Abstract

Recent studies indicate that many developing tissues modify glycolysis to favor lactate synthesis (Agathocleous et al., 2012; Bulusu et al., 2017; Gu et al., 2016; Oginuma et al., 2017; Sá et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2016), but how this promotes development is unclear. Using forward and reverse genetics in zebrafish, we show that disrupting the glycolytic gene phosphoglycerate kinase-1 (pgk1) impairs Fgf-dependent development of hair cells and neurons in the otic vesicle and other neurons in the CNS/PNS. Fgf-MAPK signaling underperforms in pgk1- / - mutants even when Fgf is transiently overexpressed. Wild-type embryos treated with drugs that block synthesis or secretion of lactate mimic the pgk1- / - phenotype, whereas pgk1- / - mutants are rescued by treatment with exogenous lactate. Lactate treatment of wild-type embryos elevates expression of Etv5b/Erm even when Fgf signaling is blocked. However, lactate’s ability to stimulate neurogenesis is reversed by blocking MAPK. Thus, lactate raises basal levels of MAPK and Etv5b (a critical effector of the Fgf pathway), rendering cells more responsive to dynamic changes in Fgf signaling required by many developing tissues.

Research organism: Zebrafish

Introduction

Development of the paired sensory organs of the head relies on critical contributions from cranial placodes. Of the cranial placodes, the developmental complexity of the otic placode is especially remarkable for producing the entire inner ear, with its convoluted epithelial labyrinth and rich cell type diversity. The otic placode initially forms a fluid filled cyst, the otic vesicle, which subsequently undergoes extensive proliferation and morphogenesis to produce a series of interconnected chambers containing sensory epithelia (Whitfield, 2015). Sensory epithelia comprise a salt-and-pepper pattern of sensory hair cells and support cells. Hair cell specification is initiated by expression of the bHLH factor Atonal Homolog 1 (Atoh1) (Bermingham et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2002; Millimaki et al., 2007; Raft et al., 2007; Woods et al., 2004). Atoh1 subsequently activates expression of Notch ligands that mediate specification of support cells via lateral inhibition. Hair cells are innervated by neurons of the statoacoustic ganglion (SAG), progenitors of which also originate from the otic vesicle. Specification of SAG neuroblasts is initiated by localized expression of the bHLH factor Neurogenin1 (Ngn1) (Andermann et al., 2002; Korzh et al., 1998; Ma et al., 1998; Raft et al., 2007). A subset of SAG neuroblasts delaminate from the otic vesicle to form ‘transit-amplifying’ progenitors that slowly cycle as they migrate to a position between the otic vesicle and hindbrain before completing differentiation and extending processes to hair cells and central targets in the brain (Alsina et al., 2004; Kantarci et al., 2016; Vemaraju et al., 2012).

Development of both neurogenic and sensory domains of the inner ear requires dynamic regulation of Fgf signaling. Fgf-dependent induction of Ngn1 establishes the neurogenic domain during placodal stages, marking one of the earliest molecular asymmetries in the otic placode in chick and mouse embryos (Abelló et al., 2010; Alsina et al., 2004; Magariños et al., 2010; Mansour et al., 1993; Pirvola et al., 2000). Subsequently, as neurogenesis subsides, Fgf also specifies sensory domains of Atoh1 expression (Hayashi et al., 2008; Ono et al., 2014; Pirvola et al., 2002). Moreover, in the mammalian cochlea different Fgf ligand-receptor combinations fine-tune the balance of hair cells and support cells (Hayashi et al., 2007; Jacques et al., 2007; Mansour et al., 2009; Pirvola et al., 2000; Puligilla et al., 2007; Shim et al., 2005). In zebrafish, sensory domains form precociously during the earliest stages of otic induction in response to Fgf from the hindbrain and subjacent mesoderm (Gou et al., 2018; Millimaki et al., 2007). Ongoing Fgf later specifies the neurogenic domain in an abutting domain of the otic vesicle (Kantarci et al., 2015; Vemaraju et al., 2012). As otic development proceeds, the overall level of Fgf signaling increases, reflected by increasing expression of numerous genes in the Fgf synexpression group, including transcriptional effectors Etv4 (Pea3) and Etv5b (Erm), and the feedback inhibitor Spry (Sprouty1, 2 and 4). Sensory epithelia gradually expand during development and express Fgf, contributing to the general rise in Fgf signaling. Similarly, mature SAG neurons express Fgf5. As more neurons accumulate, rising levels of Fgf eventually exceed an upper threshold to terminate further specification of neuroblasts and delay differentiation of transit-amplifying SAG progenitors (Vemaraju et al., 2012). Additionally, elevated Fgf inhibits further hair cell specification while maintaining support cells in a quiescent state (Bermingham-McDonogh et al., 2001; Jiang et al., 2014; Ku et al., 2014; Maier and Whitfield, 2014). Thus, dynamic changes in Fgf signaling regulate the onset, amount, and pace of neural and sensory development in the inner ear.

There is increasing evidence that dynamic regulation of glycolytic metabolism is critical for proper development of various tissues. For example, populations of proliferating stem cells or progenitors, including human embryonic stem cells, neural stem cells, hematopoietic stem cells, and posterior presomitic mesoderm, modify glycolysis by shunting pyruvate away from mitochondrial respiration in favor of lactate synthesis, despite an abundance of free oxygen (Agathocleous et al., 2012; Bulusu et al., 2017; Gu et al., 2016; Oginuma et al., 2017; Sá et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2016). This is similar to ‘aerobic glycolysis’ (also known as the ‘Warburg Effect’) exhibited by metastatic tumors, thought to be an adaptation for accelerating ATP synthesis while simultaneously producing carbon chains needed for rapid biosynthesis (Liberti and Locasale, 2016). In addition, aerobic glycolysis and lactate synthesis appears to facilitate cell signaling required for normal development. For example, aerobic glycolysis promotes relevant cell signaling to stimulate differentiation of osteoblasts, myocardial cells, and fast twitch muscle (Esen et al., 2013; Menendez-Montes et al., 2016; Ozbudak et al., 2010; Tixier et al., 2013), as well as maintenance of cone cells in the retina (Aït-Ali et al., 2015).

In a screen to identify novel regulators of SAG development in zebrafish, we recovered two independent mutations that disrupt the glycolytic enzyme Phosphoglycerate Kinase 1 (Pgk1). Loss of Pgk1 causes a delay in upregulation of Fgf signaling in the otic vesicle, causing a deficiency in early neural and sensory development. We show that Pgk1 is co-expressed with Fgf ligands in the otic vesicle, as well as in the olfactory epithelium and various clusters of neurons in cranial ganglia and the neural tube. Moreover, Pgk1 acts non-autonomously to promote Fgf signaling at a distance by promoting synthesis and secretion of lactate. Lactate independently activates the MAPK pathway, leading to elevated expression of the effector Etv5b, priming the pathway to render cells more responsive to dynamic changes in Fgf levels.

Results

Initial characterization of sagd1

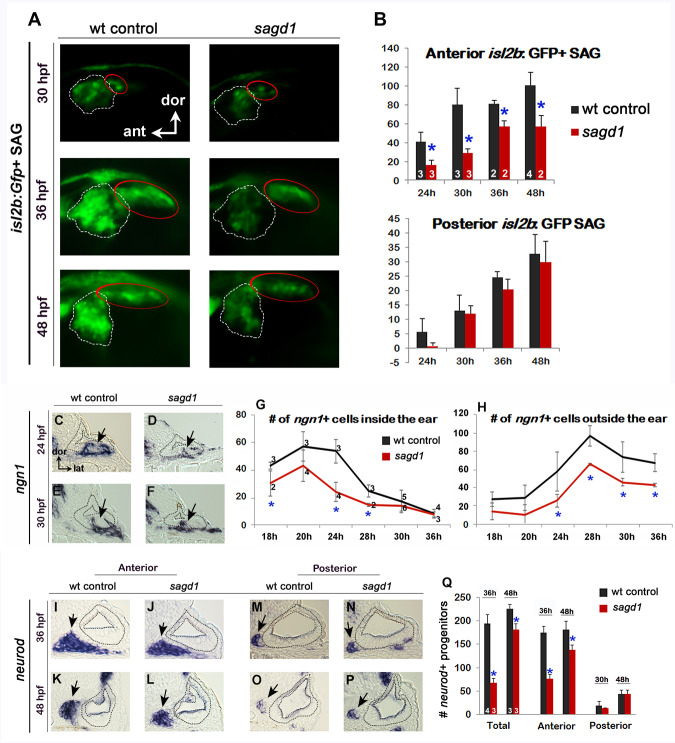

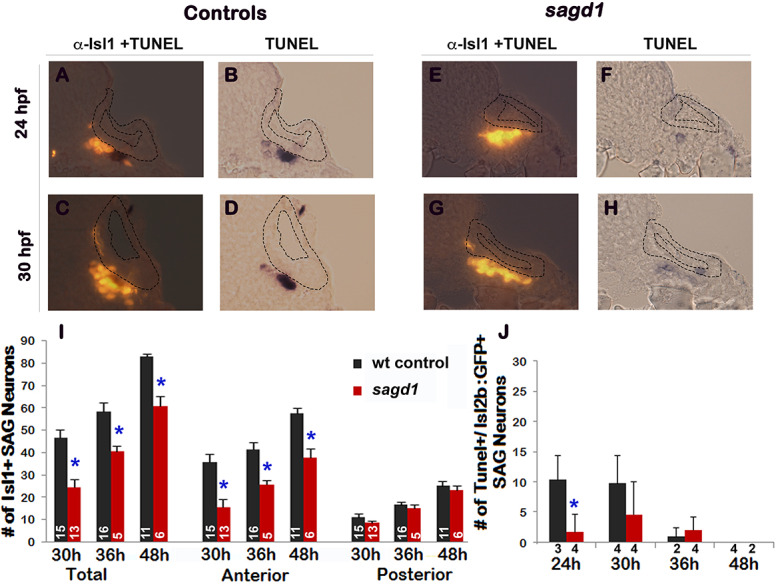

To identify novel genes required for SAG development, we conducted an ENU mutagenesis screen for mutations that specifically alter the number or distribution of post-mitotic isl2b:Gfp+ SAG neurons. A recessive lethal mutation termed sagd1 (SAG deficient1) was recovered based on a deficiency in the anterior/vestibular portion of ganglion, which are the first SAG neurons to form. Quantification of isl2b:Gfp+ cells in serial sections of sagd1- / - mutants revealed a ~ 60% deficiency in anterior SAG neurons (which are essential for vestibular function) at 24 and 30 hpf (Figure 1A,B). The number of anterior neurons remained lower than normal through at least 48 hpf whereas accumulation of posterior SAG neurons (which includes auditory neurons) appeared normal (Figure 1B). Staining with anti-Isl1/2 antibody, which labels a more mature subset of SAG neurons, showed a similar trend: There was a 60% deficiency in anterior neurons from the earliest stages of SAG development whereas subsequent formation of posterior neurons was normal (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A–I). Of note, the early deficit of SAG neurons did not result from increased apoptosis (Figure 1—figure supplement 1J), and in fact sagd1- / - mutants produced fewer apoptotic cells than normal. sagd1- / - mutants show no overt defects in gross morphology, although sagd1- / - mutants do show deficits in balance and motor coordination indicative of vestibular dysfunction. Mutants typically die by 10–12 dpf.

Figure 1. Initial analysis of sagd1.

(A) Lateral views of isl2b:Gfp+ SAG neurons in live wild-type (wt) embryos and sagd1 mutants at the indicated times. The anterior/vestibular portion of the SAG (outlined in white) is deficient in sagd1 mutants, whereas the posterior SAG (outlined in red) appears normal. (B) Number (mean and s.d.) of isl2b:Gfp+ anterior neurons and posterior neurons in wild-type and sagd1 embryos at the times indicated. Sample sizes are indicated. Asterisks, here and in subsequent figures, indicate significant differences (p<0.05) from wild-type controls. (C–F) Cross-sections through the anterior/vestibular portion of the otic vesicle (outlined) showing expression of ngn1 in wild-type embryos and sagd1 mutants at 24 and 30 hpf. (G, H) Mean and standard deviation of ngn1+ cells in the floor of the otic vesicle (G) and in recently delaminated SAG neuroblasts outside the otic vesicle (H), as counted from serial sections. (I–P) Cross-sections through the anterior/vestibular and posterior/auditory regions of the otic vesicle showing expression of neurod in transit-amplifying SAG neuroblasts at 36 and 48 hpf. (Q) Mean and standard deviation of neurod+ SAG neuroblasts at 30 and 48 hpf counted from serial sections. Sample sizes are indicated (B, G, Q).

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Quantitation of mature Isl1/2+ SAG neurons and TUNEL in sagd1 mutants.

To further characterize the sagd1- / - phenotype, we examined earlier stages of SAG development. Specification of SAG neuroblasts is marked by expression of ngn1 in the floor of the otic vesicle, a process that normally begins at 16 hpf, peaks at 24 hpf, and then gradually declines and ceases by 42 hpf (Vemaraju et al., 2012). We observed that early stages of neuroblast specification were significantly impaired in sagd1- / - mutants, with only 30% of the normal number of ngn1+ neuroblasts inside the otic vesicle at 24 hpf (Figure 1C,D,G). However, subsequent stages of neural specification gradually improved in sagd1- / - mutants, such that the number of ngn1+ neuroblasts in the otic vesicle was normal by 30 hpf (Figure 1E,F,G). In the next stage of SAG development, a subset of SAG neuroblasts delaminates from the otic vesicle and enters a transit-amplifying phase. Recently delaminated neuroblasts continue to express ngn1 for a short time before shifting to expression of neurod, which is then maintained until SAG progenitors mature into post-mitotic neurons. In sagd1- / - mutants, the number of ngn1+ neuroblasts outside the otic vesicle was reduced by 50–60% at every stage examined (Figure 1H). Similarly, the number of neurod+ transit-amplifying cells was strongly reduced in sagd1- / - mutants (Figure 1I–Q). This deficit was more pronounced at 30 hpf (~60% decrease) than at 48 hpf (~20% decrease). Moreover, deficit was restricted to anterior transit-amplifying cells that give rise to anterior neurons, which are the first to form, whereas accumulation of later-forming posterior progenitors was normal (Figure 1Q). In summary, the neural deficit observed in sagd1- / - mutants reflects a deficiency in specification of early neuroblasts that normally form the anterior SAG, which is essential for vestibular function. In addition, the continuing deficit in anterior transit-amplifying cells at later stages likely contributes to a long-term deficit in anterior SAG neurons.

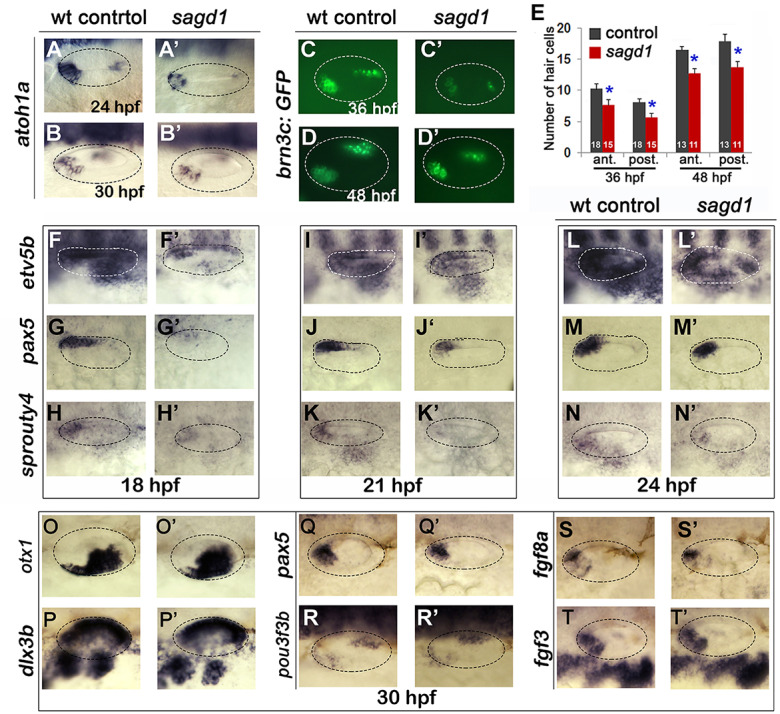

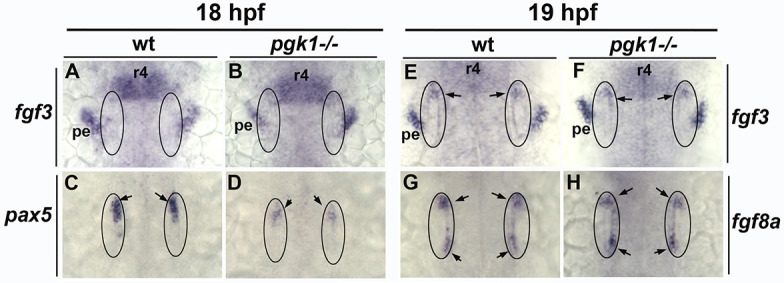

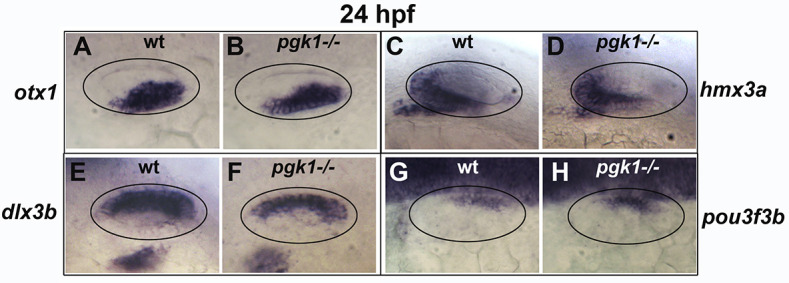

We next examined other aspects of otic development in sagd1- / - mutants. Expression of prosensory marker atoh1a was reduced in both anterior (utricular) and posterior (saccular) maculae at 24 and 30 hpf (Figure 2A–B’). In agreement, sagd1- / - mutants produced roughly 25% fewer than normal hair cells in the utricle and saccule at 36 and 48 hpf (Figure 2C–E). Because development of SAG progenitors and sensory epithelia both rely on Fgf signaling, we also examined expression of various Fgf ligands and downstream Fgf-target genes. Expression of fgf3 and fgf8a appeared relatively normal in sagd1- / - mutants from 18 to 30 hpf (Figure 2S–T’, and data not shown). However, expression of downstream Fgf-targets etv5b, pax5 and sprouty4 were severely deficient in the otic vesicle of sagd1- / - mutants at 18 hpf (Figure 2F–H’). Expression of these genes partially recovered by 21 hpf and was only mildly reduced by 24 hpf (Figure 2I–N’). Despite these changes, markers of axial identity were largely unaffected at 30 hpf, including the dorsal marker dlx3b, the ventrolateral marker otx1, the anteromedial marker pax5 and posteromedial marker pou3f3b (Figure 2O–R’). These data suggest that Fgf signaling is impaired during early stages of otic vesicle development but slowly improves during later stages, which could explain the early deficits in sensory and neural specification. However, recovery of Fgf signaling is apparently incomplete or insufficient since production of new hair cells in sagd1 mutants continues at a reduced rate through at least 48 hpf.

Figure 2. Sensory development and early Fgf signaling are impaired in sagd1 mutants.

(A–D”, F–T’) Dorsolateral views of whole mount specimens (anterior to the left) showing expression of the indicated genes in the otic vesicle (outlined) at the indicated times in wild-type embryos and sagd1 mutants. (E) Mean and standard deviation of hair cells in the anterior/utricular and posterior/auditory maculae at 36 and 48 hpf in wild-type embryos (black) and sagd1 mutants (red). Sample sizes are indicated.

Identification of the sagd1 locus: A novel role for Pgk1

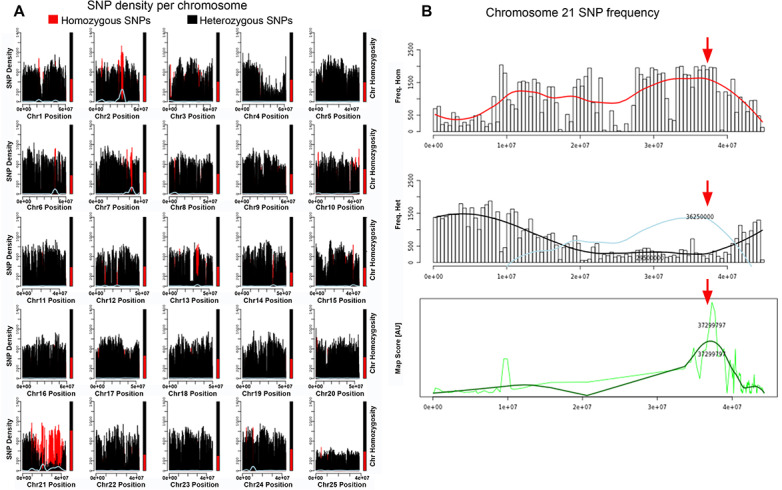

To identify the affected locus in sagd1- / - mutants, we used whole genome sequencing and homozygosity mapping approaches (Obholzer et al., 2012). We identified as our top candidate a novel transcript associated with the gene encoding the glycolytic enzyme Phosphoglycerate Kinase-1 (Pgk1) (Figure 3—figure supplement 1).

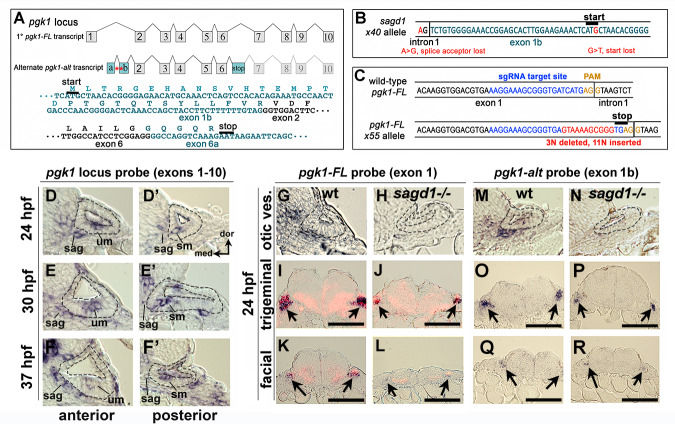

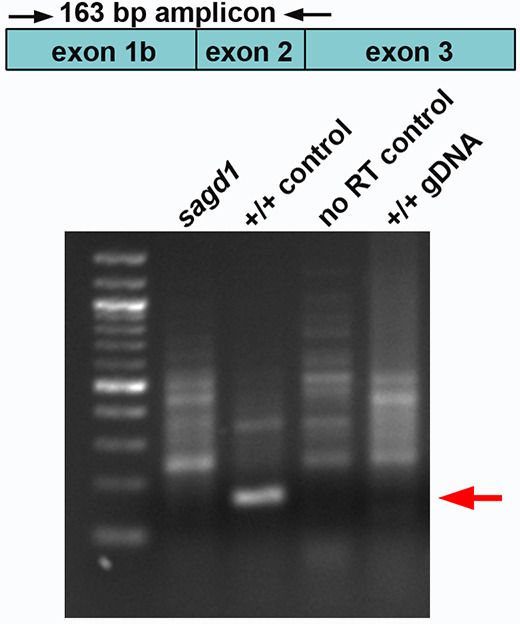

The zebrafish genome harbors only one pgk1 gene, but the locus produces two distinct transcripts (Figure 3A). The primary transcript (pgk1-FL) encodes full-length Pgk1, which is highly conserved amongst vertebrates (nearly 90% identical between zebrafish and human). However, the second pgk1 transcript, termed pgk1-alt, is unique to zebrafish and arises from an independent transcription start site in the first intron of pgk1-FL. The expression and sequence of pgk1-alt transcript were confirmed by conducting RT-PCR on mRNA harvested from wild-type embryos at 24 hpf (Figure 3—figure supplement 2). There are two short exons (termed exons 1a and 1b) at the start of pgk1-alt that encode a novel peptide with either 17 or 31 amino acids, depending on translation start site (see below). pgk1-alt then splices in-frame with exons 2–6, which are identical to pgk1-FL, followed by a splice into a novel exon (termed exon 6a) containing an in-frame stop codon (Figure 3A). Exon 6a then splices into exon 7, after which the sequence is identical to pgk1-FL. Thus pgk1-alt encodes a truncated protein that includes much of the N-terminal half of Pgk1 but presumably lacks glycolytic enzyme activity as the C-terminal peptide is required for ADP/ATP binding. In sagd1- / - mutants, pgk1-alt contains two nucleotide substitutions leading to loss of a splice acceptor site as well as the translation start codon in exon 1b (Figure 3B). Either of these SNPs could potentially disrupt expression of pgk1-alt protein. pgk1-alt transcript abundance is strongly reduced in sagd1 mutants (Figure 3—figure supplement 2).

Figure 3. Two independent transcripts associated with the pgk1 locus.

(A) Exon-intron structure of the primary full-length pgk1 transcript (pgk1-FL) and alternate transcript (pgk1-alt) arising from an independent transcription start site containing two novel exons (1a and 1b) that splice in-frame to exon 2, and a third novel exon (6a) containing a stop codon. The nucleotide and peptide sequences of exons 1b and 6a are shown. Relative positions of the lesions in sagd1 affecting exon 1b are indicated (red asterisks). (B) Nucleotide sequence near the 5’ end of exon 1b showing the SNPs detected in sagd1 (red font). (C) Nucleotide sequence of pgk1-FL showing the sgRNA target site (blue font) and the altered sequence of the x55 mutant allele (red font), which introduces a premature stop codon. (D–F’) Cross sections through the otic vesicle (outlined) showing staining with ribo-probe for the entire pgk1 locus (covering both pgk1-FL and pgk1-alt) in wild-type embryos. Note elevated expression in the SAG, utricular macula (um), and saccular macula (sm). (G, H, M, N) Cross sections through the otic vesicle (outlined) in wild-type embryos and sagd1 mutants stained with ribo-probe for exon 1 (pgk1-FL alone) (G, H) or exon 1b (pgk1-alt alone) (M, N). Accumulation of both transcripts is dramatically reduced in sagd1 mutants. (I–L, O–R) Cross sections through the hindbrain (dorsal up) showing expression of pgk1-FL (black) plus neurod (red) (I–L) or pgk1-alt alone (O–R). Arrows indicate positions of the trigeminal and facial ganglia. Scale bar, 100 µm.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Mapping of SNPs linked to sagd1.

Figure 3—figure supplement 2. RT-PCR identification of pgk1-alt.

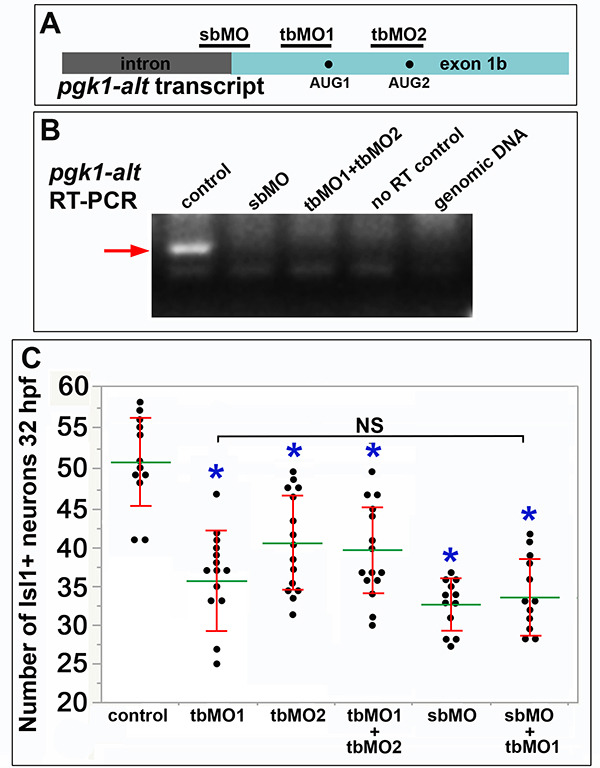

Figure 3—figure supplement 3. Morpholinos for pgk1-alt phenocopy sagd1.

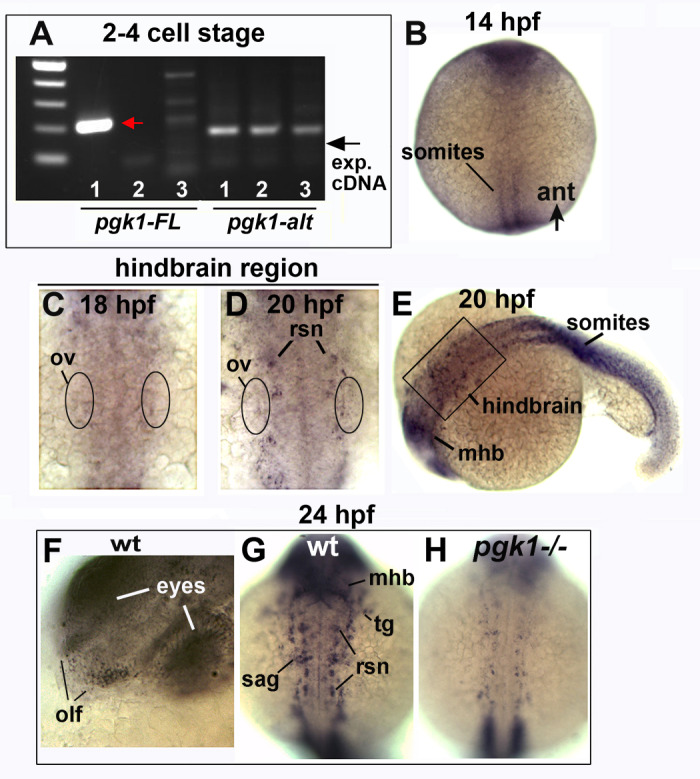

Figure 3—figure supplement 4. Expression of pgk1-FL during development.

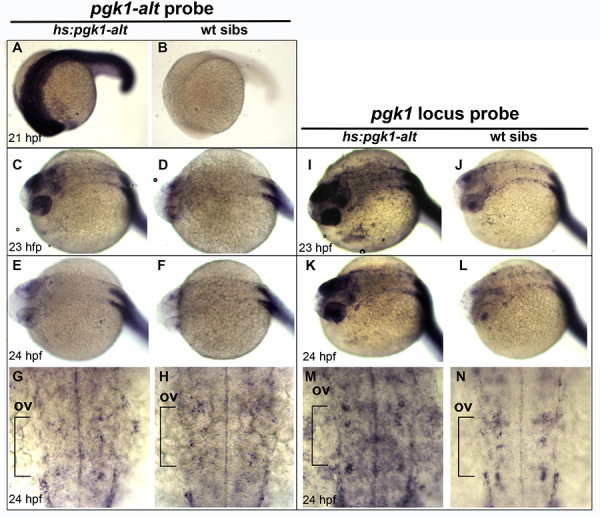

Figure 3—figure supplement 5. pgk1-alt misexpression increases pgk1 transcript abundance.

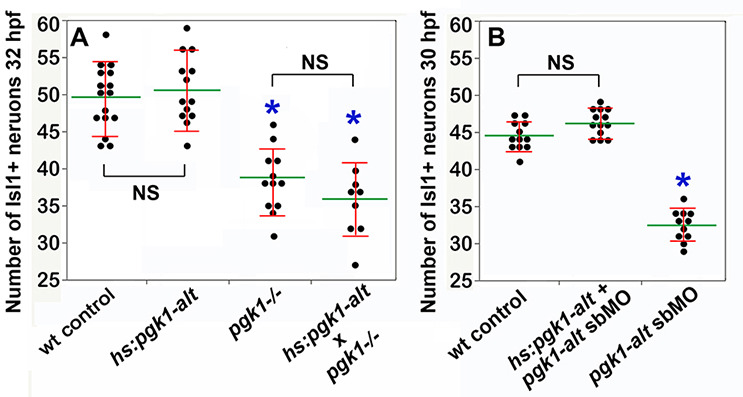

To determine which SNP in sagd1 is most relevant, we tested morpholinos (MOs) designed to mimic either mutation. Injecting wild-type embryos with a splice-blocker to target the exon 1b splice acceptor site (sbMO, Figure 3—figure supplement 3A) impaired accumulation of pgk1-alt transcript (Figure 3—figure supplement 3B) and reduced accumulation of Isl1+ SAG neurons by nearly 40% (Figure 3—figure supplement 3C). To design translation blockers (tbMOs), we considered that exon1b contains two in-frame AUG codons that could potentially serve as translation start sites, although the first site (disrupted in sagd1) lacks a Kozak consensus. We therefore designed tbMO1 and tbMO2 to target each start site (Figure 3—figure supplement 3A). It has been established that MOs can effectively block translation by binding mRNA near the start site and up to 80 nucleotides upstream, whereas binding >10 nucleotides downstream is ineffective (gene-tools.com). Therefore, tbMO1 is expected block translation from either start site whereas tbMO2 is predicted to block only the second start site. Injecting either translation blocker alone, or in combination, reduced accumulation of Isl1+ SAG neurons by 20–30% (Figure 3—figure supplement 3C). The phenotype produced by tbMO2 suggests that the second ATG is more likely to serve as the translation start site, in which case altering the first AUG should not disrupt pgk1-alt function. Thus, the first SNP in sagd1 that disrupts the exon 1b splice acceptor is the likely cause of the mutant phenotype. Interestingly, the translation blockers also impaired accumulation of pgk1-alt transcript (Figure 3—figure supplement 3B), suggesting that Pgk1-alt protein is required for normal transcript accumulation.

Although sagd1 does not alter the sequence of pgk1-FL, we examined whether the sagd1 mutation alters accumulation of pgk1-FL transcript. In wild-type embryos pgk1-FL transcript (but not pgk1-alt) is maternally deposited and is widely expressed at a low level during subsequent stages of development (Figure 3—figure supplement 4A). By 14 hpf pgk1-FL upregulates in developing somites (Figure 3—figure supplement 4B), and beginning around 18–20 hpf pgk1-FL transcript abundance becomes elevated in clusters of cells scattered throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems (Figure 3—figure supplement 4C–E). Examples of cells with elevated pgk1-FL expression include utricular and saccular hair cells, mature SAG neurons, trigeminal and epibranchial ganglia, the midbrain-hindbrain border, reticulospinal neurons in the hindbrain, and the olfactory epithelium (Figure 3D–G,I,K and Figure 3—figure supplement 4D–G). A similar pattern is observed for accumulation of pgk1-alt transcript (Figure 3M,O,Q). Local upregulation of pgk1-FL and pgk1-alt is severely attenuated in the nervous system in sagd1- / - mutants (Figure 3D–R), whereas expression remains elevated in somites (data not shown).

To test whether Pgk1-alt function is sufficient to upregulate pgk1-FL, we examined the effects of transient misexpression using a heat shock-inducible transgene, hs:pgk1-alt. When hs:pgk1-alt was activated at 20 hpf, accumulation of pgk1-FL was markedly elevated at 23–24 hpf (Figure 3—figure supplement 5I–N). This was in contrast to accumulation of transgenic pgk1-alt transcript, which peaked near the end of the heat shock period at 21 hpf but then decayed to background levels by 24 hpf (Figure 3—figure supplement 5A–H). We infer that perdurance of Pgk1-alt protein is sufficient to upregulate pgk1-FL. Based on previous studies of yeast and mammalian Pgk1 (Beckmann et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2010; Liao et al., 2016; Ruiz-Echevarria et al., 2001; Shetty et al., 2010; Shetty et al., 2004), it is possible that Pgk1-alt acts to stabilize pgk1-FL transcript (See Discussion).

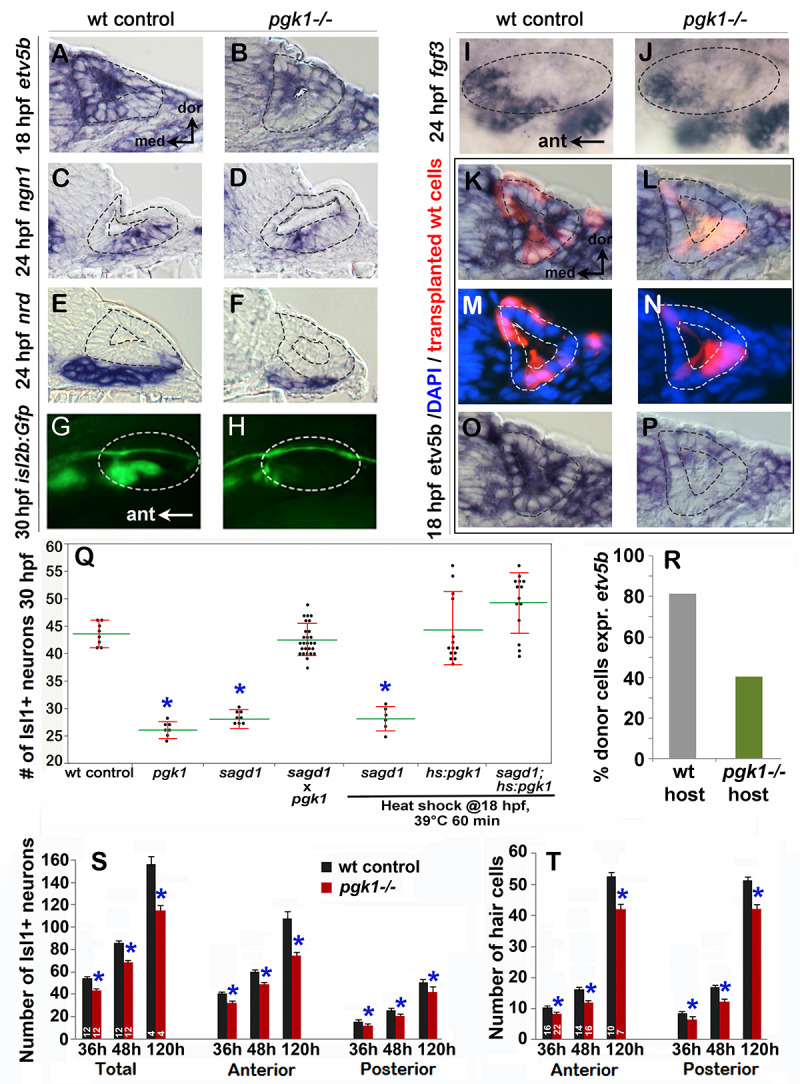

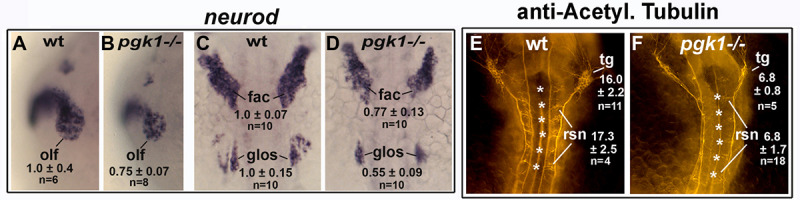

To directly test the requirement for full length Pgk1, we targeted the first exon of pgk1-FL using CRISPR-Cas9 and recovered an indel mutation leading to a frameshift followed by a premature stop (Figure 3C). This presumptive null mutation is predicted to eliminate all but the first 19 amino acids of Pgk1. Expression of pgk1 is severely reduced in pgk1- / - mutants, presumably reflecting nonsense-mediated decay (Figure 3—figure supplement 4H). The phenotype of pgk1- / - mutants is nearly identical to sagd1-/-: Despite apparently normal early expression of fgf3 and fgf8a, pgk1- / - mutants show impaired responses to early Fgf signaling, including reduced otic expression of pax5 and etv5b at 18 hpf, reduced ngn1 at 24 hpf, a deficiency in neurod+ transit-amplifying cells at 24 hpf, and a deficiency in mature isl2b-gfp+ SAG neurons at 30 hpf (Figure 4A–H,Q; Figure 4—figure supplement 1). The deficiency of Isl1+ SAG neurons persisted through at least 5 dpf (Figure 4—figure supplement 1). Unlike sagd1 mutants, however, pgk1- / - mutants showed a deficiency in both anterior and posterior SAG neurons (reduced 31% and 18%, respectively, at 5 dpf, Figure 4—figure supplement 1). pgk1- / - mutants also showed a 20–25% decrease in the number of utricular and saccular hair cells at 36 hpf, 48 hpf and five dpf (Figure 4T). Other aspects of otic vesicle patterning appeared normal based on expression of regional markers otx1, pou3f3b, hmx3a and dlx3b at 24 hpf (Figure 4—figure supplement 2). Beyond the inner ear, development of a number of other Fgf-dependent neural cell types are also deficient in pgk1- / - mutants, including trigeminal, facial and glossopharyngeal ganglia, reticulospinal neurons in the hindbrain, and the olfactory epithelium (Figure 4—figure supplement 3). Although pgk1- / - mutants show overtly normal gross morphology, they eventually die around 10–12 days post-fertilization. When pgk1+ / - heterozygotes were crossed with sagd1+ / - heterozygotes, all intercross embryos developed normally (Figure 4Q), confirming that pgk1-alt and pgk1-FL encode distinct complementary functions. We also generated a heat-shock inducible transgene to overexpress pgk1-FL (hs:pgk1). Activation of hs:pgk1 at 18 hpf rescued the SAG deficiency in sagd1- / - mutants (Figure 4Q). In contrast, activation of hs:pgk1-alt at 18 hpf was not able to rescue pgk1- / - mutants (Figure 4—figure supplement 4A), whereas activation of hs:pgk1-alt at 18 hpf did rescue morphants injected with pgk1-alt-sbMO (Figure 4—figure supplement 4B). Together, these data show that pgk1-alt is required upstream to locally upregulate pgk1-FL, which in turn is required for proper Fgf signaling and development of sensory hair cells, SAG neurons and various other Fgf-dependent neurons in the head.

Figure 4. Initial characterization of pgk1- / - mutants and genetic mosaics.

(A–F) Cross sections through the anterior/vestibular region of the otic vesicle (outlined) showing expression of the indicated genes in wild-type embryos and pgk1- / - mutants at the indicated times. (G–J) Lateral views showing isl2b-Gfp expression in live embryos at 30 hpf (G, H) and fgf3 at 24 hpf (I, J). The otic vesicle is outlined. (K–P) Cross sections through the otic vesicle (outlined) showing positions of lineage labeled wild-type cells (red dye) transplanted into a wild-type host (K, M, O) or a pgk1- / - mutant host (L, N, P). Sections are co-stained with DAPI (M, N) and etv5b probe (O, P). Note the absence of etv5b expression in wild-type cells transplanted into the mutant host (P). (Q) Number of mature Isl1+ SAG neurons at 30 hpf in embryos with the indicated genotypes, except for sagd1 x pgk1 intercross expected to contain roughly 25% each of +/+, sagd1/+, pgk1/+ and sagd1/pgk1 embryos. (R) Percent of wild-type donor cells located in the ventral half of the otic vesicle expressing etv5b in wild-type or pgk1- / - hosts. A total of 151 wild-type donor cells were counted in eight otic vesicles of wild-type host embryos, and 247 wild-type donor cells were counted in eight otic vesicles of pgk1- / - host embryos. (S) Number of Isl1+ SAG neurons (total, anterior and posterior) in wild-type and pgk1- / - mutant embryos at 36 hpf (n = 12), 48 hpf (n = 12) and 120 hpf (n = 4). (T) Number of phalloidin-stained hair cells (anterior/utricular and posterior/saccular) in wild-type and pgk1- / - mutant embryos at 36 hpf (n = 16), 48 hpf (n = 16) and 120 hpf (n = 10). Sample sizes are indicated (S, T).

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. pgk1– / - mutants show normal onset of fgf3 and fgf8a, but not pax5, in the otic vesicle.

Figure 4—figure supplement 2. pgk1– / - mutants show normal expression of regional markers of the otic vesicle.

Figure 4—figure supplement 3. Deficiencies in Fgf-dependent cell types in pgk1- / - mutants.

Figure 4—figure supplement 4. Misexpression of pgk1-alt does not rescue pgk1- / - mutants but does rescue pgk1-alt morphants.

Figure 4—figure supplement 5. Fgf signaling is not required for normal pgk1-FL expression.

Figure 4—figure supplement 6. Knockdown of plasminogen does not alter pgk1- / - or sagd1- / - phenotypes.

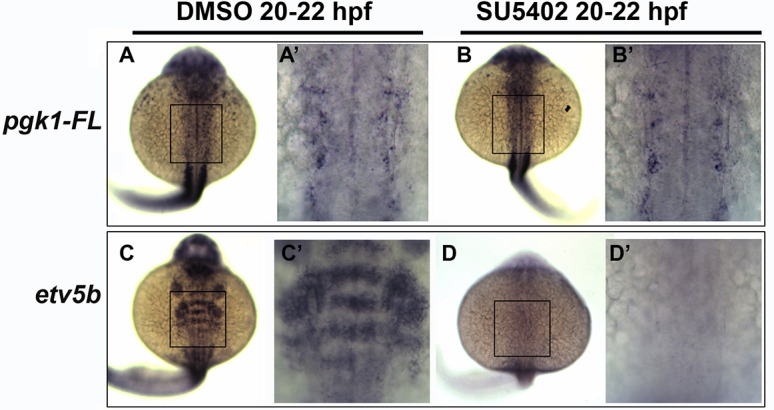

Pgk1 acts non-autonomously to promote fgf signaling

We note that sites of upregulation of pgk1-FL and pgk1-alt occurs within or near sites of expression of various Fgf ligands, including sensory epithelia, mature SAG neurons, and other tissues depicted in Figure 3—figure supplement 4F–G (Reifers et al., 1998; Thisse et al., 2001; Millimaki et al., 2007; Feng and Xu, 2010; Terriente et al., 2012; Vemaraju et al., 2012). Since expression of fgf3 and fgf8a does not depend on pgk1 (Figure 2S-T, Figure 4I-J, Figure 4—figure supplement 1), we asked whether upregulation of pgk1 depends on Fgf. We found that local upregulation of pgk1 occurred normally in embryos treated with the Fgf pathway-inhibitor SU5402 (Figure 4—figure supplement 5). Thus, pgk1 and fgf genes are not required for each other’s expression but could share a common upstream regulator.

To better understand how Pgk1 promotes Fgf signaling during otic development, we generated genetic mosaics by transplanting wild-type donor cells into pgk1- / - mutant host embryos. We reasoned that if Pgk1 acts cell-autonomously, as expected for a glycolytic enzyme, then isolated wild-type cells should be able to respond to local Fgf sources within a pgk1- / - mutant host. Surprisingly, the majority of the wild-type cells located near the utricular Fgf source in the floor of the otic vesicle in pkg1- / - hosts did not express the Fgf-target etv5b (Figure 4J,L,N,P,R). In control experiments, wild-type cells transplanted into wild-type hosts showed normal expression of etv5b (Figure 4I,K,M,O,R). Thus, Pgk1 is required non-autonomously to promote Fgf signaling at a distance.

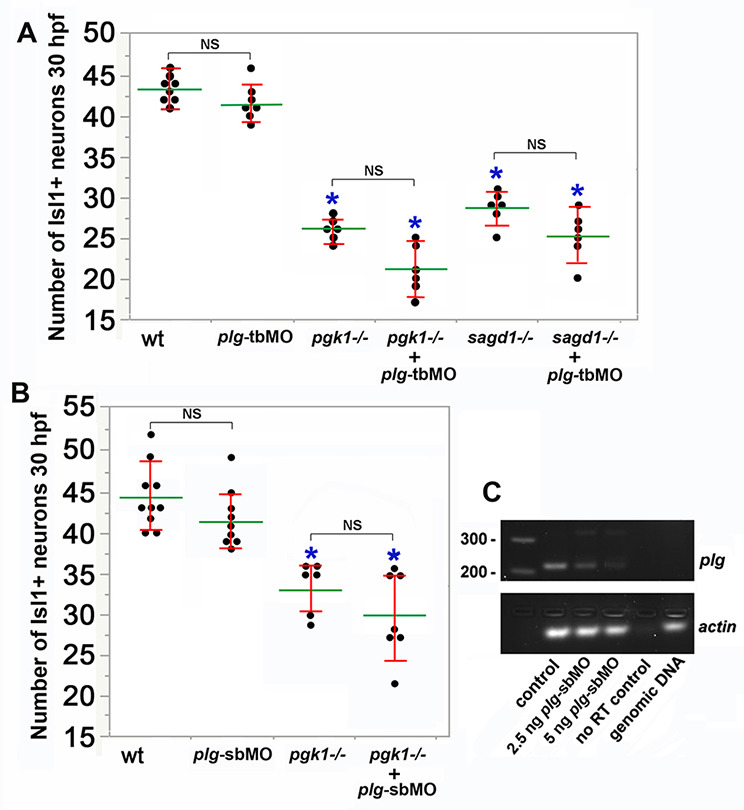

Pgk1 does not act extracellularly through plasmin turnover

We considered two distinct mechanisms for non-autonomous functions of Pgk1 that have been documented in metastatic tumors. First, tumor cells secrete Pgk1 to promote early stages of metastasis through modulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) and cell signaling (Chirico, 2011; Jung et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2010). The only specific molecular function identified for secreted Pgk1 is to serve as a disulfide reductase leading to proteolytic cleavage of Plasmin (Lay et al., 2000), a serine protease that cleaves Fgf as well as ECM proteins required for Fgf signaling (Botta et al., 2012; George et al., 2001; Meddahi et al., 1995; Schmidt et al., 2005). This raised the possibility that loss of Pgk1 could elevate Plasmin activity and thereby impair Fgf signaling. To test this, we injected translation-blocking morpholino (plg-tbMO) to block synthesis of Plasminogen (Plg), the zymogen precursor of Plasmin. Injection of plg-tbMO did not rescue or ameliorate the neural deficiency in sagd1- / - or pgk1- / - mutants (Figure 4—figure supplement 6A). We also tested a splice-blocker (plg-sbMO) to validate MO efficacy. Injection of plg-sbMO effectively attenuated plg transcript (Figure 4—figure supplement 6C) but did not rescue pgk1- / - mutants (Figure 4—figure supplement 6B). Therefore the effects of pgk1- / - and sagd1- / - do not depend on accumulation of Plasmin.

Aerobic glycolysis is required for otic development

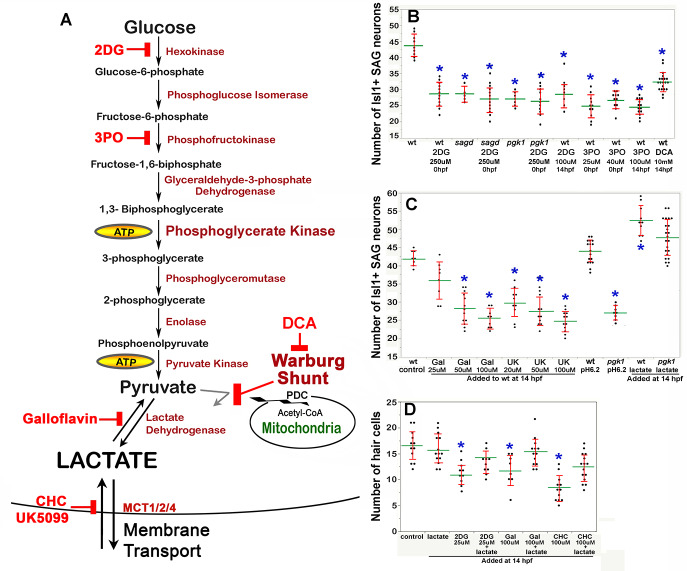

The second Pgk1-dependent mechanism employed by metastatic tumors is to upregulate and redirect glycolysis to promote lactate synthesis despite abundant oxygen. This process is often called ‘aerobic glycolysis’, or the ‘Warburg Effect’, and is thought to accelerate synthesis of ATP and provide 3-carbon polymers used for rapid biosynthesis (Liberti and Locasale, 2016). In addition, lactate secretion facilitates cell signaling in cancer cells (San-Millán and Brooks, 2017) as well as during certain normal physiological contexts (Lee et al., 2015; Peng et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2014; Zuo et al., 2015; Reviewed by Philp et al., 2005). We therefore tested whether blocking glycolysis and/or lactate synthesis in wild-type embryos could mimic the phenotype of pgk1- / - and sagd1- / - mutants. Treating wild-type embryos with 2-deoxy-glucose (2DG) (Nirenberg and Hogg, 1958) or 3PO (Clem et al., 2008) to block early steps in glycolysis (Figure 5A) reduced the number of mature SAG neurons to a level similar to that of pgk1- / - or sagd1- / - mutants (Figure 5B). Similar results were obtained when these inhibitors were added at 0 hpf or 14 hpf.

Figure 5. Drugs blocking aerobic glycolysis mimic pgk1- / - mutants.

(A) Diagram of the glycolytic pathway and changes associated with the Warburg Effect in which pyruvate is shunted from mitochondria in favor of synthesis and secretion of lactate. The indicated inhibitors were used to block discrete steps in the pathway. In the Warburg Shunt, mitochondrial Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex (PDC) is inhibited by elevated Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase (PDK), the activity of which is blocked by DCA. (B, C) Scatter plots showing the mean (green) and standard deviation (red) of the number of Isl1/2+ SAG neurons at 30 hpf in embryos with the indicated genotypes and/or drug treatments. Lactate-treatments and some controls were buffered with 10 mM MES at pH 6.2. (D) Scatter plats showing the mean and standard deviation of the total number of hair cells at 36 hpf in embryos treated with the indicated drugs. Asterisks show significant differences (p ≤. 05) from wild-type control embryos.

We next focused on later steps in the pathway dealing with handling of pyruvate vs. lactate. In cells exhibiting the Warburg Effect, transport of pyruvate into mitochondria is typically blocked by upregulation of Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase (PDK) (Cairns et al., 2011), thereby favoring reduction of pyruvate to lactate (see Warburg Shunt, Figure 5A). Dichloroacetate (DCA) blocks PDK activity (Kato et al., 2007), allowing more pyruvate to be transported into mitochondria and thereby forestalling lactate synthesis. Treating wild-type embryos with DCA at 14 hpf mimicked the deficiency of SAG neurons seen in pgk1- / - and sagd1- / - mutants (Figure 5B). To directly block synthesis of lactate from pyruvate, wild-type embryos were treated with Galloflavin, an inhibitor of Lactate Dehydrogenase (Farabegoli et al., 2012; Manerba et al., 2012; Figure 5A). Wild-type embryos treated with Galloflavin at 14 hpf also displayed a deficiency of SAG neurons similar to pgk1- / - and sagd1- / - mutants (Figure 5C). Finally, to block transport of lactate across the cell membrane, we treated wild-type embryos with either CHC or UK5099, which block activity of monocarboxylate transporters MTC1, 2 and 4 (Halestrap, 1975; Halestrap and Denton, 1974; Figure 5A). Application of either CHC or UK5099 at 14 hpf also mimicked the SAG deficiency in pgk1- / - and sagd1- / - mutants (Figure 5C, and data not shown). Treatment of wild-type embryos with 2DG, Galloflavin or CHC also reduced hair cell production to a level comparable to sagd1- / - or pgk1- / - mutants (Figure 5D). To further explore the role of lactate, we added exogenous lactate to embryos beginning at 14 hpf and examined accumulation of SAG neurons at 30 hpf. As shown in Figure 5C, lactate treatment elevated SAG accumulation above normal in wild-type embryos and fully rescued pgk1- / - mutants. Lactate treatment also rescued hair cell production in wild-type embryos treated with 2DG, Galloflavin, or CHC (Figure 5D). Thus, pharmacological agents that block glycolysis, lactate synthesis or lactate secretion are sufficient to mimic the pgk1- / - and sagd1- / - phenotype, and exogenous lactate is sufficient to reverse these effects.

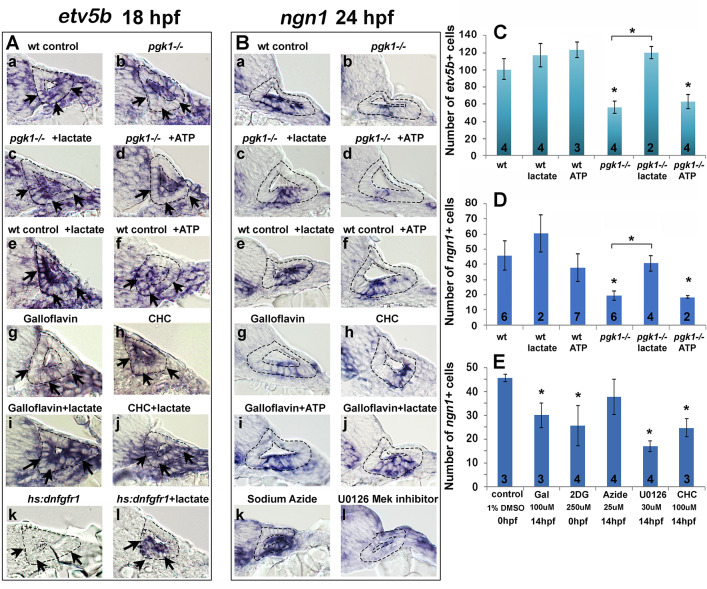

We next examined whether the above inhibitors and/or exogenous lactate affect Fgf signaling and SAG specification in the nascent otic vesicle. Treatment of wild-type embryos with Galloflavin or CHC reduced the number of cells expressing etv5b and ngn1 at 18 hpf and 24 hpf, respectively (Figure 6Ag, Ah, Bg, Bh, E), mimicking the effects of pgk1-/- (Figure 6Ab, Bb, C, D). Treatment with exogenous lactate reversed the effects of Galloflavin and CHC (Figure 6Ai, Aj, Bj) and rescued pgk1- / - mutants (Figure 6Ac, Bc, C, D). Moreover, treating wild-type embryos with lactate increased the number of cells expressing etv5b and ngn1 (Figure 6Ae, Be, C, D).

Figure 6. Exogenous lactate reverses the effects of disrupting aerobic glycolysis.

(A, B) Cross sections through the anterior/vestibular portion of the otic vesicle (outlined) showing expression of etv5b at 18 hpf (A) and ngn1 at 24 hpf (B) in embryos with the indicated genotype or drug treatment. Arrows in (A) highlight expression in the ventromedial otic epithelium. (C) Mean and standard deviation of the number of etv5b+ cells in the ventral half of the otic vesicle counted from serial sections of embryos with the indicated genotype or drug treatment. (D, E) Mean and standard deviation of the number of ngn1+ cells in the floor of the otic vesicle counted from serial sections of embryos with the indicated genotype or drug treatment. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p<0.05) from wild-type controls, or between groups indicated by brackets.

Figure 6—figure supplement 1. Exogenous ATP does not rescue pgk1- / - mutants.

Figure 6—figure supplement 2. Effects of altering MAPK/Erk, lactate and Fgf on SAG development.

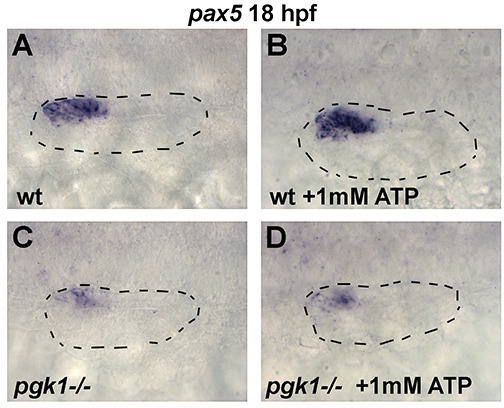

We also tested whether a deficiency of ATP contributes to the pgk1- / - phenotype. Adding exogenous ATP to pgk1- / - mutants at 14 hpf did not ameliorate the deficiency in expression of etv5b, ngn1, or pax5 (Figure 6Ad, Bd, C, D; and Figure 6—figure supplement 1). Likewise, adding ATP to wild-type embryos at 14 hpf did not significantly affect expression of these genes (Figure 6Af, Bf, C, D; and Figure 6—figure supplement 1). Finally, adding 25 uM sodium azide to wild-type embryos at 14 hpf to block mitochondrial respiration did not significantly impair expression of ngn1 at 24 hpf (Figure 6Bk, E). Thus, lactate is critical for early Fgf signaling and SAG specification, but exogenous ATP does not affect these functions. Moreover, the deficiencies in otic development observed in pgk1- / - mutants can be attributed to disruption of lactate synthesis and secretion.

Lactate and fgf act in parallel to regulate early otic development

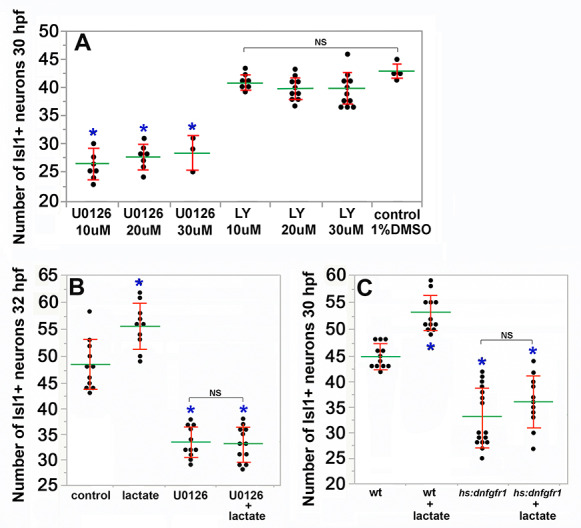

Fgf regulates gene expression primarily through the PI3K and MAPK/Erk signal transduction pathways, but it is unknown which is most critical for otic development. Treatment of wild-type embryos with U0126, an inhibitor of the MAPK activator Mek (Hawkins et al., 2008), reduced the number of ngn1+ cells at 24 hpf (Figure 6Bl, E) and mature Isl1+ SAG neurons at 30 hpf (Figure 6—figure supplement 2A) to a degree similar to or greater than pgk1- / - mutants. In contrast, treatment of wild-type embryos with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (Montero et al., 2003) had negligible effects on these genes (Figure 6—figure supplement 2A, and data not shown), showing that most of the effects of Fgf are mediated by MAPK/Erk.

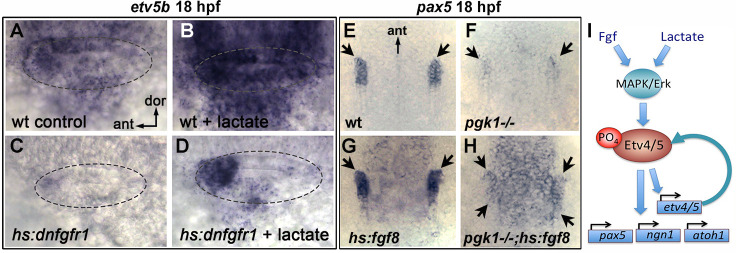

Recent findings show that lactate can activate the MAPK/Erk pathway through Ras-independent activation of Raf kinase (Lee et al., 2015), see Discussion). Consistent with this mechanism, the ability of lactate to stimulate production of SAG neurons was completely blocked by co-treatment with U0126 (Figure 6—figure supplement 2B). We next investigated whether lactate treatment can bypass the requirement for Fgf signaling. Transient misexpression of dominant negative Fgf receptor from a heat shock-inducible transgene, hs:dnfgfr1, fully suppressed etv5b expression within two hours of heat shock (Figure 6Ak; Figure 7C) and reduced accumulation of SAG neurons by 25% at 30 hpf (Figure 6—figure supplement 2C). Importantly, treatment with exogenous lactate partially restored etv5b expression when Fgf signaling was blocked (Figure 6Al; Figure 7D), although this was not sufficient to restore development of SAG neurons (Figure 6—figure supplement 2C). Because developmental defects in pgk1- / - and sagd1- / - mutants appear to stem from reduced Fgf signaling, we tested whether elevating Fgf can rescue pgk1- / - mutants. Activation of hs:fgf8 at a moderate level (37°C for 30 min) beginning at 16 hpf increased the level of pax5 expression in the otic vesicle at 18 hpf and expanded the spatial domain (Figure 7E,G). Activation of hs:fgf8 in pgk1- / - mutants increased expression of pax5 relative to pgk1- / - alone (Figure 7F,H), but not to the same degree seen in non-mutant embryos. Thus, elevating either Fgf or lactate alone can partially compensate for loss of the other, but full activation of early otic genes requires both Fgf and lactate to fully activate the MAPK/Erk pathway.

Figure 7. Fgf and lactate are required together for full activation of early otic genes.

(A–D) Dorsolateral view of the otic vesicle (outlined) showing expression of etv5b at 18 hpf in wild-type embryos or hs:dnfgfr1/+ transgenic embryos with or without exogenous 6.7 mM lactate added at 14 hpf, as indicated. Embryos were heat shocked at 39°C for 30 min beginning at 16 hpf. (E–H) Dorsal view (anterior to the top) of the hindbrain and otic region showing expression of the otic domain of pax5 (black arrows) in embryos with the indicated genotypes. Embryos were heat shocked at 37°C for 30 min beginning at 16 hpf. (I) A model for how lactate and Fgf signaling converge on MAPK/Erk to increase the pool of phosphorylated activated Etv4/5, enabling cells to respond more quickly and robustly to dynamic changes in Fgf.

Discussion

Enhanced glycolysis and lactate secretion promote fgf signaling

Metabolic pathways such as glycolysis have traditionally been viewed as ‘house keeping’ functions but are increasingly recognized for their specific roles in development. We discovered that mutations in pgk1 cause specific defects in formation of hair cells and SAG neurons of the inner ear, as well as the olfactory epithelium and various cranial ganglia and reticulospinal neurons of the hindbrain, all of which normally show elevated expression of pgk1 (Figure 3) and require Fgf signaling (Lassiter et al., 2009; Maulding et al., 2014; Millimaki et al., 2007; Nechiporuk et al., 2005; Terriente et al., 2012; Vemaraju et al., 2012). Treatment of wild-type embryos with specific inhibitors of glycolysis or lactate synthesis or secretion mimicked the effects of pgk1-/-, indicating that the affected cell types require ‘aerobic glycolysis’, similar to the Warburg Effect exhibited by metastatic tumors. Developmental deficiencies seen in pgk1- / - mutants reflect weakened response to Fgf but are fully rescued by treatment with exogenous lactate. Lactate has been shown to bind and stabilize the cytosolic protein Ndrg3, which in turn activates Raf (Lee et al., 2015) thereby converging with Fgf signaling to activate MAPK/Erk. In support of this mechanism, the stimulatory effects of lactate are blocked by the Mek-inhibitor U0126. The MAPK/Erk pathway activates transcription of etv4 and etv5a/b genes (Raible and Brand, 2001; Roehl and Nüsslein-Volhard, 2001). Etv4/5 proteins are also phosphorylated and activated by MAPK/Erk and mediate many of the downstream effects of Fgf (Brown et al., 1998; O'Hagan et al., 1996; Znosko et al., 2010). This dual regulation of Etv4/5 implies a feedback amplification step and offers an explanation for why lactate is required to increase the efficiency of early stages of Fgf signaling (Figure 7I). Specifically, initial activation of MAPK/Erk by lactate would expand the pool of Etv4/5, priming cells to respond more quickly to dynamic changes in Fgf signaling. Without pgk1, the initial response to Fgf is sluggish and causes lasting deficits in SAG neurons and slows accumulation of hair cells. Later, as Fgf-mediated feedback amplification continues, Fgf signaling gradually improves on its own and is sufficient to support normal development of posterior SAG neurons in sagd1 mutants, although accumulation of SAG neurons and hair cell continues at a slower pace in pgk1- / - mutants.

It is interesting that sites of pgk1 upregulation correlate with sites of Fgf ligand expression. Fgf expression does not require pgk1 (Figure 2S–T’), and pgk1 upregulation does not require Fgf (Figure 4—figure supplement 5), suggesting co-regulation by shared upstream factor(s). Analysis of genetic mosaics showed that isolated wild-type cells transplanted into pgk1- / - host embryos failed to activate etv5b despite close proximity to sensory epithelia, a known Fgf-source. Clearly wild type cells retain the ability to perform glycolysis, but since upregulation of pgk1 in the otic vesicle is limited to sensory epithelia and mature SAG neurons (Figure 3A–G), other otic cells may be unable to generate sufficient lactate to augment Fgf signaling. This raises the interesting possibility that Fgf and lactate must be co-secreted from signaling sources to support full signaling potential. Indeed, this model explains why SAG neuroblasts in the otic vesicle, which do not detectably express pgk1 or fgf genes, require both to be expressed in nearby tissues for proper specification. Note, we cannot exclude the possibility that lactate acts cell-autonomously to promote secretion of Fgf ligand, but such a mechanism has never been reported and does not explain why blocking lactate transport mimics the effects of pgk1- / - and sagd1 mutations.

Regulation of Pgk1 by Pgk1-alt

The sagd1 mutation does not directly affect full length Pgk1, but instead disrupts a novel transcript arising from an independent downstream transcription start site that appears to reflect an ancient transposon insertion. The first 17 amino acids of Pgk1-alt are novel but downstream the sequence is identical to exons 2–6 of Pgk1-FL. Production of Pgk1-alt is necessary and sufficient for upregulation of pgk1-FL, possibly involving transcript stabilization. Exon 6 of zebrafish Pgk1-FL and Pgk1-alt corresponds closely to the STE (stabilizing element) of yeast Pgk1 (Ruiz-Echevarria et al., 2001). Premature stops within the first half of yeast Pgk1 lead to nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) of the transcript, but later stops (occurring downstream of the STE) do not trigger NMD (Hagan et al., 1995). The STE can also stabilize recombinant transcripts containing foreign sequences that include a 3’UTR that normally destabilizes the transcript independent of NMD. In each case the STE must be translated in order to function, raising the possibility that the corresponding peptide is required for stability (Ruiz-Echevarria et al., 2001). Several recent studies have identified full length Pgk1 in yeast and human as an unconventional mRNA-binding protein (Beckmann et al., 2015; Liao et al., 2016), and human Pgk1 can bind specific mRNAs to affect stability, though often by destabilization (Ho et al., 2010; Shetty et al., 2004). Whether Pgk1 increases or decreases mRNA stability could reflect interactions with specific sequences or secondary structures in the target. In any case, it seems reasonable that the STE of Pgk1-alt has been coopted from an established ‘moonlighting’ function of Pgk1 to locally upregulate pgk1-FL by increasing transcript stability, thereby facilitating the switch to Warburg metabolism.

Despite the requirement for pgk1-alt in the developing nervous system, it is not required in mesodermal tissues. For example, upregulation of pgk1 in developing somites is not affected in sagd1- / - mutants. Curiously, pgk1 is not appreciably upregulated in presomitic mesoderm, despite the fact that somitogenesis involves a gradient of aerobic glycolysis and lactate synthesis that is highest in the tail and declines anteriorly (Bulusu et al., 2017; Oginuma et al., 2017; Ozbudak et al., 2010). However, establishment of Warburg-like metabolism does not necessarily require elevated pgk1. Conversely, elevated pgk1 does not necessarily indicate a Warburg-like state. Indeed, upregulation of pgk1 in somites likely provides high levels of pyruvate to favor robust mitochondrial ATP synthesis over lactate synthesis (Ozbudak et al., 2010). Although we detected no obvious defects in somite formation in pgk1- / - or sadg1- / - mutants, it is possible that later aspects of somite differentiation, muscle physiology, etc. are affected.

Although the sagd1 mutation was recovered in a forward ENU mutagenesis screen, we note that the SNPs detected in the pgk1-alt sequence were previously reported in the genome sequence database. It is therefore likely that familial breeding during our screen allowed generation and detection of homozygous carriers of this preexisting allele. Indeed, we have subsequently detected these SNPs in our wild-type stock, likely accounting for variation in expression levels in early otic genes sometimes detected in specific families. As a cautionary note, the sequence for pgk1-alt was initially represented in older versions of the annotated zebrafish genome but has since been removed, presumably deemed a technical artifact. However, RT-PCR amplification of sequences expressed at 24 hpf confirmed the presence of pgk1-alt. Had we used more recent versions of the genome as our reference dataset, the SNPs in sagd1 would have been overlooked. Regardless of its origins, identification of the sagd1 mutant allele underscores the continuing utility of forward screens: Had we not recovered sagd1 from our screen, it is highly unlikely that we would have identified pgk1 as a developmental regulatory gene.

Materials and methods

Fish strains and developmental conditions

Wild-type embryos were derived from the AB line (Eugene,OR). For most experiments embryos were maintained at 28.5°C, except where noted. Embryos were staged according to standard protocols (Kimmel et al., 1995). PTU (1-phenyl 2-thiourea), 0.3 mg/ml (Sigma P7629) was included in the fish water to inhibit pigment formation. The following transgenic lines were used in this study: Tg(hsp70:fgf8a)x17 (Millimaki et al., 2010), Tg(Brn3c:GAP43-GFP)s356t (Xiao et al., 2005), Tg(−17.6isl2b:GFP)zc7 (Pittman et al., 2008), Tg(hsp70I:dnfgfr1-EGFP)pd1 (Lee, 2005), and new lines generated for this study Tg(hsp70I:pgk1-FL)x65 and Tg(hsp70I:pgk1-alt)x66. These transgenic lines are herein referred to as hs:fgf8, brn3c:GFP, Isl2b:GFP, hs:pgk1-FL, hs:pgk1-alt, and hs:dnfgfr1 respectively. Mutant lines sagd1x40 and pgk1x55 were used for loss of function analysis. Homozygous sagd1- / - and pgk1- / - mutant embryos were identified by a characteristic decrease in the expression of Isl2b-Gfp observed at stages after 24 hpf. At earlier stages, homozygous pgk1- / - mutant embryos were identificed by indel-PCR genotyping using the following primers (5’−3’) in a single reaction: pgk1-fwd-1, AGGTCATTCTCATTCGGGAAC; pgk1-indel-1, AAGGAAAGCGGGTGATCATG; pgk1-rev-1, ACGTTAAAGGGCATACGACG. pgk1-fwd-1 produces an amplicon of ~250 bp from both wild-type and mutant DNA, whereas pgk1-indel-1 produces an amplicon of 127 bp from wild-type DNA only. Adult pgk1+ / - heterozygotes were identified using the following primers in a single reaction: pgk1-fwd-2, GCAAGTACATCCAATTGCCG; pgk1-indel-2, CGGGTGAGTAAAAGCGGG; pgk1-rev-2, ACGCGTGACAGATACACTTCC. pgk1-fwd-2 produces an amplicon of ~451 bp from both wild type and mutant DNA, whereas pgk1-indel-2 produces an amplicon of 236 bp from mutant DNA only. hs:pgk1-FL and hs:pgk1-alt carriers were identified by in situ hybridization using probes for pgk1-FL and pgk1-alt transcripts following heat-shock at 39°C for 1 hr, or by PCR genotyping using DNA extracted from tails of single embryos, and the following primers (5’−3’): hsp-Fwd, GACGAGGTGTTTATTCGCTCT; reverse primer, ACTGCAGCCTTGATTCTCTG, yielding an amplicon of ~700 bp.

Gene misexpression and morpholino injections

Heat-shock regimens were carried in a water bath at indicated temperatures and durations. Embryos were kept in a 33°C incubator after the heat-shock. Knockdown of pgk1-alt was performed by injecting wild-type embryos at the one-cell stage with ~5 ng of translation-blocking morpholino oligomer tbMO1 (5’-AGCATGAGTTTCTTCCAAGTGCACC-3’) or tbMO2 (5’-GTCAGTTGGCATTTCTGTGTGGACT-3’), or 10 ng of splice-blocker sbMO (5’-TCCCCACAGACTAAAGACAATCAGT-3’). Knockdown of plasminogen was performed by injecting one-cell embryos with ~5 ng of translation-blocker plg-tbMO (5’-AACTGCTTTGTGTACCTCCATGTCG-3’) or splice-blocker plg-sbMO (5’-AGCATCCTTACCTGTAAAAAGAAAG-3’). Although none of these knockdown conditions, by themselves, caused visible morphological changes or cell death, as a precaution all morpholinos were co-injected with ~5 ng p53-MO to suppress non-specific cell death.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR

For plg RT-PCR, RNA was extracted from groups of 50 embryos at 30 hpf using Trizol (Life Technologies) and chloroform (MACRON fine chemicals). For pgk1-FL and pgk1-alt RT-PCR, RNA was extracted from groups of 50 wild type embryos at 2–4 cell stage or 24 hpf using Trizol and chloroform or a total RNA miniprep kit (NEB), including an on-column DNase I treatment. Trizol and chloroform extracted samples were treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega), and re-purified using a RNA cleanup kit (zymo). Reverse transcriptions were performed in 20 μl reactions containing 0.9–1.5 μg of purified RNA, using SuperScript IV and SuperScript First-strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen). 1–3 μl of reverse transcription products were used as templates in PCR reactions, except for actin RT-PCR which 1:10 diluted reverse transcription products were used. RT-PCR were performed with Taq DNA polymerase (NEB) at extension temperature of 68°C. Gene/transcript specific primer pairs (5’−3’) and annealing temperatures are as follows: plg CGACATGGAGGTACACAAAG (Forward) and GAAGGACCTGCATGTAAAGG (Reverse), 49°C; pgk1-FL AGGTCATTCTCATTCGGGAAC (F) and ACTGCAGCCTTGATTCTCTG (R), 51°C; pgk1-alt AACTCATGCTAACACGGGGA (F) and ACTGCAGCCTTGATTCTCTG (R), 52.9°C; actin AGGTCATCACCATCGGCAAT (F) and CAATGAAGGAAGGCTGGAACAG (R), 49 or 49.7°C.

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

Whole mount in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry protocols used in this study were previously described (Phillips et al., 2001). Whole mount stained embryos were cut into 10 µm sections using a cryostat as previously described (Vemaraju et al., 2012). The following antibodies were used in this study: Anti-Islet1/2 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank 39.4D5, 1:100), Anti-GFP (Invitrogen A11122, 1:250), Alexa 546 goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (ThermoFisher Scientific A-11003/A-11010, 1:50). Promega terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (M1871) was used according to manufacturer’s protocol to perform the TUNEL assay.

Cell transplantation

Wild-type donor embryos were injected with a lineage tracer (tetramethylrhodamine labeled, 10,000 MW, lysine-fixable dextran in 0.2 M KCl) at one-cell stage and transplanted into non-labeled wild-type or pgk1 mutant embryos at the blastula stage. A total of 151 and 247 transplanted wild type cells were visualized in the ears of wild-type embryos and pgk1 mutants, respectively, (n = 8 otic vesicles each) and analyzed for the expression of etv5b.

Pharmacological treatments

The pharmacological inhibitors used in this study include Hexokinase inhibitor 2DG (2-Deoxy-Glucose, Sigma D8375), PFKFB3 inhibitor 3PO (Sigma SML1343), Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase inhibitor DCA (dichloroacetate, Sigma 347795), Lactate Dehydrogenase inhibitor Galloflavin (Sigma SML0776), MCT1/2/4 inhibitors CHC (á-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid, Sigma C2020) and UK-5099 (Sigma PZ0160), MEK inhibitor U1026 (Sigma U120) and PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (Sigma L9908). All inhibitors were dissolved in a 10 mm DMSO stock solution and diluted into the final indicated concentrations in fish water. Lactate treatments were performed with a 60% stock sodium DL-lactate solution (Sigma L1375) diluted 1 to 1000 in fish water to a final concentration of 6.7 mM, and buffered with 10 mm MES at pH 6.2. Note, lactate treatment has little effect on embryonic development at higher pH (not shown). Treatments were carried in a 24-well plate with a maximum of 15 embryos per well in a volume of 500 µl each.

Statistics and quantitation

Student’s t-test was used for pairwise comparisons. Analysis of 3 or more samples was performed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey post-hoc HSD test. Sufficiency of sample sizes was based on estimates of confidence limits. Sample sizes are indicated in Figures or legends. Hair cells were counted in whole mount specimens expressing brn3c:GFP, or by phalloidin-staining. Mature SAG neurons were counted by staining embryos with anti-Isl1/2 antibody and counting stained nuclei in whole mount preparations, or by counting isl2b:GFP+ SAG neurons in serial sections (2–4 embryos each) counter-stained with DAPI. For quantitation of gene expression patterns detected by in situ hybridization, stained cells were counted in serial sections (2–6 embryos each) counter-stained with DAPI. In some cases, as indicated in the text, whole mount gene expression domains were quantified from by measuring cross-sectional areas using Photoshop. Otherwise characteristic changes in whole mount gene expression reported herein were fully penetrant amongst mutant embryos but were not observed in wild-type embryos.

Whole genome sequencing and mapping analysis

Adult zebrafish males derived from the AB line were mutagenized using the alkylating agent N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) and outcrossed to Isl2b: GFP + females as previously described (Riley and Grunwald, 1995). sagd1 mutants were identified in the screening process due to the decreased expression of Isl2b:Gfp in vestibular SAG neurons. For the mapping analysis, sagd1 mutants were outcrossed to the highly polymorphic zebrafish WIK line. A genomic pool of 50 homozygous mutants were collected from the intercrosses between 3 pairs of heterozygous sagd1 carriers of the AB/WIK hybrid line and sent for whole genome sequencing at Genomic Sequencing and Analysis Facility (GSAF) at the University of Texas-Austin. Sequence reads were aligned using the BWA alignment software. Bulk segregant linkage and homozygosity mapping of the aligned sequences were performed using Megamapper (Obholzer et al., 2012). Both approaches identified the pgk1 locus as the top candidate lesion in sagd1 mutants.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sarah Ferguson for her help in processing whole genome sequence data. This work was funded by NIH-NIDCD grant R01-DC03806.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Contributor Information

Bruce B Riley, Email: briley@bio.tamu.edu.

Tanya T Whitfield, University of Sheffield, United Kingdom.

Marianne E Bronner, California Institute of Technology, United States.

Funding Information

This paper was supported by the following grant:

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders R01-DC03806 to Bruce B Riley.

Additional information

Competing interests

No competing interests declared.

Author contributions

Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft.

Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing - review and editing.

Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing - review and editing.

Ethics

Animal experimentation: This study was performed in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. All of the animals were handled according to approved institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) protocols (#2018-0124) of Texas A&M University.

Additional files

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and supporting files.

References

- Abelló G, Khatri S, Radosevic M, Scotting PJ, Giráldez F, Alsina B. Independent regulation of Sox3 and Lmx1b by FGF and BMP signaling influences the neurogenic and non-neurogenic domains in the chick otic placode. Developmental Biology. 2010;339:166–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agathocleous M, Love NK, Randlett O, Harris JJ, Liu J, Murray AJ, Harris WA. Metabolic differentiation in the embryonic retina. Nature Cell Biology. 2012;14:859–864. doi: 10.1038/ncb2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aït-Ali N, Fridlich R, Millet-Puel G, Clérin E, Delalande F, Jaillard C, Blond F, Perrocheau L, Reichman S, Byrne LC, Olivier-Bandini A, Bellalou J, Moyse E, Bouillaud F, Nicol X, Dalkara D, van Dorsselaer A, Sahel JA, Léveillard T. Rod-derived cone viability factor promotes cone survival by stimulating aerobic glycolysis. Cell. 2015;161:817–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsina B, Abelló G, Ulloa E, Henrique D, Pujades C, Giraldez F. FGF signaling is required for determination of otic neuroblasts in the chick embryo. Developmental Biology. 2004;267:119–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andermann P, Ungos J, Raible DW. Neurogenin1 defines zebrafish cranial sensory ganglia precursors. Developmental Biology. 2002;251:45–58. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann BM, Horos R, Fischer B, Castello A, Eichelbaum K, Alleaume AM, Schwarzl T, Curk T, Foehr S, Huber W, Krijgsveld J, Hentze MW. The RNA-binding proteomes from yeast to man Harbour conserved enigmRBPs. Nature Communications. 2015;6:10127. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermingham NA, Hassan BA, Price SD, Vollrath MA, Ben-Arie N, Eatock RA, Bellen HJ, Lysakowski A, Zoghbi HY. Math1: an essential gene for the generation of inner ear hair cells. Science. 1999;284:1837–1841. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermingham-McDonogh O, Stone JS, Reh TA, Rubel EW. FGFR3 expression during development and regeneration of the chick inner ear sensory epithelia. Developmental Biology. 2001;238:247–259. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botta A, Delteil F, Mettouchi A, Vieira A, Estrach S, Négroni L, Stefani C, Lemichez E, Meneguzzi G, Gagnoux-Palacios L. Confluence switch signaling regulates ECM composition and the plasmin proteolytic cascade in keratinocytes. Journal of Cell Science. 2012;125:4241–4252. doi: 10.1242/jcs.096289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LA, Amores A, Schilling TF, Jowett T, Baert JL, de Launoit Y, Sharrocks AD. Molecular characterization of the zebrafish PEA3 ETS-domain transcription factor. Oncogene. 1998;17:93–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulusu V, Prior N, Snaebjornsson MT, Kuehne A, Sonnen KF, Kress J, Stein F, Schultz C, Sauer U, Aulehla A. Spatiotemporal analysis of a glycolytic activity gradient linked to mouse embryo mesoderm development. Developmental Cell. 2017;40:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of Cancer cell metabolism. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2011;11:85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Johnson JE, Zoghbi HY, Segil N. The role of Math1 in inner ear development: uncoupling the establishment of the sensory primordium from hair cell fate determination. Development. 2002;129:2495–2505. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.10.2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico WJ. Protein release through nonlethal oncotic pores as an alternative nonclassical secretory pathway. BMC Cell Biology. 2011;12:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-12-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clem B, Telang S, Clem A, Yalcin A, Meier J, Simmons A, Rasku MA, Arumugam S, Dean WL, Eaton J, Lane A, Trent JO, Chesney J. Small-molecule inhibition of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase activity suppresses glycolytic flux and tumor growth. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2008;7:110–120. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esen E, Chen J, Karner CM, Okunade AL, Patterson BW, Long F. WNT-LRP5 signaling induces Warburg Effect through mTORC2 activation during osteoblast differentiation. Cell Metabolism. 2013;17:745–755. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farabegoli F, Vettraino M, Manerba M, Fiume L, Roberti M, Di Stefano G. Galloflavin, a new lactate dehydrogenase inhibitor, induces the death of human breast Cancer cells with different glycolytic attitude by affecting distinct signaling pathways. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2012;47:729–738. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Xu Q. Pivotal role of hmx2 and hmx3 in zebrafish inner ear and lateral line development. Developmental Biology. 2010;339:507–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SJ, Johnson JL, Smith MA, Jackson CL. Plasmin-mediated fibroblast growth factor-2 mobilisation supports smooth muscle cell proliferation in human saphenous vein. Journal of Vascular Research. 2001;38:492–501. doi: 10.1159/000051082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou Y, Vemaraju S, Sweet EM, Kwon HJ, Riley BB. sox2 and sox3 play unique roles in development of hair cells and neurons in the zebrafish inner ear. Developmental Biology. 2018;435:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W, Gaeta X, Sahakyan A, Chan AB, Hong CS, Kim R, Braas D, Plath K, Lowry WE, Christofk HR. Glycolytic metabolism plays a functional role in regulating human pluripotent stem cell state. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:476–490. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan KW, Ruiz-Echevarria MJ, Quan Y, Peltz SW. Characterization of cis-acting sequences and decay intermediates involved in nonsense-mediated mRNA turnover. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1995;15:809–823. doi: 10.1128/MCB.15.2.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halestrap AP. The mitochondrial pyruvate carrier kinetics and specificity for substrates and inhibitors. Biochemical Journal. 1975;148:85–96. doi: 10.1042/bj1480085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halestrap AP, Denton RM. Specific inhibition of pyruvate transport in rat liver mitochondria and human erythrocytes by alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamate. The Biochemical Journal. 1974;138:313–316. doi: 10.1042/bj1380313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins TA, Cavodeassi F, Erdélyi F, Szabó G, Lele Z. The small molecule Mek1/2 inhibitor U0126 disrupts the chordamesoderm to notochord transition in zebrafish. BMC Developmental Biology. 2008;8:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Cunningham D, Bermingham-McDonogh O. Loss of Fgfr3 leads to excess hair cell development in the mouse organ of corti. Developmental Dynamics. 2007;236:525–533. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Ray CA, Bermingham-McDonogh O. Fgf20 is required for sensory epithelial specification in the developing cochlea. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:5991–5999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1690-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho MY, Tang SJ, Ng WV, Yang W, Leu SJ, Lin YC, Feng CK, Sung JS, Sun KH. Nucleotide-binding domain of phosphoglycerate kinase 1 reduces tumor growth by suppressing COX-2 expression. Cancer Science. 2010;101:2411–2416. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacques BE, Montcouquiol ME, Layman EM, Lewandoski M, Kelley MW. Fgf8 induces pillar cell fate and regulates cellular patterning in the mammalian cochlea. Development. 2007;134:3021–3029. doi: 10.1242/dev.02874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Romero-Carvajal A, Haug JS, Seidel CW, Piotrowski T. Gene-expression analysis of hair cell regeneration in the zebrafish lateral line. PNAS. 2014;111:E1383–E1392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402898111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Y, Shiozawa Y, Wang J, Wang J, Wang Z, Pedersen EA, Lee CH, Hall CL, Hogg PJ, Krebsbach PH, Keller ET, Taichman RS. Expression of PGK1 by prostate Cancer cells induces bone formation. Molecular Cancer Research. 2009;7:1595–1604. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarci H, Edlund RK, Groves AK, Riley BB. Tfap2a promotes specification and maturation of neurons in the inner ear through modulation of bmp, fgf and notch signaling. PLOS Genetics. 2015;11:e1005037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarci H, Gerberding A, Riley BB. Spemann organizer gene goosecoid promotes delamination of neuroblasts from the otic vesicle. PNAS. 2016;113:E6840–E6848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609146113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M, Li J, Chuang JL, Chuang DT. Distinct structural mechanisms for inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoforms by AZD7545, dichloroacetate, and radicicol. Structure. 2007;15:992–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Developmental Dynamics. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korzh V, Sleptsova I, Liao J, He J, Gong Z. Expression of zebrafish bHLH genes ngn1 and nrd defines distinct stages of neural differentiation. Developmental Dynamics. 1998;213:92–104. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199809)213:1<92::AID-AJA9>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku YC, Renaud NA, Veile RA, Helms C, Voelker CC, Warchol ME, Lovett M. The transcriptome of utricle hair cell regeneration in the avian inner ear. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34:3523–3535. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2606-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassiter RN, Reynolds SB, Marin KD, Mayo TF, Stark MR. FGF signaling is essential for ophthalmic trigeminal placode cell delamination and differentiation. Developmental Dynamics. 2009;238:1073–1082. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay AJ, Jiang XM, Kisker O, Flynn E, Underwood A, Condron R, Hogg PJ. Phosphoglycerate kinase acts in tumour angiogenesis as a disulphide reductase. Nature. 2000;408:869–873. doi: 10.1038/35048596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. Fgf signaling instructs position-dependent growth rate during zebrafish fin regeneration. Development. 2005;132:5173–5183. doi: 10.1242/dev.02101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DC, Sohn HA, Park ZY, Oh S, Kang YK, Lee KM, Kang M, Jang YJ, Yang SJ, Hong YK, Noh H, Kim JA, Kim DJ, Bae KH, Kim DM, Chung SJ, Yoo HS, Yu DY, Park KC, Yeom YI. A lactate-induced response to hypoxia. Cell. 2015;161:595–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Castello A, Fischer B, Leicht S, Föehr S, Frese CK, Ragan C, Kurscheid S, Pagler E, Yang H, Krijgsveld J, Hentze MW, Preiss T. The cardiomyocyte RNA-Binding proteome: links to intermediary metabolism and heart disease. Cell Reports. 2016;16:1456–1469. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.06.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberti MV, Locasale JW. The Warburg Effect: how does it benefit Cancer cells? Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2016;41:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q, Chen Z, del Barco Barrantes I, de la Pompa JL, Anderson DJ. neurogenin1 is essential for the determination of neuronal precursors for proximal cranial sensory ganglia. Neuron. 1998;20:469–482. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80988-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magariños M, Aburto MR, Sánchez-Calderón H, Muñoz-Agudo C, Rapp UR, Varela-Nieto I. RAF kinase activity regulates neuroepithelial cell proliferation and neuronal progenitor cell differentiation during early inner ear development. PLOS ONE. 2010;5:e14435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier EC, Whitfield TT. RA and FGF signalling are required in the zebrafish otic vesicle to pattern and maintain ventral otic identities. PLOS Genetics. 2014;10:e1004858. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manerba M, Vettraino M, Fiume L, Di Stefano G, Sartini A, Giacomini E, Buonfiglio R, Roberti M, Recanatini M. Galloflavin (CAS 568-80-9): a novel inhibitor of lactate dehydrogenase. ChemMedChem. 2012;7:311–317. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour SL, Goddard JM, Capecchi MR. Mice homozygous for a targeted disruption of the proto-oncogene int-2 have developmental defects in the tail and inner ear. Development. 1993;117:13–28. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour SL, Twigg SR, Freeland RM, Wall SA, Li C, Wilkie AO. Hearing loss in a mouse model of muenke syndrome. Human Molecular Genetics. 2009;18:43–50. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maulding K, Padanad MS, Dong J, Riley BB. Mesodermal Fgf10b cooperates with other fibroblast growth factors during induction of otic and epibranchial placodes in zebrafish. Developmental Dynamics. 2014;243:1275–1285. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meddahi A, Lemdjabar H, Caruelle JP, Barritault D, Hornebeck W. Inhibition by dextran derivatives of FGF-2 plasmin-mediated degradation. Biochimie. 1995;77:703–706. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)88185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez-Montes I, Escobar B, Palacios B, Gómez MJ, Izquierdo-Garcia JL, Flores L, Jiménez-Borreguero LJ, Aragones J, Ruiz-Cabello J, Torres M, Martin-Puig S. Myocardial VHL-HIF signaling controls an embryonic metabolic switch essential for cardiac maturation. Developmental Cell. 2016;39:724–739. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millimaki BB, Sweet EM, Dhason MS, Riley BB. Zebrafish atoh1 genes: classic proneural activity in the inner ear and regulation by fgf and notch. Development. 2007;134:295–305. doi: 10.1242/dev.02734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millimaki BB, Sweet EM, Riley BB. Sox2 is required for maintenance and regeneration, but not initial development, of hair cells in the zebrafish inner ear. Developmental Biology. 2010;338:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero J-A, Kilian B, Chan J, Bayliss PE, Heisenberg C-P. Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase is required for process outgrowth and cell polarization of gastrulating mesendodermal cells. Current Biology. 2003;13:1279–1289. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00505-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechiporuk A, Linbo T, Raible DW. Endoderm-derived Fgf3 is necessary and sufficient for inducing neurogenesis in the epibranchial placodes in zebrafish. Development. 2005;132:3717–3730. doi: 10.1242/dev.01876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirenberg MW, Hogg JF. Inhibition of anaerobic glycolysis in ehrlich ascites tumor cells by 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose. Cancer Research. 1958;18:518–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hagan RC, Tozer RG, Symons M, McCormick F, Hassell JA. The activity of the ets transcription factor PEA3 is regulated by two distinct MAPK cascades. Oncogene. 1996;13:1323–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obholzer N, Swinburne IA, Schwab E, Nechiporuk AV, Nicolson T, Megason SG. Rapid positional cloning of zebrafish mutations by linkage and homozygosity mapping using whole-genome sequencing. Development. 2012;139:4280–4290. doi: 10.1242/dev.083931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oginuma M, Moncuquet P, Xiong F, Karoly E, Chal J, Guevorkian K, Pourquié O. A gradient of glycolytic activity coordinates FGF and wnt signaling during elongation of the body Axis in amniote embryos. Developmental Cell. 2017;40:342–353. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K, Kita T, Sato S, O'Neill P, Mak SS, Paschaki M, Ito M, Gotoh N, Kawakami K, Sasai Y, Ladher RK. FGFR1-Frs2/3 signalling maintains sensory progenitors during inner ear hair cell formation. PLOS Genetics. 2014;10:e1004118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbudak EM, Tassy O, Pourquié O. Spatiotemporal compartmentalization of key physiological processes during muscle precursor differentiation. PNAS. 2010;107:4224–4229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909375107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng M, Yin N, Chhangawala S, Xu K, Leslie CS, Li MO. Aerobic glycolysis promotes T helper 1 cell differentiation through an epigenetic mechanism. Science. 2016;354:481–484. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips BT, Bolding K, Riley BB. Zebrafish fgf3 and fgf8 encode redundant functions required for otic placode induction. Developmental Biology. 2001;235:351–365. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philp A, Macdonald AL, Watt PW. Lactate--a signal coordinating cell and systemic function. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2005;208:4561–4575. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirvola U, Spencer-Dene B, Xing-Qun L, Kettunen P, Thesleff I, Fritzsch B, Dickson C, Ylikoski J. FGF/FGFR-2(IIIb) signaling is essential for inner ear morphogenesis. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:6125–6134. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06125.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirvola U, Ylikoski J, Trokovic R, Hébert JM, McConnell SK, Partanen J. FGFR1 is required for the development of the auditory sensory epithelium. Neuron. 2002;35:671–680. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00824-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman AJ, Law MY, Chien CB. Pathfinding in a large vertebrate axon tract: isotypic interactions guide retinotectal axons at multiple choice points. Development. 2008;135:2865–2871. doi: 10.1242/dev.025049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puligilla C, Feng F, Ishikawa K, Bertuzzi S, Dabdoub A, Griffith AJ, Fritzsch B, Kelley MW. Disruption of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 signaling results in defects in cellular differentiation, neuronal patterning, and hearing impairment. Developmental Dynamics. 2007;236:1905–1917. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raft S, Koundakjian EJ, Quinones H, Jayasena CS, Goodrich LV, Johnson JE, Segil N, Groves AK. Cross-regulation of Ngn1 and Math1 coordinates the production of neurons and sensory hair cells during inner ear development. Development. 2007;134:4405–4415. doi: 10.1242/dev.009118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raible F, Brand M. Tight transcriptional control of the ETS domain factors erm and Pea3 by fgf signaling during early zebrafish development. Mechanisms of Development. 2001;107:105–117. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(01)00456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifers F, Böhli H, Walsh EC, Crossley PH, Stainier DY, Brand M. Fgf8 is mutated in the zebrafish acereballar (ace) mutans and is required for maintenance of midbrain-hindbraion boundary development and somitogenesis. Development. 1998;125:2381–2395. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.13.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley BB, Grunwald DJ. Efficient induction of point mutations allowing recovery of specific locus mutations in zebrafish. PNAS. 1995;92:5997–6001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehl H, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Zebrafish pea3 and erm are general targets of FGF8 signaling. Current Biology. 2001;11:503–507. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]