A brief primer: Air pollution is a complex mixture of gases and particles derived from both human activity (transport, industry etc) and natural sources (windblown dust, sea-salt spray and volatile organic compound emissions from plants). It includes solid and liquid particles (referred to as particulate matter - PM) suspended in the air, that by convention are described based on their aerodynamic diameter, as being on average less than 2.5 μm in diameter (PM2.5), less than 10 μm (PM10), or less than 100 nm (referred to as ultrafines in the air pollution literature, also nanoparticles). These particle ‘fractions’ are compositionally heterogeneous with marked variation between different regions and across time (both throughout the day, as well as over longer time periods, reflecting changes in emission sources) and yet in the literature most publications addressing their adverse effects on health treat them as a uniform entity, adequately summarised as a mass concentration within the air – μm/m3. This reflects the fact that the field has been in large part driven by epidemiological observations linking both long and short-term exposures to air pollutants, to an ever-increasing list of non-communicable diseases at the population level. As particle mass concentration was the metric routinely measured, predominately PM2.5 in the USA and PM10 in Europe, these were the environmental data linked to health records.

Initially the focus was on cardiovascular and respiratory health, using endpoints ranging from a worsening of symptoms, utilisation of health care to early deaths, but as the field has evolved more physiologic endpoints have increasingly been studied, demonstrating that air pollution not only exacerbates end stage disease, but also is involved in their pathogenesis and clinical progression. For example, as covered by the review of Miller in the current issue [1], long-term exposure to ambient PM2.5 has been shown to be robustly associated with an increased risk of premature death from cardiovascular causes (myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke etc), but it has also been shown to be positively associated with established risk factors for cardiovascular disease: vascular endothelial dysfunction [2], hypercholesterolemia [3], hyperglycaemia [4], arrhythmias [5], atherosclerosis [6], hypercoagulability [7], and systemic inflammation [8]. The very fact that the long-term effects of living in areas of high pollution have larger effects on health than short term day-to-day variations in concentrations and pollution episodes underscores the fact that air pollution isn't simply the final coup de grâce hastening the deaths of the aged and vulnerable, it also contributes to the development of disease and the pool of vulnerable individuals within the population.

The impacts globally are significant. The WHO estimates that 9 out of 10 of the world population live in areas failing to meet its health-based guideline for ambient PM2.5 (an annual average of 10 μg/m3) [9], and recent evidence has suggested significant health impacts could extend below this concentration [[10], [11], [12]]. In addition, many people breathe unhealthy levels of particulate pollution in their homes, reflecting exposures to smoke from biomass burning and second-hand tobacco smoke. Combined the global burden of disease from both indoor and outdoor air pollution has been estimated to have contributed to 4,900,000 premature deaths and a total of 147,000,000 disability adjusted life years worldwide in 2017 [13]. Ambient air pollution therefore remains the number one environmental cause of premature mortality and morbidity world-wide. In terms of the breakdown of deaths related to ambient PM2.5 by cause, 48.% were attributable to cardiovascular causes (ischaemic heart disease and stroke), 9.0% cancers of the respiratory system and 36.2% to respiratory infections and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. To place these numbers into context, this annual global loss of life is greater than that associated with parasitic and vector borne disease, HIV infection, cigarette smoking and all forms of violence [14]. These numbers and the ranking of ambient and indoor air pollution combined as having an impact greater than cigarette smoking, can seem counter intuitive; clearly pollution in the air we breathe can't possibly be worse than the noxious cocktail of gases and particles inhaled by a smoker. On an individual level this is true, but not everyone smokes, so the risk is by and large restricted to smokers themselves, whereas we all breathe, and so whilst the risk of air pollution is clearly less, it is experienced to some extent by the entire global population. That population level multiplier matters in terms of the health statistics and ultimately the enormous economic costs attributed to poor air quality.

More than just particle mass: Following the initial observations from the seminal six cities study that both long and short-term exposures to relatively low levels of PM2.5 were associated with an increased risk of early death, predominantly from cardiopulmonary causes [15], a large number of papers have been published globally supporting this initial finding and extending the list of associated diseases to cancer [16], diabetes [17], dementia [18], diseases of the gastrointestinal tract (as reviewed by Feng at al in the current issue [19]), as well as poor birth outcomes [20] and developmental trajectories in children [21]. Whilst overall these associations are consistent across numerous studies, considerable heterogeneity in the effect size estimate exists in the literature, even where data sets have been analysed using similar methods [[22], [23], [24]]. Apart from random variation and differences across study populations, such discrepancies may originate from the use of imperfect indicators of exposure – generally these studies either rely on relatively sparse monitoring data, or models that are at best crude approximations of an individual's exposures. But perhaps, more importantly from a mechanistic perspective, the routine use of ambient PM mass concentration in epidemiological studies ignores sources and constituents, and therefore the biological activity of particles, providing little insight into the causal pathways linking the complex chemistry of the air we breathe to disease aetiology, progression and exacerbation. Some studies have attempted to examine adverse health outcomes against PM components, usually in short term time series studies that examine the relationship between daily variation in constituent concentrations, to daily deaths, or hospital admissions, but these studies remain relatively infrequent in the literature [[25], [26], [27]]. Overall these studies often highlight components associated with combustion processes [25] and road traffic [26,27], even though these often reflect a small proportion of the overall mass. However, even the focus on ambient or indoor particulate matter is an over simplification. Pollutant particles co-exist within the air with other pollutant gases, such as ozone, nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide and a complex cocktail of volatile organic carbon compounds. Many of these gaseous and volatile components are toxic, but their relative contribution to adverse health effects of the population are difficult to dissect out using epidemiological methods because they are often each highly correlated within the air. There is therefore an urgent need for greater investment in comparative toxicology and mechanistic research to clearly define the most harmful components of particulate pollution attributable to their sources, disentangle the relative contribution of gaseous and particulate components, establish adverse outcome pathways that link to specific outcomes to support causal inference and to improve our understanding of differences in the sensitivity and vulnerability of individuals to air pollution.

Why the focus on oxidative stress? There is an increasing scientific consensus that the capacity of inhaled PM and pollutants gases to cause oxidative stress is a primary pathway leading to the observed respiratory and cardiovascular responses seen in exposed populations [28]. Ozone is a powerful oxidant and nitrogen dioxide is a free radical. Airborne particles contain a range of components that are either direct redox catalysts (Fe, Cu, Ni, quinones etc. [29]) or can be metabolised to reactive electrophiles in vivo (PAHs). In addition, non-redox active components can trigger inflammation (LPS) or activate kinase stress pathways by inactivation of phosphatases (exemplified by Zn), even interfere with mitochondrial function (as reviewed by Samet in the current issue [30]) and molecules introduced into the lung on the surface of particles can act as metal chelators, disrupting normal iron homeostasis (Ghio's review article [31]).

Given the compositional complexity of the cocktail of pollutant gases and particles we breathe, oxidative stress has often been framed as an integrative biological pathway to help bridge the causal gap between cause (the initial molecular trigger) and effect (adverse health outcome). Numerous purely chemical/abiotic [32], or in vitro models [33] have been developed to provide an estimate of the capacity of particles and gases to cause oxidative stress in vivo. Whilst these are clearly over simplifications of the in vivo situation and have been subject to criticism, they have shown some useful read across to population level health effects [34,35] and are now broadly accepted as a useful adjunct to compositional information. They do not however substitute for more detailed in vivo mechanistic research.

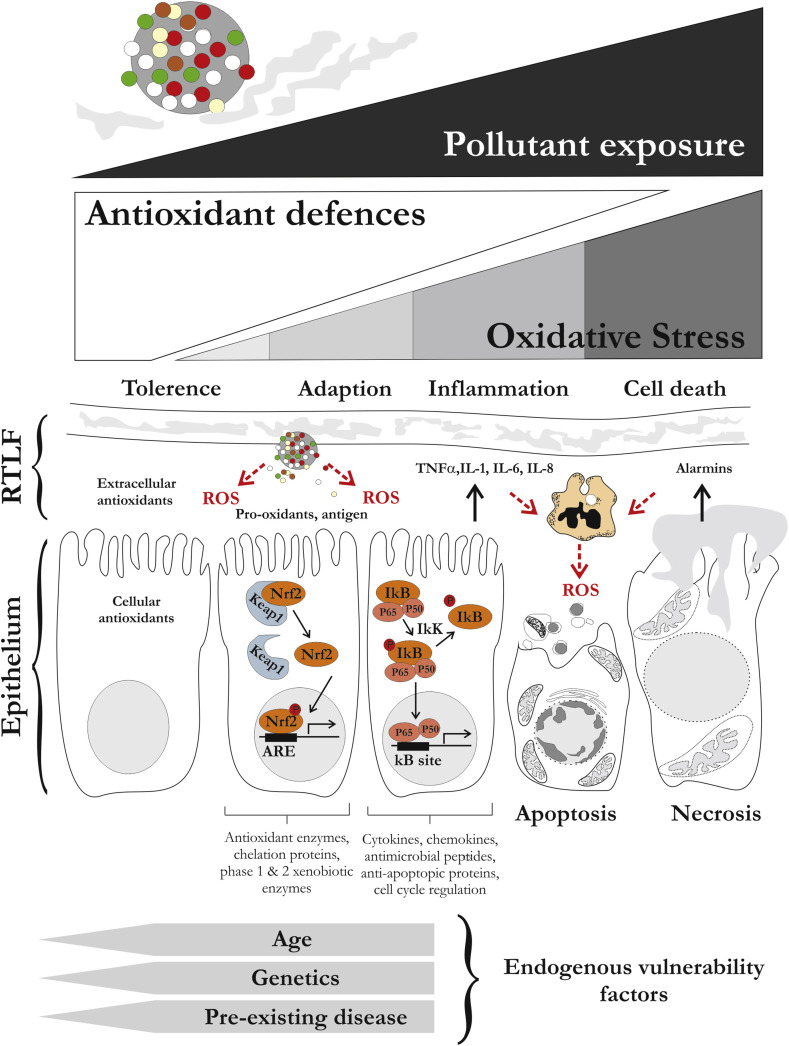

Both in vitro and in vivo research has shown the capacity of pollutant particles and gases to induce redox sensitive pathways and transcription factors [36] mediating responses from early protective adaptations, to the induction of apoptosis. It has been posited that the early adaptive responses mediated via AP-1 and NrF2 (upregulation of enzymes related the antioxidant defence, phase 1 and 2 xenobiotic metabolism and metal homeostasis), together with enrichment of low molecular weight and enzymatic antioxidants at the air-lung interface of the lung, provides the population with some tolerance against inhaled xenobiotics, a fact supported by the evidence that genetic variation in antioxidant genes tracks with increased susceptibility to adverse health effects (reviewed by Fuertes et al. in the current issue [37]). This has led the development of the hierarchical response model to explain the cellular responses to pollutant-induced oxidative stress [38], with responses transitioning from adaptation to inflammation and onward to cell death, with an incrementally increased oxidative burden. It is a simplistic model, as exemplified in Fig. 1 , but useful in that it highlights the importance of the endogenous antioxidant defences and the key role of cellular redox in mediating adverse cellular responses. It also provides a useful framework to consider vulnerability factors within the population, beyond underlying genetic variation, including age and pre-existing disease. For example, the impacts of air pollution tend to be most pronounced in the young and old, where the immune and antioxidant systems are either not fully developed or undergoing age-related declines, and antioxidants defences are known to be depressed, or dysregulated in chronic diseases [39,40].

Fig. 1.

Hierarchical response model illustrating the proposed sequential stages of response to pollutant-induced oxidative stress at the air-lung interface. In this model as the burden of pollution increases the introduction of pro-oxidants and antigens associated with inhaled particles results at oxidative stress, first depleting the endogenous extra and intracellular antioxidant defences, before inducing cellular adaptation by the induction of cytoprotective genes (here illustrated via the induction of NrF2). If these responses are overwhelmed then the model posits that the response transitions to a more damaging inflammatory stage (illustrated via the induction of NFΚB), inducing a second wave of ROS production, reinforcing the oxidative stress within the tissue and driving air way cells towards regulated and unregulated death pathways. Endogenous factors likely to contribute to an increased vulnerability to air pollution induced injury are illustrated.

The hierarchical response model presents particle-induced oxidative stress itself as the initial triggering molecular event for the down stream induction of inflammation and tissue injury, with the induced acute inflammation presenting a secondary a source of reactive oxygens species potentiating the initial injury to the airway epithelium and vascular endothelium. However, there are alternative pathways through which biological, or organic opponents of inhaled particles can trigger inflammation, as exemplified by activation of Toll-like receptors by bacterial or fungal antigens associated with the particle surface [41], or the induction of Th17 signalling through activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor [42]. These pathways and the impact of air pollution on both innate and adaptive immunity are addressed in the review by Glencross et al. [43]. A further limitation of the model is that it focuses on acute responses to pollutant insults, as opposed the long-term responses within tissues, which underlie a considerable burden of air pollution related disease. There are relatively few very long-term in vivo mechanistic studies in the literature, but it is likely that clues from the ‘ageing’ literature may provide insights into how air pollution contributes to increased vulnerability within the population and the development and progression of chronic disease. The contribution of ‘accelerated ageing’ to the progressive loss of lung function from smoking and the development of COPD is a theory that has gained traction in recent years [44] and evidence supporting similar effects related to long term ambient pollutant exposures have been published, examining telomere length as a biomarker of systemic ageing [45]. In this special issue the capacity of air pollution to cause age-related changes in the skin is reviewed by Fussell et al. [46] and it is interesting to speculate whether this represents a correlate to the accelerated aging in other organ systems.

Within this special issue Feng et al. [19] also summarise the literature investigating the impact of air pollution on the gastrointestinal tract and inflammatory bowel diseases. The gut was for a long term ignored by the air pollution community, largely reflecting a pre-occupation with the smaller particles fractions capable of reaching the lower airways and gas exchange regions of the lung. Thus, larger particle fractions transported away from the conducting airways via the mucociliary elevator and subsequently swallowed were not a focus of research. It was thought that their potential content of toxins and toxicants (metals, PAHs etc) would be negligible compared with dietary intakes. This view is now being questioned and the review of Feng is notable for its focus on the impact of air pollution both on the lipidome and the microbiota of the gut, reflecting the emergence of new technological platforms to interrogate the complexity of pollutant, host and commensal community interactions.

What's next: In reflecting on these articles, it is worth considering that there is more atmospheric chemistry, measurement/modelling science and epidemiology in this area, than fundamental mechanism-based research. Reflecting a lack of investment in this area, questions have remained unanswered for decades. There is still no consensus as to what the most harmful components of PM are, in the absence of which policy must focus on reducing all ambient mass, or regulating specific sources, rather than selected components. We still assume that air pollution on a unitary mass basis, is equally toxic everywhere and that there is no safe level. The contemporaneous impacts and synergies between gases, VOCs, compositional heterogeneous particles remain largely unexplored from a toxicological perspective. There are still uncertainties regarding the mode of action of particles and pollutant gases on the cardiovascular system. Whether the adverse effects observed are driven by overspill of inflammatory mediators generated in the lung into the systemic inflammation or mediated by ultrafine particles themselves. These knowledge gaps only continue to grow as air pollution is linked to an ever-expanding list of diseases without a good understanding of the causal pathways driving disease progression, or the exacerbation of symptoms. It is not enough to simply say that air pollution causes this diverse range of responses through oxidative stress and inflammation, simply because these features are so fundamental to all chronic diseases. A much more refined understanding of how particle induced ROS impact on adverse outcome pathways linked to discrete disease endpoints (both short- and long-term) are required and hopefully these articles will act as a call to arms to the free radical biochemistry to engage their expertise in these pressing questions.

Conclusions: In April 2020, in the midst of the global COVID-19 epidemic, whilst the world counts the human costs of the loss of life amongst the elderly, vulnerable and front-line care workers, a focus issue on the health burden and fundamental science of air pollution may somehow seem less important. Yet, it's salient to remember that air pollution in its totality, both ambient and that associated with indoor sources, still represents the single largest environmental risk to global health. Once the current pandemic is past, all the environmental factors that contributed to the global burden of non-communicable disease, diabetes, cardiopulmonary disease will remain, the very factors that have contributed the susceptibility of our aged population at the current time.

References

- 1.Miller M.R. Oxidative stress and the cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020;(19):32275–32280. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.01.004. pii: S0891-5849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills N.L., Törnqvist H., Robinson S.D., Gonzalez M.C., Söderberg S., Sandström T., Blomberg A., Newby D.E., Donaldson K. Air pollution and atherothrombosis. Inhal. Toxicol. 2007;19(suppl 1):81–89. doi: 10.1080/08958370701495170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGuinn L.A., Schneider A., McGarrah R.W., Ward-Caviness C., Neas L.M., Di Q., Schwartz J., Hauser E.R., Kraus W.E., Cascio W.E., Diaz-Sanchez D., Devlin R.B. Association of long-term PM2.5 exposure with traditional and novel lipid measures related to cardiovascular disease risk. Environ. Int. 2019;122:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee S., Park H., Kim S., Lee E.K., Lee J., Hong Y.S., Ha E. Fine particulate matter and incidence of metabolic syndrome in non-CVD patients: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Int. J. Hyg Environ. Health. 2019;222:533–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng B., Song X., Dan M., Yu J., Wang Q., Shu M., Xu H., Wang T., Chen J., Zhang Y., Zhao Q., Wu R., Liu S., Yu J.Z., Wang T., Huang W. High level of source-specific particulate matter air pollution associated with cardiac arrhythmias. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;657:1285–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu S., Yang D., Wei H., Wang B., Huang J., Li H., Shima M., Deng F., Guo X. Association of chemical constituents and pollution sources of ambient fine particulate air pollution and biomarkers of oxidative stress associated with atherosclerosis: a panel study among young adults in Beijing, China. Chemosphere. 2015;135:347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.04.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baccarelli A., Zanobetti A., Martinelli I., Grillo P., Hou L., Giacomini S., Bonzini M., Lanzani G., Mannucci P.M., Bertazzi P.A., Schwartz J. Effects of exposure to air pollution on blood coagulation. J. Thromb. Haemostasis. 2007;5:252–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen R., Li H., Cai J., Wang C., Lin Z., Liu C., Niu Y., Zhao Z., Li W., Kan H. Fine particulate air pollution and the expression of microRNAs and circulating cytokines relevant to inflammation, coagulation, and vasoconstriction. Environ. Health Perspect. 2018;126 doi: 10.1289/EHP1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/02-05-2018-9-out-of-10-people-worldwide-breathe-polluted-air-but-more-countries-are-taking-action site accessed March 2020.

- 10.Crouse D.L., Peters P.A., Hystad P., Brook J.R., van Donkelaar A., Martin R.V., Villeneuve P.J., Jerrett M., Goldberg M.S., Pope C.A., III, Brauer M., Brook R.D., Robichaud A., Menard R., Burnett R.T. Ambient PM2.5, O3, and NO2 exposures and associations with mortality over 16 years of follow-up in the Canadian census health and environment cohort (CanCHEC) Environ. Health Perspect. 2015;123:1180–1186. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stafoggia M., Cesaroni G., Peters A., Andersen Z.J., Badaloni C., Beelen R., Caracciolo B., Cyrys J., de Faire U., de Hoogh K., Eriksen K.T., Fratiglioni L., Galassi C., Gigante B., Havulinna A.S., Hennig F., Hilding A., Hoek G., Hoffmann B., Houthuijs D., Korek M., Lanki T., Leander K., Magnusson P.K., Meisinger C., Migliore E., Overvad K., Ostenson C.G., Pedersen N.L., Pekkanen J., Penell J., Pershagen G., Pundt N., Pyko A., Raaschou-Nielsen O., Ranzi A., Ricceri F., Sacerdote C., Swart W.J., Turunen A.W., Vineis P., Weimar C., Weinmayr G., Wolf K., Brunekreef B., Forastiere F. Long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and incidence of cerebrovascular events: results from 11 European cohorts within the ESCAPE project. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014;122:919–925. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cesaroni G., Forastiere F., Stafoggia M., Andersen Z.J., Badaloni C., Beelen R., Caracciolo B., de Faire U., Erbel R., Eriksen K.T., Fratiglioni L., Galassi C., Hampel R., Heier M., Hennig F., Hilding A., Hoffmann B., Houthuijs D., Jöckel K.H., Korek M., Lanki T., Leander K., Magnusson P.K., Migliore E., Ostenson C.G., Overvad K., Pedersen N.L., J J.P., Penell J., Pershagen G., Pyko A., Raaschou-Nielsen O., Ranzi A., Ricceri F., Sacerdote C., Salomaa V., Swart W., Turunen A.W., Vineis P., Weinmayr G., Wolf K., de Hoogh K., Hoek G., Brunekreef B., Peters A. Long term exposure to ambient air pollution and incidence of acute coronary events: prospective cohort study and meta-analysis in 11 European cohorts from the ESCAPE Project. BMJ. 2014;348:f7412. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.GBD 2017 Risk Factor Collaborators, Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1923–1994. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32225-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lelieveld J., Pozzer A., Pöschl U., Fnais M., Haines A., Münzel T. Loss of life expectancy from air pollution compared to other risk factors: a worldwide perspective. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dockery D.W., Pope C.A., 3rd, Xu X., Spengler J.D., Ware J.H., Fay M.E., Ferris B.G., Jr., Speizer F.E. An association between air pollution and mortality in six U.S. cities. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993;329:1753–1759. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312093292401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Møller P., Folkmann J.K., Forchhammer L., Bräuner E.V., Danielsen P.H., Risom L., Loft S. Air pollution, oxidative damage to DNA, and carcinogenesis. Canc. Lett. 2008;266:84–97. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim C.C., Thurston G.D. Air pollution, oxidative stress, and diabetes: a life course epidemiologic perspective. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2019;19:58. doi: 10.1007/s11892-019-1181-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peters R., Ee N., Peters J., Booth A., Mudway I., Anstey K.L. Air pollution and dementia: a systematic review. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019;70(suppl 1):S145–S163. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng J., Cavallero S., Hsiai T., Li R. Impact of air pollution on intestinal redox lipidome and microbiome. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020;(19):32274–32279. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.12.044. pii: S0891-5849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith R.B., Fecht D., Gulliver J., Beevers S.D., Dajnak D., Blangiardo M., Ghosh R.E., Hansell A.L., Kelly F.J., Anderson H.R., Toledano M.B. Impact of London's road traffic air and noise pollution on birth weight: retrospective population-based cohort study. BMJ. 2017;359:j5299. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gauderman W.J., Vora H., McConnell R., Berhane K., Gilliland F., Thomas D., Lurmann F., Avol E., Kunzli N., Jerrett M., Peters J. Effect of exposure to traffic on lung development from 10 to 18 years of age: a cohort study. Lancet. 2007;369:571–577. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bell M.L., Samet J.M., Dominici F. Time-series studies of particulate matter. Annu. Rev. Publ. Health. 2004;25:247–280. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.102802.124329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katsouyanni K., Touloumi G., Samoli E., Gryparis A., Le Tertre A., Monopolis Y., Rossi G., Zmirou D., Ballester F., Boumghar A., Anderson H.R., Wojtyniak B., Paldy A., Braunstein R., Pekkanen J., Schindler C., Schwartz J. Confounding and effect modification in the short-term effects of ambient particles on total mortality: results from 29 European cities within the APHEA2 project. Epidemiology. 2001;12:521–531. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200109000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samet J.M., Dominici F., Curriero F.C., Coursac I., Zeger S.L. Fine particulate air pollution and mortality in 20 U.S. cities, 1987- 1994. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;343:1742–1749. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012143432401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou J., Ito K., Lall R., Lippmann M., Thurston G. Time-series analysis of mortality effects of fine particulate matter components in Detroit and Seattle. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011;119:461–466. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bell M.L., Ebisu K., Leaderer B.P., Gent J.F., Lee H.J., Koutrakis P., Wang Y., Dominici F., Peng R.D. Associations of PM₂.₅ constituents and sources with hospital admissions: analysis of four counties in Connecticut and Massachusetts (USA) for persons ≥ 65 years of age. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014;122:138–144. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1306656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atkinson R.W., Samoli E., Analitis A., Fuller G.W., Green D.C., Anderson H.R., Purdie E., Dunster C., Aitlhadj L., Kelly F.J., Mudway I.S. Short-term associations between particle oxidative potential and daily mortality and hospital admissions in London. Int. J. Hyg Environ. Health. 2016;219:566–572. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly F.J., Fussell J.C. Linking ambient particulate matter pollution effects with oxidative biology and immune responses. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015;1340:84–94. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly F.J., Mudway I.S. Protein oxidation at the air-lung interface. Amino Acids. 2003;25:375–396. doi: 10.1007/s00726-003-0024-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samet J.M., Chen H., Pennington E.R., Bromberg P.A. Non-redox cycling mechanisms of oxidative stress induced by PM metals. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019;(19):31249–31253. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.12.027. pii: S0891-5849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghio A.J., Soukup J.M., Dailey L.A., Madden M.C. Air pollutants disrupt iron homeostasis to impact oxidant generation, biological effects, and tissue injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020;(19):31669–31677. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.02.007. pii: S0891-5849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janssen N.A., Strak M., Yang A., Hellack B., Kelly F.J., Kuhlbusch T.A., Harrison R.M., Brunekreef B., Cassee F.R., Steenhof M., Hoek G. Associations between three specific a-cellular measures of the oxidative potential of particulate matter and markers of acute airway and nasal inflammation in healthy volunteers. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015;72:49–56. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2014-102303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang H., Haghani A., Mousavi A.H., Cacciottolo M., D'Agostino C., Safi N., Sowlat M.H., Sioutas C., Morgan T.E., Finch C.E., Forman H.J. Cell-based assays that predict in vivo neurotoxicity of urban ambient nano-sized particulate matter. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019;145:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atkinson R.W., Samoli E., Analitis A., Fuller G.W., Green D.C., Anderson H.R., Purdie E., Dunster C., Aitlhadj L., Kelly FJ F.J., Mudway I.S. Short-term associations between particle oxidative potential and daily mortality and hospital admissions in London. Int. J. Hyg Environ. Health. 2016;219:566–572. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weichenthal S., Lavigne E., Evans G., Pollitt K., Burnett R.T. Ambient PM2.5 and risk of emergency room visits for myocardial infarction: impact of regional PM2.5 oxidative potential: a case-crossover study. Environ. Health. 2016;15:46. doi: 10.1186/s12940-016-0129-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pourazar J., Mudway I.S., Samet J.M., Helleday R., Blomberg A., Wilson S.J., Frew A.J., Kelly F.J., Sandström T. Diesel exhaust activates redox-sensitive transcription factors and kinases in human airways. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2005;289:L724–L730. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00055.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuertes E., van der Plaat D.A., Minelli C. Antioxidant genes and susceptibility to air pollution for respiratory and cardiovascular health. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020;(19):32388–32393. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.01.181. pii: S0891-5849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xia T., Kovochich M., Nel A. The role of reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress in mediating particulate matter injury. Clin. Occup. Environ. Med. 2006;5:817–836. doi: 10.1016/j.coem.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choudhury G., MacNee W. Role of inflammation and oxidative stress in the pathology of ageing in COPD: potential therapeutic interventions. COPD. 2017;14:122–135. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2016.1214948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goven D., Boutten A., Leçon-Malas V., Marchal-Sommé J., Amara N., Crestani B., Fournier M., Lesèche G., Soler P., Boczkowski J., Bonay M. Altered Nrf2/Keap1-Bach1 equilibrium in pulmonary emphysema. Thorax. 2008;63:916–924. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.091181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cevallos V.M., Díaz V., Sirois C.M. Particulate matter air pollution from the city of Quito, Ecuador, activates inflammatory signaling pathways in vitro. Innate Immun. 2017;23:392–400. doi: 10.1177/1753425917699864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Driscoll C.A., Gallo M.E., Hoffmann E.J., Fechner J.H., Schauer J.J., Bradfield C.A., Mezrich J.D. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) present in ambient urban dust drive proinflammatory T cell and dendritic cell responses via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) in vitro. PloS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glencross D.A., Ho T.R., Camiña N., Hawrylowicz C.M., Pfeffer P.E. Air pollution and its effects on the immune system. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020;(19):31521–31527. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.01.179. pii: S0891-5849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mercado N., Ito K., Barnes P.J. Accelerated ageing of the lung in COPD: new concepts. Thorax. 2015;70:482–489. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martens D.S., Nawrot T.S. Ageing at the level of telomeres in association to residential landscape and air pollution at home and work: a review of the current evidence. Toxicol. Lett. 2018;298:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2018.06.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fussell J.C., Kelly F.J. Oxidative contribution of air pollution to extrinsic skin ageing. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020;(19):31498–31504. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.11.038. pii: S0891-5849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]