Abstract

The goal of the study was to examine the association between statin use and the development of acute diverticulitis requiring hospital admission.

Acute diverticulitis is a common and costly gastrointestinal disorder. Although the incidence is increasing its pathophysiology and modifiable risk factors are incompletely understood. Statins affect the inflammatory response and represent a potential risk reducing agent.

A retrospective, population-based, case-control study was carried out on a cohort of adults, resident in Canterbury, New Zealand. All identified cases were admitted to hospital and had computed tomography confirmed diverticulitis. The positive control group comprised patients on non-aspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and the negative control group were patients on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Medicine exposure was obtained from the Pharmaceutical Management Agency of New Zealand. Subgroup analysis was done by age and for complicated and recurrent diverticulitis.

During the study period, there were 381,792 adults resident in Canterbury. The annual incidence of diverticulitis requiring hospital presentation was 18.6 per 100,000 per year. Complicated disease was seen in 37.4% (158) of patients, and 14.7% (62) had recurrent disease. Statins were not found to affect the risk of developing acute diverticulitis, nor the risk of complicated or recurrent diverticulitis. Subgroup analysis suggested statin use was associated with a decreased risk of acute diverticulitis in the elderly (age >64 years). NSAIDs were associated with a decreased risk of acute diverticulitis (risk ratio = 0.65, confidence interval: 0.26–0.46, P < .01), as were SSRIs (risk ratio = 0.37, confidence interval: 0.26–0.54, P < .01).

This population-based study does not support the hypothesis that statins have a preventative effect on the development of diverticulitis, including complicated disease. We also found a decreased risk of diverticulitis associated with NSAID and SSRI use.

Keywords: diverticulitis, nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, statins

1. Introduction

Diverticulitis is a common, costly, and usually acutely presenting gastrointestinal disorder, with approximately 20% of people requiring surgery on their first presentation.[1,2,3,4] Although the incidence of diverticulitis is increasing, particularly among younger age groups,[5,6,7] its pathophysiology and modifiable risk factors are incompletely understood, and are of increasing research interest.

The classical pathogenesis of diverticulitis was traditionally considered a process initiated by obstruction and trauma to a diverticulum, with subsequent ischemia and bacterial overgrowth. This theory has been challenged with new research indicating a multifactorial pathway involving genetic and environmental predisposition, alteration in the colonic microbiome, and chronic inflammation through dysregulated immune response.[8,9,10]

Statins have been shown to affect the inflammatory response. Statins decrease T-cell activation by inhibiting antigen presentation, reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha), and increasing the production of anti-inflammatory molecules (interleukin-10).[11,12,13] Statins may also affect intestinal permeability, impacting leucocyte migration and bacterial translocation, and promote the growth of anti-inflammatory luminal bacteria.[14,15] As such, they may have a role in modifying an episode of acute diverticulitis. Further evidence on the possible effects of statins on acute diverticulitis would be of benefit in helping both to understand the pathophysiology, and to quantify the potential for risk reduction of acute diverticulitis.

The aim of this study is to examine the association between statin use and the development of acute diverticulitis requiring hospital admission, including complicated and recurrent disease.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This was a retrospective, population-based, case-control study. The source population was a cohort of adults, resident in Canterbury, New Zealand between January 1, 2003 and January 31, 2008, identified from the National Census.

2.2. Case identification

Cases of diverticulitis were identified from a prospectively maintained database containing all adult patients aged 20 years or over assessed at the Christchurch Hospital, with computed tomography (CT)-proven acute diverticulitis between July 2003 and December 2008. CT was readily available during this period, and routinely carried out in the work-up of patients with suspected diverticulitis. Christchurch Hospital is the only provider of acute general surgical services within Canterbury, including both public and private sectors. Therefore, all patients within the Canterbury population, with diverticulitis severe enough to warrant hospital presentation, were captured.

2.3. Control identification

Positive and negative controls were used. The positive control group comprised patients on non-aspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), as previous studies have reported this as a risk factor for acute diverticulitis, and there is a high prevalence of NSAID use in the population.[16,17,18,19,20,21]

The negative control group were patients on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), as SSRIs have not been shown to influence the rate or severity of diverticulitis, and it is a class of medicine commonly used in the general population.

2.4. Drug exposure

Data on drug exposures were obtained from the Pharmaceutical Management Agency of New Zealand, which is a national body that funds prescribed medicines in New Zealand. A database containing information on all of the prescriptions filled in the Canterbury region, between January 2003 and December 2008, was searched to identify all prescriptions of statins, SSRIs, and NSAIDS by adults during that period.

For patients in the diverticulitis database, “statin users” were defined as those who had a prescription filled for atorvastatin, simvastatin or pravastatin within the 6 months before the CT diagnosis date. NSAID and SSRI users were defined in the same manner.

2.5. Case definitions

Uncomplicated diverticulitis was defined as the presence of colonic diverticulae with localized wall thickening and/or stranding of pericolic fat on CT scan. Complicated diverticulitis was defined as the presence of abscess, perforation (including any pericolic or extraluminal gas), obstruction, fistula formation, or an associated mass lesion, consistent with published literature.[22,23,24] Recurrent disease was defined as a second CT-proven episode occurring at least 3 months after the initial presentation. In this study, adults were defined as aged 20 years or over, and elderly patients were those aged 65 years or over. These groupings were chosen to allow comparison with population data from the New Zealand census report.

2.6. Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the rate of CT-proven diverticulitis. Secondary outcome measures were the rates of complicated disease and recurrent diverticulitis.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp, New York, NY, 2015). Two subgroups were analyzed: patients aged 65 or over, and those aged 20 to 64 years. Pearson Chi-squared test was used for categorical variables. Risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for the risk of diverticulitis, and for the subgroups of complicated and recurrent disease, for each medicine. Significance was set at P < .05.

2.8. Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained for this study from the Upper South B Regional Ethics Committee of New Zealand (reference 15/STH/160).

3. Results

During the study period, there were 381,792 adults resident in Canterbury, of which 309,180 were aged 20 to 64 years and 72,612 were 65 years or older.

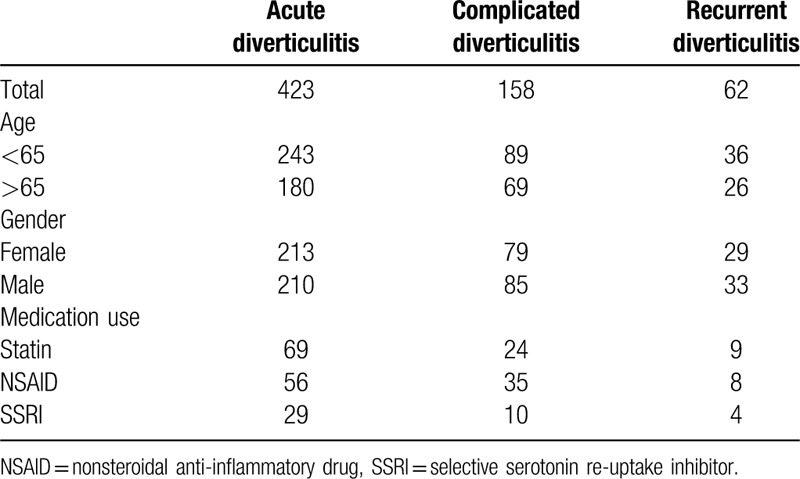

Demographic, diverticular disease, and medicine use data are shown in Table 1. There were 423 patients with diverticulitis, of which 243 (57%) were under 65 years of age, and 180 (43%) were 65 years or older.

Table 1.

Demographic, pathology, and medicine use.

The annual incidence of diverticulitis requiring hospital presentation was 18.6 per 100,000 per year. When subdivided by age, the annual incidence was 13.1 and 41.3 per 100,000 per year in the under 65 years and 65 years and older subgroups, respectively.

Of those diagnosed with diverticulitis, 158 (37.4%) were complicated, and 62 (14.7%) had recurrent disease. There were 69 statin users, 56 NSAID users, and 29 SSRI users. There was no missing data.

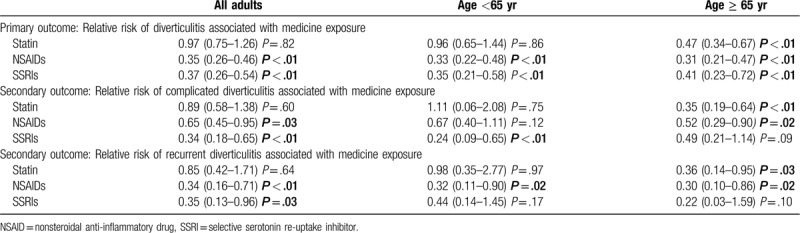

The relative risks for diverticulitis associated with each medicine are shown in Table 2 and are further stratified by age. Statins were not found to affect the risk of developing diverticulitis, nor the risk of complicated or recurrent diverticulitis. In subgroup analysis, there was a decreased risk of acute diverticulitis in the 65 years and older age group (RR = 0.47, CI: 0.34–0.67, P < .01), including for complicated (RR = 0.35, CI: 0.19–0.64, P < .01) and recurrent disease (RR = 0.36 CI: 0.14–0.95, P = .03).

Table 2.

Relative risk for diverticulitis, including complicated and recurrent, associated with medicine use.

NSAIDs were associated with a decreased risk of acute diverticulitis (RR = 0.65, CI: 0.26–0.46, P < .01), complicated diverticulitis (RR = 0.65, CI: 0.45–0.95, P = .03) and recurrent diverticulitis (RR = 0.34, CI: 0.16–0.71, P < .01).

SSRIs were also associated with a decreased risk of acute diverticulitis (RR = 0.37, CI: 0.26–0.54, P < .01), complicated diverticulitis (RR = 0.34, CI: 0.18–0.65, P < .01) and recurrent diverticulitis (RR = 0.35, CI: 0.13–0.96, P = .03).

4. Discussion

Diverticulitis is a common and costly health problem that is increasing in incidence. If an effective prophylactic treatment could be identified, this would represent disease altering progress. This study did not show any association between statin use and the risk of developing acute diverticulitis, including complicated or recurrent disease. We found 2 unexpected results with the decreased risk of acute diverticulitis in those exposed to NSAIDs and SSRIs.

There is no proven effective prophylactic medical treatment for acute diverticulitis, though studies have examined the roles of a wide array of medications including rifaximin, mesalazine, calcium channel blockers (CCB), metformin, statins, and more recently probiotics.

The prevention of diverticulitis with rifaximin was investigated in a meta-analysis comprising data from 4 studies that included 1660 patients with symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease, and concluded that rifaximin improves self-reported symptoms, but does not prevent diverticulitis.[25] This meta-analysis was limited by the scientific quality of the included studies, for example, only 1 study was placebo-controlled.

Mesalamine has predominantly been studied in the prevention of recurrent diverticulitis. A meta-analysis including 1423 patients in 4 placebo-controlled randomized controlled trials found no evidence to support a role for mesalamine in the prevention of recurrent diverticulitis, and 2 subsequently published randomized controlled trials found the same results.[26,27]

CCB and metformin were both associated with decreased risk of diverticulitis in small retrospective studies; CCB were examined in a case-control study of 120 patients with perforated diverticulitis, and metformin in a cohort of 175 diabetic patients with acute diverticulitis. Both studies were at risk of bias and confounding and further studies are needed to further clarify these associations.[28,29]

Recently several small studies have examined the role of probiotics in the prevention of diverticulitis. One study with 15 participants investigated symptoms and recurrence rates associated with treatment with Escherichia coli Nissle, following uncomplicated diverticulitis. Patients treated with E coli Nissle had a longer recurrence-free interval by 2.4 months. The effect of Lactobacillus casei in addition to a therapy with mesalazine was investigated in 90 patients with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. The authors concluded that both substances may have some effect on symptom relief and prevent recurrence. However, the small number of patients studied, the lack of placebo control, and the short follow-up time limited the conclusions that could be drawn from this study.

Two observational studies have previously looked at the use of statins and risk of diverticulitis. A study from the UK General Practice Database by Humes et al reported an odds ratio of 0.44 (95% CI 0.20–0.95) for diverticular perforation in regular statin users.[30] A Swedish population-based study by Sköldberg et al found an odds ratio for current statin use of 0.70 (95% CI 0.55–0.89) for acute diverticulitis requiring surgical treatment. However, neither study found any effect on the risk of uncomplicated diverticulitis.[31]

The main finding of our study is in agreement with Sköldberg et al suggesting no associated between statin use and risk of acute diverticulitis. However, in contrast to the findings of Sköldberg et al and Humes et al, that identified a decreased risk for complicated disease in those taking statins, we found no association between statin use and complicated diverticulitis. This may be due to the differing definitions of complicated disease used in the studies – in our study, complicated disease was diagnosed on CT as any abscess, perforation, obstruction, fistula formation, or associated mass lesion. Some of these cases would have been managed conservatively without surgery, and; therefore, would not be captured in the definition of complicated disease defined in the study by Sköldberg et al. This may account for the lower rates of complicated diverticulitis reported in that study compared to our study (7% vs 37%). Humes et al reported only on those patients with perforated diverticulitis, and excluded other forms of complicated disease. Statin use of 16.3% in the present study is similar to the rate reported in the study by Sköldberg et al (14.9%) but considerably higher than that in the study by Humes et al (0.78%), likely reflecting increasing population statin use in the last 20 years.[32,33,34]

Statin use in individuals over 65 was associated with decreased risk of diverticulitis in the present study. The reasons for this are unclear. Statin use increases with age, and the proportion of patients prescribed statins for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in this age group is higher.[35] Risk factors for cardiovascular disease overlap with risk factors for acute diverticulitis; smoking, low levels of physical activity, and obesity.[36,37,38,39,40] These risk factors will differ in prevalence among a population using statins for primary verses secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and are; therefore, potential confounders when comparing statin use in young and older populations. There is also higher prevalence of comorbidity and polypharmacy among elderly. Furthermore, with subgroup analysis, the absolute numbers are smaller and; therefore, the chance of type 1 error occurring are higher.

An unexpected finding from our study was a decreased risk of acute diverticulitis associated with prescription NSAID use. Numerous observational studies have reported on the risk of diverticulitis with NSAID exposure. Most report an increased risk,[19,20] particularly in relation to complicated disease,[16,17,18,21] while 1 large study reported no association.[30] The present study is susceptible to bias from ascertainment of NSAID medication exposure – in addition to prescribed usage, NSAIDs are available “over the counter” in New Zealand and this is not captured in the Pharmaceutical Management Agency of New Zealand data used in our study, which implies an underestimation of NSAID use in our cohort. Furthermore, patients with mild diverticulitis may be prescribed NSAIDs by their general practitioner with or without oral antibiotics, resolving their symptoms and avoiding the need for hospital presentation, and thereby avoiding capture in our database.

Our finding of a decreased risk of diverticulitis associated with SSRI exposure was also unexpected. This observation has not been previously been reported and may be an area for future research. The gut-brain axis is an emerging area of research, and several groups have reported the interaction of SSRIs with the gut microbiome.[41,42]As the microbiome has also been postulated to be involved in diverticulitis,[43,44,45] medications that interfere with gut-brain signaling may also have an effect on gut diseases, such as diverticulitis.

Recurrent diverticulitis is likely to become an increasing problem, with increasing overall incidence of diverticulitis, and particularly among younger individuals. In our study the absolute numbers of recurrent diverticulitis in each medication group were small, leading to wide CIs, and hence we were not able to draw any conclusions about the effect of these medications on recurrent disease.

The strengths of the study are the population-based design and the complete coverage of prescription data, reducing the risk of recall bias. Our prospective database and the use of CT to confirm and stage disease minimizes the risk of misdiagnosis or under-staging of disease severity. The main limitation of this study, and other observational studies, is that medicines are prescribed because of disease and this introduces unmeasured confounders that could not been accounted for, which may have influenced our results. Other limitations of this study include the assumption of a fixed population and the exclusion of diverticulitis managed in the community.

5. Conclusions

This population-based study does not support the hypothesis that statins have a preventative effect on the development of diverticulitis, including complicated disease. We found a decreased risk of acute diverticulitis among elderly and that NSAID and SSRI use is associated with a lower risk of diverticulitis in our population.

Author contributions

The authors co-ordinated the project and contributed to writing of the manuscript. MD and JP provided clinical pharmacology and statistical oversight and input respectively.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CCB = calcium channel blocker, CI = confidence interval, CT = computed tomography, NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, RR = risk ratio, SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

How to cite this article: O’Grady M, Clarke L, Turner G, Doogue M, Purcell R, Pearson J, Frizelle F. Statin use and risk of acute diverticulitis: a population-based case-control study. Medicine. 2020;99:20(e20264).

Michael O’Grady is a recipient of a Canterbury Medical Research Foundation Scholarship.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from a third party, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the third party.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Regenbogen SE, Hardiman KM, Hendren S, et al. Surgery for diverticulitis in the 21st century. JAMA Surg 2014;149:292–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Eglinton T, Nguyen T, Raniga S, et al. Patterns of recurrence in patients with acute diverticulitis. Brit J Surg 2010;97:952–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Janes S, Meagher A, Frizelle FA. Elective surgery after acute diverticulitis. Brit J Surg 2005;92:133–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1500–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Broad JB, Wu Z, Xie S, et al. Diverticular disease epidemiology: acute hospitalisations are growing fastest in young men. Tech Coloproctol 2019;23:713–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Teetor T, Palachick B, Grim R, et al. The changing epidemiology of diverticulitis in the United States. Am Surg 2017;83:e134–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bharucha AE, Parthasarathy G, Ditah I, et al. Temporal trends in the incidence and natural history of diverticulitis: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterology 2015;110:1589–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Strate LL, Morris AM. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of diverticulitis. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1282–98.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Schieffer KM, Kline BP, Yochum GS, et al. Pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Expert Rev Gastroent 2018;12:683–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Morris AM, Regenbogen SE, Hardiman KM, et al. Sigmoid diverticulitis: a systematic review. JAMA 2014;311:287–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Youssef S, Stüve O, Patarroyo JC, et al. The HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, atorvastatin, promotes a Th2 bias and reverses paralysis in central nervous system autoimmune disease. Nature 2002;420:78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Peery AF, Crockett SD, Barritt AS, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1731–41.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kwak B, Mulhaupt F, Myit S, et al. Statins as a newly recognized type of immunomodulator. Nat Med 2000;6:1399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bereswill S, Muñoz M, Fischer A, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of resveratrol, curcumin and simvastatin in acute small intestinal inflammation. Plos One 2010;5:e15099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sasaki M, Bharwani S, Jordan P, et al. The 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitor pravastatin reduces disease activity and inflammation in dextran-sulfate induced colitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2003;305:78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Morris CR, Harvey IM, Stebbings WSL, et al. Anti-inflammatory drugs, analgesics and the risk of perforated colonic diverticular disease. Brit J Surg 2003;90:1267–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Campbell K, Steele RJC. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and complicated diverticular disease: a case—control study. Brit J Surg 1991;78:190–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Piekarek K, Israelsson LA. Perforated colonic diverticular disease: the importance of NSAIDs, opioids, corticosteroids, and calcium channel blockers. Int J Colorectal Dis 2008;23:1193–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Reichert MC, Krawczyk M, Appenrodt B, et al. Selective association of nonaspirin NSAIDs with risk of diverticulitis. Int J Colorectal Dis 2018;33:423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Strate LL, Liu YL, Huang ES, et al. Use of aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increases risk for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. Gastroenterology 2011;140:1427–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wilson RG, Smith AN, Macintyre IMC. Complications of diverticular disease and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a prospective study. Brit J Surg 1990;77:1103–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Strate LL, Peery AF, Neumann I. American gastroenterological association institute technical review on the management of acute diverticulitis. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1950–76.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. Commissioning Guide for Colonic diverticular disease. 2014. Available at: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/files/rcs/library-and-publications/non-journal-publications/colinic-diverticular-disease-commissioning-guide.pdf Accessed 8 April 2020

- [24].Feingold D, Steele SR, Lee S, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum 2014;57:284–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bianchi M, Festa V, Moretti A, et al. Meta-analysis: long-term therapy with rifaximin in the management of uncomplicated diverticular disease. Aliment Pharm Therap 2011;33:902–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Khan MA, Ali B, Lee WM, et al. Mesalamine does not help prevent recurrent acute colonic diverticulitis: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterology 2016;111:579–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kruis W, Kardalinos V, Eisenbach T, et al. Randomised clinical trial: mesalazine versus placebo in the prevention of diverticulitis recurrence. Aliment Pharm Therap 2017;46:282–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Freckelton J, Evans JA, Croagh D, et al. Metformin use in diabetics with diverticular disease is associated with reduced incidence of diverticulitis. Scand J Gastroentero 2017;52:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Morris CR, Harvey IM, Stebbings WSL, et al. Do calcium channel blockers and antimuscarinics protect against perforated colonic diverticular disease? A case control study. Gut 2003;52:1734–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Humes DJ, Fleming KM, Spiller RC, et al. Concurrent drug use and the risk of perforated colonic diverticular disease: a population-based case–control study. Gut 2011;60:219–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sköldberg F, Svensson T, Olén O, et al. A population-based case–control study on statin exposure and risk of acute diverticular disease. Scand J Gastroentero 2015;51:203–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Salami JA, Warraich H, Valero-Elizondo J, et al. National trends in statin use and expenditures in the US adult population from 2002 to 2013: insights from the medical expenditure panel survey. JAMA Cardiol 2016;2:56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Laleman N, Henrard S, van den Akker M, et al. Time trends in statin use and incidence of recurrent cardiovascular events in secondary prevention between 1999 and 2013: a registry-based study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2018;18:209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Mortensen MB, Falk E, Schmidt M. Twenty-year nationwide trends in statin utilization and expenditure in Denmark. Circulation Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2017;10:e003811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kildemoes HW, Vass M, Hendriksen C, et al. Statin utilization according to indication and age: a Danish cohort study on changing prescribing and purchasing behaviour. Health Policy 2012;108:216–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Liu P-H, Cao Y, Keeley BR, et al. Adherence to a healthy lifestyle is associated with a lower risk of diverticulitis among men. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:1868–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Strate LL. Lifestyle factors and the course of diverticular disease. Dig Dis Basel Switz 2012;30:35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Turner GA, O’Grady M, Frizelle FA, et al. Influence of obesity on the risk of recurrent acute diverticulitis. Anz J Surg 2020;Mar 4. doi: 10.1111/ans.15784. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Wijarnpreecha K, Boonpheng B, Thongprayoon C, et al. Smoking and risk of colonic diverticulosis: a meta-analysis. J Postgrad Med 2018;64:35–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Aune D, Sen A, Leitzmann MF, et al. Body mass index and physical activity and the risk of diverticular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Nutr 2017;56:2423–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lukić I, Getselter D, Ziv O, et al. Antidepressants affect gut microbiota and Ruminococcus flavefaciens is able to abolish their effects on depressive-like behavior. Transl Psychiat 2019;9:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lyte M, Daniels KM, Schmitz-Esser S. Fluoxetine-induced alteration of murine gut microbial community structure: evidence for a microbial endocrinology-based mechanism of action responsible for fluoxetine-induced side effects. Peerj 2019;7:e6199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Schieffer KM, Sabey K, Wright JR, et al. The microbial ecosystem distinguishes chronically diseased tissue from adjacent tissue in the sigmoid colon of chronic, recurrent diverticulitis patients. Sci Rep-UK 2017;7:8467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Gueimonde M, Ouwehand A, Huhtinen H, et al. Qualitative and quantitative analyses of the bifidobacterial microbiota in the colonic mucosa of patients with colorectal cancer, diverticulitis and inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:3985–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Daniels L, Budding AE, Korte N, et al. Fecal microbiome analysis as a diagnostic test for diverticulitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol 2014;33:1927–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]