Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a versatile bacterium found in various environments. It can cause severe infections in immunocompromised patients and naturally resists many antibiotics. The World Health Organization listed it among the top priority pathogens for research and development of new antimicrobial compounds. Quorum sensing (QS) is a cell-cell communication mechanism, which is important for P. aeruginosa adaptation and pathogenesis. Here, we validate the central role of the PqsE protein in QS particularly by its impact on the regulator RhlR. This study challenges the traditional dogmas of QS regulation in P. aeruginosa and ties loose ends in our understanding of the traditional QS circuit by confirming RhlR to be the main QS regulator in P. aeruginosa. PqsE could represent an ideal target for the development of new control methods against the virulence of P. aeruginosa. This is especially important when considering that LasR-defective mutants frequently arise, e.g., in chronic infections.

KEYWORDS: cell-cell communication, gene regulation, pyocyanin, virulence factors

ABSTRACT

The bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa has emerged as a central threat in health care settings and can cause a large variety of infections. It expresses an arsenal of virulence factors and a diversity of survival functions, many of which are finely and tightly regulated by an intricate circuitry of three quorum sensing (QS) systems. The las system is considered at the top of the QS hierarchy and activates the rhl and pqs systems. It is composed of the LasR transcriptional regulator and the LasI autoinducer synthase, which produces 3-oxo-C12-homoserine lactone (3-oxo-C12-HSL), the ligand of LasR. RhlR is the transcriptional regulator for the rhl system and is associated with RhlI, which produces its cognate autoinducer C4-HSL. The third QS system is composed of the pqsABCDE operon and the MvfR (PqsR) regulator. PqsABCD synthetize 4-hydroxy-2-alkylquinolines (HAQs), which include ligands activating MvfR. PqsE is not required for HAQ production and instead is associated with the expression of genes controlled by the rhl system. While RhlR is often considered the main regulator of rhlI, we confirmed that LasR is in fact the principal regulator of C4-HSL production and that RhlR regulates rhlI and production of C4-HSL essentially only in the absence of LasR by using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry quantifications and gene expression reporters. Investigating the expression of RhlR targets also clarified that activation of RhlR-dependent QS relies on PqsE, especially when LasR is not functional. This work positions RhlR as the key QS regulator and points to PqsE as an essential effector for full activation of this regulation.

IMPORTANCE Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a versatile bacterium found in various environments. It can cause severe infections in immunocompromised patients and naturally resists many antibiotics. The World Health Organization listed it among the top priority pathogens for research and development of new antimicrobial compounds. Quorum sensing (QS) is a cell-cell communication mechanism, which is important for P. aeruginosa adaptation and pathogenesis. Here, we validate the central role of the PqsE protein in QS particularly by its impact on the regulator RhlR. This study challenges the traditional dogmas of QS regulation in P. aeruginosa and ties loose ends in our understanding of the traditional QS circuit by confirming RhlR to be the main QS regulator in P. aeruginosa. PqsE could represent an ideal target for the development of new control methods against the virulence of P. aeruginosa. This is especially important when considering that LasR-defective mutants frequently arise, e.g., in chronic infections.

INTRODUCTION

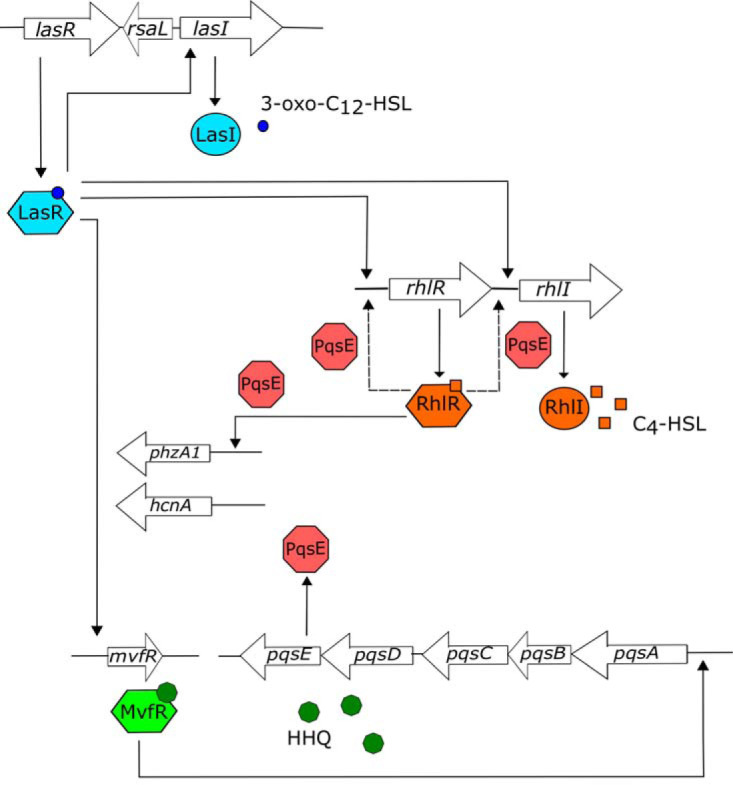

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a bacterium found in a large variety of environments, is most closely associated with human activities (1). This opportunistic human pathogen can cause infections in diverse animals and plants. Its ability to adapt to various conditions has been linked to the many layers of regulation allowing it to control the expression of virulence factors and optimize survival. Quorum sensing (QS) is a mechanism that relies on the release of small signaling molecules as a way to regulate the expression of several genes in a population density-dependent manner. In P. aeruginosa, three QS systems are hierarchically organized (Fig. 1). The las system, which is composed of the transcriptional regulator LasR and the acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) synthase LasI, is generally considered to be at the top of the regulatory hierarchy. LasR is activated by 3-oxo-C12-homoserine lactone (3-oxo-C12-HSL), the autoinducing signal produced by LasI. This system regulates several virulence functions such as elastase (LasB) and phospholipase C (PlcB) but also the gene encoding the LasI synthase (2–6). LasR also activates the transcription of the rhlI and rhlR genes, which code for the AHL synthase RhlI and the transcriptional regulator RhlR (5, 7). In this second AHL-mediated QS system of P. aeruginosa, RhlR associates with C4-HSL, produced by RhlI, and activates the transcription of genes implicated in several functions, such as the biosynthesis of rhamnolipids (rhlAB), hydrogen cyanide (hcnABC), and phenazines (two orthologous phzABCDEFG operons) as well as genes encoding lectins (lecA and lecB) (2, 5, 8–13). The third QS system relies on signaling molecules of the 4-hydroxy-2-alkylquinoline (HAQ) family. The transcriptional regulator MvfR (PqsR) responds to dual ligands 4-hydroxy-2-heptylquinoline (HHQ) and with higher affinity to the Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS; 3,4-dihydroxy-2-alkylquinoline) to activate the transcription of the pqsABCDE operon, which is responsible for their synthesis (14). While LasR activates the transcription of the mvfR gene and the pqs operon, RhlR has a negative effect on the transcription of pqsABCDE (15–17).

FIG 1.

Schematic representation of quorum sensing regulation by RhlR and PqsE in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The dotted lines represent interactions mostly visible in a LasR-deficient background.

LasR-defective mutants frequently arise in various environments (18–22). It could be expected that these mutants would be unable to regulate QS-dependent genes; however, we have shown that RhlR is also able to activate the transcription of LasR target genes when the latter is nonfunctional (23). Indeed, LasR-defective strains expressing RhlR-regulated functions are found (22, 24, 25), implying that QS is not abolished in the absence of LasR. In recent work, a lasR mutant isolated from the lungs of an individual with cystic fibrosis expressed a rhl system that acted independently of the las system (26). It allowed this strain to produce factors essential for its growth under a specific condition that would normally require a functional LasR. When evolved under controlled conditions, this strain gained a mutation in MvfR (PqsR) making it unable to produce PQS and to activate the RhlR-dependent genes, highlighting the link between the pqs operon and RhlR.

Although a thioesterase activity of PqsE could participate in the biosynthesis of HAQs (27), the protein encoded by the last gene of the pqs operon is not required, since a pqsE mutant shows no defect in HAQ production (14). On the other hand, PqsE is implicated in the regulation of genes that include many of the RhlR-dependent targets, such as the phz and hcn operons and the lecA gene, through an unknown mechanism (28–33). An impact of PqsE on the RhlR-dependent regulon was proposed; for instance, PqsE could enhance the affinity of RhlR for C4-HSL (28) or even synthesize an alternative ligand for RhlR (34). Importantly, such function is independent of its thioesterase function, as inhibitors of this activity had no impact on the regulatory functions of PqsE (27, 28).

In this study, we validate that activation of RhlR-dependent QS strongly relies on the presence of a functional PqsE and reveal that this is especially important for activation of the rhl system in cases where LasR is not functional. This makes RhlR the key QS regulator and points to PqsE as an essential effector for full activation of this regulation. These findings thus strengthen the position of RhlR as the master regulator of QS and place PqsE at the center of QS regulatory circuitry in P. aeruginosa.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

RhlR is not the main activator of C4-HSL production.

Quorum sensing regulation is typically described as a partnership between a LuxI-type AHL synthase and a LuxR-type transcriptional regulator. The LuxR-type regulator is activated by a cognate AHL and then regulates the transcription of target genes as well as the gene encoding the synthase, which upregulates AHL production, resulting in an autoinducing loop. In P. aeruginosa, the 3-oxo-C12-HSL synthase LasI is associated with the LasR regulator and the C4-HSL synthase RhlI with the RhlR regulator. Interestingly, LasR regulates the transcription of both rhlI and rhlR genes (2, 5, 7, 35); actually, it has been argued that LasR, and not RhlR, is the primary regulator of rhlI (35). Accordingly, we previously reported that C4-HSL production is decreased in a lasR mutant (23, 26). Indeed, a study in strain 148 showed that LasR binds the lux box found in the promoter region of rhlI but that RhlR does not (36), while other studies showing a direct regulation of rhlI by RhlR were actually performed in a heterologous host, in the absence of LasR (7, 35). Together, these reports would suggest that RhlR mostly activates the transcription of rhlI when LasR is unable to.

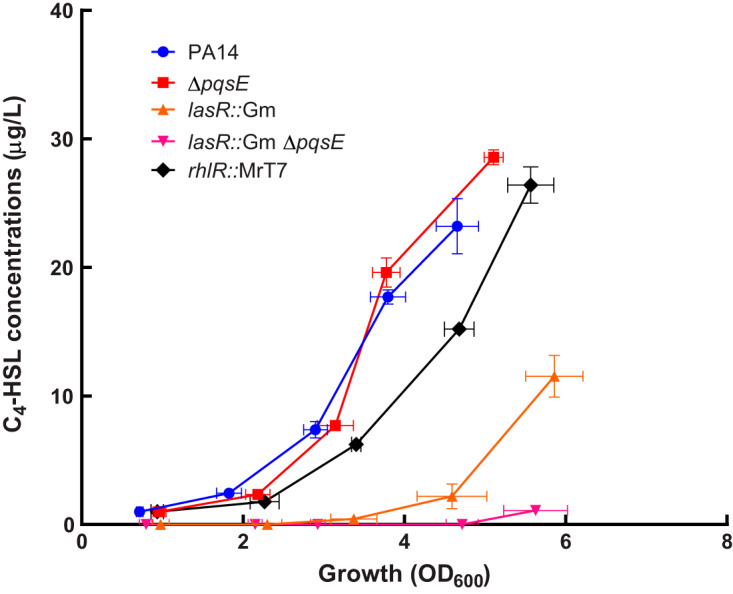

To verify that RhlR is not the main regulator of C4-HSL production in a LasR-positive background, we measured concentrations of this AHL in cultures using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The production of C4-HSL is only detectable at the stationary phase in a lasR mutant, while in a rhlR mutant, the production is only slightly delayed compared to that of wild-type (WT) P. aeruginosa strain PA14 (Fig. 2). This concurs with the often-overlooked idea (e.g. see reference 37) that it is LasR, rather than RhlR, that is primarily responsible for activating the transcription of rhlI and thus the production of C4-HSL, the ligand of RhlR. Interestingly, production is even more diminished in a double lasR pqsE mutant, while it is not affected at all in the ΔpqsE mutant, indicating PqsE has a role in LasR-independent activation of C4-HSL production (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

C4-HSL production depends mostly on LasR. C4-HSL production was measured in cultures of PA14 and ΔpqsE, lasR::Gm, lasR::Gm ΔpqsE, and rhlR::MrT7 mutants at different time points during growth. The values are means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three replicates.

PqsE is important for LasR-independent quorum sensing.

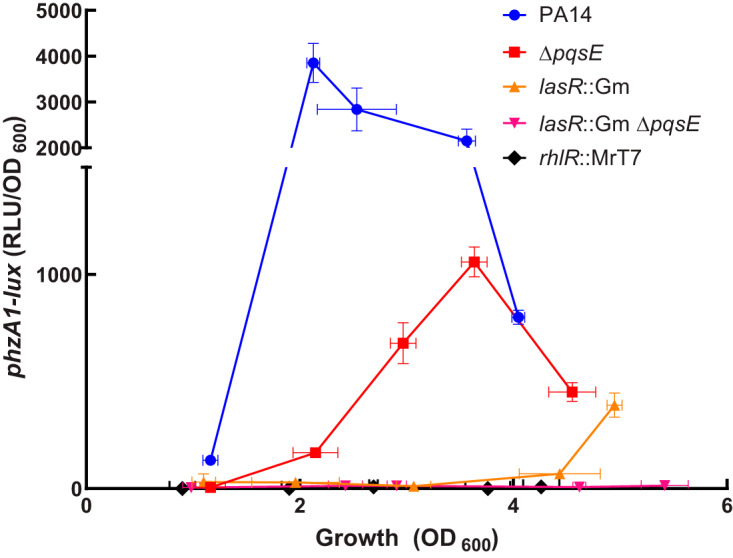

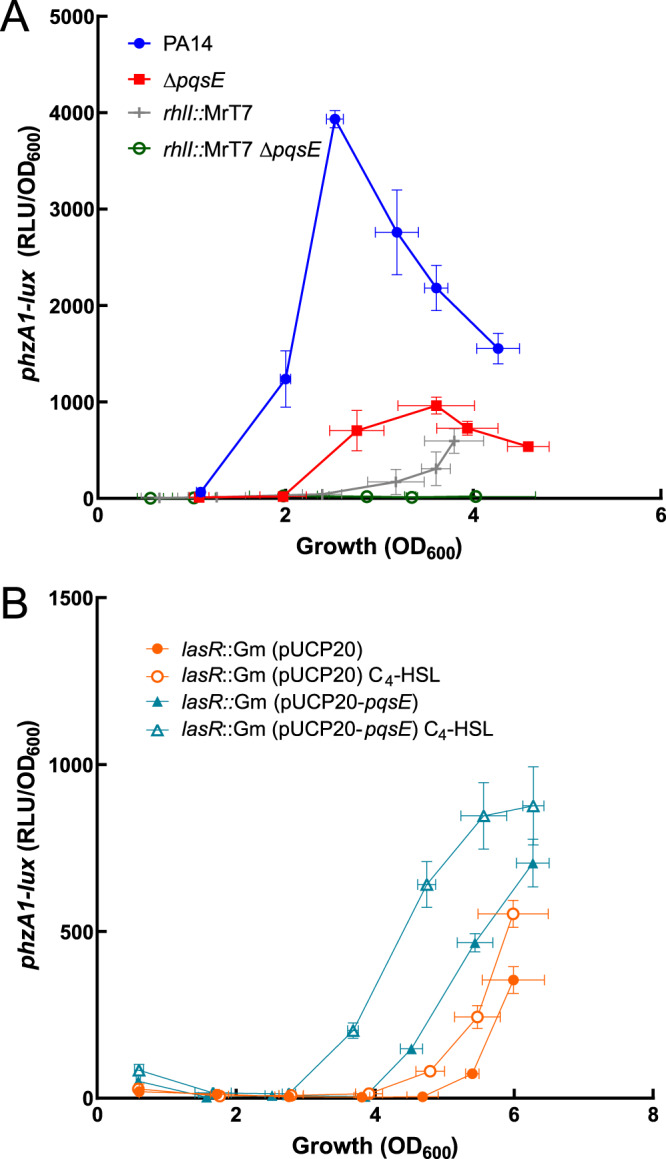

A plausible explanation for the results presented in Fig. 2 is that RhlR is a secondary regulator of rhlI, mostly important in the absence of LasR only, and that the absence of PqsE negatively affects the activity of RhlR only when LasR is not functional. To verify this hypothesis, we needed to investigate the activity of RhlR through one of its primary targets. Phenazines are redox-active metabolites produced by P. aeruginosa and are synthetized via two redundant operons: phzA1-G1 (phz1) and phzA2-G2 (phz2). These operons are almost identical and encode proteins that catalyze the synthesis of phenazine-1-carboxylic acid (PCA). PCA converts into derivatives such as pyocyanin, the blue pigment characteristic of P. aeruginosa cultures (38). The phz operons are differentially regulated depending on conditions, but the phz1 operon shows higher expression than phz2 in planktonic cultures of strain PA14 (39). The promoter of the phz1 operon contains a las box which can be recognized by both LasR and RhlR (40). We measured the activity of a chromosomal phzA1-lux reporter in both lasR and rhlR mutants to verify their involvement in the regulation of the transcription of the phz1 operon (Fig. 3). The transcription of phz1 is completely abolished in a rhlR mutant but it is still observed in a lasR mutant, although it starts much later than for the WT (after an optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 4.0). This is consistent with the delayed production of pyocyanin (23, 41) and C4-HSL (Fig. 2) observed in cultures of a lasR mutant. Since we know that transcription of phz1 and production of pyocyanin are abrogated in a double lasR rhlR mutant (23, 41), these results indicate that RhlR, but not LasR, regulates the transcription of phzA1 and that RhlR is responsible for the late activation of phzA1 expression in a lasR-negative background. We used transcription of the phz1 operon to further study the influence of PqsE on RhlR-dependent regulation. Even if cultures of a pqsE mutant do not show any visible pyocyanin, we still observe clear expression of phz1 (Fig. 3). Since there is no pyocyanin produced in the WT until an OD600 of around 2.5 even if there is expression from the phzA1 promoter, there seems to be a minimal level of expression of phz genes for detectable pyocyanin. Also, pyocyanin is not a direct product of the phz operons and it is possible that other enzymes (e.g., PhzM or PhzS) implicated in the conversion of PCA to pyocyanin do not follow the same pattern of expression in this background (29). The transcription of phzA1 is completely abolished in a double lasR pqsE mutant. Many studies report an impact of PQS-dependent QS on the regulation of the phz operons or pyocyanin production (28, 31, 39, 41, 42). More specifically, this effect necessitates a functional PqsE (28, 42).

FIG 3.

Transcription of the phz1 operon absolutely requires RhlR and PqsE in a lasR-negative background. Luminescence of a phzA1-lux chromosomal reporter was measured in P. aeruginosa PA14 and various isogenic mutants at different time points during growth. The values are means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three replicates.

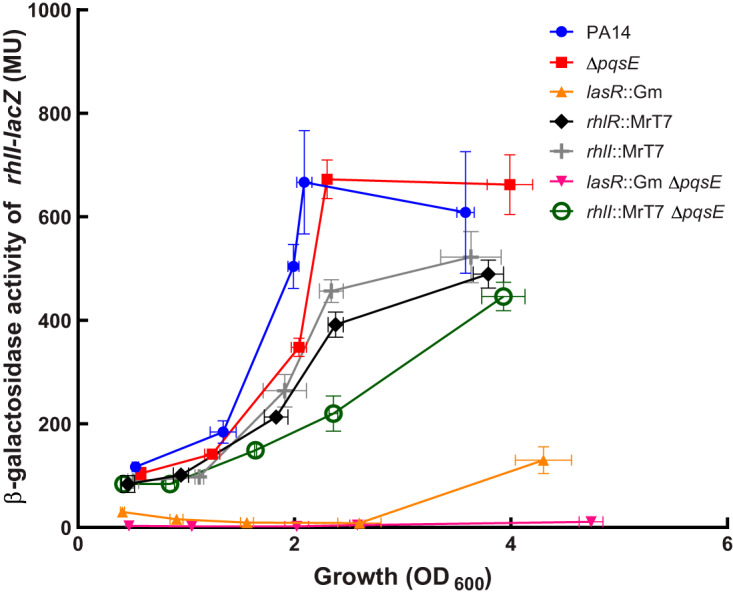

Because LasR regulates the expression of rhlI (5, 7, 23), we performed a β-galactosidase assay using a rhlI-lacZ reporter to verify the impact of PqsE on the transcription of rhlI. As expected, transcription of rhlI is much delayed in a lasR mutant (Fig. 4). This is compatible with the late activation of phz1 we observed (Fig. 3) and is apparently occurring because RhlR takes the relay in activating the transcription of rhlI following the initial activation by LasR. When the pqsE gene is inactivated in a lasR background, very low transcription of rhlI is observed (Fig. 4) which concurs with the production of C4-HSL in this background (Fig. 2) and which agrees with a PqsE-dependent activity of RhlR. Again, since RhlR takes over regulating the production of C4-HSL following the initial activation by LasR, the transcription of rhlI slows down in rhlR and rhlI mutants after an OD600 of 2.0, when LasR main activity is decreasing (the levels of 3-oxo-C12-HSL are rapidly declining) (23, 31). Together, these data point to a role for PqsE in LasR-independent regulation of the rhl system.

FIG 4.

The transcription of rhlI requires PqsE in a lasR mutant. The β-galactosidase activity of a rhlI-lacZ reporter was measured in various backgrounds at different time points during growth. The values are means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three replicates.

PqsE/RhlR/C4-HSL collude to activate LasR-independent quorum sensing.

Since C4-HSL has an effect on RhlR activity (2, 7, 28), we needed to better understand the functional complementary of C4-HSL with PqsE in modulating the activity of RhlR. We measured the activity of the phzA1-lux reporter in a rhlI mutant as well as in a double rhlI pqsE mutant. Transcription of phzA1 in the rhlI mutant was delayed, but not abolished, suggesting that RhlR utilizes its AHL ligand to activate the phz1 operon but that its presence is not essential (Fig. 5A). However, when both C4-HSL and PqsE are absent (rhlI pqsE double-negative background), there is no residual transcription of phz1 (Fig. 5A), like in the rhlR-negative background (Fig. 3). The profile of expression of phz1 significantly differs between pqsE and rhlI mutants (P values of <0.05 from OD600s of 3.0 to 3.6). In the pqsE mutant, the expression starts at an OD600 of around 2.0, while in the rhlI mutant, it starts later (OD600 of around 3.5) and keeps augmenting through the rest of the growth curve. This suggests that both elements increase the activity of RhlR through different mechanisms.

FIG 5.

The impacts of C4-HSL and PqsE on RhlR activity. The expression of phzA1-lux is cumulative. (A) Luminescence of a phzA1-lux chromosomal reporter was measured in WT and isogenic ΔpqsE and rhlI::MrT7 mutants and double mutant rhlI::MrT7 ΔpqsE at different time points during growth. (B) Luminescence of the phzA1-lux chromosomal reporter was measured in a lasR::Gm background with either empty vector pUCP20 or pUCP20-pqsE with or without the addition of C4-HSL. The values are means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three replicates.

Since the absence of LasR seems to impose the requirement for PqsE to achieve efficient RhlR activity, we overexpressed pqsE in a lasR-null background. As previously shown (43), the constitutive expression of PqsE augments and advances the transcription of phzA1 (Fig. 5B). When we added exogenous C4-HSL in the lasR mutant bearing a plasmid-borne pqsE, the transcription of phz1 started even earlier and reached higher levels than with either one separately (P values of 0.046 and 0.002, respectively). Farrow et al. (28) proposed that PqsE acts by enhancing the affinity of RhlR for C4-HSL. However, we see that PqsE increases the activity of RhlR even in the absence of RhlI (Fig. 4 and 5A), thus not supporting this hypothesis; our data suggest that RhlR full activity depends on both C4-HSL and PqsE and that their impact is cumulative.

The induction of RhlR activity by PqsE in the absence of rhlI could be explained by the proposed PqsE-dependent production of a putative alternative RhlR ligand. Indeed, Mujurkhee and colleagues (13) observed activation of rhlA transcription by adding culture-free fluids from a ΔrhlI mutant to a QS mutant expressing rhlR under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter. They proposed in a subsequent study that this activity was PqsE dependent (34). We thus tested the effect of pqsE, rhlI, and rhlI pqsE mutants cell-free culture fluids on the activation of phzA1-lux in the rhlI pqsE double-negative background. As expected, the activity of the reporter is strongly induced by culture supernatants from PA14 or a pqsE mutant (which both contain C4-HSL). On the other hand, there is no activation by supernatants from rhlI and rhlI pqsE mutants (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), even when combined with an overexpression of rhlR (data not shown). This argues against an unknown RhlR inducer whose production would require PqsE. The same results were obtained when using an hcnA-lacZ reporter (data not shown).

A putative ligand produced by PqsE is not responsible for the PqsE-dependent regulation of the transcription of phzA1-lux. Cell-free supernatant(s) (final 30%) recovered from 18-h cultures was added to cultures of a rhlI::MrT7 ΔpqsE double mutant bearing a phzA1-lux reporter, and activity was measured after a 4-h incubation. The values are means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three replicates. Association with different letters represents statistical significance based on ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparison tests. Download FIG S1, PDF file, 0.1 MB (68.5KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Groleau et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

To validate our model, we looked at the regulation of the hcnABC operon, a dual target of both LasR and RhlR (12, 41), and obtained results similar to what we observed for the phz1 operon and the rhlI gene (see Fig. S2). Taken altogether, our data highlight a possible homeostatic loop between RhlR-RhlI-PqsE and demonstrate that PqsE is essential for maintaining control of RhlR-dependent QS functions in a LasR-independent way.

Transcription of hcnABC requires PqsE in a lasR-negative background. (A) The β-galactosidase activity of an hcnA-lacZ reporter was measured in various backgrounds at different time points during growth. (B) A subset of data shown in panel A showing the activity in the lasR and lasR pqsE mutant backgrounds only. The values are means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three replicates. Download FIG S2, PDF file, 0.2 MB (166.8KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Groleau et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

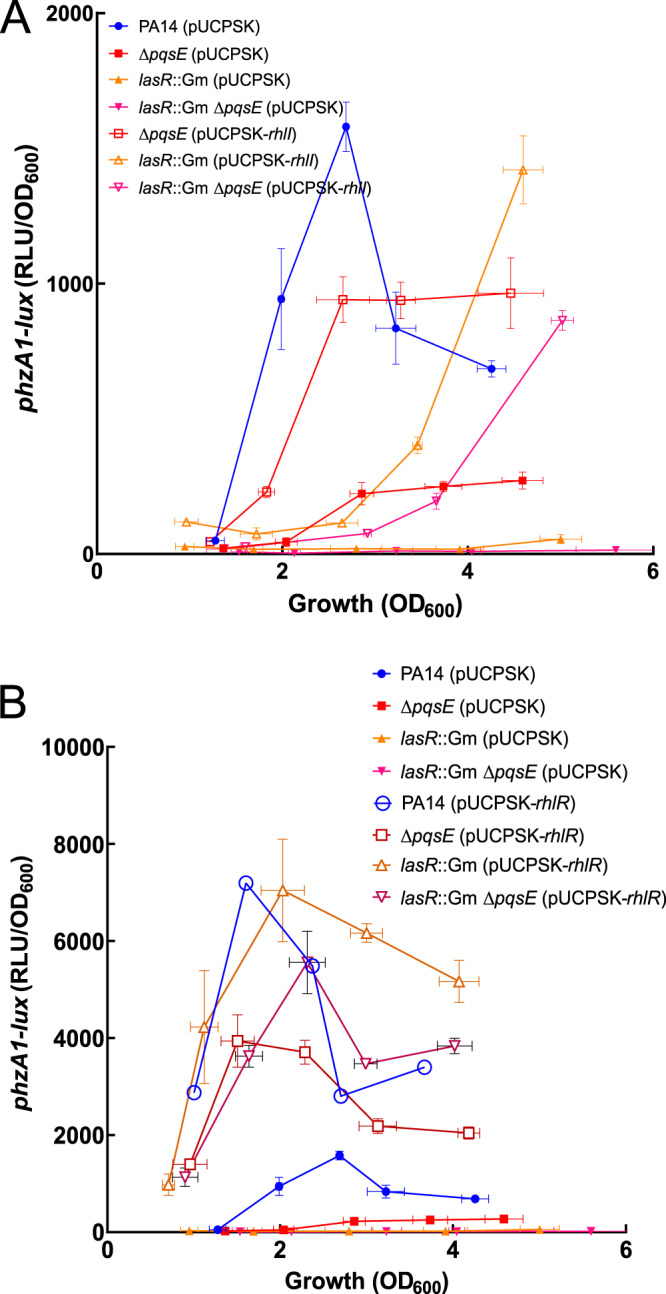

Excess RhlR, but not C4-HSL, can overcome a PqsE deficiency.

We then sought to better understand how C4-HSL and PqsE both contribute to RhlR activity. First, we verified if overproduction of C4-HSL could counterbalance a lack of PqsE. It was already shown that adding C4-HSL alone could not restore pyocyanin production in a triple ΔlasR ΔrhlI ΔpqsA mutant, but that adding PQS and C4-HSL together could (41). We thus used a plasmid-borne plac-rhlI for constitutive C4-HSL production and measured its effects on the transcription of phz1 and on pyocyanin production in various backgrounds. Overexpression of rhlI complements the transcription of phz1 in a lasR mutant enough to show pyocyanin production at the stationary phase (Fig. 6A; see also Fig. S3). As expected, this complementation was not as efficient when a pqsE mutation was added to the lasR-negative background, as there was even less transcription of phz1 (P values of <0.05 at all growth phases) (Fig. 6A). Taken together, these results confirm that C4-HSL cannot counterbalance the absence of PqsE and highlight an important role for PqsE in regulating RhlR-dependent genes; this is especially striking in the absence of LasR.

FIG 6.

Effects of rhlI and rhlR overexpression on phz1 transcription. Luminescence of a phzA1-lux chromosomal reporter was measured in PA14, ΔpqsE, lasR::Gm, and lasR::Gm ΔpqsE mutants at different time points during growth with overexpression of RhlI (A) or RhlR (B). The values are means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three replicates.

Effects of rhlI and rhlR overexpression on pyocyanin (PYO) production. The absorbance of supernatants from cultures at an OD600 of 4.5 was measured at 695 nm. The values are means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three replicates. ****, P < 0.0001; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; ns, not significant based on t tests. Download FIG S3, PDF file, 0.1 MB (48.3KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Groleau et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

We then looked at the overexpression of RhlR, since it partially restores pyocyanin production in a ΔpqsE background (30). We observed an augmentation in both the transcription of phzA1 and pyocyanin production (Fig. 6B and S3). Figure S3 shows that when RhlR is overexpressed, both lasR and lasR pqsE mutants produce higher levels of pyocyanin, coupled with strong activation of phzA1-lux expression in both backgrounds. This is the first ever report of restoration of phz1 transcription and pyocyanin production in the absence of PqsE. Surprisingly, we observed a discrepancy between the transcription from the phzA1 promoter and pyocyanin production, which indicates that the transcription of the target genes shows a more realistic portrait of the activity of RhlR than only looking at pyocyanin production.

Further supporting our model, the transcription of phzA1 and the production of pyocyanin when rhlR was overexpressed were higher in the lasR mutant than in the lasR pqsE mutant (P value of <0.05 at OD600s of 2.0 to 4.0), and these results again confirm an effect of PqsE on RhlR activity.

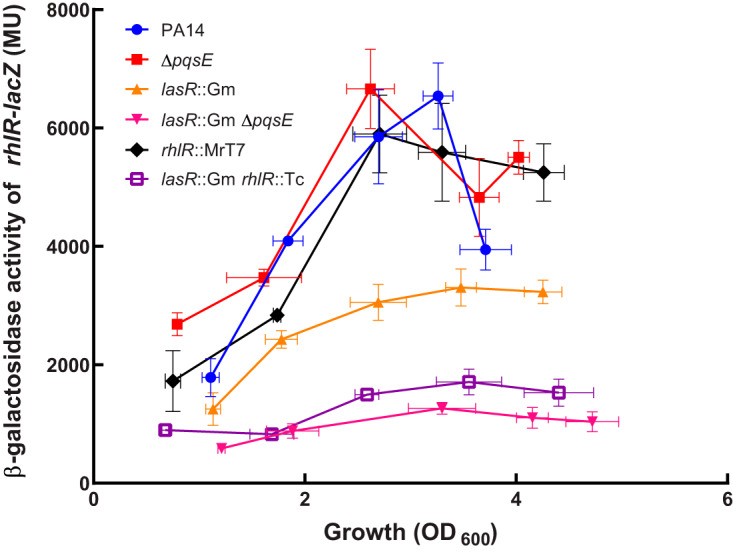

PqsE affects RhlR regulatory activity on its targets, including itself, in the absence of LasR.

The very late activity of phz1 in lasR-negative backgrounds can be explained by low levels of RhlR, whose initial transcription also requires LasR (2, 5–7, 35). When measuring the activity of an rhlR-lacZ reporter, there was indeed a lower transcription of rhlR in a lasR mutant (Fig. 7). Since overexpression of rhlI did not lead to full activation of the phz genes in a double lasR pqsE mutant background (Fig. 6A), we hypothesized that this was instead caused by low transcription of the rhlR gene. Interestingly, the level of rhlR transcription was even lower in the double lasR pqsE mutant background than in the single lasR mutant. This result is unexpected since the transcription of rhlR is weakly affected in a pqsE-null background (30). Because RhlR can activate the target genes of LasR when the latter is absent (23), we hypothesized that RhlR could therefore regulate itself, explaining the impact of PqsE only in the absence of LasR. Transcription of rhlR-lacZ was accordingly lower in a double lasR rhlR mutant, to levels similar to those in the lasR pqsE mutant (nonsignificant, P > 0.05 at all growth phases) (Fig. 7). This indicates that RhlR directs its own transcription only in the absence of LasR and that PqsE is important for this activity. These data confirm that PqsE is an essential element in RhlR activity when LasR is not functional.

FIG 7.

PqsE affects RhlR autoregulation. The β-galactosidase activity of a rhlR-lacZ reporter was measured in various backgrounds at different time points during growth. The values are means ± standard deviations (error bars) frrom three replicates.

Conclusion.

The complex quorum sensing circuitry of P. aeruginosa has been extensively studied, and we know all three systems are intimately intertwined (44, 45). Although RhlR is often believed to form a traditional autoinducing pair with rhlI, we confirm here that LasR really is the main activator of C4-HSL production and that RhlR activation of rhlI is mainly observed in the absence of a functional LasR. LasR is also an activator of the pqs operon and thus of PqsE. However, production of C4-HSL and PQS are not completely abolished in a lasR mutant, only delayed. In a lasR-null background, the importance of RhlR and PqsE on the activation of phzA1, rhlI, or hcnA is higher than in the WT, since LasR is at the top of the regulation cascade. This allowed us to observe that RhlR is able to fully activate target genes only if PqsE is present. The function of PqsE has been a subject of many studies but is still enigmatic (32). In this work, we show that PqsE most likely promotes the function of RhlR and that this effect seems independent of the presence of C4-HSL or another putative ligand, as previously proposed.

Under laboratory conditions, P. aeruginosa can afford a late activation of QS or even no activation of QS at all. In a more competitive environment, it is likely there is pressure to control these genes and to activate their transcription independently of LasR when necessary. PqsE could thus be important as a trigger for stronger and/or earlier RhlR activity. A growing number of studies report on the presence of LasR-deficient variants in chronic infections settings (18, 19, 22). With the absence of a functional LasR in these strains, the traditional QS hierarchy is altered and independent expression of RhlR becomes necessary for the bacteria to activate functions important for survival in hosts, such as virulence factors (like exoproteases and HCN) or biofilm formation (rhamnolipids and lectins).

Importantly, among LasR-deficient P. aeruginosa strains isolated from clinical settings, some still express a functional quorum sensing response through the activity of RhlR, independently of LasR (22, 26). Since this study was limited to the prototypical strain PA14, it will be important to extend our findings and investigate the implication of PqsE in the activation of the RhlR regulon in diverse clinical and environmental isolates in order to better understand its role in QS gene regulation in P. aeruginosa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains are listed in Table 1. Plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. Unless otherwise stated, bacteria were routinely grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB; BD Difco, Canada) at 37°C in a TC-7 roller drum (NB, Canada) at 240 rpm or on lysogeny broth (LB) agar plates. When antibiotics were needed, the following concentrations were used: for Escherichia coli, 15 μg/ml tetracycline and 100 μg/ml carbenicillin, for P. aeruginosa, 100 μg/ml gentamicin, tetracycline at 125 μg/ml (solid) or 75 μg/ml (liquid), and 250 μg/ml carbenicillin. Diaminopimelic acid (DAP) was added to cultures of the auxotroph E. coli χ7213 at 62.5 μg/ml. All plasmids were transformed in bacteria by electroporation (46).

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F−, ϕ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) phoA supE44 λ− thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Lab collection |

| χ7213 | thr-1 leuB6 fhuA21 lacY1 glnV44 recA1 ΔasdA4 Δ(zhf-2::Tn10) thi-1 RP4-2-Tc::Mu [λ pir] | Lab collection |

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| ED14/PA14 | Clinical isolate UCBPP-PA14 | 50 |

| ED36 | ΔpqsE | 14 |

| ED69 | lasR::Gm | 14 |

| ED247 | lasR::Gm ΔpqsE | This study |

| ED503 | rhlR::Gm | 30 |

| ED297 | rhlI::MrT7 | 51 |

| ED3579 | rhlI::MrT7 ΔpqsE | This study |

| ED266 | lasR::Gm rhlR::Tc | 23 |

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| pCDS101 | Promoter of phz1 in mini-CTX-lux, Tetr | 52 |

| pPCS1002 | rhlR-lacZ reporter, Carbr | 2 |

| pSB219.9A | pRIC380 carrying lasR::Gm | 47 |

| pME3846 | rhlI-lacZ translational reporter, Tetr | 53 |

| pME3826 | hcnA-lacZ translational reporter, Tetr | 54 |

| pUCPSK | Pseudomonas and Escherichia shuttle vector, Carbr | 55 |

| pMIC62 | rhlR gene under control of the lac promoter in pUCPSK | John Mattick |

| pUCPrhlI | rhlI gene under control of the lac promoter in pUCPSK | 47 |

| pUCP20 | Pseudomonas and Escherichia shuttle vector, Carbr | 56 |

| pUCP20-pqsE | pqsE gene under control of the lac promoter in pUCP20, Carbr | 57 |

All experiments presented in this work were performed with three biological replicates and repeated at least twice.

Construction of the double ΔpqsE mutants.

A knockout in both rhlI and pqsE was constructed by transfer between chromosomes (46). The genomic DNA (gDNA) of strain ED297 rhlI::MrT7 was extracted using the EasyPure bacteria genomic kit (Trans Gen Biotech, China). Three milliliters of an overnight culture of ΔpqsE was centrifuged (16,000 × g, 2 min) in separate microtubes. Pellets were washed twice with 300 mM sucrose. The pellets were combined in a final volume of 100 μl 300 mM sucrose. Five hundred nanograms of gDNA was added to the bacterial suspension, and the mixture was transferred to a 0.2-mm electroporation cuvette. The cells were electroporated at 2,500 V, immediately transferred to 1 ml LB, and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Selection was performed on LB agar containing gentamicin. Clones were selected and verified by PCR. The lasR::Gm mutation was introduced in the ΔpqsE background by allelic exchange using pSB219.9A as described (14, 47).

Construction of phz1-lux chromosomal reporter strains.

The mini-CTX-phz1-lux construct was integrated into the chromosomes of PA14 WT and mutants by conjugation on LB agar plates containing DAP with E. coli χ7213 containing the pCDS101 plasmid. Selection was performed on LB agar plates containing tetracycline.

β-Galactosidase activity assays and luminescence reporter measurements.

Strains containing the reporter fusions were grown overnight in TSB with appropriate antibiotics and diluted at an OD600 of 0.05 in TSB. For lacZ reporter assays, culture samples were regularly taken for determination of growth (OD600) and β-galactosidase activity (48). For lux reporter assays, luminescence was measured using a Cytation 3 multimode microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, USA). When mentioned, C4-HSL was added at a final concentration of 20 μM from a stock solution prepared in high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade acetonitrile. Acetonitrile only was added in controls. All OD600 measurements were performed with a NanoDrop ND100 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Canada).

Pyocyanin quantification.

Overnight cultures of PA14 and mutants were diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 in TSB and grown until an OD600 of 4 to 5 was reached. Cells were removed by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 5 min, and the cleared supernatant was transferred to 96-well microplates. The absorbance at 695 nm was measured using a Cytation 3 multimode microplate reader. Pyocyanin production was determined by dividing the OD695 by the OD600.

Quantification of AHLs.

Analyses were performed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) as described before with 5,6,7,8-tetradeutero-4-hydroxy-2-heptylquinoline (HHQ-d4) as an internal standard. (49).

Data analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using R software version 3.6.3 (http://www.R-project.org) using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post hoc tests at different stages of growth. All conclusions discussed in this paper were based on significant differences. Probability (P) values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sylvain Milot and Marianne Piochon for their help with the LC-MS analyses, Philippe Constant for his help with statistical analyses, and Alison Besse and Fabrice Jean-Pierre for critical reading of the manuscript.

This study was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) operating grants MOP-97888 and MOP-142466 to E.D.

E.D. holds the Canada Research Chair in Sociomicrobiology. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

This work is dedicated to the memory of Benjamin Folch (1980 to 2020).

Footnotes

The review history of this article can be read here.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Anne Shank, University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Peter Jorth, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crone S, Vives-Florez M, Kvich L, Saunders AM, Malone M, Nicolaisen MH, Martinez-Garcia E, Rojas-Acosta C, Catalina Gomez-Puerto M, Calum H, Whiteley M, Kolter R, Bjarnsholt T. 2019. The environmental occurrence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. APMIS 128:220–231. doi: 10.1111/apm.13010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pesci EC, Pearson JP, Seed PC, Iglewski BH. 1997. Regulation of las and rhl quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 179:3127–3132. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3127-3132.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner VE, Bushnell D, Passador L, Brooks AI, Iglewski BH. 2003. Microarray analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing regulons: effects of growth phase and environment. J Bacteriol 185:2080–2095. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2080-2095.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuster M, Lostroh CP, Ogi T, Greenberg EP. 2003. Identification, timing, and signal specificity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-controlled genes: a transcriptome analysis. J Bacteriol 185:2066–2079. doi: 10.1128/jb.185.7.2066-2079.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whiteley M, Lee KM, Greenberg EP. 1999. Identification of genes controlled by quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:13904–13909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert KB, Kim TH, Gupta R, Greenberg EP, Schuster M. 2009. Global position analysis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing transcription factor LasR. Mol Microbiol 73:1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latifi A, Foglino M, Tanaka K, Williams P, Lazdunski A. 1996. A hierarchical quorum-sensing cascade in Pseudomonas aeruginosa links the transcriptional activators LasR and RhIR (VsmR) to expression of the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS. Mol Microbiol 21:1137–1146. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearson JP, Pesci EC, Iglewski BH. 1997. Roles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa las and rhl quorum-sensing systems in control of elastase and rhamnolipid biosynthesis genes. J Bacteriol 179:5756–5767. doi: 10.1128/JB.179.18.5756-5767.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ochsner UA, Reiser J. 1995. Autoinducer-mediated regulation of rhamnolipid biosurfactant synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:6424–6428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brint JM, Ohman DE. 1995. Synthesis of multiple exoproducts in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is under the control of RhlR-RhlI, another set of regulators in strain PAO1 with homology to the autoinducer-responsive LuxR-LuxI family. J Bacteriol 177:7155–7163. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7155-7163.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winzer K, Falconer C, Garber NC, Diggle SP, Camara M, Williams P. 2000. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa lectins PA-IL and PA-IIL are controlled by quorum sensing and by RpoS. J Bacteriol 182:6401–6411. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.22.6401-6411.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pessi G, Haas D. 2000. Transcriptional control of the hydrogen cyanide biosynthetic genes hcnABC by the anaerobic regulator ANR and the quorum-sensing regulators LasR and RhlR in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 182:6940–6949. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.24.6940-6949.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukherjee S, Moustafa D, Smith CD, Goldberg JB, Bassler BL. 2017. The RhlR quorum-sensing receptor controls Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis and biofilm development independently of its canonical homoserine lactone autoinducer. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006504. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Déziel E, Lépine F, Milot S, He J, Mindrinos MN, Tompkins RG, Rahme LG. 2004. Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa 4-hydroxy-2-alkylquinolines (HAQs) reveals a role for 4-hydroxy-2-heptylquinoline in cell-to-cell communication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:1339–1344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307694100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wade DS, Calfee MW, Rocha ER, Ling EA, Engstrom E, Coleman JP, Pesci EC. 2005. Regulation of Pseudomonas quinolone signal synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 187:4372–4380. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.13.4372-4380.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brouwer S, Pustelny C, Ritter C, Klinkert B, Narberhaus F, Häussler S. 2014. The PqsR and RhlR transcriptional regulators determine the level of Pseudomonas quinolone signal synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by producing two different pqsABCDE mRNA isoforms. J Bacteriol 196:4163–4171. doi: 10.1128/JB.02000-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao G, He J, Rahme LG. 2006. Mutation analysis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa mvfR and pqsABCDE gene promoters demonstrates complex quorum-sensing circuitry. Microbiology 152:1679–1686. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28605-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffman LR, Kulasekara HD, Emerson J, Houston LS, Burns JL, Ramsey BW, Miller SI. 2009. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR mutants are associated with cystic fibrosis lung disease progression. J Cyst Fibros 8:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Argenio DA, Wu M, Hoffman LR, Kulasekara HD, Déziel E, Smith EE, Nguyen H, Ernst RK, Larson Freeman TJ, Spencer DH, Brittnacher M, Hayden HS, Selgrade S, Klausen M, Goodlett DR, Burns JL, Ramsey BW, Miller SI. 2007. Growth phenotypes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR mutants adapted to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Mol Microbiol 64:512–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05678.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cabrol S, Olliver A, Pier GB, Andremont A, Ruimy R. 2003. Transcription of quorum-sensing system genes in clinical and environmental isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 185:7222–7230. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.24.7222-7230.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vincent AT, Freschi L, Jeukens J, Kukavica-Ibrulj I, Emond-Rheault JG, Leduc A, Boyle B, Jean-Pierre F, Groleau MC, Déziel E, Barbeau J, Charette SJ, Lévesque RC. 2017. Genomic characterisation of environmental Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from dental unit waterlines revealed the insertion sequence ISPa11 as a chaotropic element. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 93:fix106. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fix106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feltner JB, Wolter DJ, Pope CE, Groleau MC, Smalley NE, Greenberg EP, Mayer-Hamblett N, Burns J, Déziel E, Hoffman LR, Dandekar AA. 2016. LasR variant cystic fibrosis isolates reveal an adaptable quorum-sensing hierarchy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mBio 7:e01513-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01513-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dekimpe V, Déziel E. 2009. Revisiting the quorum-sensing hierarchy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: the transcriptional regulator RhlR regulates LasR-specific factors. Microbiology 155:712–723. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.022764-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kostylev M, Kim DY, Smalley NE, Salukhe I, Greenberg EP, Dandekar AA. 2019. Evolution of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing hierarchy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116:7027–7032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1819796116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou H, Wang M, Smalley NE, Kostylev M, Schaefer AL, Greenberg EP, Dandekar AA, Xu F. 2019. Modulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing by glutathione. J Bacteriol 201:e00685-18. doi: 10.1128/JB.00685-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen R, Déziel E, Groleau MC, Schaefer AL, Greenberg EP. 2019. Social cheating in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing variant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116:7021–7026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1819801116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drees SL, Fetzner S. 2015. PqsE of Pseudomonas aeruginosa acts as pathway-specific thioesterase in the biosynthesis of alkylquinolone signaling molecules. Chem Biol 22:611–618. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farrow JM III, Sund ZM, Ellison ML, Wade DS, Coleman JP, Pesci EC. 2008. PqsE functions independently of PqsR-Pseudomonas quinolone signal and enhances the rhl quorum-sensing system. J Bacteriol 190:7043–7051. doi: 10.1128/JB.00753-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rampioni G, Falcone M, Heeb S, Frangipani E, Fletcher MP, Dubern JF, Visca P, Leoni L, Camara M, Williams P. 2016. Unravelling the genome-wide contributions of specific 2-alkyl-4-quinolones and PqsE to quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog 12:e1006029. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hazan R, He J, Xiao G, Dekimpe V, Apidianakis Y, Lesic B, Astrakas C, Déziel E, Lépine F, Rahme LG. 2010. Homeostatic interplay between bacterial cell-cell signaling and iron in virulence. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000810. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Déziel E, Gopalan S, Tampakaki AP, Lépine F, Padfield KE, Saucier M, Xiao G, Rahme LG. 2005. The contribution of MvfR to Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis and quorum sensing circuitry regulation: multiple quorum sensing-regulated genes are modulated without affecting lasRI, rhlRI, or the production of N-acyl-l-homoserine lactones. Mol Microbiol 55:998–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia-Reyes S, Soberón-Chávez G, Cocotl-Yanez M. 2019. The third quorum-sensing system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Pseudomonas quinolone signal and the enigmatic PqsE protein. J Med Microbiol 69:25–34. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diggle SP, Winzer K, Chhabra SR, Worrall KE, Camara M, Williams P. 2003. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa quinolone signal molecule overcomes the cell density-dependency of the quorum sensing hierarchy, regulates rhl-dependent genes at the onset of stationary phase and can be produced in the absence of LasR. Mol Microbiol 50:29–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mukherjee S, Moustafa DA, Stergioula V, Smith CD, Goldberg JB, Bassler BL. 2018. The PqsE and RhlR proteins are an autoinducer synthase-receptor pair that control virulence and biofilm development in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E9411–E9418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1814023115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Kievit TR, Kakai Y, Register JK, Pesci EC, Iglewski BH. 2002. Role of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa las and rhl quorum-sensing systems in rhlI regulation. FEMS Microbiol Lett 212:101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morales E, Gonzalez-Valdez A, Servin-Gonzalez L, Soberón-Chávez G. 2017. Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing response in the absence of functional LasR and LasI proteins: the case of strain 148, a virulent dolphin isolate. FEMS Microbiol Lett 364:fnx119. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jimenez PN, Koch G, Thompson JA, Xavier KB, Cool RH, Quax WJ. 2012. The multiple signaling systems regulating virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76:46–65. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05007-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mavrodi DV, Bonsall RF, Delaney SM, Soule MJ, Phillips G, Thomashow LS. 2001. Functional analysis of genes for biosynthesis of pyocyanin and phenazine-1-carboxamide from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol 183:6454–6465. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6454-6465.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Recinos DA, Sekedat MD, Hernandez A, Cohen TS, Sakhtah H, Prince AS, Price-Whelan A, Dietrich LE. 2012. Redundant phenazine operons in Pseudomonas aeruginosa exhibit environment-dependent expression and differential roles in pathogenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:19420–19425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213901109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whiteley M, Greenberg EP. 2001. Promoter specificity elements in Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing-controlled genes. J Bacteriol 183:5529–5534. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.19.5529-5534.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cabeen MT. 2014. Stationary phase-specific virulence factor overproduction by a lasR mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One 9:e88743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Folch B, Déziel E, Doucet N. 2013. Systematic mutational analysis of the putative hydrolase PqsE: toward a deeper molecular understanding of virulence acquisition in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One 8:e73727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Higgins S, Heeb S, Rampioni G, Fletcher MP, Williams P, Camara M. 2018. Differential regulation of the phenazine biosynthetic operons by quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1-N. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 8:252. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schuster M, Sexton DJ, Diggle SP, Greenberg EP. 2013. Acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing: from evolution to application. Annu Rev Microbiol 67:43–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams P, Camara M. 2009. Quorum sensing and environmental adaptation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a tale of regulatory networks and multifunctional signal molecules. Curr Opin Microbiol 12:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi KH, Kumar A, Schweizer HP. 2006. A 10-min method for preparation of highly electrocompetent Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells: application for DNA fragment transfer between chromosomes and plasmid transformation. J Microbiol Methods 64:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beatson SA, Whitchurch CB, Semmler AB, Mattick JS. 2002. Quorum sensing is not required for twitching motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 184:3598–3604. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.13.3598-3604.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics, p 352–355. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lépine F, Milot S, Groleau MC, Déziel E. 2018. Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) for the detection and quantification of N-acyl-l-homoserine lactones (AHLs) and 4-hydroxy-2-alkylquinolines (HAQs). Methods Mol Biol 1673:49–59. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7309-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rahme LG, Stevens EJ, Wolfort SF, Shao J, Tompkins RG, Ausubel FM. 1995. Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science 268:1899–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.7604262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liberati NT, Urbach JM, Miyata S, Lee DG, Drenkard E, Wu G, Villanueva J, Wei T, Ausubel FM. 2006. An ordered, nonredundant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 transposon insertion mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:2833–2838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511100103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sibley CD, Duan K, Fischer C, Parkins MD, Storey DG, Rabin HR, Surette MG. 2008. Discerning the complexity of community interactions using a Drosophila model of polymicrobial infections. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000184. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pessi G, Williams F, Hindle Z, Heurlier K, Holden MT, Camara M, Haas D, Williams P. 2001. The global posttranscriptional regulator RsmA modulates production of virulence determinants and N-acylhomoserine lactones in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 183:6676–6683. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.22.6676-6683.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pessi G, Haas D. 2001. Dual control of hydrogen cyanide biosynthesis by the global activator GacA in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. FEMS Microbiol Lett 200:73–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watson AA, Alm RA, Mattick JS. 1996. Construction of improved vectors for protein production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 172:163–164. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.West SE, Schweizer HP, Dall C, Sample AK, Runyen-Janecky LJ. 1994. Construction of improved Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19 and sequence of the region required for their replication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 148:81–86. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu S, Jensen V, Seeliger J, Feldmann I, Weber S, Schleicher E, Häussler S, Blankenfeldt W. 2009. Structure elucidation and preliminary assessment of hydrolase activity of PqsE, the Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS) response protein. Biochemistry 48:10298–10307. doi: 10.1021/bi900123j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A putative ligand produced by PqsE is not responsible for the PqsE-dependent regulation of the transcription of phzA1-lux. Cell-free supernatant(s) (final 30%) recovered from 18-h cultures was added to cultures of a rhlI::MrT7 ΔpqsE double mutant bearing a phzA1-lux reporter, and activity was measured after a 4-h incubation. The values are means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three replicates. Association with different letters represents statistical significance based on ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparison tests. Download FIG S1, PDF file, 0.1 MB (68.5KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Groleau et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Transcription of hcnABC requires PqsE in a lasR-negative background. (A) The β-galactosidase activity of an hcnA-lacZ reporter was measured in various backgrounds at different time points during growth. (B) A subset of data shown in panel A showing the activity in the lasR and lasR pqsE mutant backgrounds only. The values are means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three replicates. Download FIG S2, PDF file, 0.2 MB (166.8KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Groleau et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Effects of rhlI and rhlR overexpression on pyocyanin (PYO) production. The absorbance of supernatants from cultures at an OD600 of 4.5 was measured at 695 nm. The values are means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three replicates. ****, P < 0.0001; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; ns, not significant based on t tests. Download FIG S3, PDF file, 0.1 MB (48.3KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2020 Groleau et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.