Abstract

Purpose

To systematically review published research exploring workplace discrimination toward physicians of color with a focus on discrimination from patients.

Method

The authors searched PubMed, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Scopus, Academic Search Premier, and Web of Science from 1990 through 2017 and performed supplemental manual bibliographic searches. Eligible studies were in English and assessed workplace discrimination experienced by physicians of color practicing in the U.S. including physicians from ethnic/racial groups underrepresented in medicine, Asians, and international medical graduates. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts, 3 reviewers read the full text of eligible studies, and 2 reviewers extracted data and appraised quality using Joanna Briggs Institute checklist for qualitative research or the AXIS tool for quality of cross-sectional studies.

Results

Of the 19 eligible studies, 6 conducted surveys and 13 analyzed data from interviews and/or focus groups; most were medium quality. All provided evidence to support the high prevalence of workplace discrimination experienced by physicians of color, particularly black physicians and women of color. Discrimination was associated with adverse effects on career, work environment, and health. In the few studies inquiring about patient interactions, discrimination was predominantly refusal of care. No study evaluated an intervention to reduce workplace discrimination experienced by physicians of color. Ethnic/racial groups were inconsistent across studies, and some samples included physicians in Canada, non-physician faculty, or trainees.

Conclusion

With physicians of color comprising a growing percentage of the U.S. physician workforce, healthcare organizations must examine and implement effective ways to ensure a healthy and supportive work environment.

Keywords: Workplace discrimination, bias, physician

1. Introduction

Increasing the ethnic and racial diversity of the physician workforce has many benefits. A more diverse research team enhances productivity, creativity, and critical analysis;1–6 teaching and mentorship practices are more innovative and inclusive when informed by diverse perspectives;7,8 and greater ethnic and racial diversity in the physician workforce advances health equity.9–12 Physicians of color comprise a growing proportion of the U.S. physician workforce in which approximately 48.5% identify as white, 12.5% as Asian, 4.2% as black or African American, 4.6% as Hispanic or Latino, 0.4% as American Indian or Alaskan Native, and 0.4% as other race (with 29.4% unknown).13 Approximately 22.7% are international medical graduates (IMGs)14 of whom the majority completed their medical education in countries without predominantly European heritage: 23% in India, 17% in the Caribbean, 6% in the Philippines, 6% in Pakistan, and 5% in Mexico.14

The National Academy of Medicine15 states that “overt and unconscious bias” influences the relationship between clinician well-being, clinician-patient interactions, and patient well-being. Our goal was to identify and synthesize published research on workplace discrimination experienced by physicians of color practicing in the U.S., especially research on discrimination from patients16–18 in light of the growing visibility of this occurrence.16,19–24

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data sources and searches

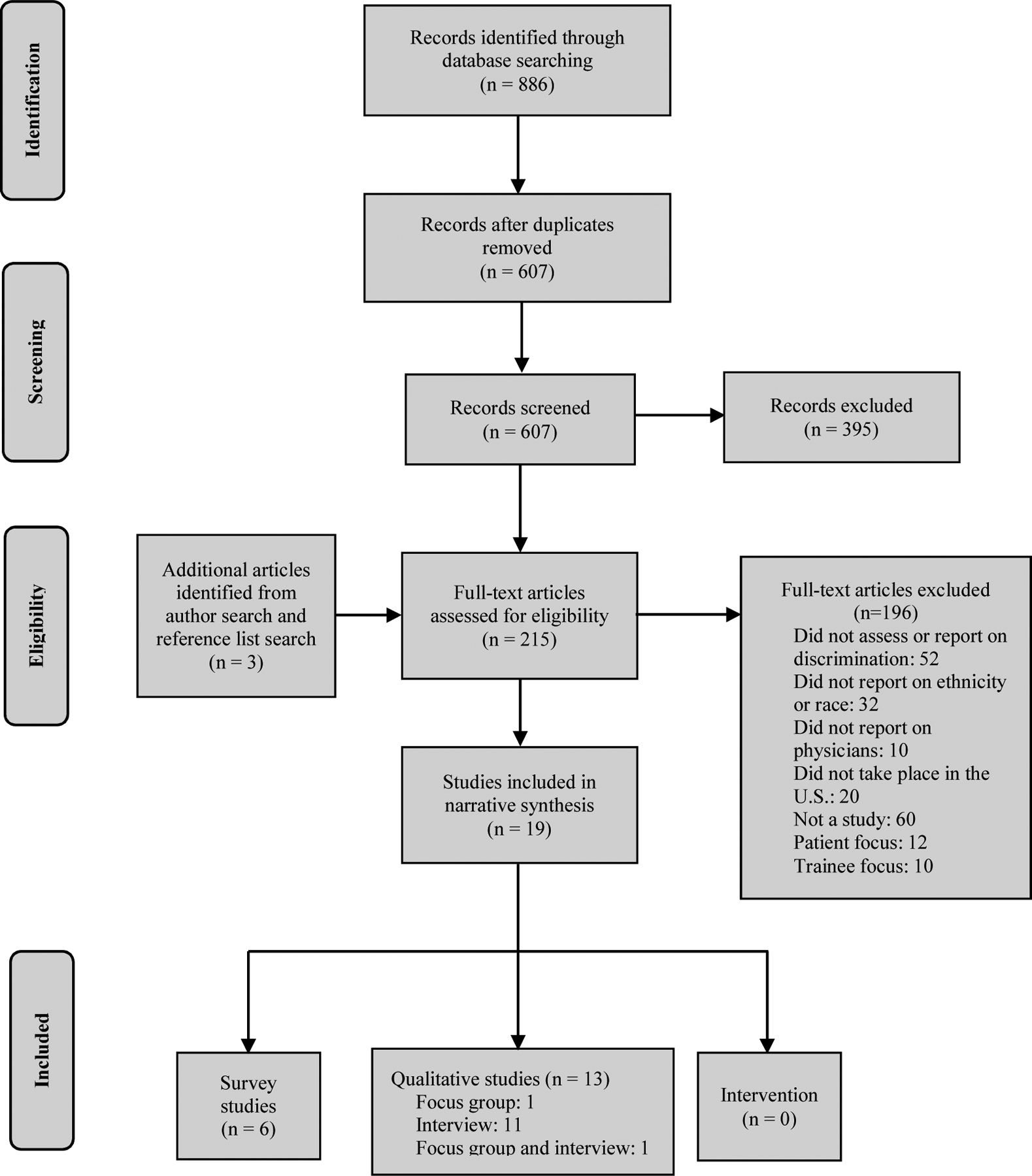

We electronically searched PubMed, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Scopus, Academic Search Premier, and Web of Science for studies published between 1990 and 2017. We chose 1990 as the initial date because enrollment of medical students from ethnic and racial minority groups underrepresented in medicine reached 10% in that year and it marked a time when the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) redoubled efforts to increase medical student ethnic/racial diversity.25 The search terms for each database were: (Bias OR prejudice OR perception OR discrimination OR “attitude toward” OR diversity) AND (faculty OR physician OR doctor) AND (Minority OR minorities OR ethnic OR race OR racial OR gender OR non-White) AND (“academic medicine” OR “medical school” OR “medical schools” OR “health profession”) NOT (student OR patient). Results from all databases were exported and uploaded to the electronic reference manager software program, EndNote.26 Duplicates were removed. The final list of studies was exported to Microsoft Excel. We manually examined and retrieved selected studies from the bibliographies of electronically identified studies and performed supplemental Google Scholar searches of the first author, reviewing any relevant studies published between 1990 and 2017. We defined physicians of color as physicians who identify as members of an ethnic or racial group underrepresented in the medical profession (URM) relative to their proportions in the U.S. population (black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or Hispanic/Latino);27,28 physicians of Asian descent; and physicians who trained in countries without predominantly European heritage. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Figure 1).29

Figure 1.

Results of literature search in PubMed, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Scopus, Academic Search Premier, and Web of Science

2.2. Study selection

We included studies written in English and conducted in the U.S. that collected data from practicing physicians on workplace discrimination based on ethnicity or race. We excluded studies of physicians-in-training (medical students, residents, or fellows), opinion pieces, commentaries, and editorials.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers independently analyzed all titles and abstracts, eliminating those that did not meet the inclusion requirements. Three reviewers independently examined the full text of the remaining studies with the senior investigator adjudicating uncertainties. Two reviewers extracted data from the final set of studies assessing quality with either the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist for qualitative research or the AXIS tool for quality of cross-sectional studies.30,31

2.4. Data synthesis and analysis

The range of study designs, participant populations, analytical methods, and the absence of any intervention precluded a meta-analysis of quantitative findings or a meta-ethnography of qualitative studies.32–34 We therefore conducted a narrative synthesis using tabulation and descriptive analysis to summarize findings and examine similarities and differences across studies, specifically probing for data on physicians’ interactions with patients.35 We contextualized survey results with data from qualitative studies and interpreted our overall findings in the context of the larger body of research on workplace discrimination.

3. Results and Discussion

After removal of duplicates, our search retrieved 607 studies published between 1990 and 2017. We excluded 395 studies after reviewing titles and abstracts and conducted full-text reviews of the remaining 215 studies, excluding 196 for reasons outlined in Figure 1. Manual bibliographic and author searches identified an additional 3 studies. The final data set consisted of 19 studies that reported on ethnic or racial discrimination experienced by physicians of color who practice in the U.S.

3.1. Study characteristics

Of these 19 studies, 13 reported results from interviews36–47 and/or focus groups,43,48 with the remaining 6 containing results from surveys (Table 1).49–54 In 3 cases, the same sample gave rise to two studies.37,38,41,42,51,52 Eight studies (on 6 samples) examined the experiences of URM physicians.39,41,42,45,46,48,51,52 Two studies (on 1 sample) exclusively examined IMG physicians,37,38 and 2 studies reported results for IMGs as a subgroup.53,54 Eight studies included white physicians but reported data separately,43,44,47,49,51–54 7 included only physicians of color,36,39–42,45,46 and 3 combined data from white physicians with data from physicians of color.37,38,48 Asians were grouped with whites as non-URM in 2 studies,43,49 with URM in 2 studies,40,45 and with Pacific Islanders and Hispanic Americans other than Mexican or Puerto Rican in 1 study.50 Ten studies were limited to faculty in academic medicine39,40,43–50 and 9 included physicians practicing in any setting.36–38,41,42,51–54 Two studies were conducted at a single institution,40,43 6 studies on regional samples,36–38,41,42,54 and 11 studies on national samples.39,44–53 Three studies included only women,39,44,53 and 4 studies focused on the experiences of a single ethnic or racial group: Indian, Native American, or of African descent.36,39,41,42 Only 5 studies were of high quality.36,38,39,42,46 The primary deficiencies of survey studies were the absence of sample size justification, data on non-responders, and mention of ethical approval.31 The primary deficiencies of the interview and focus group studies were incomplete descriptions of participants or methods and no discussion of the researchers’ backgrounds or their potential influence on the research.55

Table 1:

Study characteristics and findings

| Survays | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study, Year | Study details1 | Findings2 | Quality: deficiencies | Inquired about patient interaction | Patient interaction emerged on its own |

| Coombs and King, 200554 |

|

24.0% response rate:

|

Low:

|

Asked, “How often do you feel discriminated against by the following groups?” with patients as a group:

|

N/A |

| Corbie-Smith et al, 199953 |

|

58.5% response rate:

|

Low:

|

No | No |

| Nunez-Smith et al., 2009a51 |

|

46.6% response rate:

|

Medium:

|

Asked if patients have refused their care: percentage agreeing or strongly agreeing

|

N/A |

| Nunez-Smith et al., 2009b52 |

|

46.6% response rate:

|

Medium:

|

No | No |

| Peterson et al., 200450 |

|

60.0% response rate:

|

Medium:

|

No | No |

| Pololi et al., 201349 |

|

52.0% response rate:

|

Medium:

|

No | No |

| Focus Group or Focus Group and Interview | |||||

| Study, Year | Study details1 | Findings2 | Quality | Inquired about patient interaction | Patient interaction emerged on its own |

| Flores et al., 201648 |

|

|

Low:

|

No | In response to a general request to describe experiences with discrimination, one participant described a situation where a mother of a patient said, “I don’t want to be treated by a Mexican doctor.” |

| Price et al., 200543 |

|

|

Medium:

|

No | No |

| Interview | |||||

| Study, Year | Study details1 | Findings2 | Quality | Inquired about patient interaction | Patient interaction emerged on its own |

| Bhatt, 201336 |

|

|

High | Physicians of Indian descent asked if they had been discriminated against by patients because of ethnicity/race:

|

N/A |

| Carr et al., 200745 |

|

|

Medium:

|

No | No |

| Chen et al., 201038 |

|

|

High | Asked how “professional relationships” including with patients are affected by IMG status:

|

N/A |

| Chen et al., 201137 |

|

|

Medium-high:

|

Same question as Chen et al. 2010:

|

N/A |

| Elliott et al., 201039 |

|

|

High | No |

|

| Hassouneh et al., 201446 |

|

|

High | No | Two physicians of color shared their ability to connect with diverse patient population |

| Mahoney et al., 200840 |

|

|

Medium-high:

|

No | No |

| Nunez-Smith et al., 200742 |

|

|

High | No |

|

| Nunez-Smith et al., 200841 |

|

|

Medium-high

|

No | A participant brought up patients’ level of comfort interacting with a black physician “Many of our colleagues aren’t comfortable working with people from different backgrounds, be it patients or colleagues…” |

| Pololi et al., 201047 |

|

|

Medium

|

No | A participant shared their desire to provide care to patients and give back to their community |

| Pololi and Jones, 201044 |

|

|

Medium-high:

|

No | No |

The Study details column gives ethnicity/race information as described in each study.

The Findings column makes some assumptions for brevity and consistency: black refers to non-Hispanic black or African American; Hispanic/Latino is not limited to individuals with Mexican and Puerto Rican Heritage; Asian refers to the predominant group in a category.

N/A = not applicable; IMG = International Medical Graduate; USMG = United States Medical Graduate; AMA = American Medical Association; NMA = National Medical Association; POCs = Physicians of Color; URM = Underrepresented ethnic/racial group in medicine relative to percentage in the U.S. population (black or African American, Hispanic/Latino, American Indian or Alaska Native, or Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander

3.2. Prevalence and types of discrimination

Survey results confirmed the high prevalence of discrimination toward physicians of color and qualitative studies were replete with personal anecdotes of subtle and overt discrimination. In studies that included different ethnic/racial groups, black physicians consistently encountered discrimination at higher rates than any other group. In surveys that disaggregated responses by ethnic/racial group, workplace discrimination was reported by 59–71% of blacks,51–53 20–27% of Hispanics/Latinos,51–53 31–50% of Asians,50–53 6–29% of whites,50–53 and 35–63% of those who identified as other race.51,52 Compared to U.S.-born physicians, Corbie-Smith et al. found twice as much discrimination reported by those born in other countries and 45% of IMGs reported discrimination in the past 12 months;53 however, Nunez-Smith et al. found no difference in ethnic/racial discrimination or any type of discrimination reported by physicians born in or outside the U.S.51 Two studies compared reports of ethnic/racial discrimination in different practice sites: Coombs and King found higher rates in academic settings (246/455, 54%) than in solo practice (128/455, 28.1%),54 and Nunez-Smith et al. found rates of 16–42% across all practice settings with no significant difference.51 Qualitative studies provided detailed examples of discrimination experienced by physicians of color and descriptions of feeling isolated, alone, invisible, and treated like an outsider.37,40–48 Many shared examples of overtly prejudiced statements or conscious discriminatory acts stated outright by the offender to be race- or gender-based.36–38,41–44,47,48 More frequent, however, were subtle practices of discrimination in the form of inadequate institutional support, exclusion from social networks, devaluation of research on minority health or health disparities, and a lack of institutional commitment to advancing diversity.40,43,44,46,47 Physicians of color described facing greater scrutiny, being held to higher standards, having their competence questioned, needing to justify their credentials,43,45–47,50–52 and being mistaken for maintenance, housekeeping, or food service workers in the workplace.42,47 Examples of effective mentors were given, but participants also reported a relative lack of mentors, role models, and social capital at their institution.40–43,45–47 Some found themselves being pressured into diversity-related roles, serving as “window dressing,” and being “used by the institution” as the token minority.40–42,46,48 Poor recruitment and promotion practices also contributed to experiences of discrimination by faculty of color.36,40,43,45–48,50 In spite of frequent and persistent experiences with race-based discrimination, participants described the silence of others in their institution around race generally and around their experiences of discrimination specifically, in conjunction with an inability to raise the issue themselves for fear of repercussions.42,44,45,49,54 These fears may be justified as Coombs and King, the only study to ask about reporting episodes of discrimination and the institutional response, found of the 50 respondents who made a formal complaint of discrimination, 50% reported no change and almost 20% reported worsening of the situation.54 Among physicians of color, 62.5% (105/168) were more likely to report no change in their situation when they filed a complaint about discrimination compared to 37.5% (109/277) of white physicians54.

Four studies identified language or accent as a source of discrimination for physicians of color.36,43,47,50 In their survey of medical school faculty, Peterson et al. found that those with a primary language other than English had almost twice the odds of experiencing ethnic/racial bias than those whose primary language was English.50 In qualitative studies, 1 URM male physician shared how he has had his medical decisions questioned because of his accent43, and a white physician shared his own prejudice against others with certain language patterns.47 IMGs reported encountering limitations in location of practice, choice of specialty, and opportunities for advancement38 and indicated that the discrimination they faced varied depending on where they are from, with European countries and Canada being more respected than other locations.36,42

3.3. Interactions with patients

Only 1 of the 6 survey studies specifically asked about discrimination from patients. In that study of 529 physicians, significantly more black (60%) than any other ethnic/racial group agreed or strongly agreed that “patients have refused my care.”51 A second survey study included patients among possible sources of discrimination and found 18.4% of female (38/206) and 14.1% of male (44/239) physicians reported such discrimination frequently or occasionally, but the results were not broken down by ethnic/racial group in a sample of 445 physicians where 57.7% of respondents were white.54 No qualitative study of URM physicians specifically asked about interactions with patients. The 3 qualitative studies that did inquire about patient interactions did not include URM physicians.36–38 One of these studies interviewed physicians of Indian descent and found that 65% of 50 first-generation and 57% of 30 second-generation physicians reported discrimination from patients.36 The other 2 studies reported on the same sample of IMG physicians.37,38 In these, Chen and colleagues asked about the impact of being an IMG on “professional relationships” including patients.37,38 Interviewees noted that they had to adjust to different physician-patient dynamics in the U.S. compared to the country in which they trained but felt accepted by their patients as “a good doctor,”38 often able to empathize with patients from marginalized groups, and able to bring important skills from their medical experiences in other countries.37 Statements about patient interactions emerged in an additional 6 qualitative studies.39,41,42,44,46,48 In addition to statements about patients’ refusal of care and mistrust39,41,42,48, several physicians of color reflected on positive aspects of their ethnic/racial identity in patient interactions in feeling they were giving back to their community and able to connect with or advocate for patients from marginalized groups.39,42,46

3.4. Intersecting identities

The intersection of gender-based and ethnic/racial-based discrimination was documented in both survey and qualitative studies with women of color experiencing what Bhatt referred to as “gendered racism.”36 Nunez-Smith et al. found significantly more black female (11/29, 37.9%) than white female (12/74, 16.2%) or black male (12/48, 25.0%) physicians reported at least 1 job turnover as a result of discrimination.52 Coombs and King found female physicians were significantly more likely than male physicians to have experienced at least one form of discrimination in the past 12 months (98/191, 51.3% vs. 79/254, 31.2%) but did not report data for physicians of color separately.54 Although lacking a male comparison group, in a sample of over 4000 female physicians, Corbie-Smith et al. found that 62% of women who identified as black (78/125), 36% as other race (44/121), 31% as Asian (211/681), and 20% as Hispanic (34/169) reported discrimination compared to 6% of white women (192/3192).53 Qualitative studies provide personal examples of experiences as a “double minority” as a physician of color and a female physician and how it resulted in increased feelings of isolation.43,44,46,47 Physicians of Indian descent discussed the double bind of gender and race, as well as the triple bind of gender, race, and being first-generation.36

3.5. Impact of discrimination

Seven of the 19 studies (4 qualitative and 3 survey) reported on the impact of workplace discrimination.42,43,47,48,50,52,53 In 2 surveys, employment-related effects included greater likelihood of changing specialty, wishing they had not chosen medicine, job turnover, or leaving medicine.51,53 Discrimination was also associated with negative effects on career advancement, lower career satisfaction, and feeling unwelcome at an institution in qualitative studies.36,37,41–44,46–48 Four studies described the cumulative burden imposed by discrimination on physicians of color,42,43,46,48 which Hassouneh et al. referred to as a “minority tax”46 and Nunez-Smith et al. defined as “racial fatigue.”42 Nunez-Smith et al. was the only study to examine the association of experiencing workplace discrimination with self-rated health. In their national sample of 529 practicing physicians, of the 18 who rated their health as fair/poor 12 (65%) had experienced discrimination, and of the 227 who rated their heath as excellent 62 (27%) reported discrimination of any type.51

3.6. Importance of organizational support and workplace climate

Multiple physicians of color in 9 of the 13 qualitative studies reported on the importance of having both personal and organizational support to buffer the negative impact of discrimination.37,39–41,43,45–48 Physicians of color described the importance of family members and friends outside the institution as important sources of support,42,45 and because of concern about discussing workplace discrimination at their own institution they also described the need to seek support from physicians or colleagues elsewhere.41,42,48 In terms of organizational support, Nunez-Smith et al. found that compared to their white colleagues physicians of color were less comfortable reporting discrimination at their institution, less comfortable discussing ethnicity/race at work, and did not feel that issues of discrimination were discussed at work;51 and Peterson et al. found that faculty who experienced ethnic/racial discrimination were less likely to “feel welcomed” at their institution.50 In interviews with “minority faculty” that included African Americans, Asians/Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics/Latinos at University of California San Francisco, there was a feeling that increasing diversity was not an institutional priority.40 In interview studies exploring the experiences of physicians of African descent, some participants shared the need to leave an institution due to lack of organizational support41 related to ethnicity and race and the negative affect this lack of support had on workplace climate.42 According to one URM faculty member in an interview study by Pololi et al., the culture of academic medicine with its focus on the individual can contribute to the perception of a negative and unsupportive workplace climate for Latino and American Indian faculty who may come from cultures centered around family and community.47 In a study of faculty at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine conducted by Price et al., participants shared how ethnic/racial bias contributes to a negative “diversity climate” in a number of ways.43 Four studies identified mentors as sources of support,37,39,40,43 with 7 studies finding that physicians of color sometimes find social support from selected colleagues and other physicians of color in their workplace, but often needed to find such support outside their institution.37,40–43,45,48

3.7. Discussion

This systematic review confirms that physicians of color practicing in the U.S. frequently experience overt and subtle workplace discrimination from leadership, colleagues, and patients. Experiencing discrimination is associated with negative career outcomes and creates an unwelcoming work environment with a culture of silence around experiences of discrimination; pressure to take on diversity-related tasks; and feelings of isolation, fatigue, hurt, and invisibility.

Although examples of overt discrimination were plentiful, many of the experiences fall in the realm of microaggressions.56,57 The daily workplace experiences of microaggressions and incivility in interpersonal interactions, inequities in promotion, and biases in performance review for nonwhite employees are well documented.56,58,59 As with physicians, these experiences are associated with greater job dissatisfaction and intention to leave,60,61 and as in the study by Nunez-Smith et al.,51 perceived discrimination in the workplace has been associated with adverse health outcomes.61–64

There was almost no attempt to collect data on patient interactions despite the centrality of patient care in physicians’ lives. The lack of curiosity regarding experiences of physicians of color with discrimination from patients may reflect underlying assumptions that these physicians care solely or predominantly for patients of color which have their roots in U.S. history. In 1910, recommendations from Flexner report set the stage for comprehensive reform of medical education in the U.S. and Canada.65 This report explicitly stated that the practice of black physicians “will be limited to his own race…” Unfortunately, contemporary arguments for increasing the ethnic and racial diversity of the physician workforce continue to focus narrowly on benefits to ethnic/racial minority and underserved populations.10,66 While inarguably important for health equity,10,66–69 this singular focus reinforces Flexner’s original circumscribed patient practice for physicians of color (at least for black physicians), diminishes or ignores the broader scope of benefits of a diverse physician workforce, and may underlie the failure to examine race-based discrimination from patients toward physicians of color in the research we reviewed.10

Asian physicians are sometimes grouped with white physicians because their percentage in the U.S. physician workforce exceeds their percentage of the overall U.S. population. Such grouping does Asians a disservice because Asian physicians experienced more discrimination than white physicians51 and had negative employment outcomes similar to URM physicians.52

One of the reasons patient discrimination toward physicians of color is increasingly visible if not more common23,24,70–74 may be the 2010 Affordable Care Act’s edict to tie healthcare organization payment to patient satisfaction through the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Health Care Providers and Systems scores. Emboldened as consumers, patients may feel entitled to express personal biases toward physicians of color;73–75 and focused on the bottom line, healthcare organizations may tolerate such discriminatory behaviors.24 In a national survey of over 800 physicians, WebMD found that 60% of respondents had received offensive remarks from patients about some personal characteristic and almost half had a patient request a different physician.16,74 Healthcare systems have faced no legal challenges for failing to protect physicians from patients’ discriminatory remarks or refusal of care based on some personal characteristic (gender, ethnicity, race, religion, weight).24

Although the American Medical Association’s code of ethics states that physicians can “terminate the patient-physician relationship with a patient who uses derogatory language or acts in a prejudicial manner,”76 physicians would likely be penalized in patient satisfaction scores for doing so. Physicians have little legal protection from discrimination by patients. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 protects patients from discriminatory practices in the provision of healthcare services but does not protect physicians of color from discrimination by patients. Title II of this Act outlaws discrimination in public accommodations but does not name hospitals or clinics as public accommodations. Title VII protects employees from discrimination, but physicians are not generally employed by the hospital or clinic in which they practice. If healthcare organizations tie physician reimbursement to patient satisfaction scores and physicians of color systematically receive lower scores from their white patients than their comparable nonwhite patients,75 there might be grounds for legal action under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act which prohibits discrimination in activities and programs that receive federal funding.77

Healthcare organizations must develop policies and practices that support their increasingly diverse physician workforce from discrimination from all sources, including patients. The only study in this review to survey experiences with reporting an incident of discrimination suggests that current policies may be ineffective and potentially harmful, but the authors provided no specific examples of the type of harm incurred by those who reported experiencing discrimination.54 Over half of physicians in this study who reported an incident of discrimination were unsatisfied with the organization’s response.54 Nevertheless, the importance of organizational support and a supportive workplace climate described by some physicians of color in buffering the negative effects of discrimination is confirmed by other research. For example, Miner at al. confirmed in 2 studies that the negative employment and health outcomes of workplace incivility were buffered by organizational support defined as a belief that the organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being.61 A longitudinal study by Sheridan et al. of science and medicine faculty suggests that fostering such a positive workplace climate would have many benefits within academic medicine.78 They found that all faculty, including faculty of color, who experienced a more positive department climate published more papers and received more grants.79 O’Brien et al. similarly found that faculty in science and engineering who experienced discrimination had lower academic productivity over time62 and that supervisor support mitigated the negative impact of discrimination. We have previously shown that improving department climate had positive long-term effects on hiring and retention.80–82

3.8. Limitations

Our search strategy excluded grey literature research and studies published before 1990. Our criteria were limited to practicing physicians of color in the U.S., but 2 studies included physicians from Canada,51,52 3 included non-MD faculty,44,45,49 2 did not indicate IMGs’ country of origin,43,46 and 1 included physicians-in-training.36 Ethnic and racial grouping was inconsistent across some studies, particularly for Asians. None of the cohort studies were longitudinal so the directionality of the association between experiencing discrimination, health, and some employment outcomes cannot be ascertained.

4. Implications

Our review suggests multiple directions for future research beginning with an assessment of healthcare organizations’ current policies to protect physicians of color from discrimination with data on their effectiveness. Also needed is exploration of legal recourse for physicians of color if healthcare organizations tie their pay to patient satisfaction scores and if this systematically results in lower pay for physicians of color than their white counterparts. The existence of daily workplace indignities experienced by physicians of color needs no further evidence. It is time to develop interventions informed by existing research and test their effectiveness on reducing workplace discrimination towards physicians of color from leaders, colleagues, and patients; enhancing perceptions of workplace climate; and improving employment outcomes. As stated by the National Academy of Medicine, reducing the negative impact of cultural stereotypes in physician-patient interactions will benefit both the patient and the physician.15

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Mary Hitchcock, Health Sciences Librarian at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Funding/Support

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers UL1TR000427, TL1TR000429, and TL1TR002375; R35GM122557] and the University of Wisconsin Department of Medicine.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interest: None.

Contributor Information

Amarette Filut, Center for Women’s Health Research, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin..

Madelyn Alvarez, Women’s Health Medical Director, William S. Middleton VA Hospital, Director, VA Advanced Fellowship in Women’s Health National Coordinating Center, master’s candidate, Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis at University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Education, Madison, WI..

Molly Carnes, Departments of Medicine, Psychiatry, and Industrial & Systems Engineering and Director, Center for Women’s Health Research, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin..

References

- 1.Phillips KW, Medin D, Lee CD, Bang M, Bishop S, Lee D. How diversity works. Sci Am. 2014;311(4):42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kets W, Sandroni A. Challenging conformity: A case for diversity. 2016.

- 3.Page SE. The diversity bonus: How great teams pay off in the knowledge economy. Vol 2: Princeton University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woolley AW, Chabris CF, Pentland A, Hashmi N, Malone TW. Evidence for a collective intelligence factor in the performance of human groups. Science. 2010;330(6004):686–688. 10.1126/science.1193147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nielsen MW, Andersen JP, Schiebinger L, Schneider JW. One and a half million medical papers reveal a link between author gender and attention to gender and sex analysis. Nat Hum Behav. 2017;1(11):791 10.1038/s41562-017-0235-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman RB H W. Collaborating with people like me: Ethnic coauthorship within the United States. J Labor Econ. 2015;33(S1, Part 2):S289–S318. 10.3386/w19905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrison E, Grbic D. Dimensions of diversity and perception of having learned from individuals from different backgrounds: the particular importance of racial diversity. Acad Med. 2015;90(7):937–945. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Umbach PD. The contribution of faculty of color to undergraduate education. Res High Educ. 2006;47(3):317–345. 10.1007/s11162-005-9391-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levine CS, Ambady N. The role of non-verbal behaviour in racial disparities in health care: Implications and solutions. Med Educ. 2013;47(9):867–876. 10.1111/medu.12216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce. Missing persons: Minorities in the health professions. In: Washington DC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smedley BD, Butler AS, Bristow LR. In the nation’s compelling interest: Ensuring diversity in the health care workforce. National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson AR, Stith AY, Smedley BD. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nivet M, Castillo-Page L. Diversity in the physician workforce: facts & figures 2014.

- 14.Young A, Chaudhry HJ, Pei X, Arnhart K, Dugan M, Snyder GB. A census of actively licensed physicians in the United States, 2016. J Med Regul. 2017;103(2):7–21. 10.30770/2572-1852-99.2.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brigham T, Barden C, Dopp AL, et al. A Journey to Construct an All-Encompassing Conceptual Model of Factors Affecting Clinician Well-Being and Resilience. NAM Perspectives, Discussion Paper. National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC: https://nam.edu/journey-construct-encompassing-conceptualmodel-factors-affecting-clinician-well-resilience/. Published January 28, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tedeschi B 6 in 10 doctors report abusive remarks from patients, and many get little help coping with the wounds. Stat. 2017. https://www.statnews.com/2017/10/18/patient-prejudice-wounds-doctors/. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynolds KL, Cowden JD, Brosco JP, Lantos JD. When a family requests a white doctor. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):381–386. 10.1542/peds.2014-2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain SH. The racist patient. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(8):632–632. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reddy S How doctors deal with racist patients. The Wall Street Journal. 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-doctors-deal-with-racist-patients-1516633710. Published January 22, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novick DR. Racist patients often leave doctors at a loss. The Washington Post. 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/racist-patients-often-leave-doctors-at-a-loss/2017/10/19/9e9a2c46-9d55-11e7-9c8d-cf053ff30921_story.html?utm_term=.ad2cd993f3a4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J When the patient is a racist. The Health Care Blog. 2017. http://thehealthcareblog.com/blog/2017/04/08/when-the-patient-is-a-racist/. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rakatansky H Addressing patient biases toward physicians. R I Med J. 2017;100(12):11–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haelle T Physician guidance for dealing with racist patients. Medscape. 2016. https://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/859354. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paul-Emile K, Smith AK, Lo B, Fernandez A. Dealing with racist patients. New Engl J Med. 2016;374(8):708–711. 10.1056/NEJMp1514939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersdorf RG. Not a choice, an obligation. Acad Med. 1992;67(2):73–79. 10.1097/00001888-199202000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.EndNote X8 [computer program]. 2016.

- 27.United States Census Bureau. About Race. United States Census Bureau; https://www.census.gov/topics/population/race/about.html. Published 2018. Updated January 23, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The status of the new AAMC definition of “underrepresented in medicine” following the Supreme Court’s decision in Grutter. In: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):179–187. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e011458 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egger M, Smith GD, Phillips AN. Meta-analysis: principles and procedures. BMJ. 1997;315(7121):1533–1537. 10.1136/bmj.315.7121.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doyle LH. Synthesis through meta-ethnography: paradoxes, enhancements, and possibilities. Qual Res. 2003;3(3):321–344. [Google Scholar]

- 34.France EF, Ring N, Thomas R, Noyes J, Maxwell M, Jepson R. A methodological systematic review of what’s wrong with meta-ethnography reporting. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):119 10.1177/1468794103033003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme. 2006;1:b92. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhatt W The little brown woman: Gender discrimination in American medicine. Gend Soc F. 2013;27(5):659–680. 10.1177/0891243213491140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen PG-C, Curry LA, Bernheim SM, Berg D, Gozu A, Nunez-Smith M. Professional challenges of non-US-born international medical graduates and recommendations for support during residency training. Acad Med. 2011;86(11):1383 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823035e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen PGC, Nunez-Smith M, Bernheim SM, Berg D, Gozu A, Curry LA. Professional experiences of international medical graduates practicing primary care in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(9):947–953. 10.1007/s11606-010-1401-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elliott BA, Dorscher J, Wirta A, Hill DL. Staying connected: Native American women faculty members on experiencing success. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):675–679. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d28101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahoney MR, Wilson E, Odom KL, Flowers L, Adler SR. Minority faculty voices on diversity in academic medicine: perspectives from one school. Acad Med. 2008;83(8):781–786. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31817ec002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nunez-Smith M, Curry LA, Berg D, Krumholz HM, Bradley EH. Healthcare workplace conversations on race and the perspectives of physicians of African descent. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1471–1476. 10.1007/s11606-008-0709-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nunez-Smith M, Curry LA, Bigby J, Berg D, Krumholz HM, Bradley EH. Impact of race on the professional lives of physicians of African descent. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(1):45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Price EG, Gozu A, Kern DE, et al. The role of cultural diversity climate in recruitment, promotion, and retention of faculty in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):565–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pololi LH, Jones SJ. Women faculty: An analysis of their experiences in academic medicine and their coping strategies. Gender Med. 2010;7(5):438–450. 10.1016/j.genm.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carr PL, Palepu A, Szalacha L, Caswell C, Inui T. ‘Flying below the radar’: a qualitative study of minority experience and management of discrimination in academic medicine. Med Educ. 2007;41(6):601–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hassouneh D, Lutz KF, Beckett AK, Junkins EP Jr, Horton LL. The experiences of underrepresented minority faculty in schools of medicine. Med Edu Online. 2014;19(1):24768 10.3402/meo.v19.24768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pololi L, Cooper L, Carr P, Cooper LA. Race, disadvantage and faculty experiences in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(12):1363–1369. 10.1007/s11606-010-1478-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flores G, Mendoza FS, Fuentes-Afflick E, et al. Hot topics, urgent priorities, and ensuring success for racial/ethnic minority young investigators in academic pediatrics. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):201 10.1186/s12939-016-0494-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pololi LH, Evans AT, Gibbs BK, Krupat E, Brennan RT, Civian JT. The experience of minority faculty who are underrepresented in medicine, at 26 representative U.S. Medical Schools. Acad Med. 2013;88(9):1308–1314. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829eefff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peterson NB, Friedman RH, Ash AS, Franco S, Carr PL. Faculty self-reported experience with racial and ethnic discrimination in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(3):259–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nunez-Smith M, Pilgrim N, Wynia M, et al. Race/ethnicity and workplace discrimination: Results of a national survey of physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(11):1198–1204. 10.1007/s11606-009-1103-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nunez-Smith M, Pilgrim N, Wynia M, et al. Health care workplace discrimination and physician turnover. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(12):1274–1282. 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31139-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Corbie-Smith G, Frank E, Nickens HW, Elon L. Prevalences and correlates of ethnic harassment in the US Women Physicians’ Health Study. Acad Med. 1999;74(6):695–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Coombs AAT, King RK. Workplace discrimination: experiences of practicing physicians. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(4):467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual The Joanna Briggs Institute. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, et al. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. Am Psychol. 2007;62(4):271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fine E, Sheridan J, Bell CF, Carnes M, Neimeko CJ, Romero M. Teaching Academics about Microaggressions: A Workshop Model Adaptable to Various Audiences. Understanding Interventions Journal. 2007:271. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Castilla EJ. Gender, race, and meritocracy in organizational careers. Am J Sociol. 2008;113(6):1479–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaiser CR, Major B, Jurcevic I, Dover TL, Brady LM, Shapiro JR. Presumed fair: Ironic effects of organizational diversity structures. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2013;104(3):504 10.1037/a0030838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cortina LM, Kabat-Farr D, Leskinen EA, Huerta M, Magley VJ. Selective incivility as modern discrimination in organizations: Evidence and impact. J Manage. 2013;39(6):1579–1605. 10.1177/0149206311418835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miner KN, Settles IH, Pratt-Hyatt JS, Brady CC. Experiencing incivility in organizations: The buffering effects of emotional and organizational support. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2012;42(2):340–372. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00891.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O’Brien KR, McAbee ST, Hebl MR, Rodgers JR. The impact of interpersonal discrimination and stress on health and performance for early career STEM academicians. Front Psychol. 2016;7:615 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gee GC, Spencer MS, Chen J, Takeuchi D. A nationwide study of discrimination and chronic health conditions among Asian Americans. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1275–1282. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.091827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brondolo E, Hausmann LR, Jhalani J, et al. Dimensions of perceived racism and self-reported health: examination of racial/ethnic differences and potential mediators. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42(1):14–28. 10.1007/s12160-011-9265-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Flexner A Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. The Medical Education of the Negro, Chapter XIV, page 180: The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching;1910. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Affair. 2002;21(5):90–102. 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(9):997–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.LaVeist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002:296–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Montenegro RE. My name is not “Interpreter”. JAMA. 2016;315(19):2071–2072. 10.1001/jama.2016.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Slaves Gupta R.. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(9):671–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Williams M. Sick and tired. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(3):568–570. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Poole KG Jr. Patient-experience data and bias - What ratings don’t tell us. New Engl J Med. 2019;380(9):801–803. 10.1056/NEJMp1813418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.WebMD News Staff. Patient prejudice survey results. WebMD. 2017. https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/news/20171018/patient-prejudice-survey-results?ecd=stat. Accessed March 2, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sotto-Santiago S, Slaven JE, Rohr-Kirchgraber T. (Dis)Incentivizing patient satisfaction metrics: the unintended consequences of institutional bias. Health Equity. 2019;3(1):13–18. 10.1089/heq.2018.0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Association AM. AMA code of medical ethics. American Medical Association; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Civil Rights Act of 1964. Pub. L. 88–352, 78 Stat 241 In:1964. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kaplan SE, Raj A, Carr PL, Terrin N, Breeze JL, Freund KM. Race/ethnicity and success in academic medicine: Findings from a longitudinal multi-institutional study. Acad Med. 2018;93(4):616–622. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sheridan J, Savoy JN, Kaatz A, Lee Y-G, Filut A, Carnes M. Write More Articles, Get More Grants: The Impact of Department Climate on Faculty Research Productivity. J Womens Health. 2017. 10.1089/jwh.2016.6022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Carnes M, Devine PG, Manwell LB, et al. The effect of an intervention to break the gender bias habit for faculty at one institution: A cluster randomized, controlled trial. Acad Med. 2015;90(2):221–230. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Devine PG, Forscher PS, Cox WTL, Kaatz A, Sheridan J, Carnes M. A gender bias habit-breaking intervention led to increased hiring of female faculty in STEMM departments. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2017;73:211–215. 10.1016/j.jesp.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Carnes M, Devine PG, Isaac C, et al. Promoting institutional change through bias literacy. J Divers High Educ. 2012;5(2):63–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]