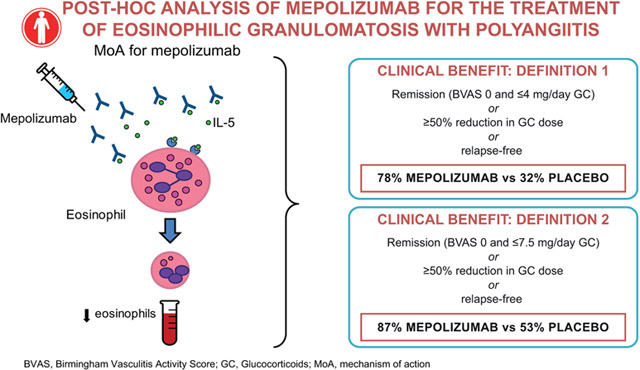

Abstract

Background:

In a recent phase III trial (NCT02020889), 53% of mepolizumab-treated, versus 19% of placebo-treated patients with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) achieved protocol-defined remission.

Objective:

To investigate post hoc the clinical benefit of mepolizumab in patients with EGPA, using a comprehensive definition of benefit encompassing remission, oral glucocorticoid (OGC) dose reduction, and EGPA relapses.

Methods:

The randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group trial recruited patients with relapsing/refractory EGPA receiving stable OGC (prednisolone/prednisone, ≥7.5–50mg/day) for ≥4 weeks. Patients received 300mg subcutaneous mepolizumab or placebo every 4 weeks for 52 weeks. Clinical benefit was defined post hoc as: remission at any time (two definitions used); or ≥50% OGC dose reduction during Weeks 48–52; or no EGPA relapses. The two remission definitions were Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score [BVAS]=0 plus OGC dose ≤4mg/day (remission1/clinical benefit1) or ≤7.5mg/day (remission2/clinical benefit2). Clinical benefit was assessed in all patients, and among subgroups with: baseline blood eosinophil counts[BEC] <150cells/μL; baseline OGC >20mg/day; or, weight >85kg.

Results:

With mepolizumab versus placebo, 78% versus 32% of patients experienced clinical benefit1, and 87% versus 53% of patients experienced clinical benefit2 (both p<0.001). Significantly more patients experienced clinical benefit1 with mepolizumab versus placebo in the BEC <150cells/μL subgroup (72% versus 43%, p=0.033) and weight >85kg subgroup (68% versus 23%, p=0.005); in the OGC >20mg/day subgroup results were not significant but favored mepolizumab (60% versus 36%, p=0.395).

Conclusion:

When a comprehensive definition of clinical benefit was applied to data from a randomized controlled trial, 78%–87% of patients with EGPA experienced benefit with mepolizumab.

Keywords: Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Churg-Strauss syndrome, mepolizumab, eosinophils, interleukin-5, vasculitis

Graphical Abstract

Capsule Summary

This post hoc assessment of a recent clinical trial of mepolizumab in patients with EGPA demonstrates that patients not achieving protocol-defined remission still met important clinical endpoints of remission, glucocorticoid dose reduction and no relapses.

Introduction

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), previously known as Churg-Strauss, is a rare, multisystem disease characterized by asthma, sinusitis, blood and tissue eosinophilia, and systemic necrotizing vasculitis (1, 2). The precise role of eosinophils in the pathology of EGPA remains unclear; however, evidence of blood eosinophilia, eosinophilic tissue infiltration of the lungs, heart, and gastrointestinal tract, and vascular and extravascular eosinophilic granulomatous inflammation, suggest that eosinophils are central to EGPA pathogenesis (1-5).

Glucocorticoids reduce blood and tissue eosinophil counts by inducing apoptosis and inhibiting prosurvival signaling pathways (6). Based on long-term studies showing increased patient survival, oral glucocorticoids are currently recommended as first-line treatment for EGPA (7). However, relapses frequently occur and many patients fail to taper their oral glucocorticoid dose or discontinue oral glucocorticoid treatment (6, 8, 9). Chronic and high-dose oral glucocorticoid use is associated with serious and sometimes irreversible adverse effects, including increased risk of infection, osteoporosis, and secondary adrenal insufficiency (10, 11). Even short courses of high-dose oral glucocorticoids are associated with side effects (12). Immunosuppressive therapy is also recommended for remission-induction and as maintenance therapy in EGPA (7). Although oral glucocorticoid and immunosuppressive therapies are commonly used (13), they have not been systematically investigated in controlled trials for EGPA. Furthermore, expert opinion and small studies suggest that use of immunosuppressive agents does not substantially affect relapse rates (14). Considering the inadequate efficacy of oral glucocorticoids in inducing relapse-free remission and the significant side-effect burden associated with both oral glucocorticoids and other immunosuppressive drugs, there is a pressing need for more effective and tolerable treatment options for EGPA.

Mepolizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 monoclonal antibody that reduces blood and airway eosinophils (3, 5), has been investigated as a potential therapy for patients with EGPA (15-17). A phase III trial was recently conducted to assess the efficacy and safety of mepolizumab in patients with relapsing and refractory EGPA over 52 weeks (5). The trial assessed two primary endpoints: total accrued weeks of remission (defined as Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score [BVAS]=0 and oral glucocorticoid dose ≤4 mg/day), and the proportion of patients who achieved remission at Weeks 36 and 48. Overall, 28% of patients receiving mepolizumab, versus 3% of patients receiving placebo, experienced ≤24 weeks of accrued remission; 32% versus 3%, respectively, had remission at both Weeks 36 and 48. Although both primary endpoints were met, many patients in the mepolizumab treatment group did not achieve protocol-defined remission. However, it is further hypothesized that treatment with mepolizumab provided clinical benefits that were not encompassed by the trial’s pre-defined remission endpoints.

There are several aspects of clinical benefit aside from protocol-defined remission that are important to consider when assessing the efficacy of therapy in EGPA. As such, determining the impact of mepolizumab treatment on clinical parameters additional to the primary and secondary endpoints of the phase III trial is of relevance to clinicians and patients with EGPA. The objective of this post hoc assessment was to gain a broader overview of the efficacy of mepolizumab in EGPA by investigating whether further clinical benefits, additional to those demonstrated in the original analysis, were present. To do this, patient response was assessed using a composite definition of clinical benefit that was based on the three objectives of treatment: remission, oral glucocorticoid dose reduction, and a reduction in the rate of relapses.

Methods

Study design and treatments

The study design and treatment schedule of the phase III trial (GSK ID 115921(18); NCT02020889) have been reported previously (5). In brief, the study was a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group, multicenter trial. After screening, which occurred 1–4 weeks prior to baseline, patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive 300 mg of subcutaneous mepolizumab (GlaxoSmithKline, Philadelphia, US) or placebo, in addition to standard of care, every 4 weeks for 52 weeks (final dose at Week 48). This was followed by an 8-week follow-up period. Patients’ oral glucocorticoid dose had to remain stable from the initiation of screening (Week −4) to Week 4, but thereafter could be reduced by the investigator with a recommended tapering schedule.

Patients

To be enrolled in the study, patients had to be ≥18 years of age, diagnosed with relapsing or refractory EGPA at least 6 months previously, and receiving a stable dose of oral glucocorticoids (prednisolone or prednisone, ≥7.5–≤50 mg/day), with or without additional immunosuppressive therapy, for ≤4 weeks prior to enrollment in the study. Further details of participant selection criteria are detailed in the primary publication (5). The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and any applicable country-specific requirements. All participants provided written informed consent. The original study was approved by each local institutional review board.

Post hoc assessments and endpoints

Clinical benefit was a composite endpoint which was met if patients met at least one of the following three component endpoints, which were all pre-defined in the original study: (1) remission at any time during the study period (Weeks 1–52) or, (2) a ≥50% reduction in oral glucocorticoid dose during Weeks 48–52 or, (3) no relapses of EGPA during the study period (Weeks 1–52). As in the original study, remission was defined using two separate criteria: firstly, a BVAS of 0 plus an oral glucocorticoid dose ≤4 mg/day (remission1), and secondly, an alternative definition based on the European League against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for clinical studies in systemic vasculitis (BVAS of 0 plus an oral glucocorticoid dose ≤7.5 mg/day [remission2]) (19). Clinical benefit, therefore, was defined as either clinical benefit1, when encompassing the criteria for remission1, or clinical benefit2, when encompassing the criteria for remission2. A relapse of EGPA was defined as active vasculitis (BVAS >0), or active asthma symptoms with a corresponding worsening score in the Asthma Control Questionnaire-6, or worsening sino-nasal symptoms requiring an increase in oral glucocorticoid dose to >4.0 mg per day, an initiation or increase of immunosuppressive therapy, or hospitalization.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the proportion (n and % of total) of patients to meet each definition of clinical benefit. Analyses were performed using the as-treated population. Statistical analyses of treatment response for mepolizumab versus placebo were performed using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test.

Subgroups of clinical interest

Endpoints were also assessed in specific subgroups of clinical interest, including baseline blood eosinophil count <150 cells/μL and baseline oral glucocorticoid dose >20 mg/day. Response to mepolizumab, in terms of accrued duration of remission, has previously been reported to be lower in these patient populations than in the general EGPA population (5, 20). The subgroup of patients with weight >85 kg was also investigated as weight is the only patient characteristic that has been associated with pharmacokinetic exposure for this biologic (21).

Results

Patient population

Of the 151 patients enrolled in the phase III study, 136 underwent randomization; 68 were randomly assigned to receive mepolizumab, and 68 to receive placebo. All patients were included in the current analysis. As one patient randomized to placebo received mepolizumab and another patient randomized to mepolizumab received placebo, analyses were carried out using as-treated treatment group allocations, rather than randomized treatment assignments. Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of patient demographic characteristics and diagnostic and baseline characteristics of EGPA (as-treated population).

| Characteristic | All patients (N=136) |

Blood eosinophil count <150 cells/μL (N=57) |

Blood eosinophil count ≥150 cells/μL (N=79) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 48.5 (13.3) | 50.4 (12.8) | 47.1 (13.6) |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 56 (41) | 28 (49) | 28 (35) |

| ANCA-positive status, n (%)1 | 13 (10) | 5 (9) | 8 (10) |

| BVAS >0, n (%)2 | 85 (63) | 35 (61) | 50 (63) |

| Immunosuppressive therapy at baseline, n (%) | 72 (53) | 34 (60) | 38 (48) |

| Presence of EGPA diagnostic disease characteristics at any time during disease course, n (%) | |||

| Asthma with eosinophilia | 136 (100) | 57 (100) | 79 (100) |

| Biopsy evidence3 | 56 (41) | 22 (39) | 34 (43) |

| Neuropathy4 | 56 (41) | 23 (40) | 33 (42) |

| Nonfixed pulmonary infiltrates | 98 (72) | 43 (75) | 55 (70) |

| Sino-nasal abnormality | 128 (94) | 55 (96) | 73 (92) |

| Cardiomyopathy5 | 20 (15) | 9 (16) | 11 (14) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 1 (<1) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Alveolar hemorrhage | 4 (3) | 1 (2) | 3 (4) |

| Palpable purpura | 17 (13) | 4 (7) | 13 (16) |

| ANCA-positive | 26 (19) | 12 (21) | 14 (18) |

| Relapsing disease, n (%) | 100 (74) | 45 (79) | 55 (70) |

| Refractory disease, n (%) | 74 (54) | 28 (49) | 46 (58) |

| Duration since diagnosis of EGPA, year, mean (SD) | 5.5 (4.6) | 6.1 (5.0) | 5.2 (4.3) |

| Immunosuppressive therapy since diagnosis, n (%) | 105 (77) | 45 (79) | 60 (76) |

| Baseline OGC dose, n (%) | |||

| ≤7.5 mg/day | 18 (13) | 5 (9) | 13 (16) |

| >7.5 to ≤12 mg/day | 55 (40) | 16 (28) | 39 (49) |

| >12 to ≤20 mg/day | 42 (31) | 21 (37) | 21 (27) |

| >20 mg/day | 21 (15) | 15 (26) | 6 (8) |

Positive ANCA status for myeloperoxidase or proteinase 3 was assessed at screening by means of immunoassay performed at the Covance laboratory and Q2 Solutions;

The BVAS was assessed on a scale of 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating greater disease activity

Biopsy evidence was defined as a biopsy specimen showing histopathological evidence of eosinophilic vasculitis, perivascular eosinophilic infiltration, or eosinophil-rich granulomatous inflammation

Neuropathy was defined as a mononeuropathy or polyneuropathy (motor deficit or nerve-conduction abnormality)

The presence of cardiomyopathy was established by means of echocardiography or magnetic resonance imaging.

ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; BVAS, Birmingham Vasculitis Score; EGPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; OGC, oral glucocorticoid.

Efficacy within the as-treated population

Composite endpoint

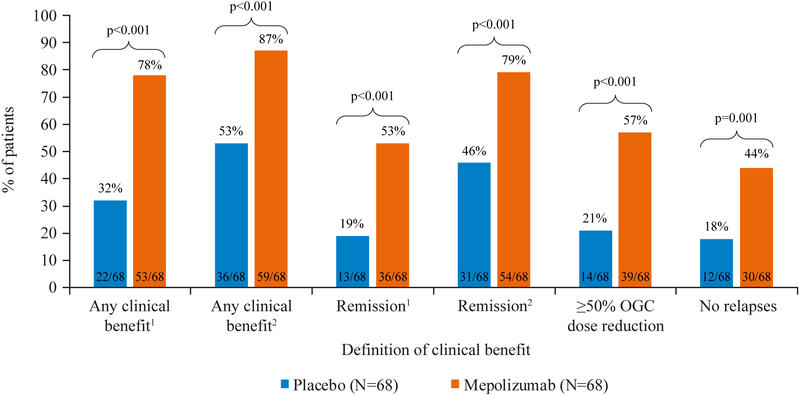

Using the composite endpoint, the proportion of patients experiencing any clinical benefit following treatment with mepolizumab ranged from 78%−87% depending on the remission criteria used (Figure 1), compared with 32%−53% of patients receiving with placebo.

Figure 1.

Summary of clinical benefit following treatment with placebo or mepolizumab (as-treated population).

Clinical benefit was defined as: clinical benefit1 (remission1 at any time during the study treatment period, or ≥50% reduction in average OGC dose during Weeks 48–52, or no EGPA relapses during the study period), or clinical benefit2 (remission2 at any time during the study treatment period, or ≥50% reduction in average OGC dose during Weeks 48–52, or no EGPA relapses during the study period).

1Remission criteria: BVAS=0 plus OGC dose ≤4 mg/day; 2Remission criteria: BVAS=0, OGC dose ≤7.5 mg/day.

BVAS; Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score; OGC, oral glucocorticoid.

When remission was defined as BVAS=0 plus oral glucocorticoid dose ≤4 mg/day (remission1) at any time during the study period, 78% (53/68) of patients in the mepolizumab group compared with 32% (22/68) in the placebo group experienced clinical benefit1 (p<0.001; Figure 1A).

When the definition of clinical benefit included the EULAR remission criteria of BVAS=0 plus oral glucocorticoid dose ≤7.5 mg/day (remission2), the proportion of patients experiencing clinical benefit2 was 87% (59/68) in the mepolizumab group versus 53% (36/68) in the placebo group (p<0.001; Figure 1B). This increase in the proportion of patients experiencing clinical benefit was driven by an increase to 79% (54/68) of patients in the mepolizumab group and 46% (31/68) of patients in the placebo group achieving EULAR-defined remission during the study period.

Individual components of the composite endpoint

When assessing the individual components from the composite endpoint, 53% (36/68) of patients receiving mepolizumab achieved remission1 (BVAS=0 plus oral glucocorticoid dose ≤4 mg/day) at any time during the study period compared with 19% (13/68) of patients receiving placebo (p<0.001). Additionally, 57% (39/68) of patients receiving mepolizumab were able to reduce their oral glucocorticoid dose by ≥50%, compared with 21% (14/68) of patients on placebo (p<0.001), and 44% (30/68) of patients receiving mepolizumab were relapse-free versus 18% (12/68) of patients receiving placebo (p=0.001; Figure 1A).

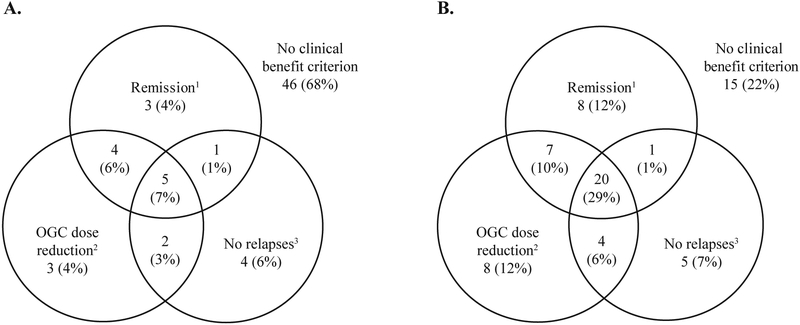

Combinations of components included in the composite endpoint

In addition to assessing the proportion of patients that met the composite endpoint, a more detailed analysis was conducted of the proportion of patients that met each combination of component endpoints (Figure 2). Overall, 29% (20/68) of patients in the mepolizumab group met all three definitions of clinical benefit1 (remission1 at any time [BVAS=0, plus oral glucocorticoid dose ≤4 mg/day], plus ≥50% oral glucocorticoid dose reduction, plus no EGPA relapses) compared with only 7% (5/68) of patients in the placebo group (Figure 2). Notably, 25% (17/68) of patients receiving mepolizumab, versus 13% (9/68) of patients receiving placebo, achieved a ≥50% reduction in oral glucocorticoid dose, no EGPA relapses, or both, despite not achieving remission1 (BVAS=0, plus oral glucocorticoid dose ≤4 mg/day). Fifteen (22%) patients receiving mepolizumab were unable to meet any of the three components of clinical benefit, compared with 46 (68%) of patients receiving placebo (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of the proportion of patients receiving A. placebo (N=68) and B. mepolizumab (N=68) to meet each definition of clinical benefit.

1Remission category BVAS=0 and OGC dose ≤4 mg/day during the study treatment period; 2≥50% reduction in average OGC dose during Weeks 48–52; 3No EGPA relapses during the study treatment period.

BVAS; Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score; OGC, oral glucocorticoid.

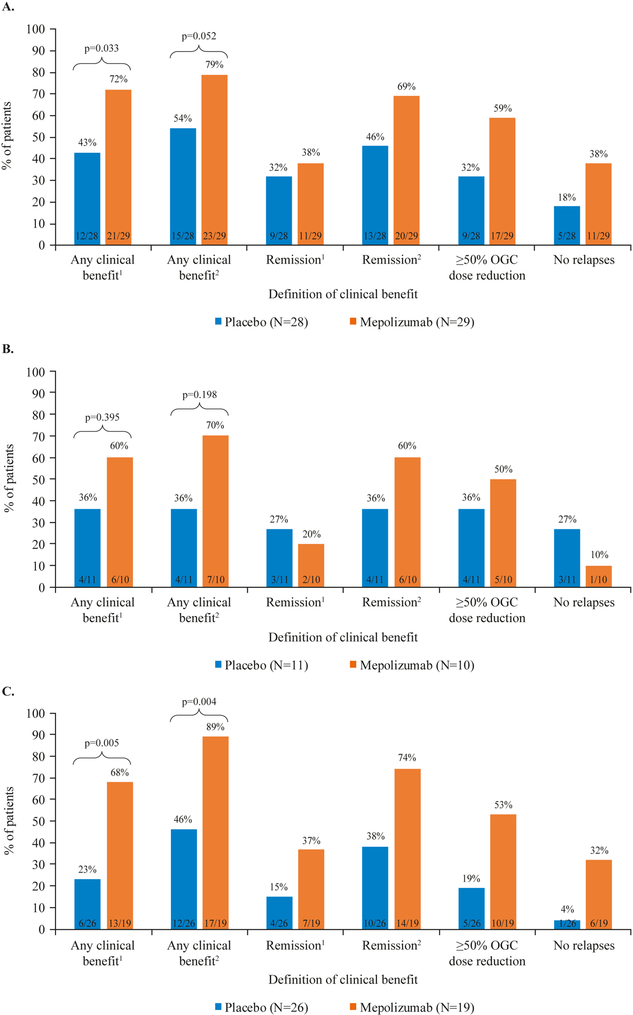

Efficacy within selected clinical subgroups

Baseline blood eosinophil count

For patients with baseline blood eosinophil counts <150 cells/μL, there was evidence of clinical benefit from treatment with mepolizumab. When clinical benefit included remission1 (BVAS=0 plus oral glucocorticoid ≤4 mg/day), patients in this subgroup receiving mepolizumab experienced significantly greater clinical benefit than patients receiving placebo; overall, 72% (21/29) of patients receiving mepolizumab experienced clinical benefit1, compared with 43% (12/28) of patients receiving placebo (p=0.033; Figure 3A). When clinical benefit included remission2 (BVAS=0 plus oral glucocorticoid dose ≤7.5 mg/day), the increase in clinical benefit observed among patients receiving mepolizumab versus patients receiving placebo was not significant at the 5% level, but was directionally in favor of mepolizumab; 79% (23/29) of patients receiving mepolizumab experienced clinical benefit2, compared with 54% (15/28) of patients receiving placebo (p=0.052; Figure 4A).

Figure 3.

Summary of clinical benefit in A. baseline blood eosinophil count <150 cells/μL subgroup (N=57), B. baseline OGC dose >20 mg/day subgroup (N=21), and C. weight >85 kg subgroup (N=45).

Clinical benefit was defined as: clinical benefit1 (remission1 at any time during the study treatment period, or ≥50% reduction in average OGC dose during Weeks 48–52, or no EGPA relapses during the study period), or clinical benefit2 (remission2 at any time during the study treatment period, or ≥50% reduction in average OGC dose during Weeks 48–52, or no EGPA relapses during the study period).

1Remission criteria: BVAS=0 plus OGC dose ≤4 mg/day; 2Remission criteria: BVAS=0, OGC dose ≤7.5 mg/day.

BVAS; Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score; EGPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; OGC, oral glucocorticoid.

Oral glucocorticoid dose

For patients with baseline oral glucocorticoid dose >20 mg/day, treatment with mepolizumab did not lead to a significant increase in clinical benefit compared to treatment with placebo; however, results were directionally in favor of mepolizumab compared with placebo. When clinical benefit included remission1 (BVAS=0 plus oral glucocorticoid dose ≤4 mg/day), 60% (6/10) patients in the mepolizumab treatment group experienced clinical benefit1 compared with 36% (4/11) of patients in the placebo group (p=0.359; Figure 3B). When clinical benefit included remission2, 70% (7/10) patients in the mepolizumab treatment group compared with 36% (4/11) of patients in the placebo group experienced clinical benefit2 (p=0.198; Figure 4B).

Baseline weight

Within the subgroup of patients with baseline weight >85 kg, mepolizumab provided greater clinical benefit than placebo for both definitions of clinical benefit. When clinical benefit included the remission definition BVAS=0 plus oral glucocorticoid dose <4 mg/day (remission1), 68% (13/19) of patients receiving mepolizumab experienced clinical benefit1, compared with 23% (6/26) of patients receiving placebo (p=0.005; Figure 3C). When clinical benefit included the EULAR remission criteria (remission2), 89% (17/19) of patients receiving mepolizumab experienced clinical benefit2, compared with 46% (12/26) of patients receiving placebo (p=0.004; Figure 4C).

Discussion

These post hoc analyses provide a broader overview of the efficacy of mepolizumab in patients with relapsing or refractory EGPA using data from the recent phase III trial (5). Results from this analysis show that more patients treated with mepolizumab versus patients treated with placebo experienced clinical benefit according to the composite endpoint used. This endpoint incorporated the pre-defined primary endpoint from the phase III trial (remission [BVAS=0 plus oral glucocorticoid dose ≤4 mg/day] at any time during Weeks 1–52), or remission as defined by the EULAR remission criteria (BVAS=0 plus oral glucocorticoid dose ≤7.5 mg/day), as well as two additional pre-defined, clinically relevant endpoints from the trial (≤50% reduction in oral glucocorticoid dose during Weeks 48–52, and no relapses of EGPA during Weeks 1–52), with the aim of further assessing clinical responses that are meaningful for healthcare providers and patients with EGPA. The primary endpoint in the phase III clinical trial, total accrued time of remission (5), was developed with the FDA for regulatory purposes, and was designed to capture a meaningful difference due to treatment in a condition with frequent relapses. What is notable here is that patients also experienced additional forms of clinical benefit that had a substantial influence on their experience of disease, such as a lack of EGPA relapse or a reduction in oral glucocorticoid dose. By using a broader, but still clinically relevant definition of clinical benefit, these assessments provide additional insight into patient responses to treatment with mepolizumab.

There are many reasons why a patient may have been able to meet one definition of clinical benefit but not another, depending on the specific nature of their disease. In particular, an oral glucocorticoid dose of ≤4 mg/day (required to meet protocol-defined remission) would have been difficult to achieve for patients with a high burden of disease who entered the study on a dose >20 mg/day. However, results from the current assessments show that patients who did not achieve remission may have experienced other forms of clinical benefit, such as having a ≥50% decrease in daily oral glucocorticoid dose compared with baseline and being relapse-free (exacerbation-free) throughout the study period.

There was a relatively high response rate in the placebo group (up to 53%) when using the definition of clinical benefit that used either remission criteria. This may indicate that many patients were on higher oral glucocorticoid doses than necessary at baseline, and highlights the importance of optimizing patients’ oral glucocorticoid doses in clinical practice.

Overall, among patients with baseline blood eosinophil counts <150 cells/μL, a greater proportion of patients experienced clinical benefit with mepolizumab versus placebo. In this subgroup, higher proportions of patients receiving mepolizumab achieved ≥50% reduction in oral glucocorticoid dose during Weeks 48–52 and were relapse-free during the treatment period compared with patients receiving placebo. For clinical benefit1 (remission criteria1: BVAS=0, oral glucocorticoid ≤4 mg/day), but not clinical benefit2 (remission criteria2: BVAS=0, oral glucocorticoid ≤7.5 mg/day), a significantly greater proportion of patients receiving mepolizumab experienced any clinical benefit compared with patients receiving placebo. Of note, patients with blood eosinophil count <150 cells/μL more commonly had a higher baseline oral glucocorticoid dose (Table 1), making it harder for them to achieve protocol-defined remission while following the recommended tapering schedule. This may partially explain why mepolizumab has previously been associated with a lower accrued duration of remission in patients with a blood eosinophil count <150 cells/μL compared with patients with a blood eosinophil count ≥150 cells/μL (5, 20). In the subgroup of patients with a baseline oral glucocorticoid dose >20 mg/day, results for the individual components of the composite endpoint were not consistent; however, the proportions of patients to experience any clinical benefit1 and clinical benefit2 were higher among patients treated with mepolizumab versus patients treated with placebo (not significant). Additionally, in the subgroup of patients with weight >85 kg, significantly greater proportions of patients treated with mepolizumab versus patients treated with placebo experienced clinical benefit1 and clinical benefit2.

Other studies that have investigated the use of mepolizumab for the treatment of EGPA have also reported on the ability of mepolizumab to induce remission, prevent relapses, and allow a reduction in glucocorticoid dose (15, 17). In a pilot study of mepolizumab in patients with EGPA (15), the glucocorticoid-sparing effect of mepolizumab was investigated as a primary endpoint. A 64% reduction in mean oral glucocorticoid dose, from 12.9 mg/day at baseline, to 4.6 mg/day after 12 weeks of therapy (p<0.001) was observed. Additionally, in a phase II trial of mepolizumab (17), 80% (8/10) of patients achieved remission (EULAR remission criteria) at Week 32, 100% (10/10) of patients experienced no EGPA relapses during treatment and the median daily glucocorticoid dose was reduced from a 19 mg at baseline to 4 mg at Week 32 (p=0.006). The glucocorticoid-sparing effect of mepolizumab is also supported by the results of the recent phase III trial (5). During Weeks 48–52, 44% (30/68) pf patients receiving mepolizumab versus 7% (5/68) of patients receiving placebo were able to taper their oral glucocorticoid dose to ≤4 mg/day, and 18% (12/68) versus 3% (2/68), respectively, were able to discontinue oral glucocorticoid completely (5). These results support the concept that clinical response to mepolizumab in patients with EGPA extends beyond remission, and encompasses other benefits including a decrease in daily oral glucocorticoid dose, with the potential for a reduction in the dose-related side effects. Further work is currently underway to identify biomarkers that can predict disease activity or relapse in EGPA and may help to identify those patients who may be more responsive to treatment.

This analysis had several limitations. First, the number of patients in the baseline oral glucocorticoid dose >20 mg/day subgroup was low (n=21), therefore caution should be taken when interpreting the results for this particular subgroup. Secondly, due to the ability of oral glucocorticoid to suppress blood eosinophil counts, patients with higher baseline oral glucocorticoid doses would have been more likely to have lower baseline blood eosinophil counts. As such, there was considerable correlation between the baseline oral glucocorticoid dose >20 mg/day and baseline eosinophil count <150 cells/μL subgroups.

This assessment of the recent mepolizumab phase III clinical trial (5) investigated a broader definition of clinical benefit to help classify and assess treatment response in patients with relapsing or refractory EGPA. The results presented here show that treatment with mepolizumab provides clinical benefit by allowing a reduction in oral glucocorticoid dose in most patients. Additionally, patients experienced clinical benefit through a decrease in the number of relapses of EGPA, which, even in the absence of remission, means that patients are subject to fewer increases in glucocorticoid dose to manage their disease. Overall, the analyses performed in this study provide insights that are complementary to that of the phase III primary endpoint assessment and identify clinical responses to mepolizumab that are meaningful to both patients and providers.

Clinical Implications.

Mepolizumab provides clinical benefit in terms of remission, glucocorticoid dose reduction and reduced relapses in patients with relapsing or refractory eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA).

Acknowledgments

The primary study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK ID 115921; NCT02020889) and the NIH NIAID (U01 AI097073). The post hoc, secondary analysis of 115921 presented in this paper was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

Editorial support (in the form of writing assistance, including development of the initial draft, assembling tables and figures, collating authors comments, grammatical editing, and referencing) was provided by Natasha Dean, MSc, and Elizabeth Hutchinson, PhD, CMPP, at Fishawack Indicia Ltd, UK, and was funded by GSK.

Funding sources and role: This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK ID 115921 ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT02020889), the NIH NIAID (U01 AI097073) and in part by the Division of Intramural Research, NIAID, NIH. The post hoc analysis of 115921/ NCT02020889 presented in this paper was funded by GlaxoSmithKline. All authors had roles in the conception, design, and interpretation of the analysis. All authors participated in the development of the manuscript and had access to the data from the study. The decision to submit for publication was that of the authors alone. The sponsor did not place any restrictions on access to the data or on the statements made in the manuscript. The corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Abbreviations

- ANCA

antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

- BVAS

Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score

- EGPA

eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- EULAR

European League against Rheumatism

- OGC

oral glucocorticoid

- SD

standard deviation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

JS, ESB, JB, SM, and SWY are employees of GSK and own stocks in GSK. PA has received research grants from GSK and the NIH, and has acted as a consultant for Ambrx, GSK, and AstraZeneca. MCC has acted as a consultant for GSK, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Abbvie and Roche. GJG has received research grants from the NIH, and has acted as a consultant for Genentech. DJ has received research grants from GSK and acted as a consultant for GSK. CAL has received research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, ChemoCentryx, and GSK and is a non-paid consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb and Abbvie. PAM has received research funds and/or consulting fees from Abbvie, Actelion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myears Squibb, Celgene, ChemoCentryx, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, InflaRx, Insmed, Kypha, TerumoBCT. FM has received research grants from Roche and has acted as a consultant for Chugai, GSK, Lily, and Roche. MEW has acted as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Genentech, GSK, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sentien, Teva, and Vectura, and has received research funding from Teva, AstraZeneca, Novartis and Sanofi. PFW has received research grants from NIH and acted as a consultant for GSK. PK and US have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References:

- 1.Gioffredi A, Maritati F, Oliva E, Buzio C. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: an overview. Front Immunol. 2014;5:549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khoury P, Grayson PC, Klion AD. Eosinophils in vasculitis: characteristics and roles in pathogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(8):474–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukherjee M, Sehmi R, Nair P. Anti-IL5 therapy for asthma and beyond. World Allergy Organ J. 2014;7(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaglio A, Buzio C, Zwerina J. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss): state of the art. Allergy. 2013;68(3):261–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wechsler ME, Akuthota P, Jayne D, Khoury P, Klion A, Langford CA, et al. Mepolizumab or Placebo for Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(20):1921–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fulkerson PC, Rothenberg ME. Targeting eosinophils in allergy, inflammation and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(2):117–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groh M, Pagnoux C, Baldini C, Bel E, Bottero P, Cottin V, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) (EGPA) Consensus Task Force recommendations for evaluation and management. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26(7):545–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Comarmond C, Pagnoux C, Khellaf M, Cordier JF, Hamidou M, Viallard JF, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss): clinical characteristics and long-term followup of the 383 patients enrolled in the French Vasculitis Study Group cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):270–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samson M, Puechal X, Devilliers H, Ribi C, Cohen P, Stern M, et al. Long-term outcomes of 118 patients with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss syndrome) enrolled in two prospective trials. J Autoimmun. 2013;43:60–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daugherty J, Lin X, Baxter R, Suruki R, Bradford E. The impact of long-term systemic glucocorticoid use in severe asthma: A UK retrospective cohort analysis. J Asthma. 2017:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strehl C, Bijlsma JW, de Wit M, Boers M, Caeyers N, Cutolo M, et al. Defining conditions where long-term glucocorticoid treatment has an acceptably low level of harm to facilitate implementation of existing recommendations: viewpoints from an EULAR task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(6):952–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchman AL. Side effects of corticosteroid therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33(4):289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moosig F, Bremer JP, Hellmich B, Holle JU, Holl-Ulrich K, Laudien M, et al. A vasculitis centre based management strategy leads to improved outcome in eosinophilic granulomatosis and polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss, EGPA): monocentric experiences in 150 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(6):1011–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puechal X, Pagnoux C, Baron G, Quemeneur T, Neel A, Agard C, et al. Adding Azathioprine to Remission-Induction Glucocorticoids for Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss), Microscopic Polyangiitis, or Polyarteritis Nodosa Without Poor Prognosis Factors: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(11):2175–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim S, Marigowda G, Oren E, Israel E, Wechsler ME. Mepolizumab as a steroid-sparing treatment option in patients with Churg-Strauss syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(6):1336–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahn JE, Grandpeix-Guyodo C, Marroun I, Catherinot E, Mellot F, Roufosse F, et al. Sustained response to mepolizumab in refractory Churg-Strauss syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(1):267–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moosig F, Gross WL, Herrmann K, Bremer JP, Hellmich B. Targeting interleukin-5 in refractory and relapsing Churg-Strauss syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(5):341–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.GlaxoSmithKline. Clinical Studies Register 2018. Available from: https://www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/search/?study_ids=115921 Accessed on: February 2, 2018.

- 19.Hellmich B, Flossmann O, Gross WL, Bacon P, Cohen-Tervaert JW, Guillevin L, et al. EULAR recommendations for conducting clinical studies and/or clinical trials in systemic vasculitis: focus on anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(5):605–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Djukanovic R, O'Byrne PM. Targeting Eosinophils in Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(20):1985–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pouliquen IJ, Kornmann O, Barton SV, Price JA, Ortega HG. Characterization of the relationship between dose and blood eosinophil response following subcutaneous administration of mepolizumab. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;53(12):1015–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]