Abstract

Plastic wastes are environmentally problematic and costly to treat, but they also represent a vast untapped resource for the renewable chemical and fuel production. Pyrolysis has received extensive attention in the treatment of plastic wastes because of its technical maturity. A sole polymer in the waste plastic is easy to recycle by any means of physical or chemical techniques. However, the majority of plastic in life are mixtures and they are hard to separate, which make pyrolysis of plastic complicated compared with pure plastic because of its difference in physical/chemical properties. This work focuses on the synergistic effect and its impact on chlorine removal from the pyrolysis of chlorinated plastic mixtures. The pyrolysis behavior of plastic mixtures was investigated in terms of thermogravimetric analysis, and the corresponding kinetics were analyzed according to the distributed activation energy model (DAEM). The results show that the synergistic effect existed in the pyrolysis of a plastic mixture of LLDPE, PP, and PVC, and the DAEM could well predict the kinetics behavior. The decomposition of LLDPE/PP mixtures occurred earlier than that of calculated ones. However, the synergistic effect weakened with the increase of LLDPE in the mixtures. As for the chlorine removal, the LLDPE and PP hindered the chlorine removal from PVC during the plastic mixture pyrolysis. A noticeable negative effect on dechlorination was observed after the introduction of LLDPE or PP. Besides, the chlorine-releasing temperature became higher during the pyrolysis of plastic mixtures ([LLDPE/PVC (1:1), PP/PVC (1:1), and LLDPE/PP/PVC (1:1:1)]. These results imply that the treatment of chlorinated plastic wastes was more difficult than that of PVC in thermal conversion. In other words, more attention should be paid to both the high-temperature chlorine corrosion and high-efficient chlorine removal in practical. These data are helpful for the treatment and thermal utilization of the yearly increased plastic wastes.

1. Introduction

Plastic is visible in both agricultural and industrial areas, small to everyday items, and large to aerospace equipment. It plays an irreplaceable role in people daily lives. According to statistics, the annual global plastic production had sharply risen from 2 million tons in 1950 to 348 million tons in 2017, of which 17.7% in NAFTA, 4% in Latin America, 18% in Europe, 7.1% in Middle East Africa, 2.6% in CIS, and 50.1% in Asia (29.4% in China, 3.9% in Japan, and 16.8% in Rest of Asia).1 In the meanwhile, the global production of plastic wastes reached 6 billion tons in 2015, of which 76% were landfilled, 12% were burnt, 3% entered the ocean, and only 9% were recycled.2 It has been a serious threat to the human being living environment because of the huge amount and ineffective treatment. Thus, it was necessary to find a feasible way to address plastic waste issues and to relieve environmental stress.

The pyrolysis has been received extensive attention because of its flexibility to generate a combination of solid, liquid, and gaseous products in different proportions only by varying the operating parameters such as temperature or heating rate.3−6 The chlorine was commonly removed from plastic mixtures before the pyrolysis step.7 Miranda et al.,8 stated that the chlorine in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) could be completely removed at a temperature of 375 °C, and the synergistic effect during the co-pyrolysis of PS and PVC was also observed in their work. Wu et al.,9 observed the inhibition between polyethylene (PE) and PVC during co-pyrolysis. Many researchers studied on the pyrolysis kinetics for the reactor design and process optimization. Aboulkas et al.,10 reported that the pyrolysis of PE and polypropylene (PP) could be characterized by the one-step model, and the activation energy of PE and PP fluctuated slightly at the conversion rate of 0.1–0.9. However, Xu et al.,11 stated that the pyrolysis behavior of low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and PP could be accurately described by the R2 (shrink ball) and R3 (contracted cylinder) models while the first and second stages of PVC pyrolysis belonged to A3 (three-dimensional nucleation) and D3 (three-dimensional diffusion) models. Qiao et al.,12 believed that the frequency factor and activation energy presented the same variation trend. Soria-Verdugo et al.,13 found that the kinetics parameters evaluated by Ozawa–Flynn–Wall and Kissinger–Akahira–Sunose methods were similar to the distributed activation energy model (DAEM). Some other works investigated on the co-pyrolysis of plastics, mainly focusing on the oil quality.14,15 All these works have made great contributions to the understanding of plastic pyrolysis behaviors and oil quality. However, the synergistic effect during pyrolysis and its impact on chlorine removal are still required to explore. In practical, the chlorine removal is quite important for the chlorinated organic wastes because of the acidic corrosion to equipment and environmental pollution, resulting from the dioxin formation.

In this work, the pyrolysis behaviors and kinetics of plastic mixture of linear LLDPE, PP, and PVC were investigated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) under various heating rates. The kinetics parameters were derived according to the DAEM. The synergistic effects during the plastic mixture pyrolysis were studied, and its impact on the chlorine removal was also discussed. This study is helpful for the harmlessness treatment and thermal utilization of plastic waste, especially the organic chlorinated wastes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Preparation

Three typical plastics, including linear LLDPE, PP, and PVC, were obtained from Exxon Corporation, China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation Maoming Branch, and Hanwha. Their density were 0.93, 0.98, and 1.41 g/cm3, respectively. There was no long chain branch in the structure of LLDPE compared to LDPE but more short branches compared to HDPE. All the materials were dried in an electric oven at ∼70 °C for 24 h to eliminate the influence of moisture and utilized as it was without further purification. The powdered samples with a diameter of around 100 mesh were used for TGA. The proximate and ultimate analysis of samples is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Proximate and Ultimate Analysis of Materials.

| ultimate

analysis (wt %a) |

proximate

analysis (wt %a) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| samples | C | H | O | N | S | Cl | M | Ash | VM | FC |

| LLDPE | 85.61 | 14.29 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 99.86 | 0.07 |

| PP | 85.71 | 14.18 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 99.90 | 0.03 |

| PVC | 37.78 | 4.83 | 0.36 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 56.73 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 96.52 | 3.47 |

On an air dry base; M, inherent moisture; VM, volatile matter; and FC, fixed carbon.

2.2. Pyrolysis Behavior

The pyrolysis was carried out in a TG analyzer (LabsysEvo, SETARAM). Before the experiments, the crucible made of Al2O3 was placed in a muffle furnace at 900 °C for 1 h to reduce experimental errors. The inner tube of the thermogravimeter was flushed using a large flow rate of nitrogen (99.999%) for approximately 20 s. For each run, the sample mass was around 20 ± 0.5 mg, and the nitrogen flow rate was 20 mL/min. All the tests followed the same procedure: steady at 30 °C for 5 min and then heated up to 800 °C under the nonisothermal conditions at a constant rate of 10, 20, 30, and 40 K/min. The plastic mixtures were prepared by mixing PP, LLDPE, and PVC, according to various proportions as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Composition of Plastic Mixturesa.

| heating

rate (K/min) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. | samples | mixing ratio | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 |

| 1 | LLDPE | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| 2 | PP | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| 3 | PVC | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| 4 | LLDPE/PP | 1/1 | √ | √ | √ | |

| 5 | LLDPE/PP | 1/2 | √ | √ | √ | |

| 6 | LLDPE/PP | 1/3 | √ | √ | √ | |

| 7 | LLDPE/PP/PVC | 3/2/1 | √ | √ | √ | |

| 8 | LLDPE/PVC | 1/1 | √ | |||

| 9 | PP/PVC | 1/1 | √ | |||

| 10 | LLDPE/PP/PVC | 1/1/1 | √ | |||

√ parameters utilized in the pyrolysis of plastic mixture; not applicable.

2.3. Kinetics Analysis

The DAEM was based on the hypothesis of infinite parallel reaction and the activation energy distribution. It could be written as follows12,16

| 1 |

V—volatile matter at a given time, %; V*—total volatile matter, %; T—pyrolysis temperature, K; Eτ–—activation energy at a given time (τ); Aτ—activation energy at a given time (τ); E—activation energy, kJ/mol; A—frequency factor, 1/min; and gas constant, R = 8.314 kJ/(mol·K). f(E) was a function of the activation energy E and met the conditions

| 2 |

Eq 1 could be then simplified as

| 3 |

The pyrolysis temperature (T) at a given time (τ) could be expressed by the heating rate β as follows

| 4 |

Equation 3 was then derived as

| 5 |

Equation 5 fulfills the format of Y = aX + b, in which Y and X are ln(β/T2) and 1/T, respectively. a is the slope, and b is the intercept of the fitting line of ln(β/T2) versus 1/T. According to the TGA data, the activation energy (E) and frequency factor (A) could be obtained by E = −Ra and A = exp(b – 0.6075) × E/R, respectively.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Pyrolysis Behaviors of LLDPE, PP, and PVC

Table 3 summarizes the characteristic parameters of the pyrolysis of individual polymers (LLDPE, PP, and PVC) under various nonisothermal heating rates as 10, 30, and 40 K/min, respectively. The thermogravimetry/ derivative thermogravimetry (TG/DTG) data are presented in Figure S1. Both LLDPE and PP presented a similar pyrolysis behavior with only one reaction stage, which could be ascribed to their similar chemical structure. This was consistent with those reported by Aboulkas et al.,10 and Xu et al.,.11 At the heating rate of 10 K/min, both LLDPE and PP were melted at a low temperature and then started to decompose at 460 and 434 °C, respectively. At this stage, LLDPE and PP began to decompose because of the random chain scission, resulting in a loss of polymer molecular weight. The pyrolysis products were mainly macromolecular with small amount of volatile gases at this stage. These macromolecular products could be further decomposed by heating.17,18 Additionally, the temperature (TP) for maximum weight loss rate occurred at 483 and 467 °C for LLDPE and PP, respectively, suggesting a higher thermal stability of LLDPE than PP. This was because the high number of tertiary carbon existed in the molecule chain of PP, which provided more stable-free radicals than secondary of primary carbon. In other words, higher branching degree of PP (compared to LLDPE) resulted in a weaker link in the molecular chain of PP. Thus, the PP was easier than LLDPE to decompose. Besides, some secondary condensation reactions could also happen during the pyrolysis. Liu et al.,17 observed an exothermic peak at the later stage of LLDPE and PP pyrolysis.

Table 3. Pyrolysis Parameters of Individual Components at Different Heating Ratesa.

| polymers | heating rate (K/min) | DTGp (%/K) | Tp (°C) | Ti (°C) | Tf (°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLDPE | 10 | –3.55 | 483 | 460 | 505 | |

| 30 | –2.84 | 505 | 482 | 534 | ||

| 40 | –2.39 | 511 | 490 | 544 | ||

| PP | 10 | –2.93 | 467 | 434 | 489 | |

| 30 | –2.47 | 487 | 451 | 521 | ||

| 40 | –2.17 | 492 | 463 | 529 | ||

| PVCb | 10 | Stage 1 | –1.37 | 288 | 272 | 379 |

| Stage 2 | –0.36 | 467 | 379 | 556 | ||

| 30 | Stage 1 | –1.06 | 316 | 294 | 404 | |

| Stage 2 | –0.31 | 489 | 404 | 563 | ||

| 40 | Stage 1 | –0.93 | 326 | 300 | 415 | |

| Stage 2 | –0.30 | 498 | 415 | 573 |

Ti: the temperature at the TG value of 95% was defined as the initial decomposition temperature of the pyrolysis. Tf: the final temperature of the pyrolysis. Tp: the maximum mass loss rate temperature. DTGp: the maximum mass loss rate.

For samples containing PVC, the Ti at stage one was defined as chlorine-release temperature, referring to yuan et al.,19

Contrary to LLDPE and PP, the pyrolysis of PVC could be clearly divided into two stages as dehydrochlorination with the temperature range of 272–379 °C and the hydrocarbon decomposition at the temperature range of 379–556 °C at the heating rate of 10 K/min. This was because the chlorine was usually removed from plastic mixtures prior to the pyrolysis step.7 The DTGP at 288 °C was significantly higher than that at 467 °C, indicating that the decomposition of PVC mainly appeared at the first stage. At this stage, the main products were hydrogen chloride (HCl) and a small amount of gases with small molecules (e.g., hydrogen, methane, ethane,19 and ethylene9,20). The categories of products at the second pyrolysis stage were very complicated, mainly derived from the pyrolysis of polyene-conjugated structure in PVC at high temperatures. The main products from this stage consisted of aliphatic compounds, aromatic compounds (benzene, toluene, o-xylene, chlorobenzene, etc.), and chars.21,22

LLDPE, PP, and PVC presented a similar feature in the aspect of the pyrolysis parameters. The initial (Ti) temperature, maximum weight loss (Tp), and final temperatures (Tf) of LLDPE, PP, and PVC moved to higher temperatures with the heating rate (increasing from 10 to 40 K/min). In the meanwhile, the DTGP values became lower with the heating rates, which could be attributed to thermal lag and heat transfer limitations. The temperature difference between the furnace and samples was more and more noticeable with the heating rates. Besides, the pyrolysis reactions also depended on the heating rates. The DTGP values started decreasing, indicating a lower decomposition rate for LLDPE and PP and a lower chlorine removal and decomposition rate for PVC.

3.2. Pyrolysis of Plastic Mixtures

Table 4 presents the basic data from the pyrolysis of plastic mixtures. These parameters were quite different from those for sole plastic pyrolysis. For LLDPE/PP mixtures, the initial decomposition temperature (Ti) and the maximum mass loss rate temperature (TP) decreased at a heating rate of 10 K/min, when the mass ratio of LLDPE to PP was decreased from 1:1 to 1:3. This indicates that the thermal stability of the LLDPE/PP mixtures tended to reduce with the PP proportion in the mixture.

Table 4. Pyrolysis Parameters of Plastic Mixtures at Various Heating Rates.

| polymers | heating rate (K/min) | DTGp (%/K) | Tp (°C) | Ti (°C) | Tf (°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLDPE:PP(1:1) | 10 | –3.31 | 471 | 441 | 494 | |

| 30 | –2.83 | 493 | 466 | 522 | ||

| 40 | –2.32 | 498 | 469 | 534 | ||

| LLDPE:PP(1:2) | 10 | –3.05 | 469 | 435 | 493 | |

| 30 | –2.62 | 491 | 456 | 521 | ||

| 40 | –2.26 | 497 | 465 | 530 | ||

| LLDPE:PP(1:3) | 10 | –2.81 | 466 | 427 | 491 | |

| 30 | –2.54 | 489 | 455 | 520 | ||

| 40 | –2.20 | 499 | 464 | 532 | ||

| LLDPE:PP:PVC(3:2:1) | 10 | Stage 1 | –0.23 | 305 | 305 | 376 |

| Stage 2 | –2.58 | 479 | 376 | 507 | ||

| 30 | Stage 1 | –0.18 | 342 | 324 | 396 | |

| Stage 2 | –2.29 | 500 | 396 | 532 | ||

| 40 | Stage 1 | –0.13 | 348 | 337 | 418 | |

| Stage 2 | –1.95 | 507 | 418 | 540 |

The pyrolysis of LLDPE/PP/PVC (3:2:1) could be divided into two main reaction stages. The first DTGP value of LLDPE/PP/PVC mixture was lower than the PVC pyrolysis while it became higher at the second stage. The first stage was mainly ascribed to the chlorine removal. However, the pyrolysis of LLDPE/PP/PVC (3:2:1) would be mainly characterized by the pyrolysis of LLDPE and PP as the temperature was above 427 °C because of the low PVC (1/6) proportion in the mixture. The initial decomposition temperature (Ti) of polymers followed the order of LLDPE > LLDPE/PP (1:1) > LLDPE/PP (1:2) > PP > LLDPE/PP (1:3) > LLDPE/PP/PVC (3:2:1) > PVC, indicating the highest thermal stability of LLDPE.

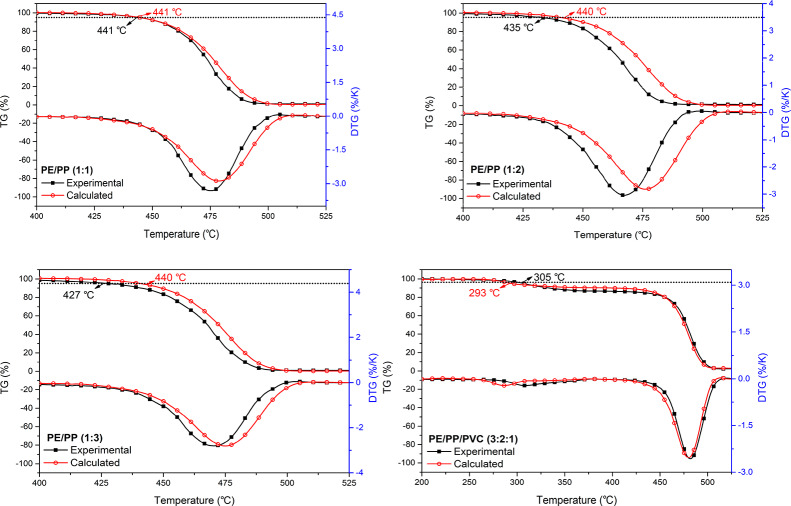

Figure 1 shows the experimental and theoretical TG/DTG curves of the LLDPE/PP (1:1), LLDPE/PP (1:2), LLDPE/PP (1:3), and LLDPE/PP/PVC (3:2:1) pyrolysis under the heating rate of 10 K/min. It is worth pointing out that the theoretical curves were obtained from the linear combination of individual components. The obvious difference could be observed between the experimental and theoretical TG/DTG curves as shown in Figure 1. For LLDPE/PP mixtures, the pyrolysis occurred earlier in practical, implying the promotion of the mixtures pyrolysis. However, the synergistic effect weakened with the increase of LLDPE in the mixtures. At a given temperature, the experimental TG values were lower than that of theoretical calculation. It indicates that the individual components interacted each other during the pyrolysis of LLDPE with PP, which played a synergistic effect on the pyrolysis reaction.

Figure 1.

Experimental and calculated TG/DTG curves of plastic mixture (PE = LLDPE, 10 K/min).

In each case, the peaks of the experimental DTG curves moved to low temperatures compared to the theoretical ones. The corresponding peak values of the experimental DTG curves were higher than that from linear calculation, indicating that the LLDPE/PP mixtures had lower thermal stability during the co-pyrolysis of LLDPE with PP.

For LLDPE/PP/PVC (3:2:1), a higher initial temperature was observed compared to that of theoretical calculation, indicating the postpone of the LLDPE/PP/PVC (3:2:1) pyrolysis. It also suggests that the chlorine release from PVC moved toward higher temperatures. The experimental DTG curves of LLDPE/PP/PVC (3:2:1) pyrolysis showed higher peak temperature as well as lower peak value at the first stage compared to that of calculated ones. This implies that the LLDPE/PP/PVC (3:2:1) had higher thermal stability during the pyrolysis. It could also conclude that the pyrolysis of LLDPE/PP/PVC (3:2:1) led to a deceleration of the chlorine release from PVC. At the second stage, the difference between the experimental and the calculated TG/DTG curves indicated an unnoticeable antagonistic during the LLDPE/PP/PVC (3:2:1) pyrolysis. Besides, the pyrolysis reactions at the second stage were mainly composed of LLDPE with PP decomposition because of the low proportion of PVC in the LLDPE/PP/PVC (3:2:1) mixture. Thus, the co-pyrolysis of LLDPE and PP was hindered after the introduction of PVC.

3.3. Chlorine-Removal Behavior

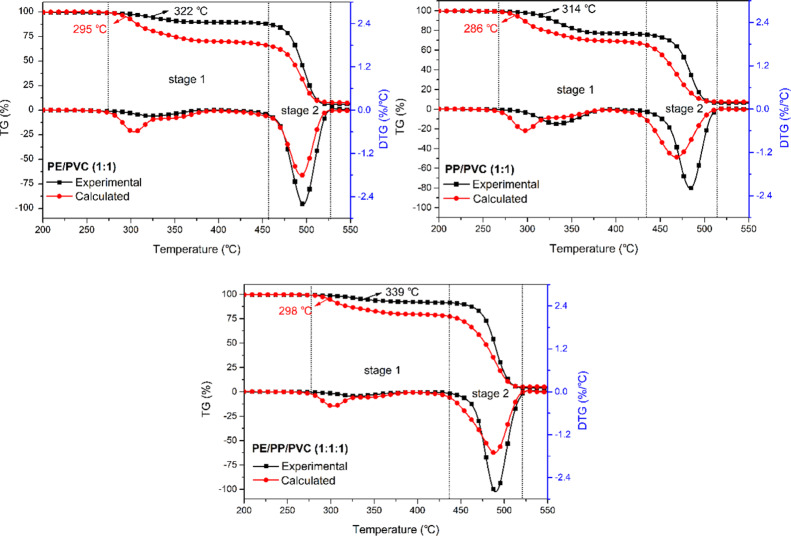

The co-pyrolysis plastic had a significant impact on the behavior of chlorine removal. To further investigate the synergistic effect, the PVC was mixed with LLDPE and PP at various mass ratios and then pyrolyzed under the heating rate of 20 K/min. The experimental and calculated TG/DTG curves are presented in Figure 2. An obvious deviation between the experimental and the theoretical TG/DTG curves was observed for LLDPE/PVC (1:1), PP/PVC (1:1), and LLDPE/PP/PVC (1:1:1), indicating that a strong interaction occurred at the dechlorination stage of the plastic mixture pyrolysis.

Figure 2.

Experimental and theoretical TG/DTG curves of LLDPE/PVC (1:1), PP/PVC (1:1), and LLDPE/PP/PVC (1:1:1) (PE = LLDPE, 20 K/min).

The pyrolysis occurred lately than the theoretical ones for LLDPE/PVC (1:1), PP/PVC (1:1), and LLDPE/PP/PVC (1:1:1), suggesting that the chlorine release was postponed in the pyrolysis. Additionally, the experimental TG values at a given temperature were relatively higher than that of theoretical values in all the cases, indicating an antagonistic effect during the plastic mixture pyrolysis.

Figure 2 shows the higher peak temperature and the lower peak value of the experimental DTG curves at the first stage of the LLDPE/PVC (1:1), PP/PVC (1:1), and LLDPE/PP/PVC (1:1:1) pyrolysis, showing a higher thermal stability of the plastic mixtures. The decomposition of the second stage was slightly delayed in the pyrolysis of plastic mixtures. Tang et al.,23 analyzed the chlorine balance and concluded that about 88–96 wt % of chlorine would be released in the form of HCl, 3–12 wt % stayed in liquid, and only ∼2 wt % in char. Besides, the chlorine content of the liquid products depended on the type of plastic added, suggesting that there were reactions between the products from the PVC degradation and those from the degradation of the other plastics. To some extent, these reactions would promote or hinder the chlorine removal, which could be presented as the variation of the initial decomposition temperature and also the decomposition rate. The results here show that the other plastic would hinder the chlorine removal from chlorinated waste plastics. In other words, the treatment of chlorinated waste plastics became more difficult than that of PVC in thermal conversion, and more attention should be paid on the high-temperature chlorine corrosion in practical.

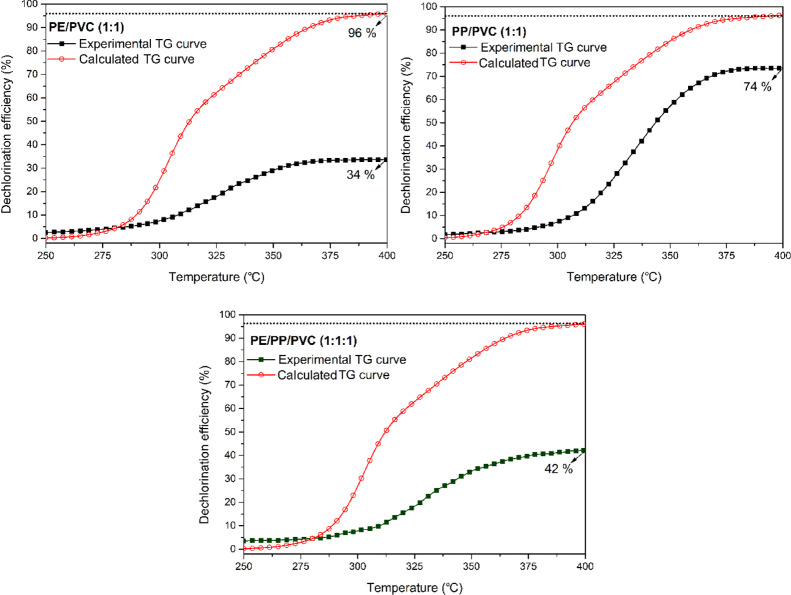

The dechlorination efficiency ψ at the first stage was estimated by ψ = Clrelease/Cltotal based on TG data. The experimental and theoretical dichlorination efficiencies are presented in Figure 3. Both LLDPE/PVC (1:1) and PP/PVC (1:1) showed a lower experimental dechlorination efficiency compared to that of calculated ones. This suggests a noticeable antagonistic effect on dechlorination during the co-pyrolysis of PVC with LLDPE or PP. Similarly, the deviation between the experimental and theoretical dechlorination efficiency also showed an antagonistic effect on dechlorination for LLDPE/PP/PVC (1:1:1). Thus, all these results suggested that the treatment of chlorinated waste plastics was more difficult than that of PVC in thermal conversion.

Figure 3.

Chlorine-removal efficiency of LLDPE/PVC (1:1), PP/PVC (1:1), and LLDPE/PP/PVC (1:1:1) at the first stage of co-pyrolysis (PE = LLDPE, 20 K/min).

3.4. Kinetics Behavior

Figure S2 shows the fitting curves according to eq 5. The corresponding correlation coefficients (R2) are summarized in Table S1. The values of R2 exceeded 0.98 in the all cases, with the exception of PP (0.97) and LLDPE/PP/PVC (3:2:1) (0.96) at the conversion of 0.1. It indicates that the DAEM method could well predict the kinetics behavior of the polymer pyrolysis. The kinetics parameters (E and A) are found in Tables S2 and S3.

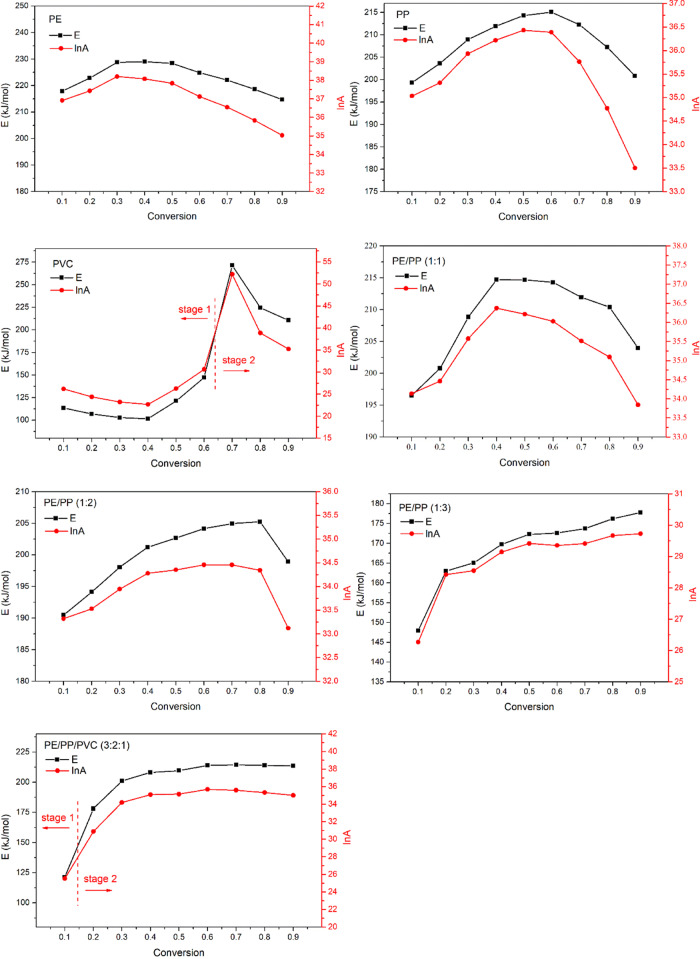

Figure 4 shows the variation of the activation energy (E) and lnA at the conversion range of 0.1–0.9 for LLDPE, PP, PVC, and their mixtures. The activation energy (E) of LLDPE and PP fluctuated in the range of 215–229 and 199–215 kJ/mol, respectively. Unlike LLDPE and PP, PVC showed two reaction stages as dechlorination and depolymerization, which had an activation energy (E) of 102–147 and 211–272 kJ/mol, respectively. The bonding energy of the C–Cl was lower than that of C–C.9 The activation energy (E) of the first stage was lower than that of the second stage, resulting from the unstable structure of PVC at a temperature above 200 °C. The two stages of PVC pyrolysis were corresponding to the breaking of C–Cl and C–C bonds.

Figure 4.

Activation energy (E) and lnA of LLDPE, PP, PVC, and their mixtures within the conversion range of 0.1–0.9 (PE = LLDPE).

For LLDPE/PP mixtures, the activation energy (E) kept reducing with the decrease of the initial mass ratio of LLDPE to PP at the same conversion rate. This was because of the relatively low activation energy of PP. For LLDPE/PP/PVC (3:2:1), the pyrolysis of LLDPE/PP/PVC (3:2:1) was mainly characterized by the pyrolysis of both LLDPE and PP because of their share in the mixture after chlorine removal. Thus, higher activation energy (E) was observed after the conversion rate of 0.1. Additionally, a similar feature of the kinetics behavior was observed for LLDPE, PP, PVC, and their mixtures. The variation of the activation energy (E) showed the same trend as that of lnA. The maximum activation energy (E) as well as lnA was observed at the same conversion rate. It could be explained by the kinetics compensation effect, indicating the linear relationship between the activation entropy of the activated body and the activated enthalpy.24

4. Conclusions

Pyrolysis of plastics (LLDPE, PP, and PVC) and their mixtures was conducted under non-isothermal conditions to investigate the synergistic effect and its impact on chlorine removal from chlorinated plastics. The TGA data clearly indicated the synergistic effect during the pyrolysis of plastic mixtures. The decomposition of the LLDPE/PP mixtures occurred earlier than that of calculated ones. However, the synergistic effect weakened with the increase of LLDPE proportion in the mixtures.

For the mixtures containing PVC, the dechlorination temperature was delayed after introduction of the LLDPE and PP. In the meanwhile, the PVC dechlorination ratio was hindered after introduction of LLDPE or PP. It suggests that the treatment of chlorinated waste plastics was more difficult than that of PVC in thermal conversion. In practical, more attention should be paid on both the high-temperature chlorine corrosion and high-efficient chlorine removal. These data are helpful for the treatment and thermal utilization of the yearly increased plastic wastes.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b04116.

Composition of TG/DTG curves, fitting curves, fitting correlation coefficient value R2, activation energy values, and frequency factor values (PDF)

Author Contributions

P.Z. and Q.G. conceived and designed the experiments; Z.Y. and H.T. performed the experiments; X.C. and L.G. performed theoretical study; Z.W. analyzed the data; P.Z., Z.Y., and J.Z. wrote the paper.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 51706240), the Foundation of State Key Laboratory of High-efficiency Utilization of Coal and Green Chemical Engineering (grant no. 2018-K02), and the China Scholarship Council ([2018]5046, International Clean Energy Talent Program 2018).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- PlasticEurope . Plastics—the Facts 2018: An analysis of European plastics production, demand and waste data. https://www.plasticseurope.org/application/files/6315/4510/9658/Plastics_the_facts_2018_AF_web.pdf (accessed Aug 24, 2019).

- He P.; Chen L.; Shao L.; Zhang H.; Lü F. Municipal solid waste (MSW) landfill: A source of microplastics? -Evidence of microplastics in landfill leachate. Water Res. 2019, 159, 38–45. 10.1016/j.watres.2019.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.; Williams P. T. Pyrolysis–gasification of plastics, mixed plastics and real-world plastic waste with and without Ni–Mg–Al catalyst. Fuel 2010, 89, 3022–3032. 10.1016/j.fuel.2010.05.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R. K.; Ruj B.; Sadhukhan A. K.; Gupta P. Impact of fast and slow pyrolysis on the degradation of mixed plastic waste: Product yield analysis and their characterization. J. Energy Inst. 2019, 92, 1647–1657. 10.1016/j.joei.2019.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tulashie S. K.; Boadu E. K.; Dapaah S. Plastic waste to fuel via pyrolysis: A key way to solving the severe plastic waste problem in Ghana. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2019, 11, 417–424. 10.1016/j.tsep.2019.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharuddin S. D. A.; Abnisa F.; Daud W. M. A. M.; Aroua M. K. A review on pyrolysis of plastic wastes. Energy Convers. Manage. 2016, 115, 308–326. 10.1016/j.enconman.2016.02.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai S.; Yoshioka T. Feedstock Recycling via Waste Plastic Pyrolysis. J. Jpn. Pet. Inst. 2016, 59, 243–253. 10.1627/jpi.59.243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R.; Pakdel H.; Roy C.; Vasile C. Vacuum pyrolysis of commingled plastics containing PVC II. Product analysis. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2001, 73, 47–67. 10.1016/s0141-3910(01)00066-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Chen T.; Luo X.; Han D.; Wang Z.; Wu J. TG/FTIR analysis on co-pyrolysis behavior of PE, PVC and PS. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 676–682. 10.1016/j.wasman.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aboulkas A.; El harfi K.; El Bouadili A. Thermal degradation behaviors of polyethylene and polypropylene. Part I: Pyrolysis kinetics and mechanisms. Energy Convers. Manage. 2010, 51, 1363–1369. 10.1016/j.enconman.2009.12.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F.; Wang B.; Yang D.; Hao J.; Qiao Y.; Tian Y. Thermal degradation of typical plastics under high heating rate conditions by TG-FTIR: Pyrolysis behaviors and kinetic analysis. Energy Convers. Manage. 2018, 171, 1106–1115. 10.1016/j.enconman.2018.06.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Y.; Xu F.; Xu S.; Yang D.; Wang B.; Ming X.; Hao J.; Tian Y. Pyrolysis Characteristics and Kinetics of Typical Municipal Solid Waste Components and Their Mixture: Analytical TG-FTIR Study. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 10801–10812. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.8b02571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soria-Verdugo A.; Goos E.; García-Hernando N.; Riedel U. Analyzing the pyrolysis kinetics of several microalgae species by various differential and integral isoconversional kinetic methods and the Distributed Activation Energy Model. Algal Res. 2018, 32, 11–29. 10.1016/j.algal.2018.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams P. T.; Slaney E. Analysis of products from the pyrolysis and liquefaction of single plastics and waste plastic mixtures. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2007, 51, 754–769. 10.1016/j.resconrec.2006.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams P. T.; Williams E. A. Interaction of Plastics in Mixed-Plastics Pyrolysis. Energy Fuels 1999, 13, 188–196. 10.1021/ef980163x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Filippis P. D.; Caprariis B.; Scarsella M.; Verdone N. Double Distribution Activation Energy Model as Suitable Tool in Explaining Biomass and Coal Pyrolysis Behavior. Energies 2015, 8, 1730–1744. 10.3390/en8031730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. B.; Ma X. B.; Chen D. Z.; Zhao L. Co-pyrolysis characteristics and kinetics analysis of typical waste plastics. Proceedings of the CSEE 2010, 30, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Wang L.; Sun D. C.; Lu X. Study on pyrolysis of low density polyethylene. J. Solid Rocket Technol. 2006, 29, 443–445. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G.; Chen D.; Yin L.; Wang Z.; Zhao L.; Wang J. Y. High efficiency chlorine removal from polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pyrolysis with a gas–liquid fluidized bed reactor. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 1045–1050. 10.1016/j.wasman.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López A.; de Marco I.; Caballero B. M.; Laresgoiti M. F.; Adrados A. Dechlorination of fuels in pyrolysis of PVC containing plastic wastes. Fuel Process. Technol. 2011, 92, 253–260. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2010.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y. Y.; Xie K. C. Application of Py/FTIR to pyrolysis of PVC. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2002, 30, 569–572. [Google Scholar]

- Yu J.; Sun L.; Ma C.; Qiao Y.; Yao H. Thermal degradation of PVC: A review. Waste Manag. 2016, 48, 300–314. 10.1016/j.wasman.2015.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y.; Huang Q.; Sun K.; Chi Y.; Yan J. Co-pyrolysis characteristics and kinetics analysis of organic food waste and plastic. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 249, 16–23. 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.09.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley J.; Siriwardane R.; Tian H.; Benincosa W.; Poston J. Kinetic analysis of the interactions between calcium ferrite and coal char for chemical looping gasification applications: Identifying reduction routes and modes of oxygen transfer. Appl. Energy 2017, 201, 94–110. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.05.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.