristics of bevacizumab therapy for CNS radiation injury in children.

Methods

Patients between 1 and 25 years of age were eligible if they had received radiation therapy for a histologically confirmed CNS tumor and developed neurologic deterioration as well as MRI findings determined to be consistent with radiation injury or necrosis by the study radiologist. Steroid administration was permitted at the treating clinician’s discretion. Once enrolled, all patients received bevacizumab at a dose of 10 mg/kg intravenously every 2 weeks for a total of 6 doses (3 doses per cycle). An accrual goal of 10 patients was established. The primary objective of this study was feasibility of drug administration, defined as 7 out of 10 patients successfully receiving at least 5 of the 6 scheduled doses of bevacizumab without increase in serious adverse events attributed to bevacizumab. Secondary objectives were descriptive and included evaluating changes in clinical neurologic symptoms, dose and duration of corticosteroid therapy, neuroimaging as assessed through MRI, and quality of life as assessed by the modified McMaster Health Instrument Scale.18 Contrast-enhanced MRI was performed within 28 days prior to starting treatment and at the completion of each cycle of therapy. All available MRI exams were reviewed by a board-certified pediatric neuroradiologist. The study was approved and continuing approval maintained throughout the study by the institutional review board (IRB). All patients or their parents/legal guardians provided written informed consent for study participation, assent was obtained from patients when appropriate, in accordance with local guidelines.

Results

Seven patients were enrolled on this study. However, the study was closed without enrolling sufficient patients to fulfill the primary outcome measure due to poor accrual. The median age was 11 years (range, 4 – 15 years). Diagnoses included both high-grade tumors (ependymoma, diffuse midline glioma, glioneuronal tumor NOS (WHO grade III)) and unresectable and/or multiply-progressive low-grade tumors (pilocytic astrocytoma, diffuse fibrillary astrocytoma, ganglioglioma). Six patients had received prior systemic therapy with cytotoxic chemotherapy. Five patients (71%) received conventionally fractionated photon radiotherapy (median, 59.4 Gy in 1.8 Gy x 33 fractions), while 2 patients (29%) received hypofractionated photon radiotherapy (25 Gy in 5 Gy x 5 fractions). Median time from completion of radiotherapy to symptomatic presentation was 76 days (range, 21 days – 9 months) (Supplemental Table 1).

Three patients (43%) completed the planned two cycles (six doses) of bevacizumab therapy. Four patients (57%) received one cycle (three doses) of bevacizumab therapy then stopped study therapy due to tumor progression by end of cycle 1 evaluation. No patients stopped therapy or withdrew from study due to adverse events or drug intolerability. Median follow up was 4 months (range, 6 weeks – 21 months).

Six patients were receiving dexamethasone at enrollment. Five (83%) were able to wean off corticosteroids during the study period; the remaining patient tolerated a decrease of corticosteroids until they developed new symptoms due to disease recurrence. Of the 3 patients without disease recurrence, all 3 demonstrated symptomatic improvement by serial neurologic examinations (e.g. resolution of ataxia or cranial nerve deficits). One of 4 patients with tumor progression during study therapy demonstrated transient neurologic improvement. Quality of life as assessed by modified McMaster Health Instrument Scale showed no significant change with study therapy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Response to therapy.

| Stable disease (n=3) | Progressive disease (n=4) | |

|---|---|---|

| Bevacizumab Therapy | ||

| One Cycle (3 doses) | 0 (0%) | 4 (100%) |

| Two Cycles (6 doses) | 3 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| Dexamethasone Dose, Mean | ||

| Pre-treatment | 8 mg / day | 5.25 mg / day |

| Post-treatment | 0 mg / day | 1 mg / day |

| Neurologic Improvement | 3 (100%) | 1 (25%) |

| Radiographic Changes | ||

| Decreased gadolinium enhancement | 3 (100%) | 4 (100%) |

| Decreased FLAIR signal | 3 (100%) | 2 (50%) |

| Decreased tumor size | 3 (100%) | 2 (50%) |

| Modified McMasters, Mean | ||

| Pre-treatment | 13.3 | 15.25 |

| Post-treatment | 12.3 | 17.5 |

Following study therapy, all patients had decreased tumor enhancement in T1 weighted images following gadolinium administration. Five of 7 patients had decreased tumor size following treatment (Figure 1). There was increased intrinsic T1 hyperintensity with corresponding increased susceptibility in 6 of 7 patients, interpreted as age indeterminant blood products versus mineralization (unchanged in one patient). There was increased tumor necrosis (size of cystic non-enhancing portions of the tumor) in 4 of 7 patients.

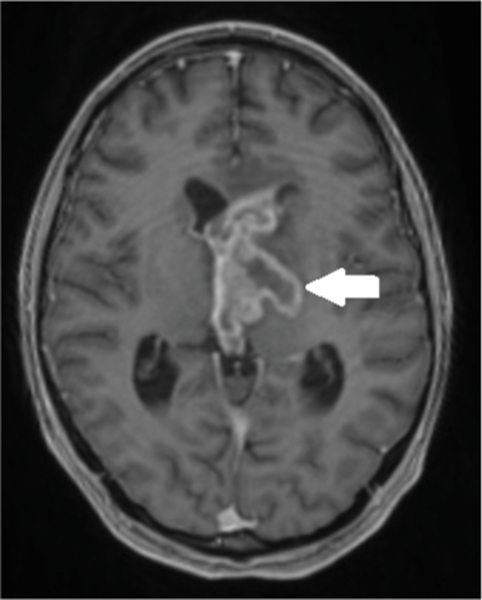

Figure 1a.

Fifteen-year-old boy with bi-thalamic high-grade glioneuronal tumor NOS (WHO grade III). Baseline post gadolinium axial T1 weighted MR image shows a heterogeneously enhancing bi-thalamic mass (arrow) with intraventricular extension and mild ventriculomegaly.

No grade four adverse events (AEs) were reported. There was a single grade 3 upper extremity spasticity attributed to tumor progression. Four patients (57%) experienced grade 1 or 2 AEs deemed possibly, probably, or definitely attributable to the study therapy (Supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

The study ultimately failed to meet the predetermined feasibility criteria, a consequence of both poor accrual and discontinuation due to progressive disease. No patients withdrew from study due to adverse events or drug intolerability. The relatively high proportion of patients in this small cohort who experienced disease progression while on study highlights the diagnostic challenge of discriminating between radiation-induced injury and progressive disease based on MRI findings alone.3,4,19,20 It is possible that patients who eventually exhibited clear progressive disease may have initially been misdiagnosed with radiation-induced injury. Alternatively, as many of the tumors for which radiation therapy is typically reserved in pediatrics are aggressive and carry a poor prognosis, there is a reasonable potential for both radiation injury and progressive disease to be present within a single patient. The strong divergence in objective response seen in the patients with progressive disease may be informative as a clinical rubric. For patients without significant symptomatic improvement on bevacizumab therapy, an alternative or concomitant diagnosis of disease progression should be considered.

Given the limited literature on bevacizumab for the treatment of radiation injury in pediatric patients, clinical practice at many centers is extrapolated from adult data. This study was unable to reach its accrual goals and is limited by the small number of evaluable patients, non-randomized study design, and the heterogeneity in prior chemotherapy regimens, radiation doses, and tumor types. However, the experience represents the largest cohort and first prospective evaluation of bevacizumab therapy for CNS radiation injury in children. Bevacizumab given for radiation necrosis is well tolerated, with few attributable adverse events observed. Most of the patients were able to decrease or stop corticosteroid therapy without corresponding decrease in self-reported quality of life measurements. Similarly, the majority of patients demonstrated objective improvement in both serial neurologic examinations and MRI. Our experience lends support to the safety and feasibility of bevacizumab administration for the treatment of radiation necrosis for appropriately selected patients within the pediatric population.

Supplementary Material

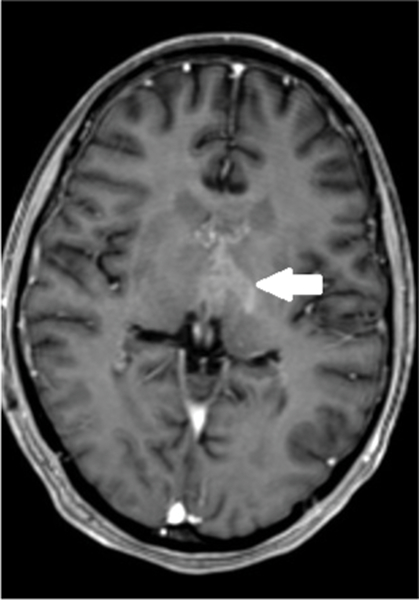

Figure 1b.

Six weeks following treatment, axial T1 weighted MR image shows decreased size and enhancement of the bi-thalamic mass (arrow) as well as decreased lateral ventricular size.

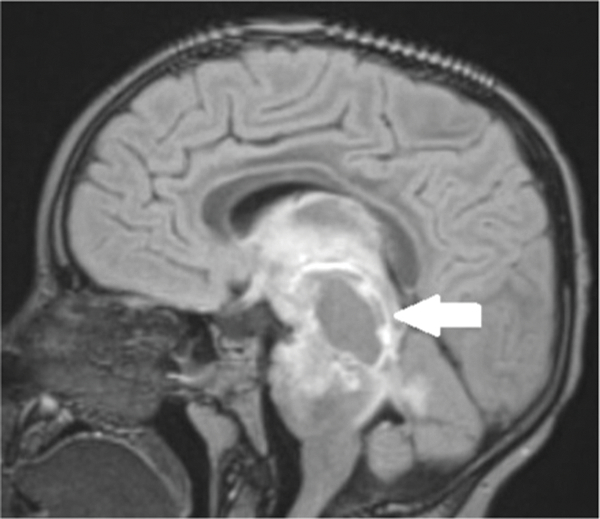

Figure 1c.

Five-year-old boy with diffuse midline glioma. Baseline post-gadolinium sagittal FLAIR MR image shows a heterogeneously enhancing expansile pontine mass (arrow) extending from the thalami superiorly to the pons inferiorly and posteriorly into the superior cerebellar vermis.

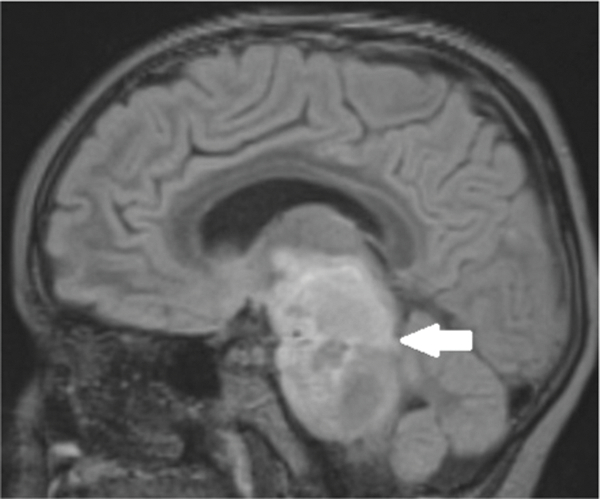

Figure 1d.

Six weeks following treatment, post-gadolinium sagittal FLAIR MR image shows decrease in superior to inferior size of the pontine mass (arrow) as well as decreased enhancement, including the superior cerebellar vermis component.

Acknowledgments:

Support for this study was provided by Genentech, Inc. Genentech US Drug Safety, 1 DNA Way Mailstop 258A, South San Francisco, CA 94080.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there are no additional conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Plimpton SR, Stence N, Hemenway M, Hankinson TC, Foreman N, Liu AK. Cerebral radiation necrosis in pediatric patients. Pediatric hematology and oncology. 2015;32(1):78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drezner N, Hardy KK, Wells E, et al. Treatment of pediatric cerebral radiation necrosis: a systematic review. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2016;130(1):141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Packer RJ, Zimmerman RA, Kaplan A, et al. Early cystic/necrotic changes after hyperfractionated radiation therapy in children with brain stem gliomas. Data from the Childrens Cancer Group. Cancer. 1993;71(8):2666–2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson MD Jr., Soni D, Baram TZ. Necrosis in pontine gliomas: radiation induced or natural history? Radiology. 1994;191(1):279–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexiou GA, Tsiouris S, Kyritsis AP, Voulgaris S, Argyropoulou MI, Fotopoulos AD. Glioma recurrence versus radiation necrosis: accuracy of current imaging modalities. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2009;95(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dequesada IM, Quisling RG, Yachnis A, Friedman WA. Can standard magnetic resonance imaging reliably distinguish recurrent tumor from radiation necrosis after radiosurgery for brain metastases? A radiographic-pathological study. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(5):898–903; discussion 904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li YQ, Ballinger JR, Nordal RA, Su ZF, Wong CS. Hypoxia in radiation-induced blood-spinal cord barrier breakdown. Cancer research. 2001;61(8):3348–3354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong CS, Van der Kogel AJ. Mechanisms of radiation injury to the central nervous system: implications for neuroprotection. Molecular interventions. 2004;4(5):273–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartholdi D, Rubin BP, Schwab ME. VEGF mRNA induction correlates with changes in the vascular architecture upon spinal cord damage in the rat. The European journal of neuroscience. 1997;9(12):2549–2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delishaj D, Ursino S, Pasqualetti F, et al. Bevacizumab for the Treatment of Radiation-Induced Cerebral Necrosis: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of clinical medicine research. 2017;9(4):273–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nordal RA, Nagy A, Pintilie M, Wong CS. Hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 target genes in central nervous system radiation injury: a role for vascular endothelial growth factor. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2004;10(10):3342–3353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lubelski D, Abdullah KG, Weil RJ, Marko NF. Bevacizumab for radiation necrosis following treatment of high grade glioma: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2013;115(3):317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torcuator R, Zuniga R, Mohan YS, et al. Initial experience with bevacizumab treatment for biopsy confirmed cerebral radiation necrosis. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2009;94(1):63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadraei NH, Dahiya S, Chao ST, et al. Treatment of cerebral radiation necrosis with bevacizumab: the Cleveland clinic experience. American journal of clinical oncology. 2015;38(3):304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levin VA, Bidaut L, Hou P, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of bevacizumab therapy for radiation necrosis of the central nervous system. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2011;79(5):1487–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu AK, Macy ME, Foreman NK. Bevacizumab as therapy for radiation necrosis in four children with pontine gliomas. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2009;75(4):1148–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster KA, Ares WJ, Pollack IF, Jakacki RI. Bevacizumab for symptomatic radiation-induced tumor enlargement in pediatric low grade gliomas. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2015;62(2):240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Billson AL, Walker DA. Assessment of health status in survivors of cancer. Archives of disease in childhood. 1994;70(3):200–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar AJ, Leeds NE, Fuller GN, et al. Malignant gliomas: MR imaging spectrum of radiation therapy- and chemotherapy-induced necrosis of the brain after treatment. Radiology. 2000;217(2):377–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mullins ME, Barest GD, Schaefer PW, Hochberg FH, Gonzalez RG, Lev MH. Radiation necrosis versus glioma recurrence: conventional MR imaging clues to diagnosis. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 2005;26(8):1967–1972. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.