Abstract

The movement of cruise ships has the potential to be a major trigger of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreaks. In Australia, the cruise ship Ruby Princess became the largest COVID-19 epicenter. When the Ruby Princess arrived at the Port of Sydney in New South Wales on March 19, 2020, approximately 2700 passengers disembarked. By March 24, about 130 had tested positive for COVID-19, and by March 27, the number had increased to 162. The purpose of this study is to analyze the relationship between the cruise industry and the COVID-19 outbreak. We take two perspectives: the first analysis focuses on the relationship between the estimated number of cruise passengers landing and the number of COVID-19 cases. We tracked the movement of all ocean cruise ships around the world using automatic identification system data from January to March 2020. We found that countries with arrival and departure ports and with ports that continued to accept cruise ships until March have a higher COVID-19 infection rate than countries that did not. The second analysis focuses on the characteristics of cruise ships infected with COVID-19. For this purpose, we utilize the list named “Cruise ships affected by COVID-19” released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As a result, cruise ships infected with COVID-19 were large in size and operated regular cruises that sailed from the same port of arrival and departure to the same ports of call on a weekly basis.

Keywords: Cruise industry, Cruise ship movement, COVID-19, Coronavirus, Automatic Identification System, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Highlights

-

•

Tracking cruise ships around the world using AIS data from January to March 2020.

-

•

Comparison of estimated cruise passengers landing and COVID-19 cases by country

-

•

COVID-19 infection rates are high in countries with ports of arrival and departure.

-

•

COVID-19 infection rates are high in countries that accept cruise ships until March 2020.

-

•

Cruise ships infected with COVID-19 have large size, fixed itinerary, weekly operation.

1. Introduction

Cruise ship movements can be a major trigger of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreaks. In Australia, the cruise ship Ruby Princess became the largest COVID-19 epicenter. When the Ruby Princess arrived at the Port of Sydney on March 19, 2020, approximately 2700 passengers disembarked. On arrival, 130 passengers and crew members with flu-like symptoms were tested for the new virus. However, the officials of New South Wales allowed the other passengers to disembark before the test results were available. The next day, four people tested positive. Infection continued however, among the passengers who had disembarked, and the number rose to 162 by March 27 (Reuters, 2020).

Signs that cruise ships may become a source of infection had already appeared in early February. The largest cluster of COVID-19 cases outside mainland China occurred on board the Diamond Princess, which was quarantined in the port of Yokohama, Japan on February 3 (WHO, 2020). On March 6, cases of COVID-19 were identified on the Grand Princess off the coast of California; the ship was subsequently quarantined. By March 17, confirmed cases of COVID-19 had been associated with at least 25 additional cruise ships (CDC, 2020a).

The purpose of this study is to analyze the relationship between the cruise industry and the COVID-19 outbreak. We attempt the analysis from two perspectives. The first analysis focuses on the relationship between the estimated number of cruise passengers landing and the number of COVID-19 cases. The second analysis focuses on the characteristics of cruise ships infected with COVID-19. For the first analysis, we use automatic identification system (AIS) data to track the global movement of ocean cruise ships and estimate the number of cruise passengers landing in each country. In the second analysis, we compare ship sizes and itinerary characteristics from the CDC's list of cruise ships infected with COVID-19.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the analysis of cruise ship movement using AIS data. Section 3 shows the relationship between the estimated number of cruise passengers landing and COVID-19 outbreaks by country. In Section 4, we show the relationship between the on board characteristics of infected cruise ships and the COVID-19 outbreak and present a judgement for the moment, because the COVID-19 infection is continuously expanding. We conclude in Section 5.

2. Method description

In the first analysis in Section 3, we use AIS data to track the global movement of ocean cruise ships in service from January to March. We identify all ocean cruise ships registered as “Passenger/Cruise” on the ship registration database, Maritime IHS (2020). A total of 392 ocean cruise ships were in operation. The movement data are based on the date and time when the cruise ship enters the port. After obtaining movement data of the cruise ships at each port, we divide the data into ten cruise areas (Appendix 1). In the second analysis in Section 4, we compare ship sizes and itinerary characteristics from the CDC's list of cruise ships infected with COVID-19 using ship data. With this, we analyze the characteristics of cruise ships infected with COVID-19.

3. Cruise passengers landing and the COVID-19 outbreak

3.1. Tracking cruise ship movements from January to March

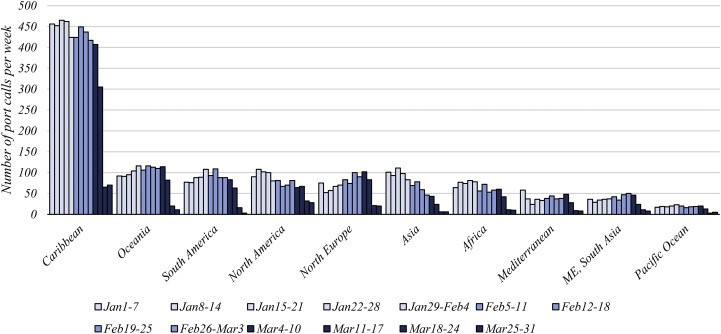

Fig. 1 shows the total number of calls per week for each cruise area. The Caribbean has the largest number, followed by Oceania, South America, and North America. In terms of the number of port calls, the Caribbean is 400 to 450 times a week from January to February, 300 times in the second week of March, and approximately 50 times from the third week in March.

Fig. 1.

Number of port calls per week by cruise area.

Source: Authors based on the AIS data.

3.2. Estimating cruise passengers landing by country

In order to observe the relationship between the number of cruise passengers landing and COVID-19 transmission, the former is calculated using Eq. (1).

| (1) |

Li represents the number of passengers landing in country i. P i is a port in country i. R is all services for cruise products. N r is the number of port calls for service r. C r is the capacity of service r. x p,r is 1 if service r calls at port p, and 0 otherwise. The number of cruise passengers landing by country from January to March and the number of COVID-19 cases by country until April 15 are calculated as shown in Table 1 . This study uses the capacity of cruise ships instead of actual passengers of cruise ships due to data unavailability. The US had the largest number of cruise passengers (4.71 million), followed by Mexico (2.06 million), Bahamas (1.90 million).

Table 1.

Estimated number of cruise passengers landing and COVID-19 Cases by country.

| Countries and territories | Passengers landinga | COVID casesb | Countries and territories | Passengers landinga | COVID casesb | Countries and territories | Passengers landinga | COVID casesb | Countries and territories | Passengers landinga | COVID Casesb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States of America | 4,709,671 | 609,516 | 36 | China | 192,293 | 83,352 | 71 | Mauritius | 37,022 | 324 | 106 | Senegal | 2485 | 299 |

| 2 | Mexico | 2,066,815 | 5399 | 37 | Madeira | 181,981 | N/A | 72 | Greece | 36,794 | 2170 | 107 | Ireland | 2426 | 11,479 |

| 3 | Bahamas | 1,898,830 | 49 | 38 | Colombia | 181,875 | 2979 | 73 | Cambodia | 35,527 | 122 | 108 | Ukraine | 2310 | 3372 |

| 4 | Australia | 990,197 | 6416 | 39 | Norway | 181,156 | 6566 | 74 | French Polynesia | 34,680 | 55 | 109 | Kenya | 1844 | 216 |

| 5 | Canary Islands | 906,978 | N/A | 40 | Guadeloupe | 175,440 | N/A | 75 | Seychelles | 33,220 | 11 | 110 | Monaco | 1826 | 93 |

| 6 | New Zealand | 828,170 | 1078 | 41 | South Africa | 171,240 | 2415 | 76 | Nicaragua | 33,173 | 12 | 111 | Faeroe Islands | 1794 | 184 |

| 7 | Brazil | 800,283 | 25,262 | 42 | Grenada | 170,039 | 14 | 77 | Namibia | 31,449 | 16 | 112 | Iceland | 1794 | 1720 |

| 8 | United Arab Emirates | 738,397 | 4933 | 43 | Costa Rica | 147,621 | 618 | 78 | Morocco | 31,205 | 1888 | 113 | Brunei Darussalam | 1582 | 136 |

| 9 | Puerto Rico | 552,538 | 923 | 44 | Sweden | 135,060 | 11,445 | 79 | Azores | 29,081 | N/A | 114 | Solomon Islands | 1400 | N/A |

| 10 | Italy | 544,543 | 162,488 | 45 | United Kingdom | 134,451 | 93,873 | 80 | Cape Verde Islands | 27,096 | 11 | 115 | St Helena Island | 1200 | N/A |

| 11 | Cayman Islands | 542,079 | 54 | 46 | Dominica | 134,426 | 16 | 81 | Turks & Caicos Islands | 26,507 | 10 | 116 | Gambia | 1197 | 9 |

| 12 | Spain | 514,549 | 172,541 | 47 | Finland | 129,600 | 3161 | 82 | Netherlands | 25,053 | 27,419 | 117 | Guam | 1010 | 135 |

| 13 | St Maarten | 505,762 | 52 | 48 | Vietnam | 122,696 | 274 | 83 | Indonesia | 23,070 | 4839 | 118 | Marshall Islands | 1010 | N/A |

| 14 | Virgin Islands (US) | 496,695 | N/A | 49 | Thailand | 112,445 | 2643 | 84 | Egypt | 22,189 | 2350 | 119 | Samoa | 1000 | N/A |

| 15 | Panama | 471,607 | 3574 | 50 | New Caledonia | 112,187 | 18 | 85 | Papua New Guinea | 18,394 | 2 | 120 | El Salvador | 702 | 159 |

| 16 | Barbados | 439,705 | 73 | 51 | Qatar | 109,429 | 3428 | 86 | Ecuador | 17,714 | 7603 | 121 | St-Martin | 565 | N/A |

| 17 | Argentina | 357,881 | 2432 | 52 | France | 102,854 | 103,573 | 87 | Cyprus | 17,313 | 695 | 122 | Isle of Man | 530 | 242 |

| 18 | St Lucia | 334,828 | 15 | 53 | Hong Kong | 102,458 | N/A | 88 | Israel | 16,264 | 12,046 | 123 | Angola | 462 | 19 |

| 19 | Malaysia | 329,002 | 4987 | 54 | St Vincent | 99,916 | 12 | 89 | Belgium | 15,967 | 31,119 | 124 | Cote d'Ivoire | 462 | 626 |

| 20 | Singapore | 324,471 | 3252 | 55 | India | 92,717 | 11,438 | 90 | Gibraltar | 15,628 | 129 | 125 | Ghana | 462 | 636 |

| 21 | Jamaica | 316,344 | 105 | 56 | Germany | 83,264 | 127,584 | 91 | Bermuda | 14,848 | 57 | 126 | Denmark | 432 | 6511 |

| 22 | Antigua | 294,678 | 23 | 57 | Philippines | 76,473 | 5223 | 92 | Cuba | 13,314 | 766 | 127 | Montserrat | 286 | 11 |

| 23 | Aruba | 288,998 | 92 | 58 | Vanuatu | 72,502 | N/A | 93 | Korea (South) | 12,644 | 10,591 | 128 | Palau | 144 | N/A |

| 24 | Curacao | 287,688 | 14 | 59 | Portugal | 66,018 | 17,448 | 94 | Russia | 11,412 | 21,102 | 129 | Timor-Leste | 120 | 6 |

| 25 | Dominican Republic | 281,210 | 3286 | 60 | Bahrain | 59,661 | 1528 | 95 | Jordan | 5086 | 397 | Total | 26,471,816 | 1,757,368 | |

| 26 | St Kitts & Nevis | 276,311 | 14 | 61 | Taiwan | 57,836 | 395 | 96 | Falkland Islands | 5060 | 11 | ||||

| 27 | Honduras | 270,339 | 419 | 62 | Fiji | 57,190 | 16 | 97 | Croatia | 5036 | 1704 | ||||

| 28 | Uruguay | 255,931 | 533 | 63 | Guatemala | 52,974 | 180 | 98 | Mozambique | 4615 | 28 | ||||

| 29 | Japan | 251,677 | 8100 | 64 | Trinidad & Tobago | 52,056 | 113 | 99 | Tanzania | 4025 | N/A | ||||

| 30 | Martinique | 250,879 | N/A | 65 | Madagascar | 50,682 | 108 | 100 | Tonga | 3716 | N/A | ||||

| 31 | Virgin Islands (British) | 248,096 | N/A | 66 | Haiti | 50,490 | 40 | 101 | Cook Islands | 3246 | N/A | ||||

| 32 | Belize | 246,921 | 18 | 67 | Malta | 46,237 | 393 | 102 | Canada | 3197 | 27,046 | ||||

| 33 | Chile | 212,779 | 7917 | 68 | Peru | 42,583 | 10,303 | 103 | American Samoa | 3000 | N/A | ||||

| 34 | Bonaire | 207,577 | 4 | 69 | Reunion | 42,328 | N/A | 104 | Turkey | 2995 | 65,111 | ||||

| 35 | Oman | 199,333 | 910 | 70 | Sri Lanka | 37,861 | 233 | 105 | Northern Mariana Islands | 2680 | 13 | ||||

The number of cruise passengers landing is from January 1, 2020 to March 31, 2020.

The number of COVID-19 cases is from December 2019 to April 15, 2020.

Source: Cruise passengers landing based on AIS data by authors, COVID-19 case data from European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, An agency of the European Union, 2020.

The US, which had a large number of cruise passengers landing, also had the largest number of COVID-19 cases at 609,516. However, Mexico has the second largest number of cruise passengers with 5399 COVID-19 cases, while Bahamas, with the third largest, has only 49. In addition, Italy, which has a large number of COVID-19 cases, has the 10th largest number of cruise passengers, while Spain ranks 12th and the UK ranks 45th. In other words, countries with the highest number of cruise passengers did not necessarily have the highest number of COVID-19 cases.

3.3. Analyzing the relationship between cruise passengers landing and the COVID-19 outbreak

3.3.1. COVID-19 infection rates between the port of arrival and departure and the port of call

In general, cruise passengers stay in the port city for a few days before embarking or after disembarking a ship. Conversely, the passengers spend only a few hours at the port of call. The time spent by cruise passengers at the arrival and departure ports tends to be longer than the time spent at the port of call. Therefore, we separately analyze the COVID-19 infection rate in countries with arrival and departure ports, and the COVID-19 infection rate in countries with only ports of call.

Unfortunately, AIS data can track ship movements, but not passenger movements. Therefore, we use Expedia (2020) cruise product search website. However, it should be noted that this website does not include cruise products directly sold by some cruise lines and travel agencies. Since our search was conducted in April, the results were different from the ports where ships actually arrived at and departed from January to March. In particular, more countries in the Northern Hemisphere, which have the best season for cruises from April, were included in the search results than countries in the Southern Hemisphere.

As of April 10, 18,501 items of ocean cruise products were sold. Using this site, all cruise products are sorted by port of arrival and departure and by country, as shown in Appendix 2. The US accounted for 43%, followed by Italy, Spain, Canada, France, and Australia. In this analysis, we define these 30 countries as those with ports of arrival and departure.

The data in Table 1 are divided into two groups: one for countries with arrival and departure ports and those without ports. Then, the following two indicators are used for comparison between the port of arrival and departure and the port of call. The first indicator is the number of COVID-19 cases relative to the number of cruise passengers landing. The results are shown in Table 2 . For the country of arrival and departure the figure was 12.85% and for country only at port of call it was 1.50%. It was found that the number of COVID-19 cases against the number of cruise passengers landing at the country of arrival and departure was 11.35% points higher. The second indicator is the COVID-19 infection rate to express the number of COVID-19 cases per population. The COVID-19 infection rate in the country of arrival and departure was 0.057%, while that in the country of port of call was 0.006%. It was found that the COVID-19 infection rate in the country of arrival and departure tended to be 0.051% points higher.

Table 2.

COVID-19 infection rates between countries with arrival and departure ports and countries with only ports of call.

|

Cruise passengers landinga |

Population |

COVID-19 casesb |

COVID-19 cases/passengers landing |

COVID-19 infection rate |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d = c/a | e = c/b | |

| (A) Country of arrival and departure | 12,314,032 | 2,788,910,590 | 1582,558 | 12.85% | 0.057% |

| (B) Country only at port of call | 11,689,288 | 3,023,378,663 | 174,810 | 1.50% | 0.006% |

| (A) - (B) | 624,744 | −234,468,073 | 1,407,748 | 11.35%pt | 0.051%pt |

The number of cruise passengers landing is from January 1, 2020 to March 31, 2020.

The number of COVID-19 cases is from December 2019 to April 15, 2020.

Source: Authors.

Lekakou et al. (2009) proposed that the convenience of an international airport is a necessary condition for cities with arrival and departure ports. Based on an analysis of cruise home ports, Castillo-Manzano et al. (2014) suggested that the likelihood of having cruise traffic was linked to the ports location in populous areas and being close to large airports. In other words, cities with ports of arrival and departure are characterized by proximity to an international airport. Therefore, it should be noted that there are many tourists who are not cruise passengers because of the international airport nearby.

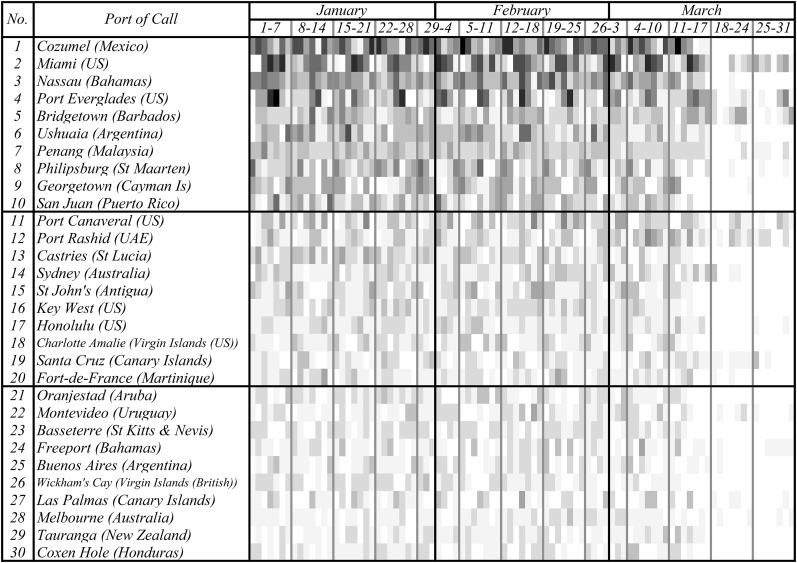

3.3.2. Comparison of port call and COVID-19 infection

There may also be some relationship between the timing of port call and the timing of the COVID-19 outbreak expansion. Fig. 2 shows the number of port calls by day for the top 30 ports from January to March. A dark color filled box indicates a day with many port calls, while white means no port calls in a day. Most of the top 30 ports accepted cruise ships until mid-March when CLIA announced that the cruise ships had stopped operating (CLIA, 2020). In particular, Caribbean ports such as Cozumel (Mexico), Miami (US) and Nassau (Bahamas) continued to accept cruise ships.

Fig. 2.

Number of port calls for each port from January to March.

Note: A dark color filled box indicates a day with many port calls, while white means no port calls in a day.

Source: Authors based on the AIS data.

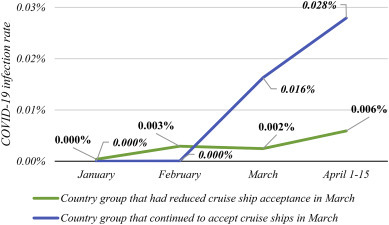

Considering the 14-day incubation period, the number of people infected with COVID-19 in mid-April may be related to the acceptance of cruise ships in March. Therefore, we compare COVID-19 infection rates among countries that had reduced the acceptance of cruise ships in March and those that did not. The 129 countries in Table 1 where cruise ships called from January to March, the number of cruise passengers landing in March was arranged in descending order. These countries are then divided into two groups for analysis. The top half countries are defined as the group that continued to accept cruise ships in March. On the other hand, the lower half countries are defined as the group that had reduced the acceptance of cruise ships in March.

As a result, Fig. 3 shows the COVID-19 infection rate of the former group was 0% in January–February, but increased to 0.016% in March. By the mid-April, it has increased to 0.028%. Conversely, COVID-19 infection rate of the latter group was flat at 0.003% in February, 0.002% in March, and 0.006% in mid-April. The results show that the COVID-19 infection rate in countries that had reduced the acceptance of cruise ships in March was lower than that of the countries that continued to accept cruise ships in March.

Fig. 3.

COVID-19 infection rate for groups accepting cruise ships and reducing cruise ships in March.

Source: Authors.

As shown in Fig. 2, major cruise ports continued to accept cruise ships even until mid-March. This indicates that the decision of stopping a cruise operation cannot be made by each cruise line alone. Similarly, the suspension of port operations also cannot be decided by each port individually. The following viewpoints can offer some reasons.

According to Bagis and Dooms (2014), the purpose of the cruise business is to maximize profits by using ships with huge investments. Suspension of cruise ships will lead to reduced profits and, in the worst case, bankruptcy. According to Henry (2012), general itinerary planning by a cruise line takes place some 2–3 years prior to an actual voyage. If one port is closed, a cruise line cannot immediately call at another port. Due to these circumstances, even if the risk of infection from a cruise ship is increasing, it is not easy for a cruise line to take a management decision to suspend cruise operations.

Even for the port, closing the port is also a difficult decision. One of the reasons for this is the fierce competition between neighboring ports. Recently, the bargaining power on the port side becomes weaker than that of the cruise line. Port closures may lead to the elimination of future port calls. According to Pallis et al. (2018), investment in ports by cruise lines is accelerating. In recent years, cruise lines have invested in ports and have exclusive cruise terminals for their ships. The trend of privatization leads to a decrease in interest in cruises on the port side. Poor interest in the cruise business on the port side may have led to a delay in the decision to close ports.

4. Characteristics of cruise ships with infection on board and the COVID-19 outbreak

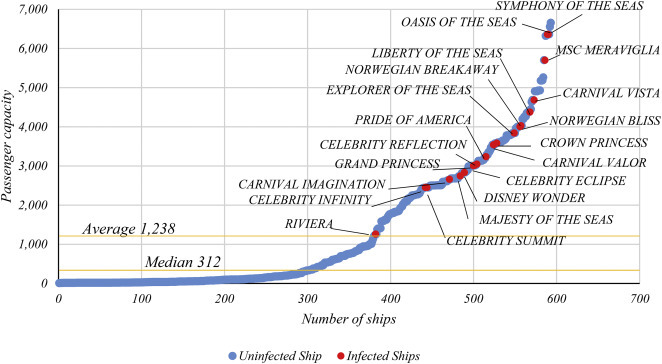

According to the “Cruise ships affected in US by COVID-19” (CDC, 2020b), the cruise ships listed in Appendix 3 made voyages discovered to be infected with COVID-19. We analyze the characteristics of these cruise ships infected with COVID-19 from two perspectives: the ship size and ship operation schedule.

Fig. 4 shows the passenger capacities of cruise ships that were in operation between January and March, which are arranged in order of size of ship. A total of 594 vessels were analyzed, including river cruises. The median and average for all cruise ships are 312 and 1238 passengers, respectively. The passenger capacity of all infected cruise ships was above the median and average. It is clear that cruise ships infected with COVID-19 are large ships.

Fig. 4.

Passenger capacity of cruise ships infected with COVID-19.

Source: Authors.

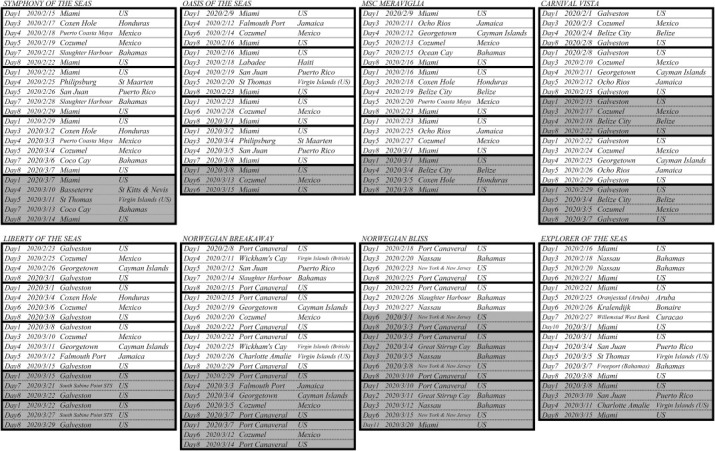

The second indicator is a ship operation schedule (itinerary). Table 3 shows the itinerary of eight large cruise ships before the COVID-19 infection was confirmed. These itineraries had several characteristics. The first is an itinerary that repeats one week for seven nights and eight days. Second is the itinerary, where the arrival and departure port (home port) is fixed. Third, the port of call as a destination is also fixed. These itineraries include private islands owned by each cruise line as ports of call.

Table 3.

Itinerary of cruise ships infected with COVID-19 (top 8 large ships).

Darker color indicates an itinerary infected with COVID-19.

Source: Authors based on AIS data.

The risk of infection on board a ship increases proportionately as the number of passengers increases. Cruise ships with an unspecified number of cruise passengers replacing in a week may have a higher infection rate than ships that do not have passengers replacing for several weeks. In the case of a large cruise ship with many passengers aboard, due to the limited number of persons in charge of inspection, there is a possibility that health inspection may not be strict.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this study is to analyze the relationship between the cruise industry and the COVID-19 outbreak. We analyzed this from two perspectives.

The first analysis focused on the relationship between the cruise ship movement and the COVID-19 outbreak. Consequently, it was found that COVID-19 infection rates in countries that have ports of arrival and departure are higher than in countries with only ports of call. In addition, COVID-19 infection rates in countries that continued to accept cruise ships until March were higher than those in countries that did not. However, we used the estimated number of cruise passengers landing in each country by AIS data to track cruise ships. The estimated figures differ from the actual ones; thus, it is necessary to get the actual data from the cruise lines. The second analysis focused on the characteristics of cruise ships infected with COVID-19. We compared ship sizes and itinerary characteristics from the CDC's list of cruise ships infected with COVID-19. We found that the cruise ships infected with COVID-19 were large. In addition, most cruise ships were sailing from the same home port to the same port of call in a week's time.

The emergence of the modern cruise industry began in the late 1960s and early 1970s (Garin, 2005). The cruise industry has shown remarkable resilience in the face of economic, social political, and other crises. The global financial crisis of 2008–2009 had a serious impact on the maritime cargo shipping industry. However, the cruise industry has continued to grow steadily. When the Costa Concordia loss (2012) created a period of negative publicity for the cruise industry, the industry cruised “through the perfect storm” (Peisley, 2012) and continued to generate more demand in large part due to the successful marketing strategies developed by the cruise lines (Pallis et al., 2018). Vogel and Oschmann (2012) explained that cruise demand has always been “supply-led” starting with the invention of leisure cruising by passenger shipping lines whose scheduled transatlantic services were losing passengers to the airlines. Similarly, Rodrigue and Notteboom (2013) analyzed that the cruise industry works in a “supply push mechanism” as cruise lines aim to generate demand for cruises by providing new products with a larger and more diversified range of ships. The impact of COVID-19 on the cruise industry will be much stronger than any of the past difficulties. However, the cruise industry will grow again with a new supply-driven strategy as overcoming difficulties in the past. We hope that the results of this study will be useful not only for academic researchers, but also for executives of the cruise industry and port officials.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hirohito Ito: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - original draft. Shinya Hanaoka: Supervision, Resources, Writing - review & editing, Validation. Tomoya Kawasaki: Writing - review & editing, Validation.

Contributor Information

Hirohito Ito, Email: hito@central-con.co.jp, ito.h.ax@m.titech.ac.jp.

Shinya Hanaoka, Email: hanaoka@ide.titech.ac.jp.

Tomoya Kawasaki, Email: kawasaki@ide.titech.ac.jp.

Appendix 1. List of cruise areas and countries

| Cruise area | Country |

|---|---|

| North America | Canada, Costa Rica (West coast), El Salvador, Guatemala (West coast), Mexico (West coast), Nicaragua, Panama (West coast), St Pierre and Miquelon, US (North east coast, West coast) |

| Caribbean Sea | Antigua, Aruba, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Cayman Islands, Colombia, Costa Rica (East coast), Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, French Guiana, Grenada, Guadeloupe, Guatemala (East coast), Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Martinique, Mexico (East coast), Montserrat, Netherlands Antilles, Panama (East coast), Puerto Rico, St Kitts & Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent, Suriname, Trinidad & Tobago, Turks & Caicos Islands, US (South east coast), Venezuela, Virgin Islands |

| South America | Argentina, Brazil, Chile (West coast), Ecuador, Falkland Islands, Peru, South Georgia, Uruguay |

| Pacific Ocean | Chile (Around Easter island), US (Around Hawaii islands) |

| Oceania | American Samoa, Australia, Christmas Island, Cook Islands, Fiji, French Polynesia, Guam, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Norfolk Island, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Vanuatu |

| Asia | Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, Myanmar, Philippines, Russia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Timor, Vietnam |

| Middle East, South Asia | Bahrain, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Maldives, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, United Arab Emirates, Yemen |

| Mediterranean Sea | Albania, Algeria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Egypt, France (South coast), Gibraltar, Greece, Israel, Italy (South coast), Lebanon, Libya, Malta, Monaco, Montenegro, Romania, Russia (West coast), Slovenia, Spain (South coast), Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine |

| Northern Europe | Belgium, Channel Islands, Denmark, Estonia, Faroe Islands, Finland, France (North coast), Germany, Greenland, Guernsey, Iceland, Ireland, Isle of Man, Jersey, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Russia (North coast, East coast), Spain, Sweden, UK |

| Africa | Angola, Benin, Cameroon, Canary Islands, Cape Verde Islands, Comoros, Congo (Republic), Cote d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Eritrea, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Madeira, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Reunion, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Western Sahara |

Source: Authors.

Appendix 2. Top 30 countries with ports of arrival and departure among cruise products sold in early April

| Rank | Countries with arrival and departure ports | Number of products | Cumulative Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | 7930 | 42.9% |

| 2 | Italy | 2834 | 58.2% |

| 3 | Spain | 1054 | 63.9% |

| 4 | Canada | 715 | 67.7% |

| 5 | France | 693 | 71.5% |

| 6 | Australia | 467 | 74.0% |

| 7 | Greece | 392 | 76.1% |

| 8 | United Kingdom | 386 | 78.2% |

| 9 | Ecuador | 369 | 80.2% |

| 10 | Denmark | 283 | 81.7% |

| 11 | Germany | 280 | 83.3% |

| 12 | Japan | 272 | 84.7% |

| 13 | Puerto Rico | 266 | 86.2% |

| 14 | Netherlands | 253 | 87.5% |

| 15 | United Arab Emirates | 247 | 88.9% |

| 16 | Singapore | 171 | 89.8% |

| 17 | Brazil | 167 | 90.7% |

| 18 | Argentina | 140 | 91.4% |

| 19 | Barbados | 120 | 92.1% |

| 20 | China | 120 | 92.7% |

| 21 | Turkey | 109 | 93.3% |

| 22 | Sweden | 104 | 93.9% |

| 23 | South Africa | 100 | 94.4% |

| 24 | Hong Kong | 93 | 94.9% |

| 25 | Martinique | 89 | 95.4% |

| 26 | New Zealand | 78 | 95.8% |

| 27 | Portugal | 63 | 96.2% |

| 28 | Norway | 54 | 96.5% |

| 29 | Qatar | 44 | 96.7% |

| 30 | Monaco | 41 | 96.9% |

| Others | 567 | 100.0% | |

| Total | 18,501 | – | |

Source: Authors based on the Expedia, 2020 cruise product search site.

Appendix 3. Cruise ships affected in US by COVID-19

| Ship name | Voyage start date | Voyage end date |

|---|---|---|

| Carnival Imagination | 5-Mar | 8-Mar |

| Carnival Valor | 29-Feb | 5-Mar |

| Carnival Valor | 5-Mar | 9-Mar |

| Carnival Valor | 9-Mar | 14-Mar |

| Carnival Vista | 15-Feb | 22-Feb |

| Carnival Vista | 29-Feb | 7-Mar |

| Celebrity Infinity | 5-Mar | 9-Mar |

| Celebrity Eclipsea | 2-Mar | 30-Mar |

| Celebrity Reflection | 13-Mar | 17-Mar |

| Celebrity Summit | 29-Feb | 7-Mar |

| Crown Princess | 6-Mar | 16-Mar |

| Disney Wonder | 28-Feb | 2-Mar |

| Disney Wondera | 6-Mar | 20-Mar |

| Grand Princess | 11-Feb | 21-Feb |

| Grand Princessa | 21-Feb | 7-Mar |

| MSC Meraviglia | 1-Mar | 8-Mar |

| Norwegian Blissa | 1-Mar | 8-Mar |

| Norwegian Bliss | 8-Mar | 15-Mar |

| Norwegian Breakaway | 29-Feb | 7-Mar |

| Norwegian Breakawaya | 7-Mar | 14-Mar |

| Norwegian Pride of Americaa | 29-Feb | 7-Mar |

| Oceania Rivieraa | 26-Feb | 11-Mar |

| RCCL Explorer of the Seas | 8-Mar | 15-Mar |

| RCCL Liberty of the Seasa | 15-Mar | 29-Mar |

| RCCL Majesty of the Seasa | 29-Feb | 7-Mar |

| RCCL Oasis of the Seasa | 8-Mar | 15-Mar |

| RCCL Symphony of the Seasa | 7-Mar | 14-Mar |

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CDC was notified of COVID-19-positive travelers who had symptoms while on board these ships.

References

- Bagis O., Dooms M. Turkey’s potential on becoming a cruise hub for the East Mediterranean Region: the case of Istanbul. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014;13:6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Manzano J., Fageda X., Gonzalez-Laxe F. An analysis of the determinants of cruise traffic: an empirical application to the Spanish port system. Transp. Res. E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2014;66:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2020a. Public health responses to covid-19 outbreaks on cruise ships — worldwide, February–March 2020. MMWR morbidity and mortality weekly report 2020. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6912e3.htm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) CDC's role in helping cruise ship travelers during the COVID-19 pandemic, cruise ships affected by COVID-19. April 4, 2020. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/cruise-ship/what-cdc-is-doing.html

- Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA), 2020. CLIA Announces Voluntary Suspension in U.S. Cruise Operations. Washington, DC: Cruise Line International Association. Accessed March 25, 2020. https://cruising.org/news-and-research/press-room/2020/march/clia-covid-19-toolkit

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, An agency of the European Union, 2020. COVID-19 cases worldwide. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/download-todays-data-geographic-distribution-covid-19-cases-worldwide

- Expedia, 2020. Accessed April 10, 2020. https://www.expedia.com/Cruise-Search?adultCount=2&sailing-varieties=ocean

- Garin K.A. Plume; New York: 2005. Devils on the Deep Blue Sea: The Dreams, Schemes, and Showdowns That Built America’s Cruise-Ship Empires. [Google Scholar]

- Henry J. In: The Business and Management of Ocean Cruises. Vogel M., et al., editors. CABI; UK: 2012. Itinerary planning; pp. 167–183. [Google Scholar]

- Lekakou M.B., Pallis A.A., Vaggelas G.K. International Association of Maritime Economists Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark. 2009. Is this a home-port? An analysis of the cruise industry’s selection criteria. [Google Scholar]

- Maritime IHS Sea-web ships, movements database. 2020. https://maritime.ihs.com

- Pallis A.A., Parola F., Satta G., Notteboom T.E. Private entry in cruise terminal operations in the Mediterranean Sea. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2018;20:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Peisley T. Seatrade Communications Ltd.; Colchester: 2012. Cruising through the Perfect Storm: Will Draconian New Fuel Regulation in 2015 Change the Cruise industry’s Business Model Forever? [Google Scholar]

- Reuters CORRECTED-UPDATE 3-cruise ships responsible for jump in Australia coronavirus cases. March 24, 2020. 2020. https://jp.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-australia-idUKL4N2BG5A9

- Rodrigue J.P., Notteboom T. Itineraries, not destinations. Appl. Geogr. 2013;38:31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel M., Oschmann C. In: The Business and Management of Ocean Cruises. Vogel M., Papathanassis A., Wolber B., editors. CABI; UK: 2012. The demand for ocean cruises – three perspectives. Organizations: CBI International; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports. Geneva, Switzerland. 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/externalicon