Abstract

Psychiatrists often consider the positive characteristics displayed by a patient in their clinical judgment, yet current assessment and treatment strategies are shifted on the side of psychological dysfunction. Euthymia is a transdiagnostic construct referring to the presence of positive affects and psychological well‐being, i.e., balance and integration of psychic forces (flexibility), a unifying outlook on life which guides actions and feelings for shaping future accordingly (consistency), and resistance to stress (resilience and tolerance to anxiety or frustration). There is increasing evidence that the evaluation of euthymia and its components has major clinical implications. Specific instruments (clinical interviews and questionnaires) may be included in a clinimetric assessment strategy encompassing macro‐analysis and staging. The pursuit of euthymia cannot be conceived as a therapeutic intervention for specific mental disorders, but as a transdiagnostic strategy to be incorporated in an individualized therapeutic plan. A number of psychotherapeutic techniques aiming to enhance positive affects and psychological well‐being (such as well‐being therapy, mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy, and acceptance and commitment therapy) have been developed and validated in randomized controlled clinical trials. The findings indicate that flourishing and resilience can be promoted by specific interventions leading to a positive evaluation of one's self, a sense of continuing growth and development, the belief that life is purposeful and meaningful, satisfaction with one's relations with others, the capacity to manage effectively one's life, and a sense of self‐determination.

Keywords: Euthymia, psychological well‐being, resilience, mental health, clinimetrics, positive psychology, well‐being therapy, mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy

About sixty years ago, M. Jahoda published an extraordinary book on positive mental health1. She denied that “the concept of mental health can be usefully defined by identifying it with the absence of a disease. It would seem, consequently, to be more fruitful to tackle the concept of mental health in its more positive connotation, noting, however, that the absence of disease may constitute a necessary, but not sufficient, criterion for mental health.”1

She outlined criteria for positive mental health: autonomy (regulation of behavior from within), environmental mastery, satisfactory interactions with other people and the milieu, the individual's style and degree of growth, development or self‐actualization, and the attitudes of an individual toward his/her own self (self‐perception/acceptance). The book indicated that mental health research was dramatically weighted on the side of psychological dysfunction1.

It took a long time before such imbalance started being corrected, as a result of several converging developments that occurred in the late 1990s.

First, C. Ryff2 introduced a method for the assessment of Jahoda's psychological dimensions based on the self‐rating Psychological Well‐Being (PWB) scales. This questionnaire disclosed that ill‐being (e.g., major depressive disorder) and well‐being were independent although inter‐related dimensions3, 4. This means that some individuals might have high levels of both ill‐being and well‐being, while others might have major mental disorders and poor psychological well‐being, and further individuals might have no major mental disorders and high levels of psychological well‐being.

Further, the naive conceptualization of well‐being and distress as mutually exclusive (i.e., well‐being is lack of distress and should result from removal of distress) was challenged by clinical research. Patients with a variety of mental disorders who were judged to have remitted on symp‐tomatic grounds still presented with impairment in psychological well‐being compared to healthy control subjects5, 6.

Second, impairments in psychological well‐being were found to be a substantial risk factor for the onset and recurrence of mental disorders, such as depression7, 8. Psychological well‐being thus needs to be incorporated in the definition of recovery9. There has been growing recognition that interventions that bring the person out of negative functioning may not involve a full recovery, but the achievement of a neutral position9. Jahoda1 had postulated that a full recovery can be reached only through interventions which facilitate progress toward restoration or enhancement of psychological well‐being.

A third converging development occurred as the concept of positive mental health became the target of an increasing amount of research10. Its domains were very broad, such as the presence of multiple human strengths (rather than the absence of weaknesses), including maturity, dominance of positive emotions, subjective well‐being, and resilience10.

Yet, probably the strongest input to the consideration of psychological well‐being came from the positive psychology movement initiated by the American Psychological Association in the year 200011, which had a huge impact on psychology and the society in general in a very short time. The movement can be credited with delivering the message that psychology needs to consider the positive as well as the negative, an issue that was much later extended to psychiatry12. Yet, this movement attracted considerable criticism13, 14. Positive psychology developed outside the clinical field and, not surprisingly, its oversimplified approach (happiness and optimism, the more the better) was likely to clash with the complexities of clinical reality13, 14.

Despite these developments, consideration of psychological well‐being has had a limited impact so far on general practice. The aim of this review is to illustrate that clinical attention to psychological well‐being requires an integrative framework, which may be subsumed under the concept of euthymia15, as well as specific assessment and treatment strategies. Such an approach may unravel innovative and promising prospects both in clinical and preventive settings.

EUTHYMIA AS AN INTEGRATIVE FRAMEWORK

In 1991, Garamoni et al16 suggested that healthy functioning is characterized by an optimal balance of positive and neg‐ative cognitions and affects, and that psychopathology is marked by deviations from this balance. Treatment of psychiatric symptoms may induce improvement of well‐being, and, indeed, scales describing well‐being were found to be more sensitive to medication effects than those describing symptoms17. In turn, changes in well‐being may affect the intensity of symptomatology18, 19.

Excessively elevated levels of positive emotions can also become detrimental13, and are more connected with mental disorders and impaired functioning than with psychological well‐being.

Optimal balanced well‐being can be different from person to person, according to factors such as personality traits, social roles, cultural and social context. Table 1 outlines the bipolar nature of Jahoda‐Ryff's dimensions20. Appraisal of positive cognitions and affects thus needs to occur in the setting of an integrative framework, which may be provided by the concept of euthymia.

Table 1.

The spectrum of dimensions of psychological well‐being

| IMPAIRED LEVEL | BALANCED LEVEL | EXCESSIVE LEVEL |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental mastery | ||

| The person feels difficulties in managing everyday affairs; he/she feels unable to improve things around; he/she is unaware of opportunities. | The person has a sense of competence in managing the environment; he/she makes good use of surrounding opportunities; he/she is able to choose what is more suitable to personal needs. | The person is looking for difficult situations to be handled; he/she is unable to savoring positive emotions and leisure time; he/she is too engaged in work or family activities. |

| Personal growth | ||

| The person has a sense of being stuck; he/she lacks sense of improvement over time; he/she feels bored and uninterested in life. | The person has a sense of continued development; he/she sees one's self as growing and improving; he/she is open to new experiences. | The person is unable to elaborate past negative experiences; he/she cultivates illusions that clash with reality; he/she sets unrealistic standards and goals. |

| Purpose in life | ||

| The person lacks a sense of meaning in life; he/she has few goals or aims and lacks sense of direction. | The person has goals in life and feels there is meaning to present and past life. | The person has unrealistic expectations and hopes; he/she is constantly dissatisfied with performance and is unable to recognize failures. |

| Autonomy | ||

| The person is over‐concerned with the expectations and evaluations of others; he/she relies on judgment of others to make important decisions. | The person is independent; he/she is able to resist to social pressures; he/she regulates behavior and self by personal standards. | The person is unable to get along with other people, to work in team, to learn from others; he/she is unable to ask for advice or help. |

| Self‐acceptance | ||

| The person feels dissatisfied with one's self; he/she is disappointed with what has occurred in past life; he/she wishes to be different. | The person accepts his/her good and bad qualities and feels positive about past life. | The person has difficulties in admitting his/her own mistakes; he/she attributes all problems to others’ faults. |

| Positive relations with others | ||

| The person has few close, trusting relationships with others; he/she finds difficult to be open. | The person has trusting relationships with others; he/she is concerned about welfare of others; he/she understands give and take of human relationships. | The person sacrifices his/her needs and well‐being for those of others; low self‐esteem and sense of worthlessness induce excessive readiness to forgive. |

This term has a Greek origin and results from the combination of eu, well, and thymos, soul. The latter element, however, encompasses four different meanings: life energy; feelings and passions; will, desire and inclination; thought and intelligence. Interestingly, the corresponding verb (euthymeo) means both “I am happy, in good spirits” and “I make other people happy”, “I reassure and encourage”.

The definition of euthymia is generally ascribed to Democritus: one is satisfied with what is present and available, taking little heed of people who are envied and admired and observing the lives of those who suffer and yet endure21. It is a state of quiet satisfaction, a balance of emotions that defeats fears.

The Latin philosopher Seneca translated the Greek term euthymia by tranquillitas animi (a state of internal calm and contentment) and linked it to psychological well‐being as a learning process. Happiness is not everything, and what is required is felicitatis intellectus, the awareness of well‐being. Plutarch, who attempted a synthesis of Greek and Latin cultures, criticized the concept of euthymia involving detachment from current events, as portrayed by Epicurus, and underscored the learning potential of mood alterations and adverse life situations.

In the psychiatric literature, the term euthymia essentially connotes the lack of significant distress. When a patient, in the longitudinal course of mood disturbances, no longer meets the threshold for a disorder such as depression or mania, as assessed by diagnostic criteria or by cut‐off points on rating scales, he/she is often labelled as euthymic. Patients with bipolar disorder spend about half of their time in depression, mania or mixed states22. The remaining periods are defined as euthymic23, 24, 25, 26, 27. However, considerable fluctuations in psychological distress were recorded in studies with longitudinal designs, suggesting that the illness is still active in those latter periods, even though its intensity may vary28. It is thus questionable whether subthreshold symptomatic periods truly represent euthymia28.

Similar considerations apply to the use of the term euthymia in unipolar depression and dysthymia. Again, euthymia is often defined essentially in negative terms29, as a lack of a certain intensity of mood symptoms, and not as the presence of specific positive features that characterize recovery9.

Jahoda1 outlined a characteristic that is very much related to the concept of euthymia. She defined it as integration: the individual's balance of psychic forces (flexibility), a unifying outlook on life which guides actions and feelings for shaping future accordingly (consistency), and resistance to stress (resilience and tolerance to anxiety or frustration). It is not simply a generic (and clinically useless) effort of avoiding excesses and extremes. It is how the individual adjusts the psychological dimensions of well‐being to changing needs.

In the past decades, there has been an increasing interest in the concepts of flexibility and resilience portrayed by Jahoda1. Psychological flexibility has been viewed30 as the ability to: recognize and adapt to various situational demands; change one's paradigms when these strategies compromise personal or social functioning; maintain balance among important life domains; display consistency in one's behavior and deeply held values. The absence of flexibility is linked to depression, anxiety and the general tendency to experience negative emotions more frequently, intensely and readily, for longer periods of time, in what has been subsumed under the rubric of neuroticism30.

Resilience has been defined as the capacity to maintain or recover high well‐being in the face of life adversity31. Looking for the presence of wellness following adversity involves a more demanding and rig‐orous conception of resilience than the absence of illness or negative behavioral outcomes, the usual gold standards. Examples are provided by life histories of persons regaining high well‐being following depression, or the ability to sustain psychological well‐being during serious or chronic illness. Resilience is thus conceptualized as a longitudinal and dynamic process, which is related to the concept of flourishing. Issues such as leading a meaningful and purposeful life as well as having quality ties to others affect the physiological substrates of health32. The concept of subjective incompetence (a feel‐ing of being trapped or blocked because of a sense of inability to plan or start actions toward goals) stands as opposite to that of resilience33. Individuals who perceive themselves as incompetent are uncertain and indecisive as to their directions and aims.

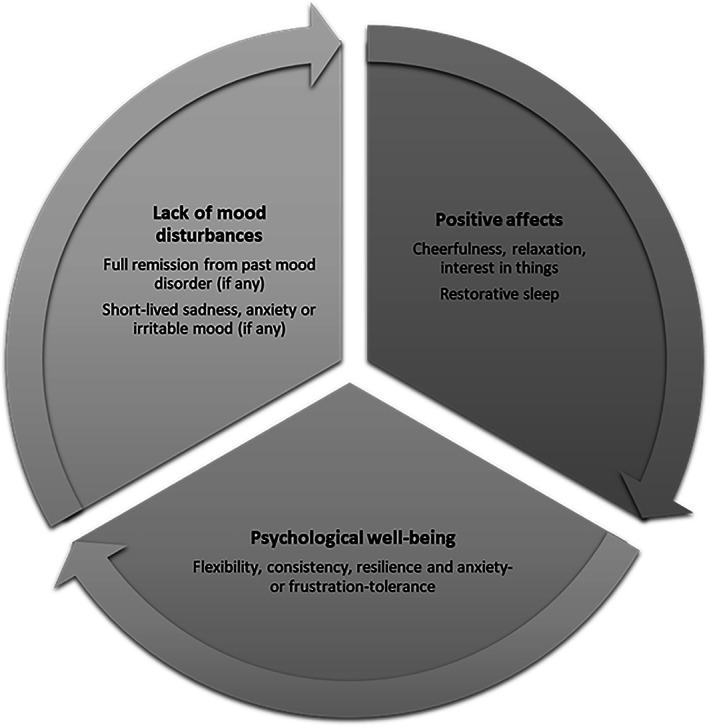

Fava and Bech15 defined a state of euthymia as characterized by the following features (Figure 1):

Lack of mood disturbances that can be subsumed under diagnostic rubrics. If the subject has a prior history of mood disorder, he/she should be in full remission. If sadness, anxiety or irritable mood are experienced, they tend to be short‐lived, related to specific situations, and do not significantly affect everyday life.

The subject has positive affects, i.e., feels cheerful, calm, active, interested in things, and sleep is refreshing or restorative.

The subject manifests psychological well‐being, i.e., displays balance and integration of psychic forces (flexibility), a unifying outlook on life which guides actions and feelings for shaping future accordingly (consistency), and resistance to stress (resilience and tolerance to anxiety or frustration).

Figure 1.

The concept of euthymia

This definition of euthymia, because of its intertwining with mood stability, is substantially different from the concept of eudaimonic well‐being, that has become increasingly popular in positive psychology34. Indeed, research on psychological well‐being can be summarized35 as falling in two general groups: the hedonic viewpoint focuses on subjective well‐being, happiness, pain avoidance and life satisfaction, whereas the eudaimonic viewpoint, as portrayed by Aristotle, focuses on meaning and self‐realization and defines well‐being in terms of degree to which a person is fully functioning or as a set of wellness variables such as self‐actualization and vitality. However, the two viewpoints are inextricably linked in clinical situations, where they also interact with mood fluctuations14. The eudaimonic perspective ignores the complex balance of positive and negative affects in psychological disturbances13, 16.

Whether an individual meets the criteria of euthymia or not, it is important to evaluate its components in clinical practice and to incorporate them in the psychiatric examination. There is, in fact, extensive evidence that positive affects and well‐being represent protective factors for health and increase resistance to stressful life situations6, 32, 36, 37, 38.

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT OF POSITIVE AFFECTS AND PSYCHOLOGICAL WELL‐BEING

Clinical assessment is aimed to exploring the presence of positive affects and psychological well‐being, as well as their interactions with the course and characteristics of symptomatology. In order to analyze these characteristics in an integrative way, we need a clinimetric perspective39, 40, 41. The term “clinimetrics” indicates a domain concerned with the measurement of clinical issues that do not find room in customary clinical taxonomy. Such issues include the types, severity and sequence of symptoms; rate of progression in illness (staging); severity of comorbidity; problems in functional capacity; reasons for medical decisions (e.g., treatment choices), and many other aspects of daily life, such as well‐being and distress39, 40, 41, 42, 43.

Positive affects

While there have been considerable efforts to quantify and qualify psychological distress44, much less has been done about assessing positive affects such as feeling cheerful, calm, active, interested in things, friendly45, 46.

Self‐rating scales and questionnaires have been the preferred method of evaluation, and there are several instruments available45, 46. Two instruments stand out for their clinimetric properties: the World Health Organization‐5 Well‐Being Index (WHO‐5)47 and the Symptom Questionnaire (SQ)17.

The WHO‐5 scale consists of five items that cover a basic life perception of a dynamic state of well‐being. Such items have been incorporated in the Euthymia Scale15, that has been found to entail clinimetric validity and reliability48. The Symptom Questionnaire is a self‐rating scale with 24 items referring to relaxation, contentment, physical well‐being and friendliness, and 68 items referring to anxiety, depression, somatization and hostility‐irritability17. Extensive clinical research has documented its sensitivity to change and ability to discriminate between different populations45.

In their clinical practice, psychiatrists weigh positive affects to evaluate the overall severity and the characteristics of a disorder. For instance, in order to discriminate depression from sadness, psychiatrists look for instances of emotional well‐being that interrupt depressed mood and for reactivity to environmental factors. Indeed, the DSM‐5 requires the presence of depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, for the diagnosis of major depression. Psychiatrists also weigh the intensity of positive emotions and their borders with elation and behavioral activation to determine the bipolar characteristics of a mood disorder. However, current formal assessment strategies fail to capture most of this information49. Table 2 outlines the Clinical Interview for Euthymia (CIE), that covers such missing areas. The first five items explore the contents of positive affects, as depicted by the WHO‐547.

Table 2.

The Clinical Interview for Euthymia (CIE)

| POSITIVE AFFECTS |

| 1. Do you generally feel cheerful and in good spirits? YES NO |

| 2. Do you generally feel calm and relaxed? YES NO |

| 3. Do you generally feel active and vigorous? YES NO |

| 4. Is your daily life filled with things that interest you? YES NO |

| 5. Do you wake up feeling fresh and rested? YES NO |

| DIMENSIONS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL WELL‐BEING |

| Environmental mastery |

| 6. In general, do you feel that you are in charge of the situation in which you live? YES NO |

| 7. Are you always looking for difficult situations and challenges? YES NO |

| Personal growth |

| 8. Do you have the sense that you have developed and matured a lot as a person over the years? YES NO |

| 9. Do you often fail to understand how things go wrong and/or set standards that you are unable to reach? YES NO |

| Purpose in life |

| 10. Do you enjoy making plans for the future and working to make them a reality? In doing this, do you get a sense of direction in your life? YES NO |

| 11. Are you constantly dissatisfied with your performance? YES NO |

| Autonomy |

| 12. Is it more important for you to stand alone on your own principles than to fit in with others? YES NO |

| 13. Are you able to ask for advice or help if needed? YES NO |

| Self‐acceptance |

| 14. In general, do you feel confident and positive about yourself? YES NO |

| 15. Do you have difficulties in admitting your own mistakes, and/or attribute all problems to other people? YES NO |

| Positive relations with others |

| 16. Do you have many people who want to listen when you need to talk and share your concerns, that is, do you feel that you get a lot out of your friendships? YES NO |

| 17. Do you tend to sacrifice your needs and well‐being to those of others? YES NO |

| FLEXIBILITY AND CONSISTENCY |

| 18. If you become sad, anxious or angry, is it for a short time? YES NO |

| 19. Do you keep on thinking of negative experiences? YES NO |

| 20. Are you able to adapt to changing situations? YES NO |

| 21. Do you try to be consistent in your attitudes and behaviors? YES NO |

| 22. Are you able to handle stress most of the times? YES NO |

Psychological well‐being

There are several instruments to assess psychological well‐being states and dimensions45, 46.

The PWB scales have been used extensively in clinical settings6. They encompass 84 items and six dimensions (environmental mastery, personal growth, purpose in life, autonomy, self‐acceptance, and positive relations with others)2. The questionnaire, because of its length, may be problematic to use in a busy clinical setting. A shorter version, the 6‐item part of the PsychoSocial Index50, 51, has been developed and submitted to clinimetric validation: it was found to be a sensitive measure of well‐being, yet it does not allow differentiation of the various dimensions. A structured interview based on the PWB scales2 has also been devised14.

A 10‐item self‐rating scale, the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ‐II), is available to measure psychological flexibility52, 53. Yet, flexibility is only one component of euthymia.

Further, both the PWB scales and derived indices and the AAQ‐II provide assessment of the impaired and optimal levels, but do not yield information about excessive levels. Such information is included in the CIE (Table 2). Items 6 to 17 of the interview assess both polarities of psychological well‐being dimensions developed by Jahoda1 and measured by the PWB scales2. The interview also allows to collect information about flexibility, resilience and consistency (items 18 to 22).

Integration with psychiatric symptomatology

In most instances of diagnostic reasoning in psychiatry, the process ends with the identification of a disorder, according to a diagnostic system. Such a diagnosis (e.g., major depressive disorder), however, encompasses a wide range of manifestations, comorbidity, severity, prognosis and responses to treatment54. The exclusive reliance on diagnostic criteria does not reflect the complex situations that are encountered in clinical practice54. It needs to be integrated with positive affects and psychological well‐being, as well as with a broad range of further elements, including stress, lifestyle, subclinical symptoms, illness behavior and social support, in a longitudinal perspective54.

This approach is in line with the traditional psychopathological assessment, as outlined by M. Roth55: “looking before and after” into the lives of patients, considering the “stressful life circumstances that have surrounded the onset of illness, the premorbid personality and its Achilles heels, the historical record of the patient's development, adjustment in childhood, the relationship with parents, sexual life within and out of marriage, his achievements and ambitions, his interpersonal relationships, his adaptation in various roles and the strength or brittleness of his self‐esteem”55.

Two technical steps may facilitate the integration of the assessments of psychological well‐being and distress.

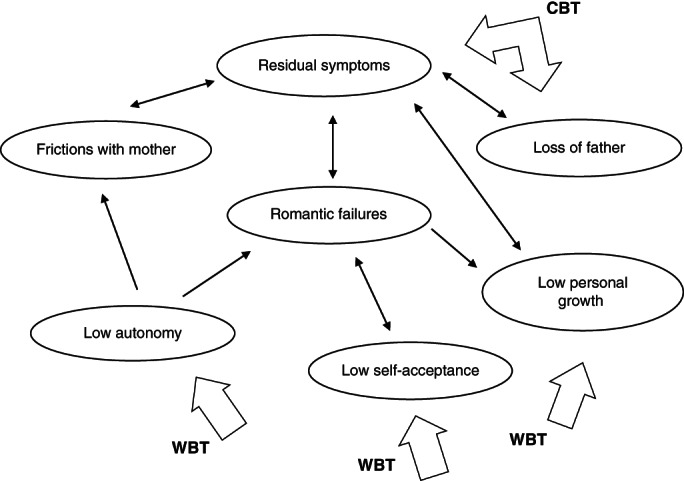

The first technical step involves the clinimetric use of macro‐analysis42, 54, 56. This method starts from the assumption that in most cases of mental disorders there are functional relationships with other more or less clearly defined problem areas, and that the targets of treatment may vary during the course of disturbances. For instance, let us consider the case of a woman with a recurrent major depressive disorder whose current episode has only partially remitted (see Figure 2). Clinical interviewing focused on symptoms may disclose the presence of residual symptoms (e.g., sadness, diminished interest in things, guilt, irritability), problems in the family (e.g., interpersonal frictions with her mother, recurrent thoughts regarding the loss of her father two years before) and unsatisfactory interpersonal relationships (e.g., repeated failures in romantic relationships). Clinical interviewing focused on euthymia may disclose low levels of autonomy (e.g., lack of assertiveness in many situations) and personal growth (e.g., strong feelings of dissatisfaction with her life and a sense of stagnation), and low self‐acceptance (e.g., dissatisfaction with herself). As depicted in Figure 2, macro‐analysis helps to identify the main problem areas in this specific situation.

Figure 2.

Macro‐analysis of a partially remitted patient with recurrent major depressive disorder with therapeutic targets. CBT – cognitive behavior therapy, WBT – well‐being therapy

Macro‐analysis can be supplemented by micro‐analysis, which may consist of dimensional measurements, such as observer‐ or self‐rating scales to assess positive affects and psychological well‐being42, 54, 56. The choice of these instruments is dictated by the clinimetric concept of incremental validity54: each aspect of psychological measurement should deliver a unique increase in information in order to qualify for inclusion.

The second technical step requires reference to the staging method, whereby a disorder is characterized according to severity, extension and longitudinal development57, 58. The clinical meaning linked to the presence of dimensions of psychological well‐being varies according to the stage of development of a disorder, whether prodromal, acute, residual or chronic54. Further, certain psychotherapeutic strategies can be deferred to a residual stage of psychiatric illness, when state‐dependent learning has been improved by the use of medications59. The planning of treatment thus requires determination of the symptomatic target of the first line approach (e.g., pharmacotherapy), and tentative identification of other areas of concern to be addressed by subsequent treatment (e.g., psychotherapy)59.

PSYCHOTHERAPEUTIC TECHNIQUES

Every successful psychotherapy, regardless of its target, is likely to improve subjective well‐being and to reduce symptomatic distress60. Many psychotherapeutic techniques aimed to increase psychological well‐being have been developed, although only a few have been tested in clinical settings61, 62, 63.

A specific psychotherapeutic strategy has been developed according to Jahoda's concept of euthymia1. Well‐being therapy (WBT) is a manualized, short‐term psychotherapeutic strategy that emphasizes self‐observation, with the use of a structured diary, homework and interaction between patient and therapist14, 20, 64. It can be differentiated from positive psychology interventions62 on the basis of the following features: a) patients are encouraged to identify episodes of well‐being and to set them into a situational context; b) once the instances of well‐being are properly recognized, the patient is encouraged to identify thoughts and beliefs leading to premature interruption of well‐being (automatic thoughts), as is performed in cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) but focusing on well‐being rather than distress; c) the therapist may also reinforce and encourage activities that are likely to elicit well‐being; d) the monitoring of the course of episodes of well‐being allows the therapist to identify specific impairments or excessive levels in well‐being dimensions according to Jahoda's conceptual framework1; e) patients are not simply encouraged to pursue the highest possible levels of psychological well‐being in all dimensions, as is the case in most positive psychology interventions, but also to achieve a balanced functioning15.

Another psychotherapeutic strategy intended to increase psychological well‐being is mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy (MBCT)65, which is built on the Buddhist philosophy of a good life. Its main aim is to reduce the impact of potentially distressing thoughts and feelings, but it also introduces techniques such as mindful, non‐judgmental attention and mastery, and pleasure tasks that may be geared to a good life66. However, the good life that is strived for is a state involving detachment, as portrayed by Epicurus, and not necessarily euthymia, as depicted by Plutarch.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)67 is aimed to increase psychological flexibility53. It consists of an integration of behavioral theories of change with mindfulness and acceptance strategies. Unlike WBT, ACT argues that attempts at changing thoughts can be counterproductive, and encourages instead awareness and acceptance through mindfulness practice.

There are also further psychotherapeutic approaches, such as Padesky and Mooney's strengths‐based CBT68 and forgiveness therapy69, that have been suggested to increase well‐being, but await adequate clinical validation66.

APPLICATIONS

The pursuit of euthymia in a clinical setting cannot be conceived as a therapy for specific mental disorders, but as a transdiagnostic strategy to be incorporated in a therapeutic plan. Psychotherapeutic interventions aimed at psychological well‐being are not suitable for application as a first line treatment of an acute psychiatric disorder20, 64. However, most patients seen in clinical practice have complex and chronic disorders54. It is simply wishful thinking to believe that one course of treatment will be sufficient for yielding lasting and satisfactory remission. The use of psychotherapeutic strategies aimed at euthymia should thus follow clinical reasoning and case formulation facilitated by the use of macro‐analysis and staging.

The treatment plan should be filtered by clinical judgment taking into consideration a number of clinical variables, such as the characteristics and severity of the psychiatric episode, co‐occurring symptomatology and problems (not necessarily syndromes), medical comorbidities, patient's history, and levels of psychological well‐being54. Such information should be placed among other therapeutic ingredients, and will need to be integrated with patient's preferences70.

In the following sections, we illustrate a number of applications of strategies for enhancing and/or modulating psychological well‐being. All these indications should be seen as tentative since, even when efficacy is supported by randomized controlled trials, the specific role of strategies modulating well‐being in determining the outcome cannot be elucidated with certainty, because they are incorporated within more traditional approaches and a dismantling analysis is rarely implemented.

Relapse prevention

In 1994, a randomized controlled trial introduced the sequential design in depression71. Depressed patients who had responded to pharmacotherapy were randomly assigned to CBT or to clinical management, while antidepressant medications were tapered and discontinued. This design was subsequently used in a number of randomized controlled trials and was found to entail significant benefits in a meta‐analysis72.

The sequential model is an intensive, two‐stage approach, where one type of treatment (psychotherapy) is applied to improve symptoms which another type of treatment (pharmacotherapy) was unable to affect. The rationale for this approach is to use psychotherapeutic strategies when they are most likely to make a unique and separate contribution to patient's well‐being and to achieve a more pervasive recovery by addressing residual symptomatology. The sequential design is different from maintenance strategies for prolonging clinical responses obtained by therapies in the acute episodes, as well as from augmentation or switching strategies addressing lack of response to the first line of treatment71, 72.

Three independent randomized controlled trials using the sequential combination of cognitive therapy and WBT were performed in Italy73, 74, Germany75 and the US76. In other trials that took place in Canada77 and the Netherlands78, some principles of WBT were used in addition to standard cognitive therapy. Further, there have been several investigations79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87 in which MCBT was applied to the residual stage of depression after pharmacotherapy.

From the available studies, we are unable to detect whether the pursuit of psychological well‐being was a specific effective ingredient and what was the mechanism decreasing the likelihood of relapse. Nonetheless, the clinical results that have been obtained are impressive, and the sequential model seems to be a strategy that has enduring effects in the prevention of the vexing problem of relapse in depression. It is conceivable, and yet to be tested, that similar strategies may involve significant advantages in terms of relapse rates also in other psychiatric disorders.

Increasing the level of recovery

The studies that used a sequential design clearly indicated that the level of remission obtained by successful pharmacotherapy could be increased by a subsequent psychotherapeutic treatment72. Clinicians and researchers in clinical psychiatry often confound response to treatment with full recovery9. A full recovery can be reached only through interventions which facilitate progress toward restoration or enhancement of psychological well‐being1.

In a randomized controlled trial, patients with mood or anxiety disorders who had been successfully treated by behavioral (anxiety disorders) or pharmacological (mood disorders) methods were assigned to either WBT or CBT for residual symptoms18. Both WBT and CBT were associated with a significant reduction of those symptoms, but a significant advantage of WBT over CBT was detected by observer‐rated methods. WBT was associated also with a significant increase in PWB scores, particularly in the personal growth scale18.

A dismantling study in generalized anxiety disorder19 suggested that an increased level of recovery could indeed be obtained with the addition of WBT to CBT. Patients were randomly assigned to eight sessions of CBT, or to CBT followed by four sessions of WBT. Both treatments were associated with a significant reduction of anxiety. However, significant advantages of the CBT/WBT sequential combination over CBT were observed, both in terms of symptom reduction and psychological well‐being improvement19.

While the clinical benefits of WBT in increasing the level of recovery have been documented in depression64 and generalized anxiety disorder19, this appears to be a possible target for a number of other mental health problems. Indeed, the issue of personal growth is attracting increasing interest in psychoses88, and a role for WBT in improving functional outcomes as an additional ingredient to CBT in psychotic disorders has been postulated89.

Modulating mood

WBT has been applied in cyclothymic disorder90, a condition that involves mild or moderate fluctuations of mood, thoughts and behavior without meeting formal diagnostic criteria for either major depressive disorder or mania.

Patients with cyclothymic disorder were randomly assigned to the sequential combination of CBT and WBT or clinical management. At post‐treatment, significant differences were found in outcome measures, with greater improvements in the CBT/WBT group. Therapeutic gains were maintained at 1‐ and 2‐ year follow‐up.

The results thus indicated that WBT may address both polarities of mood swings and is geared to a state of euthymia15. Can the target of euthymia decrease vulnerability to relapse in bipolar spectrum disorders91? This is an important area that deserves specific studies.

Treatment resistance

A considerable number of patients fail to respond to appropriate pharmacotherapy and/or psychotherapy54. In a randomized controlled trial, MBCT was compared to treatment‐as‐usual (TAU) in treatment‐resistant depression92. MBCT was significantly more efficacious than TAU in reducing depression severity, but not the number of cases who remitted.

A subsequent study93 investigated the effectiveness of MBCT + TAU versus TAU only for chronic, treatment‐resistant depressed patients who had not improved during not only previous pharmacotherapy but also psychological treatment (i.e., CBT or interpersonal psychotherapy). At post‐treatment, MBCT + TAU had significant beneficial effects in terms of remission rates, quality of life, mindfulness skills, and self‐compassion, even though the intent to treat (ITT) analysis did not reveal a significant reduction in depressive symptoms.

A number of case reports have suggested that WBT may provide a viable alternative when standard cognitive techniques based on monitoring distress do not yield any improvement or even cause symptomatic worsening in depression, panic disorder, or anorexia nervosa64. These data are insufficient to postulate a role for psychotherapies enhancing or modulating psychological well‐being in these patient populations, yet this approach may yield new insights into this area.

Suicidal behavior

The relationship between future‐directed thinking (prospection) and suicidality has been recently analyzed94, and a potential innovative role for well‐being enhancing psychotherapies has been postulated. Working on dimensions such as purpose in life may counteract suicidal behavior. Indeed, positive mental health was found to moderate the association between suicidal ideation and suicide attempts95.

An issue that is not sufficiently appreciated is also the experience of mental pain that many suicidal patients may present. ACT was found to significantly reduce suicidal ideation as well as mental pain compared to relaxation in adult suicidal patients96.

Discontinuing psychotropic drugs

Psychotropic drug treatment, particularly when it is protracted in time, may cause various forms of dependence97. Withdrawal symptoms do not necessarily wane after drug discontinuation and may build into persistent post‐withdrawal disorders98. These symptoms may constitute a iatrogenic comorbidity that affects the course of illness and the response to subsequent treatments97.

Discontinuation of antidepressant medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, duloxetine and venlafaxine represents a major clinical challenge99, 100. A protocol based on the sequential combination of CBT and WBT in post‐withdrawal disorders has been devised101 and tested in case reports102.

Post‐traumatic stress disorder

There has been growing awareness of the fact that traumatic experiences can also give rise to positive developments, subsumed under the rubric of post‐traumatic growth103. Positive changes can be observed in self‐concept (e.g., new evaluation of one's strength and resilience), appreciation of life opportunities, social relations, hierarchy of values and priorities, spiritual growth.

Well‐being enhancing strategies may be uniquely suited for facilitating the process of post‐traumatic growth. Two cases have been reported on the use of WBT, alone or in sequential combination with exposure, for overcoming post‐traumatic stress disorder, with the central trauma being discussed only in the initial history‐taking session104.

Improving medical outcomes

The need to include consideration of psychosocial factors (functioning in daily life, quality of life, illness behavior) has emerged as a crucial component of patient care in chronic medical diseases37. These aspects also extend to family caregivers of chronically ill patients and health providers36. There has also been recent interest in the relationship between psychological flexibility and chronic pain105. It is thus possible to postulate a role for psychotherapeutic interventions modulating psychological well‐being in the setting of medical diseases, to counteract the limitations and challenges induced by illness experience. The process of rehabilitation, in fact, requires the promotion of well‐being and changes in lifestyle as primary targets of intervention106.

In recent years, there has been increasing evidence suggesting that stressful conditions may elicit a pattern of conserved transcriptional response to adversity (CTRA), in which there is an increased expression of pro‐inflammatory genes and a concurrent decreased expression of type 1 interferon innate antiviral response and IgG antibody synthesis107. Such patterns have been implicated in the pathophysiology of cancer108 and cardiovascular diseases109. Frederickson et al110 reported that individuals with high psychological well‐being presented reduced CTRA gene expression, which introduces a potential protective role for psychological well‐being in a number of medical disorders.

Improving health attitudes and behavior

Unhealthy lifestyle (e.g., smoking, physical inactivity, excessive eating) is a major risk factor for many of the most prevalent medical and psychiatric diseases36, 111. Lifestyle modification focused on weight reduction, increased physical activity, and dietary change is recommended as first line therapy in a number of disorders, yet psychological distress and low levels of well‐being are commonly observed among patients with chronic conditions and represent important obstacles to behavioral change36.

It has been argued that enduring lifestyle changes can only be achieved with a personalized approach that targets psychological well‐being112. As a result, strategies pointing to euthymia need to be tested in lifestyle interventions and in the prevention of mental and physical disorders.

CONCLUSIONS

Customary clinical taxonomy and evaluation do not include psychological well‐being, which may demarcate major prognostic and therapeutic differences among patients who otherwise seem to be deceptively similar since they share the same diagnosis. A number of psychotherapeutic strategies aimed to increase positive affects and psychological well‐being have been developed. WBT, MBCT and ACT have been found effective in randomized controlled clinical trials.

An important characteristic of WBT is having euthymia as a specific target. This perspective is different from interventions that are labelled as positive but are actually distress oriented. An additional novel area in psychotherapy research can ensue from exploring euthymia as a characteristic of successful psychotherapists, as the Greek verb equivalent implies.

The evidence supporting the clinical value of the pursuit of euthymia is still limited. However, the insights gained may unravel innovative approaches to the assessment and treatment of mental disorders, with particular reference to decreasing vulnerability to relapse, increasing the level of recovery, and modulating mood.

These fascinating developments should be welcome by all those who are disillusioned with the current long‐term outcomes of mental disorders. These outcomes may be unsatisfactory not because technical interventions are missing, but because our conceptual models, shifted on the side of psychological dysfunction, are inadequate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jahoda M. Current concepts of positive mental health. New York: Basic Books, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well‐being. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989;6:1069‐81. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singer BH, Ryff CD, Carr D et al. Life histories and mental health: a person‐centered strategy In: Raftery A. (ed). Sociological methodology. Washington: American Sociological Association, 1998:1‐51. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Keyes CLM. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav 2002;43:207‐22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rafanelli C, Park SK, Ruini C et al. Rating well‐being and distress. Stress Med 2000;16:55‐61. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ryff CD. Psychological well‐being revisited. Psychother Psychosom 2014;83:10‐28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wood AM, Joseph S. The absence of positive psychological (eudemonic) well‐being as a risk factor for depression: a ten‐year cohort study. J Affect Disord 2010;122:213‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Risch AK, Taeger S, Brüdern J et al. Psychological well‐being in remitted patients with recurrent depression. Psychother Psychosom 2013;82:404‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fava GA, Ruini C, Belaise C. The concept of recovery in major depression. Psychol Med 2007;37:307‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vaillant GE. Positive mental health: is there a cross‐cultural definition? World Psychiatry 2012;11:93‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: an introduction. Am Psychol 2000;55:5‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jeste DV, Palmer BW. Positive psychiatry. A clinical handbook. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wood AM, Tarrier N. Positive clinical psychology. Clin Psychol Rev 2010;30:819‐29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fava GA, Tomba E. Increasing psychological well‐being and resilience by psychotherapeutic methods. J Pers 2009;77:1902‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fava GA, Bech P. The concept of euthymia. Psychother Psychosom 2016;85:1‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garamoni GL, Reynolds CF 3rd, Thase ME. The balance of positive and negative affects in major depression: a further test of the states of the mind model. Psychiatry Res 1991;39:99‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kellner R. A symptom questionnaire. J Clin Psychiatry 1987;48:269‐74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fava GA, Rafanelli C, Cazzaro M et al. Well‐being therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic approach for residual symptoms of affective disorders. Psychol Med 1998;28:475‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fava GA, Ruini C, Rafanelli C et al. Well‐being therapy of generalized anxiety disorder. Psychother Psychosom 2005;74:26‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fava GA. Well‐being therapy. Treatment manual and clinical applications. Basel: Karger, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kahn CH. Democritus and the origins of moral psychology. Am J Philol 1985;106:1‐31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ et al. The long‐term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:530‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Blumberg HP. Euthymia, depression, and mania: what do we know about the switch? Biol Psychiatry 2012;71:570‐1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martini DJ, Strejilevich SA, Marengo E et al. Toward the identification of neurocognitive subtypes in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2014;167:118‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Canales‐Rodriguez EJ, Pomarol‐Clotet E, Radua J et al. Structural abnormalities in bipolar euthymia. Biol Psychiatry 2014;76:239‐48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hannestad JO, Cosgrove KP, Dellagioia NF et al. Changes in the cholinergic system between bipolar depression and euthymia as measured with [123I]5IA single photon emission computed tomography. Biol Psychiatry 2013;74:768‐76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rocha PM, Neves FS, Correa H. Significant sleep disturbances in euthymic bipolar patients. Compr Psychiatry 2013;54:1003‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fava GA. Subclinical symptoms in mood disorders: pathophysiological and therapeutic implications. Psychol Med 1999;29:47‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dunner DL. Duration of periods of euthymia in patients with dysthymic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1992‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kashdan TB, Rottenberg J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin Psychol Rev 2010;30:865‐78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ryff CD, Singer B, Dienbery Love G et al. Resilience in adulthood and later life In: Lomranz J. (ed). Handbook of aging and mental health. New York: Plenum, 1998:69‐96. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hasler G. Well‐being: an important concept for psychotherapy and psychiatric neuroscience. Psychother Psychosom 2016;85:255‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. de Figueiredo JM, Frank JD. Subjective incompetence, the clinical hallmark of demoralization. Compr Psychiatry 1982;23:353‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huta V. Eudaimonia In: David SA, Boniwell I, Conley Ayers A. (eds). The Oxford handbook of happiness. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013:200‐13. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ryan RM, Deci EL. On happiness and human potential: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well‐being. Annu Rev Psychol 2001;52:141‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fava GA, Cosci F, Sonino N. Current psychosomatic practice. Psychother Psychosom 2017;86:13‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fava GA, Sonino N. From the lesson of George Engel to current knowledge: the biopsychosocial model 40 years later. Psychother Psychosom 2017;86:257‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McEwen BS. Epigenetic interactions and the brain‐body communication. Psychother Psychosom 2017;86:1‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Feinstein AR. Clinimetrics. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fava GA, Tomba E, Sonino N. Clinimetrics: the science of clinical measurements. Int J Clin Pract 2012;66:11‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fava GA, Carrozzino D, Lindberg L et al. The clinimetric approach to psychological assessment. Psychother Psychosom 2018;87:321‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fava GA, Sonino N, Wise TN. The psychosomatic assessment. Basel: Karger, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fava GA, Tomba E, Bech P. Clinical pharmacopsychology. Psychother Psychosom 2017;86:134‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bech P. Clinical psychometrics. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rafanelli C, Ruini C. Assessment of psychological well‐being in psychosomatic medicine In: Fava GA, Sonino N, Wise TN. (eds). The psychosomatic assessment. Basel: Karger, 2012:182‐202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bech P. Clinical assessments of positive mental health In: Jeste DV, Palmer BW. (eds). Positive psychiatry. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2015:127‐43. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Topp CW, Ostergaard SD, Sondergaard S et al. The WHO‐5 well‐being index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom 2015;84:167‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Carrozzino D, Svicher A, Patierno C et al. The Euthymia Scale: a clinimetric analysis. Psychother Psychosom 2019;88:119‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zimmerman M, Morgan TA, Stanton K. The severity of psychiatric disorders. World Psychiatry 2018;17:258‐75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sonino N, Fava GA. A simple instrument for assessing stress in clinical practice. Postgrad Med J 1998;74:408‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Piolanti A, Offidani O, Guidi J et al. Use of the PsychoSocial Index (PSI), a sensitive tool in research and practice. Psychother Psychosom 2016;85:337‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer R et al. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire II: a revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behav Ther 2011;42:676‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fledderus M, Bohlmeijer ET, Fox JP et al. The role of psychological flexibility in a self‐help acceptance and commitment therapy intervention for psychological distress in a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 2013;51:142‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fava GA, Rafanelli C, Tomba E. The clinical process in psychiatry. J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:177‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Roth M. Some recent developments in relation to agoraphobia and related disorders and their bearing upon theories of their causation. Psychiatr J Univ Ott 1987;12:150‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Emmelkamp PMG, Bouman TK, Scholing A. Anxiety disorders. Chichester: Wiley, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fava GA, Kellner R. Staging: a neglected dimension in psychiatric classification. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993;87:225‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cosci F, Fava GA. Staging of mental disorders: systematic review. Psychother Psychosom 2013;82:20‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Guidi J, Tomba E, Cosci F et al. The role of staging in planning psychotherapeutic interventions in depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2017;78:456‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Howard KI, Lueger RJ, Maling MS et al. A phase model of psychotherapy outcome: causal mediation of change. J Consult Clin Psychol 1993;61:678‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rashid T. Positive psychology in practice: positive psychotherapy In: David SA, Boniwell I, Conley Ayers A. (eds). The Oxford handbook of happiness. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013:978‐93. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Quoidbach J, Mikolajczak M, Gross JJ. Positive interventions: an emotion regulation perspective. Psychol Bull 2015;141:655‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Weiss LA, Westerhof GJ, Bohlmeijer ET. Can we increase psychological well‐being? The effects of interventions on psychological well‐being. PLoS One 2016;11:e0158092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fava GA, Cosci F, Guidi J et al. Well‐being therapy in depression: new insights into the role of psychological well‐being in the clinical process. Depress Anxiety 2017;34:801‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy for depression. New York: Guilford, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 66. MacLeod AK, Luzon O. The place of psychological well‐being in cognitive therapy In: Fava GA, Ruini C. (eds). Increasing psychological well‐being in clinical and educational settings. Dordrecht: Springer, 2014:41‐55. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hayes SC, Strosahal K, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy. New York: Guilford, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Padesky CA, Mooney K. Strengths based cognitive‐behavioural therapy. Clin Psychol Psychother 2012;19:283‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Enright RD, Fitzgibbons RP. Forgiveness therapy. Washington: American Psychological Association, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Guidi J, Brakemeier EL, Bockting CLH et al. Methodological recommendations for trials of psychological interventions. Psychother Psychosom 2018;87:285‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Fava GA, Grandi S, Zielezny M et al. Cognitive behavioral treatment of residual symptoms in primary major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:1295‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Guidi J, Tomba E, Fava GA. The sequential integration of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a meta‐analysis of the sequential model and a critical review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173:128‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Fava GA, Rafanelli C, Grandi S et al. Prevention of recurrent depression with cognitive behavioral therapy: preliminary findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:816‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Fava GA, Ruini C, Rafanelli C et al. Six‐year outcome of cognitive behavior therapy for prevention of recurrent depression. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1872‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Stangier U, Hilling C, Heidenreich T et al. Maintenance cognitive‐behavioral therapy and manualized psychoeducation in the treatment of recurrent depression: a multicenter prospective randomized controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170:624‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kennard BD, Emslie GJ, Mayes TL et al. Sequential treatment with fluoxetine and relapse‐prevention CBT to improve outcomes in pediatric depression. Am J Psychiatry 2014;171:1083‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Farb N, Anderson A, Ravindran A et al. Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depressive disorder with either mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy or cognitive therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 2018;88:200‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bockting CL, Klein NS, Elgersma HJ et al. The effectiveness of preventive cognitive therapy while tapering antidepressants compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment and their combination in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (DRD study). Lancet Psychiatry 2018;5:401‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Bondolfi G, Jermann F, der Linden MV et al. Depression relapse prophylaxis with mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy: replication and extension in the Swiss health care system. J Affect Disord 2010;122:224‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Godfrin KA, van Heeringen C. The effects of mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy on recurrence of depressive episodes, mental health and quality of life: a randomized controlled study. Behav Res Ther 2010;48:738‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kuyken W, Byford S, Taylor RS et al. Mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy to prevent relapse in recurrent depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008;76:966‐78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Ma SH, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy for depression: replication and exploration of differential relapse prevention effects. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004;72:31‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Segal ZV, Bieling P, Young T et al. Antidepressant monotherapy vs sequential pharmacotherapy and mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy, or placebo, for relapse prophylaxis in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:1256‐64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, Williams JMG et al. Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000;68:615‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Williams JMG, Crane C, Barnhofer T et al. Mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy for preventing relapse in recurrent depression: a randomized dismantling trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2014;82:275‐86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kuyken W, Hayes R, Barrett B et al. Effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (PREVENT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386:63‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Huijbers MJ, Spinhoven P, Spijker J et al. Discontinuation of antidepressant medication after mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy for recurrent depression: randomised controlled non‐inferiority trial. Br J Psychiatry 2016;208:366‐73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Slade M, Blacke L, Longden E. Personal growth in psychosis. World Psychiatry 2019;18:29‐30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Penn DL, Mueser KT, Tarrier N et al. Supportive therapy for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2004;30:101‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Fava GA, Rafanelli C, Tomba E et al. The sequential combination of cognitive behavioral treatment and well‐being therapy in cyclothymic disorder. Psychother Psychosom 2011;80:136‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Nierenberg AA. An analysis of the efficacy of treatments for bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69(Suppl. 5):4‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Eisendrath SJ, Gillung E, Delucchi KL et al. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy for treatment‐resistant depression. Psychother Psychosom 2016;85:99‐110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Cladder‐Micus MB, Speckens AEM, Vrijsen JN et al. Mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy for patients with chronic, treatment‐resistant depression: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Depress Anxiety 2018;35:914‐24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. MacLeod AK. Suicidal behavior. The power of prospection In: Wood AM, Johnson J. (eds). The Wiley handbook of positive clinical psychology. Chichester: Wiley, 2016:293‐304. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Brailovskaia J, Forkmann T, Glaesmer H et al. Positive mental health moderates the association between suicide ideation and suicide attempts. J Affect Disord 2019;245:246‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Ducasse D, Jaussent I, Arpon‐Brand V et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for the management of suicidal patients: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom 2018;87:211‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Fava GA, Cosci F, Offidani E et al. Behavioral toxicity revisited: iatrogenic comorbidity in psychiatric evaluation and treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2016;36:550‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Chouinard G, Chouinard VA. New classification of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) withdrawal. Psychother Psychosom 2015;84:63‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Fava GA, Gatti A, Belaise C et al. Withdrawal symptoms after selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom 2015;84:72‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Fava GA, Benasi G, Lucente M et al. Withdrawal symptoms after serotonin‐noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor discontinuation: systematic review. Psychother Psychosom 2018;87:195‐203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Fava GA, Belaise C. Discontinuing antidepressant drugs. Psychother Psychosom 2018;87:257‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Belaise C, Gatti A, Chouinard VA et al. Persistent postwithdrawal disorders induced by paroxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and treated with specific cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychother Psychosom 2014;83:247‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Vazquez C, Pérez‐Sales P, Ochoa C. Post‐traumatic growth In: Fava GA, Ruini C. (eds). Increasing psychological well‐being in clinical and educational settings. Dordrecht: Springer, 2014:57‐74. [Google Scholar]

- 104. Belaise C, Fava GA, Marks IM. Alternatives to debriefing and modifications to cognitive behavior therapy for post‐traumatic stress disorder. Psychother Psychosom 2005;74:212‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. McCracken LM, Morley S. The psychological flexibility model: a basis for the integration and progress in psychological approaches to chronic pain management. J Pain 2014;15:221‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Nierenberg B, Mayersohn G, Serpa S et al. Application of well‐being therapy to people with disability and chronic illness. Rehab Psychol 2016;61:32‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Cole SW. Human social genomics. PLoS Genet 2014;10:e1004601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Currier MB, Nemeroff CB. Depression as a risk factor for cancer. Annu Rev Med 2014;65:203‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Nemeroff CB, Goldschmidt‐Clermont PJ. Heartache and heartbreak – the link between depression and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2012;9:526‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Frederickson BL, Grewen KM, Algoes SB et al. Psychological well‐being and the human conserved transcriptional response to adversity. PLoS One 2015;10:e0121839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Sartorius N, Holt RIG, Maj M. (eds). Comorbidity of mental and physical disorders. Basel: Karger, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 112. Guidi J, Rafanelli C, Fava GA. The clinical role of well‐being therapy. Nord J Psychiatry 2018;72:447‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]