Editor—We report a cardiac arrest in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) after receiving succinylcholine for reintubation. It is well recognised that the neuromuscular blocking agent succinylcholine can lead to a life-threatening hyperkalaemia in critically ill patients. Succinylcholine causes depolarisation of the postsynaptic neuromuscular junction, resulting in efflux of intracellular potassium and a sudden increase in plasma potassium.1 Succinylcholine sensitivity can be increased in certain conditions as a result of up-regulation of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Predisposing conditions include neuromuscular wasting disorders, severe burn injury, spinal cord trauma, and ICU immobilisation. Although succinylcholine is commonly used, there are surprisingly few studies and well documented case reports published on this subject.2

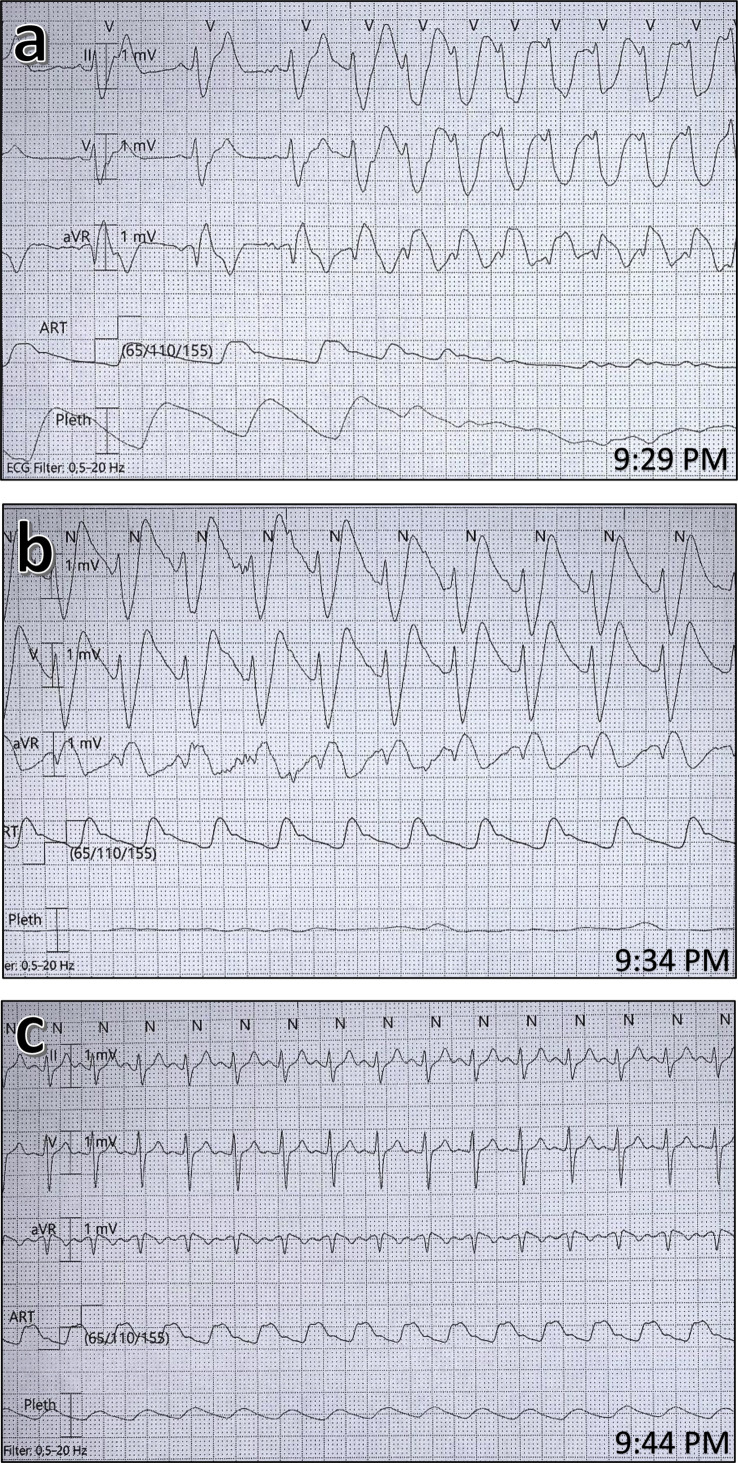

A 66-year-old woman was hospitalised in our ICU for 17 days on a mechanical ventilator with serious acute respiratory distress syndrome as a result of a COVID-19 infection. She had been weaned off the ventilator in gradual stages as her clinical situation improved, but 1 day after extubation, she had sudden respiratory deterioration with severe haemoglobin oxygen desaturation as a result of bronchial secretions, and became unresponsive but was still breathing. Despite receiving oxygen 100% via a facemask, oxygen saturation only reached 80%–85%. As hypoxaemic cardiac arrest was imminent, the decision was made to reintubate the patient using rapid sequence induction (RSI). A blood gas sample obtained moments before intubation revealed hypoxaemia and respiratory acidosis (pH 7.28, P o 2 8.4 kPa, P co 2 9.0 kPa, and serum potassium 4.7 mM). Anaesthesia was induced with propofol 1 mg kg−1, fentanyl 1.5 μg kg−1, and succinylcholine 1 mg kg−1, and the patient was successfully intubated with a videolaryngoscope within 30 s. About 60 s after intubation, heart rhythm converted into a wide complex polymorphic ventricular tachycardia that resulted in cardiac arrest (Fig 1 a). Resuscitation was started immediately with effective chest compressions and ventilation. Rhythm check 2–3 min after arrest confirmed ventricular fibrillation, with defibrillation immediately after one shock of 200 J. A single bolus of epinephrine 1 mg and magnesium sulfate 10 mmol i.v. was administered. A second rhythm check 2–3 min later showed a stable arterial pulse and invasive systolic BP above 110 mm Hg. A wide complex rhythm in association with a narrow complex was identified (Fig 1b). As hyperkalaemia attributable to succinylcholine was immediately suspected, calcium chloride 10 mmol was administered i.v. A blood gas sample (obtained about 4–5 min after the succinylcholine) revealed a potassium of 6.4 mM. Over the next 10 min the patient stabilised, and the ECG normalised to normal sinus rhythm as potassium decreased to 4.2 mM (Fig 1c).

Fig. 1.

Electrocardiograph showing heart rhythm at different times. (a) Heart rhythm at the time of cardiac arrest, (c) heart rhythm at return of spontaneous circulation (potassium 6.4 mM), and (c) heart rhythm after normalisation (potassium 4.2 mM).

The depolarising neuromuscular blocking agent succinylcholine remains the first choice for RSI because of its short and predictable time of onset, and its rapid recovery time. However, as succinylcholine has several adverse effects, the newer non-depolarising agent rocuronium has gained favour in recent years. A Cochrane systematic review of RSI showed that succinylcholine was superior to rocuronium using standard doses (1.0 mg kg−1 and 0.6 mg kg−1, respectively).3 However, this difference disappeared when the rocuronium dose was increased (0.9–1.2 mg kg−1). Recent studies on RSI in pre-hospital and emergency department settings have not shown any difference between succinylcholine and rocuronium.4 , 5 As sugammadex, a reversal agent for rocuronium, is now widely available, the lasting effect of rocuronium compared with succinylcholine is no longer of clinical relevance. There are different national guidelines about the first-choice neuromuscular blocking agent in emergency situations. The UK guidelines have recommended rocuronium as a first-choice agent for RSI in critically ill patients,6 while both the Scandinavian2 and French guidelines7 recommend succinylcholine as the first choice (critical illness is not clearly defined as a specific contraindication in the guidelines).

Blanié and colleagues8 conducted a study on the incidence of hyperkalaemia in ICU patients after receiving succinylcholine. They reported a serum potassium value above 6.5 mM in 11 out of 131 patients (8.4%). Only two patients (1.3%) experienced reversible ventricular arrhythmia. The risk of hyperkalaemia was strongly associated to length of ICU stay, showing an increase after about 2 weeks of immobilisation (an incidence of 37% vs 1% after 16 ICU days). A high incidence of renal dysfunction has been described in COVID-19 patients.9 As a result, serum potassium may be increased, putting them at a higher risk of developing critical hyperkalaemia after receiving succinylcholine. Our patient, despite having renal dysfunction, had a potassium of 4.0 mM days before the intubation, and her highest registered potassium value was 6.4 mM, below the 6.5 mM hyperkalaemia threshold defined as the critical value for cardiac arrhythmia.10 It is highly likely that we missed the peak potassium concentration as the epinephrine administered may have driven the potassium intracellularly. Despite a long ICU stay, our patient had not been diagnosed with critical illness myopathy.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has led to unprecedented shortages of anaesthetic drugs in many countries. This led the Royal College of Anaesthetists to issue guidance on alternative drugs for COVID-19 patients, which included the use of succinylcholine rather than rocuronium for tracheal intubation. In our mind, succinylcholine was the primary cause of cardiac arrest in this patient. We recommend use of rocuronium as the first-choice neuromuscular blocking agent for RSI in critically ill COVID-19 patients.

Declarations of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Martyn J.A., Richtsfeld M. Succinylcholine-induced hyperkalemia in acquired pathologic states: etiologic factors and molecular mechanisms. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:158–169. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200601000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen A.G., Callesen T., Hagemo J.S., Hreinsson K., Lund V., Nordmark J. Scandinavian clinical practice guidelines on general anaesthesia for emergency situations. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54:922–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tran D.T.T., Newton E.K., Mount V.A.H. Rocuronium vs. succinylcholine for rapid sequence intubation: a Cochrane systematic review. Anaesthesia. 2017;72:765–777. doi: 10.1111/anae.13903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.April M.D., Arana A., Pallin D.J. Emergency department intubation success with succinylcholine versus rocuronium: a national emergency airway registry study. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72:645–653. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guihard B., Chollet-Xémard C., Lakhnati P. Effect of rocuronium vs succinylcholine on endotracheal intubation success rate among patients undergoing out-of-hospital rapid sequence intubation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:2303–2312. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.18254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgs A., McGrath B.A., Goddard C. Guidelines for the management of tracheal intubation in critically ill adults. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:323–352. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quintard H., l’Her E., Pottecher J. Experts’ guidelines of intubation and extubation of the ICU patient of French society of anaesthesia and intensive care medicine (SFAR) and French-speaking intensive care society (SRLF): in collaboration with the pediatric association of French-speaking anaesthetists and intensivists (ADARPEF), French-speaking group of intensive care and paediatric emergencies (GFRUP) and intensive care physiotherapy society (SKR) Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9:13. doi: 10.1186/s13613-019-0483-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanié A., Ract C., Leblanc P.E. The limits of succinylcholine for critically ill patients. Anesth Analg. 2012;115:873–879. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31825f829d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213–2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisberg L.S. Management of severe hyperkalemia. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:3246–3251. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818f222b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]