Abstract

Growing concern about major threats, including climate change, environmental disasters, and other hazards, is matched with the increased interest and appeal of the concept of urban resilience. Much scholarly attention has focused on how to define urban resilience, in addition to raising questions about its applicability and usefulness. But those debates typically overlook questions of implementation. Implementation is important not only for how cities respond to threats but also because it can influence how urban resilience is perceived, discussed, and understood. The policy literature suggests that implementation is rarely straightforward and has ideological and normative perspectives embedded within it. Building on this literature, this paper argues that urban resilience implementation raises its own conceptual questions for both theory and practice. Further, implementing urban resilience entails its own unique challenges, such as extensive coordination, maintaining adaptability, divergent time horizons, and diverse outcomes. The paper also introduces the idea of resilience resistance as a new challenge for urban resilience. Resistance refers to the condition in which governance systems inherently develop barriers to change, flexibility, and adaptability through implementation. Several aspects of resistance are highlighted, including fatigue, complacency, and overconfidence. However, the implementation process can also have unintended positive effects on a city's capacity to prepare for and respond to shocks.

Keywords: Policy implementation, Resilient cities, Resistance, Urban resilience

Highlights

-

•

Debates about urban resilience may overlook the importance of policy implementation

-

•

How policies are implemented can influence discussions and understanding of the concept of urban resilience

-

•

Urban resilience implementation raises its own conceptual questions for theory and practice

-

•

Implementation can lead to resilience resistance, which reduces the capacity for cities to respond to shocks and stresses

1. Introduction

The concept of resilience has captured the popular imagination and is increasingly applied to cities and urban areas. Recent interest appears to coincide with growing attention and concern about threats like climate change, disease outbreaks, environmental disasters, terrorism, and other hazards (United Nations, 2015; World Bank, 2019). As climate change contributes to larger and longer lasting disasters, more frequent threat incidents, and more extreme weather-related events, the discussion and interest in urban resilience is expected to grow (for example, Jabareen, 2013; Vale, Shamsuddin, & Goh, 2014). Similarly, the recent spread of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 highlights the fragility of urban systems in the face of contagion and the need for better preparation and response. Further, global urbanization trends, in which an increasing proportion of the world's population resides in urban areas, puts more people at risk. The combination of threats and urbanization will draw heightened attention to how cities can become more resilient and what they are actually doing about it.

Much academic energy has focused on efforts to define the concept of resilience, criticism of the vagueness of the term, and questions about its applicability and usefulness, but often overlooks the key issue of implementation. Drawing upon various academic disciplines, it is possible to identify different definitions of resilience that can be applied to cities (Godschalk, 2003; Meerow, Newell, & Stults, 2016; Pickett, Cadenasso, & Grove, 2004; Vale, 2014). But some observers point out that the term resilience is at best imprecise and may simply be replacing other ambiguous and slippery terms like sustainability (Davoudi, 2012; Normandin, Therrien, Pelling, et al., 2019; Torabi, Dedekorkut-Howes, & Howes, 2018). Others ask whether the capacious and expansive nature of the concept makes it impractical for achieving any of the goals that might be associated with urban resilience (Beilin & Wilkinson, 2015). These debates have been useful in exploring the potential—and potential limitations—of the concept of urban resilience. Prior work has raised important questions about urban resilience for whom, what, when, where, and why (Carpenter, Walker, Anderies, & Abel, 2001; Friend & Moench, 2013; Meerow & Newell, 2019; Pendall, Foster, & Cowell, 2010; Vale, 2014). But discussion of these issues is incomplete without also addressing the issue of how, including how is urban resilience implemented and how is implementation understood.

Scholars have pointed out the need to develop better links between urban resilience theory and practice to help in closing the implementation gap (Coaffee et al., 2018; Coaffee & Clarke, 2015). As Therrien, Matyas, Usher, Jutras, and Beauregard-Guerin (2017) observe, “Despite the growing popularity of the term, there is an important gap between the discourse on urban resilience and the capacity to develop resilience in practice.” Despite questions about how to operationalize it, there is increased understanding and knowledge of how to apply the concept of resilience to cities and urban areas (Chandler & Coaffee, 2016). There is a proliferation of government and non-government publications that offer instructions and guides on how to build resilience (for example, Rockefeller Foundation, 2014; United Nations, 2015; World Bank, 2019). Prior studies have examined efforts to improve resilience but they tend to focus on a single city or place (for example, Chmutina, Lizarralde, Dainty, & Bosher, 2016; Spaans & Waterhout, 2017).

Past work and the gap between theory and practice raise the question: can urban resilience as applied ever live up to the concept? Discussions focused on the concept may be more appealing because they can sidestep and avoid the messy details and reality involved in applications to practice. But urban resilience, as it is conceived and debated, is intended to address real threats, real risks, and real vulnerabilities.

Implementation is an important issue not only for how cities respond to threats but also because it can influence our understanding of the concept of urban resilience. There is an extensive policy literature on implementation that indicates, like urban resilience, the idea is multidimensional and highly contested. Building on the policy literature, this paper argues that urban resilience implementation raises its own conceptual questions that must be grappled with and addressed. In addition, the implementation process creates challenges for practical efforts to enhance resilience in urban areas. These challenges include extensive coordination, maintaining adaptability, divergent time horizons, and diverse outcomes. The paper focuses on implementation barriers and introduces the idea of resilience resistance as a new challenge for urban resilience. Resistance refers to the condition in which governance systems inherently develop barriers to change, flexibility, and adaptability through implementation. There are three key aspects of resilience resistance: fatigue, complacency, and overconfidence. However, the implementation process can also have unplanned positive effects on a city's capacity to prepare for and respond to shocks. Scholars and practitioners must recognize and engage with both the challenges and implications of implementation for urban resilience. Ultimately, implementation hurdles, barriers, and realities may force a reexamination of how urban resilience is conceived, communicated, and practiced.

2. The resilience of resilience

Much scholarly attention has focused on the concept and definition of urban resilience. An early example of applying the idea of resilience to cities, indeed the term “resilient city,” arises from the study of how cities recover from disasters (Vale & Campanella, 2005). Different fields, including engineering, ecology, and psychology, have developed their own definitions and meanings of resilience, which can and have been applied to urban areas (Ahern, 2011; Godschalk, 2003; Meerow et al., 2016; Pickett et al., 2004; Pizzo, 2015; Vale, 2014). Drawing upon this work, there are at least three widely discussed notions of urban resilience. From an engineering perspective, urban resilience describes the capacity of a city to absorb change or stress and return to its previous state (Holling, 1973). From an ecological perspective, urban resilience refers to the capacity of a city to adjust to a shock or disaster without severe damage to existing structures and relationships (Holling, 1996; Pickett, McGrath, Cadenasso, & Felson, 2014). From a socioecological or evolutionary perspective, urban resilience describes the capacity of a city to adapt or transform in response to a change or shock (Davoudi, 2012; Folke et al., 2010; Wilkinson, 2012). In recent years, scholarly explorations of the connections between resilience and cities have grown as demonstrated by a large expansion in the number of published papers using terms like urban resilience, city resilience, resilient city, or resilient cities (Meerow & Newell, 2019; Pu & Qiu, 2016).

The increased popularity of the term urban resilience has been accompanied by more critical observations about how the term is used and what it means. Many scholars have noted problems including the difficulty in formulating a consistent, useful definition, that is, a definition that is not so broad that it essentially can include anything and everything. (Beilin & Wilkinson, 2015; Vale, 2014). Others have noted the lack of precision and clarity in how the term is defined and used (Normandin et al., 2019). Resilience may be simply replacing sustainability as another term with widespread appeal despite (or perhaps because of) a lack of clarity (Davoudi, 2012).

However, the multiple meanings of urban resilience may be an asset. The openness of the term to interpretation means it can be used as a metaphor to garner support and encourage political movement (Béné, Newsham, Davies, Ulrichs, & Godfrey-Wood, 2014; Carpenter et al., 2001; Pain & Levine, 2012). Similarly, a flexible understanding of resilience can make it easier to accommodate different opinions, perspectives, priorities, or groups. Resilience is a “highly complex, malleable and dynamic political construct … due to its vagueness, resilience now plays a role of a term that facilitates communication across various disciplines and it often creates a perception of a shared vocabulary” (Chmutina et al., 2016). The fact that different people, groups, communities, and fields can impart and find their own meaning in resilience may help explain the term's persistent use and appeal. Indeed, the malleability of the term “resilience” contributes to its own resilience.

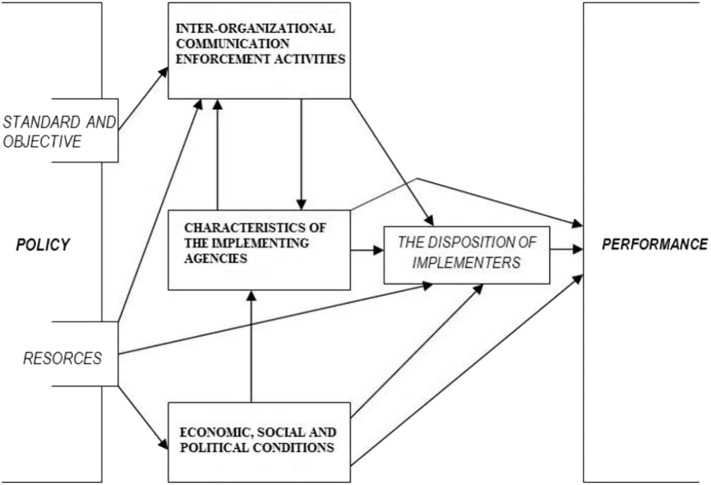

The concept of urban resilience may be traveling along the path of a life cycle that is commonly used to describe emerging technologies. The Hype Cycle shows how a technology moves from conception to maturity to widespread adoption. See Fig. 1 . In the initial phase when technology is first introduced, there is great optimism and excitement about its potential. In a short period of time, the technology reaches the “Peak of Inflated Expectations” as much of the optimism is overblown. This stage is quickly followed by a “Trough of Disillusionment” during which criticism and skepticism outweigh interest as experiments with the technology fail to meet expectations. Over a longer period of time, the technology may enter the “Slope of Enlightenment” as expectations more slowly rise in pace with examples of how the technology may benefit users. In the final phase, the technology enters the “Plateau of Productivity” as mainstream adoption of the technology finally begins. In its initial phase, the concept of urban resilience was met with seemingly unbounded—and unrealistic—optimism about its potential to “save” cities from disasters. This was quickly followed and tempered by criticism about the fuzziness of the concept and questions about its applicability to social systems. Supporters and detractors of the concept of urban resilience will likely disagree about the term's current position along the cycle and the speed with which it will move. But it is clear that as cities move forward with developing resilience policies, implementation will influence how the concept is perceived, used, and advanced.

Fig. 1.

The hype cycle for emerging technologies (Gartner, n.d.)

Although the attention to definitions is both necessary and useful for theory and scholarship, from the perspective of policy implementation it may be incomplete, or at least premature. From a scholarly point of view, one reason is that the experience of implementing urban resilience policies and programs may shape and influence our understanding of how the term urban resilience can and should be conceived. Implementation provides an opportunity to study how different sets of actors understand and make sense of the term resilience. Measured outcomes—or lack thereof—will influence how resilience as a term is understood. Consequently, application and implementation will help (re)shape the definition of urban resilience. From a practitioner's point of view, cities will adopt and adapt approaches to urban resilience that fit their individual and local needs, capacity, and historical experience. A single definition, no matter the level of agreement and precision, may not fully capture a specific city's circumstances or be essential to its pursuit of increasing its capacity to withstand and respond to shocks. As urban resilience is put into practice, the precise definition of the term—and its applicability to different contexts—may recede in importance. Finally, despite concerns about imprecision, the ambiguity of the concept may be beneficial from a preparedness standpoint. Multiple interpretations of resilience may encourage multiple strategies to address multiple threats, which may prove more effective than a single approach. Of course, an overly imprecise understanding could be detrimental if it leads to confusion and conflict during implementation.

At a fundamental level, how resilience is defined shapes the measures, boundaries, and expectations for implementation. But there is a feedback loop. Implementation will inform how resilience is described, communicated, understood, redefined, and eventually practiced.

3. Policy implementation frameworks

Scholars have offered numerous ways of defining and describing what implementation is. A basic and central component of implementation is “to establish a link that allows the goals of public polices to be realized as outcomes of governmental activity” (Grindle, 2017: 6). In other words, implementation entails a “policy delivery system” that designs specific means for translating policy goals into specific outcomes (Van Meter & Van Horn, 1975). Implementation can also be thought of as a process. It is “the carrying out of a basic policy decision … that identifies the problem(s) to be addressed, stipulates the objective(s) to be pursued, and in a variety of ways, ‘structures’ the implementation process” (Mazmanian & Sabatier, 1983: 20). Implementation also can be understood as part of a policy-action relationship, “a process of interaction and negotiation, taking place over time, between those seeking to put policy into effect and those upon whom action depends” (Barrett & Fudge, 1981: 4). The multiple descriptions point toward debate and disagreement about where policymaking stops and implementation begins.

These descriptions also imply different sets of relationships and levels for understanding policy implementation. Early work suggested there are two levels of policy implementation: principal policymakers create a government program at the macro-implementation level, while local organizations develop their own programs and implement them at the micro-implementation level (Berman, 1978).

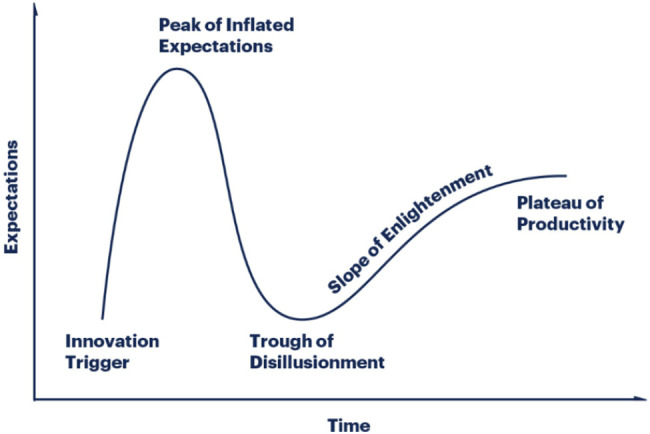

Much additional scholarship can be organized around three perspectives for studying implementation: top-down, bottom-up, and mixed approaches. In the top-down perspective, implementation is understood in relation to policy that is given in official documents (Hill & Hupe, 2002). The action of implementing the policy will depend on the difficulty of the problem the policy is intended to address and the types of structures and resources put in place by the policy statement (Mazmanian & Sabatier, 1983). The basic model proceeds from policy statements to organizational characteristics and macro conditions to the nature of the “implementers,” and then finally performance (Van Meter & Van Horn, 1975). See Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Policy implementation process model (Van Meter & Van Horn, 1975).

In the top-down model, there are several factors that can affect the likelihood of favorable implementation outcomes. Successful implementation can depend on the number of and degree of cooperation between agencies and organizations involved (Pressman & Wildavsky, 1984). It can be affected by the amount of change necessary and the level of agreement or consensus that exists (Van Meter & Van Horn, 1975). The success of implementation can also be influenced by how policy scenarios are structured in order to lead to—or even pre-determine—sought after outcomes (Bardach, 1977).

The bottom-up approach challenges some of the hierarchical views about how organizations work that are assumed in top-down models (Hill & Hupe, 2002). From the bottom-up perspective, implementation crucially depends on communication and compromise between people working in policy-related organizations; they interpret and modify policy through their actions (Barrett & Fudge, 1981). The front-line staff in policy delivery agencies can have an outsized influence on implementation through their day-to-day discretionary actions and decisions—indeed, these activities in many ways become the policy (Lipsky, 1980). Further, street level bureaucrats deal with the pressures of constant need but inadequate time and resources by developing routines that determine how policy implementation takes place (Lipsky, 1980).

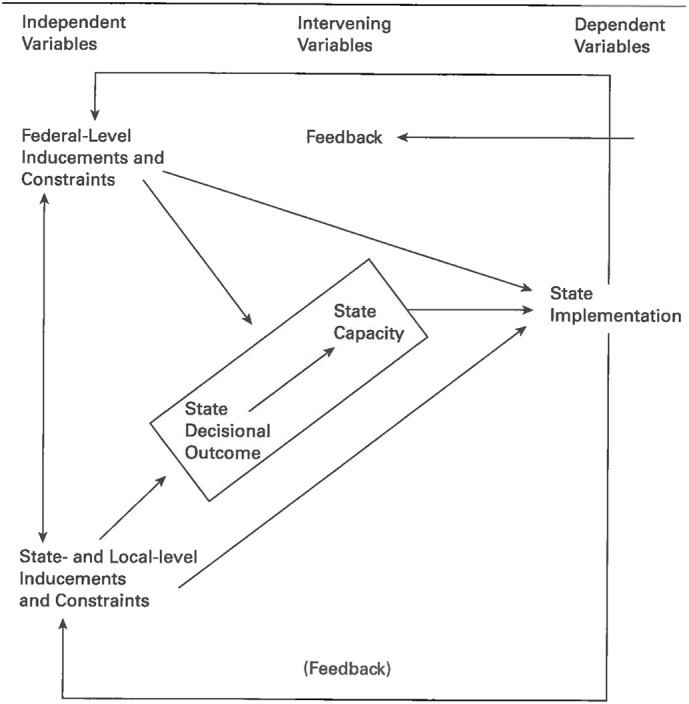

In response to the top-down and bottom-up perspectives, some scholars have put forward alternative perspectives on implementation that mix different approaches. An advocacy coalition framework may help synthesize the top-down and bottom-up approaches by capturing the various public and private actors at all levels who participate in implementation, along with the social and economic conditions in which they operate (Sabatier, 1986). The communications model accounts for the factors, including federal, state, and local inducements and constraints, organizational and ecological capacity, and feedback, that affect how intergovernmental messages are accepted or rejected (Goggin, Bowman, Lester, & O'Toole Jr, 1990). See Fig. 3 . The concept of policy networks may be appropriate for understanding the interactions, including coordination and collaboration, between multiple actors (Scharpf, 1978). Further, collaborative networks may be a key component of successful implementation.

Fig. 3.

Communications model of implementation (Goggin et al., 1990).

Complicated events like policy implementation may call for multiple organizational models to study them, including implementation as systems management, implementation as bureaucratic process, implementation as organization development, and implementation as conflict and bargaining (Elmore, 1978). Policies and programs rarely operate in isolation so these models may help in understanding how implementers make choices between programs that interact or even conflict. Instead of treating all policies the same, it might be useful to consider how implementation differs across various policy types, such as distributive, regulatory (competitive and protective), and redistributive policies (Ripley & Franklin, 1982). An alternative approach uses four policy implementation paradigms to understand policies as having different levels of ambiguity and conflict: 1) administrative implementation, which involves low conflict and low ambiguity, 2) political implementation, which involves high conflict and low ambiguity, 3) symbolic implementation, which involves high conflict and high ambiguity, and 4) experimental implementation, which involves low conflict and high ambiguity (Matland, 1995).

An extensive literature shows that implementation is rarely straightforward (Grindle, 2017; Mazmanian & Sabatier, 1983; Pressman & Wildavsky, 1984; Van Meter & Van Horn, 1975). It can be a complex activity with multiple dimensions. Many factors can influence implementation, including the availability of resources, the relationships between (and within) government agencies, the commitment of officials, reporting procedures and mechanisms, timing, and luck (Grindle, 2017). In addition, policy implementation substantially depends on individuals and how they interpret messages. As Majone and Wildavsky (1978) observe, “Policy ideas in the abstract … are subject to an infinite variety of contingencies, and they contain worlds of possible practical applications. What is in them depends on what is in us, and vice-versa” (113). Further, an important aspect of implementation is how those tasked with implementation perceive and make sense of policies, and how much agents alter their beliefs and attitudes through the implementation process (Spillane, Reiser, & Reimer, 2002).

4. Urban resilience implementation challenges

The policy implementation literature raises many questions for urban resilience implementation, including the fundamental issue of what is meant by implementation. Any discussion of urban resilience implementation must establish where implementation begins and ends, in addition to what is included and excluded. The distinction between implementation and policymaking may be even less clear in the case of urban resilience because of the fuzziness of the concept and the multiplicity of issues involved. The policy frameworks described above suggest the crucial need for discussions of urban resilience implementation to consider how implementation is conceived. Is urban resilience implementation understood from a top-down approach, a bottom-up approach, or some combination? In addition, consideration must be given to how urban resilience policies are categorized and how different types of urban resilience policies are treated.

The implementation literature and policy frameworks bring to the forefront that discussions and study of urban resilience implementation are not neutral; the study of how urban resilience—or any other policy or program—is implemented has ideological or normative perspectives embedded within it (Hill & Hupe, 2002). The models also help remind us that implementation of urban resilience is not solely about results. Implementation is a complex process involving multiple levels, scales, and actors. These dimensions must be acknowledged and carefully considered, in addition to the standard questions about outcomes, outputs, and operationalization.

Urban resilience implementation involves cooperation and collaboration between government agencies, non-governmental organizations, private businesses, and the public. Attempts to pursue urban resilience often lead to trade-offs where improved resilience for some systems, scales, and time periods may result in decreased resilience for others (Chelleri, Waters, Olazabal, & Minucci, 2015). This raises important questions of whether this is a zero-sum game or whether there are ways to make Pareto improvements to resilience for multiple systems, scales, and time periods.

Urban resilience implementation creates a set of special challenges: extensive coordination between government and non-governmental organizations; maintaining adaptability to changing social, political, economic, and environmental conditions, divergent time horizons between the period of implementation and the anticipated threat, and diverse outcome to be measured and evaluated. These are in addition to the traditional challenges of resources, political will, and adoption.

4.1. Resilience resistance

Urban resilience also faces an important and previously unacknowledged challenge: resistance. The existing urban resilience literature typically treats resistance as either a conceptual alternative to resilience or as an important component of resilience. As an alternative to resilience, resistance suggests social structures persist in the face of disasters or other threats (Chelleri, 2012). As a component of resilience, resistance is one quality among many, including coping capacity, recovery, and adaptive capacity (Johnson & Blackburn, 2014). However, resistance can be conceived of and applied to urban resilience in a different manner that implicates implementation.

This alternative notion of resistance is based on the medical and public health literatures on infection treatment and response. It draws upon the biological phenomenon of antibiotic resistance, in which antibiotic medications are used to prevent or treat infections. Bacteria may change in response to the use of medicine. The bacteria may even stop responding to the medicine, making infection more difficult to treat. The application of the treatment eventually makes matters worse.

In the urban context, resilience resistance refers to the process in which governance systems—through normal, everyday operations—develop barriers or hurdles to achieving urban resilience.1 The barriers can take many forms, including organizational and psychological. These barriers make it more difficult to achieve resilience oriented goals. The barriers can erode the commitment of policymakers and leaders; lower the motivation of personnel charged with implementing policies; reduce the capacity of government agencies and non-governmental organizations to respond to needs; slow or impede progress toward policy goals; and ultimately reduce the capacity of cities to improve urban resilience. The process of developing and building resistance is completely natural and might be inherent in many forms of governance. The obstacles emerge from the standard functions of both government agencies and non-government organizations. Paradoxically, these barriers to resilience directly arise from efforts to increase or improve resilience.

An important aspect of resilience resistance is the accumulation of entrenched bureaucratic structures that weigh down governance, slow operations, and decrease flexibility. These structures can include administrative procedures, management hierarchies, multiple levels of decision making and approval, and regulatory oversight.2 It is important to note that, for example, the administrative procedures need not be onerous or the management hierarchies rigid for these structures to have an effect. The sheer number, size, and accumulation of these structures make it harder to be nimble and adapt. Once the procedures, hierarchies, decision making chains, and oversight are established, they can be extremely difficult to change. Sometimes, even efforts to streamline or ‘cut red tape’ can backfire and lead to reduced efficiency. The accumulated mass of bureaucratic structures can stifle urban resilience implementation by government agencies and non-governmental organizations.

The implementation process naturally creates impediments to efficient and effective means of achieving urban resilience goals. It does not require “bad actors,” subversion, sabotage, or even incompetence. Indeed, resistance can occur even if implementation is faithfully pursued. The problems of resistance can arise even if we ignore the traditional challenges of adequate financial resources, capable personnel, sufficient time, and political will. Although the hurdles frequently arise during policy implementation, they may occur in other parts of the policy process as well.

Resilience resistance differs from antibiotic resistance in an important respect. In urban resilience, there are natural threats but they do not evolve like microbes in direct response to interventions. In other words, storms, floods, and earthquakes do not change because of resilience efforts. (However, there is a concern that climate change will worsen these threats by increasing their frequency, duration, and force. To the extent that human actions make the problem worse, interventions could influence and exacerbate threats.) Resistance to urban resilience is similar to antibiotic resistance in that both can lead to higher government expenses, longer response and recovery times, and increased risk of harm or damage.

One reason resilience resistance is a concern is that, like antibiotic resistance, it can lead to system wide problems. Resilience resistance has the potential to affect the entire operations of an organization, including agenda setting, initiation, information gathering, decision making, and implementation. Further, no government agency, for example environment, emergency management, energy, or housing, is immune. Consequently, resistance can potentially reduce resilience to all types of threats, scales, or timeframes. The widespread impact reaches farther than the tradeoff of increasing resilience to one threat at the expense of another (Chelleri et al., 2015).

Based on the challenges and pitfalls to policy implementation noted in the literature (e.g. Pressman & Wildavsky, 1984) there are three psychological aspects of resistance that are particularly relevant to urban resilience efforts. The aspects are: 1) fatigue, 2) complacency, and 3) overconfidence. Brief descriptions follow below. Although there are other forms resistance can take, including apathy, obstruction, and despondency,3 these forms of resistance are highlighted because they occur even with broad agreement or adoption of policy needs and goals, and because of the potentially outsized effects on both theory and practice. It is important to note that these forms of resistance can occur if implementation is judged to be successful or unsuccessful.

4.1.1. Fatigue

Fatigue refers to how government personnel, partner organization staff, and segments of the public may grow tired of urban resilience policy discussions. These groups may become weary of resilience policy announcements and policy directives. The repeated communication and messaging around urban resilience may have a desensitizing effect on various target audiences. Similarly, groups may become desensitized to constant discussion of threats and risks. Excess messaging about implementation can lead to oversaturation and reduced ability to inspire or catalyze change around urban resilience. The consistent effort or constant vigilance required in the face of such large challenges like urban resilience can be physically and mentally exhausting. As a result, those groups charged with the tasks of leading, coordinating, and collaborating to implement urban resilience policies may become slow to react or less responsive to the latest initiatives or directives. The decreased responsiveness can make it difficult to achieve desired urban resilience outcomes both in the present and in the future. Fatigue is more likely if urban resilience policy takes on multiple iterations, especially if those iterations involve real or perceived errors, retractions, corrections, and changes. Over time, urban resilience policies may be viewed by target audiences as just another policy pronouncement among many. Key actors may still engage in performing tasks necessary for policy implementation but their efficiency will be compromised. For example, repeated policy directives on earthquake preparedness may lead government agencies and local organizations coordinating on earthquake response to be slow to set up meetings, provide updates on progress, or seek public feedback.

4.1.2. Complacency

Complacency can occur as a result of the implementation process, especially if implementation is considered successful. Complacency can involve a reduced sense of concern or attentiveness to the problems that urban resilience policies are intended to address. By implementing an urban resilience policy or program, policy leaders, ground-level staff, and the public may develop a false sense of security and be lulled into the belief that the threat is no longer a concern. Further, the scale or magnitude of the threat may be perceived as smaller or more manageable because policies have been put in place. Complacency can arise, for example, with the creation, organization, and staffing of a flood control office. Officials and the public may feel a city is prepared for a flood simply by establishing the office, so flooding is no longer perceived as a serious threat. By virtue of putting a policy in place and feeling satisfied with the results, involved groups may become untroubled by potential risks and vulnerabilities. As urban resilience implementation becomes more familiar, it may also become mainstream in the sense of no longer being viewed as novel, different, or worthy of the same kind of attention it initially had drawn. At one level, officials may desire adoption of urban resilience as normal practice. At another level, normalization may decrease sense of urgency and attentiveness to the problem. Eventually, urban resilience may slowly lose its priority status. It may no longer stand out or be on the forefront of people's minds.

4.1.3. Overconfidence

Overconfidence involves excessive, unsubstantiated faith in the ability of urban resilience policies to be effective against potential threats. Although the focus here is on implementation, overconfidence can emerge and affect all stages of the policy process. If optimism about current and future policy outcomes goes too far, government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and the public may believe they are fully prepared and completely ready for a threat. Further, overconfidence may lead actors to feel additional work and preparation are not necessary. For example, enacting and enforcing strict building codes after a hurricane caused damage to property may prompt leaders to believe that the next hurricane will result in less damage and more houses and people will be saved. Further, there may be a feeling that too much work, that is urban resilience preparation, was done. This can lead to scaling back of operations and resources, which ultimately makes a city underprepared for a threat. Overconfidence can also lead to sloppiness and careless mistakes, as oversight is considered unnecessary and a waste of resources.

4.2. Potential positive effects

Despite the challenges of fatigue, complacency, and overconfidence, implementation can also have positive effects on urban resilience. The implementation process itself can be viewed as a form of urban resilience. Through implementation, government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and other actors interact and develop capacity. Ideally, they develop and establish lines of communication. They may: i) become more aware and knowledgeable about related and overlapping activities; ii) discover and encounter barriers to implementation; and iii) engage in problem-solving to address and overcome these barriers. Similarly, implementation can be understood as a process or system of exploration, learning, and adaptation (Majone & Wildavsky, 1978). Through implementation, city programs adapt to local circumstances, which may contribute to increased resilience.

Some urban resilience policies ultimately may not be effective, in the sense of improving a city's capacity to withstand a weather-related disaster or other unexpected shock, no matter how well-intentioned they are. But the practice of putting those policies in place can nonetheless affect urban resilience in the short- and long-term. Working with stakeholders to develop accountability mechanisms and procedures may help with future urban resilience policies and activities. Further, there is the potential that implementation processes may improve urban resilience in ways beyond the intended outcome. For example, the creation of a community forum to discuss environmental disaster preparedness might improve community relations in ways that increase resilience to other concerns like terrorism or crime.

5. Implementation for practice and theory

Implementation links theory to practice but it also links practice to theory. The process of implementation can inform the concept of urban resilience through a feedback loop. In other words, the manifestation of urban resilience implementation may shift understanding of resilience. For example, the installation of storm surge barriers can reframe thinking about resilience in terms of physical threats and responses. This is especially the case because of the difficulty in drawing a clear line where policymaking ends and implementation begins. Indeed, how urban resilience policy is implemented will influence what urban resilience means. In this way, implementation offers a testing ground for proof of the concept of urban resilience. Implementation can reveal the value of a definition of resilience and where it falls short, which may lead to subsequent reformulations.

There is a natural human tendency to focus on threats that are known. After all, these are the threats of which we are aware and, presumably, to which we can better respond. Threats that are identified and measurable are to some extent more manageable than unforeseen or unexpected ones. It is also far easier to evaluate and assess progress based on past experience with threat. But the process of responding to a threat or preparing for a future instance of that threat can take a life of its own as systems are put in place. Over time, these systems become increasingly oriented toward past examples of the threat. For example, prior to the September 11th terrorist attacks in the U.S. there was little attention to the potential use of commercial airplanes as weapons to conduct terrorism through hijackers taking control of the cockpit. Since that time, there are many safeguards in place for that specific threat, such as reinforced cockpit doors and rules against congregating in the front of the plane. But these actions are backward looking; they do little to acknowledge the changing nature of a threat. Another potential negative consequence of this focus is that unobserved threats may grow in force. It may also make it harder for cities to respond to future unobserved threats because their attention, resources, and focus is elsewhere, that is, on the known threats. In these ways, the process of implementation redefines the threat and thereby affects the conception of resilience.

For urban resilience, the issue is not how well does implementation and practice match up to the ideal offered by the concept. Instead, the issues are how useful is the concept for guiding implementation and how does the implementation process affect the concept.

Finally, the potential for social justice in urban resilience lies in implementation. Prior work highlights the importance of considering urban resilience in terms of who, what, when, where, and why (Carpenter et al., 2001; Friend & Moench, 2013; Meerow & Newell, 2019; Pendall et al., 2010; Vale, 2014). Implementation reveals the need to also consider how. It is not just about for whom urban resilience is pursued but also how they are involved, considered, and treated. For example, flood risk resilience may target historically marginalized or disadvantaged groups but their voices and concerns could be minimized, dismissed, or even ignored. It is not just about where urban resilience is sought but also how the process takes place. Low-income neighborhoods may be targeted for hurricane resilience programs but the programs could result in displacement or removal of long-term residents. It is not just about resilience of what to what but also how that resilience is introduced and established. Programs to improve the resilience of residential buildings to earthquakes may result in such high housing costs that few households can benefit. Examples from around the world suggest that uncritical efforts to expand resilience may ignore social justice and may harm disadvantaged groups (Anguelovski et al., 2016; Shamsuddin & Srinivasan, 2020; Vale, Shamsuddin, Gray, & Bertumen, 2014; Ziervogel et al., 2017). Further, it is important to acknowledge the potential and power of other kinds of threats that are not traditionally discussed in the urban resilience literature. A key question for cities in the U.S. and around the world is how can they be resilient to political threats? This can include national or federal leadership that is antagonistic and hostile to large segments of urban populations, and by extension, the cities that house them.

6. Conclusion

Substantial academic effort has been devoted to unpacking the multiple disciplinary meanings of the concept of urban resilience, criticizing the lack of clarity of the term, and debating its usefulness. Despite the stated importance of enhancing the capacity of cities to be resilient, much work has focused on defining the concept of urban resilience instead of determining how to implement policies that would promote urban resilience. Indeed, the focus on defining the term and the attendant critiques risk overlooking the challenges and implications of urban resilience implementation. As cities move to develop and enact policies to increase their capacity to respond to threats, this raises important questions about how implementation affects urban resilience. As Pressman and Wildavsky (1984) noted in their in depth analysis, “the attempt to study implementation raises the most basic question about the relation between thought and action: How can ideas manifest themselves in a world of behavior?” (163).

The policy literature provides useful analytical frameworks for studying different dimensions of implementation, including pathways, mechanisms, key actors, and stakeholders. Adapting these models to the practice of urban resilience requires acknowledging some special characteristics of resilience planning and operations. These characteristics include: extensive coordination, maintaining adaptability, divergent time horizons, and diverse outcomes. These characteristics also create a new challenge: resilience resistance. Resistance refers to the condition in which governance systems inherently develop barriers to change, flexibility, and adaptability through implementation. Important aspects of resistance include fatigue, complacency, and overconfidence.

Threats, policy development, and implementation are an iterative process. As cities seek to implement policies to improve their urban resilience, there is a need to develop better links between theory and practice. Instead of avoiding consideration of or even reference to implementation in discussions about the definition of urban resilience, scholars and practitioners should engage and embrace it. Careful attention and understanding of implementation and implementation barriers can provide valuable feedback, improve concepts of resilience, and make urban resilience more useful and effective.

Credit authorship contribution statement

Shomon Shamsuddin: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Footnotes

Resilience resistance can also be used to describe resistance to adoption and implementation of policies that promote urban resilience. This can take the form of active resistance, for example because of ideological differences, or passive resistance, for example because of unappealing aspects of change.

Resilience resistance can also emerge from mission creep, additional responsibilities, and expanded operations.

For example, government workers, partner organization personnel, and the public may become despondent in response to policy implementation around urban resilience. The unattainability of the ideal may sap motivation. The goals articulated or tasks assigned may appear to be impossible to achieve. Consequently, these key actors may feel the cause of urban resilience is hopeless. Despair may lead to failure to initiate or complete important tasks related to urban resilience policy implementation.

References

- Ahern J. From fail-safe to safe-to-fail: Sustainability and resilience in the new urban world. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2011;100(4):341–343. [Google Scholar]

- Anguelovski I., Shi L., Chu E., Gallagher D., Goh K., Lamb Z., Teicher H. Equity impacts of urban land use planning for climate adaptation: Critical perspectives from the global north and south. Journal of Planning Education and Research. 2016;36(3):333–348. [Google Scholar]

- Bardach E. M.I.T. Press; Cambridge, MA: 1977. The implementation game. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett S., Fudge C. Policy and action: Essays on the implementation of public policy. 1981. Examining the policy-action relationship; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Beilin R., Wilkinson C. Introduction: Governing for urban resilience. Urban Studies. 2015;52(7):1205–1217. [Google Scholar]

- Béné C., Newsham A., Davies M., Ulrichs M., Godfrey-Wood R. Resilience, poverty and development. Journal of International Development. 2014;26(5):598–623. [Google Scholar]

- Berman P. Rand Corporation; Santa Monica, CA: 1978. The study of macro and micro implementation of social policy. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter S., Walker B., Anderies J.M., Abel N. From metaphor to measurement: Resilience of what to what? Ecosystems. 2001;4(8):765–781. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler D., Coaffee J. Routledge; New York: 2016. The Routledge handbook of international resilience. [Google Scholar]

- Chelleri L. From the resilient city to urban resilience. a review essay on understanding and integrating the resilience perspective for urban systems. Documents d’anàlisi Geogràfica. 2012;58(2):287–306. [Google Scholar]

- Chelleri L., Waters J.J., Olazabal M., Minucci G. Resilience trade-offs: Addressing multiple scales and temporal aspects of urban resilience. Environment and Urbanization. 2015;27(1):181–198. [Google Scholar]

- Chmutina K., Lizarralde G., Dainty A., Bosher L. Unpacking resilience policy discourse. Cities. 2016;58:70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Coaffee J., Clarke J. On securing the generational challenge of urban resilience. Town Planning Review. 2015;86(3):249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Coaffee J., Therrien M.-C., Chelleri L., Henstra D., Aldrich D.P., Mitchell C.L.…Rigaud E. Urban resilience implementation: A policy challenge and research agenda for the 21st century. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 2018;26(3):403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Davoudi S. Resilience: A bridging concept or a dead end? Planning Theory & Practice. 2012;13(2):299–333. [Google Scholar]

- Elmore R.F. Organizational models of social program implementation. Public Policy. 1978;26(2):185–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folke C., Carpenter S., Walker B., Scheffer M., Chapin T., Rockstrom J. Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecology and Society. 2010;15(4):20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Friend R., Moench M. What is the purpose of urban climate resilience? Implications for addressing poverty and vulnerability. Urban Climate. 2013;6:98–113. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner. (undated). Gartner hype cycle. Stamford, CT: Gartner, Inc.

- Godschalk D.R. Urban hazard mitigation: Creating resilient cities. Natural Hazards Review. 2003;4(3):136–143. [Google Scholar]

- Goggin M.L., Bowman A.O.M., Lester J.P., O’Toole L.J., Jr. Scott, Foresman; Glenview, IL: 1990. Implementation theory and practice: Toward a third generation. [Google Scholar]

- Grindle M.S. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 2017. Politics and policy implementation in the third world. [Google Scholar]

- Hill M., Hupe P. Sage Publications; London: 2002. Implementing public policy: Governance in theory and in practice. [Google Scholar]

- Holling C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1973;4(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Holling C.S. Engineering resilience versus ecological resilience. Engineering within Ecological Constraints. 1996;31(1996):32. [Google Scholar]

- Jabareen Y. Planning the resilient city: Concepts and strategies for coping with climate change and environmental risk. Cities. 2013;31:220–229. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C., Blackburn S. Advocacy for urban resilience: UNISDR’s making cities resilient campaign. Environment and Urbanization. 2014;26(1):29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky M. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1980. Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public service. [Google Scholar]

- Majone G., Wildavsky A. Implementation as evolution. In: Freeman H., editor. Policy studies annual review. Vol. 2. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Matland R.E. Synthesizing the implementation literature: The ambiguity-conflict model of policy implementation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 1995;5(2):145–174. [Google Scholar]

- Mazmanian D.A., Sabatier P.A. Scott Foresman; Glenview, IL: 1983. Implementation and public policy. [Google Scholar]

- Meerow S., Newell J.P. Urban resilience for whom, what, when, where, and why? Urban Geography. 2019;40(3):309–329. [Google Scholar]

- Meerow S., Newell J.P., Stults M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2016;147:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Normandin J.-M., Therrien M.-C., Pelling M. Urban resilience for risk and adaptation governance. Springer; 2019. The definition of urban resilience: A transformation path towards collaborative urban risk governance; pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Pain A., Levine S. Overseas Development Institute, Humanitarian Policy Group; London: 2012. A conceptual analysis of livelihoods and resilience: Addressing the insecurity of agency. HPG Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Pendall R., Foster K.A., Cowell M. Resilience and regions: Building understanding of the metaphor. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society. 2010;3(1):71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett S.T., Cadenasso M.L., Grove J.M. Resilient cities: Meaning, models, and metaphor for integrating the ecological, socio-economic, and planning realms. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2004;69(4):369–384. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett S.T., McGrath B., Cadenasso M.L., Felson A.J. Ecological resilience and resilient cities. Building Research & Information. 2014;42(2):143–157. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzo B. Problematizing resilience: Implications for planning theory and practice. Cities. 2015;43:133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Pressman J.L., Wildavsky A. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 1984. Implementation: How great expectations in Washington are dashed in Oakland; or, why it’s amazing that federal programs work at all, this being a saga of the economic development administration as told by two sympathetic observers who seek to build morals on a foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Pu B., Qiu Y. Emerging trends and new developments on urban resilience: A bibliometric perspective. Current Urban Studies. 2016;4(01):36–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ripley R.B., Franklin G.A. Dorsey Press; Homewood, IL: 1982. Bureaucracy and policy implementation. [Google Scholar]

- Rockefeller Foundation . Rockefeller Foundation; New York: 2014. City resilience framework – 100 resilient cities. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier P.A. Top-down and bottom-up approaches to implementation research: A critical analysis and suggested synthesis. Journal of Public Policy. 1986;6(1):21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Scharpf F.W. Interorganizational policy studies: Issues, concepts and perspective. In: Hanf K., Scharpf F.W., editors. Interorganizational policy making: Limits to coordination and central control. Sage Publications; London: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsuddin S., Srinivasan S. Just Smart or Just and Smart Cities? Assessing the Literature on Housing and Information and Communication Technology. Housing Policy Debate. 2020 doi: 10.1080/10511482.2020.1719181. In press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spaans M., Waterhout B. Building up resilience in cities worldwide–Rotterdam as participant in the 100 resilient cities programme. Cities. 2017;61:109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Spillane J.P., Reiser B.J., Reimer T. Policy implementation and cognition: Reframing and refocusing implementation research. Review of Educational Research. 2002;72(3):387–431. [Google Scholar]

- Therrien M.-C., Matyas D., Usher S., Jutras M., Beauregard-Guerin I. 2017. Implementing urban resilience: Enablers, impediments and trade-offs. [Google Scholar]

- Torabi E., Dedekorkut-Howes A., Howes M. Adapting or maladapting: Building resilience to climate-related disasters in coastal cities. Cities. 2018;72:295–309. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . United Nations; New York: 2015. Sendai framework on disaster risk reduction 2015–2030. UN Office for disaster risk reduction. [Google Scholar]

- Vale L.J. The politics of resilient cities: Whose resilience and whose city? Building Research & Information. 2014;42(2):191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Vale L.J., Campanella T.J. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. The resilient city: How modern cities recover from disaster. [Google Scholar]

- Vale L.J., Shamsuddin S., Goh K. Tsunami + 10: Housing Banda Aceh After Disaster. Places. 2014;December 2014 doi: 10.22269/141215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vale L.J., Shamsuddin S., Gray A., Bertumen K. What affordable housing should afford: Housing for resilient cities. Cityscape. 2014;16(2):21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Van Meter D.S., Van Horn C.E. The policy implementation process: A conceptual framework. Administration & Society. 1975;6(4):445–488. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson C. Social-ecological resilience: Insights and issues for planning theory. Planning Theory. 2012;11(2):148–169. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . World Bank; Washington, DC: 2019. Action plan on climate change adaptation and resilience: Managing risks for a more resilient future. [Google Scholar]

- Ziervogel G., Pelling M., Cartwright A., Chu E., Deshpande T., Harris, Pasquini L. Inserting rights and justice into urban resilience: A focus on everyday risk. Environment and Urbanization. 2017;29(1):123–138. [Google Scholar]