Abstract

The evolution of therapeutics for and management of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) infection has shifted it from predominately manifesting as a severe, acute disease with high mortality to a chronic, controlled infection with a near typical life expectancy. However, despite extensive use of highly active antiretroviral therapy, the prevalence of chronic widespread pain in people with HIV remains high even in those with a low viral load and high CD4 count. Chronic widespread pain is a common comorbidity of HIV infection and is associated with decreased quality of life and a high rate of disability. Chronic pain in people with HIV is multifactorial and influenced by HIV-induced peripheral neuropathy, drug-induced peripheral neuropathy, and chronic inflammation. The specific mechanisms underlying these three broad categories that contribute to chronic widespread pain are not well understood, hindering the development and application of pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches to mitigate chronic widespread pain. The consequent insufficiencies in clinical approaches to alleviation of chronic pain in people with HIV contribute to an overreliance on opioids and alarming rise in active addiction and overdose. This article reviews the current understanding of the pathogenesis of chronic widespread pain in people with HIV and identifies potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets to mitigate it.

Keywords: HIV, chronic widespread pain, peripheral neuropathy, peripheral immune cells, inflammation, HIV-1 proteins

Introduction

The prevalence estimates of chronic pain associated with human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) infection vary widely, ranging from 25% to 90% of people with HIV (PWH) depending on the cohort.1–3 The prevalence of pain associated with end-stage patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is not unlike that of end-stage patients with cancer,4 yet far fewer studies have focused on mechanisms of pain related to HIV and AIDS than cancer. The current review seeks to consolidate and review the existing body of literature regarding the etiology of chronic pain in PWH. The review is focused around three key mechanistic areas of current scientific interest: (1) host immune cells, (2) viral proteins, and (3) antiviral therapy.

Pain physiology

A conscious perception of pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage.5 A common framework to facilitate our understanding of pain delineates four key events: sensory transduction, transmission, perception, and modulation. A noxious stimulus or tissue injury causes release of allogenic chemical mediators of pain and inflammation and neurotransmitters including interleukins (ILs), neuropeptides (substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide), prostaglandins, histamine, bradykinin, glutamate, and norepinephrine.6 These mediators stimulate first-order peripheral afferent neurons to generate an action potential in a process known as sensory transduction. Sensory information is then propagated and transmitted centrally via synaptic contact with second-order neurons within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Spinal projection neurons ascend via the spinothalamic tract to the thalamus, where third-order neurons then transmit information to limbic regions and somatosensory cortex where pain is consciously perceived. The spinal dorsal horn is a critical site of modulation, where incoming signals may be inhibited or excited via local (segmental or propriospinal) circuits or by descending input from supraspinal structures.

Acute pain serves a physiological purpose to alert the organism to imminent or ongoing tissue damage or injury and elicit a response for self-preservation. However, chronic pain can occur even in the absence of a noxious stimulus, such as tissue damage, and is characterized by changes in the way pain-related signals are processed and modulated. Peripheral injury and inflammation lead to local increases in chemical mediators that lower activation thresholds and increase responsiveness in peripheral nerves, where transduction occurs (peripheral sensitization). Intense or prolonged input to the central nervous system (CNS) as well as factors that influence pain modulation (e.g., stress) can further lead to amplification of nociceptive signaling within the spinal dorsal horn and brain (central sensitization). The consequences of these sensitization processes are the hyperalgesia and/or allodynia that are characteristic of chronic pain.

Epidemiology of chronic pain in HIV

Chronic pain, defined as lasting at least three months and not associated with ongoing tissue injury,7 is a burdensome comorbidity of HIV infection. In PWH, chronic pain is associated with a high rate of disability and decreased quality of life.8 In particular, the prevalence of chronic pains at more than one anatomical site (i.e., chronic widespread pain (CWP)) in PWH ranges from 25% to 90%.2,3,9,10 As with other chronic pains, women are more likely to have chronic HIV-related pain and are at a higher risk for under treatment of their pain.11 Chronic pain associated with HIV includes regional and widespread musculoskeletal pain3 of neuropathic and inflammatory nature.10,12,13 The primary sites of HIV-related CWP are the joints, head, legs, and back,14,15 with 53.7% of PWH rating their pain as severe.3 HIV-related CWP leads to serious health consequences, including up to 10× greater odds of functional impairment.9 Disproportionately high rates of chronic pain in PWH have been attributed to virus- and drug-induced peripheral neuropathies16,17 and chronic, non-neuropathic inflammation.12 Despite an increase in awareness that pain is a significant problem for PWH, including the creation of an International Task Force on Pain and AIDS in 1994 to address this problem, the prevalence of HIV-related pain since the 1980s has not diminished. This underscores the fact that highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and current pain management strategies are not sufficient to address the individual and socioeconomic burden of pain in PWH.

Opioid use in PWH with CWP

Despite a lack of evidence demonstrating their long-term efficacy,18,19 prescription opioids remain an essential element of long-term pain management in PWH. Their use as a chronic therapy brings a complex set of issues and risks both in the general population and in PWH. In the general population, the epidemic of prescription opioid misuse has resulted in a transition to injectable forms of illicit opioids (e.g., heroin), with almost 80% of new heroin users reporting prior prescription opioid abuse.20 Within the HIV patient population, those with a history of illicit substance abuse are statistically more likely to report pain.21 Furthermore, comorbid illicit substance abuse increases pain symptoms in PWH22 despite physician-prescribed pharmaceutical pain treatment, underscoring the inadequacy of current pain management strategies in this population.23 PWH with a history of opioid dependence often need higher doses of opioids to treat acute bouts of pain due to the development of tolerance,24,25 and long-term opioid use leads to depression and may paradoxically worsen chronic pain.26 From a public health perspective, there is an increased chance of transmitting and acquiring hepatitis B and C due to opioid use-related engagement in high risk behaviors.27 Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop novel, targeted therapeutic strategies and minimize the use of opioids in PWH.

Mechanisms of chronic pain in HIV

Peripheral immune cells

The peripheral immune system may play an important role in the development of HIV-associated hypersensitivity. The activation of pro-inflammatory pathways in peripheral immune cells in adaptive response to infection with the HIV-1 virus may come at the cost of changes in afferent nociceptive signaling that contribute to the development of hypersensitivity and pain-related syndromes. As is typical with viral infection or peripheral tissue injury, there is an early activation and proliferation of resident macrophages with concurrent recruitment and inflammatory specialization of infiltrative macrophages. Macrophages are the earliest and most prolific of the infiltrating cells observed with nerve injury and neuro-inflammation and, importantly, this pattern is conserved across various preclinical models of neuropathy.28 Injury leads to macrophage release of matrix metalloproteases that further contribute to recruitment and infiltration of immune cells to the initial site of damage.29 This peripheral inflammatory milieu causes neuronal damage as well as direct stimulation of nociceptors with signal amplification leading to glial cell activation, thus provoking an innate, macrophage-driven immune response more proximally within dorsal root ganglia (DRG), where primary afferent somata are located.29,30

Recent studies have shown that during HIV-1 infection in humans and simian immune virus (SIV) infection in macaques, monocyte/macrophages traffic to the DRG and cause damage resulting in peripheral neuropathy.31–34 Hahn et al. showed that the exposure of supernatant from macrophages infected with HIV-1 strains to dissociated, cultured human DRG neurons induced somata and axonal mitochondrial dysfunction and neurite retraction.32 Treatment with antioxidants rescued the neuronal cell body but not the axon from the toxic mitochondrial effects of the culture supernatants.32 Laast et al. demonstrated that the SIV-infected macaques had significantly lower C-fiber conduction velocity in sural nerves than uninfected animals, and the magnitude of decline correlated strongly with extent of DRG macrophage infiltration.33 Lakritz et al. further demonstrated that the loss of intraepidermal nerve fiber density during SIV peripheral neuropathy is mediated by monocyte activation and elevated monocyte chemotactic proteins.35

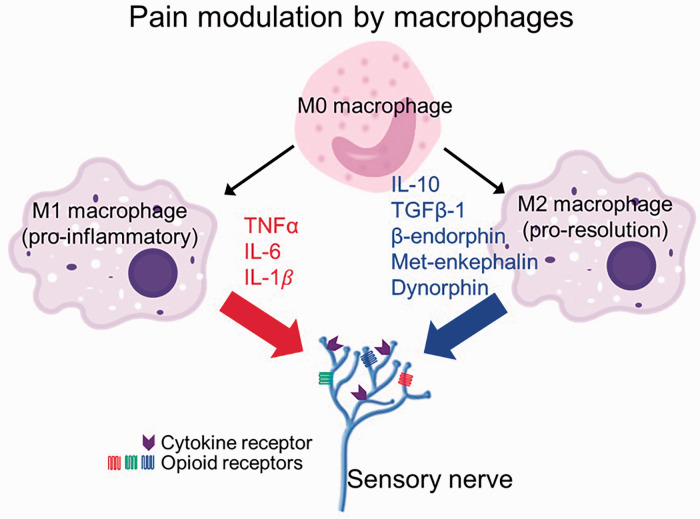

Once activated, resident macrophages release damage-associated molecular patterns that serve to further activate and recruit immune cells, including T helper type 1 (Th1) cells. Th1 cells release the cytokine interferon-gamma capable of instigating the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 (JAK-STAT-1) signaling pathway and inducing activation of the pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotype.28,36 Pro-inflammatory macrophages express inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, which enhance local neuro-inflammation, play a role in establishing a neuropathic pain state, and lead to peripheral and central sensitization (Figure 1).28,30 Conversely, Th2 cells release IL-4 and IL-13 that promote the development of the pro-resolution, macrophage phenotype characterized by expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (Figure 1). The ratio of pro-resolution to anti-inflammatory macrophages appears important in neuropathic pain, and pharmacologic attempts to modulate this balance have been reviewed recently.28 In a recent study of PWH who self-reported chronic pain, plasma levels of IL-1β were significantly higher than in individuals without chronic pain.12 Measurement of cytokines in PWH demonstrated that the ratios of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α/IL-4, IL-6/IL-4, and interferon-γ/IL-10) were higher in PWH with peripheral neuropathy.37 Moreover, overexpressing IL-10 has been shown as a therapeutic strategy to decrease TNF-α and increase mechanical pain threshold in rats with neuropathic pain.38

Figure 1.

Pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages release pro-algetic cytokines, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. However, pro-resolution M2 macrophages release anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-10, and anti-algetic endogenous opioid peptides Met-enkephalin, dynorphin A, and β-endorphin. IL: interleukin; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; TGF: transforming growth factor.

In addition to their direct effects on inflammation and sensitization, macrophages are important for the recruitment of other immune cells. Macrophages guide neutrophils and lymphocytes to the site of injury through chemokine signaling,29 and together with Schwann cells synergistically contribute to a positive feedback loop of cellular recruitment and neuro-inflammation.28 The infiltration of lymphocytes into DRG and spinal cord has been demonstrated in an LP-BM5, a murine retroviral isolate, infected murine AIDS (MAID) model.39 Specifically, these immune cells released redox-active species into DRG neurons, resulting in oxidative damage and increased mechanosensitivity of the hindpaw.39 The role of macrophages in neuropathic pain is further emphasized by demonstration of reduced mechanical hypersensitivity and Wallerian degeneration in rats after depletion of macrophages with dichloromethylene diphosphonate-containing liposomes.40 Other animal models limiting macrophage recruitment have also demonstrated a corresponding reduction in neuronal degeneration and hyperalgesia.41

CWP has commonly been attributed to both diffuse inflammatory processes and to failed pain inhibitory systems.42 Mechanisms of these endogenous inhibitory systems have included both central mechanisms and those involving peripheral actions of opioids, particularly in deep tissues.43 Macrophages are a rich source of opioid peptides44–47 that inhibit inflammatory pain by binding peripheral opioid receptors.48–50 Compared to pro-inflammatory (M1 phenotype) macrophages, pro-resolution (M2 phenotype) macrophages contain and release higher amounts of opioid peptides (met-enkephalin (ENK), dynorphin A (DYN), and β-endorphin (END)) and can therefore produce analgesia51 (Figure 1). Preclinical adoptive transfer of M2 cells at the site of injury has been shown to reduce mechanical hypersensitivity and is reversed by the administration of naloxone methiodide,51 a peripherally acting opioid receptor antagonist. Similarly, promoting the polarization of naive macrophages toward the M2 phenotype52,53 has been shown to attenuate postoperative pain54 and decrease tactile hypersensitivity.55 Lakritz et al. demonstrated that the number of M1-like monocytes/macrophages correlated with more severe DRG histopathology and loss of intraepidermal nerve fibers in SIV peripheral neuropathy.56 In the context of HIV infection, it must be emphasized that macrophages play a crucial role as viral reservoirs, especially in the periphery. Polarization of macrophages to the M1 phenotype appears to help keep viral replication in check to some extent and to facilitate immune system clearance of infected cells.57

Envelope glycoprotein gp120

HIV-1 infection generates direct neuronal injury, instigates processes that result in inflammatory neuronal degeneration, and causes a generalized inflammatory milieu that contributes to pain independent of the concurrent cellular destruction. The viral envelop glycoprotein, gp120, plays a key role in viral entry and has attracted considerable attention for its role in contributing to neurotoxicity as well as establishing an inflammatory state. HIV gp120 facilitates viral entry through CD4-receptor binding and membrane fusion, with CCR5 and C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) functioning as coreceptors on the target cell. In many preclinical studies, HIV gp120 has been linked to mechanical hyperalgesia58 and importantly can exert an effect on cells even in the absence of cellular viral infection59,60 as direct neuronal infection is rare.

HIV gp120 binding to CCR5 has been linked to neurotoxicity and upregulation of pro-inflammatory gene expression in macrophages consistent with an M1 phenotypic state, demonstrating the potential role of viral immune modulation in the generation of pain.61 HIV gp120 ligation of CXCR4 on Schwann cells leads to TNF-α/TNF receptor-1 (TNFR-1) neuronal apoptosis by initiating the release of Regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) and causing production of TNF-α within the DRG.62 This effect was noted in the absence of macrophages detected in DRG cultures, demonstrating the ability of gp120 to potentially cause downstream neurotoxicity, axonal degeneration, and inflammatory mediator release independent of the host immune response. Zheng et al. further explored the interplay between gp120, TNF-α, and microglia in modulating mechanical allodynia. They found that in vivo application of gp120 to rat sciatic nerve caused mechanical allodynia, increased TNF-α mRNA expression in the lumbar spinal dorsal horn, and that colocalization implicated microglia in the release of TNF-α and increased TNF-α within the DRG of rats after gp120 application.63 Importantly, these investigators were able to reverse the allodynia with a glial cytokine inhibitor, with a soluble TNF receptor, and by administering siRNA for TNF-α, drawing a direct linkage between the viral protein, glial cells, and a phenotype consistent with neuropathic pain.63

Yi et al. further elucidated the mechanisms downstream of TNF-α involved in gp120-induced neuropathic pain.64 Again using HIV gp120 application onto the rat sciatic nerve, they demonstrated that gp120 increased TNF-α, TNFR-1, mitochondrial superoxide, phosphorylation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein (CREB), and levels of phosphorylated cytosine-cytosine-adenosine-adenosine-thymidine (CCAAT)/enhancer binding protein-β (pC/EBPβ) in the ipsilateral spinal dorsal horn.64By sequential inhibition of the above-mentioned individual components, the authors demonstrated that the gp120-induced neuropathic pain was mediated by the following pathway: TNF-α/TNFR-1—mitochondrial superoxide—pCREB—pC/EBPβ.64 Other studies have also shown that C/EBPβ in DRG is involved in neuropathic pain and is a potential target for ameliorating neuropathic pain.65 Similarly, increase in phospho-CREB levels have been reported in pain-positive HIV patients.66 The gp120-induced mitochondrial superoxide production has been shown to be mediated by an increase in mitochondrial fission protein, dynamin-related protein-1 (Drp-1).67 The inhibition of Drp-1 reduced mitochondrial reactive species production and gp120-related neuropathic pain in rats.67 Moreover, gp120 has been shown to directly disrupt microtubule transport of mitochondria within the neuron, providing yet another mechanism by which cellular function is disrupted and intracellular energy deficits could result in axonal degeneration and a consequent neuropathic phenotype.68

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) plays a critical role in acute pain signaling in the DRG as well as in the development and maintenance of chronic pain.69,70 ATP activates purinergic P2 receptors, classified into (1) P2X receptors, which are ionotropic ligand-gated ion channels, and (2) P2Y receptors, which are metabotropic G-protein-coupled receptors. Seven P2X receptors (P2X1-7) and eight P2Y receptors (P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, P2Y11, P2Y12, P2Y13, and P2Y14) have currently been recognized.71,72 Several P2 receptors have been implicated in gp120-induced hypersensitivity. In two recent studies, Yi and colleagues studied the role of P2Y12 in a rat model of neuropathic pain induced by gp120 combined with the antiretro viral drug, ddC (2′,3′-dideoxycytidine). They found that gp120 + ddC treatment increased the expression of P2Y12 receptor in DRG. In contrast, genetically reducing P2Y12 receptor expression in DRG reduced the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and relieved mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in gp120 + ddC-treated rats.73 Another study demonstrated elevated expression of P2X3 protein in DRG in gp120-treated rats that correlated with neuropathic hypersensitivity sensitive to pharmacological antagonism of P2X3.74,75 Upregulation of DRG expression of P2X7 has also been demonstrated following gp120 treatment. Subsequent treatment with the P2X7 antagonist, brilliant blue G, decreased hyperalgesia and P2X7 expression, and also decreased IL-1β and TNF-α receptor expression while increasing IL-10 in gp120-treated DRG.76 Together, these provide compelling evidence that the activation and upregulation of P2 receptors in DRG mediate grp120-induced pain and are therefore targets for HIV-associated pain.

Finally, important interactions between gp120 and other mediators of chronic pain in HIV have been outlined. Using two neuropathic pain models to investigate the interplay between HAART neurotoxicity and gp120, the combined administration of both HAART and gp120 resulted in evidence of neuropathic pain greater than HAART alone, suggesting either an additive or synergistic effect.77 In a more recent study, Takahashi et al. examined the interactions between HIV gp120 and opioid exposure. The group found that intrathecal administration of gp120 and morphine for five days induced greater persistent mechanical allodynia relative either gp120 or morphine alone.78 Together, the above-mentioned studies show that gp120-initiated macrophage activation and inflammatory cytokine release in the DRG and peripheral nerves along with direct axonal damage and neuronal apoptosis are likely concurrently contributing to the effects seen in animal models and individuals with HIV sensory neuropathy (HIV-SN).79,80

Trans-activator of transcription (Tat)

Trans-activator or transcription (Tat) is the first protein produced and released by infected host cells after HIV infection. It continues to be expressed from reservoir host cells, despite HAART and persists within CNS tissues contributing to neuro-inflammation and consequent neurotoxicity.81,82 Tat causes neurotoxicity through DNA double strand breaks83 and via N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated alterations in intracellular calcium hemostasis84–86 and glutamate excitotoxicity.87 Its expression is associated with microglial priming and IL-1β release88 and it activates nuclear factor-kB,89 factors that lead to increased expression of inflammatory cytokines including IL-6 and TNF-α. While much initial attention has focused on the role of Tat neurotoxicity within the CNS leading to neurocognitive dysfunction, it may also contribute to HIV-SN through similar mechanisms. Recently, Tat mRNA expression was noted in DRG and skin samples after induction of its expression in mice, with an associated reduction in nerve fiber density and concurrent progressive mechanical hypersensitivity without motor impairment.90 This is consistent with the clinical syndrome of HIV-SN, providing evidence that Tat may be integral in HIV-SN pathogenesis. Moreover, Tat has been shown to induce marked hyperexcitability and apoptosis of primary DRG neurons.91

Again in consideration of interactions between HIV-relevant proteins and opioids, Tat has been implicated in modification of opioid tolerance and physical dependence. Fitting et al. demonstrated that the induction of Tat mRNA in mice corresponded to a significant loss of morphine-induced antinociception, as assessed by the tail-flick test.92 In a second study by the same group, the induction of Tat in mice resulted in increased tolerance for morphine, based on nociceptive assays and locomotor activity.93 Furthermore, the induction of Tat resulted in reduced physical dependence to chronic morphine exposure.93 Importantly, chronic Tat expression is noted in immune cells despite pharmacological therapy and irrespective of viral load, providing a challenging but potentially promising target for future therapeutic interventions.

Viral protein R (Vpr)

Viral protein R (Vpr) is observed early after HIV infection. It initially helps mediate viral replication and then is synthesized and exported later in the viral life cycle where it facilitates viral infection of macrophages and monocytes. As a highly conserved gene with a crucial role in viral infection, replication, and spread, it is an enticing therapeutic target.94 Detectable levels of Vpr increase in late stage disease in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid of PWH. As an extracellular protein, Vpr triggers apoptotic pathways, stimulates inflammatory cytokine release, and interferes with ATP production leading to accumulation of reactive oxygen species and increasing oxidative stress.95 Similar to gp120, the role of Vpr in CNS symptoms and HIV-related neurocognitive changes is a common focus in the literature, but scarce prior work has delved into the potential of its neurotoxicity in the context of neuropathic pain. In exception, Acharjee et al.96 sought to examine the presence of peripheral Vpr and the role it may play in establishing neuropathic pain in PWH. They reported Vpr expression in DRG autopsy specimens from HIV-infected individuals. Furthermore, by establishing an HIV infection in human DRG cultures, they were able to demonstrate Vpr expression as well as evidence of neuronal damage and innate immune system activation.96 Mechanistically, they found increased cytosolic calcium levels in human and rat DRG neurons exposed to Vpr with an increase in neuronal excitability. They further demonstrated in a transgenic model expressing the Vpr gene on an immune-deficient the presence of mechanical allodynia associated with inflammatory cytokine dysregulation. In sum, these findings effectively link Vpr to both direct and indirect mechanisms of neuronal toxicity.96

Antiretroviral drugs

The development of pharmacologic agents to treat HIV infection and the widespread implementation of HAART has significantly reduced HIV-related mortality, thereby changing the dynamic of the disease process and reframing HIV as a chronic entity no longer merely confined to an acute, severe condition. The long-term requirement for viral suppression by antiretroviral agents (ARVs) exposes PWH to both acute and chronic side effect profiles of ARVs. One common side effect of ARV is peripheral neuropathic pain. The determination whether viral proteins or ARV therapy are responsible for pathological basis of HIV-SN is often based upon the timing of ARV institution, as the etiology of the neuropathy is generally indistinguishable based on clinical symptoms.97 ARV toxic neuropathy is also characterized by axonal loss and axonopathy as has been demonstrated in models developed in an attempt to isolate the toxic effects of these agents from the confounding neurotoxicity of the HIV viral proteins described above.79

The nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs, including stavudine, zalcitabine, zidovudine, and didanosine) are particularly associated with the development of HIV-SN. Zalcitabine, although rarely used clinically today, has proven particularly useful in the model development for the study of neurotoxicity in vitro and in vivo.79 The preponderance of evidence in both animal and human studies seems to implicate NRTI-induced mitochondrial dysfunction as a pivotal step leading to disruptions in calcium homeostasis and a pro-apoptotic state.79 In a model of NRTI-induced neuropathy, Ferrari and Levine98 found that inhibitors of the electron transport chain, oxidative stress, and caspase signaling were able to antagonize the mechanical hyperalgesia that occurred after NRTI exposures. Furthermore, they found that the combination of alcohol consumption (a known comorbid risk factor for HIV-SN development) and NRTI exposure was capable of producing mechanical hyperalgesia at respective dosages that do not independently affect nociception. This affect was attenuated by electron transport train and oxidative stress antagonism (but interestingly, not caspase inhibition), providing additional evidence as to the role mitochondria may play in HIV-SN.98

There is concurrent evidence of inflammatory dysregulation with macrophage infiltration and expression of inflammatory and nociceptive chemokines and cytokines.Specifically, exposure to zalcitabine induced macrophage infiltration and increased chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) and TNF-α expression in the DRG.77,79,80 Similar to viral neurotoxicity, Schwann cells also appear instrumental in the pathogenesis of ARV-related neuropathy. Schwann cell exposure to recombinant gp120 leads to expression of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12), which in turn interacts with CXCR4 and likely causes hyperalgesia through a similar mechanism as seen in in vivo gp120 toxicity.62,79

While significant focus has revolved around the more profoundly neurotoxic NRTIs, there is recent evidence that protease inhibitors may be able to independently elicit neuropathic changes as well as potentiate the neuropathic actions of NRTI therapy. In one observational study, the addition of a protease inhibitor to ARV therapy with stavudine, didanosin, or zalcitabine was associated with a higher incidence of development of both asymptomatic and symptomatic peripheral neuropathy.99 Huang et al.100 demonstrated mechanical hypersensitivity in rats treated with the protease inhibitor indinavir independent of HIV infection. They additionally demonstrated a reduction in intraepidermal nerve fibers on immunostaining of the hind paw after indinavir treatment, thus linking the altered response to mechanical stimuli to a potentially explanatory histological change consistent with findings characteristic of HIV-SN in humans.

Conclusion

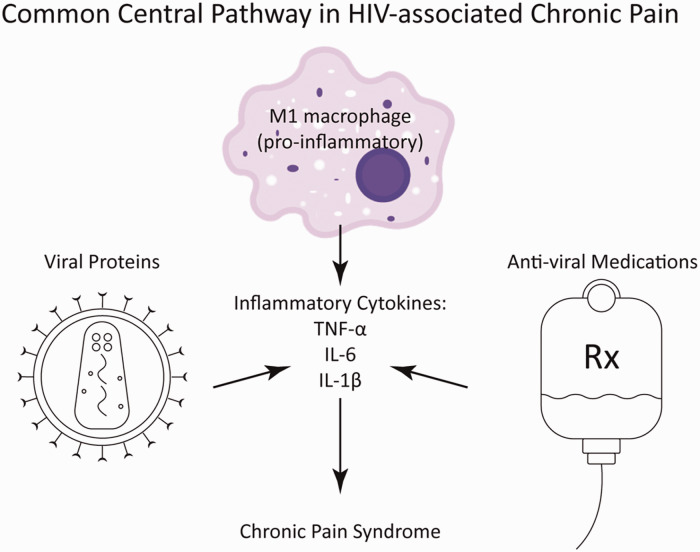

Recent research into the pathogenesis of chronic pain associated with HIV infection indicates that its etiology is multifactorial and involves the host immune response, HIV-1 proteins, and antiretroviral medications (Figure 2). Intriguingly, each of the HIV-1 proteins seems to have a distinct downstream signaling pathway capable of inducing peripheral neuropathic changes and pain. It is also evident that, despite low viral count and nearly normal CD4 levels in PWH on HAART, the circulating or cellular levels of HIV-1 proteins including gp120, Tat, and Vpr remain high. Treatment strategies aimed at targeting a single particular molecule (protein or drug) yield promising results in animal models of peripheral neuropathy. Despite these encouraging findings, translation to the abrogation of chronic pain in humans, where a myriad of instigating factors are simultaneously present and potentially acting synergistically, poses a significant challenge. Moreover, currently, there are no known genetic manipulations or pharmaceutical drugs known to reduce the burden of HIV-1 proteins in humans. It is encouraging, however, that a common convergence becomes apparent in review of the current literature. It is evident from the studies mentioned in this review that most of the HIV-associated chronic pain pathways converge at the release of inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 from peripheral immune cells. The inflammatory cells involved in the development and maintenance of chronic pain contain fewer endogenous opioids compared to their pro-resolution counterparts,51 which may further contribute to increase pain in PWH. Therefore, pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical therapies along with lifestyle modifications aimed at lowering chronic inflammation may have a better chance in succeeding to alleviate chronic pain in PWH.

Figure 2.

HIV-1 proteins, gp120, Tat, and Vpr along with the antiviral drugs increase the release of pro-inflammatory and pro-algetic cytokines, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α from M1 macrophages, which contributes the development of chronic pain in HIV. IL: interleukin; TNF: tumor necrosis factor.

The multifactorial nature of HIV-associated chronic pain warrants a multimodal clinical approach to address a complex process. Direct acknowledgment of the complexity of HIV-associated chronic pain syndrome when communicating with patients may help in setting expectations and discussion options for treatment. We highlight some general clinical considerations related to HIV-associated chronic pain in Table 1 that reflect findings from the literature we have summarized. While research progresses to develop novel therapeutic approaches, physicians should recognize and validate the challenging nature and significance of HIV-associated chronic pain in the day-to-day life of their patients.

Table 1.

Key points to consider in clinical management of HIV-associated chronic pain.

| • HIV infection can lead to chronic pain irrespective of viral load and/or CD4 count |

| • Pain in HIV may be debilitating and contributes to poor quality of life |

| • Pain may develop in the absence of antiviral therapy due to viral proteins and inflammation |

| • NRTIs are associated with development of sensory neuropathy in HIV |

| • Protease inhibitor therapy may lead to sensory neuropathy and may synergize with NRTIs to enhance pain |

| • Alcohol consumption enhances the hyperalgesia associated with NRTI therapy |

| Translational evidence suggests opioid agonism may enhance HIV-induced allodynia and therefore opioids should be avoided |

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; NRTI: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: DRA is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (T32HL129948). JJD is supported by NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K01DK101681 and R03DK119464), and SCIRTS 542907 from the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation. SA is supported by pilot funds from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Center for AIDS Research (P30AI027767-32) and Center for Clinical and Translational Science (UL1TR003096) and by NIH/NHLBI (K12HL143958).

ORCID iD

Saurabh Aggarwal https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7192-1569

References

- 1.Jiao JM, So E, Jebakumar J, George MC, Simpson DM, Robinson-Papp J. Chronic pain disorders in HIV primary care: clinical characteristics and association with healthcare utilization. Pain 2016; 157: 931–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merlin JS, Long D, Becker WC, Cachay ER, Christopoulos KA, Claborn K, Crane HM, Edelman EJ, Harding R, Kertesz SG, Liebschutz JM, Mathews WC, Mugavero MJ, Napravnik S, C. OʼCleirigh C, Saag MS, Starrels JL, Gross R. Brief report: the association of chronic pain and long-term opioid therapy with HIV treatment outcomes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018; 79: 77–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miaskowski C, Penko JM, Guzman D, Mattson JE, Bangsberg DR, Kushel MB. Occurrence and characteristics of chronic pain in a community-based cohort of indigent adults living with HIV infection. J Pain 2011; 12: 1004–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solano JP, Gomes B, Higginson IJ. A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006; 31: 58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merskey H. Pain terms: a list with definitions and notes on usage Recommended by the IASP Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain 1979; 6: 249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yam MF, Loh YC, Tan CS, Khadijah Adam S, Abdul Manan N, Basir R. General pathways of pain sensation and the major neurotransmitters involved in pain regulation. Int J Mol Sci 2018; 19: 2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dydyk AM, Conermann T, Pain, chronic. In StatPearls. Treasure Island: StatPearls, 2020.

- 8.Ellis RJ, Rosario D, Clifford DB, McArthur JC, Simpson D, Alexander T, Gelman BB, Vaida F, Collier A, Marra CM, Ances B, Atkinson JH, Dworkin RH, Morgello S, Grant I, Group CS, CHARTER Study Group. Continued high prevalence and adverse clinical impact of human immunodeficiency virus-associated sensory neuropathy in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: the CHARTER Study. Arch Neurol 2010; 67: 552–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merlin JS, Westfall AO, Chamot E, Overton ET, Willig JH, Ritchie C, Saag MS, Mugavero MJ. Pain is independently associated with impaired physical function in HIV-infected patients. Pain Med 2013; 14: 1985–1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker R, Stein DJ, Jelsma J. Pain in people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. J Int Aids Soc 2014; 17: 18719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsao JC, Stein JA, Dobalian A. Sex differences in pain and misuse of prescription analgesics among persons with HIV. Pain Med 2010; 11: 815–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merlin JS, Westfall AO, Heath SL, Goodin BR, Stewart JC, Sorge RE, Younger J. Brief report: IL-1beta levels are associated with chronic multisite pain in people living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017; 75: e99–e103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson-Papp J, Simpson DM. Neuromuscular diseases associated with HIV-1 infection. Muscle Nerve 2009; 40: 1043–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawson E, Sabin C, Perry N, Richardson D, Gilleece Y, Churchill D, Dean G, Williams D, Fisher M, Walker-Bone K. Is HIV painful? An epidemiologic study of the prevalence and risk factors for pain in HIV-infected patients. Clin J Pain 2015; 31: 813–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nair SN, Mary TR, Prarthana S, Harrison P. Prevalence of pain in patients with HIV/AIDS: A cross-sectional survey in a South Indian State. Indian J Palliat Care 2009; 15: 67–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalakas MC. Peripheral neuropathy and antiretroviral drugs. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2001; 6: 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mawuntu AHP, Mahama CN, Khosama H, Estiasari R, Imran D. Early detection of peripheral neuropathy using stimulated skin wrinkling test in human immunodeficiency virus infected patients: A cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018; 97: e11526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koeppe J, Armon C, Lyda K, Nielsen C, Johnson S. Ongoing pain despite aggressive opioid pain management among persons with HIV. Clin J Pain 2010; 26: 190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Semenkovich K, Chockalingam R, Scherrer JF, Panagopoulos VN, Lustman PJ, Ray JM, Freedland KE, Svrakic DM. Prescription opioid analgesics increase risk of major depression: new evidence, plausible neurobiological mechanisms and management to achieve depression prophylaxis. Mo Med 2014; 111: 148–154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP. The changing face of heroin use in the United States: a retrospective analysis of the past 50 years. JAMA Psychiatry 2014; 71: 821–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knowlton AR, Nguyen TQ, Robinson AC, Harrell PT, Mitchell MM. Pain symptoms associated with opioid use among vulnerable persons with HIV: an exploratory study with implications for palliative care and opioid abuse prevention. J Palliat Care 2015; 31: 228–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsao JC, Dobalian A, Stein JA. Illness burden mediates the relationship between pain and illicit drug use in persons living with HIV. Pain 2005; 119: 124–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsao JC, Stein JA, Dobalian A. Pain, problem drug use history, and aberrant analgesic use behaviors in persons living with HIV. Pain 2007; 133: 128–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes JR, Bickel WK, Higgins ST. Buprenorphine for pain relief in a patient with drug abuse. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1991; 17: 451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Umbricht A, Hoover DR, Tucker MJ, Leslie JM, Chaisson RE, Preston KL. Opioid detoxification with buprenorphine, clonidine, or methadone in hospitalized heroin-dependent patients with HIV infection. Drug Alcohol Depend 2003; 69: 263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu B, Liu X, Tang SJ. Interactions of opioids and HIV infection in the pathogenesis of chronic pain. Front Microbiol 2016; 7: 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zule WA, Oramasionwu C, Evon D, Hino S, Doherty IA, Bobashev GV, Wechsberg WM. Event-level analyses of sex-risk and injection-risk behaviors among nonmedical prescription opioid users. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2016; 42: 689–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiguchi N, Kobayashi D, Saika F, Matsuzaki S, Kishioka S. Pharmacological regulation of neuropathic pain driven by inflammatory macrophages. Int J Mol Sci 2017; 18: 2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calvo M, Dawes JM, Bennett DL. The role of the immune system in the generation of neuropathic pain. Lancet Neurol 2012; 11: 629–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cairns BE, Arendt-Nielsen L, Sacerdote P. Perspectives in pain research 2014: neuroinflammation and glial cell activation: the cause of transition from acute to chronic pain? Scand J Pain 2015; 6: 3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burdo TH, Orzechowski K, Knight HL, Miller AD, Williams K. Dorsal root ganglia damage in SIV-infected rhesus macaques: an animal model of HIV-induced sensory neuropathy. Am J Pathol 2012; 180: 1362–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hahn K, Robinson B, Anderson C, Li W, Pardo CA, Morgello S, Simpson D, Nath A. Differential effects of HIV infected macrophages on dorsal root ganglia neurons and axons. Exp Neurol 2008; 210: 30–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laast VA, Shim B, Johanek LM, Dorsey JL, Hauer PE, Tarwater PM, Adams RJ, Pardo CA, McArthur JC, Ringkamp M, Mankowski JL. Macrophage-mediated dorsal root ganglion damage precedes altered nerve conduction in SIV-infected macaques. Am J Pathol 2011; 179: 2337–2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pardo CA, McArthur JC, Griffin JW. HIV neuropathy: insights in the pathology of HIV peripheral nerve disease. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2001; 6: 21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lakritz JR, Robinson JA, Polydefkis MJ, Miller AD, Burdo TH. Loss of intraepidermal nerve fiber density during SIV peripheral neuropathy is mediated by monocyte activation and elevated monocyte chemotactic proteins. J Neuroinflammation 2015; 12: 237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang F, Zhang S, Jeon R, Vuckovic I, Jiang X, Lerman A, Folmes CD, Dzeja PD, Herrmann J. Interferon gamma induces reversible metabolic reprogramming of M1 macrophages to sustain cell viability and pro-inflammatory activity. EBioMedicine 2018; 30: 303–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van der Watt JJ, Wilkinson KA, Wilkinson RJ, Heckmann JM. Plasma cytokine profiles in HIV-1 infected patients developing neuropathic symptoms shortly after commencing antiretroviral therapy: a case-control study. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14: 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng W, Huang W, Liu S, Levitt RC, Candiotti KA, Lubarsky DA, Hao S. Interleukin 10 mediated by herpes simplex virus vectors suppresses neuropathic pain induced by human immunodeficiency virus gp120 in rats. Anesth Analg 2014; 119: 693–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chauhan P, Sheng WS, Hu S, Prasad S, Lokensgard JR. Nitrosative damage during retrovirus infection-induced neuropathic pain. J Neuroinflammation 2018; 15: 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu T, van Rooijen N, Tracey DJ. Depletion of macrophages reduces axonal degeneration and hyperalgesia following nerve injury. Pain 2000; 86: 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thacker MA, Clark AK, Marchand F, McMahon SB. Pathophysiology of peripheral neuropathic pain: immune cells and molecules. Anesth Analg 2007; 105: 838–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ossipov MH, Morimura K, Porreca F. Descending pain modulation and chronification of pain. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2014; 8: 143–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stein C. New concepts in opioid analgesia. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2018; 27: 765–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mousa SA, Shakibaei M, Sitte N, Schafer M, Stein C. Subcellular pathways of beta-endorphin synthesis, processing, and release from immunocytes in inflammatory pain. Endocrinology 2004; 145: 1331–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Przewłocki R, Hassan AH, Lason W, Epplen C, Herz A, Stein C. Gene expression and localization of opioid peptides in immune cells of inflamed tissue: functional role in antinociception. Neuroscience 1992; 48: 491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharp B, Linner K. What do we know about the expression of proopiomelanocortin transcripts and related peptides in lymphoid tissue? Endocrinology 1993; 133: 1921A–1921B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sibinga NE, Goldstein A. Opioid peptides and opioid receptors in cells of the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol 1988; 6: 219–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cabot PJ, Carter L, Gaiddon C, Zhang Q, Schafer M, Loeffler JP, Stein C. Immune cell-derived beta-endorphin. Production, release, and control of inflammatory pain in rats. J Clin Invest 1997; 100: 142–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cabot PJ, Carter L, Schafer M, Stein C. Methionine-enkephalin-and dynorphin A-release from immune cells and control of inflammatory pain. Pain 2001; 93: 207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Machelska H, Cabot PJ, Mousa SA, Zhang Q, Stein C. Pain control in inflammation governed by selectins. Nat Med 1998; 4: 1425–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pannell M, Labuz D, Celik MO, Keye J, Batra A, Siegmund B, Machelska H. Adoptive transfer of M2 macrophages reduces neuropathic pain via opioid peptides. J Neuroinflammation 2016; 13: 262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bouhlel MA, Derudas B, Rigamonti E, Dievart R, Brozek J, Haulon S, Zawadzki C, Jude B, Torpier G, Marx N, Staels B, Chinetti-Gbaguidi G. PPARgamma activation primes human monocytes into alternative M2 macrophages with anti-inflammatory properties. Cell Metab 2007; 6: 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J Clin Invest 2012; 122: 787–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hasegawa-Moriyama M, Ohnou T, Godai K, Kurimoto T, Nakama M, Kanmura Y. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist rosiglitazone attenuates postincisional pain by regulating macrophage polarization. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2012; 426: 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kiguchi N, Kobayashi Y, Saika F, Sakaguchi H, Maeda T, Kishioka S. Peripheral interleukin-4 ameliorates inflammatory macrophage-dependent neuropathic pain. Pain 2015; 156: 684–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lakritz JR, Bodair A, Shah N, O’Donnell R, Polydefkis MJ, Miller AD, Burdo TH. Monocyte traffic, dorsal root ganglion histopathology, and loss of intraepidermal nerve fiber density in SIV peripheral neuropathy. Am J Pathol 2015; 185: 1912–1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alfano M, Graziano F, Genovese L, Poli G. Macrophage polarization at the crossroad between HIV-1 infection and cancer development. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013; 33: 1145–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oh SB, Tran PB, Gillard SE, Hurley RW, Hammond DL, Miller RJ. Chemokines and glycoprotein120 produce pain hypersensitivity by directly exciting primary nociceptive neurons. J Neurosci 2001; 21: 5027–5035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaul M, Lipton SA. Chemokines and activated macrophages in HIV gp120-induced neuronal apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999; 96: 8212–8216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu QH, Williams DA, McManus C, Baribaud F, Doms RW, Schols D, De Clercq E, Kotlikoff MI, Collman RG, Freedman BD. HIV-1 gp120 and chemokines activate ion channels in primary macrophages through CCR5 and CXCR4 stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97: 4832–4837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moss PJ, Huang W, Dawes J, Okuse K, McMahon SB, Rice AS. Macrophage-sensory neuronal interaction in HIV-1 gp120-induced neurotoxicitydouble dagger. Br J Anaesth 2015; 114: 499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Keswani SC, Polley M, Pardo CA, Griffin JW, McArthur JC, Hoke A. Schwann cell chemokine receptors mediate HIV-1 gp120 toxicity to sensory neurons. Ann Neurol 2003; 54: 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zheng W, Ouyang H, Zheng X, Liu S, Mata M, Fink DJ, Hao S. Glial TNFalpha in the spinal cord regulates neuropathic pain induced by HIV gp120 application in rats. Mol Pain 2011; 7: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yi H, Liu S, Kashiwagi Y, Ikegami D, Huang W, Kanda H, Iida T, Liu CH, Takahashi K, Lubarsky DA, Hao S. Phosphorylated CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta contributes to rat HIV-related neuropathic pain: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Neurosci 2018; 38: 555–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li Z, Mao Y, Liang L, Wu S, Yuan J, Mo K, Cai W, Mao Q, Cao J, Bekker A, Zhang W, Tao YX. The transcription factor C/EBPbeta in the dorsal root ganglion contributes to peripheral nerve trauma-induced nociceptive hypersensitivity. Sci Signal 2017; 10: eaam5345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shi Y, Gelman BB, Lisinicchia JG, ,Tang SJ. Chronic-pain-associated astrocytic reaction in the spinal cord dorsal horn of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J Neurosci 2012; 32: 10833–10840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kanda H, Liu S, Iida T, Yi H, Huang W, Levitt RC, Lubarsky DA, Candiotti KA, Hao S. Inhibition of mitochondrial fission protein reduced mechanical allodynia and suppressed spinal mitochondrial superoxide induced by perineural human immunodeficiency virus gp120 in rats. Anesth Analg 2016; 122: 264–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Avdoshina V, Fields JA, Castellano P, Dedoni S, Palchik G, Trejo M, Adame A, Rockenstein E, Eugenin E, Masliah E, Mocchetti I. The HIV protein gp120 alters mitochondrial dynamics in neurons. Neurotox Res 2016; 29: 583–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burnstock G. Purinergic mechanisms and pain—an update. Eur J Pharmacol 2013; 716: 24–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chizh BA, Illes P. P2X receptors and nociception. Pharmacol Rev 2001; 53: 553–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Katagiri A, Shinoda M, Honda K, Toyofuku A, Sessle BJ, Iwata K. Satellite glial cell P2Y12 receptor in the trigeminal ganglion is involved in lingual neuropathic pain mechanisms in rats. Mol Pain 2012; 8: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kobayashi K, Yamanaka H, Noguchi K. Expression of ATP receptors in the rat dorsal root ganglion and spinal cord. Anat Sci Int 2013; 88: 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yi Z, Xie L, Zhou C, Yuan H, Ouyang S, Fang Z, Zhao S, Jia T, Zou L, Wang S, Xue Y, Wu B, Gao Y, Li G, Liu S, Xu H, Xu C, Zhang C, Liang S. P2Y12 receptor upregulation in satellite glial cells is involved in neuropathic pain induced by HIV glycoprotein 120 and 2′,3′-dideoxycytidine. Purinergic Signal 2018; 14: 47–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yi Z, Rao S, Ouyang S, Bai Y, Yang J, Ma Y, Han X, Wu B, Zou L, Jia T, Zhao S, Hu X, Lei Q, Gao Y, Liu S, Xu H, Zhang C, Liang S, Li G. A317491 relieved HIV gp120-associated neuropathic pain involved in P2X3 receptor in dorsal root ganglia. Brain Res Bull 2017; 130: 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhao S, Yang J, Han X, Gong Y, Rao S, Wu B, Yi Z, Zou L, Jia T, Li L, Yuan H, Shi L, Zhang C, Gao Y, Li G, Liu S, Xu H, Liu H, Liang S. Effects of nanoparticle-encapsulated curcumin on HIV-gp120-associated neuropathic pain induced by the P2X3 receptor in dorsal root ganglia. Brain Res Bull 2017; 135: 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wu B, Peng L, Xie J, Zou L, Zhu Q, Jiang H, Yi Z, Wang S, Xue Y, Gao Y, Li G, Liu S, Zhang C, Li G, Liang S, Xiong H. The P2X7 receptor in dorsal root ganglia is involved in HIV gp120-associated neuropathic pain. Brain Res Bull 2017; 135: 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wallace VC, Blackbeard J, Segerdahl AR, Hasnie F, Pheby T, McMahon SB, Rice AS. Characterization of rodent models of HIV-gp120 and anti-retroviral-associated neuropathic pain. Brain 2007; 130: 2688–2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Takahashi K, Yi H, Liu CH, Liu S, Kashiwagi Y, Patin DJ, Hao S. Spinal bromodomain-containing protein 4 contributes to neuropathic pain induced by HIV glycoprotein 120 with morphine in rats. Neuroreport 2018; 29: 441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kamerman PR, Moss PJ, Weber J, Wallace VC, Rice AS, Huang W. Pathogenesis of HIV-associated sensory neuropathy: evidence from in vivo and in vitro experimental models. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2012; 17: 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wallace VC, Blackbeard J, Pheby T, Segerdahl AR, Davies M, Hasnie F, Hall S, McMahon SB, Rice AS. Pharmacological, behavioural and mechanistic analysis of HIV-1 gp120 induced painful neuropathy. Pain 2007; 133: 47–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Carvallo L, Lopez L, Fajardo JE, Jaureguiberry-Bravo M, Fiser A, Berman JW. HIV-Tat regulates macrophage gene expression in the context of neuroAIDS. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0179882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rozzi SJ, Avdoshina V, Fields JA, Trejo M, Ton HT, Ahern GP, Mocchetti I. Human immunodeficiency virus promotes mitochondrial toxicity. Neurotox Res 2017; 32: 723–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rozzi SJ, Borelli G, Ryan K, Steiner JP, Reglodi D, Mocchetti I, Avdoshina V. PACAP27 is protective against tat-induced neurotoxicity. J Mol Neurosci 2014; 54: 485–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Eugenin EA, King JE, Nath A, Calderon TM, Zukin RS, Bennett MV, Berman JW. HIV-tat induces formation of an LRP-PSD-95-NMDAR-nNOS complex that promotes apoptosis in neurons and astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 3438–3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim HJ, Martemyanov KA, Thayer SA. Human immunodeficiency virus protein Tat induces synapse loss via a reversible process that is distinct from cell death. J Neurosci 2008; 28: 12604–12613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Krogh KA, Wydeven N, Wickman K, Thayer SA. HIV-1 protein Tat produces biphasic changes in NMDA-evoked increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentration via activation of Src kinase and nitric oxide signaling pathways. J Neurochem 2014; 130: 642–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Haughey NJ, Nath A, Mattson MP, Slevin JT, Geiger JD. HIV-1 Tat through phosphorylation of NMDA receptors potentiates glutamate excitotoxicity. J Neurochem 2001; 78: 457–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chivero ET, Guo ML, Periyasamy P, Liao K, Callen SE, Buch S. HIV-1 Tat primes and activates microglial NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuroinflammation. J Neurosci 2017; 37: 3599–3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fiume G, Vecchio E, De Laurentiis A, Trimboli F, Palmieri C, Pisano A, Falcone C, Pontoriero M, Rossi A, Scialdone A, Fasanella Masci F, Scala G, Quinto I. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 Tat activates NF-kappaB via physical interaction with IkappaB-alpha and p65. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40: 3548–3562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wodarski R, Bagdas D, Paris JJ, Pheby T, Toma W, Xu R, Damaj MI, Knapp PE, Rice ASC, Hauser KF. Reduced intraepidermal nerve fibre density, glial activation, and sensory changes in HIV type-1 Tat-expressing female mice: involvement of Tat during early stages of HIV-associated painful sensory neuropathy. Pain Rep 2018; 3: e654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chi X, Amet T, Byrd D, Chang KH, Shah K, Hu N, Grantham A, Hu S, Duan J, Tao F, Nicol G, Yu Q. Direct effects of HIV-1 Tat on excitability and survival of primary dorsal root ganglion neurons: possible contribution to HIV-1-associated pain. PLoS One 2011; 6: e24412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fitting S, Scoggins KL, Xu R, Dever SM, Knapp PE, Dewey WL, Hauser KF. Morphine efficacy is altered in conditional HIV-1 Tat transgenic mice. Eur J Pharmacol 2012; 689: 96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fitting S, Stevens DL, Khan FA, Scoggins KL, Enga RM, Beardsley PM, Knapp PE, Dewey WL, Hauser KF. Morphine tolerance and physical dependence are altered in conditional HIV-1 Tat transgenic mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2016; 356: 96–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gonzalez ME. The HIV-1 Vpr protein: a multifaceted target for therapeutic intervention. Int J Mol Sci 2017; 18: 126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ferrucci A, Nonnemacher MR, Wigdahl B. Extracellular HIV-1 viral protein R affects astrocytic glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase activity and neuronal survival. J Neurovirol 2013; 19: 239–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Acharjee S, Noorbakhsh F, Stemkowski PL, Olechowski C, Cohen EA, Ballanyi K, Kerr B, Pardo C, Smith PA, Power C. HIV-1 viral protein R causes peripheral nervous system injury associated with in vivo neuropathic pain. FASEB J 2010; 24: 4343–4353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Phillips TJ, Cherry CL, Cox S, Marshall SJ, Rice AS. Pharmacological treatment of painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS One 2010; 5: e14433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ferrari LF, Levine JD. Alcohol consumption enhances antiretroviral painful peripheral neuropathy by mitochondrial mechanisms. Eur J Neurosci 2010; 32: 811–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Evans SR, Ellis RJ, Chen H, Yeh TM, Lee AJ, Schifitto G, Wu K, Bosch RJ, McArthur JC, Simpson DM, Clifford DB. Peripheral neuropathy in HIV: prevalence and risk factors. AIDS 2011; 25: 919–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Huang W, Calvo M, Pheby T, Bennett DL, Rice AS. A rodent model of HIV protease inhibitor indinavir induced peripheral neuropathy. Pain 2017; 158: 75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]