Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: Africa, human immunodeficiency virus, lost to follow-up, Mozambique, reengagement in care, retention in care

Abstract

Patients lost to follow-up (LTFU) over the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cascade have poor clinical outcomes and contribute to onward HIV transmission. We assessed true care outcomes and factors associated with successful reengagement in patients LTFU in southern Mozambique.

Newly diagnosed HIV-positive adults were consecutively recruited in the Manhiça District. Patients LTFU within 12 months after HIV diagnosis were visited at home from June 2015 to July 2016 and interviewed for ascertainment of outcomes and reasons for LTFU. Factors associated with reengagement in care within 90 days after the home visit were analyzed by Cox proportional hazards model.

Among 1122 newly HIV-diagnosed adults, 691 (61.6%) were identified as LTFU. Of those, 557 (80.6%) were approached at their homes and 321 (57.6%) found at home. Over 50% had died or migrated, 10% had been misclassified as LTFU, and 252 (78.5%) were interviewed. Following the visit, 79 (31.3%) reengaged in care. Having registered in care and a shorter time between LTFU and visit were associated with reengagement in multivariate analyses: adjusted hazards ratio of 3.54 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.81–6.92; P < .001] and 0.93 (95% CI: 0.87–1.00; P = .045), respectively. The most frequently reported barriers were the lack of trust in the HIV-diagnosis, the perception of being in good health, and fear of being badly treated by health personnel and differed by type of LTFU.

Estimates of LTFU in rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa are likely to be overestimated in the absence of active tracing strategies. Home visits are resource-intensive but useful strategies for reengagement for at least one-third of LTFU patients when applied in the context of differentiated care for those LTFU individuals who had already enrolled in HIV care at some point.

1. Introduction

Patients lost to follow-up (LTFU) at different stages of the HIV cascade may increase HIV transmission, mortality, and morbidity rates as well as hinder efforts to control the HIV epidemic.[1,2] LTFU is particularly common in low-income countries, where health systems and patients face many barriers to care.[3,4,5] In 2016, national estimates for Mozambique showed that retention in care after 3 years on antiretroviral therapy (ART) was 44%.[6] However monitoring of LTFU and retention is challenging due to inadequate health information systems and to patient behavior, which often involves patients cycling in and out of care.[7,8]

There is little information on long-term retention in ART programs and reengagement in care after LTFU.[4] The published literature shows that active tracking of patients, via phone calls, short text message reminders, letters, or home visits, can reduce program attrition both in high- and low-income countries.[9,10,11,12,13,14] Although most countries recommend tracing LTFU patients, it can be costly, and thus context-specific strategies and evidence on specific populations who could benefit from reengagement in care interventions are needed.

Several studies in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) have identified societal and individual factors, as well as weak health systems as leading causes of attrition.[15,16,17,18] Stigma, lack of partner/family support, or concerns to be seen while seeking care are a common impediment for patients to continue in care.[4,19,20] Additionally, other themes related with the individual, such as financial problems, perception of wellness, drug adverse effects, or poor health have been described.[4,20] Lastly, healthcare systems with low coverage, overburdened staff, administrative problems, and/or inefficient delivery of services contribute to patient attrition.[4]

We evaluated the outcomes of a cohort of people living with HIV (PLWHIV) in southern Mozambique who were LTFU at different stages of the HIV-cascade, through a home-based tracing study, and to assess the impact of this visit on reengagement. Moreover, we identified self-reported barriers for continuation in care among LTFU patients.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study setting and participants

The current tracing study was conducted between June 2015 and July 2016 in the Manhiça District Hospital (MDH) located in Manhiça District, a semi-rural area in Maputo province, southern Mozambique. Since 1996, the Centro de Investigação em Saúde de Manhiça (CISM) runs a continuous health and demographic surveillance system (HDSS) for vital events, including births, deaths, and migrations. In 2015, at the time of the study, the district population was nearly 174,000[21] and in 2012 the estimated community HIV prevalence was 39.7% among adult population.[22] HIV services are offered free of charge in all healthcare facilities. The CD4 threshold for ART initiation at the time of the study, per national guidelines, was ≤350 and ≤500 cells/mm3 after 2016.[23] Routine patient-level HIV clinical data were recorded in a Ministry of Health–managed electronic patient tracking system (ePTS), which allows monitoring of HIV patients registered at the facility, quality of care, and retention in care

The current study was embedded in a larger prospective observational cohort which consecutively enrolled patients with a new HIV diagnosis between May 2014 and June 2015 from 3 different testing modalities: voluntary counseling and testing, provider-initiated counseling and testing, and home-based testing.[23] Inclusion criteria for the cohort were being ≥18 years of age, residing in the MDH catchment area, and receiving a first HIV-positive result. Exclusion criteria included co-infection with tuberculosis, pregnancy at the time of diagnosis, or having an HIV-negative test result in the previous 3 months.[23] All participants with a new HIV diagnosis were referred to the MDH for enrollment in HIV care. The study procedures did not influence linkage to care beyond testing and facility-based guidance to the MDH reception. Further details regarding the cohort study procedures can be found elsewhere.[23,24] The current tracing study included patients in the cohort who were identified as LTFU through the ePTS system 12 months after initial diagnosis.

2.2. Study procedures and data collection

LTFU participants identified through the ePTS were crosschecked with their paper-based chart in real time to identify misclassification due to missing data or incorrect data entry. The list of LTFU patients was then merged with the HDSS database to identify individuals who migrated or had died and to locate the homes of patients LTFU. Patients were considered as primary-LTFU if they had never enrolled in care and secondary-LTFU if they had not had a clinical visit in the previous 180 days, according to a proposed conservative universal definition of LTFU in HIV treatment programs, which corresponds to being at least 90 days late for a clinical visit.[25,26] At the time of study implementation, adult patients LTFU were not routinely traced in the district.

Two experienced counselors located each patient's house and performed a home visit. If the person was not at home, the counselor returned a maximum of 3 times to locate the person. The main objective of the survey for the home visit was to confirm LTFU and the step of the cascade at which the patient was lost. Additionally, a multi-choice, open text questionnaire was administered to determine self-reported reasons for LTFU.

The steps of the cascade included enrollment in care, clinical consultation, clinical or laboratory staging, ART initiation, and retention in care. All patients were asked to show their HIV clinical card provided by MDH, and patients receiving ART were asked to show their pills for the current month. Patients who denied having a previous HIV test or HIV-positive result were offered the opportunity to be retested (HIV testing and counseling were also offered to all household members). For HIV-positive patients who were LTFU at MDH or at any other ART clinic, the interviewer conducted a counseling session to reengage the patients in care in the health facility of their choice.

2.3. Quantitative methods and analysis

During the home-based tracing visit, information regarding each participant was recorded digitally in Open Data Kit software 1.4 and uploaded into a database in REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture).[27,28] The information from the home-based tracing visit was merged with data from the ePTS, HDSS, and cohort database to obtain relevant variables. Data collected at the home visit allowed identification of silent transfers, system failures, and errors in the ePTS database. To evaluate the potential reengagement of patients, we abstracted data from ePTS on clinical consultations occurring after the visit from the administrative censoring until January 27, 2017.

STATA 14.1 was used for descriptive and inferential statistical analysis (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). For those participants who were not interviewed at 12 months post-diagnosis, their reengagement in care was estimated over the same time period as those interviewed (i.e., 12–15 months post-diagnosis). Descriptive analysis of the categorical variables of the study population was performed, and the Chi-squares test was used to assess significant differences between the different groups. Continuous variables were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), and the P-value corresponded to the Kruskal–Wallis test. Univariate and multivariate survival analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model was conducted to determine the association between the explanatory variables and the study outcome, reengagement in care, for those participants who received the intervention. Significant variables (P < 0.2) in univariate analysis or that were considered potential confounders (age and sex) were retained in the multivariate model.

2.4. Qualitative methods and analysis

Questions exploring barriers to linkage and retention were digitally recorded in Portuguese during the home visit. These semi-qualitative questions had 2 components: a multi-choice predefined codebook[15,16,18,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] and an open text field to complete the response if necessary. All open narratives were coded and tabulated along with the other answers into a matrix format using Microsoft Excel. This matrix was pre-designed to classify the barriers of each step in the HIV care cascade, and new codes were added as they emerged from the surveys. The barriers were grouped into 3 main themes: social climate, individual-level determinants, and health system determinants. Two researchers performed the analysis, and disagreements were discussed with another researcher in the HIV department.

2.5. Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Mozambican National Bioethics Committee and by the Institutional Review Boards at the Barcelona Institute of Global Health and CISM. The study was also reviewed in accordance with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) human research protection procedures and was determined to be research, but CDC investigators did not interact with human subjects or have access to identifiable data or specimens for research purposes. All participants provided written informed consent.

3. Results

3.1. Study profile

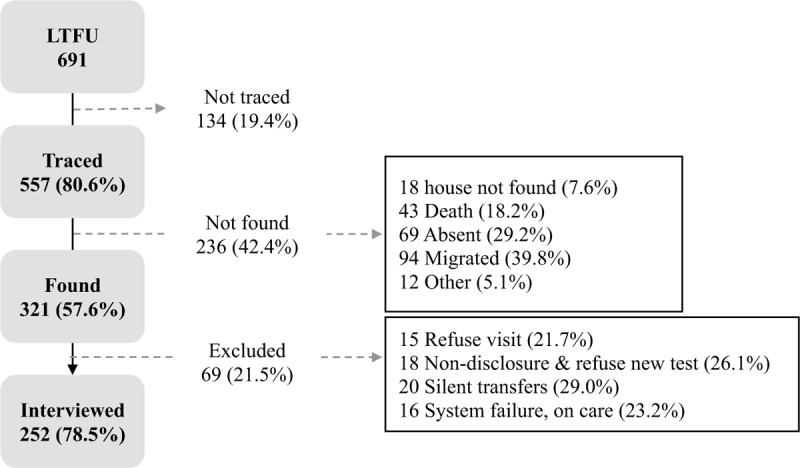

Among the 1122 Tesfam participants, 691 were LTFU (61.6%), and, of those, 557 (80.6%) were traced (Fig. 1). Non-traced participants were those not listed, or misidentified, as LTFU during the real-time generation of lists (N = 134, 19.4%). A total of 236 (42.4%) participants were not found after 3 attempts for the following reasons: 43 (18.2%) were deceased, 69 (29.2%) were absent, 94 (39.8%) had migrated, 18 (7.6%) houses were not found, and 12 (5.1%) were not found for other reasons. An additional 69 participants were excluded: 15 (21.7%) refused to participate, 18 (26.1%) did not disclose their previous HIV status to the counselor and refused to be tested, and 36 (52.2%) were misclassified as LTFU. Among these 36, 20 (55.6%) were silent transfers, and 16 (44.4%) had been misclassified as LTFU by a system failure and showed their hospital identification card at the home visit demonstrating that they were in care. Thus, 11.3% (36 of the 321 found) were misclassified as LTFU and 252 of the 557 traced participants (45.2%) were interviewed.

Figure 1.

Study profile for patients of the Tesfam cohort in Mozambique who were lost to follow-up and who received a home-based tracing visit. Percentages are calculated over the previous step.

3.2. Baseline characteristics of the study populations

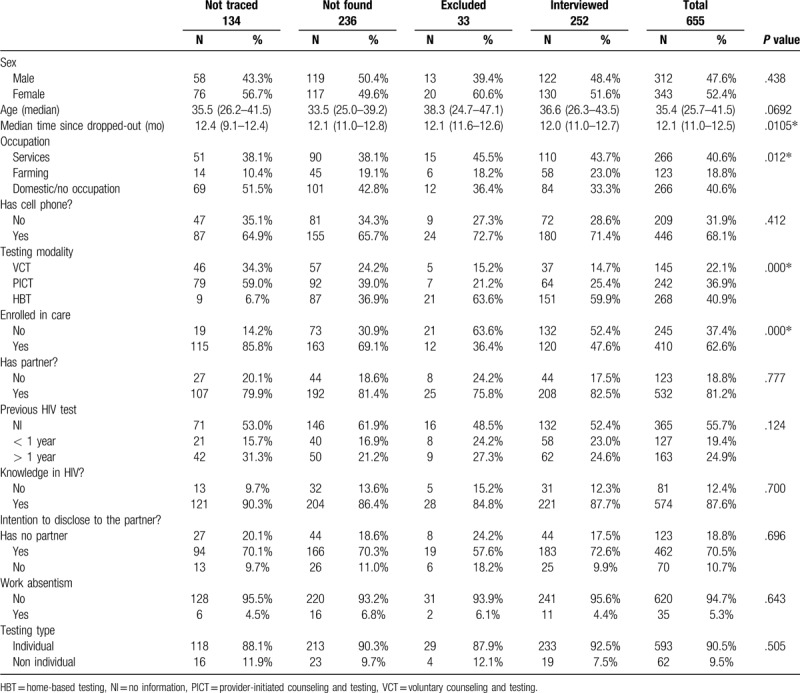

We compared the baseline population characteristics of the 655 participants LTFU who were either not traced (N = 134), not found (N = 236), excluded due to refusal and not disclosing their status to counselors (N = 33), and those who were interviewed (N = 252; Table 1). Overall 47.6% were men, and the median age at the time of HIV diagnosis was 35.4 years (IQR, 25.7–41.5).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of HIV patients lost to follow-up in rural southern Mozambique according to study population group.

Baseline characteristics did not differ between groups except for testing modality, occupation, and type of LTFU. Overall, more than one-third (245 [37.4%]) were primary-LTFU and 410 (63.6%) were secondary-LTFU. The percentage of primary-LTFU was higher among those excluded from the interview (63.6%) and lowest among those not traced (14.2%).

Among those interviewed, 137 (54.4%) had not enrolled at the health facility and thus were considered primary-LTFU. Nineteen (7.5%) interviewed patients who did enroll in care did not attend the first clinical consultation. Nineteen (7.5%) patients who met ART eligibility criteria never started treatment. Lastly, 16 (6.3%) patients out of the 252 visited were receiving ART and missed a pharmacy pickup and were thus LTFU post-ART initiation (Supplemental Content, Figure S1).

3.3. Reengagement in care

Among interviewed participants, 79 (31.3%) reengaged in care within 3 months of the 12-month home visit, with a median time to reengagement in care of 5 days (IQR, 2–8) for those who had not enrolled in care after HIV diagnosis (primary LTFU) and 8 days (IQR, 3–23) for those who had enrolled in care. For each additional month between LTFU and home visit, 5% less individuals reengaged in care. For those not interviewed, reengagement in care 12 to 15 months post-diagnosis was 6.0%, 4.2%, and 0.0% among participants not traced, not found, and refusals, respectively.

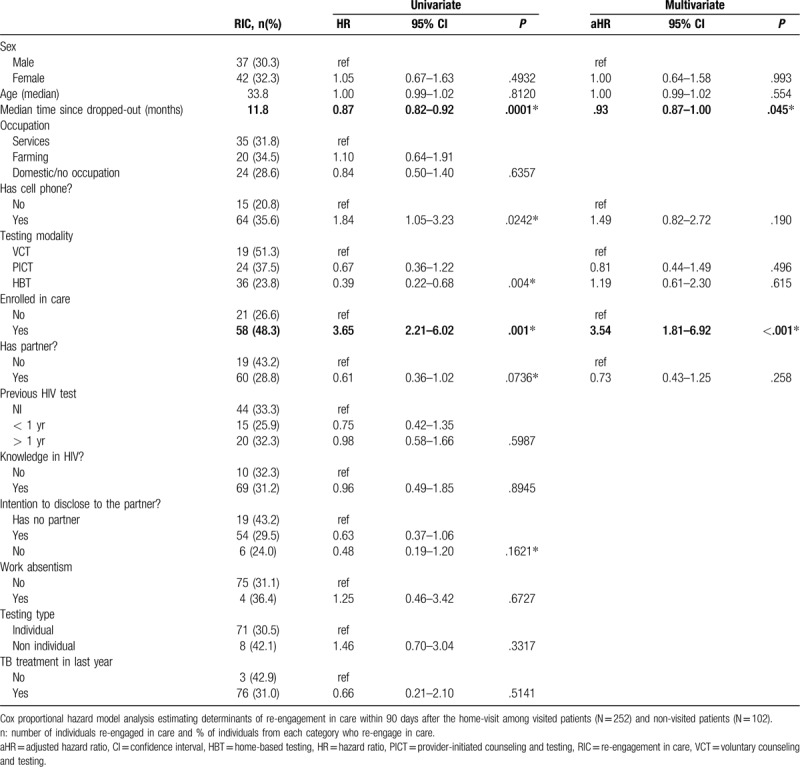

Table 2 shows the results of the univariate and multivariate analysis of potential factors associated with reengagement in care among participants who were interviewed. In the univariate model, having a cellphone, having received home-based testing, being secondary-LTFU, and being single were associated with increased likelihood of reengagement in care, and the delay between LTFU and the home visit was associated with decreased likelihood of reengagement in care. However, in multivariate analysis, only being secondary-LTFU and delay between LTFU and the home visit remained significantly associated with reengagement in care, with adjusted hazard ratios of 3.54 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.81–6.92; P < 0.001) and 0.93 (95% CI: 0.87–1.00; P = 0.045), respectively.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with re-engagement in care (RIC) among HIV patients lost to follow-up in rural southern Mozambique.

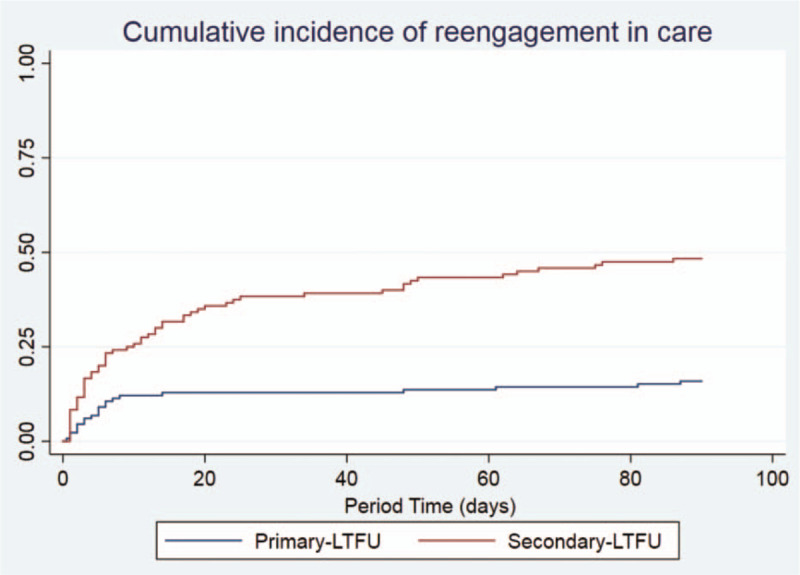

More than half of the patients who reengaged in care (47/79, 59.5%) did so within the first 10 days after the home visit. Figure 2 displays the survival curve estimates of cumulative incidence of reengagement in care over 90 days after the visit for primary-LTFU vs secondary-LTFU patients.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of reengagement in care after home visit and interview among participants who had (secondary-loss to follow-up) and had not previously enrolled in HIV care (primary-loss to follow-up) in rural southern Mozambique. Unadjusted cumulative proportion of reengagement in care after home visit over time.

3.4. Patient self-reported barriers to care

During the first year after HIV diagnosis, individual determinants and health system factors were the most frequent barriers that influenced the continuation in HIV care. Several crosscutting barriers emerged during the analysis of individual responses but varied between early and later steps of the cascade. Denial of HIV-positive status or lack of trust in the result was one of the most frequent barriers in those who did not enroll in care and in those who enrolled and did not have a first clinic visit (15% and 10%, respectively) compared to later stages of the cascade (5%). Another frequently reported barrier was loss of the hospital referral slip that patients receive the day of HIV diagnosis, which allows them to enroll in care. Once enrolled in care, the most common barriers were loss of the hospital identification card, fear of being badly treated by health personnel, and work responsibilities. Other frequent challenges were the distance to the health facility and long waiting times.

Among primary-LTFU participants, individual determinants accounted for 40% of all barriers and included self-perception of being in good health and thus not requiring treatment. Several participants stated that they had been tested for HIV multiple times with varying outcomes, which led them to no longer believe any result or to be confused about their serostatus:

“I was tested when I wanted to be circumcised, and they said that I was negative, so they did it. Two weeks after, at home, I tested again, and the result was positive. So I went to the hospital to confirm, and was negative.” [Man, 21]

Regarding a discouraging social climate, several patients did not disclose being HIV positive and did not acknowledge previous HIV testing.

Secondary-LTFU reported that in subsequent steps of the cascade, reasons for dropping out after linkage were mainly associated with the HIV-clinic care flow. Several participants reported fear of being scolded by health personnel if they had lost the hospital card or missed 1 clinical appointment and cited long waiting times at the clinic.

4. Discussion and conclusions

Among HIV-positive adults LTFU in a rural district of Mozambique who were traced 12 months after diagnosis, less than half could be located and interviewed about their care. Among those interviewed, one-third subsequently reengaged in care and 11.3% were misclassified as LTFU. Those LTFU patients who had enrolled in care at a health facility after HIV diagnosis (secondary-LTFU) were 4 times more likely to reengage in care than those who had not previously enrolled at any health facility after their HIV diagnosis. Moreover, close to 60% of reengaged patients did so within the first 10 days after the home visit. Reason for disengagement varied by type of LTFU. For primary-LTFU patients, the main self-reported barriers to care were the denial of HIV status or lack of trust in the HIV diagnosis and the perception of being in good health, whereas for secondary-LTFU, the main barriers were the fear of being badly treated by health personnel and workflow constraints in the health facility.

Examining LTFU and designing interventions to promote reengagement in care is hampered by the accuracy of distinguishing true LTFU from other outcomes such as transfer to another facility (silent transfers), mobility, and death outside of the health facility. Of 691 adult patients identified as LTFU 12 months after HIV diagnosis, we determined that 30% (112) had migrated or were repeatedly absent from the household, and 18% (43) had died. In San Francisco, Christopoulos et al found that surveillance data increased the proportion of patients misclassified as LTFU by 4-fold as compared to a tracing study.[42] Misclassification of non-LTFU patients as LTFU leads to an overestimation of LTFU and an underestimation of retention which can result in poor use of resources in reengagement in care.

Additionally, errors in ePTS can lead to underestimating and/or overestimating LTFU. In our cohort, over 50%, of those classified as LTFU by the health facility were deceased or had migrated and among those found for a visit, 11.3% were misclassified as LTFU when they were silent transfers or system failures. We also identified true LTFU patients who had not been detected by the ePTS in real time and thus had not received a home visit. Most SSA countries enter information from paper charts into ePTS rather than direct entry during clinical visits, which can result in entry errors and incomplete information compounding misclassification errors. This incites caution in LTFU estimates and suggests that true LTFU may be nearly half of estimated LTFU without ascertainment of outcome.

To ensure efficiency in reengaging traced patients, different tracing methods are likely to be required according to timing and stage of the cascade at which the patient is LTFU. In our population, individuals who had already enrolled in care were 4 times more likely to reengage in care after a home visit than those who never enrolled in care. For each additional month between LTFU and home visit, 7% fewer individuals reengaged in care, suggesting that the sooner individuals are traced, the more likely they are to resume care. The effect is small but cumulative. Indeed, a meta-analysis of individual patient data suggested that the longer the delay between LTFU and tracing, the less likely the patient is to reengage in care.[43]

Home visits may be more effective than other methods of tracing in SSA. A meta-analysis of 32 studies in SSA showed that LTFU patients who received a home visit were 5 to 9 times more likely to reengage in care than those who had received a phone call.[5] A home visit might be necessary for individuals who are at an early phase of their HIV care, whereas a telephone call may be sufficient for those who remained on ART for several years before disengaging or who have recently disengaged. In our cohort, more than half of patients who reengaged in care did so within the first 10 days after the home visit. This is in line with results published from 14 health clinics in Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania, which showed that the increased rate of reengagement in care after a home visit decreased to the rate without a visit with a half-life of 7 days after the visit.[44]

Self-reported reasons for LTFU can also be considered when designing approaches to reengage patients in care. In our population, a common reason for not enrolling in care was denial or distrust of the diagnosis, which can lead to individuals returning for repeat testing.[24] Disbelief of the diagnosis is an important hurdle to overcome in ART care.[45,46,47] These findings suggest the need for counselling tailored to acceptance of the lifelong nature of HIV infection as well as explaining discrepant test results. Another reason given by the Mozambican patients for disengagement was fear of being scolded by health facility staff. A qualitative study in Tanzania revealed that poor treatment at the clinic made patients feel guilt and shame at their disengagement[48] as did a study in Manhiça Mozambique.[49] Although patients should be made aware of the dangers of disengagement, flexible fast-track reengagement polices could improve reengagement in care. A study in east Africa showed differences in levels of reengagement in care between primary, secondary, and tertiary care facilities and suggested that the category of healthcare facilities may be a proxy for other factors, including appropriate staffing, available resources, and services provided.[50]

The lack of information on patterns of patient disengagement and factors associated with return to HIV care makes developing tailored reengagement strategies difficult. One study in 6 large health facilities in the United States found that a past-year missed visit was a moderate predictor of future missed visits[51] however, specific predictors for SSA settings and for different stages of the HIV care cascade are unknown. Further understanding may help tailor retention and reengagement in care strategies.

Our study has several limitations. Over half of the LTFU patients in our cohort could not be reached or interviewed primarily due to absence or migration, which limits the generalizability of our findings but reflects the realities faced by any tracing program. The lack of a comparison group that did not receive home visits limits our interpretation of causality of the home visit on reengagement in care. Nevertheless, since most of the individuals who reengaged in care did so within 10 days of the visit, we can infer that their reengagement was associated with the visit.[44] We cannot, however, make inferences about the causal relationship of the home visit and reengagement in care at later times. Secondly, due to the lack of information, potential clinical factors such as CD4 or WHO stage, that could be associated with re-engagement in care, were not included in the analysis. Lastly, as this study was embedded in a larger cohort, which aimed to measure linkage and retention in care at twelve months, long-term retention among this cohort was not measured and as such, no subsequent disengagements were measured. Although previous studies in the same region suggest that close to 20% of patients in long-term care self-reported sporadic interruptions along their continuum.[49] This “cascade churn”, understood as the mobility into and out of the cascade of HIV care, has been described worldwide as one of the fundamental components that should be measured to monitor the success of the Treat All strategy.[52,53,54,55,56]

The accelerated scale-up of universal test and treat seeks to ensure that 33 million PLWHIV initiate ART, and that 90% of those reach viral suppression by 2020.[57] However, disengagement from HIV care presents a threat to epidemic control and the effectiveness of HIV treatment programs. Alongside the 90-90-90, a long-term retention target such as ensuring that 90% with viral suppression are retained 5 years after ART initiation, may need to be established in order to galvanize stakeholders and programs to combat the dangers of poor ascertainment of LTFU and poorly enforced guidelines for reengagement in care. Thus, in the era of differentiated care, progressive integration of strategies for differentiated reengagement in care will be needed, taking into account the level of health facility, type of patient, acceptance of HIV, type of LTFU, and cascade stage of ART care.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Ministry of Health of Mozambique, our research team, collaborators, and especially all communities and participants involved. We want to especially acknowledge Elisabeth Salvo for her contributions to editing the manuscript.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Denise Naniche, Elisa López-Varela.

Study Design: Denise Naniche, Elisa López-Varela, Laura Fuente-Soro.

Data curation: Laura Fuente-Soro, Elisa López-Varela, Orvalho Augusto, Charfudin Sacoor, Ariel Nhacolo, Charity Alfredo, Edson Luis Bernardo.

Formal analysis: Laura Fuente-Soro, Elisa López-Varela, Denise Naniche, Paula Ruiz-Castillo.

Project administration: Laura Fuente-Soro.

Writing– original draft: Laura Fuente-Soro, Elisa López-Varela.

Writing – review & editing: All authors.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ART = antiretroviral therapy, CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CI = confidence interval, CISM = Centro de Investigação em Saúde de Manhiça, ePTS = electronic patient tracking system, HDSS = Health Demographic Surveillance System, HIV = human immunodeficiency virus, IQR = interquartile ranges, LTFU = lost to follow-up, MDH = Manhiça District Hospital, PLWHIV = people living with HIV, SSA = sub-Saharan Africa.

How to cite this article: Fuente-Soro L, López-Varela E, Augusto O, Bernardo EL, Sacoor C, Nhacolo A, Ruiz-Castillo P, Alfredo C, Karajeanes E, Vaz P, Naniche D. Loss to follow-up and opportunities for reengagement in HIV care in rural Mozambique: a prospective cohort study. Medicine. 2020;99:20(e20236).

LF-S and EL-V contributed equally to this work.

This study was made possible with support from the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under the terms of CoAg GH000479 (Scaling-up HIV counseling & testing services in a rural population by strengthening the health demographic surveillance system in Manhiça, Mozambique).

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding agencies.

ISGlobal is a member of the CERCA Programme, Generalitat de Catalunya.

ELV is supported by Rio Hortega doctoral fellowship, Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

CISM is supported by the Government of Mozambique and the Spanish Agency for International Development (AECID).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

References

- [1].Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365:493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tanser F, Bärnighausen T, Grapsa E, Zaidi J, Newell M-L-L. High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Science 2013;339:966–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Brinkhof MMWGMW, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Egger M, et al. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2009;4:e5790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fox MP, Rosen S. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to three years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007-2009: systematic review. Trop Med Int Heal 2010;15: Suppl. 1: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zürcher K, Mooser A, Anderegg N, et al. Outcomes of HIV-positive patients lost to follow-up in african treatment programmes. XXXX 2017;22:375–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].República de Moçambique Conselho Nacional de Combate Ao SIDA Resposta Global À SIDA Relatório Do Progresso, 2016 MOÇAMBIQUE; 2016. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/MOZ_narrative_report_2016.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2018.

- [7].Kranzer K, Govindasamy D, Ford N, et al. Quantifying and addressing losses along the continuum of care for people living with HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc 2012;15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kranzer K, Ford N. Unstructured treatment interruption of antiretroviral therapy in clinical practice: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health 2011;16:1297–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Buchacz K, Chen MJ, Parisi MK, et al. Using HIV surveillance registry data to re-link persons to care: the RSVP project in San Francisco. PLoS One 2015;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Magnus M, Herwehe J, Gruber D, et al. Improved HIV-related outcomes associated with implementation of a novel public health information exchange. Int J Med Inform 2012;81(10):e30–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Udeagu CCN, Webster TR, Bocour A, Michel P, Shepard CW. Lost or just not following up: public health effort to re-engage HIV-infected persons lost to follow-up into HIV medical care. AIDS 2013;27:2271–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tweya H, Gareta D, Chagwera F, et al. Early active follow-up of patients on antiretroviral therapy (ART) who are lost to follow-up: the “Back-to-Care” project in Lilongwe, Malawi. Trop Med Int Heal 2010;15: SUPPL. 1: 82–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Colasanti J, Stahl N, Farber EW, del Rio C, Armstrong WS. An exploratory study to assess individual and structural level barriers associated with poor retention and re-engagement in care among persons living with HIV/AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;74:S113–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fernández-Luis S, Fuente-Soro L, Augusto O, et al. Reengagement of HIV-infected children lost to follow-up after active mobile phone tracing in a rural area of Mozambique. J Trop Pediatr 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Knight LC, Van Rooyen H, Humphries H, Barnabas RVV, Celum C. Empowering patients to link to care and treatment: qualitative findings about the role of a home-based HIV counselling, testing and linkage intervention in South Africa. AIDS Care 2015;1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hladik W, Benech I, Bateganya M, Hakim AJ. The utility of population-based surveys to describe the continuum of HIV services for key and general populations. Int J STD AIDS 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Camlin CS, Neilands TB, Odeny TA, et al. Patient-reported factors associated with reengagement among HIV-infected patients disengaged from care in East Africa. AIDS 2016;30:495–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tomori C, Kennedy CE, Brahmbhatt H, et al. Barriers and facilitators of retention in HIV care and treatment services in Iringa, Tanzania: the importance of socioeconomic and sociocultural factors. AIDS Care 2014;26:907–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Klopper C, Stellenberg E, van der Merwe A. Stigma and HIV disclosure in the Cape Metropolitan area, South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res 2014;13:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Brinkhof MW, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Egger M. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2009;4:e5790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sacoor C, Nhacolo A, Nhalungo D, et al. Profile: Manhica Health Research Centre (Manhica HDSS). Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:1309–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].González R, Munguambe K, Aponte J, et al. High HIV prevalence in a southern semi-rural area of Mozambique: a community-based survey. HIV Med 2012;13:581–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lopez-Varela E, Fuente-Soro L, Augusto OJ, et al. Continuum of HIV care in rural Mozambique: the implications of HIV testing modality on linkage and retention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;78:527–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fuente-Soro L, Lopez-Varela E, Augusto O, et al. Monitoring progress towards the first UNAIDS target: understanding the impact of people living with HIV who re-test during HIV-testing campaigns in rural Mozambique. J Int AIDS Soc 2018;21:e25095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chi BH, Yiannoutsos CT, Westfall AO, et al. Universal definition of loss to follow-up in HIV treatment programs: a statistical analysis of 111 facilities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ministerio da Saude. Republica de Moçambique. Guia de Tratamento Antiretroviral e Infecçoes Oportunistas no Adulto, Adolescente, Grávida e Criança. 2013.

- [27].Carl Hartung, Yaw Anokwa, Waylon Brunette, Adam Lerer, Clint Tseng GB. Open data kit: tools to build information services for developing regions. 2010. http://www.gg.rhul.ac.uk/ict4d/ictd2010/papers/ICTD2010 Hartung et al.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2017.

- [28].Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2008;42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].da Silva M, Blevins M, Wester Cw W, et al. Patient loss to follow-up before antiretroviral therapy initiation in rural mozambique. AIDS Behav 2015;19:666–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Govindasamy D, Ford N, Kranzer K. Risk factors, barriers and facilitators for linkage to antiretroviral therapy care. AIDS 2012;26:2059–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bezabhe WM, Chalmers L, Bereznicki LR, Peterson GM, Bimirew MA, Kassie DM. Barriers and facilitators of adherence to antiretroviral drug therapy and retention in care among adult HIV-positive patients: a qualitative study from Ethiopia. PLoS One 2014;9:e97353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].De Schacht C, Lucas C, Mboa C, et al. Access to HIV prevention and care for HIV-exposed and HIV-infected children: a qualitative study in rural and urban Mozambique. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Holtzman CW, Shea JA, Glanz K, et al. Mapping patient-identified barriers and facilitators to retention in HIV care and antiretroviral therapy adherence to Andersen's Behavioral Model. AIDS Care 2015;27:817–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Tabatabai J, Namakhoma I, Tweya H, Phiri S, Schnitzler P, Neuhann F. Understanding reasons for treatment interruption amongst patients on antiretroviral therapy–a qualitative study at the Lighthouse Clinic, Lilongwe, Malawi. Glob Health Action 2014;7:24795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].hIarlaithe MO, Grede N, de Pee S, Bloem M. Economic and social factors are some of the most common barriers preventing women from accessing maternal and newborn child health (MNCH) and prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services: a literature review. AIDS Behav 2014;18: Suppl.5: 516–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Phelps BR, Ahmed S, Amzel A, et al. Linkage, initiation and retention of children in the antiretroviral therapy cascade: an overview. AIDS 2013;27: Suppl. 2: S207–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bogart Lm M, Chetty S, Giddy J, et al. Barriers to care among people living with HIV in South Africa: contrasts between patient and healthcare provider perspectives. AIDS Care 2013;25:843–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Miller CM, Ketlhapile M, Rybasack-Smith H, Rosen S. Why are antiretroviral treatment patients lost to follow-up? A qualitative study from South Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15(S(uppl. 1)):48–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Govindasamy D, Meghij J, Kebede Negussi E, Clare Baggaley R, Ford N, Kranzer K. Interventions to improve or facilitate linkage to or retention in pre-ART (HIV) care and initiation of ART in low- and middle-income settings–a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc 2014;17:19032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pecoraro A, Mimiaga MJ, O’Cleirigh C, et al. Lost-to-care and engaged-in-care HIV patients in Leningrad Oblast, Russian Federation: barriers and facilitators to medical visit retention. AIDS Care 2014;26:1249–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lifson A.R., Demissie W., Tadesse A., et al. Barriers to retention in care as perceived by persons living with HIV in rural Ethiopia: focus group results and recommended strategies. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 12(1):32-38. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [42].Christopoulos KA, Scheer S, Steward WT, et al. Examining clinic-based and public health approaches to ascertainment of HIV care status. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;69:S56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chammartin F, Zürcher K, Keiser O, et al. Outcomes of patients lost to follow-up in African antiretroviral therapy programs: individual patient data meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2018;67:1643–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bershetyn A, Odeny TA, Lyamuya R, et al. The causal effect of tracing by peer health workers on return to clinic among patients who were lost to follow-up from antiretroviral therapy in Eastern Africa: a “natural experiment” arising from surveillance of lost patients. Clin Infect Dis 2017;64:1547–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Horter S, Thabede Z, Dlamini V, et al. Life is so easy on ART, once you accept it”: acceptance, denial and linkage to HIV care in Shiselweni, Swaziland. Soc Sci Med 2017;176:52–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Treves-Kagan S, Steward WT, Ntswane L, et al. Why increasing availability of ART is not enough: a rapid, community-based study on how HIV-related stigma impacts engagement to care in rural South Africa. BMC Public Health 2015;16:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Geng EH, et al. Toward an Understanding of disengagement from HIV treatment and care in sub-Saharan Africa: a qualitative study. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Layer EhH, Brahmbhatt H, Beckham SwW, et al. I pray that they accept me without scolding:” experiences with disengagement and re-engagement in HIV care and treatment services in Tanzania. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2014;28:483–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Fuente-Soro L, Iniesta C, López-Varela E, et al. Tipping the balance towards long-term retention in the HIV care cascade: a mixed methods study in southern Mozambique. PLoS One 2019;14:e0222028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Rachlis B, Bakoyannis G, Easterbrook P, et al. Facility-level factors influencing retention of patients in HIV care in East Africa. PLoS One 2016;11:e0159994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Pence BW, Bengtson AM, Boswell S, et al. Who will show? Predicting missed visits among patients in routine HIV primary care in the United States. AIDS Behav 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Nsanzimana S, Binagwaho A, Kanters S, et al. Churning in and out of HIV care. XXXXX 2014;1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Nosyk B, Lourenço L, Min E, et al. Characterizing retention in HAART as a recurrent event process: insights into “cascade churn”. AIDS 2015;29:1681–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Krentz HB, Gill MJ. The effect of churn on “community viral load” in a well-defined regional population. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;64:190–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Gill MJ, Krentz HB. Unappreciated epidemiology: the churn effect in a regional HIV care programme. Int J STD AIDS 2009;20:540–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Mills EJ, Funk A, Kanters S, et al. Long-term health care interruptions among HIV-positive patients in Uganda. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;63(1):e23–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].UNAIDS. 90-90-90. An Ambitious Treatment Target to Help End the AIDS Epidemic; 2014. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en_0.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.