Abstract

Chemogenetics enables non-invasive chemical control over cell populations in behaving animals. However, existing small molecule agonists show insufficient potency or selectivity. There is also need for chemogenetic systems compatible with both research and human therapeutic applications. We developed a new ion channel-based platform for cell activation and silencing that is controlled by low doses of the anti-smoking drug varenicline. We then synthesized novel sub-nanomolar potency agonists, called uPSEMs, with high selectivity for the chemogenetic receptors. uPSEMs and their receptors were characterized in brains of mice and a rhesus monkey by in vivo electrophysiology, calcium imaging, positron emission tomography, behavioral efficacy testing, and receptor counterscreening. This platform of receptors and selective ultrapotent agonists enables potential research and clinical applications of chemogenetics.

One sentence summary:

Engineered receptors and ultrapotent agonists enable selective control of cells in vivo for research and potential therapies.

Introduction

Chemogenetics (1) targets an exogenous receptor to a specific cell population to control cellular activity only when engaged by a selective agonist. The approach is generalizable because the same receptor and agonist combination is used for different cell types. Chemogenetic tools have widespread utility in animal models (2) and for therapeutic applications (3, 4). However, there are fundamental shortcomings of the small molecule agonists for research purposes (5–7). Moreover, human therapies would be facilitated by chemogenetic receptors that are potently activated by existing clinically approved drugs.

Chemogenetic systems (Table S1) based on engineered GPCRs, called DREADDs, have been used with the agonist clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) (8, 9), but CNO is a substrate for the P-glycoprotein efflux pump (PgP) and is metabolically converted to clozapine, which is the active agent in the brain (5, 6, 10). Clozapine binds with high affinity to many receptors and has side effects such as behavioral inhibition (7) and potentially fatal agranulocytosis (11). Chemogenetic GPCR tools often rely on GPCR over-expression (12) to achieve high potency responses, and effects on cell electrical activity are variable due to indirect coupling to ion channels. Engineered ligand gated ion channels (LGICs) enable direct control over cellular activity by a small molecule. However, despite decades of development, chemogenetic tools have been hindered by limitations of the small molecule agonists.

Pharmacologically Selective Actuator Modules (PSAMs) are a modular chemogenetic platform based on modified α7 nAChR ligand binding domains (LBDs) that are engineered to selectively interact with brain-penetrating synthetic agonists called Pharmacologically Selective Effector Molecules (PSEMs). PSAMs can be combined with various ion pore domains (IPDs) from different ion channels to produce chimeric LGICs with common pharmacology but distinct functional properties (Fig. 1A). PSAM-5HT3 chimeric channels are cation-selective and PSAM-GlyR channels are chloride-selective, leading to neuron activation or silencing, respectively, in response to PSEM agonists (Fig. 1A) (13). Engineered chimeric channels have been used to investigate the involvement of specific neuron populations in multiple functions (2). The primary limitations of PSEMs are short clearance times (30–60 min) and low micromolar potency (13), which are not ideal for in vivo applications. In addition, the sensitivity of PSAMs to clinically approved drugs is unknown. We combined structure-guided ion channel engineering with synthetic chemistry and testing by in vivo imaging, electrophysiology, and behavioral perturbation to develop an ultrapotent chemogenetic system for research and potential clinical applications.

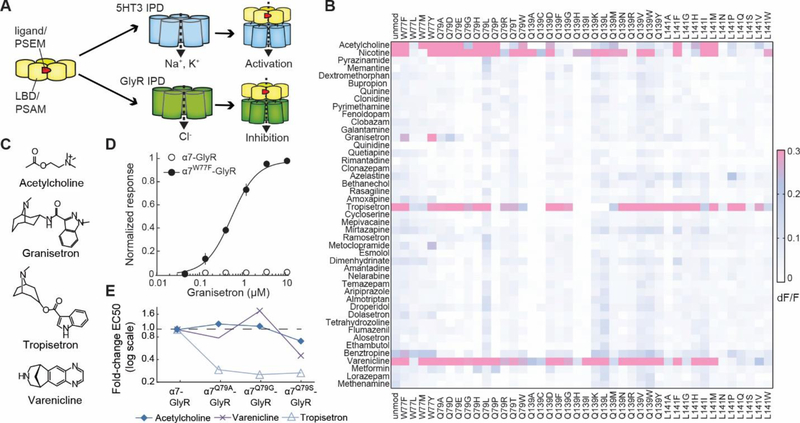

Figure 1.

Screen of mutant α7 nAChR LBD ion channel activity against clinically used drugs. A) Schematic of modular PSAM-IPD chimeric channels for cell activation and inhibition. B) Screen of 41 α7–5HT3 channels with mutant LBDs against 44 clinically used drugs. C) Key molecules. D) Granisetron sensitivity conferred by Trp77→Phe. E) Tropisetron potency improved by Gln79 mutations.

Results

Engineering channel sensitivity to clinically used drugs

We examined 44 clinically used drugs with chemical similarity to nicotinic receptor agonists in a membrane potential (MP) screen against a panel of 41 chimeric channels with mutant α7 nAChR LBDs spliced onto the 5HT3 IPD (α7–5HT3) (13) (Fig. 1B). The MP assay yields dose responses that reflect sustained channel activation, which is most relevant for chemogenetic applications (Fig. S1) (13).

The anti-emetic drug, granisetron (Fig.1C), which has no agonist activity at α7 nAChR, activated α7W77F-5HT3 (EC50MP: 1.2 μM) and α7W77Y-5HT3 (EC50MP: 1.1 μM) (Fig. 1D) as well as the α7W77F-GlyR chloride-selective chimeric channel (EC50MP: 0.60 ± 0.07 μM; mean ± SEM) (Fig. 1D). Thus, Trp77 in the LBD controls off-target selectivity of granisetron at α7 nAChR.

Another anti-emetic drug, tropisetron, and the anti-smoking drug, varenicline, activated many of the mutant channels (Fig. 1B-C, S2A,B), consistent with the established α7 nAChR agonist activity of these molecules (14, 15). Mutation at Gln79→Gly enhanced the activity of tropisetron 4-fold (EC50MP: 38 ± 3 nM) (Fig. 1E) as well as the potency of additional α7 nAChR agonists (Fig. S2). Varenicline agonist activity was slightly improved relative to α7–5HT3 with mutations at Gln79→Ser (EC50MP: 470 ± 70 nM) or Gln139→Leu (EC50MP: 300 nM) (Fig. S2B).

Ultrapotent chemogenetic receptor for varenicline

Varenicline is an especially attractive molecule for chemogenetic applications in the central nervous system because 1) it is well-tolerated by patients at low doses (16, 17), 2) it has excellent brain penetrance (18), 3) it is not a PgP substrate (19), 4) it has low binding to plasma proteins, as well as 5) long-lived pharmacology in monkeys and humans (t1/2 >17 h) and acceptable half-life in mice and rats (t1/2: 1.4 h and 4 h, respectively) (20). Anti-smoking activity is reportedly due to α4β2 nAChR partial agonism, but varenicline has off-target agonist activity at 5HT3-R (21) and at α7 nAChR (15), and it is the latter activity that we exploited for chemogenetic applications. Comparison of crystal structures of acetylcholine binding proteins complexed with varenicline or tropisetron showed distinct binding poses of the two molecules (Fig. 2A) (22, 23). The tropisetron indole substituent is positioned at the binding pocket entrance, near Gln79, consistent with the potency enhancing effect of mutating Gln79 to smaller amino acid residues for tropisetron and other tropane and quinuclidine α7 nAChR agonists (Fig. S2C,D). In contrast, varenicline binds in an orientation that directs its quinoxaline ring system towards the interior of the LBD, near Val106, which is equivalent to amino acid Leu131 in the α7 nAChR LBD (Fig. 2A), and this binding pose may explain the limited potency enhancement of varenicline observed for our initial panel of 41 mutant channels (Fig. S2B). This amino acid residue had not been investigated previously, so we examined the influence of mutations at Leu131 on agonist potency.

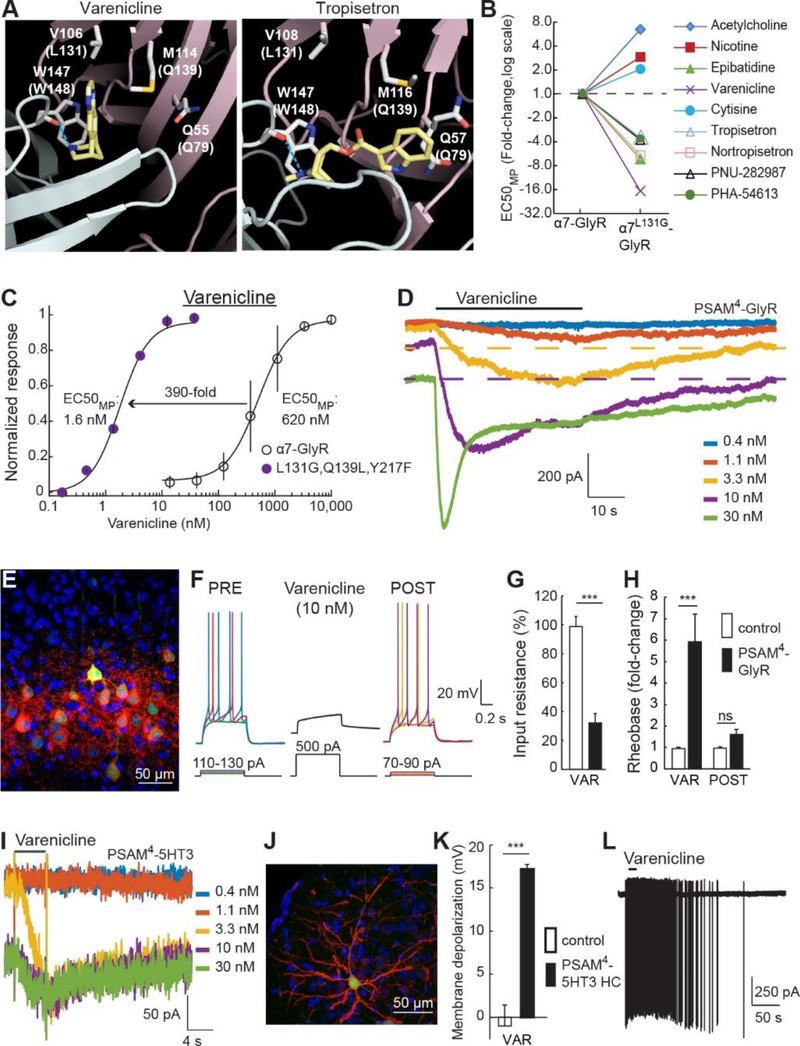

Figure 2.

Development of an ultrapotent PSAM for varenicline. A) Varenicline (left) and tropisetron (right) bind AChBPs in distinct orientations. Dashed line: H-bond with Trp147. Parentheses: homologous α7 nAChR pre-protein numbering. B) Leu131→Gly oppositely affects potency for varenicline, ACh, and other α7 nAChR agonists. C) Potency enhancement of varenicline for α7L131G,Q139L,Y217F-GlyR. D) Varenicline whole cell voltage clamp response at α7L131G,Q139L,Y217F-GlyR. Baseline shifts reflect slow washout (dashed lines). E) Cortical layer 2/3 neurons expressing EGFP and PSAM4-GlyR with non-permeabilized cell-surface labeling by α-Bungarotoxin-Alexa594 (αBgt-594). F-H) Action potential firing strongly suppressed by varenicline strongly in neurons expressing PSAM4-GlyR (F) due to reduced input resistance (G) and elevated rheobase (H). I) Varenicline binding to PSAM4-5HT3 elicits a weakly desensitizing current with high potency. Baseline shifts reflect slow washout. J) αBgt-594 labeling of PSAM4-5HT3 HC (red) on cell surface of a cortical layer 2/3 neuron co-expressing EGFP. K,L) Varenicline (15 nM) depolarizes (K) and elicits action potentials (L) in neurons expressing PSAM4-5HT3 HC. Error bars are SEM. Mann Whitney U-test, n.s. P>0.05, ***P<0.001.

Replacement of Leu131 with smaller amino acid residues markedly increased the potency of varenicline, tropisetron, and several other synthetic agonists while reducing the potency of canonical agonists, ACh and nicotine (Fig. 2B, S3A). α7L131G-GlyR showed 17-fold potency enhancement for varenicline (EC50MP: 37 ± 26 nM), but only 3-fold improvement for tropisetron (Fig. 2B), which is consistent with their orthogonal binding orientations (Fig. 2A). Based on secondary screening results (Fig. S2B), we combined additional mutations with Leu131→Gly to further improve varenicline potency. In most cases, better varenicline potency was accompanied by an unwanted increase in ACh sensitivity (Fig. S3B,C). Nevertheless, for varenicline, but not tropisetron, some combinations were agonist-type selective: Gln139→Leu and Tyr217→Phe reduced ACh potency and enhanced varenicline potency (Fig. S3D). The triple mutant α7L131G,Q139L,Y217F-GlyR dramatically improved varenicline potency (EC50MP: 1.6 ± 0.1 nM), which is 390-fold more potent than at the parent α7-GlyR channel (Fig. 2C). Competition binding by displacement of the selective α7 nAChR antagonist, [3H]-ASEM (24), with varenicline showed Ki: 1.3 ± 0.4 nM at α7L131G,Q139L,Y217F-GlyR (Fig. S4A), which is 475-fold lower than the reported Ki of varenicline at α7 nAChR (25). In electrophysiological recordings from HEK-293 cells expressing α7L131G,Q139L,Y217F-GlyR, varenicline was a strong agonist (Fig. S4B,C, IVAR/IACh = 1.9 ± 0.2, n = 13) that produced a slowly activating response, with a sustained window current balancing channel activation and inactivation, and slow ligand off rate due to the high affinity interaction (Fig. 2D, S4D). Similar response properties were also observed in an immune cell line (Fig. S4E,F), demonstrating that channel function is comparable in another cell type. Varenicline had 160-fold agonist selectivity at α7L131G,Q139L,Y217F-GlyR over the drug’s clinical target, α4β2 nAChR (Fig. S4G) and was 880-fold more potent than at 5HT3-R (Fig. S4H), indicating a good window for selective chemogenetic agonism with this drug.

The α7L131G,Q139L,Y217F-GlyR chimeric channel also had 13-fold reduced ACh potency (EC50MP: 83 ± 20 μM), which is nearly 100,000-fold higher than basal mouse brain ACh levels (0.9 nM) (26). This is higher than measurements of transient ACh rises in the brain, which reach 1 – 2 μM (27) and do not activate the channel (Fig. S4I,J). The remarkably slow activation of α7-GlyR chimeric channels (28) (Fig. S4I) serves as a temporal filter for fast ACh transients. Choline responsiveness was also low (EC50MP: 128 ± 32 μM) (Fig. S4K-M), requiring concentrations substantially higher than brain or circulating plasma levels (0.54 to 7.8 μM) (29, 30).

The agonist potency of α7L131G,Q139L,Y217F-GlyR was enhanced for only a subset of α7 nAChR agonists but was reduced for others (Fig. 2B), indicating that the LBD modifications are selective for particular chemical structures, instead of a nonspecific reduction in channel activation energy. Blocking α7L131G,Q139L,Y217F-GlyR with the noncompetitive ion pore antagonist, picrotoxin (PTX), did not affect the voltage clamp holding current (Fig. S5A), demonstrating the absence of ligand-independent leak conductance (Fig. S5B). This contrasts with other channel variants that we made based on different designs that showed enhanced potency but also constitutive conductance (Fig. S6). In addition, α7L131G,Q139L,Y217F-GlyR did not respond to glycine nor did it inhibit endogenous glycine-gated GlyR currents (Fig. S5C-E). Because of high potency, selectivity, and lack of constitutive activity, the α7L131G,Q139L,Y217F ligand binding domain was selected as a chemogenetic tool that is activated by varenicline and named PSAM4.

Neuron silencing and activation ex vivo

To test PSAM4-GlyR as a neuronal silencer, we used in utero electroporation in mice to co-express the chemogenetic channel and EGFP in layer 2/3 cortical neurons (Fig. 2E). PSAM4-GlyR-expressing neuron properties in acute brain slices were similar to nearby untransfected control cells (Fig. S4M). Varenicline (10 – 16 nM) strongly suppressed firing (Fig. 2F) due to electrical shunting that, on average, reduced the input resistance by 3-fold (Fig. 2G) and increased the current amplitude required to fire an action potential by 6-fold (rheobase) (Fig. 2H), with multiple neurons not firing even with 500 pA depolarizing current. Silencing was reversible upon ligand washout, although not all cells fully recovered during the recording due to the slow off rate of varenicline from PSAM4-GlyR (Fig. 2D). We examined the durability of continuous silencing using cultured hippocampal neurons expressing PSAM4-GlyR under constant exposure to varenicline (15 nM) for 3 – 18 days, which maintained elevated rheobase that reversed on washout and could be re-silenced by re-application of varenicline (Fig. S5F-I). These low concentrations of varenicline for silencing are 2 – 13 times less than the estimated range of steady state brain concentrations of varenicline in humans from a twice daily 1 mg dose (18). This raises the possibility that varenicline can be used for chemogenetic applications at doses below those that are effective for anti-nicotine therapy.

For chemogenetic activation, we generated PSAM4-5HT3 (13), with the cation-selective conductance properties of the 5HT3 receptor. Varenicline was a partial agonist (Fig. S7A,B, IVAR/IACh= 0.17 ± 0.08) that activated long-lasting currents (Fig. 2I) with high potency (EC50MP: 4 ± 2 nM, Fig. 2I and S7C), and slow off-rates (t-off1/2: 3.2 ± 1.3 min). In contrast, the endogenous ligands, ACh and choline had low potencies at PSAM4-5HT3 (Fig. S7D and E). This ion channel-ligand combination can be used to gate a constant depolarizing current in cells. Sustained depolarization of cultured hippocampal neuron by PSAM4-5HT3 was durable for at least 14 – 22 d of continuous varenicline (15 nM) exposure (Fig. S7F,G). We also made a high conductance channel variant, PSAM4-5HT3 HC (13), and layer 2/3 cortical neurons expressing the channel (Fig. 2J) showed membrane properties similar to intermingled non-transfected neurons (Fig. S7H). Varenicline depolarized PSAM4-5HT3 HC-expressing cells (+17.2 ± 2.4 mV) (Fig. 2K) and led to action potential firing (Fig. 2L).

Chemogenetic silencing in mice and monkey

In vivo chemogenetic efficacy was tested with PSAM4-GlyR in mice by targeting Slc32a1 (vgat)-expressing GABAergic neurons in the substantia nigra reticulata (SNr) (Fig. 3A). Unilateral silencing of SNr neurons using intracranial microinjections of the GABA receptor agonist muscimol results in rotation contraversive to the inhibited side (31). For chemogenetic silencing, the SNr was transduced with PSAM4-GlyR by injection of rAAV1-Syn::FLEX-rev-PSAM4-GlyR—IRES—EGFP. The dose response of varenicline-mediated PSAM4-GlyR silencing was established by monitoring mouse rotation in the presence of low dose amphetamine (3 mg/kg) to increase overall activity. The lowest effective dose (LED) for onset of rotation activity in PSAM4-GlyR mice after intraperitoneal varenicline delivery was 0.1 mg/kg (Fig. 3B, Movie 1). Subsequent varenicline re-administration after 5 h reactivated rotation activity without tachyphylaxis of the chemogenetic response (Fig. 3C). Behavioral effects of silencing were evident within 20 min, and rotation activity returned nearly to baseline after 4 h (Fig. 3D), consistent with reported varenicline half-life (20). These low doses of varenicline are 10-fold lower than those required for mice to recognize varenicline as a replacement for nicotine (32, 33) or for other reported behavioral consequences in mice (34). In addition, oral delivery of varenicline (5 μg/mL) also elicited circling (Fig. S5K).

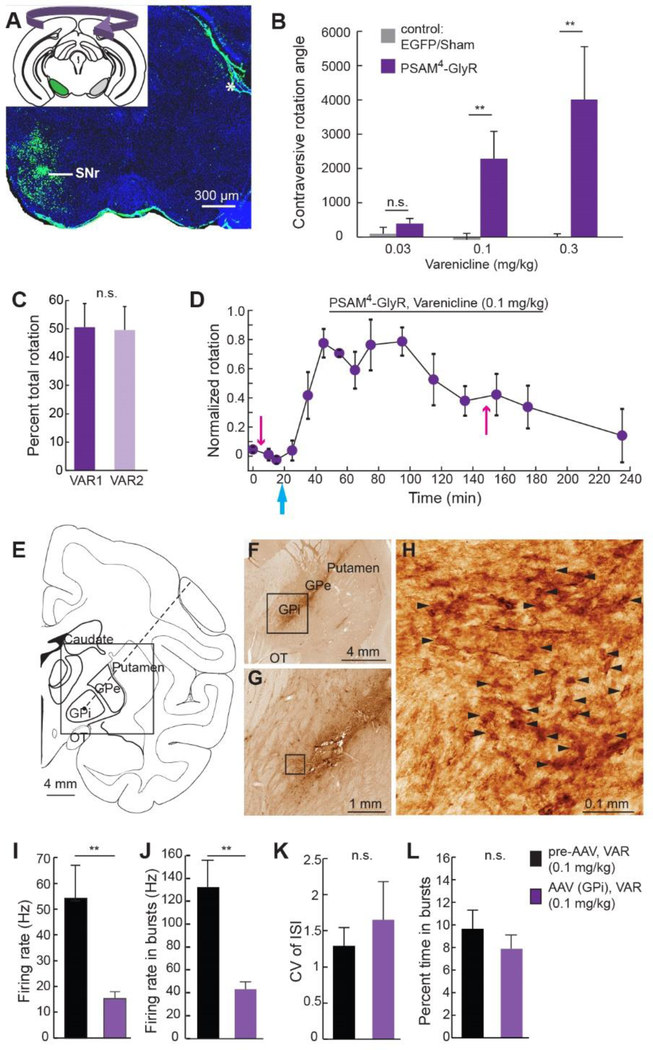

Figure 3.

PSAM4-GlyR neuron silencing in mice and a monkey. A) PSAM4-GlyR—IRES—EGFP targeted unilaterally to the SNr. Inset: schematic of unilateral SNr transduction and contralateral rotation. Asterisk: non-specific immunofluorescence. B) Low doses of intraperitoneal varenicline elicit contraversive rotation for mice expressing PSAM4-GlyR (n=9 mice) but not sham operated or EGFP-alone expressing mice (n=6 mice). C) Two doses of varenicline separated by 5 h give similar proportion of total rotation (n=4 mice). D) Timecourse of rotation response normalized to maximum rotation for each mouse (n=4 mice). Pink arrows: amphetamine injections, cyan arrow: varenicline injection. E) Coronal diagram of rhesus macaque brain showing location of GPi targeted for AAV injection and in vivo electrophysiological recordings along trajectory shown by dotted line. Box: area of interest for (F). OT:optic tract, GPi: internal globus pallidus, GPe: external globus pallidus. F-H) EGFP marker gene expression near injection site. Boxes denote area of interest for subsequent panel, arrowheads (H) indicate EGFP-positive neuronal profiles visualized by 3–3’-diaminobenzidine polymerization. (I-L) In one monkey, electrophysiological reduction of overall neuronal firing rate (I) and burst firing rate (J) in GPi after peripheral varenicline injection. Coefficient of variation of ISI (CV of ISI) (K) and percent time in burst firing (L) were not affected (pre-AAV: n=8 neurons, post-PSAM4-GlyR AAV: n=10 neurons). Error bars are SEM. Mann-Whitney U-test, n.s. P>0.05, **P<0.01.

We also tested PSAM4-GlyR for silencing activity in a rhesus monkey in the globus pallidus internal region (GPi) (Fig. 3E). GPi was transduced with PSAM4-GlyR by electrophysiologically guided injection of rAAV8-Syn::PSAM4-GlyR—IRES—EGFP (Fig. 3F-H). GPi neuron firing rate and burst firing rate were significantly inhibited by subcutaneous varenicline (0.1 mg/kg) delivery as compared to GPi activity in the presence of varenicline prior to AAV transduction (Fig. 3I,J). Neither the regularity of firing (CV for interspike interval) nor burst probability were affected by chemogenetic silencing (Fig. 3K,L). This dose is 5-fold lower than the dose required for varenicline to serve as a nicotine-substituting discriminative stimulus in monkeys (35).

Highly potent and selective chemogenetic agonists

Chemogenetic agonists for research applications should balance requirements for high potency, selectivity, and brain bioavailability along with pharmacodynamic responses of hours. We set out to make molecules that retained the high potency of varenicline at PSAM4 but improved selectivity over varenicline’s endogenous targets. We synthesized 30 varenicline analogs (Fig. 4A, Table S2) modified at the quinoxaline portion of the molecule because of its predicted proximity to the “hole” predicted by the Leu131→Gly mutation (Fig. 2A). We chose modifications that kept structural elements and physicochemical properties within ranges associated with brain bioavailability and low PgP substrate activity (36). Thirteen molecules had potency below 10 nM at PSAM4-GlyR or PSAM4-5HT3 and had high selectivity for PSAM4-GlyR with reduced agonist activity at the three endogenous targets of varenicline (α4β2 nAChR, α7 nAChR, and 5HT3-R) (Table S2).

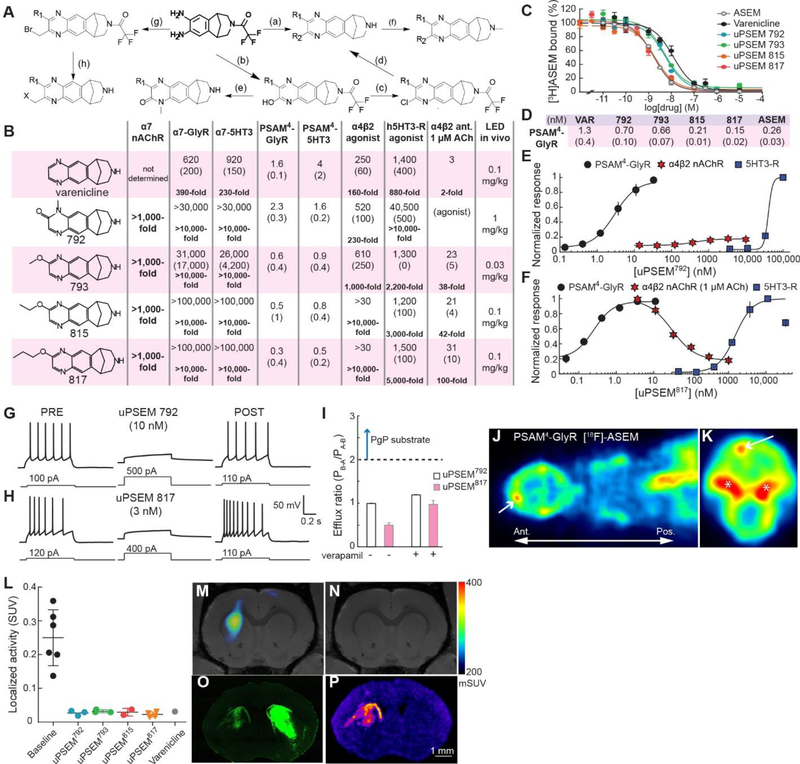

Figure 4.

Highly selective chemogenetic agonists. A) Synthetic pathways (letters) for uPSEM agonists (see Methods). B) Comparison of uPSEM agonist EC50s at PSAM4 channels and endogenous varenicline targets, as well as IC50 for α4β2 nAChR with 1 μM ACh. LED: lowest effective dose for mice in SNr rotation assay. Units: nM; parentheses: SEM. Selectivity relative to PSAM4-GlyR in bold. C,D) Displacement of [3H]ASEM at PSAM4-GlyR by uPSEMs (C) and Ki values (D). Units: nM. Parentheses: SEM. E,F) Dose response curves for PSAM4-GlyR, α4β2 nAChR, 5HT3-R. uPSEM792 (E) is a 10% partial agonist of α4β2 nAChR and uPSEM817 (F) inhibits α4β2 nAChR. G,H) uPSEM 792 (G) and uPSEM817 (H) strongly suppress firing in neurons expressing PSAM4-GlyR. I) Efflux ratio<2, indicating uPSEM792 and uPSEM817 are not PgP substrates. PB-A and PA-B are basal and apical permeability across Caco-2 cell line monolayer (n = 2 replicates). J,K) In vivo PET imaging after [18F]-ASEM injection showing cortical localization of PSAM4-GlyR in horizontal view through head and upper torso (J) and coronal view of the head (K). Arrow shows site of PSAM4-GlyR expression. Asterisks show accumulation of [18F] outside the brain. (L) [18F]-ASEM binding to PSAM4-GlyR under baseline conditions and with competition by uPSEMs and varenicline. uPSEM792 (1 mg/kg), uPSEM793 (0.3 mg/kg), uPSEM815 (0.3 mg/kg), uPSEM817 (0.3 mg/kg), varenicline (0.3 mg/kg). M) Tomographic plane showing [18F]-ASEM binding to PSAM4-GlyR in vivo. N) Competition of [18F]-ASEM binding by intraperitoneally administered uPSEM792. O,P) Ex vivo fluorescence image (O) and autoradiographic image of [3H]-ASEM binding (P) of corresponding brain slice expressing PSAM4-GlyR—IRES—EGFP in left dorsal striatum. Right striatum was injected with EGFP-alone expressing virus. Error bars are SEM.

We focused on four molecules that had high potency in mice (Fig. 4B, Table S2 and below). Quinoxalone derivative 792 (Fig. 4A, pathway e) had sub-nanomolar affinity for PSAM4-GlyR (Ki: 0.7 ± 0.1 nM) (Fig. 4C,D) and was an ultrapotent PSEM (uPSEM) agonist for PSAM4-GlyR and PSAM4-5HT3 (Fig. 4B,E, S8A,B). uPSEM792 showed >10,000-fold agonist selectivity for PSAM4 over α7-GlyR, α7–5HT3, and 5HT3-R (4B,E, S8C). At α4β2 nAChR, uPSEM792 was a very weak partial agonist (10 ± 0.4%) (Fig. S8D, S9A) with 230-fold selectivity for PSAM4-GlyR (Fig. 4B,E). Thus, uPSEM792 retained the potency of varenicline for PSAM4-GlyR with enhanced chemogenetic selectivity.

Alkoxy-substitution of varenicline (Fig. 4A, pathway d) resulted in sub-nanomolar PSAM4-GlyR affinities and potencies (Fig. 4B, S8E,G,I). The highest affinity PSAM4-GlyR agonist, uPSEM817 (Ki: 0.15 ± 0.02 nM) (Fig. 4C), was generated by propoxy substitution of varenicline and has remarkable potency (EC50MP: 0.3 ± 0.4 nM), which makes uPSEM817 one of the most potent LGIC agonists ever reported. uPSEM817 agonist selectivity is also excellent, with 5000-fold to 10,000-fold selectivity for PSAM4-GlyR over α7-GlyR, α7–5HT3, and 5HT3-R (Fig. 4B). uPSEM815 and uPSEM817 do not show evident α4β2 nAChR agonism up to 30 μM (Fig S9B), and uPSEMs 793 and 815 have >2000-fold selectivity for PSAM4-GlyR over 5HT3-R (Fig. 4B, S8F,H). α7 nAChR agonism was not detected for any of the uPSEMs at 1000-fold their PSAM4-GlyR EC50s (Fig. S9C,D).

To test for binding to a larger range of molecular targets, we used radioligand displacement against functionally important endogenous receptors and transporters (37). This showed no significant binding at 30-fold to 100-fold the PSAM4-GlyR EC50 of the uPSEMs at 48/52 targets, including serotonin, GABA, adrenergic, muscarinic, dopamine, and histamine receptors (Tables S3 and S4). [3H]-ASEM radioligand displacement from rat forebrain tissue α7 nAChRs by uPSEMs showed high Ki values of 0.3 – 8 μM (Fig. S9E). The molecules retain binding to β2-containing nAChRs, with highest affinity for α4β2 nAChR (Table S3, S4, Fig. S9E). However, for uPSEM792, functional measurements of α4β2 channel activation by 1 μM ACh (a low but physiologically relevant concentration) did not show inhibitory consequences of uPSEM792 before the higher concentrations at which uPSEM792 elicits weak α4β2 agonist activity (Fig. S9A), and the IC50 for uPSEM817 at α4β2 nAChR is 100-fold higher than its EC50 for PSAM4-GlyR (Fig. 4B,F).

uPSEMs 792, 793, 815, 817 strongly suppressed layer 2/3 cortical neurons expressing PSAM4-GlyR in brain slices at low concentrations ranging from 1–15 nM (Fig. 4G, S9G-K). In addition, all uPSEMs were soluble in water. We tested the most selective uPSEMs 792 and 817 for P-glycoprotein pump efflux. They were not PgP substrates (Efflux ratio < 2, Fig. 4I, Table S5), indicating that they are suitable candidates for in vivo applications in the brain.

Imaging chemogenetic receptors in vivo

Delivery of chemogenetic receptors to the brain can be variable, thus it is desirable to non-invasively monitor chemogenetic receptor expression and anatomical distribution in the brain. To non-invasively measure the distribution of PSAM4-GlyR in vivo as well as accessibility and binding of uPSEMs in the mouse brain we employed positron emission tomography (PET). PSAM4-GlyR expressed unilaterally in the cortex potently bound the radiolabeled α7 nAChR antagonist, [18F]-ASEM (38), at this location in vivo (Fig. 4J,K). Receptor localization could be readily visualized against endogenous ligand binding, even with extremely low doses of the tracer. The distribution of PSAM4-GlyR can thus be determined non-invasively with a PET ligand that has been used in humans and is suitable for both research and clinical applications.

To establish uPSEM binding to PSAM4-GlyR in brain tissue, we used radioligand displacement. PSAM4-GlyR—IRES—EGFP was expressed in the left dorsal striatum and EGFP alone was expressed in the right striatum. We performed autoradiography with [3H]-ASEM bound to PSAM4-GlyR in striatal brain slices to confirm ligand displacement ex vivo (Fig. S9M-O), and the radioactivity corresponded to the location of PSAM4-GlyR—IRES—EGFP expression (Fig. S9P). Next, we established brain penetrance and receptor binding of uPSEMs in vivo using PET by competition of [18F]-ASEM binding with intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of uPSEM agonists (Fig. 4L). [18F]-ASEM binding in the left dorsal striatum (Fig. 4M), was eliminated by injection of these agonists (Fig. 4N). The in vivo [18F]-ASEM localization matched ex vivo expression of PSAM4-GlyR—IRES—EGFP established by post hoc fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4O) as well as [3H]-ASEM autoradiography (Fig. 4P) in the same tissue sections, but binding was not observed in the right striatum, which expressed EGFP-alone.

Potent uPSEM neuron silencing in vivo

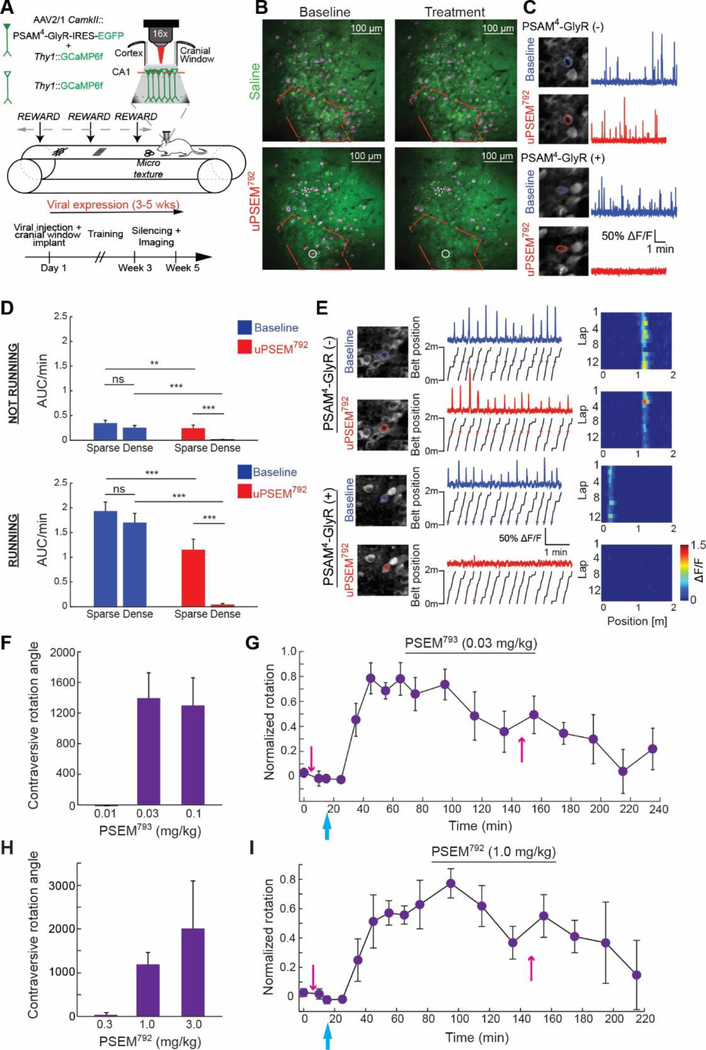

To directly monitor uPSEM792-mediated neuronal silencing in vivo, we recorded calcium dynamics of hippocampal neurons in area CA1 by 2-photon imaging in head fixed mice running on a treadmill marked with texture cues (Fig. 5A). In a Thy1::GCaMP6f transgenic mouse, PSAM4-GlyR was expressed in hippocampal pyramidal cells by injection of rAAV1-CamkII::PSAM4-GlyR—IRES—EGFP (Fig. 5A). The field of view contained distinct domains of neurons densely and sparsely transduced with PSAM4-GlyR—IRES—EGFP (Fig. 5B). In stationary and running behavioral epochs, which elicit different levels of CA1 activity, both domains showed similar baseline activity, indicating that expression of PSAM4-GlyR did not perturb basal activity (Fig. 5C,D). After intraperitoneal injection of uPSEM792 (3 mg/kg), the densely transduced CA1 hippocampal domains were strongly silenced, while the sparsely transduced domain showed a modest reduction in activity (Fig. 5C,D). In mice not expressing PSAM4-GlyR, we found no significant difference in calcium activity of CA1 pyramidal neurons following administration of uPSEM792 at 3 mg/kg (p=0.9515, n=265 neurons, 3 mice, 93.5% of median baseline activity, signed rank test). Place cells, which fire due to powerful circuit and cell autonomous conductances, were also silenced by PSAM4-GlyR and uPSEM792 (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5.

Neuron silencing with uPSEMs and PSAM4-GlyR in vivo. (A) Experimental design for monitoring hippocampal CA1 neuron silencing with PSAM4-GlyR and uPSEM792 using in vivo two photon Ca2+ imaging in head-fixed mice running on a treadmill with textural landmarks. PSAM4-GlyR—IRES—EGFP was virally expressed in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons in Thy1-GCaMP6f mice. Neurons co-expressing GCaMP6f and viral PSAM4-GlyR—IRES—EGFP are solid green, while neurons expressing only GCaMP6f are green outline. (B) Z-stack projections (green) overlaid with maximum intensity projections of GCaMP6f fluorescence in time (magenta) overlaid with an example from a saline treated (top) and uPSEM792 treated (bottom) mouse. Red outline encloses densely transduced region, which also shows strong uPSEM792-mediated reduction of neuron activity (reduced magenta signals). Outside the red boundary is the sparsely transduced region. Neurons depicted in (C) are circled. (C) Representative ROIs (left) and somatic Ca2+ traces (right). Transduced PSAM4-GlyR(+) pyramidal neurons are identified by EGFP-filled somata, whereas PSAM4-GlyR(−) cells have only cytoplasmic GCaMP6f fluorescence. (D) Activity rate (area under ΔF/F trace of Ca2+ transients divided by epoch duration (AUC/min)) for episodes in which mice were running and not running on the treadmill. Densely transduced: run, n = 68 neurons, no-run, n = 58 neurons from 2 mice; sparsely transduced: run, n= 103 neurons, no-run, n= 96 neurons from 2 mice. Mann-Whitney U-test and signed rank test with Holm-Sidak correction. (E) Place field activity following uPSEM792 administration. Somatic ROI outlines before and after treatment (left), ΔF/F activity (center top) with associated position of the mouse on the belt (center bottom), and raster plots with mean ΔF/F activity in each 2 cm spatial bin across laps (right). Asterisks denote the location of significant running calcium transients along the belt. (F-I) In vivo uPSEM dose responses for mice (n = 4) expressing PSAM4-GlyR unilaterally in SNr. Behavioral response and timecourse for uPSEM793 (F,G) and uPSEM792 (H,I). Time course of rotation response normalized to maximum rotation for each mouse. Pink arrows: amphetamine injections, blue arrow: uPSEM injection. Error bars are SEM. n.s. P>0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Finally, to determine dose responses for uPSEMs in vivo, we used behavioral assays by measuring contralateral rotation in mice with the unilateral SNr silencing assay. The potency in mice was exceptional for uPSEM793 (LED: 0.03 mg/kg) (Fig. 5F,G), which is a 1000-fold improvement on first-generation PSEMs (Movie 2). One of the most selective agonists, uPSEM792 was active at a lowest effective dose (LED) of 1 mg/kg in vivo (Fig. 5H,I, Movie 2). uPSEM817 also has a favorable selectivity profile and the same LED (0.1 mg/kg) as varenicline (Fig. S10, Movie 2). These low doses reflect the most selective silencing regime for these molecules. All molecules elicited durable responses of 3–4 h in mice with acute intraperitoneal dosing (Fig. 5G,I and S10), which was comparable to varenicline. To examine potential off-target behavioral effects of uPSEMs, we monitored food intake, which is sensitive to off-target 5HT3-R activation. Food consumption was not significantly altered by uPSEMs at 3-fold greater than the lowest effective doses determined in the SNr silencing assay, although food intake was reduced with elevated varenicline doses, highlighting the superior selectivity of uPSEMs (Fig. S11).

Discussion

Chemogenetics permits targeted, non-invasive, and reversible perturbations of cellular function. Here, we developed a set of modular ion channels and selective, exceptionally potent agonists that are effective in the brain for rodent and primate models. Novel chemogenetic agonists were derived from the clinically approved drug varenicline and required optimization to balance competing needs for potency, selectivity, brain penetrance, and response times of hours. We determined lowest effective doses of the uPSEMs and varenicline in vivo to achieve the optimal balance of efficacy and selectivity. Importantly, the clinically approved drug varenicline can also be used for chemogenetics at lower concentrations than those associated with anti-nicotine clinical applications (18).

The effectiveness, ease-of-use, and targeted nature of chemogenetics have made clinical applications attractive (3, 4, 39). Chemogenetics uses a limited repertoire of drug/receptor pairs but achieves diverse therapeutic effects by targeting the receptors via gene transfer to distinct regions. This offers a model for therapy that circumvents the pharmacological complexity of protein target identification followed by drug development for each new target. Our engineered ion channel technology facilitates chemogenetic therapies because it uses a well-tolerated approved drug that can potentially be used at or below doses for which it is currently approved. Clinical applications of chemogenetics are well suited for conditions that can be ameliorated by modulating cellular activity at localized sites to which the chemogenetic receptor can be delivered in the course of standard surgical procedures, such as pharmacotherapy-refractory localized pain, focal epilepsy, and some movement disorders (4, 39, 40). Indeed, we showed chemogenetic perturbations in two nodes of the basal ganglia that are associated with invasive Parkinson’s Disease deep brain stimulation therapies. Additional studies will be needed to establish long-term safety and efficacy with chemogenetic receptors for therapeutic applications, but this is facilitated by the current clinical use of varenicline. These chemogenetic technologies offer opportunities in basic research and the capability for extending findings to potential therapeutic applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Jon Lindstrom for providing stable cell lines expressing human α4β2 nAChR or α7 nAChR. Receptor counter-screening and associated Ki determinations were generously provided by the National Institute of Mental Health’s Psychoactive Drug Screening Program, Contract # HHSN-271–2013-00017-C (NIMH PDSP). We are grateful for support from Janelia core facility staff; Sarah Lindo performed in utero electroporations.

Funding: S.M.S., C.M., P.L., and M.R. were funded by HHMI. X.H. and A.G. was supported by grant NIH ORIP OD P51-OD011132 to the Yerkes National Primate Research Center. J.B. was supported by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, Klingenstein-Simons Foundation, NIH NINDS 1R01 NS109362–01, and Whitehall Foundation. M.M. is funded through NIDA IRP (ZIA000069).

Footnotes

Competing interests: S.M.S., C.J.M., and P.H.L. have pending patents on this technology and own stock in Redpin Therapeutics, LLC, which is a biotech company focusing on therapeutic applications of chemogenetics. S.M.S. is a cofounder and consultant for Redpin Therapeutics. M.M. is a cofounder and owns stock in Metis Laboratories, Inc.

Data and materials availability: All data to support the conclusions of this manuscript are included in the main text and supplementary materials. Plasmids and AAV vectors are available from www.addgene.com. Accession numbers are PSAM4-GlyR (MK492109), PSAM4-5HT3 (MK492107), PSAM4-5HT3 HC (MK492108). uPSEM792 and uPSEM817 are available from Tocris.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Sternson SM, Roth BL, Chemogenetic tools to interrogate brain functions. Annu. Rev. Neurosci 37, 387–407 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atasoy D, Sternson SM, Chemogenetic Tools for Causal Cellular and Neuronal Biology. Physiol. Rev. 98, 391–418 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.English JG, Roth BL, Chemogenetics-A Transformational and Translational Platform. JAMA neurology 72, 1361–1366 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katzel D, Nicholson E, Schorge S, Walker MC, Kullmann DM, Chemical-genetic attenuation of focal neocortical seizures. Nature communications 5, 3847 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez JL et al. , Chemogenetics revealed: DREADD occupancy and activation via converted clozapine. Science 357, 503–507 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raper J et al. , Metabolism and Distribution of Clozapine-N-oxide: Implications for Nonhuman Primate Chemogenetics. ACS Chem Neurosci, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacLaren DA et al. , Clozapine-n-oxide administration produces behavioral effects in Long-Evans rats - implications for designing DREADD experiments. eneuro, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexander GM et al. , Remote control of neuronal activity in transgenic mice expressing evolved G protein-coupled receptors. Neuron 63, 27–39 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL, Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 5163–5168 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jann MW, Lam YW, Chang WH, Rapid formation of clozapine in guinea-pigs and man following clozapine-N-oxide administration. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther 328, 243–250 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wenthur CJ, Lindsley CW, Classics in chemical neuroscience: clozapine. ACS Chem Neurosci 4, 1018–1025 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roth BL, DREADDs for Neuroscientists. Neuron 89, 683–694 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magnus CJ et al. , Chemical and genetic engineering of selective ion channel-ligand interactions. Science 333, 1292–1296 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macor JE et al. , The 5-HT3 antagonist tropisetron (ICS 205–930) is a potent and selective alpha7 nicotinic receptor partial agonist. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 11, 319–321 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mihalak KB, Carroll FI, Luetje CW, Varenicline is a partial agonist at alpha4beta2 and a full agonist at alpha7 neuronal nicotinic receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 801–805 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura M et al. , Efficacy and tolerability of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, in a 12-week, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-response study with 40-week follow-up for smoking cessation in Japanese smokers. Clin. Ther. 29, 1040–1056 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaur K, Kaushal S, Chopra SC, Varenicline for smoking cessation: A review of the literature. Current therapeutic research, clinical and experimental 70, 35–54 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rollema H et al. , Pre-clinical properties of the alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonists varenicline, cytisine and dianicline translate to clinical efficacy for nicotine dependence. Br. J. Pharmacol. 160, 334–345 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faessel HM et al. , Lack of a pharmacokinetic interaction between a new smoking cessation therapy, varenicline, and digoxin in adult smokers. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 64, 1101–1109 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obach RS et al. , Metabolism and disposition of varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, in vivo and in vitro. Drug Metab. Dispos. 34, 121–130 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lummis SC, Thompson AJ, Bencherif M, Lester HA, Varenicline is a potent agonist of the human 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 339, 125–131 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rucktooa P et al. , Structural characterization of binding mode of smoking cessation drugs to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors through study of ligand complexes with acetylcholine-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 23283–23293 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hibbs RE et al. , Structural determinants for interaction of partial agonists with acetylcholine binding protein and neuronal alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Embo j 28, 3040–3051 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horti AG et al. , 18F-ASEM, a radiolabeled antagonist for imaging the alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with PET. J. Nucl. Med. 55, 672–677 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coe JW et al. , 3,5-Bicyclic aryl piperidines: a novel class of alpha4beta2 neuronal nicotinic receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 15, 4889–4897 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uutela P, Reinila R, Piepponen P, Ketola RA, Kostiainen R, Analysis of acetylcholine and choline in microdialysis samples by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 19, 2950–2956 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parikh V, Kozak R, Martinez V, Sarter M, Prefrontal acetylcholine release controls cue detection on multiple timescales. Neuron 56, 141–154 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grutter T et al. , Molecular tuning of fast gating in pentameric ligand-gated ion channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 18207–18212 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffith CA, Owen LJ, Body R, McDowell G, Keevil BG, Development of a method to measure plasma and whole blood choline by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Annals of clinical biochemistry 47, 56–61 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yue B et al. , Choline in Whole Blood and Plasma: Sample Preparation and Stability. Clin. Chem. 54, 590–593 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheel-Krüger J, Arnt J, Magelund G, Behavioural stimulation induced by muscimol and other GABA agonists injected into the substantia nigra. Neurosci. Lett. 4, 351–356 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cunningham CS, McMahon LR, Multiple nicotine training doses in mice as a basis for differentiating the effects of smoking cessation aids. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 228, 321–333 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Moura FB, McMahon LR, The contribution of alpha4beta2 and non-alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors to the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine and varenicline in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 234, 781–792 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ortiz NC, O’Neill HC, Marks MJ, Grady SR, Varenicline blocks beta2*-nAChR-mediated response and activates beta4*-nAChR-mediated responses in mice in vivo. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco 14, 711–719 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cunningham CS, Javors MA, McMahon LR, Pharmacologic characterization of a nicotine-discriminative stimulus in rhesus monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 341, 840–849 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hitchcock SA, Structural modifications that alter the P-glycoprotein efflux properties of compounds. J. Med. Chem. 55, 4877–4895 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Besnard J et al. , Automated design of ligands to polypharmacological profiles. Nature 492, 215–220 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong DF et al. , Human brain imaging of alpha7 nAChR with [(18)F]ASEM: a new PET radiotracer for neuropsychiatry and determination of drug occupancy. Molecular imaging and biology : MIB : the official publication of the Academy of Molecular Imaging 16, 730–738 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weir GA et al. , Using an engineered glutamate-gated chloride channel to silence sensory neurons and treat neuropathic pain at the source. Brain 140, 2570–2585 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hirschberg S, Li Y, Randall A, Kremer EJ, Pickering AE, Functional dichotomy in spinal-vs prefrontal-projecting locus coeruleus modules splits descending noradrenergic analgesia from ascending aversion and anxiety in rats. Elife 6, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vong L et al. , Leptin action on GABAergic neurons prevents obesity and reduces inhibitory tone to POMC neurons. Neuron 71, 142–154 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dana H et al. , Thy1-GCaMP6 transgenic mice for neuronal population imaging in vivo. PLoS One 9, e108697 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Atasoy D, Aponte Y, Su HH, Sternson SM, A FLEX switch targets Channelrhodopsin-2 to multiple cell types for imaging and long-range circuit mapping. J. Neurosci. 28, 7025–7030 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Audiffred JF, De Leo SE, Brown PK, Hale-Donze H, Monroe WT, Characterization and applications of serum-free induced adhesion in Jurkat suspension cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 106, 784–793 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campling BG, Kuryatov A, Lindstrom J, Acute activation, desensitization and smoldering activation of human acetylcholine receptors. PLoS One 8, e79653 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuryatov A, Mukherjee J, Lindstrom J, Chemical chaperones exceed the chaperone effects of RIC-3 in promoting assembly of functional alpha7 AChRs. PLoS One 8, e62246 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suter BA et al. , Ephus: multipurpose data acquisition software for neuroscience experiments. Frontiers in Neuroscience 5, 1–12 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brewer GJ, Isolation and culture of adult rat hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. Methods 71, 143–155 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song W, Chattipakorn SC, McMahon LL, Glycine-gated chloride channels depress synaptic transmission in rat hippocampus. J Neurophysiol 95, 2366–2379 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Osborne JE, Dudman JT, RIVETS: a mechanical system for in vivo and in vitro electrophysiology and imaging. PLoS One 9, e89007 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pnevmatikakis EA et al. , Fast spatiotemporal smoothing of calcium measurements in dendritic trees. PLoS Comput Biol 8, e1002569 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giovannucci A et al. , CaImAn an open source tool for scalable calcium imaging data analysis. Elife 8, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jia H, Rochefort NL, Chen X, Konnerth A, In vivo two-photon imaging of sensory-evoked dendritic calcium signals in cortical neurons. Nat Protoc 6, 28–35 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaremba JD et al. , Impaired hippocampal place cell dynamics in a mouse model of the 22q11.2 deletion. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 1612–1623 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dombeck DA, Khabbaz AN, Collman F, Adelman TL, Tank DW, Imaging large-scale neural activity with cellular resolution in awake, mobile mice. Neuron 56, 43–57 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Danielson NB et al. , Sublayer-Specific Coding Dynamics during Spatial Navigation and Learning in Hippocampal Area CA1. Neuron 91, 652–665 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kay K et al. , A hippocampal network for spatial coding during immobility and sleep. Nature 531, 185–190 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garber JC et al. , Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. (National Academies Press, Washington, DC, ed. 8th, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 59.DeLong MR, Activity of pallidal neurons during movement. J Neurophysiol 34, 414–427 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Galvan A, Hu X, Smith Y, Wichmann T, Localization and pharmacological modulation of GABA-B receptors in the globus pallidus of parkinsonian monkeys. Experimental neurology 229, 429–439 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Galvan A et al. , GABAergic modulation of the activity of globus pallidus neurons in primates: in vivo analysis of the functions of GABA receptors and GABA transporters. J Neurophysiol 94, 990–1000 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kliem MA, Wichmann T, A method to record changes in local neuronal discharge in response to infusion of small drug quantities in awake monkeys. Journal of neuroscience methods 138, 45–49 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Galvan A, Hu X, Smith Y, Wichmann T, Localization and function of GABA transporters in the globus pallidus of parkinsonian monkeys. Experimental neurology 223, 505–515 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Galvan A et al. , Localization and function of dopamine receptors in the subthalamic nucleus of normal and parkinsonian monkeys. J Neurophysiol 112, 467–479 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Galvan A, Hu X, Smith Y, Wichmann T, Effects of Optogenetic Activation of Corticothalamic Terminals in the Motor Thalamus of Awake Monkeys. J Neurosci 36, 3519–3530 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Samson AL et al. , MouseMove: an open source program for semi-automated analysis of movement and cognitive testing in rodents. Scientific reports 5, 16171 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen X et al. , The First Structure–Activity Relationship Studies for Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs. ACS Chemical Neuroscience 6, 476–484 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Allen SR, Oswald I, The effects of perlapine on sleep. Psychopharmacologia 32, 1–9 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vardy E et al. , A New DREADD Facilitates the Multiplexed Chemogenetic Interrogation of Behavior. Neuron 86, 936–946 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hooker JM et al. , Pharmacokinetics of the potent hallucinogen, salvinorin A in primates parallels the rapid onset and short duration of effects in humans. Neuroimage 41, 1044–1050 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Slimko EM, McKinney S, Anderson DJ, Davidson N, Lester HA, Selective electrical silencing of mammalian neurons in vitro by the use of invertebrate ligand-gated chloride channels. J. Neurosci. 22, 7373–7379 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Frazier SJ, Cohen BN, Lester HA, An Engineered Glutamate-gated Chloride (GluCl) Channel for Sensitive, Consistent Neuronal Silencing by Ivermectin. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 21029–21042 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pouliot JF, L’Heureux F, Liu Z, Prichard RK, Georges E, Reversal of P-glycoprotein-associated multidrug resistance by ivermectin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 53, 17–25 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kwei GY et al. , Disposition of Ivermectin and Cyclosporin A in CF-1 Mice Deficient in mdr1a P-Glycoprotein. Drug Metab. Dispos. 27, 581–587 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Trailovic SM, Nedeljkovic JT, Central and peripheral neurotoxic effects of ivermectin in rats. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 73, 591–599 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baraka OZ et al. , Ivermectin distribution in the plasma and tissues of patients infected with Onchocerca volvulus. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 50, 407–410 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guler AD et al. , Transient activation of specific neurons in mice by selective expression of the capsaicin receptor. Nature communications 3, 746 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Atasoy D, Betley JN, Su HH, Sternson SM, Deconstruction of a neural circuit for hunger. Nature 488, 172–177 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.