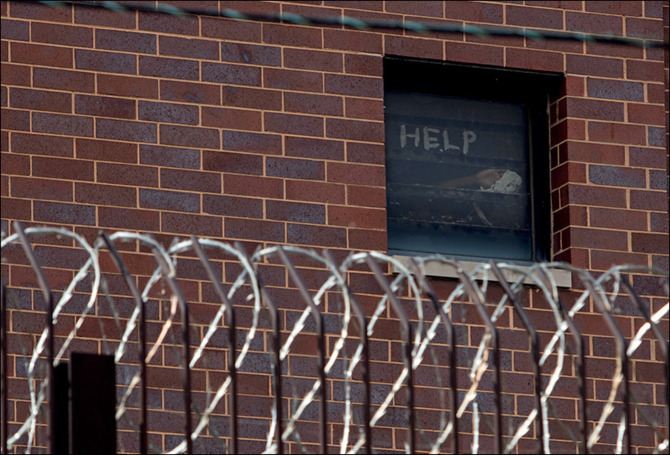

Prisons are a hotspot for COVID-19. In theory, prisoners have the same right to health as anyone else, but the reality is very different. Talha Burki reports.

We will probably never know the extent to which coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has penetrated the world's prisons and detention centres. Testing capacity and the supply of personal protective equipment are already constrained, and inmates are rarely a priority. Nonetheless, at least one prison has done mass testing. The Marion Correctional Institution in Ohio, USA, holds around 2500 detainees. As The Lancet went to press, more than 2000 of them had tested positive for COVID-19.

According to the New York City Board of Correction, there are currently 378 cases of COVID-19 among inmates in the city jails, equating to an infection rate of around 10%. But this does not include those who contracted the virus in custody and have since been released or transferred, or have died. Hundreds of cases have been registered among prison and jail employees, who can obtain testing far more easily than prisoners, including almost 1000 in New York City alone.

“The prisons and jails in the USA that have reported high rates of the coronavirus are the ones who are doing the testing”, points out David Patton, executive director and attorney-in-chief of the Federal Defenders of New York. “It is hard to imagine that the virus is not already rampant throughout the US penal system.” Around 2·2 million individuals are incarcerated in the USA; no other country imprisons as many people.

In the UK, COVID-19 has been detected in the majority of prisons, and at least 15 prisoners and four members of staff have died after being infected. For much of the rest of the world, statistics on infection rates and mortality in prisons are hard to come by, but the danger that COVID-19 poses to such institutions can be discerned from another set of statistics.

The global prison population is estimated at 11 million. At least 124 prisons worldwide exceed their maximum occupancy rates. The Philippines has imprisoned 215 000 people in a system designed for no more than 40 000. 92 000 inmates are thought to be scattered across Myanmar's 100 or so prisons and labour camps, served by a medical staff that is estimated to consist of 30 doctors and 80 nurses. A quarter of inmates in Canada are over the age of 50 years. The UK Justice Secretary, Robert Buckland, reckons that around 1800 prisoners in the UK would be especially susceptible to severe disease were they to contract COVID-19.

The situation in Latin America is particularly worrying. Haiti's prisons are running at 450% occupancy. 773 151 people are imprisoned in Brazil, in a system built to hold 461 026 people. “Conditions in the prisons in South America are ripe for coronavirus to spread”, said Tamara Taraciuk Broner of Human Rights Watch (Buenos Aires, Argentina). “These places are typically very unsanitary and overcrowded and inmates do not always have access to running water.” In such circumstances, regular handwashing and social distancing are impossible to achieve.

“Prisoners share toilets, bathrooms, sinks, and dining halls. They are mostly sleeping in bunk beds; in some countries they sleep crammed together on the floor”, explains Frederick Altice of the Yale School of Medicine (New Haven, CT, USA). “These settings are in no way equipped to deal with an outbreak once it gets in.” If an institution is already operating at far beyond its capacity, it is going to be very difficult to find areas where prisoners with suspected COVID-19 can be isolated. “If a prisoner knows he is going to be put in solitary confinement if he admits to being sick, which is usually a punishment, then there is a heavy disincentive to seek medical attention”, adds Patton.

Prisoners tend to be in worse health than the wider population. “80–90% of people charged with a crime in the USA are too poor to afford legal counsel”, notes Patton. “They have high rates of asthma, diabetes, and smoking”. Prison itself is hardly a healthy environment. A lot of time is spent sitting around, and the food is typically poor quality. And in some places, even poor-quality food is in short supply.

© 2020 Maria Tan/AFP/Getty Images

The occupancy rate for prisons in DR Congo is estimated at 432% of capacity, but food is budgeted on official capacity. That means a maximum of one meal a day. According to the UN peacekeeping mission in DR Congo, at least 60 people died from hunger at Kinshasa's central prison during the first 2 months of 2020. In Niger, those in pretrial detention, a cohort that makes up over half the prison population, are not provided with any food at all. If you cannot rely on family or friends to bring in supplies, you are in serious trouble.

International norms stipulate that prisoners should receive the same standard of health care as the wider community. The reality is very different. “First of all, if you are a prisoner, you cannot just choose to visit the emergency room; you have to go through the officers and that can be a huge obstacle”, said Altice. “Almost no prisons have real hospitals within their walls, and the ratio of clinical staff to prisoners is extremely low; there is no true equivalence of care”.

Sending prisoners for external medical care means seconding officers and transport. Prison administrators can be reluctant to expend such time and resources on a single inmate. “There is both a lack of ability to deal with health issues in-house, because of chronic understaffing, and disincentives to seek outside attention”, said Patton. “It means that prisoners have to be in a very bad state before they get the treatment they need.”

© 2020 Reuters/Jim Vondruska

Matters are further complicated during a time of pandemic, when moving prisoners requires all kinds of additional precautions. “It is very likely that prisoners are not getting medical care or even assessments”, said Altice. “Prisons do not usually have any way to manage patients when they start deteriorating or to triage people at higher risk; prisoners who do get shipped out for treatment are at a much later stage of disease because detection abilities are often limited.”

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, has encouraged governments to release inmates who are especially vulnerable to COVID-19, such as older people, as well as low-risk offenders. “Imprisonment should be a measure of last resort, particularly during this crisis”, she noted, in a statement on March 25, 2020. Experts believe that there is plenty of scope for prisoner releases. In at least 46 countries worldwide, the majority of prisoners have not been convicted of any crime. Rates of pretrial detention are high. A third of Brazil's sizeable prison population, for example, are in pretrial detention. More than one in six prisoners around the world are serving time for possession of drugs for personal use.

“Deincarceration has to be the foremost strategy here”, said Altice. “Several countries, including the USA, have extraordinarily high levels of incarceration. It will certainly be possible to release prisoners and maintain public safety.” He advocates diverting drug offenders to evidence-based treatment programmes. “You can take a lot of people out of the system by doing that, and these are people who are at increased risk of comorbidities such as HIV and hepatitis C, so there is an immediate public health benefit”, said Altice.

Several countries have taken action. Iran announced the release of 85 000 prisoners in March. France and Italy have reduced their prison populations by 10 000 and 6000, respectively. Chile has let out 1300 low-risk offenders, and states across the USA are releasing varying numbers of prisoners. “There is absolutely no doubt that this crisis calls for reducing overcrowding and finding alternatives to prison for people in particular categories, definitely those in pretrial detention for non-violent offences”, Broner told The Lancet. She gave the example of semiopen facilities in Brazil, where prisoners spend the day outside the institution and return in the evening. “That is a huge risk for transmission of COVID-19; it would be better to allow these prisoners to just remain outside”, she said.

UK prisons are running at 107% capacity, which is modest by international standards. The government has pledged to release 4000 prisoners to alleviate the risk of COVID-19 transmission. However, the Prison Governors Association reckons that 15 000 inmates, representing almost a fifth of the prison population, would have to be let out if prisoners were to not share cells. Making a meaningful difference to overcrowding in prison systems elsewhere will require far larger measures. Whether governments are willing to release prisoners in the numbers necessary to truly cut the risk of COVID-19 from tearing through prisons remains to seen.