Key Points

Question

Is hidradenitis suppurativa associated with increased risks of overall and specific cancers in patients with this condition?

Findings

In a population-based study, 22 468 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa in the Republic of Korea had increased risks of overall cancer compared with 179 734 individuals without hidradenitis suppurativa. In addition, the risks of specific cancers, such as Hodgkin lymphoma and oral cavity and pharyngeal, central nervous system, nonmelanoma skin, prostate, and colorectal cancer, were increased.

Meaning

More intense cancer surveillance may be warranted in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa.

Abstract

Importance

Large population-based studies investigating the risks of overall and specific cancers among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) are limited.

Objective

To assess the overall and specific cancer risks in patients with HS compared with the risks in patients without HS in the Republic of Korea.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A nationwide population-based cohort study, using the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database was conducted over a 2-year period from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2008. Individuals in the control group who were never diagnosed with HS or cancer during the washout period were randomly extracted and matched by age, sex, index year, and insurance type at a case-control ratio of 1:8, and patients with newly diagnosed HS between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2017, were included. Follow-up data on incident cancer from January 1, 2009, to December 31, 2018, were included.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The overall and specific cancer incidence rates were calculated per 100 000 person-years in patients with HS and in the matched control cohort. The risk for cancers was assessed by multivariable Cox regression models in patients with HS compared with the matched control cohort.

Results

In total, 22 468 patients with HS and 179 734 matched controls were included in the study. The mean (SD) age was 33.63 (17.61) years and 63.7% of the participants in both groups were male. The adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of overall cancer in patients with HS was 1.28 (95% CI, 1.15-1.42). Patients with HS had significantly higher risk for Hodgkin lymphoma (aHR, 5.08; 95% CI, 1.21-21.36), oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer (aHR, 3.10; 95% CI, 1.60-6.02), central nervous system cancer (aHR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.22-4.70), nonmelanoma skin cancer (HR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.12-3.79), prostate cancer (aHR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.30-3.24), and colorectal cancer (aHR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.09-1.93).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, HS appeared to be associated with a significantly increased risk of overall cancer as well as several specific cancers.

This population-based study examines the prevalence of cancer in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa.

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease, chiefly affecting apocrine gland–bearing skin.1 Hidradenitis suppurativa is one of the most debilitating dermatologic conditions, and the association between HS and reductions in quality of life and psychosocial well-being has been widely reported.2,3,4,5 Hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with severe comorbidities, which can lead to substantially reduced life expectancy.6,7,8,9,10 While the pathogenesis of HS is unclear, several inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interferon-γ, interleukin (IL)-10, IL-12, IL-17, IL-23, and IL-32, as well as antimicrobial peptides LL-37, psoriasin, and β-defensins 2 and 3, may be factors in the development of the disease.11,12,13,14 Specific genetic and environmental factors seem to contribute to the development and phenotype of HS.11 The aberrant immune response and chronic inflammation in HS and genetic and environmental factors associated with the disease may all be factors in the development of cancer. The connection between HS and cancer has been suggested: a study of 2119 Swedish patients found that HS was associated with an approximate 50% increase in the relative risk of cancer.15 Cases of nonmelanoma skin cancer complicating HS have also been reported.16,17 Vulvar, perianal, and perineal cancer can develop in patients with HS.18 An association between HS and lymphoma has also been reported recently.19 However, there are limited large, population-based epidemiologic studies regarding the risks of overall and specific cancers among patients with HS. Thus, we conducted a nationwide, population-based study to determine the overall and specific cancer risks in patients with HS compared with the risks in patients without HS in the Republic of Korea.

Methods

Data Source

The Korean National Health Insurance system, mandated by law, covers approximately 97% of the 50 million people in the Republic of Korea. The Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database comprises a large amount of data on all National Health Insurance claims, including patient demographic characteristics, diagnoses using International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes, and prescribed drugs and procedures.20 The database also provides a rare incurable disease registry for diseases such as cancer. The rare incurable disease system is reliable because diagnoses are certified by physicians using designated criteria, which include histopathologic examinations before the disease can be registered in the system. Registered patients can have more than 90% of their medical expenses covered.

The institutional review board of Asan Medical Center approved this study with waiver of informed consent, and it was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.21 Data are deidentified.

Study Population

We defined patients with HS as those who had at least 2 documented physician contacts within a year between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2017, at which HS (ICD-10 code L729) was the principal diagnosis as previously described to minimize misclassification.9 In Korea, HS is primarily diagnosed by dermatologists when recurrent painful or suppurating papules or nodules are identified in typical apocrine gland–bearing skin regions, such as axillary, genitofemoral, perineal, and gluteal areas.9 Patients who had HS or cancer diagnosed during a 2-year period from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2008, were excluded. Controls who were never diagnosed with HS or cancer during that period were randomly extracted and matched by age (within a 5-year range), sex, index year (the year of the first HS diagnosis), and insurance type at a case-control ratio of 1:8. Follow-up data for incident cancer from 2009 to 2018 were included for these retrospective cohorts. Ascertainment of cancer diagnosis was achieved from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database using ICD-10 cancer codes (eTable 1 in the Supplement) and rare incurable disease registration code (V193) simultaneously to minimize misclassification.

Comorbidities of interest in the study included hypertension (ICD-10 codes I10-I13 and I15), type 1 diabetes (ICD-10 code E10), type 2 diabetes (ICD-10 codes E11-E14), dyslipidemia (ICD-10 code E78), alcoholic liver disease (ICD-10 code K70), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ICD-10 code J44), liver cirrhosis (ICD-10 code K74), chronic kidney disease (ICD-10 code N18), and heart failure (ICD-10 code I50). Patients were defined as having a comorbidity when they had at least 10 physician visits with a corresponding diagnostic code within the study period and when the first visit was made before the cancer diagnosis.

Patients with HS were classified as having mild HS if they had not received any surgical or systemic anti-TNF-α treatment. Hidradenitis suppurativa was categorized as moderate to severe if the patients had received surgical treatment (excision, marsupialization, or wide excision) and/or systemic anti-TNF-α therapy.

Statistical Analysis

The t test was used to compare continuous variables and the χ2 test was used for binary and categorical variables. The overall and specific cancer incidence rates were calculated per 100 000 person-years. We estimated the 95% CIs of the prevalence and incidence rates by applying Poisson distribution. The risk for cancers was assessed by multivariable Cox regression models. Results are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs. All of the statistical tests were 2- tailed. P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide software, version 6.1 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

In total, 22 468 patients with HS and 179 734 matched controls were included in the study (eFigure in the Supplement). Baseline characteristics of each group are described in Table 1. The mean (SD) age was 33.63 (17.61) years and 63.7% of the participants in both groups were male. Comorbidities were found to be more common in patients with HS than in patients in the control cohort, such as hypertension (2930 [13.0%] vs 20 629 [11.5%], P < .001), type 1 diabetes (97 [0.4%] vs 482 [0.3%], P < .001), type 2 diabetes (1785 [7.9%] vs 9635 [5.4%], P < .001), dyslipidemia (2849 [12.7%] vs 16 212 [9.0%], P < .001), alcoholic liver disease (116 [0.5%] vs 712 [0.4%], P = .008), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (114 [0.5%] vs 729 [0.4%], P = .03), chronic kidney disease (140 [0.6%] vs 680 [0.4%], P < .001), and heart failure (140 [0.6%] vs 889 [0.5%], P = .01).

Table 1. Population Characteristics of Matched Control Cohort and Patients With Hidradenitis Suppurativa.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matched control cohort | Patients with hidradenitis suppurativa | ||

| Total | 179 734 | 22 468 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 114 446 (63.7) | 14 307 (63.7) | >.99 |

| Female | 65 288 (36.3) | 8161 (36.3) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 33.63 (17.35) | 33.63 (18.14) | |

| ≥60 | 17 050 (9.5) | 2131 (9.5) | .31 |

| <20 | 39 463 (22.0) | 4935 (22.0) | |

| 20 to <30 | 50 529 (28.1) | 6316 (28.1) | |

| 30 to <40 | 33 161 (18.5) | 4144 (18.4) | |

| 40 to <50 | 23 382 (13.0) | 2923 (13.0) | |

| 50 to <60 | 16 149 (9.0) | 2019 (9.0) | |

| 60 to <70 | 9467 (5.3) | 1183 (5.3) | |

| 70 to <80 | 5760 (3.2) | 760 (3.4) | |

| ≥80 | 1823 (1.0) | 188 (0.8) | |

| Insurance type | |||

| Health insurance | 172 646 (96.1) | 21 582 (96.1) | >.99 |

| Medical aids | 7088 (3.9) | 886 (3.9) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 20 629 (11.5) | 2930 (13.0) | <.001 |

| Type 1 diabetes | 482 (0.3) | 97 (0.4) | <.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 9635 (5.4) | 1785 (7.9) | <.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 16 212 (9.0) | 2849 (12.7) | <. 001 |

| Alcoholic liver disease | 712 (0.4) | 116 (0.5) | .008 |

| COPD | 729 (0.4) | 114 (0.5) | .03 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 352 (0.2) | 53 (0.2) | .21 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 680 (0.4) | 140 (0.6) | <.001 |

| Heart failure | 889 (0.5) | 140 (0.6) | .01 |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

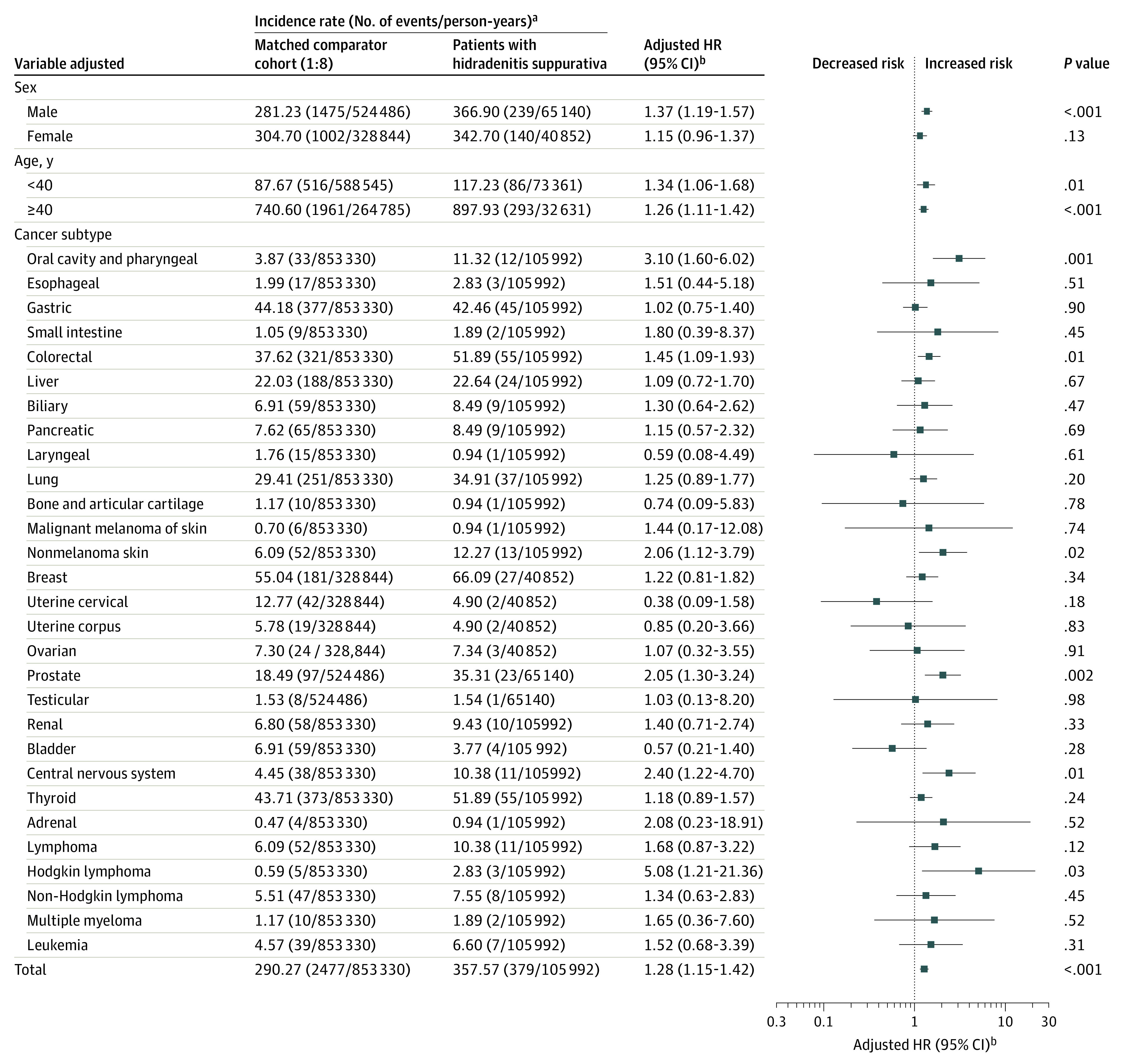

Among 22 468 patients with HS, cancer occurred in 379 individuals (incidence rate, 357.6 cases per 100 000 person-years). In the control cohort, cancer occurred in 2477 of 179 734 participants (incidence rate, 290.3 cases per 100 000 person-years) (Figure; eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Figure. Overall and Specific Cancer Risks in Patients With Hidradenitis Suppurativa Compared With a Matched Control Cohort.

HR indicates hazard ratio.

aIncidence rate per 100 000 person-years.

bAdjusted for the presence of hypertension and dyslipidemia.

After adjustment of the HR (aHR) for comorbidities, the overall risk of cancer was significantly higher in patients with HS than in the control patients (aHR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.15-1.42). Patients with HS were at significantly higher risk for developing Hodgkin lymphoma (aHR, 5.08; 95% CI, 1.21-21.36), oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer (OCPC) (aHR, 3.10; 95% CI, 1.60-6.02), central nervous system (CNS) cancer (aHR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.22-4.70), nonmelanoma skin cancer (aHR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.12-3.79), prostate cancer (aHR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.30-3.24), and colorectal cancer (aHR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.09-1.93).

Overall cancer risk was not significantly higher in female patients with HS than in the female controls (aHR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.96-1.37) after adjusting for comorbidities. Female patients with HS had a higher risk of OCPC (aHR, 3.95; 95% CI, 1.21-12.89) and colorectal cancer (aHR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.12-2.88). Overall cancer risk was significantly higher in male patients with HS than in the male controls (aHR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.19-1.57) after adjusting for comorbidities. Male patients with HS had a higher risk of Hodgkin lymphoma (aHR, 8.68; 95% CI, 1.74-43.28), CNS cancer (aHR, 3.14; 95% CI, 1.38-7.15), OCPC (aHR, 2.80; 95% CI, 1.25-6.25), nonmelanoma skin cancer (aHR, 2.73; 95% CI, 1.33-5.61), and prostate cancer (aHR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.30-3.24) (Table 2).

Table 2. Risks of Overall and Specific Cancers in Male and Female Patients With Hidradenitis Suppurativa (HS) Compared With a Matched Control Cohort.

| Cancer subtype | Male with vs without HS | Female with vs without HS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | P value | Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | P value | |

| Overall | 1.37 (1.19-1.57) | <.001 | 1.15 (0.96-1.37) | .13 |

| Oral cavity and pharyngeal | 2.80 (1.25-6.25) | .01 | 3.95 (1.21-12.89) | .02 |

| Esophageal | 1.61 (0.47-5.53) | .45 | NE | |

| Gastric | 0.93 (0.64-1.35) | .69 | 1.30 (0.74-2.29) | .36 |

| Small intestine | 2.72 (0.55-13.57) | .22 | NE | |

| Colorectal | 1.30 (0.91-1.87) | .16 | 1.79 (1.12-2.88) | .02 |

| Liver | 1.15 (0.72-1.83) | .57 | 0.90 (0.32-2.54) | .85 |

| Biliary | 1.88 (0.82-4.30) | .14 | 0.63 (0.15-2.63) | .52 |

| Pancreatic | 1.75 (0.82-3.76) | .15 | 0.31 (0.04-2.28) | .25 |

| Laryngeal | 0.59 (0.08-4.49) | .61 | NE | |

| Lung | 1.39 (0.95-2.03) | .09 | 0.84 (0.36-1.95) | .68 |

| Bone and articular cartilage | NE | 10.33 (0.63-169.43) | .10 | |

| Malignant melanoma skin | 2.06 (0.23-18.78) | .52 | NE | |

| Nonmelanoma skin | 2.73 (1.33-5.61) | .006 | 1.12 (0.33-3.74) | .86 |

| Breast | NE | 1.22 (0.81-1.82) | .34 | |

| Uterine cervical | NE | 0.38 (0.09-1.58) | .18 | |

| Uterine corpus | NE | 0.85 (0.20-3.66) | .83 | |

| Ovarian | NE | 1.07 (0.32-3.55) | .91 | |

| Prostate | 2.05 (1.30-3.24) | .002 | NE | |

| Testicular | 1.03 (0.13-8.20) | .98 | NE | |

| Renal | 1.26 (0.57-2.80) | .57 | 1.93 (0.54-6.86) | .31 |

| Bladder | 0.65 (0.23-1.80) | .41 | NE | |

| Central nervous system | 3.14 (1.38-7.15) | .006 | 1.49 (0.44-5.05) | .53 |

| Thyroid | 1.52 (0.95-2.42) | .08 | 1.04 (0.73-1.49) | .82 |

| Adrenal | NE | 4.70 (0.28-77.83) | .28 | |

| Lymphoma | 2.39 (1.13-5.03) | .02 | 0.71 (0.17-3.01) | .64 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 8.68 (1.74-43.28) | .008 | NE | |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 1.75 (0.72-4.23) | .22 | 0.78 (0.18-3.34) | .73 |

| Multiple myeloma | 1.13 (0.14-9.27) | .91 | 2.94 (0.30-28.59) | .35 |

| Leukemia | 1.74 (0.66-4.56) | .26 | 1.13 (0.26-4.96) | .87 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NE, not estimated.

Adjusted for the presence of hypertension and dyslipidemia.

After adjustment for comorbidities, overall cancer risks were higher in both younger (age <40 years: aHR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.06-1.68) and older (age ≥40 years: aHR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.11-1.42) patients with HS compared with their age-matched controls without HS. Younger patients with HS had higher risks of CNS cancer (aHR, 3.05; 95% CI, 1.09-8.56) and leukemia (aHR, 2.55; 95% CI, 1.02-6.39) than younger patients in the control cohort. Older patients with HS had higher risks of Hodgkin lymphoma (aHR, 9.04; 95% CI, 1.26-64.85), OCPC (aHR, 3.26; 95% CI, 1.57-6.80), prostate cancer (aHR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.30-3.24), nonmelanoma skin cancer (aHR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.02-3.80), and colorectal cancer (aHR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.04-1.93) than did older patients in the control cohort (Table 3).

Table 3. Risks of Overall and Specific Cancers in Patients With Hidradenitis Suppurativa Compared With a Matched Control Cohort According to Age Group.

| Cancer subtype | Age <40 y | Age ≥40 y | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | P value | Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | P value | |

| Overall | 1.34 (1.06-1.68) | .01 | 1.26 (1.11-1.42) | <.001 |

| Oral cavity and pharyngeal | 2.51 (0.52-12.10) | .25 | 3.26 (1.57-6.80) | .002 |

| Esophageal | NE | 1.51 (0.44-5.18) | .51 | |

| Gastric | 1.01 (0.36-2.87) | .98 | 1.02 (0.74-1.41) | .91 |

| Small intestine | NE | 2.36 (0.49-11.40) | .29 | |

| Colorectal | 1.68 (0.78-3.59) | .19 | 1.41 (1.04-1.93) | .03 |

| Liver | 1.48 (0.33-6.69) | .61 | 1.07 (0.69-1.67) | .76 |

| Biliary | 9.04 (0.56-145.02) | .12 | 1.17 (0.56-2.45) | .68 |

| Pancreatic | NE | 1.27 (0.63-2.57) | .50 | |

| Laryngeal | NE | 0.59 (0.08-4.49) | .61 | |

| Lung | NE | 1.34 (0.95-1.90) | .10 | |

| Bone and articular cartilage | 1.34 (0.16-11.12) | .95 | NE | |

| Malignant melanoma skin | NE | 1.75 (0.20-15.19) | .61 | |

| Nonmelanoma skin | 2.79 (0.56-13.82) | .21 | 1.96 (1.02-3.80) | .045 |

| Breast | 1.23 (0.61-2.49) | .56 | 1.21 (0.74-1.99) | .45 |

| Uterine cervical | 0.44 (0.06-3.29) | .42 | 0.33 (0.05-2.47) | .28 |

| Uterine corpus | NE | 1.26 (0.28-5.60) | .76 | |

| Ovarian | 1.62 (0.19-13.86) | .66 | 0.92 (0.21-3.94) | .91 |

| Prostate | NE | 2.05 (1.30-3.24) | .002 | |

| Testicular | 1.03 (0.13-8.20) | .98 | NE | |

| Renal | 1.65 (0.47-5.75) | .44 | 1.31 (0.59-2.91) | .51 |

| Bladder | NE | 0.60 (0.22-1.66) | .32 | |

| Central nervous system | 3.05 (1.09-8.56) | .03 | 2.02 (0.83-4.93) | .12 |

| Thyroid | 1.27 (0.88-1.83) | .20 | 1.08 (0.69-1.68) | .75 |

| Adrenal | NE | NE | ||

| Lymphoma | 1.53 (0.44-5.31) | .50 | 1.73 (0.81-3.74) | .16 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 2.67 (0.28-25.69) | .40 | 9.04 (1.26-64.85) | .03 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 1.27 (0.28-5.69) | .76 | 1.36 (0.57-3.25) | .49 |

| Multiple myeloma | NE | 1.65 (0.36-7.60) | .52 | |

| Leukemia | 2.55 (1.02-6.39) | .046 | 0.45 (0.06-3.34) | .43 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NE, not estimated.

Adjusted for the presence of hypertension and dyslipidemia.

Results from the subgroup analyses based on the severity of HS are reported in Table 4. After adjustment for comorbidities, patients with moderate to severe HS had a higher risk for overall cancer (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.15-1.92) compared with patients with mild HS (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.11-1.40). Adjusted HRs of most cancers in patients with moderate to severe HS were higher than those in patients with mild disease, except for nonmelanoma skin cancer, prostate cancer, lymphoma, and leukemia. The risk of Hodgkin lymphoma in patients with moderate to severe HS (aHR, 13.28; 95% CI, 1.49-118.43) was significantly higher than that in patients with mild disease (aHR, 3.89; 95% CI, 0.75-20.14).

Table 4. Risks of Overall and Specific Cancers in Patients With Mild or Moderate/Severe Hidradenitis Suppurativa (HS) vs Matched Control Cohort.

| Cancer subtype | Group | Event, n | Total, n | Person-years | Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Control | 2477 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | <.001 |

| HS mild | 318 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 1.24 (1.11-1.40) | <.001 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 61 | 4137 | 16 674 | 1.49 (1.15-1.92) | .002 | |

| Oral cavity and pharyngeal | Control | 33 | 179 734 | 853 330. | 1 [Reference] | .004 |

| HS mild | 10 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 3.07 (1.51-6.25) | .002 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 2 | 4137 | 16 674 | 3.24 (0.71-13.62) | .11 | |

| Esophageal | Control | 17 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .51 |

| HS mild | 2 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 1.19 (0.27-5.17) | .82 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 1 | 4137 | 16 674 | 3.32 (0.44-25.24) | .25 | |

| Gastric | Control | 377 | 179 734 | 853 3304 | 1 [Reference] | .89 |

| HS mild | 37 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 0.99 (0.71-1.39) | .95 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 8 | 4137 | 16 674 | 1.18 (0.59-2.39) | .64 | |

| Small intestine | Control | 9 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .14 |

| HS mild | 1 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 1.01 (0.13-8.02) | .99 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 1 | 4137 | 16 674 | 8.06 (1.00-64.92) | .05 | |

| Colorectal | Control | 321 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .03 |

| HS mild | 45 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 1.40 (1.02-1.91) | .04 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 10 | 4137 | 16 674 | 1.74 (0.92-3.28) | .09 | |

| Liver | Control | 188 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .49 |

| HS mild | 18 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 0.99 (0.61-1.60) | .96 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 6 | 4137 | 16 674 | 1.65 (0.73-3.72) | .23 | |

| Biliary | Control | 59 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .49 |

| HS mild | 7 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 1.15 (0.52-2.52) | .73 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 2 | 4137 | 16 674 | 2.32 (0.56-9.61) | .25 | |

| Pancreatic | Control | 65 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .18 |

| HS mild | 6 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 0.88 (0.38-2.05) | .77 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 3 | 4137 | 16 674 | 2.97 (0.92-9.52) | .07 | |

| Laryngeal | Control | 15 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .94 |

| HS mild | 1 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 0.70 (0.09-5.31) | .73 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 0 | 4137 | 16 674 | NE | ||

| Lung | Control | 251 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .41 |

| HS mild | 31 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 1.23 (0.84-1.78) | .29 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 6 | 4137 | 16 674 | 1.43 (0.64-3.22) | .39 | |

| Bone and articular cartilage | Control | 10 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .10 |

| HS mild | 1 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 0.95 (0.12-7.45) | .96 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 0 | 4137 | 16 674 | NE | ||

| Malignant melanoma skin | Control | 6 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .91 |

| HS mild | 1 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 1.61 (0.19-13.50) | .66 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 0 | 4137 | 16 674 | NE | ||

| Nonmelanoma skin | Control | 52 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .049 |

| HS mild | 12 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 2.20 (1.17-4.14) | .01 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 1 | 4137 | 16 674 | 1.15 (0.16-8.39) | .89 | |

| Breast | Control | 181 | 65 288 | 328 844 | 1 [Reference] | .63 |

| HS mild | 25 | 7538 | 38 483 | 1.21 (0.79-1.83) | .38 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 2 | 623 | 2369 | 1.38 (0.34-5.56) | .65 | |

| Uterine cervical | Control | 42 | 65 288 | 328 844 | 1 [Reference] | .17 |

| HS mild | 1 | 7538 | 38 483 | 0.21 (0.03-1.49) | .12 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 1 | 623 | 2369 | 2.77 (0.38-20.21) | .32 | |

| Uterine corpus | Control | 19 | 65 288 | 328 844 | 1 [Reference] | .99 |

| HS mild | 2 | 7538 | 38 482 | 0.91 (0.21-3.91) | .90 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 0 | 623 | 2369 | NE | ||

| Ovarian | Control | 24 | 65 288 | 328 844 | 1 [Reference] | .98 |

| HS mild | 3 | 7538 | 38 482 | 1.14 (0.34-3.81) | .83 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 0 | 623 | 2369 | NE | ||

| Prostate | Control | 97 | 114 446 | 524 486 | 1 [Reference] | .005 |

| HS mild | 21 | 10 793 | 50 835 | 2.21 (1.38-3.54) | .001 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 2 | 3514 | 14 305 | 1.18 (0.29-4.79) | .82 | |

| Testicular | Control | 8 | 114 446 | 524 486 | 1 [Reference] | .95 |

| HS mild | 1 | 10 793 | 50 835 | 1.41 (0.18-11.31) | .75 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 0 | 3514 | 14 305 | NE | ||

| Renal | Control | 58 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .02 |

| HS mild | 5 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 0.86 (0.34-2.14) | .75 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 5 | 4137 | 16 674 | 3.73 (1.48-9.39) | .005 | |

| Bladder | Control | 59 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .74 |

| HS mild | 4 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 0.67 (0.24-1.84) | .44 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 0 | 4137 | 16 674 | NE | ||

| Central nervous system | Control | 38 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .01 |

| HS mild | 11 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 2.79 (1.43-5.48) | .003 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 0 | 4137 | 16 674 | NE | ||

| Thyroid | Control | 373 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .21 |

| HS mild | 45 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 1.11 (0.81-1.51) | .52 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 10 | 4137 | 16 674 | 1.72 (0.91-3.23) | .09 | |

| Adrenal | Control | 4 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .76 |

| HS mild | 1 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 2.30 (0.25-20.96) | .46 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 0 | 4137 | 16 674 | NE | ||

| Lymphoma | Control | 52 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .25 |

| HS mild | 10 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 1.79 (0.91-3.53) | .09 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 1 | 4137 | 16 674 | 1.03 (0.14-7.51) | .98 | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | Control | 5 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .04 |

| HS mild | 2 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 3.89 (0.75-20.14) | .11 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 1 | 4137 | 16 674 | 13.28 (1.49-118.43) | .02 | |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Control | 47 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .50 |

| HS mild | 8 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 1.57 (0.74-3.33) | .24 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 0 | 4137 | 16 674 | NE | ||

| Multiple myeloma | Control | 10 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .71 |

| HS mild | 2 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 1.92 (0.42-8.81) | .40 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 0 | 4137 | 16 674 | NE | ||

| Leukemia | Control | 39 | 179 734 | 853 330 | 1 [Reference] | .60 |

| HS mild | 6 | 18 331 | 89 318 | 1.54 (0.65-3.64) | .33 | |

| HS moderate/severe | 1 | 4137 | 16 674 | 1.39 (0.19-10.19) | .75 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; HS, hidradenitis suppurativa; NE, not estimated.

Adjusted for the presence of hypertension and dyslipidemia.

There were 3 incident cancer cases among patients in the entire cohort with a history of anti-TFN-α use. The incidence rate of cancer among patients with HS who received anti-TNF-α treatment was high (1030 cases per 100 000 person-years) in the subgroup analysis. However, the HR for anti-TNF-α users could not be estimated because of the matched nature of the data.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the largest nationwide, population-based cohort study of the overall and specific cancer risks in patients with HS. An association between HS and the development of specific cancers has been suggested.15,16,17,18,19,20 However, to our knowledge, the only study evaluating the risk of overall cancer used a relatively small cohort of hospitalized patients with HS in Sweden.15 Moreover, previous studies suggesting associations between HS and cancer were conducted in Western countries. Studies from Asian countries suggesting racial differences in HS characteristics9,22,23 demonstrated the need for us to conduct a nationwide, population-based study to evaluate the overall and specific cancer risks in patients with HS in the Republic of Korea.

The present study found a significant increase in overall cancer risk among patients with HS, which is inconsistent with the findings of the previous Swedish study that included 2119 patients with HS with a mean follow-up period of 9.8 years.15 The increased relative risk of any cancer in the patients with HS in the previous study was 50%. However, the participants in the previous study were hospitalized and might have had more comorbidities than noted in our population, which could increase the risk of cancer.

For specific cancers, we observed that the risk of OCPC and nonmelanoma skin cancer was significantly increased, which is consistent with the Swedish study.15 Both cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption have been identified as independent factors in the development of OCPC.24,25 Although the association between cigarette smoking and HS is controversial, a recent, large cohort study reported an association between smoking and a 2-fold increase in the incidence of HS.26 Smoking is hypothesized to be related to HS through nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, which can be found on cells assumed to be involved in the pathogenesis of HS.27 Smoking is also thought to alter the microbiome of patients with HS by increasing colonization of Staphylococcus aureus,28 which has been shown to possibly enhance the synthesis of acetylcholine.29 The combined consequences may include infundibular hyperkeratosis with occlusion and eventually lead to follicular rupture.30 In addition, smoking may be a factor in the development of HS by inducing a proinflammatory state through the release of cytokines, such as TNF-α.31 A recent population-based study reported that alcohol overuse is more prevalent in people with HS compared with people without HS.32 Alcohol is not considered to be a factor in the development of HS, but given the negative physical and psychosocial consequences associated with the disease,33 patients with HS may be at risk for alcohol overuse.32 Thus, the increased risk of OCPC in patients with HS in the present study may be partially attributed to these environmental factors. The effect of HS in the development of OCPC should be further assessed in future studies.

Rare cases of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) developing in patients with HS have also been reported.16,18,34,35 Although generally well differentiated, SCC arising from HS may be more aggressive and have a worse prognosis than SCC not associated with HS. Squamous cell carcinoma developing in patients with HS is more common in men and lesions generally present in the perineal, perianal, and gluteal regions. Researchers have suggested that human papillomavirus, smoking, and chronic inflammation in patients with HS play a role in the development of SCC.16,34,35 The Swedish cohort study found that HS was associated with a 4.6-fold increase in the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer.15 The present study, which featured a large, nationwide cohort of patients with HS and matched controls, noted an apparent relatively modest increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer in patients with HS. The relatively lower incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer in Asian populations may explain these results.36

The present study also identified associations between HS and risk of CNS, colorectal, and prostate cancer. Smoking and alcohol use do not appear to be associated with increased risk of CNS cancers.37,38 Among HS comorbidities previously reported,39 obesity has been linked to the increased risk of CNS cancer because obesity is a potential risk factor for overall brain and CNS tumors.40 Potential comorbidities of HS, such as smoking, excessive alcohol use, and obesity, may all contribute to the increased risk of colorectal cancer noted in this study.41,42,43 Although previous studies have failed to consistently identify associations between androgens and HS,36,44 androgens have been suggested to at least partially contribute to the development of HS, as some patients with HS have shown improvements during pregnancy or with antiandrogen therapy.45 The pivotal role of androgen signaling in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer has been established.46 The increased risk of prostate cancer among patients with HS in the present study might provide another clue that androgens may contribute to the development of HS.

Chronic inflammation associated with HS has been suggested to contribute to the development of malignant lymphomas. In a case-control analysis, there was a 2.03 greater odds of lymphoma in patients with HS relative to control individuals, although the increased odds were not statistically significant.39 A recent cross-sectional study found that both males and females with HS were more likely to have malignant lymphomas than the general population (odds ratio, 2.00 for non-Hodgkin lymphoma and 2.26 for Hodgkin lymphoma), with male patients having a higher prevalence of lymphoma than female patients.19 In our study, patients with HS had an increased risk of Hodgkin lymphoma, but in the subgroup analysis by sex, only male patients with HS had an increased risk of Hodgkin lymphoma. In addition, the risk of Hodgkin lymphoma was higher in patients with moderate to severe HS than in patients with mild disease, suggesting a substantial association between HS and Hodgkin lymphoma. The risk of Hodgkin lymphoma in this study appeared to be greater than in the previous study.19 Whether this finding is associated with different study design or participant ethnicity needs further examination.

According to the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the risk factors for OCPC and colorectal cancer, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and obesity, are more prevalent in men than women in Korea.47 This difference in the distribution of these risk factors could have contributed to the increased risk for OCPC and colorectal cancer in female patients with HS in this study. The differences in cancer risk between male and female patients with HS in this study might also have been associated with the combined different susceptibility to environmental factors and genetic and hormonal factors that affect the manifestation and activity of HS.

Hidradenitis suppurativa was associated with an increased overall risk of cancer, regardless of patient age, but the risk of specific cancers appears to differ depending on patient age. Overall cancer risk showed a tendency to increase with worsening HS severity, reinforcing the possibility of an association between HS and cancer development. However, we could not identify tendencies in some specific cancers, such as nonmelanoma skin cancer, CNS cancer, and prostate cancer, because the number of occurrences of those cancers was too small in the group with moderate to severe HS. Anti-TNF-α treatment may also increase the risk of cancer. However, there were only 3 incident cancer cases among individuals in the entire cohort who ever received anti-TFN-α, suggesting that the association between anti-TNF-α treatment and the development of cancer was minimal in the HS cohort. Additional studies would be necessary to estimate the association between anti-TNF-α treatment and cancer development in patients with HS.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has limitations. First, the true incidence of HS may have been underestimated by missing undiagnosed cases in this nationwide population-based study.48 Second, adjustment for potentially confounding factors, such as smoking status, alcohol use, and obesity, was not possible, because that type of information was not available in the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database. However, to minimize the effect of confounders, we not only matched controls by age, sex, and income, but also made adjustments for different comorbidities between patients with and people without HS in our cohort. Third, because information on the extent and severity of HS according to validated criteria is not available in the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database, we surmised that patients with mild HS would not require surgical or systemic anti-TNF-α treatments and used those treatment criteria to differentiate between patients with mild and those with moderate or severe HS. Fourth, the findings in this study may not be applicable to patients of different ethnicities.

Our study used a retrospective cohort design assessing the risk of cancers in incident cases of HS. Thus, we believe that the evidence from the present study is stronger than that of other cross-sectional or association studies.

Conclusion

Hidradenitis suppurativa appears to be associated with an overall risk of cancer and several specific cancers, such as OCPC, nonmelanoma skin cancer, CNS cancer, colorectal cancer, and prostate cancer. This study suggests that more intense cancer surveillance may be warranted in patients with HS. For early detection of skin cancer, more aggressive histologic examination and a high level of suspicion are required. Lifestyle modifications in patients with HS to address behaviors such as smoking or alcohol use or conditions such as obesity should be emphasized. If patients develop any signs or symptoms suggesting Hodgkin lymphoma, such as painless lymphadenopathy, persistent fatigue, unexplained fever, night sweats, or unexplained weight loss, more aggressive laboratory testing, imaging studies, and histologic examinations are recommended, especially in men with HS. Studies on various ethnic groups to evaluate the risk of cancer in patients with HS are needed.

eTable 1. International Statistical Classification of Disease, 10th Revision Codes for Specific Cancers

eTable 2. Risks of Overall and Specific Cancers in Patients With Hidradenitis Suppurativa Compared With a Matched Comparator Cohort

eFigure. Flow Chart of the Study

References

- 1.Jansen T, Plewig G. Acne inversa. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37(2):96-100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onderdijk AJ, van der Zee HH, Esmann S, et al. Depression in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(4):473-478. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shavit E, Dreiher J, Freud T, Halevy S, Vinker S, Cohen AD. Psychiatric comorbidities in 3207 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(2):371-376. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vangipuram R, Vaidya T, Jandarov R, Alikhan A. Factors contributing to depression and chronic pain in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from a single-center retrospective review. Dermatology. 2016;232(6):692-695. doi: 10.1159/000453259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tzellos T, Yang H, Mu F, Calimlim B, Signorovitch J. Impact of hidradenitis suppurativa on work loss, indirect costs and income. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(1):147-154. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy S, Strunk A, Garg A. Comparative overall comorbidity burden among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(7):797-802. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phan K, Charlton O, Smith SD. Hidradenitis suppurativa and diabetes mellitus: updated systematic review and adjusted meta-analysis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44(4):e126-e132. doi: 10.1111/ced.13922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tiri H, Jokelainen J, Timonen M, Tasanen K, Huilaja L. Substantially reduced life expectancy in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a Finnish nationwide registry study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(6):1543-1544. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JH, Kwon HS, Jung HM, Kim GM, Bae JM. Prevalence and comorbidities associated with hidradenitis suppurativa in Korea: a nationwide population-based study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(10):1784-1790. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller IM, McAndrew RJ, Hamzavi I. Prevalence, risk factors, and comorbidities of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34(1):7-16. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prens E, Deckers I. Pathophysiology of hidradenitis suppurativa: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5)(suppl 1):S8-S11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bechara FG, Sand M, Skrygan M, Kreuter A, Altmeyer P, Gambichler T. Acne inversa: evaluating antimicrobial peptides and proteins. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24(4):393-397. doi: 10.5021/ad.2012.24.4.393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Zee HH, de Ruiter L, van den Broecke DG, Dik WA, Laman JD, Prens EP. Elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: a rationale for targeting TNF-α and IL-1β. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(6):1292-1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10254.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlapbach C, Hänni T, Yawalkar N, Hunger RE. Expression of the IL-23/Th17 pathway in lesions of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(4):790-798. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lapins J, Ye W, Nyrén O, Emtestam L. Incidence of cancer among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(6):730-734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jourabchi N, Fischer AH, Cimino-Mathews A, Waters KM, Okoye GA. Squamous cell carcinoma complicating a chronic lesion of hidradenitis suppurativa: a case report and review of the literature. Int Wound J. 2017;14(2):435-438. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manolitsas T, Biankin S, Jaworski R, Wain G. Vulval squamous cell carcinoma arising in chronic hidradenitis suppurativa. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75(2):285-288. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rastogi S, Patel KR, Singam V, et al. Vulvar cancer association with groin hidradenitis suppurativa: a large, urban, midwestern US patient population study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(3):808-810. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tannenbaum R, Strunk A, Garg A. Association between hidradenitis suppurativa and lymphoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(5):624-625. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon S. Thirty years of national health insurance in South Korea: lessons for achieving universal health care coverage. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24(1):63-71. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi E, Cook AR, Chandran NS. Hidradenitis suppurativa: an Asian perspective from a Singaporean institute. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4(4):281-285. doi: 10.1159/000481836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurokawa I, Hayashi N; Japan Acne Research Society . Questionnaire surveillance of hidradenitis suppurativa in Japan. J Dermatol. 2015;42(7):747-749. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shapiro JA, Jacobs EJ, Thun MJ. Cigar smoking in men and risk of death from tobacco-related cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(4):333-337. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.4.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu Y, Sobue T, Kitamura T, et al. Cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer in the Japanese: a population-based cohort study in Japan. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2018;27(2):171-179. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garg A, Papagermanos V, Midura M, Strunk A. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa among tobacco smokers: a population-based retrospective analysis in the USA. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(3):709-714. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurzen H, Wessler I, Kirkpatrick CJ, Kawashima K, Grando SA. The non-neuronal cholinergic system of human skin. Horm Metab Res. 2007;39(2):125-135. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-961816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pavia CS, Pierre A, Nowakowski J. Antimicrobial activity of nicotine against a spectrum of bacterial and fungal pathogens. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49(7):675-676. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-7-675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawashima K, Fujii T. The lymphocytic cholinergic system and its contribution to the regulation of immune activity. Life Sci. 2003;74(6):675-696. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurzen H, Kurokawa I, Jemec GB, et al. What causes hidradenitis suppurativa? Exp Dermatol. 2008;17(5):455-456. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00712.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeong SH, Park JH, Kim JN, et al. Up-regulation of TNF-alpha secretion by cigarette smoke is mediated by Egr-1 in HaCaT human keratinocytes. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19(8):e206-e212. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.01050.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garg A, Papagermanos V, Midura M, Strunk A, Merson J. Opioid, alcohol, and cannabis misuse among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based analysis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(3):495-500.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gooderham M, Papp K. The psychosocial impact of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5)(suppl 1):S19-S22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makris GM, Poulakaki N, Papanota AM, Kotsifa E, Sergentanis TN, Psaltopoulou T. Vulvar, perianal and perineal cancer after hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(1):107-115. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lavogiez C, Delaporte E, Darras-Vercambre S, et al. Clinicopathological study of 13 cases of squamous cell carcinoma complicating hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2010;220(2):147-153. doi: 10.1159/000269836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mortimer PS, Dawber RP, Gales MA, Moore RA. Mediation of hidradenitis suppurativa by androgens. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1986;292(6515):245-248.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=2936421&dopt=Abstract doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6515.245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qi ZY, Shao C, Yang C, Wang Z, Hui GZ. Alcohol consumption and risk of glioma: a meta-analysis of 19 observational studies. Nutrients. 2014;6(2):504-516. doi: 10.3390/nu6020504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braganza MZ, Rajaraman P, Park Y, et al. Cigarette smoking, alcohol intake, and risk of glioma in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(1):242-248. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shlyankevich J, Chen AJ, Kim GE, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa is a systemic disease with substantial comorbidity burden: a chart-verified case-control analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(6):1144-1150. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sergentanis TN, Tsivgoulis G, Perlepe C, et al. Obesity and risk for BRAIN/CNS tumors, gliomas and meningiomas: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0136974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsoi KK, Pau CY, Wu WK, Chan FK, Griffiths S, Sung JJ. Cigarette smoking and the risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(6):682-688.e1, 5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cho E, Lee JE, Rimm EB, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci EL. Alcohol consumption and the risk of colon cancer by family history of colorectal cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(2):413-419. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.022145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobs ET, Ahnen DJ, Ashbeck EL, et al. Association between body mass index and colorectal neoplasia at follow-up colonoscopy: a pooling study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(6):657-666. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jemec GB. The symptomatology of hidradenitis suppurativa in women. Br J Dermatol. 1988;119(3):345-350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb03227.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Włodarek K, Ponikowska M, Matusiak Ł, Szepietowski JC. Biologics for hidradenitis suppurativa: an update. Immunotherapy. 2019;11(1):45-59. doi: 10.2217/imt-2018-0090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huggins C, Hodges CV. Studies on prostatic cancer. Cancer Res. 1941;1(4):293-297. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Accessed March 15, 2020. https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/sub01/sub01_05.do

- 48.Ingram JR, Jenkins-Jones S, Knipe DW, Morgan CLI, Cannings-John R, Piguet V. Population-based Clinical Practice Research Datalink study using algorithm modelling to identify the true burden of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(4):917-924. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. International Statistical Classification of Disease, 10th Revision Codes for Specific Cancers

eTable 2. Risks of Overall and Specific Cancers in Patients With Hidradenitis Suppurativa Compared With a Matched Comparator Cohort

eFigure. Flow Chart of the Study