“Allegiance, after all, has to work two ways; and one can grow weary of an allegiance which is not reciprocal.” The British playwright David Hare quoted this line by the American writer James Baldwin in his recent reflections on the UK Government's response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Baldwin's reminder and warning in the context of civil rights in the mid-20th century USA speak now in the pandemic to communities the world over who are unsure of their governments' allegiances to them. The give-and-take relationship between the state and the individual—perhaps best viewed through the lens of what Enlightenment philosophers termed the social contract—is being strained, its inadequacy exposed, and must surely be remade in the midst of this global health and economic crisis.

Governments now ask heavy sacrifices from their people, with around a third of the global population under some form of lockdown. But demonstration that governments are in fact acting to protect the public, for example, through adequately preparing the health system and giving clear advice aimed at saving lives, has been highly variable. Although international comparisons are not straightforward, there are nonetheless encouraging examples of where strong and swift action has succeeded in staving off the worst effects of the virus, be they Germany's quick escalation of testing, New Zealand's elimination strategy, or South Korea's aggressive pursuit of a test-and-trace approach. By contrast, the UK, USA, and Brazil, among others, have been slow to react and haphazard when they did. The serious deficiencies in pandemic planning and response have sparked protests and condemnation and call into question commitment to the most vital interests of the public.

Such failures have too often been accompanied by poor transparency and an ingrained resistance to all forms of accountability. In March, when US President Donald Trump was asked by a reporter if he takes responsibility for the delay in making test kits available, he replied “No, I don't take responsibility at all.” And in April, at a daily COVID-19 briefing when UK Home Secretary Priti Patel was asked twice if she would apologise about the shortage of personal protective equipment for front-line health-care workers, she responded, “I'm sorry if people feel that there have been failings”, in what seemed to be indifference to the sacrifices being made by health-care workers on behalf of the country and its people.

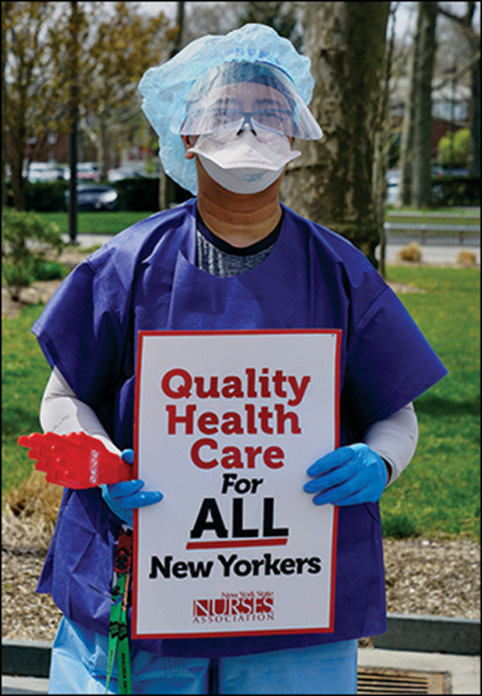

Beyond immediate responses, this pandemic is revealing how a longer-term increase in inequalities and neglect of public services have weakened the ability of societies to deal with external shocks and created new vulnerabilities in a crisis. Racial and ethnic minorities, those with weak employment protections, including migrant workers, and populations without adequate access to affordable health care are among the hardest hit.

However, at the same time, COVID-19 is also overturning core values, norms, and rules that sit at the heart of long-standing market-oriented political agendas. The willingness with which nations have put the brakes on their economies to protect lives, coupled with massive increases in public spending and government debt, particularly by conservative administrations, was inconceivable a few months ago. According to one analysis, as of April 23, a staggering 151 countries have planned, introduced, or adapted a total of 684 social protection measures in response to the pandemic.

Despite important deficiencies in some responses, in many ways the world is witnessing the setting aside of ideology to address the urgent and fundamental need common to all people—the protection of health. So far, the measures taken have been uneven, short-term, and reactive. But it is hard to imagine that when this pandemic is over, the public will be content to go back to the way things were. That it has taken a crisis of this scale to force the recognition that the basic role of a government is to serve and protect its people—that wellbeing has a higher value than gross domestic product—is a shocking demonstration of how the reciprocal rights and responsibilities that form the basis of so many democratic systems have been hollowed out. The kind of societies that are set to emerge from this pandemic is far from clear, but our interconnectedness and interdependence at local, national, and global levels have never been more undeniable. Nor can the importance of well resourced and well prepared health systems continue to be ignored. A renewed and expanded social contract, one with health at the centre, could well be one legacy of COVID-19.

© 2020 Giles Clarke/Getty Images