Abstract

Cervical mucus produced by the endocervix plays an essential role as a hormonally induced regulator of female fertility. Cervical mucus fluctuates in both physical characteristics and in sperm penetrability in response to estrogens and progestogens. However, the mechanisms by which steroid hormones change mucus remains poorly understood. Current in vitro models have limited capability to study these questions as primary endocervical cells possess limited expansion potential, and immortalized cells lose in vivo characteristics such as steroid sensitivity. Here we overcome these limitations by establishing an in vitro primary endocervical cell culture model using conditionally reprogrammed cells (CRCs). CRC culture utilizes a Rho-kinase inhibitor and a fibroblast feeder layer to expand proliferative potential of epithelial cell types that have normally short in vitro life spans. In our studies, we produce CRC cultures using primary endocervical cells from adult female rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). We demonstrate that primary endocervical cells from the nonhuman primate can be robustly expanded using a CRC method, while retaining steroid receptor expression. Moreover, when removed from CRC conditions and switched to differentiation conditions, these cells are able to differentiate and produce mucus including MUC5B, the most prevalent mucin of the endocervix. We conclude that this method provides a promising in vitro platform for conducting mechanistic studies of cervical mucus regulation as well as for screening new therapeutic targets for fertility regulation and diseases of the endocervix.

Keywords: cervix, contraception, fertility, steroid hormones/steroid receptors, reprogramming, primates, progesterone receptor, hormone receptors, female reproductive tract

Conditionally reprogrammed macaque endocervical cells retain steroid receptor expression and produce mucus.

Introduction

The endocervix plays an essential regulatory role in female fertility and serves as a natural barrier to the upper female genital tract. Columnar epithelial cells lining the endocervix produce mucus in response to the hormonal fluctuations of the menstrual cycle. Peri-ovulation, thin, fluid mucus serves to facilitate sperm entry into the upper tract for fertilization. Meanwhile in the early follicular and luteal phases, when conception is not possible, highly viscous and scant mucus presents as a barrier to both sperm and ascending pathogens [1].

The signaling mechanisms through which hormonal factors induce changes leading to favorable and unfavorable mucus remains poorly understood [2]. While we know that estrogens and progestogens regulate many factors that influence the qualities of mucus, such as mucin protein production or the luminal ion milieu, we do not fully understand the detailed signaling pathways through which progestogens act through, nor do we know the mediators of mucus hydration that change most critically in response to hormonal signaling. Identification of these pathways would also help us to understand how infectious disease transmission may be modified by hormonal contraceptives [3].

Defining these signaling pathways is difficult using existing approaches. Clinical appraisal methods such as the commonly used mucus score (Insler) only grossly evaluate the physical characteristics of mucus with undefined biological significance [2]. Other methods such as sperm penetration are plagued by lack of methodological standardization [2, 4]. Moreover, the normal endogenous hormone fluctuations during natural cycles and person to person variability make the design and interpretation of results from human experiments difficult.

Cell cultures provide an inexpensive model system to study complex pathways, but only if the cells retain the same characteristics as the native tissue during the experiment. Prior studies have shown that primary cultures of endocervical epithelial cells have poor longevity, while immortalized or tumor based cell lines often lose characteristics of expression of hormonal receptors over time or lack characterization of mucus production [5–7]. Thus, we do not have an established in vitro platform for performing detailed mechanism studies of endocervical mucus production.

Conditionally reprogrammed cells (CRCs) provide a culturing method for propagating primary epithelial cells that allow growth and expansion without the use of viral transduction [8,9]. Epithelial cells, directly isolated from tissues are co-cultured with mitotically inactivated Swiss mouse 3 T3 fibroblast feeder cells (J2s) and a Rho protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor (Y-27632). Previous studies suggest that these conditions induce a stem-cell like state in differentiated cells that can be reversed upon removal from these conditions. Conditional reprogramming has been used to culture a number of different human and animal tissues including lung, breast, and prostate [8–12].

An endocervical cell culture system that reliably models signaling pathways critical for mucus production would provide a useful platform for mechanistic experiments examining novel pathways in fertility, contraception, and infectious diseases. We sought to determine if application of the CRC method for the propagation of non-human primate endocervical could generate a model system to study mucus production in vitro. We compared the growth and expansion potential of primary epithelial endocervical cells grown under standard and CRC conditions. We then evaluated whether the cell cultures became hormonal responsive when moved to differentiation conditions, and whether they produced mucus including MUC5B, the primary mucin of the endocervix [13,14]. Finally, we evaluated if they retained hormonally responsive to estradiol and progesterone.

Methods

Harvesting of tissue

The Oregon National Primate Research Center (ONPRC), Division of Comparative Medicine provided animal care and husbandry for the macaques in this study. The ONPRC Animal Care and Use Committee reviewed and approved all animal procedures. We carried out all work in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health.

We obtained tissue and mucus from reproductive-aged female rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) undergoing necropsy at the ONPRC for unrelated reasons. To recover mucus, we bi-valved the cervix, washed the luminal surface of the endocervix with 200 μL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and then aspirated the luminal washings with a 1 mL slip tip insulin syringe. We fixed a portion of the cervical tissue in 4% formaldehyde solution for immunohistochemistry (IHC). To separate endocervical cells from the underlying stromal tissue, we used a scalpel and then minced and washed the sample with 70% ethanol. Prior to culture, the samples were further prepared by digestion with 5 mL of dispase (5 U/mL STEMCELL Technologies), 1 mL collagenase/hyaluronidase (10X, STEMCELL Technologies), and 7 mL of culturing F medium (see description below) for 2 h in a 37 °C rocking incubator, followed by passage through a 40-μm cell strainer (Corning). Alternatively, if tissues were not cultured immediately, they were cryopreserved after being minced [DMEM (90%, Fisher), DMSO (5%, Sigma Aldrich), FBS (5%, ATCC), 30 mM HEPES in Ham’s F12 (Fisher)] in liquid nitrogen. The frozen tissue could later be thawed at 37 °C and resuspended in digestion medium.

Cell culture conditions

CRC conditions

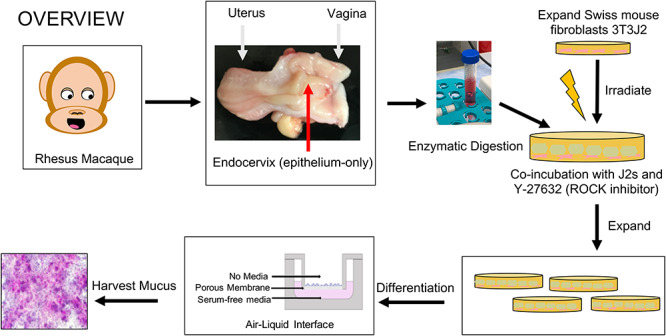

We followed methods derived by Liu et al. [8] to culture conditionally reprogrammed endocervical cells. Figure 1 presents an overview of the methodology. Swiss 3 T3 J2 mouse fibroblast feeder cells (Kerafast) were grown in standard culture flasks in complete DMEM [(500 mL) of DMEM with L-glutamine (Fisher), FBS (10%, ATCC), penicillin/streptomycin (1 x 104 units/mL, Fisher)]. We then used a cesium irradiator (3000 rads) to render the feeder cells mitotically inactive. For the initial seeding, we first plated 1 x 104 irradiated J2s on a T-25 cell culture flask (Fisher) coated with rat-tail collagen I (5 μg/cm2, Gibco) and allowed these to establish for 2–24 h. We then added ~1.5 x 105 digested primary cells in reprogramming or “F” medium [373 mL complete DMEM (same as above), insulin (5 μg/mL, Sigma Aldrich), amphotericin B (250 ng/mL, Fisher), gentamicin (10 μg/mL, Gibco), cholera toxin (0.1 nM, Sigma Aldrich), epidermal growth factor (0.125 ng/mL, Life Technology), hydrocortisone (25 ng/mL, Sigma Aldrich), and ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (10 μM, Enzo)] [8]. We changed the medium every 2–3 days. CRC cultures using primary endocervical cells (CRECs) were passaged when they reached ~80% confluence and moved to a collagen coated 10-cm culture dish pre-plated with 2.5–3 x 105 J2s, 2–24 h in advance. Cells were passaged with Trypsin-EDTA (0.05% Gibco) in two successive washes, first to remove the fibroblasts (~1 min), and then repeated to remove epithelial cells (~5 min). Subsequent passages were done at ~ 80% confluence usually every 2–7 days and passaged at a 1:10 dilution.

Figure 1.

Overview of method for generating primary endocervical cultures from rhesus macaques using conditional reprogramming (CR): We adapted this protocol from Liu et al [8]. We obtained the cervix from female rhesus macaques undergoing necropsy at the ONPRC. The fresh cervix was bi-valved and the epithelial layer of the endocervix was separated and either banked in a frozen repository or enzyme digested for immediate culture. Digested tissue is placed in CR conditions by co-culturing with irradiated mouse fibroblast feeder cell and a Rho-kinase (ROCK) inhibitor. Cells are expanded and passaged in this fashion until they reach adequate numbers. For differentiation, cells are plated onto permeable membrane supports and cultured in a high calcium, serum-free medium in the basal compartment only (ALI). By 7 days, they produce mucus that can be washed and collected (mucus visualized here with periodic acid-Schiff).

Non CRC conditions

We compared expansion potential of primary cells in CRC conditions to two additional cell culturing conditions. Cells collected from a single endocervix were harvested, digested, and prepped in the usual fashion and freshly plated in equal aliquots to CRC conditions (F medium with pre-plated J2s), “serum-rich” conditions (F medium without Y-27632 or J2s) and a commercial, supplemented “serum-free” medium designed for cervical cells (ReproLife CX, Lifeline Cell Technology). Again, we passaged cells once they reached 80% confluency. Once cells reached 80% confluence on a 10-cm plate (~1 x 106 cells), they were moved to differentiation conditions (see below).

Endocervical differentiation and mucus collection

In order to differentiate CRECs to produce mucus, we transferred aliquots containing ~1 x 105 cells to 12-mm polycarbonate permeable supports [Transwell (0.4 μm pore size), Corning] initially in F medium [8]. Once the cells reached 100% confluence in F medium (~24 h), we switched to our serum-free differentiation medium (ReproLife CX, Lifeline Cell Technology) and added calcium chloride (total concentration = 0.4 mM, Sigma Aldrich) and converted the permeable support to an air–liquid interface (ALI) by removal of the apical medium. These conditions allow endocervical cultures to polarize and produce tight junctions [6,15,16]. We maintained cells at these conditions with regular medium changes every 2–3 days. To collect mucus secretions, we added 200 μL of PBS (Gibco) to the apical layer for 20 min and incubated at 37 °C prior to removal of the fluid/mucus mixture with a pipette (mucus washings). We began mucus collections at 7 days and repeated every 2–3 days until we sacrificed the culture at the experimental endpoints.

Hormonal evaluations

For conditions evaluating estradiol effects alone, we added 17β estradiol (10−8 M, Sigma Aldrich) to our differentiation medium every other day for 7 days. For progesterone studies, we initially primed cells with 17β estradiol (10−8 M) for 7 days followed by progesterone (10−7 M, Sigma Aldrich) and estradiol (10−9 M) for 48 h [6,17].

Trans epithelial electrical resistance measurements of differentiated cells

In order to evaluate for cellular polarization, formation of a monolayer and confirmation of barrier integrity, we measured the trans epithelial electrical resistance (TEER) of our differentiated cells over time. About 200 μL of culture medium was added to the apical side of the permeable support and voltage resistance between apical and basolateral chambers was measured with a volt-ohm meter (EVOM2, World Precision Instruments) using a Chopstick Electrode (STX3) (World Precision Instruments). We took measurements every 48 h. We calculated sample resistance by subtracting the resistance of a blank insert in medium measured at the same time. After measurement, apical medium was discarded to return the culture to an ALI.

Cell counts

We predetermined six random locations on the culture dish and captured images in those fields using an Insight Gigabit camera (Spot Imaging) on an AX10 microscope (Zeiss) at 50x every other day. The photographs were threshold processed with ImageJ (Version 1.51, NIH) in order to create cleaned, binary images of the cells. We then analyzed the images for cell count and compared to hand count of images in each batch for verification.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR assays

We extracted RNA from our cell cultures using TRIzol RNA+ (Invitrogen) mini-kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was quantified using the Nanodrop system (ThermoFisher). We used the Superscript III First Strand cDNA Synthesis (Invitrogen) to generate cDNA from 1 μg of RNA.

We assessed our undifferentiated CRECs cells as well as the differentiated endocervical cultures in separate hormone conditions (E2-only, E2 + P4, Vehicle) for expression of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor (PGR), and MUC5B. We used feeder cells alone as negative controls for hormone receptor expression. RNA extracted from Rhesus endocervical cells (uncultured) were used as positive controls. Quantitative PCR was performed on an ABI Prism 7900HT (Applied Biosystems) to evaluate relative gene expression to 18S ribosomal RNA. We used Taqman gene expression assays for ESR1 (Hs011046816_m1) and PGR (Rh01556702). For MUC5B, we used a custom Taqman primer/probe set (ThermoFisher) verified by DNA sequencing of the PCR product: Parent sequence (NM_002458) sense 5′-GAGTGGTTTGATGAGGACTACC-3′, anti-sense 5′-CTTAGGCTGCTGGCATAAGT-3′, probe 5′-CTTAGGCTGCTGGCATAAGT-3′.

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry

Pre-differentiated cells were grown on glass cover slips, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Sigma Aldrich) at room temperature or 100% ice cold methanol (Sigma Aldrich) for 20 min, washed, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 (Sigma Aldrich) before undergoing antibody staining using standard protocols. Transwell cultures with TEERS > 500 ohms were fixed using 4% PFA, processed in successive ethanol baths, embedded in paraffin, cut in 5 μm sections and mounted on glass slides. For IHC, M. mulatta endocervical cross-sections were fixed in 4% PFA, processed, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned using standard protocols.

For immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical studies, we incubated with the following primary antibodies and stains overnight at 4 °C: steroid receptor studies [estrogen receptor (1:250), ab-11 (ThermoFisher Scientific)]; mucus studies [MUC5B (1:2000), UNC414 (gift from Camille Ehre at UNC), wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) lectin (1:1000) (Sigma Aldrich), periodic acid Schiff (PAS) (Abcam)]; and phenotype makers [secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI, 1:250), HPA027774 (Sigma), Cytokeratin 18 (1:500), ab7797 (abcam)]. Immunofluorescence slides were subsequently incubated with florescent 2° antibodies (Abcam), DAPI (Sigma Aldrich) and mounted with Prolong Gold antifade reagent (Fisher). Tissues sections after incubation with primary antibodies were stained with EnVision+ Dual Link Kit (Agilent) or Vectatain Elite ABC Universal Plus Kit (Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturers protocol.

All immunofluorescence pictures were captured by sequential imaging, whereby the channel track was switched each frame to avoid cross-contamination between channels, using a Leica SP5 AOBS spectral inverted laser-scanning confocal system in the Imaging and Morphology Core at ONPRC. Images were obtained in multiple focal planes and combined using Fiji to create a single image that captured the complexity of thicker ALI cultures. For IHC, we captured images using an inverted light microscope (Zeiss AX10) captured using an Insight Gigabit camera (Spot Imaging). For each stained image visualized by microscopy, we assessed three different areas of the Transwell membrane in more than three separate experiments. Representative images are displayed.

Protein staining

We concentrated diluted M. mulatta cervical mucus samples and ALI washings three-fold by vacuum centrifugation and separated bands using a Mini-Protean TGX 4–20% Precast gel (Bio Rad) in a Mini-Protean electrophoresis apparatus (Bio Rad). The gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 staining solution (Bio Rad) and photographed with a FluorChem M system (Protein Simple). The bands were analyzed for migration distance and intensity using ImageJ.

Dot blot

Transwell washings (100 μL) and M. mulatta cervical mucus samples were loaded onto a 0.45-μm nitrocellulose blotting membrane (Life Sciences) using an S&S Minifold I dot blot apparatus (Life Sciences), incubated with the UNC414 anti-MUC5B antibody, photographed with a FluorChem M system (Protein Simple), and analyzed with ImageJ.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses for qPCR were performed with Qbase+ analysis software version 3.2 (Biogazelle) using non-parametric two-way analysis of variance for differences between using the Mann–Whitney test. Values of P value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Conditionally reprogrammed cells allow for rapid expansion of endocervical cells

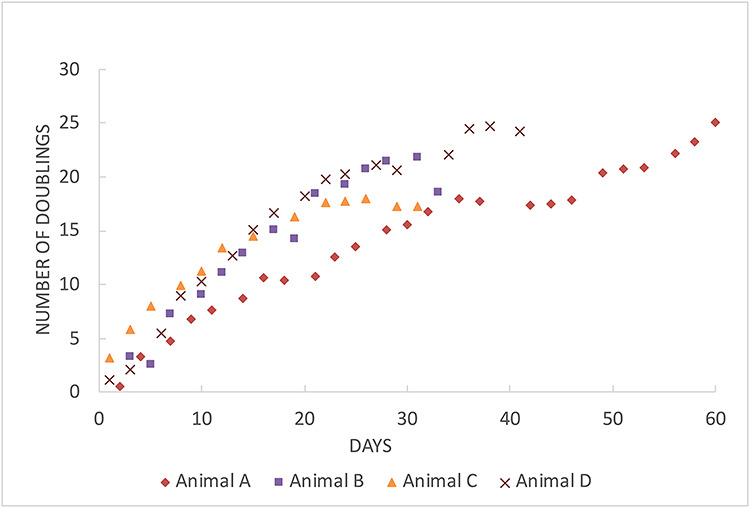

We generated primary cell cultures from 17 rhesus macaque specimens with 14 cultures successfully producing passageable epithelial cultures. We did not have enough samples from the luteal phase to determine if timing of collection during the menstrual cycle influenced outcomes (Supplementary Table 1). We found that CRC conditions induced rapid cellular expansion. While on day 1, there were no visible epithelial colonies, by day 4 we counted anywhere from 25 000 to half a million cells and by 1 week we had over a million cells in most cultures (Figure 2). Cells grown on collagen coated plastic surfaces grew in epithelial “cobblestone” like colonies of heterogenous appearance consistent with population reprogramming rather than clonal selection [9] (Figure 3A and B). Seeded cells typically reached 70% confluence by 1 week, at which point we observed exponential growth with preservation of cellular and morphological appearance. Between the second and seventh sub-culturing, we had an average doubling time of 1.23 days. We performed cell counts and noted the number of doublings observed for several cultures. We observed morphological changes consistent with senescence (enlarged, fried egg appearance) for some cultures around 30 doublings from our first count and confirmed this with B-galactosidase. Cryopreserved tissue could be thawed and cultured reliably, and cultured cells could be robustly re-cultured after cryopreservation (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Population doubling curves of four representative CREC cultures: cultures show linear rates of growth through ~20 doublings, and then decline.

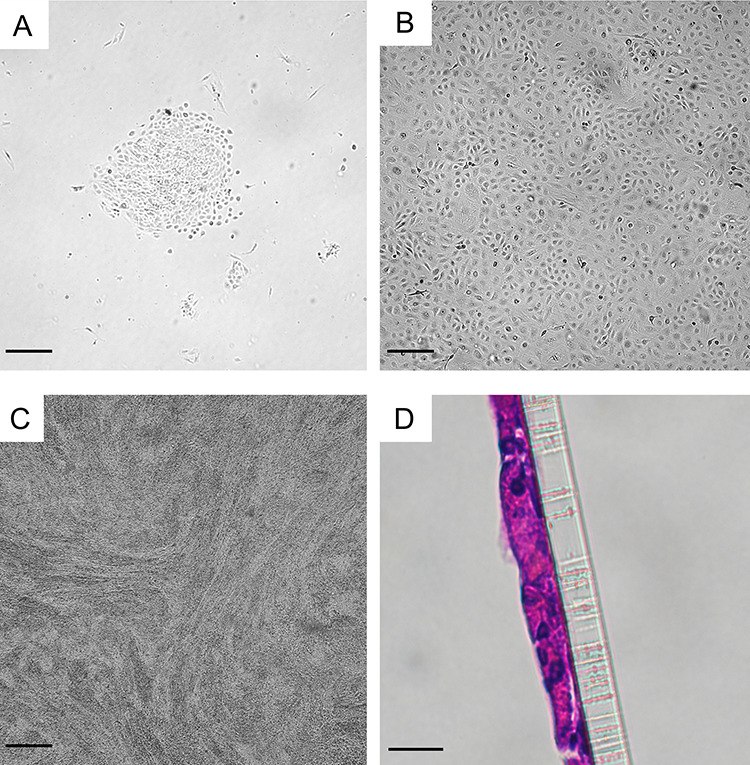

Figure 3.

Appearance and identification of CREC cultures: (A) Microscopic images of endocervical microscopic images of primary endocervical cells culturing in conditional reprogramming conditions ~48 h after seeding and again (B) prior to passaging at 7 days. (C) CRECs differentiated in ALI conditions with high calcium (0.4 mM) and serum-free conditions. Bars A–C = 100 μm. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of CRECs on a Transwell membrane 7 days after differentiation. Bar D = 10 μm.

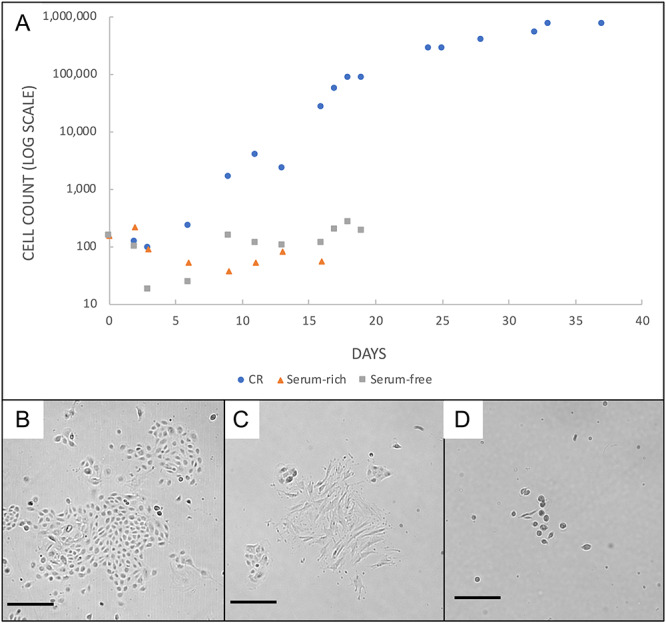

Figure 4.

Comparison of primary endocervical cultures in three different growth conditions: (A) Primary endocervical cells in conditional reprogramming grew faster and longer than cells cultured in serum rich (w/o ROCK inhibitor and feeder cells) or serum-free media. Morphological appearance of primary endocervical cells at 5 days in conditional reprogramming media (B), serum-free media (C), and serum-rich media (D). All Bars = 100 μm.

In contrast, cells cultured under non-CRC conditions grew slower and could not be sub-cultured (Figure 4A). We did not count more than ~ 50 000 and ~ 250 000 cells in serum-rich and serum-free conditions, respectively. In the case of serum-free cultures, cells demonstrated a different morphology and all cultures appeared senescent by ~2 weeks. With serum-rich conditions, cells became either senescent or infiltrated with fibroblast cells by also 2 weeks. By comparison, CRECs cultured from the same seeding material reached one million cells at ~1 week, could be moved to differentiation conditions at that time and maintained their growth over at least 6 weeks. Representative images are shown in Figure 4B–D. These results were consistent over three different experiments from three different animals.

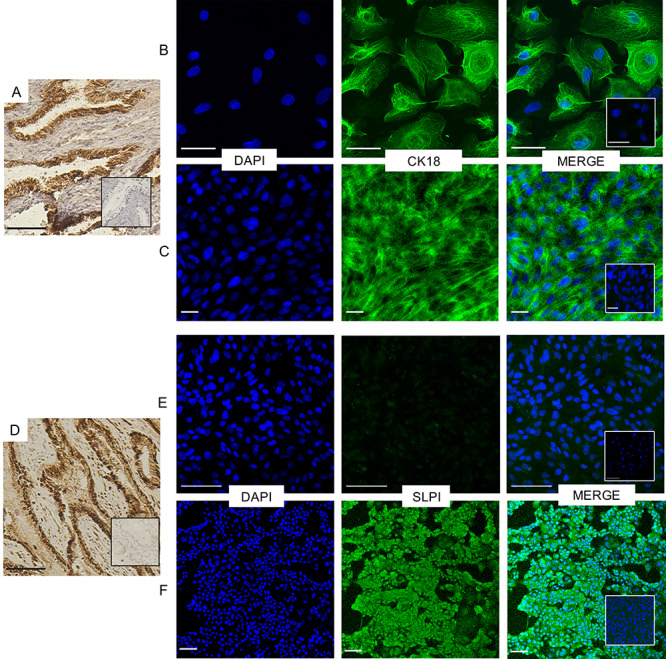

Figure 5.

Immunostaining of CRECs for endocervical cell markers: (A) Histologic section of rhesus macaque endocervix showing positive expression of cytokeratin 18 (CK18), Bar = 90 μm. Both pre- (B) and post- (C) differentiated CRECS show cytoskeletal expression after incubation with anti-CK18 and a 488 secondary antibody, Bars = 50 μm. (D) Histologic section of rhesus macaque endocervix showing positive expression of SLPI, Bar = 90 μm. (E) Undifferentiated endocervical cells incubated with anti-SLPI rabbit antibody do not express SLPI, (Bar = 100 μm) but (F) differentiated cells show SLPI cellular localization in the cytosol as well as in the secreted mucus, Bar = 50 μm.

CRECs express endocervical cell markers and polarize once differentiated.

After we converted our cultures to differentiation conditions, we used antibody stains to confirm an endocervical phenotype for our cells. Epithelial cells in the reproductive tract demonstrate selective expression of cytoskeletal proteins in vivo. Cytokeratin 18 (CK18) is absent in the stratified squamous non-keratinizing ectocervix, but present in the endocervical epithelia [5,18,19]. Immunofluorescence demonstrated strong CK18 staining in CRECs both pre and post differentiation (Figure 5B and C) in a cytoskeletal pattern consistent with that seen in our IHC staining of the endocervix (Figure 5A). SLPI is a secreted elastase inhibitor highly specific to glandular epithelium, including cells of the endocervix (Figure 5D), but absent in ectocervix, endometrial glands or vagina [20–22]. While pre-differentiated CRECs did not stain positively for SLPI, differentiated CRECs did express SLPI by immunofluorescence, again consistent with IHC expression of SLPI in our endocervical tissues (Figure 5E and F).

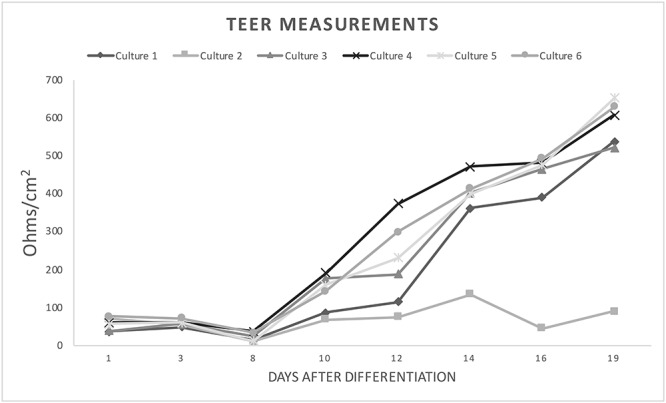

Figure 6.

TEER of differentiated CRECs: TEER measurements made with a chopstick electrode on a volt-ohm meter increase over time after differentiation in permeable supports. Sample resistance was calculated by subtracting the resistance of a blank insert. Sample resistance for all but one culture reached resistance measurements > 500 ohms by 19 days. These findings are consistent with appearance of water-tight apical membranes.

We also assessed differentiated cultures for tight junction integrity every 2 days. Cultures showed a successive increase in TEER measurements over time (Figure 6), and reached >300 Ω/cm2 of resistance by 2 weeks and >500 Ω/cm before 3 weeks. Under microscopy, these cultures maintained dry apical membranes consistent with tight junction and morphological appearance consistent with differentiation (Figure 3C and D).

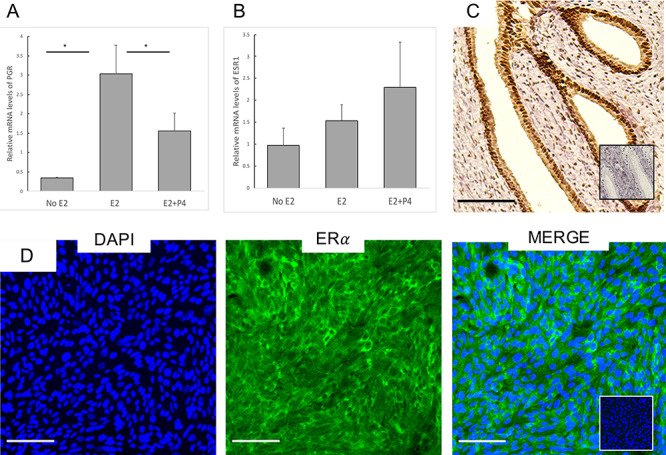

Figure 7.

Hormone receptor expression and sensitivity: Differentiated CRECs were primed with 7 days of E2 (10 nm) followed by 48 h of E2 + P4 medium (1 nM, 100 nm). Expression levels were normalized to 18S and hormone containing conditions were compared to no hormone conditions for (A) PGR and (B) estrogen receptor α (ESR1). PGR levels were significantly higher in E2 conditions compared to no E2 and E2 + P4 conditions. (C) Histologic section of rhesus macaque endocervix stained for ERα. (D) Differentiated CRECs also demonstrate ERα. All Bars = 100 μm.

Differentiated CRECs are hormonally responsive

We compared ERα (ESR1) and PGR receptor transcript expression of differentiated CRECs in hormone-free conditions to E2 and E2 + P4 conditions. Compared to hormone-free conditions, we found that the addition of E2 to our CRECs significantly upregulated PGR. We also found PGR was significantly downregulated by E2 + P4 conditions compared to E2 only conditions (Figure 7A). In contrast, ESR1 was present, but not significantly downregulated by E2 + P4 conditions (Figure 7B). Similar hormonal regulation of PGR has been reported from cervical biopsy specimens samples obtained from many species, including primates [23–25]. Of note, our differentiated CRECs retained these sex-steroid responses even after 15 doublings. We used immunofluorescent staining of our differentiated cell cultures to confirm presence of ER in CRECs incubated with E2 (Figure 7C and D).

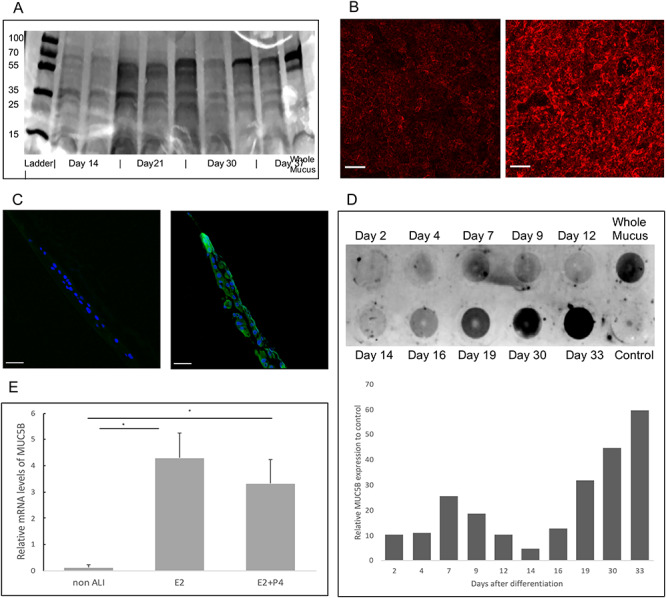

Figure 8.

Mucus assessment of cultures washing. (A) Aliquots of apical washings from cultures were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 4–20% gradient gel and visualized with Coomassie blue staining. Protein bands at 70, 60, 38 and 25 and 15 are visible in all washings as well as in whole mucus. (B) CRECs stained with fluorescent WGA-lectin (red). WGA-lectin binds to the N-acetylglucosaminyl present in secreted mucins and is seen much greater at ALI day 7 (right) compared to day 0 (left). (C) Sections of Transwells showing immunofluorescence of MUC5B (green) and DAPI (blue) of cultures at ALI day 0 (left) and ALI day 7 (right) demonstrating presence of secreted MUC5B after 1 week in differentiation conditions. (Bars = 10 μm) (D) Dot blot probed with MUC5B antibody of apical washings (200 μL) with increased collection of MUC5B over time. (E) MUC5B mRNA expression (ALI day 7) in E2 vs E2 + P4 conditions compared to cells before differentiation (non-ALI) demonstrates expression of MUC5B is induced by differentiation conditions.

Differentiated CRECCs secrete mucins including MUC5B

To demonstrate that differentiated CRECs produce secretions similar to the whole cervix, we first compared washings obtained from our differentiated cultures to macaque mucus specimens using gel electrophoresis and protein staining. We found similar band patterns between our in vitro collected secretions and in vivo mucus, and that these patterns persisted throughout our collection time periods (Figure 8A). We then sought to identify mucus-like proteins in our washings by staining for lectins as in-direct evidence of mucin production. Lectins are glycan specific carbohydrate binding proteins and not mucin specific. However, previous work supports their use as a biomarker of mucus changes and WGA-lectin appears to preferentially distribute in the same pattern as MUC5B [26,27]. Differentiated cells stained positive for WGA lectin antibody (Figure 8B). Using a MUC5B specific antibody, we performed immunofluorescence on ALI day 0 and ALI day 7 and found that differentiation of CRECs leads to expression of MUC5B (Figure 8C). Using dot blots, we semi-quantitatively assessed the amount of MUC5B obtained over the course of 6 weeks and found increasing amounts of MUC5B in the washings over time (Figure 8D). Using qPCR, we also demonstrate that differentiation of CREC cells leads to significant upregulation of MUC5B transcript compared to pre-differentiation conditions (Figure 8E).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that conditional reprogramming enables rapid propagation of primary endocervical cells in culture, and that following differentiation conditions these cells demonstrate functional estrogen receptor and PGR, and markers of an endocervical phenotype. We also provide the first known experiments characterizing and comparing mucin and mucus secretion derived from an endocervical cell culture with endocervical mucus samples obtained from living animals. Lung research has long established the use of permeable supports to culture glandular epithelium for the measurement of mucin secretions in response to environmental challenges [12,28]. However, previous studies of endocervical cells have not evaluated the secreted mucus itself [6,7]. Using an antibody specific to MUC5B [15], the most prevalent mucin in endocervical mucus, we demonstrated that mucin secretion is robust in this culture system and induced by differentiation conditions. In contrast, endocervical cells cultured in non-CRC conditions did not undergo expansion or differentiation.

Like previous work in other tissues using conditional reprogramming, we found growth conditions with a Rho-kinase inhibitor and fibroblast feeder layer led to rapid and robust expansion of primary endocervical cells [12,29]. Currently, there is not a well-established in vitro model for studying epithelial cell function in the cervix as primary endocervical cells demonstrate limited expansion potential when cultured. Permeability and electrophysiological studies of ion transport require the establishment of a large number of cells on permeable membrane supports (105 cells/12 mm Transwell) to achieve electrostatically tight conditions, and adequate replicates. While these growth conditions can be achieved with immortalized or cancer-lines, these modifications typically lead to loss of in vivo properties such as steroid receptor expression reducing the utility of the model [6,30] [6].

Previous experiments with primary endocervical cells cultured using traditional in vitro methods have not resulted in models that produce mucus and remain hormonally responsive. Turyk et al. [31] achieved a mean of 15 doublings before senescence with almost 20 days of culturing before the first subculture. Similarly, Deng et al. [5] tested five different mediums and report achieving up to 20 population doublings before senescence. However, it appears that neither investigator achieved robust cellular proliferation, as they counted less than 3 x 104 and 3 x 103 cells, respectively, at 1 week. We compared the technique of CRC to primary endocervical cell culture in our lab, using serum-free, keratinocyte medias similar to those used by Turyk and Deng and were unable to produce enough cells to successfully passage them to permeable supports. Meanwhile serum-free media is often preferred because serum-rich medium leads to overgrowth with fibroblasts, a result we confirmed in 2/3 of our attempts to grow primary endocervical cell cultures in serum-rich conditions [8]. One additional study from Arslan et al. [7] demonstrated that endocervical cells could be grown in a 3D polystyrene scaffold, but did not describe the longevity of the culture, or whether the cells would differentiate to produce harvestable mucus in a polarizing environment. In contrast, CRC conditions allowed us to sub-culture our cells in only 7 days (with most cultures containing over one million cells by this point) and we obtained over 30 doublings in some cases, without fibroblast overgrowth.

Our results differed from previous reports of conditionally reprogrammed cultures of mammary, prostate, and lungs cells in that we did not find our cells to be indefinitely expandable in CRC conditions [8]. While previous experiments found proliferation at the same rate >100 days and >100 doublings, we saw the rate of cell growth slow after 25–30 doublings (30–60 days). The reduced capacity for conditional reprogramming may be related to the underlying difficulty in culturing primary endocervical cells. Another possibility is that endocervical epithelial cells require paracrine signals or growth factors derived from neighboring cell types such as endocervical stromal cells. The absence of these local regulating factors present in whole tissues represents an important limitation of this method. With any in vitro model, experimental finding eventually need to be corroborated with whole tissue or whole animal studies.

Another advantage of CRC derived primary cell culture lines is that they result from population reprogramming rather than clonal selection [9,29]. Differentiated CRC derived cells maintain their phenotype and do not overexpress transcription factors seen in induced pluripotent stem cells and embryonic stem cells (ESC) [9]. Researchers interested in disease variation find this particularly attractive because CRC-derived primary cell culture lines maintain genetic similarity to their parent tissue even after 30+ doublings [29]. These findings suggest that in-vitro experiments with CRCs, in particular therapeutic experiments, could capture the variance in population response and potentially be used as a platform for advancing personalized medicine.

A better understanding of the precise hormonal regulation of mucus would have high value in contraception and fertility research. The majority of women in the United States using reversible contraception rely on short acting, hormonally based methods [32]. For all hormonal methods, but especially low dose progestin-only contraceptive methods (e.g. norethindrone progestin-only pill; LNG-IUS) that do not reliably block ovulation, the progestin-induced thickening of cervical mucus (hostile to sperm penetration) serves as a critical mechanism of action. While the physiological effects of progestogens on cervical mucus are well documented, we do not know if thickening of mucus results from a direct inhibitory effect of the ligand acting through PGR, or indirectly through downregulation of estrogen receptor-mediated effects. Our findings that the addition of P4 to the cell culture downregulates PR in the presence of E2 are consistent with results seen in the endometrium and as well as whole animal experiments in the macaque and mouse [23,25,33]. However, direct effects of progesterone found elsewhere [34] remain unexplored in the regulation of cervical mucus and delineating these mechanisms could potentially yield new nonhormonal targets for contraceptive drug development. The clinical significance cannot be understated as for many women, the perceived risks of hormonal therapy outweigh perceived benefits, and this contributes to nonuse and unintended pregnancy [35–37].

While conditional reprogramming offers advantages to other endocervical culture techniques, additional unanswered questions remain for future studies. Since our CREC do not demonstrate the same potential for expansion as seen in lung, prostate, or mammary epithelial cells, research is needed to determine if later passages of CRECs have the same genetic and phenotypical profiles as earlier [8,9]. While this question deserves further study, it does not limit the utility of the model to evaluate physiology at earlier passages. Additionally, while our cultures demonstrate functional steroid receptors, we need to determine if hormonal responsiveness recapitulates in vivo changes.

In summary, our studies demonstrate that conditional reprogramming of primary endocervical cells establishes a robust, in vitro, primary endocervical cell culture system that, upon differentiation, maintains steroid hormones, and produces cervical mucus. This model provides a potential platform not only for mechanistic experiments to understand mucus regulation, but also a possible screening platform for drugs, toxins, and pathogens that affect the endocervix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Camille Ehre for providing MUC5B (UNC 414) and expertise in mucin assessment.

Funding

This research received support from the grant K12 HD000849, awarded to the Reproductive Scientist Development Program by the NICHD. In addition this work received funding from The March of Dimes Foundation, American Society for Reproductive Medicine and American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology as part of the RSDP, Medical Foundation of Oregon and ONPRC core grant number P51 OD011092.

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

- 1. Moghissi KS, Syner FN, Evans TN. A composite picture of the menstrual cycle. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1972; 114:405–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Han L, Taub R, Jensen JT. Cervical mucus and contraception: What we know and what we don’t. Contraception 2017; 96:310–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Govender Y, Avenant C, Verhoog NJD, Ray RM, Grantham NJ, Africander D, Hapgood JP. The injectable-only contraceptive medroxyprogesterone acetate, unlike norethisterone acetate and progesterone, regulates inflammatory genes in endocervical cells via the glucocorticoid receptor. Plos One 2014; 9:e96497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grimes DA. Validity of the postcoital test. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995; 172:1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deng H, Mondal S, Sur S, Woodworth CD. Establishment and optimization of epithelial cell cultures from human ectocervix, transformation zone, and endocervix optimization of epithelial cell cultures. J Cell Physiol 234:7683–7694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buckner LR, Schust DJ, Ding J, Nagamatsu T, Beatty W, Chang TL, Greene SJ, Lewis ME, Ruiz B, Holman SL, Spagnuolo RA, Pyles RB et al. Innate immune mediator profiles and their regulation in a novel polarized immortalized epithelial cell model derived from human endocervix. J Reprod Immunol 2011; 92:8–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arslan SY, Yu Y, Burdette JE, Pavone ME, Hope TJ, Woodruff TK, Kim JJ. Novel three dimensional human endocervix cultures respond to 28-day hormone treatment. Endocrinology 2015; 156:1602–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu X, Krawczyk E, Suprynowicz FA, Palechor-Ceron N, Yuan H, Dakic A, Simic V, Zheng Y-L, Sripadhan P, Chen C, Lu J, Hou T-W et al. Conditional reprogramming and long-term expansion of normal and tumor cells from human biospecimens. Nature Protocols 2017; 12:439–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Suprynowicz FA, Upadhyay G, Krawczyk E, Kramer SC, Hebert JD, Liu X, Yuan H, Cheluvaraju C, Clapp PW, Boucher RC, Kamonjoh CM, Randell SH et al. Conditionally reprogrammed cells represent a stem-like state of adult epithelial cells. PNAS 2012; 109:20035–20040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alamri AM, Kang K, Groeneveld S, Wang W, Zhong X, Kallakury B, Hennighausen L, Liu X, Furth PA. Primary cancer cell culture: mammary-optimized versus conditional-reprogramming. Endocr Relat Cancer 2016; 23:535–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jin L, Qu Y, Gomez LJ, Chung S, Han B, Gao B, Yue Y, Gong Y, Liu X, Amersi F, Dang C, Giuliano AE et al. Characterization of primary human mammary epithelial cells isolated and propagated by conditional reprogrammed cell culture. Oncotarget 2018; 9:11503–11514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gentzsch M, Boyles SE, Cheluvaraju C, Chaudhry IG, Quinney NL, Cho C, Dang H, Liu X, Schlegel R, Randell SH. Pharmacological rescue of conditionally reprogrammed cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2016; 56:568–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Andersch-Björkman Y, Thomsson KA, Larsson JMH, Ekerhovd E, Hansson GC. Large scale identification of proteins, mucins, and their O-glycosylation in the endocervical mucus during the menstrual cycle. Mol Cell Proteomics 2007; 6:708–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gipson IK, Spurr-Michaud S, Moccia R, Zhan Q, Toribara N, Ho SB, Gargiulo AR, Hill JA. MUC4 and MUC5B transcripts are the prevalent mucin messenger ribonucleic acids of the human Endocervix. Biol Reprod 1999; 60:58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhu Y, Maric J, Nilsson M, Brännström M, Janson P-O, Sundfeldt K. Formation and barrier function of tight junctions in human ovarian surface epithelium. Biol Reprod 2004; 71:53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martin WR, Brown C, Zhang YJ, Wu R. Growth and differentiation of primary tracheal epithelial cells in culture: regulation by extracellular calcium. J Cell Physiol 1991; 147:138–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hombach-Klonisch S, Kehlen A, Fowler PA, Huppertz B, Jugert JF, Bischoff G, Schlüter E, Buchmann J, Klonisch T. Regulation of functional steroid receptors and ligand-induced responses in telomerase-immortalized human endometrial epithelial cells. J Mol Endocrinol 2005; 34:517–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moll R, Levy R, Czernobilsky B, Hohlweg-Majert P, Dallenbach-Hellweg G, Franke WW. Cytokeratins of normal epithelia and some neoplasms of the female genital tract. Lab Invest 1983; 49:599–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gorodeski GI, Eckert RL, Utian WH, Rorke EA. Maintenance of in vivo-like keratin expression, sex steroid responsiveness, and estrogen receptor expression in cultured human ectocervical epithelial cells. Endocrinology 1990; 126:399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Casslén B, Rosengren M, Ohlsson K. Localization and quantitation of a low molecular weight proteinase inhibitor, antileukoprotease, in the human uterus. Hoppe-Seyler’s Z Physiol Chem 1981; 362:953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moriyama A, Shimoya K, Ogata I, Kimura T, Nakamura T, Wada H, Ohashi K, Azuma C, Saji F, Murata Y. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) concentrations in cervical mucus of women with normal menstrual cycle. Mol Hum Reprod 1999; 5:656–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Franken C, Meijer CJ, Dijkman JH. Tissue distribution of antileukoprotease and lysozyme in humans. J Histochem Cytochem 1989; 37:493–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mehta FF, Son J, Hewitt SC, Jang E, Lydon JP, Korach KS, Chung S-H. Distinct functions and regulation of epithelial progesterone receptor in the mouse cervix, vagina, and uterus. Oncotarget 2016; 7:17455–17467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Al-Hendy A, Wang HQ, Copland JA. Expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors in the human endocervix. Middle East Fertil Soc J 2018; 11:216–221. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Slayden O, Bond Kise, Wilcox Corinne. Hormonal regulation of cervix transcript expression in the menstrual cycle. The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus (Slayden) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE110476 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE110476. Accessed 1 May 2018.

- 26. Ostedgaard LS, Moninger TO, McMenimen JD, Sawin NM, Parker CP, Thornell IM, Powers LS, Gansemer ND, Bouzek DC, Cook DP, Meyerholz DK, Abou Alaiwa MH et al. Gel-forming mucins form distinct morphologic structures in airways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017; 114:6842–6847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reynoso-Prieto M, Takeda M, Prakobphol A, Seidman D, Averbach S, Fisher S, Smith-McCune K. Menstrual cycle-dependent alterations in glycosylation: a roadmap for defining biomarkers of favorable and unfavorable mucus. J Assist Reprod Genet 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hill DB, Button B. Establishment of respiratory air–liquid interface cultures and their use in studying mucin production, secretion, and function. Mucins 2012; 842:245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mahajan AS, Sugita BM, Duttargi AN, Saenz F, Krawczyk E, McCutcheon JN, Fonseca AS, Kallakury B, Pohlmann P, Gusev Y, Cavalli LR. Genomic comparison of early-passage conditionally reprogrammed breast cancer cells to their corresponding primary tumors. Plos One 2017; 12:e0186190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Herbst-Kralovetz MM, Quayle AJ, Ficarra M, Greene S, Rose WA, Chesson R, Spagnuolo RA, Pyles RB. Quantification and comparison of toll-like receptor expression and responsiveness in primary and immortalized human female lower genital tract epithelia. Am J Reprod Immunol 2008; 59:212–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Turyk ME, Golub TR, Wood NB, Hawkins JL, Wilbanks GD. Growth and characterization of epithelial cells from normal human uterine ectocervix and endocervix. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol 1989; 25:544–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Guttmacher Institute Contraceptive Use in the United States. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Slayden OD, Brenner RM. Hormonal regulation and localization of estrogen, progestin and androgen receptors in the endometrium of nonhuman primates: effects of progesterone receptor antagonists. Arch Histol Cytol 2004; 67:393–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cahill MA. Progesterone receptor membrane component 1: an integrative review. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2007; 105:16–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peipert JF, Gutmann J. Oral contraceptive risk assessment: a survey of 247 educated women. Obstet Gynecol 1993; 82:112–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rosenberg MJ, Waugh MS, Meehan TE. Use and misuse of oral contraceptives: risk indicators for poor pill taking and discontinuation. Contraception 1995; 51:283–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Emans S, Grace E, Woods ER, Smith DE, Klein K, Merola J. Adolescents’ compliance with the use of oral contraceptives. JAMA 1987; 257:3377–3381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.