Abstract

There is limited global evidence exploring perceptions of dementia among people with intellectual disabilities. This article presents findings from the first known study where an inclusive research team, including members with intellectual disability, used photovoice methodology to visually represent views of people with intellectual disabilities and dementia. Drawing on Freire’s empowerment pedagogy, the study aims were consistent with global photovoice aims: enabling people to visually record critical dialogue about dementia through photography and social change. We investigated the benefits and challenges of photovoice methodology with this population and sought to identify perspectives of dementia from people with intellectual disabilities. Data collected identified issues such as peers “disappearing” and the importance of maintaining friendship as dementia progressed. Although reaching policymakers is a key aim of photovoice, this may not always be achievable, suggesting that revisiting Freire’s original methodological aims may lead to improved outcomes in co-produced research with marginalized groups.

Keywords: learning disability, disability, disabled persons, dementia, minorities, cultural competence, qualitative, Scotland, photovoice, participatory action research

Background

Dementia is a pressing health issue for people with intellectual disabilities, who are at greater risk of developing the condition at a younger age than the global population generally (McCarron et al., 2014). This is specifically an issue for people with Down syndrome, at least one third of whom will develop dementia in their 50s with more than half affected above the age of 60. Indeed, dementia is associated with mortality of 70% among older people with Down syndrome (Hithersay et al., 2019). This compares with dementia prevalence rate of 7.1% in the population without an intellectual disability aged above 65 (Prince et al., 2014). Alongside increased prevalence rates, in many countries, people with intellectual disabilities continue to be marginalized from mainstream spaces of employment, research, residence, and leisure, leading to lives often centered around intellectual disability-exclusive spaces (World Bank, 2019). However, there has been a dearth of research exploring the understanding and experiences of dementia in people with intellectual disabilities, whether having a diagnosis themselves or having a friend, family member, or partner with a diagnosis (Watchman & Janicki, 2019).

Within intellectual disability research, participatory approaches were developed in the late 1980s and early 1990s when disabled people, alongside academics, sought to develop research methods that did not perpetuate oppression (Oliver, 1992). See Note 1. This subsequently became characterized by greater meaningful participation and control by people with intellectual disabilities (Walmsley & Johnson, 2003). Key priorities for non-disabled researchers included a commitment and focus toward genuine engagement and participation, a challenge to traditional research relationships, inclusive design, and ensuring a strong voice for people with intellectual disabilities (Dorozenko et al., 2016; Dowse, 2009; Schwartz et al., 2019). This process has been challenged at times, for example, by Bigby and Frawley (2010) with questions asked about ownership and control of studies, and genuineness of involvement in research.

A growing body of research has emerged using photovoice with people who have intellectual disabilities particularly in Europe and the United States. Photovoice is a participatory method in which the individual observes their everyday realities or the reality of others, and then takes photographs to discuss the meanings behind those images (Baker & Wang, 2006). This is under the premise that it is often impossible to understand the meaning of an image in isolation from the context in which it emerged (Aldridge, 2007). Images can give a different perspective on the world than one that is represented through words (Harper, 2012). While photovoice has become increasingly recognized as an accessible method to involve people with intellectual disabilities in research (Aldridge, 2007; Booth & Booth, 2003; Povee et al., 2014), no known studies have used this approach to explore dementia in people with intellectual disability. This article highlights the work of an inclusive research team, including members with an intellectual disability, who used photovoice methodology to uniquely demonstrate how people with intellectual disability can take control of their own narrative.

Photovoice Theory

One of the key theories in shaping photovoice, Freire’s (1970, 2014) empowerment pedagogy, reflects the need for inclusivity and change. He argued that critical thinking is best generated by means of group discussion of images within a group, with photographs acting as a mirror to communities and reflecting everyday realities. Based in Brazil, Freire believed that through a collective process of reflection and discussion of images, communities would be able to uncover constructs that maintain their marginalization. He identified three levels of consciousness. The first is the “magical” level, where people accept their social positioning and status quo without any resistance. At the second, “naive” level, individuals perceive their social situation as sound but unfair. Individuals who achieve critical consciousness, the third level, become aware of both the ways in which contexts are structured to maintain oppression. This third level offers a deeper understanding of how society and power relationships affect an individual’s situation to explore ways in which they can contribute to change through their own actions. However, this change cannot be achieved by individuals alone, with a requirement for community members to work together for meaningful change. Wang and Burris (1997) in the United States extended Freire’s principles and encouraged participants to engage with those in power to facilitate social change. The photo stories then become a platform from which researchers can offer a nuanced understanding of community issues to the scientific community: an advance that can inform appropriate intervention or action on health and social issues.

Scoping Review

We conducted a scoping review to provide broad contextual and contemporary evidence about the use of photovoice methodology with both people who have dementia and people who have an intellectual disability. This included international work published between 2003 and 2019 and consisted of peer-reviewed journals excluding systematic reviews, and externally examined thesis in English. The initial screening from title and abstract was completed by one member of the team with both first and second reviewer independently repeating the screening of full texts and a third reviewer seeking consensus as needed over any disagreement. Material produced prior to 2003 was excluded due to the need to develop new evidence based on contemporary material. The study only included peer-reviewed or externally reviewed articles; however, given the intention of identifying positive approaches and ways of overcoming barriers to inclusion in advance of the study, it was felt important to focus on international work that had been scrutinized by peer review or stringent external examination such as academic thesis. See Note 2.

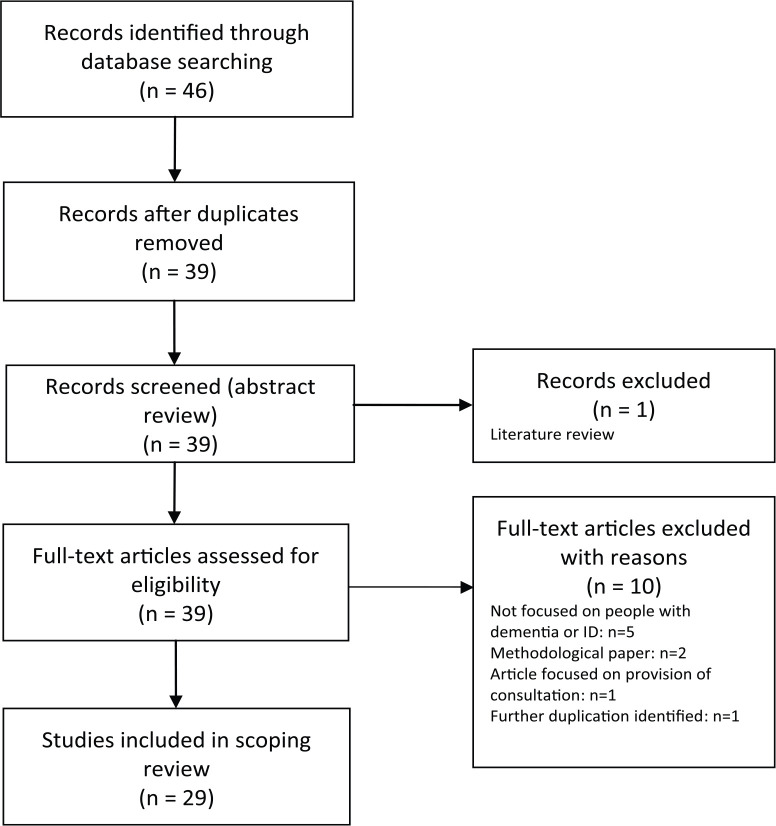

In conducting the scoping review, we aimed to highlight the evidence of use of photovoice around the world with both people with dementia and people with intellectual disability consistent with Arksey and O’Malley’s (2007) five-stage framework to guide the iterative, reflexive, and developmental approach to the review (Figure 1). See also supplementary file 1 for full scoping review.:

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

Identifying the research question;

Identifying relevant studies;

Study selection;

Charting the data;

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

The reported benefits of photovoice methodology identified through the scoping review were diverse. Photo-voice was framed as enabling a more active collaboration between researcher and participants than more traditional research would have afforded (Heffron et al., 2018). Concepts of participant “empowerment” were also widely documented although the term was not always explained (Ataie, 2014; Bossler, 2016; Brake et al., 2012; Dorozenko et al., 2015; Guerra et al., 2013; Overmars-Marx et al., 2018; Povee et al., 2014; Walton et al., 2012; Weiss et al., 2017). There was a tendency to focus on individual empowerment within the research process, with participants becoming more empowered to take action at the individual level (Bossler, 2016) and to share their stories within their local communities (Bossler, 2016; Brake et al., 2012; Guerra et al., 2013). Wider community reach and impact typically centered around public photography displays (Brake et al., 2012; Dorozenko et al., 2016; Walton et al., 2012). Very few studies considered the role of photovoice in initiating wider social action or change, although Walton et al. (2012), reporting on a community-based participatory research project, reflected on the importance of a continued collaboration between the university team and advocacy organization in driving forward wider impact with policymakers.

Numerous challenges were reported which suggested a need for a flexible and adapted approach. This included difficulties in obtaining information or reflections from participants (Booth & Booth, 2003), obtaining informed consent of people who appeared in the photographs (Cardell, 2015; Dorozenko et al., 2015; Tajuria et al., 2017; Weiss et al., 2017), and communication difficulties (Cluley, 2017; Heffron et al., 2018; Tajuria et al., 2017). Other photovoice challenges included camera management (Evans et al., 2016; Genoe & Dupuis, 2014) and difficulties for participants in understanding some concepts of the research itself (Tajuria et al., 2017). The most common strategies to overcome the challenges of photovoice included the use of guided photovoice (Booth & Booth, 2003; Jurkowski & Paul-Ward, 2007), digital cameras instead of disposable cameras (Bossler, 2016; Jurkowski et al., 2009), or asking study-specific questions (Overmars-Marx et al., 2018).

Intellectual Disability and Dementia

While no studies were identified that followed photovoice methodology to explore experiences of dementia in people with intellectual disabilities, a limited number of studies have used other research methods to explore this topic with people who have intellectual disabilities, although the investigations were all conducted by non-disabled researchers. Lloyd et al. (2007) explored the experiences of six participants with Down syndrome and dementia, finding some awareness of aging and changes relating to dementia, with several expressing worries and uncertainty around aspects of getting older, including forgetfulness and confusion. Relationships were viewed as central to the enjoyment of life, including friendships as a main source of companionship and relationships with staff as central to support networks. Wilkinson et al. (2003) conducted four focus groups on topics related to dementia with 31 participants with intellectual disability who did not have dementia. Although participants had a wealth of experience about the changes that can occur when someone develops dementia (in particular confusion, memory loss, physical changes, and aggression), they did not understand how they could help or support their peers. Several participants expressed worry that they themselves would develop dementia. Dementia was particularly associated with the person being “moved away,” with friends often not knowing where the person had gone (Wilkinson et al., 2003).

Research Design and Methodology

Research Questions

Two research questions guided this part of the study encompassing both methodological and conceptual issues, both of which are presented in this article. First, we sought to identify the benefits and challenges of co-researchers with intellectual disability engaging with photovoice methodology. Second, we asked how far this study contributed to the development, and sharing through social action, of new knowledge about dementia in people with intellectual disability.

To address the first question, the process of conducting photovoice was reflected on with co-researchers over a 10-month period of monthly workshops. Conceptually, the second research question was consistent with wider photovoice aims and Freire’s empowerment pedagogy. This was addressed by empowering co-researchers with intellectual disability to visually record areas of strength and concern about dementia, to develop a critical dialogue about dementia through the use of photography, and to facilitate social action and reach policy makers. After group discussion and selecting a choice of preferred images, the co-researchers were subsequently interviewed individually to reflect on their photographs and observations of the interventions, a divergence from a typical photovoice study. This involved asking questions around the content and meaning of the photographs taken. Each was asked what was in the photograph, why it had been taken, what the photograph represented, and what their perceptions were of the observed interventions. Interviews were recorded and transcribed prior to sorting and coding in NVivo.

Photovoice was used by co-researchers with intellectual disability as part of a wider co-produced study implementing psychosocial (non-drug) interventions to participants with a learning disability and dementia (Watchman, 2017). A total of 16 people with intellectual disability and dementia and 22 social care staff were participants in the wider 3-year study which involved a range of data collection methods and is reported elsewhere (Watchman & Mattheys, 2020). This wider study is the largest known to date seeking perspectives of people with intellectual disability and dementia and the first to include photovoice methodology with this population group.

For the photovoice component presented in this article, four of the co-researchers, with permission, visited four study participants with intellectual disability and dementia to observe implementation of a range of psychosocial interventions into dementia care over a 10-month period. The interventions observed were as follows: Playlist for Life see Note 3, talking photo album as a reminiscence activity, cognitive games on a tablet, and design changes in the home in line with “dementia-friendly” design principles—this was a change to lighting to maximize mobility and independence. Following a period of initial training in the methodology and use of a digital camera, the co-researchers observed implementation of the interventions and took photographs of their perceptions of dementia, but not of participants to maintain confidentiality. The three-staged analytical approach saw the selection, contextualization, and coding of image narratives to identify themes.

Those conducting a photovoice study are often referred to as “participants” in research literature; however, we use the term “co-researchers” to acknowledge the role and to distinguish from the wider study participants who were observed and had both intellectual disability and dementia.

Sample

Five co-researchers were recruited into the wider study through a national intellectual disability organization in the United Kingdom. The organization was asked to identify individuals with an intellectual disability who had existing experience of dementia in their peer group and who may be interested in taking part. Researchers selected their roles within the study; for some, this involved becoming a member of the project advisory committee with inclusion from conceptualization before the grant application stage. For another co-researcher, this meant membership of the recruitment panel to select the university-based researcher at the beginning of the project, and others co-produced accessible information to support dissemination. Four of the five co-researchers chose to engage with photovoice methodology with two co-authoring this article. One co-researcher was diagnosed with dementia after photovoice data collection and before his individual interview; he was assessed as retaining capacity, chose to remain in the project, and wished to have the diagnosis disclosed as part of project dissemination. While this inevitably influenced his reflections on dementia, the perceptions of this co-researcher are extremely valid and relevant as will be discussed later.

Analysis

A standard photovoice three-staged approach was taken to analysis: selection of photographs, contextualization (discussion) of photographs, and coding to identify themes or theory (Wang & Burris, 1997). A six-stage process as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006) was followed for coding involving an initial process of familiarization with the data through transcription, multiple readings of the transcripts, photographs, and accompanying labels (the labels were “tags” attached to each photograph and represent the co-researchers’ own descriptions of their photographs). The selected photographs were inserted into the interview transcripts to connect the co-researcher’s stories to their photographs. This stage of analysis also involved open coding and re-coding: searching for themes and producing “thematic maps” of the possible relationships between the data followed by reviewing and defining those themes in consultation with the co-researchers. This was not a linear process as there was a movement back and forward between coding and potential themes until a clear thematic structure was defined.

Ethics

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the appropriate human participants committee with informed consent provided by all participants. Within inclusive research with people who have intellectual disabilities, co-researchers are differentiated from participants by being more actively involved in research (to varying degrees of participation) and working as collaborators involved in the “doing” of the research (Walmsley & Johnson, 2003). Co-researchers in the reported study reflected on their own personal experiences of dementia among peers and of being “experts by experience” (Dorozenko et al., 2016). It is recognized that in participatory research, the lines between researcher and researched can sometimes become blurred (Northway et al., 2015). To ensure that co-researchers were also providing informed consent to take part, a number of steps were taken separate to the process of consent with wider study participants. This included the use of accessible information sheets, additional time given to consider whether to become involved, and the involvement of advocates/support staff if necessary to provide additional support to talk about photovoice. Capacity to understand the study can increase when people are actively taking part in research (Nind, 2008), and the first two photovoice training workshops were designed to further enhance the understanding of this process. Consent was revisited with co-researchers at the end of the training workshops and during the period of photovoice data collection to ensure that each wished to remain in the project. However, the issue of power imbalance was ever-present, particularly in the early stages when there was a reliance on the university-based researcher who had completed photovoice training prior to the study to inform the initial process. While the first two stages of analysis were led by co-researchers with intellectual disability, the use of NVivo and coding of the data proved challenging as part of an inclusive study. This is not uncommon in participatory research, and we followed William’s (2013) guidance by checking back with the co-researchers to ensure as far as possible that the themes in the final stage of analysis were consistent with their perceptions. Regular meetings and the extended workshop and training period supported this process although it is acknowledged that co-researchers did not lead this third part of the analysis.

Findings

Photovoice Process

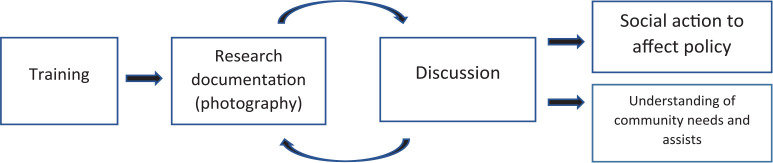

A typical photovoice process, as shown in Figure 2, sees co-researchers engage in training followed by on-going critical discussion involving action–reflection; action being the documenting of issues through photographs and reflection being the critical feedback on the issues arising.

Figure 2.

Photovoice model.

Source: Catalani and Minkler (2009).

To determine the benefits and challenges of photovoice as an appropriate methodology for people with intellectual disabilities when researching experiences of dementia as required by the first research question, co-researchers took part in seven training and information workshops over a 10-month period (see Table 1). As a result of potential difficulties with obtaining informed consent from people being photographed (Cardell, 2015; Tajuria et al., 2017; Weiss et al., 2017), and concerns around confidentiality of the participants with an intellectual disability and dementia who were being visited, an agreed ground rule was that photographs of participants would be excluded from the research. Basic point and shoot digital cameras were introduced, and the co-researchers spent time learning how to use the cameras. A mini printer was provided so that images could be printed out at discussion sessions, providing immediacy and enabling the images to be seen more clearly than by looking at the small screen on the camera, or when transferred to a laptop. This gave further control by enabling co-researcher choice in which images to pick up and discuss, again more tangible than scrolling through a range of images on the laptop.

Table 1.

Structure and Content of Photovoice Training Workshops Over a 10-Month Period.

| No. | Group Workshops | Objective |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Co-researchers learned about the project, set ground rules, and took part in photo-dialogue exercises to start thinking about the meaning behind images. Cameras were provided and exercises completed to practice photography, including “homework” exercises (to take three photographs of something with the co-researchers’ favorite color, or three photographs of things that they liked/were important to them). | To understand the process of photovoice and develop camera skills. |

| 2 | Co-researchers selected, printed, and discussed their chosen photographs from the “homework” exercises. Co-researchers revisited information about the research project and dementia. Consent was revisited. Plans were made to visit participants and psychosocial interventions were discussed. | To learn more about photovoice by printing and talking about photographs and the meaning behind them. To make plans for the fieldwork period. |

| Fieldwork period begins: Co-researchers visited participants to view the psychosocial (non-drug) interventions. Each observed and took photographs to reflect their perspectives. Co-researchers subsequently shared and discussed their chosen photographs and were interviewed by a university researcher. | ||

| 3 | Co-researchers explored other health-based photovoice projects and undertook further camera exercises. | To revisit photovoice methodology |

| 4 | Co-researchers viewed and discussed a range of accessible information and resources to further their understanding of dementia. A group discussion of dementia took place. | To enhance shared understanding of dementia. |

| 5 | Semi-structured interviews which led to individual experiences also being shared. Prompting questions included how dementia had affected people they knew including what changed for the person, how dementia had affected them, and what they felt was important both for the person with dementia and their peers. | To explore co-researcher perception and experiences of dementia and facilitate their development of ideas for photography |

| 6 | Co-researchers translated their thoughts on dementia into ideas for photographs. Co-researchers took more photographs. | Visual representation produced of perceptions of dementia |

| 7 | Co-researchers labeled and discussed their photographs prior to sharing locally and nationally. | To finalize selection of 14 preferred images to present as part of the study |

While all co-researchers took photographs independently, each required variable support with aspects of the process such as prompts around taking photographs and talking about the meanings behind the images taken. A flexible approach was subsequently adopted that involved a guided approach as the university-based researcher or support worker assisted co-researchers during photography. A combination of individual group discussions and semi-structured interviews were used over the period of photovoice data collection.

During training workshops, the co-researchers sometimes forgot the meaning behind their images. Their narratives initially often focused on what was in the photograph and not what the photograph represented. Consequently, the workshop period was extended to provide more time to practice the technique and process. Workshops remained on-going for support, and the methodology was further adapted in the later workshops to include more discussion of dementia, its impact on co-researchers and observed impact on participants, both of which featured in the photographs. Co-researchers reported increased confidence over the 10-month period due to increasing their own knowledge about dementia, and in particular progression of dementia.

Contribution to New Knowledge About Dementia in People With Intellectual Disability

When considering the second research question, three key dementia-related themes were highlighted from thematic analysis of the recorded group sessions and semi-structured interviews: fear about dementia, the importance of friendship, and the need to be involved in future planning.

Fear about dementia

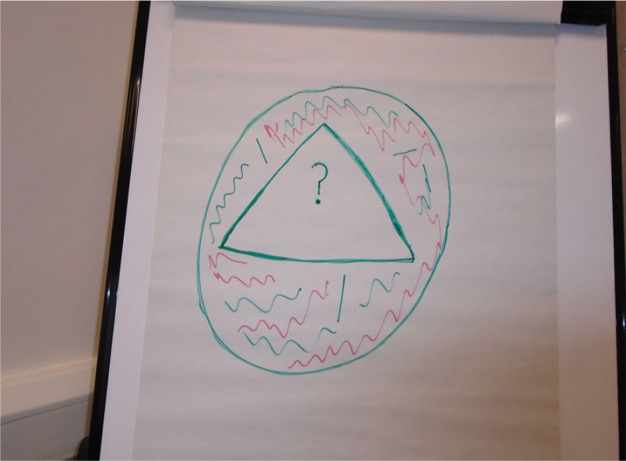

Dementia carried many uncertainties and interrelated fears for the co-researchers as a result of their reflections on the interventions. Advantages of using the psychosocial interventions were reported as helping participants to understand what was happening on a day-to-day basis at a practical level, for example, improved lighting increased confidence in mobility and the playlist reduced agitation, but did not help to explain dementia. One co-researcher captured the sense of observing participants as “lost inside” (Image 1), with the co-researcher reflecting on how people could be lost in a number of different ways:

You would think they are ok, but inside they’re not. Because sometimes I think they get lost inside . . . forget things, forget people . . . I can remember people who got worse dementia, they had to put a gate on the fence because the man kept walking out the door, and if he went out he couldn’t remember to get back.

Image 1.

People with dementia can feel lost in different ways and other people might not know.

Each reflected on their limited prior understanding of dementia before their involvement in the project; however, they had frequently known of a dementia diagnosis among their peers and were aware of several changes that people may experience, including changed behavior and memory loss. All co-researchers expressed uncertainties around changes they had observed as a result of dementia with concepts of the “unknown” most dominant in their conversations around how dementia may progress. Although a number of their peers had developed dementia, the progression of dementia was not something that had been explained, nor was it evident in their observations during the study. This left co-researchers with fears about progression of dementia from both a health and well-being perspective:

The people I knew, there were four people I knew when I was at the center, and they all got dementia. And they’ve all gone now, just disappeared. I don’t know if it was that that killed them, I don’t know. But four people.

The importance of friendship and support

Six of the 14 photographs that the co-researchers selected for further discussion featured aspects of interpersonal relationships and support. This reflected emotional support, group support, friendships, family, and a supportive staff team (Image 2). Based on the observation of the interventions, paid support staff were viewed as integral to positive support both for people with intellectual disabilities and dementia, and their friends. There was a feeling that staff did not always understand the importance of one-to-one interactions that the interventions facilitated, instead viewing this as a task to be completed rather than as enabling the staff member to get to know the person better.

Image 2.

The importance of people supporting each other when things are not good and having people around when they feel down.

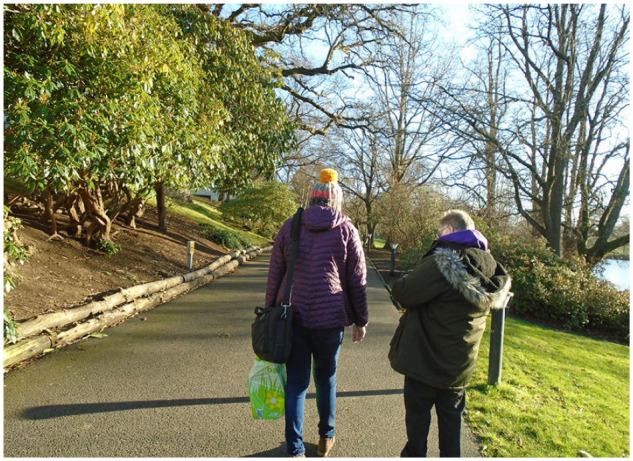

One of the co-researchers shared two photographs that captured aspects of friendship (friends catching up informally over coffee, and friends walking together—Images 3 and 4). The co-researcher spoke of her own concerns for a friend when she was diagnosed with dementia. The diagnosis led to significant changes in the person’s life as she had moved from living alone independently into a generic residential care home for older people. They were prevented from having any contact for a period of time, which had caused a breakdown in their friendship. The co-researcher had recently been invited to renew contact but expressed a number of anxieties around visiting in her new and unfamiliar environment:

I’ve not been to the home . . . One, I’ve been a bit scared, and two, I don’t know what to say . . . I don’t want to go to the home because I don’t know what to say to her about this.

Image 3.

It is important to meet up with friends and catch up.

Image 4.

People look like they are friendly and they are walking together. People need to just keep going.

Strategies for involvement in future planning

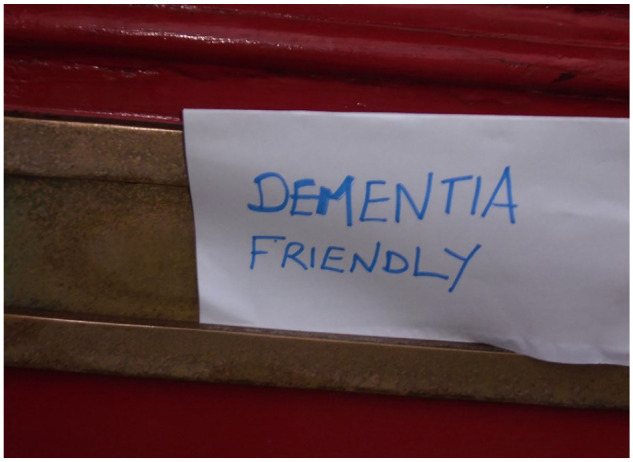

Alongside the importance of the design change as an intervention observed by co-researchers, each reflected on the importance of being involved in planning for future care needs:

I think one of the things that’s important for them to know is to think about what is going to happen in a few months or years and what they need to do to the house—who can help with that?

The photograph, depicting a letterbox with a dementia-friendly sign on it, reflected the importance the co-researcher ascribed to being able to continue to remain at home for as long as possible (Image 5).

Image 5.

People have to keep safe in their own house and to make sure they have people around them.

As interventions were observed, the co-researchers questioned what may happen in the future, raising their own concerns about whether participants would be able to stay in the same accommodation as dementia progressed. Accessible information was perceived as being part of this to help support people with intellectual disabilities both to understand dementia and plan for the future (Image 6).

Image 6.

Easy-to-read resources and easy-to-read information, everything is there for the person to understand. See Note 4.

The co-researcher, who was diagnosed with dementia during the project, reflected on concerns around his own future care needs, the potential of having to change support teams, how his relationship may be sustained with his wife, and the worry around having to go into “institutional care.” He applied observation from photovoice to his own situation and his insistence that he be involved in decisions made about him:

I think one of the things . . . people might be a bit frightened that they might have to go into a long stay hospital, or an institution, if things get really bad . . . I want to stay where I am as long as I can. I don’t want a new team. But I know in the end it’s sometimes . . . That’s the thing that bothers me, I don’t know how long . . . different circumstances might mean having to move . . . It’s like a question mark.

Discussion

Adapting the Process of Photovoice

How the process was adapted is important to understand the benefits and challenges of this methodology. As other authors have noted, digital cameras worked well in the current study (Bossler, 2016; Jurkowski et al., 2009; Jurkowski & Paul-Ward, 2007). Although some of the co-researchers owned personal smartphones, they reflected on the greater accessibility and ease of use of the point and shoot cameras. In addition, the innovative use of a portable photograph printer in the workshops allowed the co-researchers to make instant hard copies of their images that could then be used in their discussions and were perceived as more accessible and more tangible than looking at the images from a computer screen.

We recommend that at least one additional workshop is incorporated before the photography (data collection) stage of the process, to enable co-researchers to explore their thoughts on the subject area and generate ideas for how they may capture those thoughts on camera. Other authors have suggested that a preparatory interview may be of benefit (Akkerman et al., 2014), and indeed Wang and Burris (1997) also noted that “brainstorming ideas” sessions may be useful. Conversely, we found that conducting semi-structured interviews much later in the data collection period was a way to reinforce the meaning behind the images taken and selected. In addition, co-researchers reported that the extended workshop period contributed to their increased confidence prior to taking photographs and crucial to their continued involvement in the study, and it allowed for a relationship to be developed with the university-based researcher.

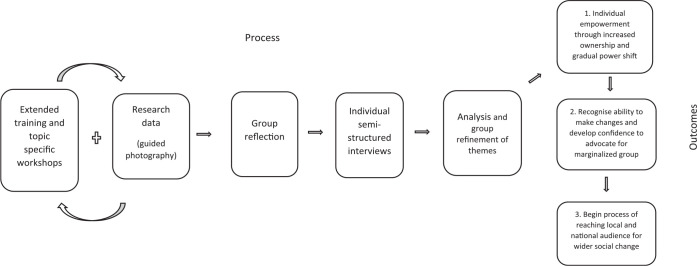

All of the co-researchers required some level of additional support to engage with the photovoice methodology, and the guided approach (Overmars-Marx et al., 2018) supported this. The addition of topic-specific “discussion of dementia” sections to the workshops led to greater understanding of the changes experienced by participants. This meant that the workshops were more effective in the later stages of the project, as co-researchers became more knowledgeable about dementia and the interventions and had visited participants more than once. Figure 3 reflects the amendments we made to the photovoice process and subsequent outcomes in the study. We recognize that this study reflected views of people with intellectual disability, and that the process and outcomes should not be assumed to be the same for other marginalized groups although this is worthy of further investigation.

Figure 3.

Intellectual disability and dementia, revised photovoice model.

Source: Watchman, Mattheys, Doyle, Boustead, Boustead & Ricones, 2020.

Developing Knowledge of Dementia Among a Marginalized Group

The second research question was to understand how far this study contributes to new knowledge about dementia and associated social action among people with intellectual disability. This has been demonstrated by co-researchers reflecting positive observations of the interventions. However, this was alongside concern about their sustainability if staff did not commit to them or recognize their value, and fear of appropriate support and housing for peers as dementia progressed. Internationally, the history of intellectual disability services is one of institutionalization (Johnson & Traustadottir, 2005). In Scotland, the main long-stay hospital closure period ended in 2005 (Scottish Consortium for Learning Disabilities, 2014). As such, a number of older people with intellectual disabilities will either have spent many years themselves living in institutional care or have peers who lived through this period of segregation. It is in this social and historical context that the potential loss of independence emerged as a key concern, particularly for the co-researcher who had been diagnosed with dementia. Having seen peers “disappear” after a progression of dementia, concerns were expressed around the potential loss of current support, being moved away from home, and where they were moved to. This is consistent with published research highlighting fear of friends “disappearing” (Wilkinson et al., 2003) and concern about effects of aging (Lloyd et al., 2007). New findings included co-researcher’s reflection on their own perceptions of dementia including impact on personal and spousal relationships and the fear of a return to institutional care.

The process of photovoice is intended to enable marginalized groups to increase their understanding in a specific area, in this case dementia, and to share this at local, national, and international levels. Indeed, Freire (1970) maintained that the collective process of reflection and discussion of images was essential to uncover constructs that exacerbate marginalization. Critical consciousness would only be achieved when those engaging with photovoice moved beyond an individual level of empowerment. This begins with group work in the photovoice process and is further developed when knowledge is shared with communities. Wang and Burris (1997) extended this with a belief that photovoice is successful if it encourages engagement with power brokers to facilitate social change.

In this study, at an individual level, a key outcome for co-researchers was that the project led to their enhanced knowledge and critical awareness of dementia in people with intellectual disabilities. Each developed practical experience of the application of psychosocial interventions and demonstrated meaningful insight into their perceptions of dementia through individual and group discussion. As evidenced in earlier photovoice research (Dorozenko et al., 2016), research roles and relationships of power shifted throughout the process: at the beginning of the process in line with Freire’s magical level, the project was very much led by the university researchers who provided training, but as the project developed, the co-researchers took greater ownership over aspects of the research such as control over the photography process, choosing which photographs to take, which to take forward and share within the project, how these were labeled, and how and where to disseminate.

Consistent with Freire’s empowerment education, co-researchers became aware of their responsibility for choices that either maintained or changed the reality they had observed. After observing interventions and reflecting on images, each recognized what contributed to participants’ living well with dementia and actively sought out further dementia training, requesting an additional workshop to increase their knowledge of dementia moving through the “magical” level. As part of reflecting on their own experiences, co-researchers then began to advocate strongly for the needs of people with intellectual disabilities to be involved in future planning about the decisions which would affect them, for example, identifying a need to take steps to ensure that people could stay in their own homes as long as possible after a diagnosis of dementia.

By providing critical feedback on availability of accessible resources and information to talk about dementia to people with intellectual disability, co-researchers demonstrated further activity at the level of critical consciousness. At the end of the study in 2019, two co-researchers had already taken forward their learning into their local community by sharing knowledge with their peers through delivery of dementia training within their intellectual disability self-advocacy networks. This was continued through an end-of-project conference for people with intellectual disability, which featured presentations from co-researchers and a photographic display of the images from photovoice. In addition, two co-researchers selected images and wrote content before delivering both oral and poster presentations at an international intellectual disability conference. Both engaged with conference delegates to talk about the project and explain their choice of images on the poster resulting in feedback on social media praising “participatory methods with planned social action to maximize outcomes” and “More of this approach please,” affirming their increased knowledge, confidence, and ownership of the images. While all co-authors of this article took on different roles, two co-researchers with intellectual disability contributed to the findings section by selecting images to include and associated captions (Evans-Agnew & Rosemberg, 2016).

Although the project demonstrated individual- and societal-level impacts at both local and national levels as noted by Freire (1970), this has not yet extended to wider macro level, or influence over policy makers as required by Wang and Burris (1997). This has proved beyond the scope of the project, and while the underpinning goals of photovoice include under-represented communities being empowered to reach out to policy makers and effect social change (Wang and Burris, 1997), there are questions around whether this can be achieved under the constraints of a funded project. While other photovoice projects have reported similar barriers in facilitating change, and a need for on-going collaboration to drive forward social action (Walton et al., 2012), this does not mean that social change cannot be achieved. We suggest that reach may be at local, national, or international level, but that it may not necessarily have to relate to policy to have wider reach or effect change.

The diagnosis of dementia in a co-researcher during the study could not have been anticipated and support remains in place for this individual both locally and from the university. It is his desire that he continues to advocate from, and write about, the perspective of his lived experience in the way that others in the field of dementia without an intellectual disability have done, see, for example, the work of the European Working Group of People with Dementia, Scottish Dementia Working Group, and Dementia Australia Advisory Committee. In doing so, his intention is to lead the way for others recognizing the lack of a voice among people with an intellectual disability and dementia and their partners. Photovoice methodology itself has been demonstrated to offer potential beyond its limited use to date with this population.

Summary

Photovoice was implemented within a participatory action framework that facilitated group and individual reflection on the perceptions of dementia and subsequently led to social action by co-researchers with intellectual disability at local and national level. As the first paper offering original insight into experiences of photovoice methodology with this marginalized group, contribution has been made to the existing, albeit limited, international literature on this approach with people with dementia and people with intellectual disability. Authority has been given to people with intellectual disability as co-researchers beyond the training and data collection stages. Benefits were observed as co-researchers demonstrated individual- and community-level empowerment, achieving critical consciousness, based on Freire’s critical pedagogy rather than Wang and Burris’ subsequent requirement for wider policy change. However, use of photovoice itself does not guarantee inclusion, nor does it necessarily equate to empowerment. The study identified challenges that required process adaptation, including an extended workshop period and time to develop relationships within the research team. New insight into fear of dementia and impact on future support, relationships, and housing have been identified that require addressing in practice and future research. Empowerment should be viewed as both a process and an outcome, enabling co-researchers to understand and demonstrate changes through individual- and community-based action initially. Long-term action is required for a policy shift to occur which highlights a limitation of funded studies where resources are required on an on-going basis to support meaningful long-term engagement with wider reach.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_file_1_Scoping_review for Revisiting Photovoice: Perceptions of Dementia Among Researchers With Intellectual Disability by Karen Watchman, Kate Mattheys, Andrew Doyle, Louise Boustead and Orlando Rincones in Qualitative Health Research

Author Biographies

Karen Watchman is a Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Health Sciences and Sport, University of Stirling, Scotland.

Kate Mattheys is an Independent Advocate at Adapt North East, England.

Andrew Doyle is an advocate for people with intellectual disabilities, Scotland.

Louise Boustead is an advocate for people with intellectual disabilities, Scotland.

Orlando Rincones is a research assistant at the Centre for Oncology Education and Research Translation (CONCERT), Ingham Institute for Applied Medical Research & University of New South Wales, Australia.

The term “disabled people” is typically used in the context of people with a physical disability. This is generally the preferred term of individuals who follow the social model of disability and maintain that “disability” is caused by barriers put in place by society. The term “person with” an intellectual disability is used throughout this article as it is the preferred terminology of this population reflecting a person-centered approach.

The following electronic databases were searched: CINAHL, Health Source, MEDLINE, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, SocINDEX, and Scopus, where the title or abstract included photovoice, dementia, “learning disabilit,” “intellectual disabilit,” Alzheimer, and “down syndrome,” reflecting terminology in and outside the United Kingdom. Data were saved using EndNote management software. The PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) was followed to summarize by background, objectives, eligibility criteria, methods, results, and conclusions as related to the research questions (Tricco et al., 2018). Forty-six articles were identified through abstracts reduced to 39 after duplications were removed, although articles were included if developed for a thesis and reported on different elements of the same study. A further 10 were removed after full-text review as shown in Figure 1. The remaining 29 articles consisted of six that included people with dementia from four countries and 23 including people with intellectual disability from five countries, with none that combined the two, further demonstrating the importance of this study. Over half of the existing studies were conducted in the United States or Canada, with a smaller number in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Australia and none beyond high-income countries in the Global North.

“Playlist for Life” is a Scottish charity founded in 2013, striving to explore someone’s life story through a personal playlist that gathers the tunes attached to memories and emotions: https://www.playlistforlife.org.uk/

Image 6 depicts Jenny’s Diary—a resource to support conversations about dementia with people who have an intellectual disability (Watchman et al., 2015).

Footnotes

Author’s Note: Kate Mattheys is now an Independent Advocate at Adapt North East, England. Andrew Doyle and Louise Boustead are affiliated with Key, Dumfries, Scotland. Both have an intellectual disability and contributed as co-researchers on a funded project. Orlando Rincones contributed to the study as a Postgraduate Student, Masters in Health Research, University of Stirling, Scotland.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval for this research was granted for “Life through a Lens” study by the University of Stirling’s NHS, Invasive or Clinical Research Committee (NICR; 16/17–52).

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by Alzheimer’s Society Implementation (grant no. 292).

ORCID iDs: Karen Watchman  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0000-3589

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0000-3589

Orlando Rincones  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9727-7871

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9727-7871

Supplemental Material: Supplemental Material for this article is available online at journals.sagepub.com/home/qhr. Please enter the article’s DOI, located at the top right hand corner of this article in the search bar, and click on the file folder icon to view.

References

- Akkerman A., Janssen C. G. C., Kef S., Meininger H. P. (2014). Perspectives of employees with intellectual disabilities on themes relevant to their job satisfaction: An explorative study using photovoice. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27(6), 542–554. 10.1111/jar.12092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge J. (2007). Picture this: The use of participatory photographic research methods with people with learning disabilities. Disability & Society, 22(1), 1–17. 10.1080/09687590601056006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2007). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ataie J. E. (2014). “Who would have thought, with a diagnosis like this, I would be happy?”: Portraits of perceived strengths and resources in early-stage dementia [Doctoral thesis, Portland State University; ]. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds/1107 [Google Scholar]

- Baker T. A., Wang C. C. (2006). Photovoice: Use of a participatory action research method to explore the chronic pain experience in older adults. Qualitative Health Research, 16(10), 1405–1413. 10.1177/1049732306294118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigby C., Frawley P. (2010). Reflections on doing inclusive research in the “making life good in the community” study. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 35(2), 53–61. 10.3109/13668251003716425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth T., Booth W. (2003). In the frame: Photovoice and mothers with learning difficulties. Disability & Society, 18(4), 431–442. 10.1080/0968759032000080986 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bossler A. M. (2016). Exploring the process and potential of photovoice with culturally and linguistically diverse adults with intellectual/developmental disabilities [Doctoral thesis, University of Hawaii; ]. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Exploring-the-process-and-potential-of-Photovoice-Bossler/0d32e935af01699733efc36e24cf28760ad94a5e [Google Scholar]

- Brake L. R., Schleien S. J., Miller K. D., Walton G. (2012). Photovoice: A tour through the camera lens of self-advocates. Social Advocacy & Systems Change, 3, 44–53. http://sites.cortland.edu/sasc/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2012/10/Brake_etal_Photovoice.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardell B. (2015). Reframing health promotion for people with intellectual disabilities. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 2, 1–11. 10.1177/2333393615580305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalani C., Minkler M. (2009). Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Education & Behavior, 37(3), 424–451. 10.1177/1090198109342084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluley V. (2017). Using photovoice to include people with profound and multiple learning disabilities in inclusive research. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45(1), 39–46. 10.1111/bld.12174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorozenko K. P., Bishop B. J., Roberts L. D. (2016). Fumblings and faux pas: Reflections on attempting to engage in participatory research with people with an intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 41(3), 197–208. 10.3109/13668250.2016.1175551 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorozenko K. P., Roberts L. D., Bishop B. (2015). The identities and social roles of people with an intellectual disability: Challenging dominant cultural worldviews, values and mythologies. Disability & Society, 30(9), 1345–1364. 10.1080/09687599.2015.1093461 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dowse L. (2009). “It’s like being in a zoo”: Researching with people with intellectual disability. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 9(3), 141–153. 10.1111/j.1471-3802.2009.01131.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D., Robertson J., Candy A. (2016). Use of photovoice with people with younger onset dementia. Dementia, 15, 798–813. 10.1177/1471301214539955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Agnew R. A., Rosemberg M.-A. S. (2016). Ques-tioning photovoice research: Whose voice? Qualitative Health Research, 26(8), 1019–1030. 10.1177/1049732315624223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. (2014). Pedagogy of the oppressed: 30th Anniversary Edition. 3rd ed. Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Genoe M. R., Dupuis S. L. (2014). The role of leisure within the dementia context. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 13(1), 33–58. 10.1177/1471301212447028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra S. R., Rodriguez S. P., Demain S., Figueiredo D. M., Sousa L. X. (2013). Evaluating pro families-dementia: Adopting photovoice to capture clinical significance. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 12(5), 569–587. 10.1177/1471301212437779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper D. (2012). Visual sociology. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Heffron J. L., Spassiani N. A., Angell A. M., Hammel J. (2018). Using photovoice as a participatory method to identify and strategize community participation with people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 25(5), 382–395. 10.1080/11038128.2018.1502350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hithersay R., Startin C. M., Hamburg S., Mok K. Y., Hardy J., Fisher E., Strydom A. (2019). Association of dementia with mortality among adults with Down syndrome older than 35 years. Journal of the American Medical Association Neurology, 76(2), 152–160. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.3616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K., Traustadottir R. (Eds.) (2005). Deinstitutional-ization and people with intellectual disabilities: In and out of institutions. Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Jurkowski J. M., Paul-Ward A. (2007). Photovoice with vulnerable populations: Addressing disparities in health promotion among people with intellectual disabilities. Health Promotion Practice, 8(4), 358–365. 10.1177/1524839906292181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkowski J. M., Rivera Y., Hammel J. (2009). Health perceptions of Latinos with intellectual disabilities: The results of a qualitative pilot study. Health Promotion Practice, 10(1), 144–155. 10.1177/1524839907309045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd V., Kalsy S., Gatherer A. (2007). The subjective experience of individuals with Down syndrome living with dementia. Dementia, 6(1), 63–88. 10.1177/1471301207075633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCarron M., McCallion P., Reilly E., Mulryan N. (2014). A prospective 14-year longitudinal follow-up of dementia in persons with Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58(1), 61–70. 10.1111/jir.12074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nind M. (2008). Conducting qualitative research with people with learning, communication and other disabilities: Methodological challenges. http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/491/1/MethodsReviewPaperNCRM-012.pdf

- Northway R., Howarth J., Evans L. (2015). Participatory research, people with intellectual disabilities and ethical approval: Making reasonable adjustments to enable participation. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(3–4), 573–581. 10.1111/jocn.12702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver M. (1992). Changing the social relations of research production? Disability, Handicap & Society, 7(2), 101–114. 10.1080/02674649266780141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Overmars-Marx T., Thomése F., Moonen X. (2018). Photovoice in research involving people with intellectual disabilities: A guided photovoice approach as an alternative. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(1), e92–104. 10.1111/jar.12329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povee K., Bishop B. J., Roberts L. D. (2014). The use of photovoice with people with intellectual disabilities: Reflections, challenges and opportunities. Disability & Society, 29(6), 893–907. 10.1080/09687599.2013.874331 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M., Knapp M., Guerchet M., McCrone P., Prina M., Comas-Herrera A., Salimkumar D. (2014). Dementia UK: Overview (2nd ed.). http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/59437/1/Dementia_UK_Second_edition_-_Overview.pdf

- Schwartz A. E., Kramer J. M., Cohn E. S., McDonald K. E. (2019). “That felt like real engagement”: Fostering and maintaining inclusive research collaborations with individuals with intellectual disability. Qualitative Health Research, 30(2), 236–249. 10.1177/1049732319869620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Consortium for Learning Disabilities. (2014). The National Confidential Forum: Estimating the number of people with learning disabilities placed in institutional care as children, 1930 – 2005. https://www.scld.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/ncf_report.pdf

- Tajuria G., Read S., Priest H. M. (2017). Using photovoice as a method to engage bereaved adults with intellectual disabilities in research: Listening, learning and developing good practice principles. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities, 11(5–6), 196–206. 10.1108/AMHID-11-2016-0033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco A. C., Lillie E., Zarin W., O’Brien K., Colquhoun H., Levac D., Straus S. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley J., Johnson K. (2003). Inclusive research with people with learning disabilities: Past, present and futures. Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Walton G., Schleien S. J., Brake L. R., Trovato C. C., Oakes T. (2012). Photovoice: A collaborative methodology giving voice to underserved populations seeking community inclusion. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 46(3), 168–178. https://js.sagamorepub.com/trj/article/view/2797 [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Burris M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health, Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369–387. 10.1177/109019819702400309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watchman K. (2017). Life through a lens. https://www.stir.ac.uk/about/faculties/health-sciences-sport/research/research-groups/enhancing-self-care/life-through-a-lens/

- Watchman K., Janicki M. (2019). The intersection of intellectual disability and dementia: Report of the international summit on intellectual disability and dementia. The Gerontologist, 59(3), 411–419. 10.1093/geront/gnx160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watchman K., Mattheys K. (2020). Dementia care for persons ageing with intellectual disability—Developing non-pharmacological strategies for support. In Putnam M., Bigby C. (Eds.), Handbook on aging with disability. Taylor & Francis/Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Watchman K., Tuffrey-Wijne I., Quinn S. (2015). Jenny’s diary: Supporting conversations about dementia with people who have a learning disability. Pavilion; http://www.learningdisabilityanddementia.org/jennys-diary.html [Google Scholar]

- Weiss J. A., Burnham Riosa P., Robinson S., Ryan S., Tint A., Viecili M., . . . Shine R. (2017). Understanding special Olympics experiences from the athlete perspectives using photo-elicitation: A qualitative study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 30(5), 936–945. 10.1111/jar.12287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson H., Kerr D., Rae C. (2003). People with a learning disability: Their concerns about dementia. Journal of Dementia Care, 11(1), 27–29. https://careinfo.org/?s=People+with+a+learning+disability%3A+their+concerns+about+dementia.+&post_type=jdc-archive [Google Scholar]

- Williams V. (2013). Learning disability and practice. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2019). Disability inclusion. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/disability

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplementary_file_1_Scoping_review for Revisiting Photovoice: Perceptions of Dementia Among Researchers With Intellectual Disability by Karen Watchman, Kate Mattheys, Andrew Doyle, Louise Boustead and Orlando Rincones in Qualitative Health Research