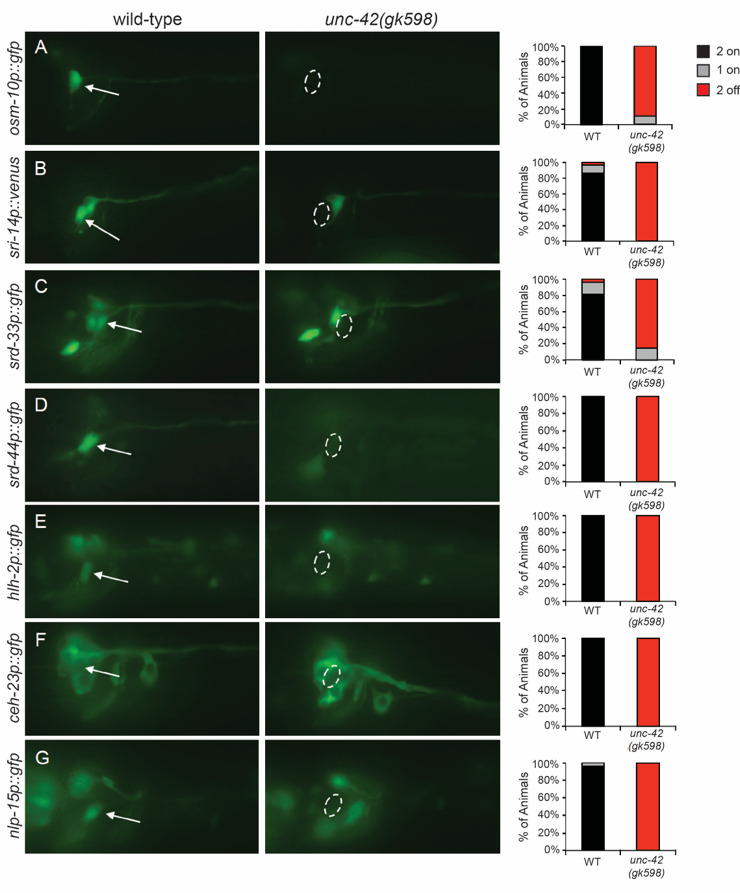

Figure 1. unc-42 regulates terminal gene battery expression in the ASH nociceptors.

unc-42 function is required for the expression of ASH terminal differentiation gene marker expression specifically in the ASH neuron pair; expression in other neurons did not appear to be affected. The ASH neurons were identified by positional labeling with the lipophilic dye DiD, as previously described (Perkins et al. 1986). (A-G) Images of GFP reporter expression were obtained with a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 Microscope, high resolution AxioCam MRm digital camera and Zeiss AxioVision software. Left panels indicate ASH neurons in wild-type animals, indicated by arrows. Right panels show the lack of expression in the ASH neurons of unc-42(gk598) mutant animals, indicated by dashed circles. Bar graphs show the percentage of animals examined showing GFP marker expression in 2, 1 or neither of the ASH neurons. A mixed age population of n > 40 animals was examined for each transgene.

Description

The genes encoding transcription factors that initiate the terminal differentiation programs within individual neurons have been termed “terminal selectors” (Hobert 2008). They are considered master regulators of neuronal identity because they integrate upstream lineage inputs to ultimately drive (directly and/or indirectly) the expression of all terminal differentiation features of a neuron (Hobert 2008; Bertrand and Hobert 2010). The paired-like homeodomain transcription factor UNC-42 has been proposed to function as the terminal selector in the developmental specification of the ASH polymodal nociceptors in C. elegans (Baran et al. 1999). Consistent with the role of a terminal selector, unc-42(e419) loss-of-function mutants were shown to lack the expression of the putative chemoreceptor genes sra-6 and srb-6 specifically in the ASHs, while, for example, srb-6 expression in the ADL and ADF sensory neurons was unaffected (Baran et al. 1999). unc-42(e419) mutants also lack ASH expression of several other terminal identity markers: three Gα encoding genes (gpa-11, gpa-13 and gpa-15), the neuropeptide encoded by flp-21, and the eat-4 vesicular glutamate transporter (Serrano-Saiz et al. 2013). Furthermore, loss of UNC-42 function disrupted behavioral responses to high osmolarity and nose touch (Baran et al. 1999), which are both detected primarily by the ASHs (Bargmann et al. 1990; Kaplan and Horvitz 1993). However, the severity of the nose touch defect was likely due to developmental defects in both the ASH sensory neurons as well as some downstream interneurons, where altered glutamate receptor expression accompanies loss of UNC-42 (Baran et al. 1999; Brockie et al. 2001).

| Identity marker | Expression affected in unc-42(gk598) mutant background | ||

| ASH nociceptive neuron | High osmolarity detection | osm-10 |

YES |

| GPCR |

sra-6 sri-14 srd-33 srd-44 srd-10 srz-1 |

YES* YES YES YES YES (partial) NO |

|

| Transcription factor |

hlh-2 ceh-23 nhr-79 |

YES YES NO |

|

| Neuropeptide |

nlp-15 nlp-3 |

YES NO |

|

| TRP channel |

osm-9 ocr-2 |

NO NO |

|

| Axon guidance |

unc-40 sax-3 |

NO NO |

|

Table 1: Summary of the effect of unc-42(gk598) on ASH terminal marker gene expression *sra-6 expression in ASH was previously reported to be affected by unc-42(e419) (Baran et al. 1999).

Using the unc-42(gk598) allele, we confirmed the role of UNC-42 in regulating ASH terminal markers, and identified seven additional genes whose ASH expression strongly depends upon UNC-42 (Figure 1 and Table 1). These genes encode OSM-10, additional predicted GPCRs, transcription factors and a neuropeptide. However, UNC-42 is unlikely to function as the sole terminal selector in ASH. For example, srd-10 expression is only partially affected in the unc-42(gk598) mutants, with only ~20% of animals losing expression in one ASH (image not shown). In addition, ASH expression of some genes (srz-1, nhr-79, nlp-3, osm-9, ocr-2, unc-40 and sax-3) was found to be unaffected in unc-42(gk598) animals (Table 1). We note that several of these are either expressed broadly throughout the nervous system, or function in several sensory neurons. As such, they may not necessarily be constituents of the terminally differentiated gene battery of the ASHs. Combined, UNC-42 broadly regulates the expression of ASH identity markers, although additional transcription factors are likely to also contribute.

Reagents

DiD was purchased from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen).

The VC1444 unc-42(gk598) strain was generated by the C. elegans Reverse Genetics Core Facility at the University of British Columbia, which is part of the International C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium. The gk598 allele contains a 1430 basepair deletion (898 basepairs of 5’ UTR sequence, exon 1 and 481 basepairs of intron 1). VC1444 was outcrossed 6x to N2 to generate FG498 for use in this study. Some of the strains used in this study were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded in part by the National Institutes of Health – National Center for Research Resources.

Strains used in this study include: N2 Bristol wild-type, FG498 unc-42(gk598), CX3465 kyIs39 [sra-6::gfp + lin-15(+)], HA1695 rtIs27 [osm-10p::gfp], PY5163 [oyEx srd-44p::gfp, coelRFP] line 1, NK885 unc-119(ed4);qyIs174 [hlh-2p::gfp::hlh-2 + unc-119(+)], CX2565 kyIs4 lin-15A(n765) [ceh-23p::unc-76::gfp + lin-15(+)], RW10748 unc-119(ed3); zuIs178; stIs10024; stIs10549 [stIs10549 = nhr-79::H1-wCherry + unc-119(+)], HA357 rtEx251 [nlp-15p::gfp + lin-15(+)]; lin-15B lin-15A(n765), AL132 icIs132 [unc-40::gfp], HA341 lin-15; rtEx235 [nlp-3::gfp], LX990 lin-15B lin-15A(n765); vsEx494 [ocr-2p::gfp::ocr-2 3’utr + lin-15(+)], CX3716lin-15B lin-15A(n765) kyIs141 [osm-9::gfp5 + lin-15(+)], IC692 quEx162 [sax-3p::gfp + (pRF4) rol-6]. Transgenes were examined in the wild-type andunc-42(gk598) background. For the generation of extrachromosomal arrays, germline transformations were performed as previously described (Mello et al. 1991). Plasmids injected for analysis include: sri-14p::venus, pFG258 srd-33p::gfp and pFG233 srd-10p::gfp. Transgenic lines were examined in the N2 wild-type background, and at least one array was chosen to be crossed into the unc-42(gk598) background for comparison. Strains generated in our lab for this study have not been sent to the CGC.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Anne Hart, Takaaki Hirotsu and Piali Sengupta for reagents and Oliver Hobert for valuable discussions.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant 1351649 to DMF).

References

- Baran R, Aronoff R, Garriga G. The C. elegans homeodomain gene unc-42 regulates chemosensory and glutamate receptor expression. Development. 1999 May 01;126(10):2241–2251. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.10.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann CI, Thomas JH, Horvitz HR. Chemosensory cell function in the behavior and development of Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1990;55:529–538. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1990.055.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand V, Hobert O. Lineage programming: navigating through transient regulatory states via binary decisions. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010 May 27;20(4):362–368. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockie PJ, Madsen DM, Zheng Y, Mellem J, Maricq AV. Differential expression of glutamate receptor subunits in the nervous system of Caenorhabditis elegans and their regulation by the homeodomain protein UNC-42. J Neurosci. 2001 Mar 01;21(5):1510–1522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01510.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert O. Regulatory logic of neuronal diversity: terminal selector genes and selector motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Dec 22;105(51):20067–20071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806070105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JM, Horvitz HR. A dual mechanosensory and chemosensory neuron in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Mar 15;90(6):2227–2231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello CC, Kramer JM, Stinchcomb D, Ambros V. Efficient gene transfer in C.elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 1991 Dec 01;10(12):3959–3970. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins LA, Hedgecock EM, Thomson JN, Culotti JG. Mutant sensory cilia in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1986 Oct 01;117(2):456–487. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90314-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Saiz E, Poole RJ, Felton T, Zhang F, De La Cruz ED, Hobert O. Modular control of glutamatergic neuronal identity in C. elegans by distinct homeodomain proteins. Cell. 2013 Oct 24;155(3):659–673. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]