Microbial adhesion and biofilm formation are usually studied using molecular and cellular biology assays, optical and electron microscopy, or laminar flow chamber experiments. Today, atomic force microscopy (AFM) represents a valuable addition to these approaches, enabling the measurement of forces involved in microbial adhesion at the single-molecule level. In this minireview, we discuss recent discoveries made applying state-of-the-art AFM techniques to microbial specimens in order to understand the strength and dynamics of adhesive interactions.

KEYWORDS: atomic force microscopy, cell adhesion, cell surface

ABSTRACT

Microbial adhesion and biofilm formation are usually studied using molecular and cellular biology assays, optical and electron microscopy, or laminar flow chamber experiments. Today, atomic force microscopy (AFM) represents a valuable addition to these approaches, enabling the measurement of forces involved in microbial adhesion at the single-molecule level. In this minireview, we discuss recent discoveries made applying state-of-the-art AFM techniques to microbial specimens in order to understand the strength and dynamics of adhesive interactions. These studies shed new light on the molecular mechanisms of adhesion and demonstrate an intimate relationship between force and function in microbial adhesins.

INTRODUCTION

Microbial pathogens (i.e., fungi, bacteria, and viruses) have the ubiquitous ability to adhere to biotic and abiotic surfaces (e.g., fomites, implants, catheters, and host cells) in environmental and clinical contexts (1). Prime examples are Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus strains involved in nosocomial infections (2) and mycobacteria that cause diseases like tuberculosis and leprosy. These species all rely on adhesion to biomaterials and host factors to initiate infection (3). Moreover, the vast majority of environmental microbial cells rapidly give up their floating planktonic lifestyle in an adhesion-dependent process to assemble into surface-associated communities called biofilms (4). In these structures the cells are protected from various environmental stresses like starvation, desiccation, antibiotics, and xenobiotics (5). So microbial cell adhesion has great medical, environmental, and industrial importance (2, 6).

Microbial cells feature a large variety of adhesion mechanisms involving physical properties of the cell surface, such as charge, hydrophobicity, and stiffness, as well as specific receptor-ligand binding mediated by adhesins and appendages (pili and curli). How these parameters lead to invasion and infection is a fascinating field that has benefited from the recent advent of ultrasensitive technologies (7, 8). Among these, atomic force microscopy (AFM) has proven to be a powerful tool to quantitatively probe the mechanical forces involved in cell adhesion while morphologically characterizing the cells (8). The heart of an AFM consists of a nanometer-sized tip attached to the end of a soft cantilever, which scans the sample in the x and y directions. Due to interactions between the tip and the sample, the cantilever bends vertically (z direction). This deflection is recorded via a laser beam focused on the cantilever and reflected onto a photodiode. Taking into account physical characteristics of the cantilever (sensitivity and spring constant), the exact force (in newtons) exerted by the tip on the sample can be determined. Raster scanning of the AFM tip across the sample, in either constant contact, intermittent contact, or noncontact mode (8), can provide very-high-resolution topographic images of the sample (on microbes, typical lateral resolution is in the range of ∼20 nm and vertical resolution is ∼0.1 to 1 nm). Moreover, in force spectroscopy, the tip is approached and retracted from the surface and the force-distance (FD) curves generated provide measurements of physical properties of the specimen, such as stiffness, elasticity, deformation, and adhesion. FD-based imaging makes it possible to map the spatial distribution of these properties on the nanoscale. Functionalization of the AFM probe with ligands allows probing of molecular interactions with single receptors (single-molecule force spectroscopy [SMFS]), e.g., between a single bacterial adhesin exposed on a living bacterium and a single extracellular matrix protein. Alternatively, attaching a single bacterial cell on the cantilever offers a means to probe force interactions between a single cell and a substrate (single-cell force spectroscopy [SCFS] [Fig. 1]). These various modes have paved the way for a detailed understanding of the interaction strength between microbes and their target surfaces.

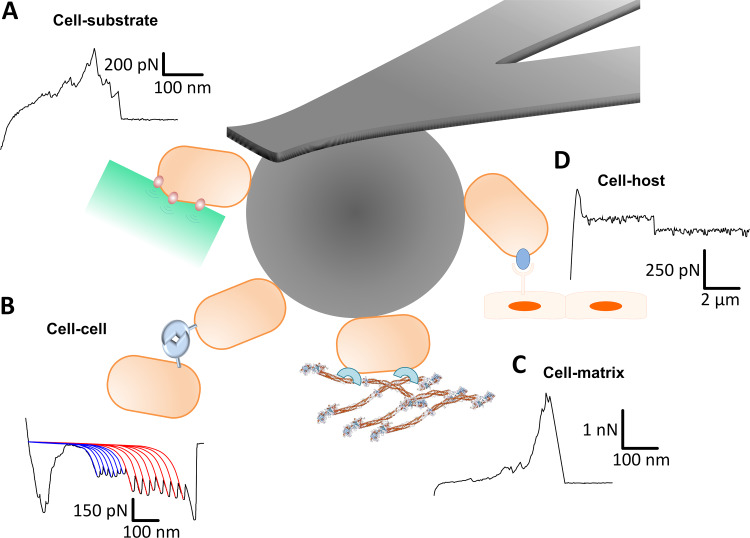

FIG 1.

Multifaceted use of single cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) to study microbial cell adhesion. (A) SCFS to measure interactions between cells and abiotic substrates. Shown is a characteristic adhesive curve obtained between a single Lactococcus plantarum cell and a model hydrophobic surface (116). (B) Homophilic binding between adhesins promotes cell-cell contacts. A typical force curve shows SasG-SasG interactions displaying sawtooth profiles fitted with the extensible worm-like-chain (WLC) model (49). (C) Staphylococcus cells bind with extreme strength to the extracellular matrix protein fibrinogen (Fg). A force curve is shown of the interaction between a single Staphylococcus epidermidis HB cell expressing SdrG and an Fg substrate (56). (D) SCFS measuring interactions between pathogens and their host cells. A representative force showing a typical force plateau resulting from pulling on Caco-2 cell plasma membrane tethers by Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG cells (41).

CELL ADHESION FORCES

Cell-substrate adhesion.

AFM has been instrumental in capturing the adhesive forces between pathogens and medically relevant abiotic surfaces, such as polymeric biomaterials (Fig. 1). SCFS revealed that large cell wall proteins from S. aureus are responsible for long-range (50-nm) attractive forces toward hydrophobic surfaces (9, 10). Large forces were measured between S. aureus and materials used in the dental practice, such as stainless steel, polyethylene, and polyvinyl chloride (11). The adhesion of Streptococcus mutans to different substratum surfaces was correlated with force-responsive changes in gene expression, providing insight into how emergent biofilm characteristics are triggered by quorum sensing (12). Saliva enhanced, but fluoride treatment reduced, the adhesion of streptococci to model enamel surfaces (13, 14). In the fungal context, Valotteau et al. identified three Epa proteins that mediate the adhesion of Candida species to hydrophobic and hydrophilic substrates (15). Besides SCFS, FD-based imaging with chemically modified tips was used to quantitatively map surface adhesive properties on living bacteria. Patchy hydrophobic nanodomains were observed on Acinetobacter venetianus and Rhodococcus erythropolis (16), while Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Aspergillus fumigatus exhibited homogenous hydrophobic surfaces (17–19). Mature cell walls of Aspergillus nidulans were less hydrophilic than growing tips and branch point junctions (20), consistent with variations in surface hydrophilicity as a function of cell wall composition (21). In the same line, Rhizobium leguminosarum showed an inverse relationship between surface hydrophilicity and mature biofilm formation (22). AFM has also shown its potential to assess antifouling and antiadhesive coatings, with the goal of preventing the initial step of biofilm formation on implanted biomaterials. For instance, polyzwitterionic polymer brushes were found to drastically reduce the force needed to detach Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (23). Insertion of cationic nanoclusters in such brushes also enhanced the removal of S. aureus (24). Two studies identified the antiadhesive properties of negatively charged polymer brushes against E. coli (25) and that of sophorolipid biosurfactants against both E. coli and S. aureus (26). AFM also demonstrated how the herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, which induced remodeling of the cell wall of Rhizobium leguminosarum, led to alterations in its surface hydrophobicity (27). Exposure of E. coli to 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid led to an oxidative stress response accompanied by increased surface hydrophilicity (28, 29), which showed a time dependency (30).

Gram-positive and Gram-negative appendages, such as pili and fimbriae, also adhere through nonspecific and specific interactions with surfaces (31). This confers functions like promoting interactions between bacteria of the same or different species, between bacteria and abiotic surfaces, or between bacteria and host tissues (Fig. 1) (32). Pili in some organisms also play a role in motility within biofilms, which is dependent upon interactions between them and the substratum (33). In Gram-negative bacteria, type I, type IV, and P pili elongate under force, giving rise to characteristic constant force plateaus (34–37). These pili, of which the subunits are held together through noncovalent interactions, can bear forces in the range of 250 pN (34), and multiple pili often work together to confer their force-dependent functions (38). In Gram-positive bacteria, pilus subunits are usually bound to each other via covalent bonds, allowing them to resist forces in excess of 500 pN (39, 40). Due to the covalent bonds, these pili behave like nanosprings under force (41, 42).

Cell-cell adhesion.

Microbial cells can adhere to each other using homophilic bonds between adhesins (Fig. 1). Examples are the aggregation mediated by the mycobacterial heparin-binding hemagglutinin adhesin of mycobacteria (43, 44), by the Burkholderia cenocepacia trimeric autotransporter adhesin (45), and by the Candida albicans Als adhesins (46, 47). In S. aureus, FnBPA proteins bind to each other in a Zn2+-dependent way with moderate forces, on the order of 150 pN (48), while SasG forms much more stable homophilic bonds, resisting forces of 500 pN (49). This suggests that bacteria have evolved specialized intercellular adhesion mechanisms that allow them either to detach from biofilms or to resist detachment when subjected to shear forces. Saccharomyces cerevisiae flocculins (50) and C. albicans Als adhesins (46, 51) use β-sheet interactions to support cell aggregation.

Cell-host interactions.

Adhesion to host tissues is the first step of infection for many pathogens (52). Several studies have brought detailed molecular insights into how adhesins specifically bind to host proteins, sometimes in a mechanoresponsive manner under shear stress (7, 53) (Fig. 1). Staphylococcal adhesins bind their target ligands with extremely strong forces (∼1 to 2 nN) that largely outperform classical binding forces. These include the collagen-binding protein Cna (54) and fibrinogen (Fg)-binding proteins SpsL (55) and SdrG (56–58). Such extreme forces structurally originate from the “dock, lock and latch” mechanism (or variations of it), which involves locking of the docked target peptide sequence by a N-terminal segment of the adhesin followed by latching of this complex on to a neighboring domain in the adhesin (59, 60). Steered molecular dynamics simulations in combination with AFM experiments showed that the extreme mechanical stability of the SdrG-Fg complex results from an intricate hydrogen bond network between the ligand peptide backbone and the adhesin (57, 61). When a strong mechanical load is applied in a direction that occurs under natural conditions (pulling force is applied at the C termini of both SdrG and Fg), an unbinding pathway is followed with a high energy barrier (58). Conversely, the unbinding pathways that would be followed under thermal unbinding (at equilibrium) or when weak mechanical loads are applied exhibit lower energy barriers (58). Such “catch” bonds (62) are proposed to exhibit longer lifetimes than their antonymous “slip” bonds, which is very useful to pathogens that need to stay adhered to their host-target tissues under hydrodynamic forces (58). AFM has provided evidence for the existence of catch bonds in ClfA, ClfB, and SpA (63–65), revealing that their binding strength is considerably increased by mechanical tension. The proposed mechanism involves force-induced conformational changes in the adhesins, from a weakly binding state to a strongly binding state, and explains how staphylococci can resist physical stresses such as hydrodynamic shear forces. Similarly, force-induced conformational changes in yeast flocculins (50) and Als adhesins (46, 51) trigger β-sheet interactions between amyloid sequences that strengthen cell aggregation.

Adhesive interactions between single microbes and host cells have also been studied (Fig. 1). Early examples include the heparin-binding hemagglutinin adhesin, which contributes to adhesion of mycobacteria to pneumocytes (66), and the Listeria monocytogenes invasion protein InlB, which supports adhesion to the Met receptor tyrosine kinase (67). More recently, strong FnBPA-Fn-integrin interactions between living S. aureus and endothelial cells were shown to involve an activation mechanism in which FnBPA binding to Fn stimulates the exposure of cryptic integrin-binding sites in Fn (68). In the skin context, it was found that decreases in the levels of natural moisturizing factor in cultured corneocytes increased S. aureus adhesion via the ClfB adhesin (65). Viela et al. investigated the Fg-dependent interaction between S. aureus ClfA and the endothelial cell integrin αVβ3 (63) and revealed that the ClfA-Fg-αVβ3 ternary complex sustains very strong forces (∼800 pN).

Adhesin clustering.

Another pertinent question is whether microbes express their adhesins homogenously or whether these form nanodomains capable of enhancing adhesion. FD-based imaging detected such clustering in S. aureus for various adhesins, including FnBPs, SdrG, ClfA, ClfB, SpA, and SpsL (48, 64, 69, 70). It has been suggested that protein clustering on the cell surface may favor adhesion through multivalency. In the case of FnBP-Fn interactions, cluster bonds involving ∼10 or ∼80 proteins in parallel were reported for bloodstream isolates from patients with infected cardiovascular implants (71). Heterogenous clusters of rough lipopolysaccharide were observed on Brucella abortus cells (72), evidence that bacteria compartmentalize their surfaces for function. Notably, C. albicans was observed to redistribute Als5p adhesins into nanodomains in response to mechanical stimuli (46), suggesting that the pathogen is capable of actively responding to physical stresses in favor of adhesion.

Cell adhesion and antimicrobial therapy.

The effect of antimicrobials on cell surface properties has also been investigated. Exposure of C. albicans to the antifungal drug caspofungin induced overexpression of Als adhesins, which correlated with increased cell surface roughness, decreased stiffness, and increased hydrophobicity (73, 74). In the case of mycobacteria, treatment with several classes of antibiotics that target the synthesis of different components of their cell envelope also lead to dramatic alterations in their surface hydrophobicity (18). More recently, Laskowski et al. showed that although ampicillin increased surface roughness in the Gram-positive Bacillus subtilis and Gram-negative E. coli, only B. subtilis had altered adhesion (75). The effect of antibiotics on bacterial adhesion may thus be considered in future AFM studies focusing on antimicrobial mechanisms. Another exciting avenue for AFM is in the detection of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains, especially in the climate of increased drug resistance. Longo et al. demonstrated that bacterial adhesion to sensitive cantilevers causes their deflection to fluctuate, allowing the ability to distinguish between metabolically active and dead bacteria for the detection of antibiotic-resistant strains within minutes (76).

Because pathogens are becoming more and more resistant to antibiotics, it is becoming more and more urgent to discover new antimicrobial therapies. Antiadhesive agents capable of blocking the adhesion of pathogens to host tissues and biomaterials are an attractive alternative to classical antimicrobials (77). In early work, the Camesano team unraveled the antiadhesive activity of cranberry juice that targets E. coli fimbriae, effectively inhibiting their adhesion to abiotic surfaces and uroepithelial cells (78–80). AFM has been used to assess the blocking activity of antiadhesion compounds, such as peptides and antibodies. The capacity of glycofullerenes to interact with E. coli fimbriae and block their adhesion to mannose surfaces was quantified and the underlying mechanism revealed (81), opening new avenues for further studies into innovative treatments of intestinal colonization. Likewise, plant-based antifungals increased the surface hydrophilicity of C. albicans (82). AFM studies have also emphasized the antiadhesion potential of peptides and antibodies. Monoclonal antibodies acting as competitive inhibitors against Cna showed great efficiency in blocking S. aureus adhesion to collagen surfaces (54). A similar competitive inhibition was observed for a peptide derived from β-neurexin, which efficiently blocked homophilic SdrC interactions in S. aureus (83).

NEW TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

Fast single-cell manipulations.

Fluidic force microscopy (FluidFM) uses microchanneled AFM cantilevers connected to a pump through a microfluidic system (84). Such hollow probes offer possibilities like extracting or injecting material from or into mammalian cells and capturing single microbial cells by applying negative pressure to the aperture of the tip (85, 86). Hence, the technology makes it possible to prepare single cell probes for SCFS in a faster way than classical approaches (87). Therefore, FluidFM was used to detect hydrophobic adhesive forces as high as 50 nN among a large collection of bacteria, demonstrating its ease of use and applicability, especially when very large forces are of interest (88). As adhesion between the cell and the probe is reversible, a single bacterial cell can be picked up, transferred to a region of interest within the experimental setup, and released. This was successfully applied to isolate single bacteriochlorophyll-producing bacteria from a mixed population of leaf microbiota (89). Dehullu et al. used FluidFM to study cell-cell adhesion in C. albicans and found that amyloid sequences of the Als adhesin play an important role (47, 90). Although it shows great promise, we point out that SCFS-based FluidFM is still in its infancy and some caveats exist, such as the high stiffness of the cantilevers, which precludes precise measurements of smaller forces in the range of ∼100 pN.

High-speed molecular and cellular imaging.

During the past decade, advances have been made in the development of imaging modes with enhanced spatial and temporal resolutions. Classical topographic imaging is slow, meaning that it takes minutes to record an image (91). However, high-speed AFM (HS-AFM) instruments now enable researchers to reach millisecond resolution, owing to the use of small cantilevers and improved electronics (92). Even if it has not yet been established for studying cell adhesion, HS-AFM has potential in microbiology, allowing the filming of biological processes with molecular resolution without any staining (93). By way of example, HS-AFM was used to film real-time conformational changes in several bacterial integral membrane proteins, including the F1-ATPase rotary motor protein (94), an aspartate-sodium symporter (95), a pH-sensitive ion channel (96), and an ATP-dependent protein disaggregation machine (97). Recently, HS-AFM tracked the dynamic oligomerization of immunoglobulin G (IgG) on lipid membranes (98). Until now, the technology has been mainly limited to studying proteins in flat two-dimensional (2D) crystals or in model membranes because of technical limitations related to the large curvatures and roughness of living cells. However, several recent studies have addressed these issues, leading to the visualization of outer membrane proteins in curved membranes, including on living bacterial cells (98–101). Nievergelt et al. developed a new type of HS-AFM, called photothermal off-resonance tapping AFM (102), which allowed real-time, simultaneous nanomechanical and topographic imaging of B. subtilis cells as their walls were degraded by lysozyme (103). This strongly suggests that HS-AFM might soon be able to capture dynamic molecular events on pathogens, in relation with adhesion functions.

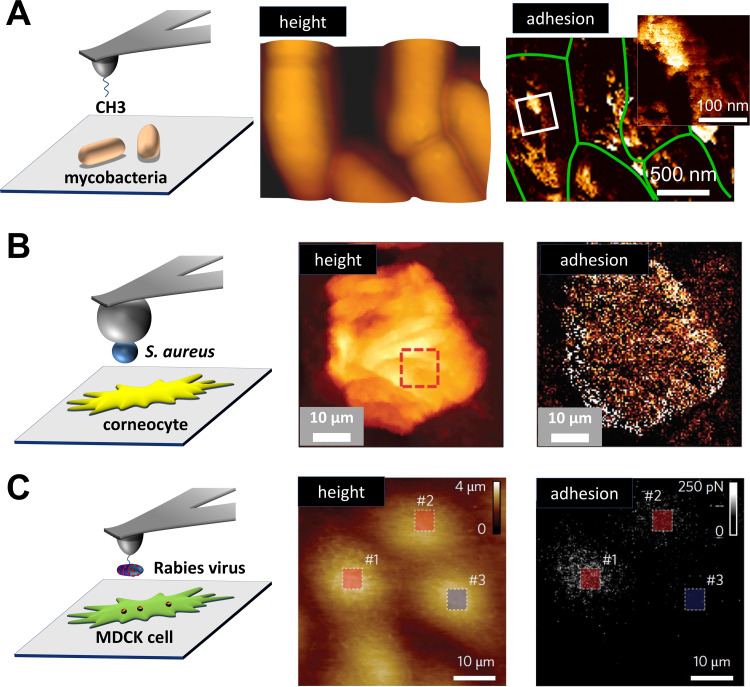

Another grand challenge is the application of FD curve-based multiparametric imaging for the fast structural and physical mapping of living cells (104). Force volume mode, in which arrays of force curves are recorded across the sample, has been extensively used to study protein distributions on bacterial cell envelopes. They have provided valuable insights on adsorption of bacteriophages (105, 106), on docking of motorized extracytoplasmic appendages such as pili (34, 41, 42) and on clustering of adhesins (63, 64, 69). Nevertheless, FV suffers from low imaging speed and resolution; i.e., it takes about 30 min to obtain a 32- by 32-pixel image. The advent of multiparametric imaging, such as peak force tapping (PFT) and quantitative imaging (QI), has enabled simultaneous imaging of the structural, chemical, and biophysical properties of living cells at higher spatiotemporal resolutions (91, 104). The multiparametric imaging toolbox has been instrumental in probing ligand-receptor bonds and mapping epitopes. A nickel-functionalized tip was used to locate and number the binding events of His-tagged bacteriorhodopsin on purple membranes of halobacteria at subnanometer resolution (107), to characterize its folding-unfolding state, and to draw a cartography of molecular interactions (75). QI and PFT have revealed the scaffolding nanostructures that cohere cable bacteria into millimeter-scale filaments (108), the physicomechanical damages electromagnetic stresses inflicted on cell walls (109), the localization of bacteriophage extrusion sites on infected bacteria (110), the organization of C. albicans mannoproteins into nanodomains (111), and the presence of hydrophobic nanodomains defined by glycopeptidolipids in mycobacteria (112) (Fig. 2A). QI was also used in the context of biofilm formation and showed the effect of metal ions on cell wall stiffness and adhesin pattern (49). Zn2+ cations enhanced the cohesion of the S. aureus cell wall, which promoted the extension of SasG, an adhesin that mediates homophilic interactions and cell-cell contact in biofilms, beyond masking surface components. As biofilms are dense bacterial communities highly resistant to antibiotics and chemical treatments, these results might help find new therapies to dismantle the biofilm matrix or prevent cell-cell junctions to form. An exciting approach for adhesion studies is to perform SCFS using a multiparametric mode. Formosa-Dague et al. used QI with single bacterial probes to study S. aureus adhesion to human skin cells (corneocytes) allowing mapping of adhesin-ligand contacts all over these cells with high spatiotemporal resolution (113) (Fig. 2B). Lastly, PFT allowed nanomechanical mapping of viral envelope glycoprotein binding to cognate receptors on host mammalian cells within the first millisecond of contact (117) (Fig. 2C). The data obtained allowed contouring the free energy landscape of the interaction. From this, the dynamics of the interaction could be determined, which showed that positive allosteric modulation led to rapid occupancy of the three binding sites of the glycoprotein. Using a similar approach, the mucin-like region of viral envelope glycoproteins was shown to play an important role in regulating the affinity, type, and number of glycoproteins that participate in viral interactions with cellular glycosaminoglycans (114). Similarly, a new mechanism was discovered whereby the herpesvirus glycoprotein negatively regulates initiation of viral binding to heparan sulfate through its effect on the valency of the interaction (115).

FIG 2.

Fast multiparametric imaging leads the way. (A) Fast chemical microscopy (QI with hydrophobic tips) reveals hydrophobic and hydrophilic nanodomains with unprecedented resolution on mycobacterial cells. Adapted from reference 112 with permission of the publisher. (B) QI used in combination with SCFS and single S. aureus cell probes versus corneocytes cells. Adapted from reference 113 with permission of the publisher. (C) PFT mode with a virus-functionalized tip probing a host cell. Adapted from reference 117 with permission of the publisher. For all panels, on the left are cartoons of the different multiparametric imaging approaches used. The middle portions show height images, and the right portions show corresponding adhesion maps. In panel A, a zoom of a high-resolution adhesion map recorded on one cell is also shown.

CONCLUSION

AFM has demonstrated that adhesins are engaged in a wealth of molecular interactions, with mechanical strengths ranging from a few dozen piconewtons to several nanonewtons. Perhaps the most exciting discovery of the recent years is that staphylococcal adhesins engage in ultrastrong catch bond interactions that are much stronger than any noncovalent biological interaction studied so far. These interactions are activated by mechanical force, offering the pathogens an elegant means to withstand physiological shear forces during adhesion and colonization. Other major achievements are the measurements of homophilic binding forces involved in cell aggregation, of the adhesive and mechanical responses of bacterial pili when interacting with a substrate, and of the interaction forces between pathogens and either host proteins or host cells. These novel insights open up new avenues for the identification of small inhibitors to prevent pathogen adhesion and invasion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work at UCLouvain was supported by the Excellence of Science-EOS program (grant number 30550343), the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement number 693630), the FNRS-WELBIO (grant number WELBIO-CR-2015A-05), the National Fund for Scientific Research (FNRS), and the Research Department of the Communauté française de Belgique (Concerted Research Action). Y.F.D. is Research Director at the FNRS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arciola CR, Campoccia D, Montanaro L. 2018. Implant infections: adhesion, biofilm formation and immune evasion. Nat Rev Microbiol 16:397–409. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0019-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stones DH, Krachler AM. 2016. Against the tide: the role of bacterial adhesion in host colonization. Biochem Soc Trans 44:1571–1580. doi: 10.1042/BST20160186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flemming H-C, Wuertz S. 2019. Bacteria and archaea on Earth and their abundance in biofilms. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:247–260. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolter R, Greenberg EP. 2006. The superficial life of microbes. Nature 441:300–302. doi: 10.1038/441300a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrett TR, Bhakoo M, Zhang Z. 2008. Bacterial adhesion and biofilms on surfaces. Prog Nat Sci 18:1049–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.pnsc.2008.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dufrêne YF, Persat A. 2020. Mechanomicrobiology: how bacteria sense and respond to forces. Nat Rev Microbiol 18:227–240. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0314-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao J, Dufrêne YF. 2016. Optical and force nanoscopy in microbiology. Nat Microbiol 1:16186. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thewes N, Loskill P, Jung P, Peisker H, Bischoff M, Herrmann M, Jacobs K. 2014. Hydrophobic interaction governs unspecific adhesion of staphylococci: a single cell force spectroscopy study. Beilstein J Nanotechnol 5:1501–1512. doi: 10.3762/bjnano.5.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thewes N, Thewes A, Loskill P, Peisker H, Bischoff M, Herrmann M, Santen L, Jacobs K. 2015. Stochastic binding of Staphylococcus aureus to hydrophobic surfaces. Soft Matter 11:8913–8919. doi: 10.1039/c5sm00963d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merghni A, Bekir K, Kadmi Y, Dallel I, Janel S, Bovio S, Barois N, Lafont F, Mastouri M. 2017. Adhesiveness of opportunistic Staphylococcus aureus to materials used in dental office: in vitro study. Microb Pathog 103:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang C, Hou J, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ, Ren Y. 2019. Emergent properties in Streptococcus mutans biofilms are controlled through adhesion force sensing by initial colonizers. mBio 10:e01908-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01908-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loskill P, Zeitz C, Grandthyll S, Thewes N, Müller F, Bischoff M, Herrmann M, Jacobs K. 2013. Reduced adhesion of oral bacteria on hydroxyapatite by fluoride treatment. Langmuir 29:5528–5533. doi: 10.1021/la4008558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spengler C, Thewes N, Nolle F, Faidt T, Umanskaya N, Hannig M, Bischoff M, Jacobs K. 2017. Enhanced adhesion of Streptococcus mutans to hydroxyapatite after exposure to saliva. J Mol Recognit 30:e2615. doi: 10.1002/jmr.2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valotteau C, Prystopiuk V, Cormack BP, Dufrêne YF. 2019. Atomic force microscopy demonstrates that Candida glabrata uses three Epa proteins to mediate adhesion to abiotic surfaces. mSphere 4:e00277-19. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00277-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorobantu LS, Bhattacharjee S, Foght JM, Gray MR. 2008. Atomic force microscopy measurement of heterogeneity in bacterial surface hydrophobicity. Langmuir 24:4944–4951. doi: 10.1021/la7035295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alsteens D, Dague E, Rouxhet PG, Baulard AR, Dufrêne YF. 2007. Direct measurement of hydrophobic forces on cell surfaces using AFM. Langmuir 23:11977–11979. doi: 10.1021/la702765c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alsteens D, Verbelen C, Dague E, Raze D, Baulard AR, Dufrêne YF. 2008. Organization of the mycobacterial cell wall: a nanoscale view. Pflugers Arch 456:117–125. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0386-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dague E, Alsteens D, Latgé J-P, Verbelen C, Raze D, Baulard AR, Dufrêne YF. 2007. Chemical force microscopy of single live cells. Nano Lett 7:3026–3030. doi: 10.1021/nl071476k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma H, Snook LA, Kaminskyj SGW, Dahms T. 2005. Surface ultrastructure and elasticity in growing tips and mature regions of Aspergillus hyphae describe wall maturation. Microbiology 151:3679–3688. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28328-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paul BC, El-Ganiny AM, Abbas M, Kaminskyj SGW, Dahms T. 2011. Quantifying the importance of galactofuranose in Aspergillus nidulans hyphal wall surface organization by atomic force microscopy. Eukaryot Cell 10:646–653. doi: 10.1128/EC.00304-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong J, Signo KSL, Vanderlinde EM, Yost CK, Dahms T. 2011. Atomic force microscopy of a ctpA mutant in Rhizobium leguminosarum reveals surface defects linking CtpA function to biofilm formation. Microbiology 157:3049–3058. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.051045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez-Emmenegger C, Janel S, Pereira A, de los S, Bruns M, Lafont F. 2015. Quantifying bacterial adhesion on antifouling polymer brushes via single-cell force spectroscopy. Polym Chem 6:5740–5751. doi: 10.1039/C5PY00197H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang B, Jiang Y, Rotello VM, Nüsslein K, Santore MM. 2014. Easy come easy go: surfaces containing immobilized nanoparticles or isolated polycation chains facilitate removal of captured Staphylococcus aureus by retarding bacterial bond maturation. ACS Nano 8:1180–1190. doi: 10.1021/nn405845y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oh YJ, Khan ES, Campo AD, Hinterdorfer P, Li B. 2019. Nanoscale characteristics and antimicrobial properties of (SI-ATRP)-seeded polymer brush surfaces. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 11:29312–29319. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b09885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valotteau C, Baccile N, Humblot V, Roelants S, Soetaert W, Stevens CV, Dufrêne YF. 2019. Nanoscale antiadhesion properties of sophorolipid-coated surfaces against pathogenic bacteria. Nanoscale Horiz 4:975–982. doi: 10.1039/C9NH00006B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhat SV, Booth SC, McGrath SGK, Dahms T. 2014. Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae 3841 adapts to 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid with “auxin-like” morphological changes, cell envelope remodeling and upregulation of central metabolic pathways. PLoS One 10:e0123813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhat SV, Booth SC, Vantomme EAN, Afroj S, Yost CK, Dahms T. 2015. Oxidative stress and metabolic perturbations in Escherichia coli exposed to sublethal levels of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Chemosphere 135:453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhat SV, Sultana T, Körnig A, McGrath S, Shahina Z, Dahms T. 2018. Correlative atomic force microscopy quantitative imaging-laser scanning confocal microscopy quantifies the impact of stressors on live cells in real time. Sci Rep 8:8305. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26433-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhat SV, Kamencic B, Körnig A, Shahina Z, Dahms T. 2018. Exposure to sub-lethal 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid arrests cell division and alters cell surface properties in Escherichia coli. Front Microbiol 9:44. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lillington J, Geibel S, Waksman G. 2014. Biogenesis and adhesion of type 1 and P pili. Biochim Biophys Acta 1840:2783–2793. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hospenthal MK, Costa TRD, Waksman G. 2017. A comprehensive guide to pilus biogenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 15:365–379. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordon VD, Wang L. 2019. Bacterial mechanosensing: the force will be with you, always. J Cell Sci 132:jcs227694. doi: 10.1242/jcs.227694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beaussart A, Baker AE, Kuchma SL, El-Kirat-Chatel S, O'Toole GA, Dufrêne YF. 2014. Nanoscale adhesion forces of Pseudomonas aeruginosa type IV pili. ACS Nano 8:10723–10733. doi: 10.1021/nn5044383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forero M, Yakovenko O, Sokurenko EV, Thomas WE, Vogel V. 2006. Uncoiling mechanics of Escherichia coli type I fimbriae are optimized for catch bonds. PLoS Biol 4:e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lugmaier RA, Schedin S, Kühner F, Benoit M. 2008. Dynamic restacking of Escherichia coli P-pili. Eur Biophys J 37:111–120. doi: 10.1007/s00249-007-0183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller E, Garcia T, Hultgren S, Oberhauser AF. 2006. The mechanical properties of E. coli type 1 pili measured by atomic force microscopy techniques. Biophys J 91:3848–3856. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.088989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Biais N, Ladoux B, Higashi D, So M, Sheetz M. 2008. Cooperative retraction of bundled type IV pili enables nanonewton force generation. PLoS Biol 6:e87. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Echelman DJ, Alegre-Cebollada J, Badilla CL, Chang C, Ton-That H, Fernández JM. 2016. CnaA domains in bacterial pili are efficient dissipaters of large mechanical shocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:2490–2495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522946113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alegre-Cebollada J, Badilla CL, Fernández JM. 2010. Isopeptide bonds block the mechanical extension of pili in pathogenic Streptococcus pyogenes. J Biol Chem 285:11235–11242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sullan RMA, Beaussart A, Tripathi P, Derclaye S, El-Kirat-Chatel S, Li JK, Schneider Y-J, Vanderleyden J, Lebeer S, Dufrêne YF. 2014. Single-cell force spectroscopy of pili-mediated adhesion. Nanoscale 6:1134–1143. doi: 10.1039/c3nr05462d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tripathi P, Beaussart A, Alsteens D, Dupres V, Claes I, von Ossowski I, de Vos WM, Palva A, Lebeer S, Vanderleyden J, Dufrêne YF. 2013. Adhesion and nanomechanics of pili from the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. ACS Nano 7:3685–3697. doi: 10.1021/nn400705u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dupres V, Menozzi FD, Locht C, Clare BH, Abbott NL, Cuenot S, Bompard C, Raze D, Dufrêne YF. 2005. Nanoscale mapping and functional analysis of individual adhesins on living bacteria. Nat Methods 2:515–520. doi: 10.1038/nmeth769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verbelen C, Raze D, Dewitte F, Locht C, Dufrêne YF. 2007. Single-molecule force spectroscopy of mycobacterial adhesin-adhesin interactions. J Bacteriol 189:8801–8806. doi: 10.1128/JB.01299-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.El-Kirat-Chatel S, Mil-Homens D, Beaussart A, Fialho AM, Dufrêne YF. 2013. Single-molecule atomic force microscopy unravels the binding mechanism of a Burkholderia cenocepacia trimeric autotransporter adhesin. Mol Microbiol 89:649–659. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alsteens D, Garcia MC, Lipke PN, Dufrêne YF. 2010. Force-induced formation and propagation of adhesion nanodomains in living fungal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:20744–20749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013893107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dehullu J, Valotteau C, Herman-Bausier P, Garcia-Sherman M, Mittelviefhaus M, Vorholt JA, Lipke PN, Dufrêne YF. 2019. Fluidic force microscopy demonstrates that homophilic adhesion by Candida albicans Als proteins is mediated by amyloid bonds between cells. Nano Lett 19:3846–3853. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b01010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Herman-Bausier P, El-Kirat-Chatel S, Foster TJ, Geoghegan JA, Dufrêne YF. 2015. Staphylococcus aureus fibronectin-binding protein A mediates cell-cell adhesion through low-affinity homophilic bonds. mBio 6:e00413-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00413-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Formosa-Dague C, Speziale P, Foster TJ, Geoghegan JA, Dufrêne YF. 2016. Zinc-dependent mechanical properties of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm-forming surface protein SasG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:410–415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519265113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan CXJ, El-Kirat-Chatel S, Joseph IG, Jackson DN, Ramsook CB, Dufrêne YF, Lipke PN. 2016. Force sensitivity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae flocculins. mSphere 1:e00128-16. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00128-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garcia MC, Lee JT, Ramsook CB, Alsteens D, Dufrêne YF, Lipke PN. 2011. A role for amyloid in cell aggregation and biofilm formation. PLoS One 6:e17632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh B, Fleury C, Jalalvand F, Riesbeck K. 2012. Human pathogens utilize host extracellular matrix proteins laminin and collagen for adhesion and invasion of the host. FEMS Microbiol Rev 36:1122–1180. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Casillas-Ituarte NN, Cruz CHB, Lins RD, DiBartola AC, Howard J, Liang X, Höök M, Viana IFT, Sierra-Hernández MR, Lower SK. 2017. Amino acid polymorphisms in the fibronectin-binding repeats of fibronectin-binding protein A affect bond strength and fibronectin conformation. J Biol Chem 292:8797–8810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.786012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Herman-Bausier P, Valotteau C, Pietrocola G, Rindi S, Alsteens D, Foster TJ, Speziale P, Dufrêne YF. 2016. Mechanical strength and inhibition of the Staphylococcus aureus collagen-binding protein Cna. mBio 7:e01529-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01529-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pickering AC, Vitry P, Prystopiuk V, Garcia B, Höök M, Schoenebeck J, Geoghegan JA, Dufrêne YF, Fitzgerald JR. 2019. Host-specialized fibrinogen-binding by a bacterial surface protein promotes biofilm formation and innate immune evasion. PLoS Pathog 15:e1007816. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Herman P, El-Kirat-Chatel S, Beaussart A, Geoghegan JA, Foster TJ, Dufrêne YF. 2014. The binding force of the staphylococcal adhesin SdrG is remarkably strong. Mol Microbiol 93:356–368. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Milles LF, Schulten K, Gaub HE, Bernardi RC. 2018. Molecular mechanism of extreme mechanostability in a pathogen adhesin. Science 359:1527–1533. doi: 10.1126/science.aar2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Milles LF, Gaub HE. 2020. Extreme mechanical stability in protein complexes. Curr Opin Struct Biol 60:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2019.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bowden MG, Heuck AP, Ponnuraj K, Kolosova E, Choe D, Gurusiddappa S, Narayana SVL, Johnson AE, Höök M. 2008. Evidence for the “dock, lock, and latch” ligand binding mechanism of the staphylococcal microbial surface component recognizing adhesive matrix molecules (MSCRAMM) SdrG. J Biol Chem 283:638–647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706252200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ponnuraj K, Bowden MG, Davis S, Gurusiddappa S, Moore D, Choe D, Xu Y, Hook M, Narayana S. 2003. A “dock, lock, and latch” structural model for a staphylococcal adhesin binding to fibrinogen. Cell 115:217–228. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00809-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Herman-Bausier P, Dufrêne YF. 2018. Force matters in hospital-acquired infections. Science 359:1464–1465. doi: 10.1126/science.aat3764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sokurenko EV, Vogel V, Thomas WE. 2008. Catch-bond mechanism of force-enhanced adhesion: counterintuitive, elusive, but…widespread? Cell Host Microbe 4:314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Viela F, Speziale P, Pietrocola G, Dufrêne YF. 2019. Mechanostability of the fibrinogen bridge between staphylococcal surface protein ClfA and endothelial cell integrin αVβ3. Nano Lett 19:7400–7410. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b03080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Viela F, Prystopiuk V, Leprince A, Mahillon J, Speziale P, Pietrocola G, Dufrêne YF. 2019. Binding of Staphylococcus aureus protein A to von Willebrand factor is regulated by mechanical force. mBio 10:e00555-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00555-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Feuillie C, Vitry P, McAleer MA, Kezic S, Irvine AD, Geoghegan JA, Dufrêne YF. 2018. Adhesion of Staphylococcus aureus to corneocytes from atopic dermatitis patients is controlled by natural moisturizing factor levels. mBio 9:e01184-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01184-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dupres V, Verbelen C, Raze D, Lafont F, Dufrêne YF. 2009. Force spectroscopy of the interaction between mycobacterial adhesins and heparan sulphate proteoglycan receptors. Chemphyschem 10:1672–1675. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mostowy S, Janel S, Forestier C, Roduit C, Kasas S, Pizarro-Cerdá J, Cossart P, Lafont F. 2011. A role for septins in the interaction between the Listeria monocytogenes invasion protein InlB and the Met receptor. Biophys J 100:1949–1959. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Prystopiuk V, Feuillie C, Herman-Bausier P, Viela F, Alsteens D, Pietrocola G, Speziale P, Dufrêne YF. 2018. Mechanical forces guiding Staphylococcus aureus cellular invasion. ACS Nano 12:3609–3622. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b00716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Herman-Bausier P, Labate C, Towell AM, Derclaye S, Geoghegan JA, Dufrêne YF. 2018. Staphylococcus aureus clumping factor A is a force-sensitive molecular switch that activates bacterial adhesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:5564–5569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718104115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vitry P, Valotteau C, Feuillie C, Bernard S, Alsteens D, Geoghegan JA, Dufrêne YF. 2017. Force-induced strengthening of the interaction between Staphylococcus aureus clumping factor B and loricrin. mBio 8:e01748-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01748-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Casillas-Ituarte NN, Lower BH, Lamlertthon S, Fowler VG, Lower SK. 2012. Dissociation rate constants of human fibronectin binding to fibronectin-binding proteins on living Staphylococcus aureus isolated from clinical patients. J Biol Chem 287:6693–6701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.285692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vassen V, Valotteau C, Feuillie C, Formosa-Dague C, Dufrêne YF, De Bolle X. 2019. Localized incorporation of outer membrane components in the pathogen Brucella abortus. EMBO J 38:e100323. doi: 10.15252/embj.2018100323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beaussart A, Alsteens D, El-Kirat-Chatel S, Lipke PN, Kucharíková S, Van Dijck P, Dufrêne YF. 2012. Single-molecule imaging and functional analysis of Als adhesins and mannans during Candida albicans morphogenesis. ACS Nano 6:10950–10964. doi: 10.1021/nn304505s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.El-Kirat-Chatel S, Beaussart A, Alsteens D, Jackson DN, Lipke PN, Dufrêne YF. 2013. Nanoscale analysis of caspofungin-induced cell surface remodelling in Candida albicans. Nanoscale 5:1105–1115. doi: 10.1039/c2nr33215a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Laskowski PR, Pfreundschuh M, Stauffer M, Ucurum Z, Fotiadis D, Müller DJ. 2017. High-resolution imaging and multiparametric characterization of native membranes by combining confocal microscopy and an atomic force microscopy-based toolbox. ACS Nano 11:8292–8301. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b03456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Longo G, Alonso-Sarduy L, Rio LM, Bizzini A, Trampuz A, Notz J, Dietler G, Kasas S. 2013. Rapid detection of bacterial resistance to antibiotics using AFM cantilevers as nanomechanical sensors. Nat Nanotechnol 8:522–526. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Geoghegan JA, Foster TJ, Speziale P, Dufrêne YF. 2017. Live-cell nanoscopy in antiadhesion therapy. Trends Microbiol 25:512–514. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu Y, Pinzón-Arango PA, Gallardo-Moreno AM, Camesano TA. 2010. Direct adhesion force measurements between E. coli and human uroepithelial cells in cranberry juice cocktail. Mol Nutr Food Res 54:1744–1752. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pinzón-Arango PA, Liu Y, Camesano TA. 2009. Role of cranberry on bacterial adhesion forces and implications for Escherichia coli-uroepithelial cell attachment. J Med Food 12:259–270. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2008.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tao Y, Pinzón-Arango PA, Howell AB, Camesano TA. 2011. Oral consumption of cranberry juice cocktail inhibits molecular-scale adhesion of clinical uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Med Food 14:739–745. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2010.0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beaussart A, Abellán-Flos M, El-Kirat-Chatel S, Vincent SP, Dufrêne YF. 2016. Force nanoscopy as a versatile platform for quantifying the activity of antiadhesion compounds targeting bacterial pathogens. Nano Lett 16:1299–1307. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b04689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shahina Z, El-Ganiny AM, Minion J, Whiteway M, Sultana T, Dahms T. 2018. Cinnamomum zeylanicum bark essential oil induces cell wall remodelling and spindle defects in Candida albicans. Fungal Biol Biotechnol 5:3. doi: 10.1186/s40694-018-0046-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Feuillie C, Formosa-Dague C, Hays LMC, Vervaeck O, Derclaye S, Brennan MP, Foster TJ, Geoghegan JA, Dufrêne YF. 2017. Molecular interactions and inhibition of the staphylococcal biofilm-forming protein SdrC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:3738–3743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616805114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Meister A, Gabi M, Behr P, Studer P, Vörös J, Niedermann P, Bitterli J, Polesel-Maris J, Liley M, Heinzelmann H, Zambelli T. 2009. FluidFM: combining atomic force microscopy and nanofluidics in a universal liquid delivery system for single cell applications and beyond. Nano Lett 9:2501–2507. doi: 10.1021/nl901384x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Guillaume-Gentil O, Potthoff E, Ossola D, Franz CM, Zambelli T, Vorholt JA. 2014. Force-controlled manipulation of single cells: from AFM to FluidFM. Trends Biotechnol 32:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guillaume‐Gentil O, Mittelviefhaus M, Dorwling‐Carter L, Zambelli T, Vorholt JA. 2018. FluidFM applications in single-cell biology, p 325–354. In Delamarche E, Kaigala GV (ed), Open-space microfluidics: concepts, implementations, applications. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Weinheim, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Potthoff E, Ossola D, Zambelli T, Vorholt JA. 2015. Bacterial adhesion force quantification by fluidic force microscopy. Nanoscale 7:4070–4079. doi: 10.1039/c4nr06495j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mittelviefhaus M, Müller DB, Zambelli T, Vorholt JA. 2019. A modular atomic force microscopy approach reveals a large range of hydrophobic adhesion forces among bacterial members of the leaf microbiota. ISME J 13:1878–1882. doi: 10.1038/s41396-019-0404-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stiefel P, Zambelli T, Vorholt JA. 2013. Isolation of optically targeted single bacteria by application of fluidic force microscopy to aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs from the phyllosphere. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:4895–4905. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01087-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dehullu J, Vorholt JA, Lipke PN, Dufrêne YF. 2019. Fluidic force microscopy captures amyloid bonds between microbial cells. Trends Microbiol 27:728–730. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dufrêne YF, Ando T, Garcia R, Alsteens D, Martinez-Martin D, Engel A, Gerber C, Müller DJ. 2017. Imaging modes of atomic force microscopy for application in molecular and cell biology. Nat Nanotechnol 12:295–307. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2017.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ando T. 2018. High-speed atomic force microscopy and its future prospects. Biophys Rev 10:285–292. doi: 10.1007/s12551-017-0356-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ando T, Uchihashi T, Scheuring S. 2014. Filming biomolecular processes by high-speed atomic force microscopy. Chem Rev 114:3120–3188. doi: 10.1021/cr4003837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Uchihashi T, Iino R, Ando T, Noji H. 2011. High-speed atomic force microscopy reveals rotary catalysis of rotorless F1-ATPase. Science 333:755–758. doi: 10.1126/science.1205510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ruan Y, Miyagi A, Wang X, Chami M, Boudker O, Scheuring S. 2017. Direct visualization of glutamate transporter elevator mechanism by high-speed AFM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:1584–1588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616413114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ruan Y, Kao K, Lefebvre S, Marchesi A, Corringer P-J, Hite RK, Scheuring S. 2018. Structural titration of receptor ion channel GLIC gating by HS-AFM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:10333–10338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1805621115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Uchihashi T, Watanabe Y, Nakazaki Y, Yamasaki T, Watanabe H, Maruno T, Ishii K, Uchiyama S, Song C, Murata K, Iino R, Ando T. 2018. Dynamic structural states of ClpB involved in its disaggregation function. Nat Commun 9:2147. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04587-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Strasser J, de Jong RN, Beurskens FJ, Schuurman J, Parren PWHI, Hinterdorfer P, Preiner J. 2020. Weak fragment crystallizable (Fc) domain interactions drive the dynamic assembly of IgG oligomers upon antigen recognition. ACS Nano 14:2739–2750. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b08347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Heesterbeek DA, Bardoel BW, Parsons ES, Bennett I, Ruyken M, Doorduijn DJ, Gorham RD, Berends ET, Pyne AL, Hoogenboom BW, Rooijakkers SH. 2019. Bacterial killing by complement requires membrane attack complex formation via surface‐bound C5 convertases. EMBO J 38:e99852. doi: 10.15252/embj.201899852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kumar S, Cartron ML, Mullin N, Qian P, Leggett GJ, Hunter CN, Hobbs JK. 2017. Direct imaging of protein organization in an intact bacterial organelle using high-resolution atomic force microscopy. ACS Nano 11:126–133. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b05647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yamashita H, Taoka A, Uchihashi T, Asano T, Ando T, Fukumori Y. 2012. Single-molecule imaging on living bacterial cell surface by high-speed AFM. J Mol Biol 422:300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nievergelt AP, Banterle N, Andany SH, Gönczy P, Fantner GE. 2018. High-speed photothermal off-resonance atomic force microscopy reveals assembly routes of centriolar scaffold protein SAS-6. Nat Nanotechnol 13:696–701. doi: 10.1038/s41565-018-0149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nievergelt AP, Brillard C, Eskandarian HA, McKinney JD, Fantner GE. 2018. Photothermal off-resonance tapping for rapid and gentle atomic force imaging of live cells. Int J Mol Sci 19:2984. doi: 10.3390/ijms19102984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dufrêne YF, Martínez-Martín D, Medalsy I, Alsteens D, Müller DJ. 2013. Multiparametric imaging of biological systems by force-distance curve-based AFM. Nat Methods 10:847–854. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Alsteens D, Pesavento E, Cheuvart G, Dupres V, Trabelsi H, Soumillion P, Dufrêne YF. 2009. Controlled manipulation of bacteriophages using single-virus force spectroscopy. ACS Nano 3:3063–3068. doi: 10.1021/nn900778t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Roos WH, Gertsman I, May ER, Brooks CL, Johnson JE, Wuite G. 2012. Mechanics of bacteriophage maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:2342–2347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109590109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pfreundschuh M, Harder D, Ucurum Z, Fotiadis D, Müller DJ. 2017. Detecting ligand-binding events and free energy landscape while imaging membrane receptors at subnanometer resolution. Nano Lett 17:3261–3269. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b00941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jiang Z, Zhang S, Klausen LH, Song J, Li Q, Wang Z, Stokke BT, Huang Y, Besenbacher F, Nielsen LP, Dong M. 2018. In vitro single-cell dissection revealing the interior structure of cable bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:8517–8522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1807562115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pillet F, Formosa-Dague C, Baaziz H, Dague E, Rols M-P. 2016. Cell wall as a target for bacteria inactivation by pulsed electric fields. Sci Rep 6:19778. doi: 10.1038/srep19778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Alsteens D, Trabelsi H, Soumillion P, Dufrêne YF. 2013. Multiparametric atomic force microscopy imaging of single bacteriophages extruding from living bacteria. Nat Commun 4:2926. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Formosa C, Schiavone M, Boisrame A, Richard ML, Duval RE, Dague E. 2015. Multiparametric imaging of adhesive nanodomains at the surface of Candida albicans by atomic force microscopy. Nanomedicine (Lond) 11:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Viljoen A, Viela F, Kremer L, Dufrêne YF. Fast chemical force microscopy demonstrates that glycopeptidolipids define nanodomains of varying hydrophobicity on mycobacteria. Nanoscale Horiz, in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Formosa-Dague C, Fu Z-H, Feuillie C, Derclaye S, Foster TJ, Geoghegan JA, Dufrêne YF. 2016. Forces between Staphylococcus aureus and human skin. Nanoscale Horiz 1:298–303. doi: 10.1039/C6NH00057F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Delguste M, Peerboom N, Le Brun G, Trybala E, Olofsson S, Bergström T, Alsteens D, Bally M. 2019. Regulatory mechanisms of the mucin-like region on herpes simplex virus during cellular attachment. ACS Chem Biol 14:534–542. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.9b00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Delguste M, Zeippen C, Machiels B, Mast J, Gillet L, Alsteens D. 2018. Multivalent binding of herpesvirus to living cells is tightly regulated during infection. Sci Adv 4:eaat1273. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Beaussart A, El-Kirat-Chatel S, Sullan RMA, Alsteens D, Herman P, Derclaye S, Dufrêne YF. 2014. Quantifying the forces guiding microbial cell adhesion using single-cell force spectroscopy. Nat Protoc 9:1049–1055. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Alsteens D, Newton R, Schubert R, Martinez-Martin D, Delguste M, Roska B, Müller DJ. 2017. Nanomechanical mapping of first binding steps of a virus to animal cells. Nat Nanotechnol 12:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2016.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]