Abstract

The audiovisual speech signal contains multimodal information to phrase boundaries. In three artificial language learning studies with 12 groups of adult participants we investigated whether English monolinguals and bilingual speakers of English and a language with opposite basic word order (i.e., in which objects precede verbs) can use word frequency, phrasal prosody and co-speech (facial) visual information, namely head nods, to parse unknown languages into phrase-like units. We showed that monolinguals and bilinguals used the auditory and visual sources of information to chunk “phrases” from the input. These results suggest that speech segmentation is a bimodal process, though the influence of co-speech facial gestures is rather limited and linked to the presence of auditory prosody. Importantly, a pragmatic factor, namely the language of the context, seems to determine the bilinguals’ segmentation, overriding the auditory and visual cues and revealing a factor that begs further exploration.

Keywords: phrase segmentation, co-speech visual information, artificial grammar learning, bilingualism, prosody, frequency-based information

1 Introduction

Word order varies across the world’s languages, and the basic order of verbs and objects divides them into two major typological classes. A little under half of the world’s languages have a Verb-Object (VO) order, like Spanish or English (e.g., English: I feedVerb the turtleObject), whereas the remaining have an Object-Verb (OV) order instead, like Japanese or Basque (e.g., Basque: dortokaObject elikatzen dutVerb—turtle feed aux-1pers-sg). This typological difference in turn co-varies systematically with a number of other word order phenomena, such as the relative order of functors (e.g., determiners, pronouns, verbal inflection: the, he, walk-ed) and content words (e.g., nouns, verbs, adjectives: turtle, walk, slow). Thus, in VO languages, functors tend to appear phrase-initially (these languages use prepositions, determiners precede nouns, etc., English: of the woman), while in OV languages functors typically occur phrase-finally (they use postpositions, determiners follow nouns, etc., Basque: emakume-a-ren—woman-the-possessive).

Due to their particular properties, functors have been proposed to act as entry points to the structure of natural languages, playing a key role in language processing and language acquisition (Braine, 1963, 1966; Morgan, Meier, & Newport, 1987). Function words signal grammatical relations and are perceptually minimal elements, that is, acoustically less salient than content words. They are typically shorter, unstressed elements, have simpler syllabic structures, etc. (Shi, Morgan, & Allopenna, 1998). Functors tend to occur at the edges of phrases, and—crucially—have a very high frequency of occurrence as compared with content words. Infants and adults can use this frequency information to extract phrases from the input, that is, to parse it into constituents. When presented with structurally ambiguous artificial languages in which frequent and infrequent elements (mimicking functors, and content words, respectively) alternate, both adults and infants parse the unknown languages into phrase-like units that follow the order of functors and content words in the participants’ native languages (Gervain, Nespor, Mazuka, Horie, & Mehler, 2008; Gervain et al., 2013). Phrases provide information about the syntactic structure of sentences. Importantly, the syntactic skeleton of the sentence can be processed independently of lexical semantic information (Gleitman, 1990; Naigles, 1990), as illustrated in Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky poem, where nonsense words replace content words, while function words and hence the syntactic structure are intact: “Twas brillig, and the slithy toves / Did gyre and gimble in the wabe.” Therefore, dividing the input into smaller units might allow us to detect regularities present in them, and potentially help infants bootstrap the acquisition of syntactic phenomena such as basic word order.

Natural languages contain an additional cue1 to phrasal structure and basic word order, namely phrasal prosody. Within phrases, prominence is carried by the content words, and its acoustic realization differs across languages: in VO languages it is realized through increased duration, creating a short-long pattern (English: in Rome), whereas in OV languages it is realized through an increase in pitch or intensity, creating a high-low or loud-soft pattern (Japanese: ^Tokyo ni Tokyo in; Gervain & Werker, 2013; Nespor et al., 2008). Listeners can use phrasal prosody to segment phrases from novel languages (Christophe, Peperkamp, Pallier, Block, & Mehler, 2004; Endress & Hauser, 2010; Gout, Christophe, & Morgan, 2004; Langus, Marchetto, Bion, & Nespor, 2012) and, importantly, prelexical infants use it to parse a structurally ambiguous artificial language into “phrases” having a word order similar to the infants’ native language (Bernard & Gervain, 2012).

A handful of studies have investigated how bilinguals—adults and infants—exploit these two cues to phrases. Adults who are bilingual between Spanish, a VO, functor-initial language, and Basque, an OV, functor-final language, modulate their segmentation preference depending on the language in which they are addressed and receive the instructions of the study (de la Cruz-Pavía, Elordieta, Sebastián-Gallés, & Laka, 2015). This result suggests that they are able to deploy the frequency-based strategies of their two languages. Note however that bilingual listeners of a VO and an OV language are exposed to both functor-initial and functor-final phrases in the speech they hear. The frequency distribution of functors is therefore not sufficient for these listeners to parse the input into syntactic phrases and deduce basic word order. By disambiguating word order, prosodic prominence at the phrasal level has been argued to play a crucial role in bilingual acquisition and processing (Gervain & Werker, 2013). Indeed, 7-month-old bilingual learners of an OV language (e.g., Japanese, Hindi, etc.) and English (VO) parse a structurally ambiguous artificial language that contains changes in duration—a prosodic cue associated with the VO order—into phrase-like chunks that start with a frequent element (mimicking functor-initial phrases), but parse a similar language into frequent-final chunks (mimicking functor-final phrases) when the language contains changes in pitch—a cue associated with OV languages (Gervain & Werker, 2013). However, whether adult listeners can similarly use phrasal prominence to chunk the input remains unknown and is one of the goals of the present research. In sum, the auditory speech signal contains minimally two sources of information to basic word order and phrase segmentation, namely word frequency and phrasal prominence.

Segmenting speech into meaningful units is a crucial step in speech processing: in order to parse the input and access its meaning, we must first locate the boundaries of a hierarchy of morphosyntactically and semantically relevant units, such as morphemes, words and phrases. Word segmentation, which has received the most attention in the literature, results from the integration of several sources of information (Christiansen, Allen, & Seidenberg, 1998; Christiansen, Conway, & Curtin, 2005). Adults primarily rely on lexical information to segment words from their native language(s) (Mattys, White, & Melhorn, 2005). When lexical information is impoverished, they rely instead on segmental, then prosodic and, to a lesser extent, statistical information (Fernandes, Ventura, & Kolinsky, 2007; Finn & Hudson Kam, 2008; Langus et al., 2012; Mattys et al., 2005; Shukla, Nespor, & Mehler, 2007).

Speech perception is inherently multisensory, involving not only the ears but also the eyes. We know that infants and adults readily integrate auditory and visual information while processing language (Burnham & Dodd, 2004; McGurk & MacDonald, 1976; Rosenblum, Schmuckler, & Johnson, 1997), and that these auditory and visual signals consist in turn of the interaction of multiple cues that are only partially informative in isolation (Christiansen et al., 2005; Mattys et al., 2005). However, this research has mainly focused on cue integration at the segment and word levels (e.g., Cunillera, Càmara, Laine, & Rodríguez-Fornells, 2010; Mattys et al., 2005; McGurk & MacDonald, 1976), whereas the role of visual information in processing bigger linguistic units such as phrases and its involvement in syntactic processing remains greatly unexplored and is one of the goals of the present work.

Face-to-face interactions provide three sources of linguistically relevant visual information, namely three types of gesture. In this article, we adopt Wagner, Malisz, and Kopp’s (2014) definition of gesture, as a visible action of any body part produced while speaking. Oral gestures (also known as visual speech) result directly from the production of speech sounds, and are observable mostly but not exclusively in the visible articulators. The literature on phonetic perception has hence focused on the study of these gestures. Co-speech facial gestures refer instead to the head and eyebrow motion that occurs during speech but does not result from the actual production of speech sounds. In turn, other co-speech gestures refer to the spontaneous body movements that accompany speech, such as manual beat gestures. Co-speech gestures are tightly linked to the prosodic structure (Esteve-Gibert & Prieto, 2013; Guellai, Langus, & Nespor, 2014; Prieto, Puglesi, Borràs-Comes, Arroyo, & Blat, 2015), and correlate with phrasal boundaries and phrasal prominence (de la Cruz-Pavía, Gervain, Vatikiotis-Bateson, & Werker, under revision; Esteve-Gibert & Prieto, 2013; Krahmer & Swerts, 2007; Scarborough, Keating, Mattys, Cho, & Alwan, 2009). Importantly, as the prosodic structure in turn aligns with the syntactic structure, these gestures could potentially contribute to syntactic processing. Indeed, manual beat gestures have been shown to impact the interpretation of sentences containing ambiguities at phrase boundaries (Guellai et al., 2014). Here, we seek to determine whether adult listeners use co-speech facial information, specifically head nods, in combination with better-explored cues, namely word frequency and phrasal prosody, to parse speech into syntactic phrases. We have chosen head nods, that is, vertical head movements, as they are the type of head motion (e.g., shakes, nods, tilts) that co-occurs most frequently with speech (Ishi, Ishiguro, & Hagita, 2014), but its role in speech segmentation remains, to date, unexplored.

A handful of studies have shown that adults can use different types of visual information to segment words from speech. They can rely on visual speech, but also non-facial visual information such as looming shapes or static pictures of unrelated objects to segment word-like units from artificial languages, when these are presented in synchrony with or temporally close to “word” boundaries, while disregarding misaligned, asynchronous or non-informative visual information (Cunillera et al., 2010; Mitchel & Weiss, 2014; Sell & Kaschak, 2009; Thiessen, 2010). Indeed, our ability to integrate concurrent auditory and visual information depends on the fact that they are temporally synchronous, though our perceptual system can accommodate a certain degree of desynchronization (Dixon & Spitz, 1980; Lewkowicz, 1996; van Wassenhove, Grant, & Poeppel, 2007). Adults can even segment visual speech alone, in the absence of auditory information (Sell & Kaschak, 2009) or when auditory information is insufficient (Mitchel & Weiss, 2014).

Co-speech facial gestures, such as eyebrow and head movements, correlate with speech acoustics and affect speech perception, despite having great inter- and intra-speaker variability (Dohen, Loevenbruck, & Hill, 2006). Head motion—the gesture that we manipulated in the present work—correlates with changes in F0 and amplitude (Munhall, Jones, Callan, Kuratate, & Vatikiotis-Bateson, 2004; Yehia, Kuratate, & Vaitikiotis-Bateson, 2002), enhances the perception of focus and prominence (Mixdorff, Hönemann, & Fagel, 2013; Prieto et al., 2015), and can even alter their physical realization (Krahmer & Swerts, 2007): head motion is larger in syllables containing lexical or phrasal stress than in unstressed syllables (Scarborough et al., 2009), and the position of prosodic boundaries influences how head nods are timed (Esteve-Gibert, Borràs-Comés, Asor, Swerts, & Prieto, 2017). Head nods have an advantage in signaling prominence and focus over another co-speech facial gesture, eyebrow movements. This advantage of head nods presumably results from their stronger visual saliency, which in turn is likely due to the larger surface occupied by the head as compared with the eyebrows (Granström & House, 2005; Prieto et al., 2015). A recent study (de la Cruz-Pavía et al., under review) has shown that talkers can signal prosodic phrase boundaries by means of head nods combined with eyebrow movements, both across languages (Japanese, English) and speech styles (in infant- and adult-directed speech). Head nods thus provide potential cues to the prosodic structure of utterances. Whether adult listeners can exploit this marker of visual prosody to chunk speech into phrases is yet to be determined and is one of the goals of the current study.

The available literature comparing the processing of audiovisual information by monolingual and bilingual speakers is scarce. Previous research has indicated that bilinguals rely on visual speech to a greater extent than their monolingual peers, presumably as a result of enhanced perceptual attentiveness. Soto-Faraco et al. (2007) showed that adult Catalan-Spanish bilinguals discriminate fluent speech in their two languages solely on the basis of visual speech. Adult monolinguals could successfully discriminate the two languages too, as long as they were familiar with one of them, though with a lower level of accuracy than the bilinguals. In addition, Weikum et al. (2013) found that adult English monolinguals and highly proficient English-other language bilinguals discriminate silent videos of English and French talking faces, but only if they had learned English before age 6 as either their first or second language. This bilingual advantage emerges early in development, as 8-month-old bilingual infants discriminate two familiar or unfamiliar languages based solely on visual speech, unlike monolingual infants of a similar age, and is proposed to be an attentional advantage for bilinguals, particularly to visual information in faces (Sebastián-Gallés, Albareda-Castellot, Weikum, & Werker, 2012). To determine whether a similar advantage obtains in co-speech (facial) visual information, we examine how monolingual and bilingual adults parse the input on the basis of head nods.

In sum, in three studies we explore the contribution of visual, prosodic and frequency-based information to how monolingual and bilingual adults process structure in an artificial language in the absence of lexico-semantic information. We seek to determine whether and how the visual presence of co-speech facial gestures contributes to phrase segmentation, that is, whether this process is bimodal including both auditory and visual information. To that end, we created ambiguous artificial languages in which we systematically manipulated frequency and phrasal prominence—that is, the cues that cross-linguistically impact segmentation—with and without the addition of the co-speech gesture of head nodding, to determine their relative disambiguation of the word order of the unknown languages.

2 Experiment 1

Experiment 1 compares English (VO) monolinguals to bilingual speakers of English and an OV language, on their processing of sets of artificial languages corresponding to a VO word order, but which vary in the number of sources of information they contain (see Figures 1 and 2). We seek to answer two questions. First, can adult monolinguals and bilinguals use the native VO phrasal prosody (i.e., changes in duration) to parse new input into phrase-like units, as observed with prelexical infants (Bernard & Gervain, 2012; Gervain & Werker, 2013)? Secondly, does the inclusion of visual information, specifically head nods, to word frequency and phrasal prosody help them chunk this new input? To do this, we examine participants’ word order preferences for three structurally ambiguous artificial languages in an experiment with three groups of English monolinguals and three groups of English-OV bilinguals.

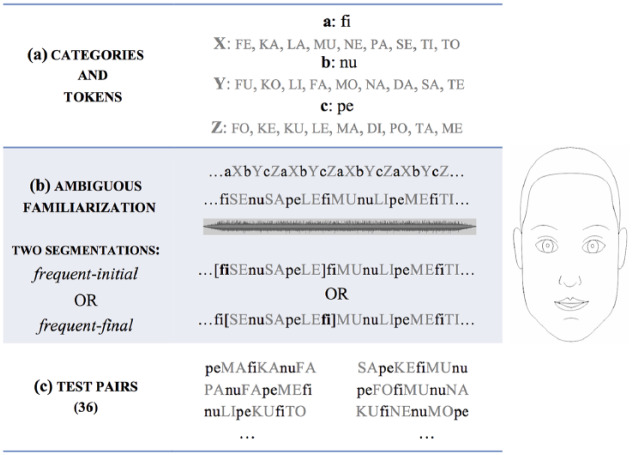

Figure 1.

Shared structure of the artificial languages. The table represents the shared basic structure of the ambiguous artificial languages: (a) the lexical categories and tokens of the languages; (b) the two possible structures of the ambiguous stream; (c) three examples of the 36 test pairs. On the right, a picture of the animated line drawing used in the languages containing visual information.

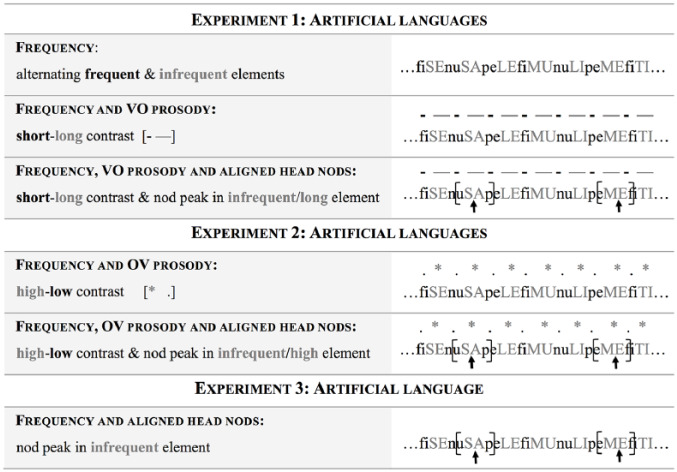

Figure 2.

Graphical depiction of the artificial languages in Experiments 1, 2 and 3. The brackets depict the duration of the head nods, whereas the arrows signal the location of their peak.

A first artificial language contained only frequency-based information. As previous literature has shown that adults can use frequency-based information to parse artificial languages (de la Cruz-Pavía et al., 2015; Gervain et al., 2013), this language is used as a baseline condition with which to probe for additional influence from prosodic and visual information. A frequent-initial segmentation preference is predicted for English monolinguals, as they are speakers of a VO, functor-initial language. For English-OV bilinguals, by contrast, this frequency-only information is ambiguous, so we do not predict a segmentation preference in this population.

A second artificial language combined frequency-based information and a prosodic pattern indicating phrasal prominence in VO languages (henceforth VO prosody), namely, changes in duration. A frequent-initial preference is predicted in English monolinguals, as this prosodic pattern is familiar and congruent with the available frequency-based information. Crucially, this prosodic pattern disambiguates word order for English-OV bilinguals, and hence we predict greater frequent-initial segmentation of this language as compared with the baseline.

A third artificial language contained frequency-based information and VO prosody, as before, and in addition, co-speech facial gestures in the form of head nods aligned with the VO prosody. A frequent-initial segmentation is predicted in mono- and bilinguals exposed to VO prosody and aligned nods. If the presence of head nods facilitates parsing, we predict a greater frequent-initial preference than that obtained when exposed to VO prosody in the absence of visual information.

2.1 Method

2.1.1 Participants

One hundred and forty-four adult participants took part in this experiment. Of these, 72 (50 females, mean age 22.5, age range 17–34) were monolingual speakers of English. Monolingual participants were only included if they reported no exposure to OV languages. All participants were tested in Vancouver (Canada). While there are many different languages spoken in Vancouver, the majority of residents speak English. The considerably smaller number of speakers of other languages prevented us from obtaining a group of sufficiently homogeneous bilingual speakers of English and a single OV language. Thus, the remaining 72 participants (47 females, mean age 21.36, age range 17–34) were highly proficient bilingual speakers of English and any OV language (e.g., Hindi, Korean, Japanese, Farsi, etc.; see Appendix A for a detailed account of their linguistic background). To ensure proficiency in the bilinguals’ OV language, we included only participants who had been raised in homes in which the OV language was spoken. To ensure proficiency in English, we included bilinguals who were taking or had taken university-level courses in this language. In addition, only participants who rated their proficiency both in English and their OV language as 5 or above on a 7-point Likert-scale, both in oral production and comprehension, were retained.2 Participants were either first language OV speakers (n = 53, mean age of acquisition of English: 4.22, range from 0–14), or simultaneous English-OV bilinguals (n = 19). The study was approved by the Behavioural Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia.

2.1.2 Materials

The three ambiguous artificial languages shared the same basic structure, based on Gervain et al. (2013): they all contained two types of lexical categories that differed in the frequency of occurrence of their tokens in the artificial language, mirroring the relative frequency of functors (i.e., frequent elements) and content words (i.e., infrequent elements) in natural languages. Categories a, b, c, were frequent, consisting of a single C(onsonant) V(owel) monosyllabic token. Infrequent categories were X, Y, Z, each of which consisted of nine different monosyllabic CV tokens. The frequent and infrequent categories were combined into a basic hexasyllabic unit with the structure aXbYcZ, which was in turn repeated a predefined number of times (see details below) and concatenated into a familiarization stream of strictly alternating frequent and infrequent elements (see Figure 1). Frequent tokens hence occurred nine times more frequently than infrequent tokens. The structure of the grammar was made ambiguous by suppressing phase information. During synthesis, the amplitude of the initial and final 30 seconds of the stream gradually faded in and out, allowing two possible parses: (a) a frequent-initial segmentation (e.g., aXbYcZ…), characteristic of VO languages, or (b) a frequent-final segmentation (e.g., XbYcZa…), characteristic of OV languages.

The three languages varied in the number of sources of information they contained (see Figure 2): frequency-based information only, frequency-based and prosodic information, and frequency-based, prosodic and visual information. The first artificial language contained only alternating frequent and infrequent elements. All segments were 120 ms long and synthesized with 100 Hz pitch. The six-syllable-long aXbYcZ basic unit was concatenated 377 times into a nine-minute-long stream.

In addition to the alternating frequent and infrequent elements, the infrequent elements of the second artificial language also received prosodic prominence, as in natural languages. The vowel of the infrequent elements was therefore 50 ms longer (i.e., 170 ms, all other segments: 120 ms, all 100 Hz). This value was selected based on measures in natural language and previous publications (Gervain & Werker, 2013). The six-syllable-long aXbYcZ unit was again concatenated 377 times, resulting in a 10-minute-long stream, due to the lengthened segments.

The third artificial language contained frequency-based and VO prosody, as well as co-speech visual information. The visual component consisted of an animated line drawing of a male face (Blender, version 2.75; see Figure 1), producing head nods, that is, vertical head movements. These nods resulted from the combination of two distortions: an increase in head size (as a result of a change in location on the z plane), in addition to a rotation forward of the head with the axis on the drawing’s chin. Each nod had a total duration of 480 ms, divided into a 240 ms stroke phase and a 240 ms retraction phase (i.e., respectively, the period in which the peak of effort in the gesture takes place, and the return into rest position, McNeill, 1992).3 In addition, the avatar’s mouth opened and closed gradually as a function of the stream’s amplitude, in order to increase the perceived naturalness of the avatar without providing detailed segmental information in the form of visual speech. As speakers spontaneously do not produce regularly timed nods, a total of 184 nods—the maximum number possible given our pseudorandomization—were assigned to locations in the stream according to the following principles: there were a minimum of six syllables (i.e., the length of the aXbYcZ basic unit) between consecutive nods, each infrequent category (i.e., categories X, Y, Z) had a roughly equal number of nods, and no more than three consecutive nods fell on the same category. The peak of the head nod occurred at the center of the infrequent and prosodically prominent syllable, providing aligned visual and prosodic information. In order to ensure that participants pay attention to the visual stimuli, we reduced the duration of the familiarization: the six-syllable-long aXbYcZ unit was concatenated 251 times, resulting in a 6 min-39 sec-long stream. Note that adults have been shown to extract regularities based on the computation of frequency-based and visual information after only three minutes of exposure in comparable artificial language learning paradigms (Cunillera et al., 2010; Mersad & Nazzi, 2011).

All languages shared the same test stimuli: 36 auditory-only hexasyllabic items, 18 instantiating a frequent-initial order (e.g., cZaXbY: peMAfiKAnuFA), the remaining 18 a frequent-final order (e.g., YcZaXb: SApeKEfiMUnu; see Figure 1). All test stimuli were prosodically flat, synthesized at 100 Hz, and were 120 ms in duration per segment. All artificial languages and test items were created with the Spanish male voice e1 of MBROLA (Dutoit, 1997), voice also used in Gervain et al. (2013).

2.1.3 Procedure

Participants were tested individually in a quiet room at the Department of Psychology of the University of British Columbia. The stimuli were displayed on a MacBook Pro laptop computer using PsyScope software, and participants were provided with Bose headphones. In the audiovisual condition, the avatar was presented centered on the screen during familiarization. In the auditory-only conditions, no visual information was displayed on the screen. Participants first received brief training in order to become familiarized with the response keys: they listened to 10 pairs of monosyllables (e.g., “so mi”). One of the members of each pair was always the syllable “so.” Participants were asked to identify the target syllable by pressing one of two predefined keys on a keyboard, depending on whether “so” was the first or second member of the pair. The target syllable appeared first in half of the trials, and second in the other half. After training, participants were exposed to the familiarization stream, followed by the test phase consisting of 36 test trials. In each trial, participants heard a frequent-initial and a frequent-final test stimulus separated by a 500 ms pause. The order of presentation was counterbalanced. Each test stimulus appeared twice throughout the experiment, as first and second member of a pair, though not in consecutive trials. In each trial, participants’ task was to choose which member of the pair they thought belonged to the language they had heard during familiarization by pressing one of two predefined keys on the keyboard.

2.2 Results

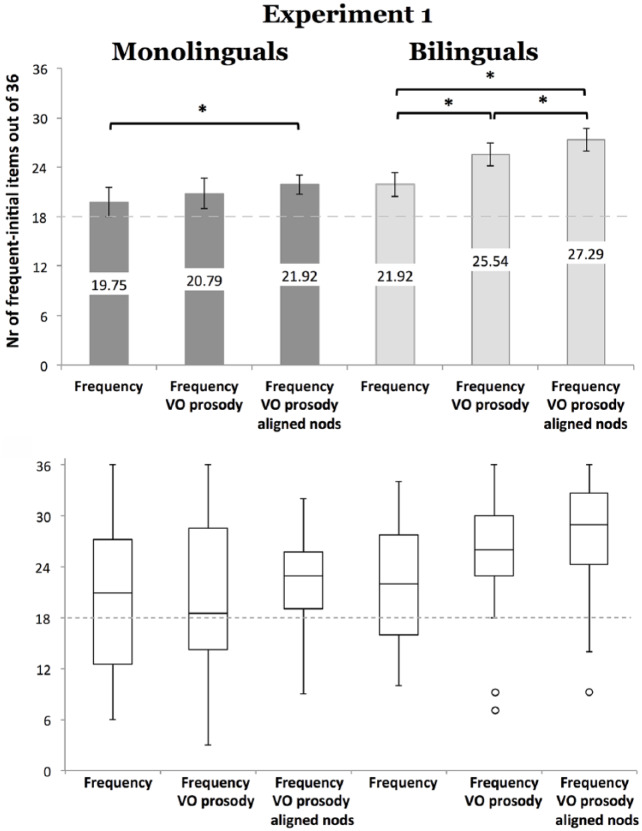

Figure 3 and Table 1 show the number of frequent-initial responses per group out of the 36 trials. Within-group binomial tests of proportions revealed that all groups had a parsing preference that differed significantly from chance (all p ⩽ .005; all analyses were conducted in R, version 3.2.2., R Core Team 2005). All six groups examined segmented the languages into a frequent-initial pattern.

Figure 3.

Word order preferences of the participants in Experiment 1. Bar graphs (top) and boxplots (bottom) with standard error depicting the number and distribution of frequent-initial responses out of the 36 test trials by the monolingual (dark gray columns) and bilingual (light gray columns) participants.

Table 1.

Number (out of the 36 test trials), percentage of frequent-initial responses and confidence intervals (CI) obtained in each of the groups examined in Experiments 1, 2 and 3.

| Number and percentage of frequent-initial responses | ||

|---|---|---|

| Exp.1: Artificial language | Monolinguals | Bilinguals |

| Frequency-based information Frequency and VO prosody Frequency, VO prosody and aligned nods |

19.75/36, 54.86% ±1.77 SE 95% CI [16.08, 23.42] 20.79/36, 57.75%, ±1.82 SE 95% CI [17.03, 24.55] 21.92/36, 60.89%, ±1.21 SE 95% CI [19.41, 24.42] |

21.92/36, 60.89%, ±1.48 SE 95% CI [18.86, 24.98] 25.54/36, 70.94%, ±1.41 SE 95% CI [22.62, 28.46] 27.29/36, 75.81%, ±1.38 SE 95% CI [24.43, 30.15] |

| Exp.2: Artificial language | Monolinguals | Bilinguals |

| Frequency and OV prosody | 16.38/36, 45.50%, ±1.71 SE 95% CI [12.85, 19.90] |

20.92/36, 58.11%, ±1.93 SE 95% CI [16.93, 24,90] |

| Frequency, OV prosody and aligned nods | 16.38/36, 45.50%,±1.74 SE 95% CI [12.77, 19.98] |

21.88/36, 60.78%, ±1.28 SE 95% CI [19.22, 24.53] |

| Exp.3: Artificial language | Monolinguals | Bilinguals |

| Frequency and aligned nods | 20.96/36, 58.22%, ±1.61 SE 95% CI [17.63, 24.28] |

21.83/36, 60.64%, ±1.51 SE 95% CI [18.70, 24.96] |

Binomial tests of proportions are the best-suited test to analyze the participants’ responses, due to their binomial nature (two-alternative forced choice between frequent-initial and frequent-final items). However, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) allows direct comparison with previous literature (Gervain et al., 2013). Therefore, we report the results of both analyses. An ANOVA was conducted with factors Language background (monolingual or bilingual) and Cue type (frequency, or frequency and VO prosody, or frequency, VO prosody and aligned nods), with the number of frequent-initial responses (out of the 36 trials) given by the participants. Significant effects of Language background, F(1, 138) = 10.788, p = .001, partial ŋ2 = .073, and Cue type, F(2, 138) = 3.103, p = .048, partial ŋ2 = .043, were found, but no significant interaction of the two, F(2, 138) = .620, p = .540, partial ŋ2 = .009.

The responses of the three groups of monolinguals were then submitted to a binomial test of proportions, which revealed a significant difference between groups, χ2(2, N = 72) = 6.4, p = .04. All possible pair-wise comparisons of proportions were subsequently carried out with the Holm-Bonferroni method for p-value adjustment.4 Similarly, a binomial test of proportions was conducted with the responses of the three groups of English bilinguals, which revealed a significant difference between these groups, χ2(2, N = 72) = 47, p < .001, followed by all possible pair-wise comparisons of proportions (with Holm-Bonferroni’s correction).

As predicted, a frequent-initial segmentation preference was found in the baseline group of English monolinguals exposed to frequency-based information only. Exposure to the familiar VO prosody did not modulate the segmentation of English monolinguals (p = .41). However, exposure to all cumulative sources of information, namely frequency, VO prosody and aligned nods, led to a significant increase in their frequent-initial segmentation as compared with the baseline group (i.e., the group exposed to frequency only, p = .04), but not to a significant increase compared to the group exposed only to frequency and VO prosody (p = .41).

Frequency-based information is ambiguous for bilinguals, as their input contains both frequent-initial phrases (from English) and frequent-final phrases (from their OV language). The frequent-initial preference observed suggests therefore that they parsed the stream similarly to English and not to their OV language. As predicted, bilingual participants had a greater frequent-initial segmentation when presented with frequency and VO prosody (p < .001). In addition, a greater frequent-initial segmentation was found in the group of bilinguals exposed to frequency, VO prosody and aligned nods, that differed from the one found in the group exposed to only frequency and VO prosody (p = .03), suggesting that the presence of head nods modulated bilinguals’ parsing over and above the effect from prosody.

Finally, in order to directly compare the segmentation of the VO monolingual and VO-OV bilingual participants, the responses of all six groups of participants were submitted to a binomial test of proportions, which revealed a significant difference between groups, χ2(5, N = 144) = 120, p < .001. Separate pair-wise comparisons of proportions were then carried out with the monolinguals and bilinguals’ segmentation preferences of each of the three artificial languages. The results revealed a significant difference between monolinguals and bilinguals in all three artificial languages (frequency: p = .01; VO prosody: p < .001; visual: p < .001), where bilinguals had significantly greater frequent-initial segmentations than their monolingual counterparts.

2.3 Discussion

The present study aimed to examine whether prosodic and co-speech (facial) visual information corresponding to a VO word order facilitated parsing new input into phrase-like units, relative to another source of information that is available in the signal, namely frequency-based cues. To that end, we exposed mono- and bilingual participants to artificial languages that cumulatively combined these three sources of information. The results confirmed that adult speakers can use the combination of frequency-based, prosodic and visual information to chunk new input.

When presented only with frequency-based information, English monolinguals—a previously unexamined population—chose a frequent-initial segmentation of the unknown language, as predicted in VO languages and as observed in English-exposed 7-month-olds (Gervain & Werker, 2013). The adult VO-OV bilinguals also exhibited a frequent-initial preference, despite the fact that frequency-based information is ambiguous to them. We speculate that this preference results from the fact that the study was conducted exclusively in their VO language, English. In previous work it has been shown that bilinguals can modulate their segmentation preferences of artificial languages depending on the language in which they receive the instructions and are addressed during the study: Basque (OV)-Spanish (VO) highly proficient bilinguals produce a greater number of frequent-initial responses when addressed in Spanish, as compared with a similar group addressed in Basque (de la Cruz-Pavía et al., 2015). When faced only with ambiguous frequency-based information, the present bilinguals might have relied on the context to guide their parse.

Interestingly, the bilinguals’ frequent-initial preference was significantly greater than that found in their monolingual counterparts. This result provides supporting evidence to a handful of recent studies showing a bilingual advantage in the detection of statistical regularities (Poepsel & Weiss, 2016; Tsui, Erickson, Thiessen, & Fennel, 2017; Wang & Saffran, 2014). Wang and Saffran (2014) carried out a word-segmentation task using an artificial language with redundant syllable-level and tone-level statistical regularities, and found that bilingual speakers of Mandarin (tonal language) and English (non-tonal) significantly outperformed Mandarin monolinguals (68% vs. 57% respectively). Crucially, the performance of Mandarin monolinguals did not differ from that of English monolinguals (57% vs. 55%), and the performance of the Mandarin-English bilinguals was similar to that of bilingual speakers of two non-tonal languages (68% vs. 66%, e.g., Spanish-English), suggesting that bilingualism enhanced performance. Moreover, bilinguals’ greater implicit learning abilities are observable already from early stages in development and, at 12 months of age, bilingual infants can simultaneously learn two regularities, while monolingual infants only succeed at learning one (Kovács & Mehler, 2009).

Exposure to the familiar VO phrasal prosody (a contrast in duration), which provides information congruent with frequency, did not increase the frequent-initial segmentation preference of English (VO) monolinguals. The lack of a facilitatory effect suggests that this redundant, unambiguous information plays at best a confirmatory role for this population. The adult bilinguals, on the other hand, showed an enhanced frequent-initial preference when exposed to VO prosody. Adult VO-OV bilinguals could parse the available frequency-based information into either of the two orders that characterize their native languages. They might consequently rely to a greater extent on prosodic information as a reliable tool for differentiating their two languages, leading to the observed increase in frequent-initial segmentation. This is consistent with the proposal from Gervain and Werker (2013) that prelexical infants raised bilingual might exploit the combined information provided by phrasal prosody and word frequency to discover the basic word order of verbs and objects of their target languages.

The presence of nods led to a significant increase in the proportion of the bilinguals’ frequent-initial responses, as compared with the group exposed to frequency and prosody in the absence of visual information. This indicates that the addition of co-speech facial gestures facilitated the adult bilinguals’ parsing of the unknown language into phrase-like units, despite the fact that this information was redundant with auditory prosody. The presence of nods also modulated the responses of English monolinguals. When exposed to all three cumulative and redundant cues, monolingual adults significantly increased their frequent-initial segmentation as compared with the frequency-only baseline. Crucially, this enhanced frequent-initial segmentation did not differ from that observed in the monolinguals exposed to frequency and prosody, unlike what was found in their bilingual counterparts.

In sum, these results reveal that speech segmentation involves more than just the auditory modality, as shown by the influence of visual cues in Experiment 1. We acknowledge a limitation of the current design, as we cannot rule out a potential influence of familiarization length in the participants’ performance when presented with prosodic cues versus prosodic and visual cues. Notwithstanding this limitation, our finding that bilingual adults are better able to use this visual information than are monolinguals is consistent with other work showing a bilingual proclivity to utilize visual information in speech. For example, both adults (Soto-Faraco et al., 2007) and prelexical infants (Sebastián-Gallés et al., 2012; Weikum et al., 2007) are better able than monolinguals to discriminate the change from one language to another just by watching silent talking faces. The present study therefore contributes to the literature by revealing a potential bilingual advantage in the use of visual segmentation cues, and specifically non-verbal visual information, that is, in the absence of visual articulatory speech information. Besides allowing adult and infant bilinguals to separate their two languages, visual speech has been shown to help adult participants track relevant information present in two interleaved inputs and segment words from both of them (Mitchel & Weiss, 2010). The present study shows that co-speech facial gestures also help adults chunk the input, and specifically into units bigger than the word, such as phrases. Further, the greater frequent-initial preference observed in the bilinguals’ segmentation of the two auditory-only artificial languages also suggests a potentially greater sensitivity to frequency-based and prosodic cues.

3 Experiment 2

In Experiment 2 we further explore the roles and interplay of prosodic and visual information in adult speech segmentation. Specifically, we examine the processing of English (VO) monolinguals and English-OV bilinguals when presented with artificial languages segmentally identical to the ones used in Experiment 1, but that now contain the prosodic phrasal pattern associated with OV languages. In these languages the element carrying phrasal prominence has higher pitch, as compared with the non-prominent element, resulting in a high-low pattern (Japanese: ^Tokyo ni Tokyo in; Gervain & Werker, 2013; Nespor et al., 2008). This prosodic pattern conflicts with English word order and prosody. To that end, we present two groups of English (VO) monolinguals and two groups of English-OV bilinguals with artificial languages containing: (a) frequency-based information and OV phrasal prosody (i.e., a pitch contrast), and (b) frequency, OV prosody and aligned nods. We did not re-test the frequency-only condition. This condition would be identical to the one conducted in Experiment 1.

The OV prosody is unfamiliar to the English monolinguals. Gervain and Werker (2013) report sensitivity to this non-native prosody in English-exposed 7-month-olds presented with a simplified version of this artificial language, who appear to place equal weight on the conflicting prosodic and frequency-based information. On the other hand, previous studies suggest that adults might weight prosodic information more heavily than statistical information (Langus et al., 2012; Shukla et al., 2007), and that grouping sequences containing changes in pitch (or intensity) into trochaic (high-low or strong-weak) patterns might be a general auditory bias found across languages and even found in rats (Bhatara, Boll-Avetisyan, Unger, Nazzi, & Höhle, 2013; Bion, Benavides-Varela, & Nespor, 2011; Langus et al., 2016; de la Mora, Nespor, & Toro, 2013). In the artificial language containing frequency-based information and OV phrasal prosody, infrequent elements received higher pitch than frequent elements. A trochaic grouping of this language hence results in a frequent-final segmentation, which in turn conflicts with the frequent-initial segmentation signaled to these English (VO) speakers by the word frequency cues. No clear prediction can therefore be drawn, given the potentially conflicting information provided by the unfamiliar prosodic information and the familiar frequency-based information in the current experiment. A frequent-initial segmentation would suggest that frequency-based information outweighs the proposed universal prosodic grouping bias, whereas a frequent-final segmentation would indicate a stronger prosodic grouping bias that overrides the familiar frequency information. Similarly, we make no clear prediction for the segmentation preference of English monolinguals exposed to the unfamiliar OV prosody and aligned visual information. Monolinguals might interpret this source of information as an independent cue converging with the familiar frequency-based information or, alternatively, as a visual marker of phrasal prosody.

A frequent-final preference is expected to obtain in English-OV bilinguals, as the OV prosodic pattern is familiar to them and disambiguates word order, and prosody had a facilitatory effect in Experiment 1. Similarly, we predict that bilinguals will display a frequent-final segmentation of the language containing OV prosody and aligned nods and, given the facilitatory effect of visual cues obtained in Experiment 1, greater than the one observed when exposed to OV prosody in the absence of visual information.

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants

Ninety-six adult participants took part in this experiment. Of these, 48 (35 females, mean age 20.83, age range 17–29) were monolingual speakers of English. The remaining 48 participants (36 females, mean age 21.46, age range 18–35) were highly proficient bilingual speakers of English and any OV language (see Appendix A). Inclusion criteria were identical to those presented in Experiment 1. The study was approved by the Behavioural Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia.

3.1.2 Materials

We designed two further ambiguous artificial languages with the same basic structure and the same auditory-only, prosodically flat test items as in Experiment 1, synthesized with the same Spanish male voice of MBROLA (see Figure 1). The two languages varied in the number of sources of information they contained (see Figure 2). A first language contained frequency-based information and the prosodic pattern associated with OV languages (i.e., a pitch contrast). The vowel of the infrequent elements was hence 20 Hz higher in pitch (i.e., 120 Hz, all other segments: 100 Hz, all 120 ms). The six-syllable-long aXbYcZ unit was again concatenated 377 times, resulting in a nine-minute-long stream. The second language contained frequency-based information and OV prosody, as well as co-speech visual information, namely the same avatar as in Experiment 1 producing head nods. The visual component was identical to the one described in Experiment 1. The peak of the head nod was aligned with the center of the infrequent and prosodically prominent syllable. The duration of the familiarization was again reduced to six minutes, in order to ensure that participants pay attention to the visual stimuli.

3.1.3 Procedure

The procedure was identical to that of Experiment 1.

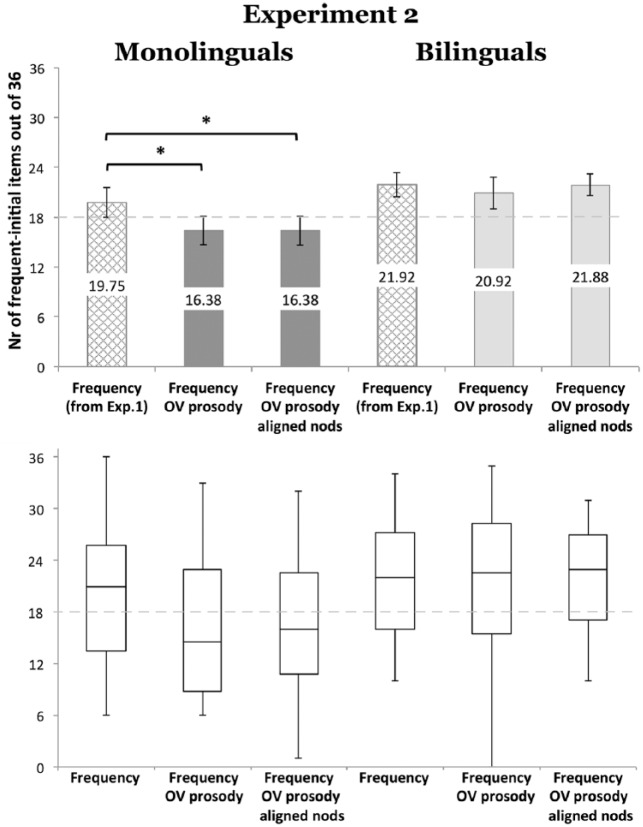

3.2 Results

Figure 4 and Table 1 show the number of frequent-initial responses per group out of the 36 trials. Within-group binomial tests of proportions revealed that all groups had a parsing preference that differed significantly from chance (all p ⩽ .009; all analyses were conducted in R). The two groups of monolinguals had a frequent-final segmentation preference, whereas the two groups of bilinguals segmented the languages into a frequent-initial pattern.

Figure 4.

Word order preferences of the participants in Experiment 2. Bar graphs (top) and boxplots (bottom) with standard error depicting the number and distribution of frequent-initial responses out of the 36 test trials by the monolingual (dark gray columns) and bilingual (light gray columns) participants. Note that the patterned columns in the top figure depict Exp.1’s groups exposed to frequency-only information, that is, the baseline groups. Experiment 1 and 2’s artificial languages share the same tokens and test items.

The responses of the four groups were submitted to an ANOVA, together with the results of Experiment 1’s frequency-only baseline groups (Cue type: frequency, or frequency and OV prosody, or frequency, OV prosody and aligned nods). An effect of Language background obtained, F(1, 138) = 8.958, p = .003, partial ŋ2 = .061, but no effect of Cue type, F(2, 138) = .954, p = .388, partial ŋ2 = .014, or interaction, F(2, 138) = .531, p = .589, partial ŋ2 = .008.

We then compared the responses of the two groups of monolinguals exposed to OV prosody (with or without aligned nods) to Experiment 1’s frequency-only baseline group. These three groups were submitted to a binomial test of proportions, which revealed a significant difference between groups, χ2(2, N = 72) = 20, p < .001. The three possible pair-wise comparisons of proportions were subsequently carried out (with Holm-Bonferroni correction). Both groups exposed to the unfamiliar OV prosody parsed the languages into a frequent-final pattern, and the preferences of these two groups exposed to OV prosody and to OV prosody and aligned nods differed significantly from the preference observed in Experiment 1’s frequency-only baseline group (both p < .001). The presence of head nods did, however, not modulate their segmentation, as the preference of the group exposed to OV prosody did not differ statistically from that of the group exposed to OV prosody and aligned nods (p = 1.0).

A binomial test of proportions was conducted comparing the responses in three groups: the two groups English-OV bilinguals exposed to OV prosody with or without aligned nods and the baseline group from Experiment 1. No significant difference obtained between these three groups, χ2(2, N = 72) = 1.8, p = .4. Therefore, no further pair-wise comparisons of proportions were conducted.

As in Experiment 1, we directly compared the segmentation preferences of the monolingual and bilingual participants. We submitted the responses of all six groups of participants to a binomial test of proportions that revealed a significant difference between groups, χ2(5, N = 144) = 89, p < .001. Separate pair-wise comparisons of proportions were then carried out with the monolinguals and bilinguals’ segmentation preferences of each of the two artificial languages. The results revealed a significant difference between monolinguals and bilinguals in both languages (both OV prosody and visual: p < .001), where bilinguals segmented both languages in a frequent-initial pattern, whereas monolinguals showed the opposite segmentation.

3.3 Discussion

Experiment 2 further explored the interplay of prosodic and visual information relative to frequency-based information in adult speech segmentation. Specifically, we examined whether adult English monolinguals and English-OV bilinguals could use the prosodic pattern associated with OV languages, namely a pitch contrast, to segment new input. Though this prosodic pattern is not familiar to the English (VO) monolinguals, it has been proposed that a general auditory bias leads to a trochaic (high-low or strong-weak) grouping of this pattern. In addition, we further explored the relative contribution of co-speech facial gestures, namely head nods, in locating phrase-like units. Two groups of English monolinguals and two groups of English-OV bilinguals were hence presented with artificial languages containing (a) frequency and OV prosody (i.e., a pitch contrast), and (b) frequency, OV prosody and aligned nods.

Though OV prosody is unfamiliar for the two groups of English monolinguals, a trochaic grouping of the artificial language such as proposed in the literature (Bion et al., 2011) would result in a frequent-final segmentation, while the frequency-based information signals the opposite frequent-initial parse. Both groups of monolinguals (with or without aligned visual information) showed the frequent-final segmentation associated with the unfamiliar prosody, and which differed from the frequent-initial parse found in the frequency-only baseline. When in conflict, adult monolinguals hence placed a greater weight on prosodic than frequency-based information, even if unfamiliar. These results are in consonance with previous literature on adult word segmentation (Langus et al., 2012; Shukla et al., 2007), and provide supporting evidence of the proposed perceptual bias (Bion et al., 2011; de la Mora et al., 2013; Langus et al., 2016). Interestingly, these results differ from those observed with 7-month-old infants, who are sensitive to prosody but seem to weigh it equally to frequency-based information (Gervain & Werker, 2013).

Surprisingly, neither of the two OV prosody-exposed bilingual groups showed the predicted frequent-final segmentation—unlike their monolingual counterparts—but a frequent-initial preference similar to the one found in the baseline group. Sensitivity to this pitch contrast has been attested in prelexical bilingual infants: 7-month-old English-OV bilinguals segment a simplified version of the present artificial language containing OV prosody in a frequent-final pattern (Gervain & Werker, 2013). The strong frequent-initial segmentation obtained in the frequency-only baseline suggests that bilingual participants might have relied on the language of the context to parse the artificial language. Further, frequency-based cues are ambiguous to OV-VO bilinguals and therefore not in conflict with prosody. We argue that bilinguals instead perceived OV prosody and language of the context as being in conflict, and that the language of the context outweighed prosody, leading bilinguals to inhibit the other language perceived as non-target. A condition in which bilinguals are set in an OV language context is required to confirm this interpretation. Unfortunately, such a condition is at present unfeasible due to the high number of OV languages spoken by the bilingual participants.

The addition of aligned nods had no facilitatory effect in the segmentation of English monolinguals. The visual cue provided ambiguous information to this population. The nods could be interpreted as visual correlates of the unfamiliar OV prosody, or they could simply have been perceived as a marker of prominence, independent from the specific auditory prosody available. There are minimally three potential interpretations of the lack of a facilitatory effect. On the one hand, the English monolinguals might have ignored the uninformative visual cues and relied solely on the auditory information. Previous studies have shown that adults disregard visual information perceived as unreliable and instead focus on the more stable auditory sources of information available (Cunillera et al., 2010; Mitchel & Weiss, 2014). Alternatively, they might have treated the co-speech facial gestures simply as confirmatory of the order signaled by either the frequency (frequent-initial) or prosodic information (frequent-final). This interpretation is less likely, given the facilitatory effect of visual cues obtained in Experiment 1 as compared with the frequency-only baseline. Finally, the strong auditory bias might have washed out any weak effect of visual cues such as those obtained in the monolinguals exposed to the familiar VO prosody in addition to aligned nods. The fact that this bias overrode the segmentation preference for the familiar frequency-based information found in the baseline could be interpreted as supporting evidence.

The presence of OV prosody and aligned nods provides cumulative, congruent information to the adult bilinguals and yet, the addition of visual cues did not modulate their segmentation preference. This result contrasts with the facilitatory effect found when presented with visual cues aligned with VO prosody. We argue that it again results from the strong effect of context, which overrides the information provided by the prosodic and visual cues, and leads to a frequent-initial parse of the artificial language. Note that the nods, aligned with the infrequent and prosodically prominent syllables, could potentially have been interpreted as an independent cue concurrent with frequency (and interpreted as frequent-initial), or as a visual correlate of the OV prosody. It is therefore possible that they were deemed uninformative and consequently disregarded.

4 Experiment 3

Experiments 1 and 2 compared the role and interplay of auditory prosody and co-speech facial gestures in speech segmentation by adult English monolinguals and English-other OV language bilinguals on sets of artificial languages corresponding to VO and OV word orders. In these experiments, the presence of visual cues—that is, head nods—facilitated the segmentation of an artificial language containing VO prosody, but not OV prosody, though bilingual listeners benefited more from the presence of visual information than monolingual listeners. The origin of this asymmetry is unclear. In Experiment 3, we further explore the role of visual information, in order to determine whether adult listeners can use this information in the absence of auditory prosody or whether, alternatively, these visual cues only facilitate segmentation if concurrent with auditory prosody. To that end, we presented a group of English (VO) monolinguals and a group of English-OV bilinguals with an artificial language containing frequency-based information and aligned nods, in the absence of auditory prosodic information. We used the frequency-only condition in Experiment 1 as the baseline of comparison.

If the presence of head nods facilitates segmentation in the absence of convergent auditory prosody information, we predict a greater frequent-initial segmentation preference than the one obtained in the frequency-only baseline. If, however, head nods only reinforce auditory prosody and is not an independent segmentation cue, we predict no difference with respect to the frequency-only baseline.

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Participants

Forty-eight adult participants took part in this experiment. Of these, 24 (19 females, mean age 21.38, age range 18–34) were monolingual speakers of English, and the remaining 24 participants (15 females, mean age 20.67, age range 18–30) were highly proficient bilingual speakers of English and any OV language (see Appendix A). Inclusion criteria were identical to those presented in Experiments 1 and 2. The study was approved by the Behavioural Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia.

4.1.2 Materials

We designed an ambiguous artificial language with the same segmental inventory (i.e., tokens), basic structure and the same auditory-only, prosodically flat test items as in Experiments 1 and 2 and synthesized with the same Spanish male voice of MBROLA (see Figures 1 and 2). This language contained frequency-based information—alternating frequent and infrequent elements—accompanied with co-speech facial gestures (i.e., head nods), but no prosodic information (all segments: 100 Hz, 120 ms). The basic hexasyllabic aXbYcZ unit was concatenated 251 times, resulting in a six-minute-long stream, as in all previous audiovisual conditions. The visual component was identical to Experiments 1 and 2, and the peak of the head nod was aligned with the center of the infrequent syllable.

4.1.3 Procedure

The procedure was identical to that of Experiments 1 and 2.

4.2 Results

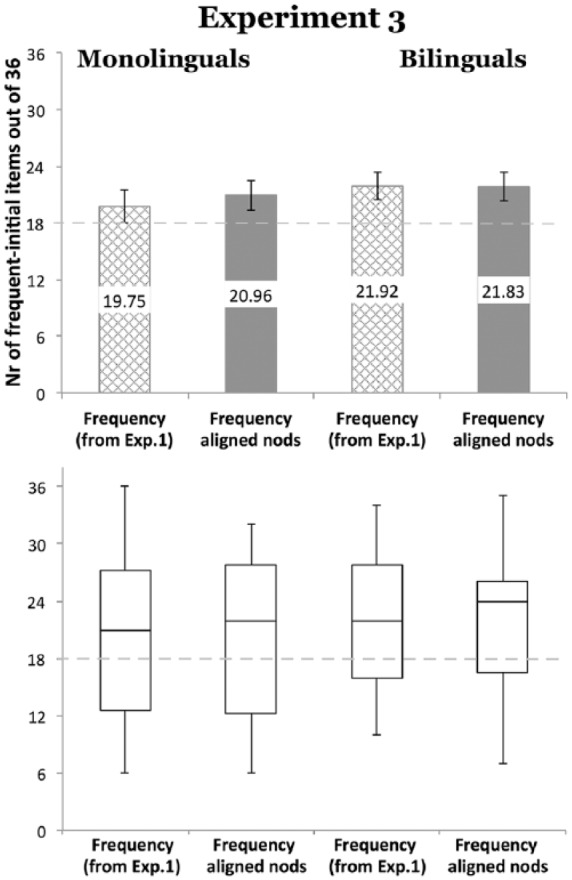

Figure 5 and Table 1 show the number of frequent-initial responses per group out of the 36 trials. Within-group binomial tests of proportions revealed that both groups had a frequent-initial preference that differed significantly from chance (both p ⩽ .001).

Figure 5.

Word order preferences of the participants in Experiment 3. Bar graphs (top) and boxplots (bottom) with standard error depicting the number and distribution of frequent-initial responses out of the 36 test trials by the monolingual (dark gray columns) and bilingual (light gray columns) participants. The patterned columns in the top figure depict Exp.1’s groups exposed to frequency-only information, that is, the baseline groups. Experiment 1, 2 and 3’s artificial languages share the same tokens and test items.

We compared the responses of the two groups exposed to frequency and aligned nods to Experiment 1’s two frequency-only baseline groups. An ANOVA (Cue type: frequency or frequency and aligned nods) revealed no effect of Language background, F(1, 92) = .907, p = .343, partial ŋ2 = .010, Cue type, F(1, 92) = .124, p = .726, partial ŋ2 = .001, or interaction, F(1, 92) = .164, p = .687, partial ŋ2 = .002.

We then compared the responses of the group of monolinguals exposed to frequency and aligned nods, to Experiment 1’s frequency-only baseline group. A binomial test of proportions revealed no significant difference between the two groups, χ2(1, N = 48) = 1.8, p = .2. Likewise, a binomial test of proportions conducted with the responses of the English-OV bilinguals and Experiment 1’s baseline group revealed no significant difference between these two groups, χ2(1, N = 48) = 0.002, p = 1.0. The addition of head nods to the frequency-based cues did therefore not modulate the segmentation of bilinguals or monolinguals. As in the previous experiments, we directly compared the segmentation preferences of the monolingual and bilingual participants. A binomial test of proportions revealed no difference between them, χ2(1, N = 48) = .96, p = .3.

4.3 Discussion

Experiment 3 examined whether adult English monolinguals and English-OV bilinguals could use co-speech facial gesture information to segment new input in the absence of auditory prosody. We presented monolinguals and bilinguals with an artificial language containing frequency-based and visual cues but flat—that is, no distinguishing—auditory prosody, and compared their segmentation preferences to the ones obtained in Experiment 1’s frequency-only baseline.

As in Experiments 1 and 2, the peak of the nods was aligned with the center of infrequent elements, that is, the elements receiving phrasal prominence in natural languages. Interestingly, the presence of this visual cue did not facilitate segmentation in either population. This result suggests that head nods are not interpreted as markers of prosodic prominence independent of auditory prosody. Rather, the co-speech facial gesture of head nodding appears to be a visual correlate of this particular aspect of auditory prosody.

5 General discussion

In three artificial language learning studies we investigated whether adult monolinguals and bilinguals can use phrasal prosody and head nods to chunk new input. Experiment 1 explored their processing of artificial languages that contained cues associated with a V(erb)-O(bject) order, Experiment 2 examined their processing of languages that corresponded to an OV order, and Experiment 3 investigated the roles of auditory prosody and visual information in segmentation. We explored the interplay of these two cues relative to frequency-based information, which is a segmentation cue available to both of these two populations (de la Cruz-Pavía et al., 2015; Gervain et al., 2008). The results of Experiments 1, 2 and 3 revealed that frequency, prosody and visual information modulated the segmentation preferences of monolinguals and bilinguals, though they exhibited interesting differences.

Both populations used frequency-based information to parse the artificial languages. This use of frequency cues is in accordance with prior literature, and extends it to a language previously untested with adults, namely English. Importantly, this is the first VO language in which a clear frequent-initial segmentation preference is reported in adulthood. Gervain et al. (2013) examined monolingual speakers of Italian and French (both VO) with a similar artificial language and found that their preferences did not differ from chance—though were numerically frequent-initial—whereas speakers of Japanese and Basque (both OV languages) had a clear frequent-final preference. Gervain et al. (2008) argued that this asymmetry mirrors the distributional properties of these languages: Japanese and Basque are strongly functor-final, while French and Italian are functor-initial languages that allow extensive suffixation. Crucially, English has much more limited suffixation and is hence the language with the most predominantly functor-initial statistical distribution tested to date in this paradigm. The frequent-initial segmentation obtained in the current study thus confirms the suggestion that adults closely match the input statistics of their native language(s) (Gervain et al., 2013). Interestingly, this statistical cue facilitated segmentation significantly more in bilinguals than monolinguals. This bilingual advantage aligns with those reported in other recent studies on the detection of statistical regularities (Poepsel & Weiss, 2016; Tsui et al., 2017; Wang & Saffran, 2014).

The presence of phrasal prosody modulated differently the segmentation preferences of adult monolinguals and bilinguals. The presence of a contrast in duration led to a frequent-initial segmentation in bilinguals while a contrast in pitch led to a frequent-final segmentation preference in monolinguals. Redundant information such as the familiar VO prosody (a contrast in duration) only appears to play a confirmatory role in English monolinguals, and does not modulate segmentation. However, these monolinguals show a strong auditory bias towards chunking sequences containing changes in pitch (i.e., OV prosody) into trochees (a high-low pattern), despite this being an unfamiliar prosody, and which even outweighs the familiar frequency-based information. By contrast, only the phrasal prosody characteristic of the language of the context (i.e., English) facilitated segmentation of English-OV bilinguals.

The frequent-initial order obtained in the group of bilinguals presented only with frequency information—ambiguous to these VO-OV speakers—and the surprising lack of an effect of prosody in the two groups of OV-exposed bilinguals (with or without aligned nods), suggests that the language of context (that is, the language in which they are addressed and receive the instructions of the study) might have determined their segmentation. Further, the language of context appears to be more heavily weighed than the available auditory (and visual) cues. Note that all participants, monolinguals and bilinguals, were exclusively addressed in English, their VO, frequent-initial language, during the study. A context language effect has been previously reported in Basque-Spanish bilinguals (de la Cruz-Pavía et al., 2015). Importantly, the effect of context does not turn bilinguals into monolinguals. One possible explanation is that, unlike English monolinguals, English-OV language bilinguals need to actively ignore their OV language when in an English context, which might have led to a particularly heightened insensitivity to the OV prosody observed in bilinguals. By contrast, monolinguals do not have to actively ignore another linguistic structure, and hence might have been more sensitive to the unfamiliar prosody.

The addition of visual information also modulated the segmentation preferences of adult monolinguals and bilinguals, though its impact was quite limited. Notably, the presence of head nods facilitated segmentation only in the presence of concurrent auditory prosody and, specifically, only when aligned with VO prosody, that is, the prosody characteristic of the bilinguals’ context language (English), or the English monolinguals’ native prosody. These results suggest that head nods are not an independent cue to segmentation, but rather a cue to the prosodic structure of the input, which in turn assists in segmentation. Previous literature has reported a tight coupling between this co-speech facial gesture and auditory prosody: the presence of head nods enhances perception of auditory prosodic prominence and even alters its realization (Krahmer & Swerts, 2007; Mixdorff et al., 2013; Prieto et al., 2015). Despite methodological differences in study design and stimulus properties, the present results provide further support for the hypothesis that prosody is not exclusively auditory but multimodal, and suggest that the role of visual markers of prominence—at least in the form of head nods—might be limited to reinforcing the listener’s auditorily perceived prominence.

Interestingly, the influence of visual information appeared to be weaker in the monolingual population. Hence, as found in visual speech in other areas of speech processing such as language discrimination (Soto-Faraco et al., 2007; Weikum et al., 2013), bilinguals seem to rely on co-speech facial gestures to a greater extent than their monolingual peers. The weak influence of co-speech facial gestures in monolinguals might result from the fact that the auditory stimuli were presented in optimal acoustic conditions. Previous research has shown that adults and even infants benefit most from other types of visual information such as visual speech in noisy environments or when the available auditory information is unreliable. Specifically, seeing talking faces increases speech intelligibility most in low acoustic signal-to-noise ratios (Grant & Seitz, 2000; Sumby & Pollack, 1954), and most clearly enhances segmentation of a stream when there is minimal statistical information (Mitchel & Weiss, 2014), or when auditory streams compete (Hollich, Newman, & Jusczyk, 2005). Though there is clear evidence that adult listeners can chunk word-like units from the input when presented with (facial or non-facial) visual-only cues, evidence of a facilitatory effect of visual information in segmentation accuracy is less clear when the visual cues accompany clear speech and/or robust auditory cues. For example, Mitchel and Weiss (2010) and Sell and Kaschak (2009) found no difference in the segmentation accuracy of auditory-only and audio-visual stimuli consisting of talking faces, whereas Cunillera et al. (2010) and Thiessen (2010) reported a facilitatory effect of visual information consisting of images of objects or looming shapes.5 Given the facilitatory effect obtained with adult bilinguals and the significant increase of the responses of monolingual participants exposed to frequency, VO prosody and aligned head nods as compared with frequency only, we speculate that the use of co-speech facial gestures in the present artificial languages might be enhanced if accompanied by speech presented in suboptimal auditory conditions.

In sum, frequency-based, phrasal prosody and co-speech visual information seem to play a role in the segmentation strategies of intact speech by adult bilinguals and monolinguals, though their interplay differs in these two populations. As found in word segmentation (Mattys et al., 2005), these cues to phrase segmentation appear to be hierarchically organized, so that some cues are more heavily weighed than others. Moreover, when pitted against each other, monolinguals weigh prosodic cues more heavily than statistical cues, as also reported in word segmentation (Langus et al., 2012; Shukla et al., 2007). This result suggests that a similar hierarchy of segmentation cues might drive the segmentation of linguistic units at the word and phrase levels. However, in order to confirm this hypothesis, further research is planned that will examine the interplay of statistical and prosodic cues with other word-segmentation cues (e.g., acoustic-phonetic cues, lexico-semantic information). Importantly, the language of context seems to drive the segmentation preferences of adult bilinguals, as found by de la Cruz-Pavía et al. (2015) with Basque-Spanish bilinguals, revealing the need for further exploration of this factor. Finally, we plan to investigate the role of co-speech visual information in phrase segmentation, using more ecological stimuli than the present studies’ line drawing animation.

6 Conclusions

In a study with 12 groups of English monolinguals and English-OV bilinguals, we show that adult listeners can use co-speech facial gestures, specifically head nods, to parse an artificial language into phrase-like units, though their use appears to be limited and linked to the presence of auditory prosody. In addition, adult bilinguals and monolinguals can rely on two sources of information to phrase boundaries, namely word frequency and phrasal prosody. Monolinguals presented with conflicting cues seem to weigh prosody more heavily, whereas the bilinguals’ segmentation appears to be determined by the language of the context. These results provide evidence that adult listeners are able to extract multimodal sources of information present in the signal to chunk the input into phrases. Further, these results suggest that adults integrate these cues in a hierarchical fashion, as has been proposed in word segmentation (Mattys et al., 2005). Structuring the input into phrases is pivotal to the acquisition and processing of the grammar (Morgan et al., 1987).

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to our friend and colleague Eric Vatikiotis-Bateson. You are sorely missed. We wish to thank Jéssica Zabala for designing the line drawing, and Stanislaw Nowak for his crucial help animating it. We are indebted to Nathalie Czeke, Prudence Dong, Tisha Sandhu and Sarah Smith for their great help recruiting and testing the participants.

Appendix A: Participants’ linguistic background information

Table 2.

Age, gender and linguistic background information of the six groups of English-OV bilinguals examined.

| ENGLISH – OV BILINGUAL PARTICIPANTS | Frequency | Frequency & VO prosody | Frequency, VO prosody & aligned nods | Frequency & OV prosody | Frequency, OV prosody & aligned nods | Frequency & aligned nods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age & range | 21.79 (18-34) |

21.00 (17-30) |

21.29 (17-29) |

20.88 (18-25) |

22.04 (18-35) |

20.67 (18-30) |

| Sex | 17F-7M | 16F-8M | 14F-10M | 18F-6M | 18F-6M | 15F-9M |

| Nr of English-dominant participants (self-reported) | 14 | 17 | 10 | 14 | 15 | 11 |

| AoA of English & range | 4.42 (0-14) |

3.98 (0-10) |

4.25 (0-8) |

4.67 (0-11) |

5.42 (0-12) |

5.83 (0-15) |

|

Nr of simultaneous

English-OV bilinguals |

7 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Nr of sequential bilinguals (all with OV as L1) | 17 | 16 | 20 | 21 | 21 | 20 |

| English: understanding | 6.71 | 6.71 | 6.67 | 6.79 | 6.79 | 6.67 |

| OV language: understanding | 6.54 | 6.42 | 6.63 | 6.38 | 6.54 | 6.75 |

| English: speaking | 6.67 | 6.63 | 6.46 | 6.79 | 6.58 | 6.63 |

| OV language: speaking | 6.38 | 6.04 | 6.54 | 6.13 | 6.38 | 6.58 |

Table 3.

List of OV languages spoken by the English-OV participants, and distribution in each of the six groups examined.

| OV LANGUAGES PER GROUP |

Frequency | Frequency & VO prosody |

Frequency, VO prosody & aligned nods |

Frequency & OV prosody |

Frequency, OV prosody & aligned nods |

Frequency & aligned nods | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bengali | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Burmese | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Farsi | 6 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 23 |

| Gujarati | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hindi | 3 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 17 |

| Japanese | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 17 |

| Korean | 5 | 7 | 8 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 46 |

| Marathi | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Odia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Punjabi | 4 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 27 |

| Tamil | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Urdu | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

Table 4.

Age and gender of the six groups of English monolinguals examined.

| ENGLISH MONOLINGUAL PARTICIPANTS | Frequency | Frequency & VO prosody | Frequency, VO prosody & aligned nods | Frequency & OV prosody | Frequency, OV prosody & aligned nods | Frequency & aligned nods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age & range | 23.54 (17-32) |

22.92 (18-34) |

21.04 (18-29) |

21.13 (18-29) |

20.54 (17-28) |

21.38(18-34) |

| Sex | 18F-6M | 16F-8M | 16F-8M | 18F-6M | 17F-7M | 19F-5M |

In this article, the term cue will refer to the information available in the signal, and be used interchangeably with the term source of information. It is the goal of this study to determine whether a subset of these cues is indeed used by the listener to parse speech.

The participants’ linguistic background was collected by means of a detailed questionnaire, modified from that developed by members of the research group The Bilingual Mind, of the University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU. The questionnaire measured exposure to and use of the two languages in everyday life at three points of development: infancy, adolescence, and adulthood.

Mixdorff et al. (2013) report a duration of 600 ms of a light naturally produced nod. The shortened duration of the present nods results from the special nature of the languages’ 240–290 ms long monosyllabic elements.

Holm-Bonferroni Method is a sequentially rejective multiple test procedure, more powerful than the classic and single-step Bonferroni method but that also controls well for Type 1 errors. In this method, uncorrected p-values of all hypotheses are first calculated and ranked. The hypothesis (H) with the lowest uncorrected p-value then receives Bonferroni correction involving the total number of comparisons (k; i.e., α/k). The second lowest p-value is then corrected using the Bonferroni method with all hypotheses − 1 (i.e., α/k-1); and so on for the remaining hypotheses. Applied to Experiment 1, where α = .05 and k = 3: Hlowest p-value: p corrected to .05/3, Hsecond lowest p-value: p corrected to .05/2, and Hthird lowest p-value: p corrected to .05/1. Calculation of the uncorrected p-values and application of the Holm-Bonferroni method is automatically carried out by R which returns the corrected p-values. We report these corrected p-values in the manuscript.

Though both find above-chance accuracy in auditory-only baselines and when visual information is misaligned.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by a Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship within the EU Seventh Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development (2007–2013) under REA grant agreement no. [624972] awarded to I. de la Cruz-Pavía, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (RGPIN-2015-03967 and Discovery Grant 81103) and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (435-2014-0917) grants to J. F. Werker, as well as the French Investissements d’Avenir – Labex EFL program (ANR-10-LABX-0083), ANR grant (ANR-15-CE37-0009-01), and ERC Consolidator Grant (773202 ERC-2017-COG ‘BabyRhythm’) to J. Gervain.

ORCID iD: Irene de la Cruz-Pavía  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3425-0596

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3425-0596

Contributor Information

Irene de la Cruz-Pavía, Integrative Neuroscience and Cognition Center (INCC—UMR 8002), Université Paris Descartes (Sorbonne Paris Cité), France; Integrative Neuroscience and Cognition Center (INCC—UMR 8002), CNRS, France.

Janet F. Werker, Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, Canada

Eric Vatikiotis-Bateson, Department of Linguistics, University of British Columbia, Canada.

Judit Gervain, Integrative Neuroscience and Cognition Center (INCC—UMR 8002), Université Paris Descartes (Sorbonne Paris Cité), France; Integrative Neuroscience and Cognition Center (INCC—UMR 8002), CNRS, France.

References

- Bernard C., Gervain J. (2012). Prosodic cues to word order: What level of representation? Frontiers in Psychology, 3. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatara A., Boll-Avetisyan N., Unger A., Nazzi T., Höhle B. (2013). Native language affects rhythmic grouping of speech. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 134, 3828–3843. doi: 10.1121/1.4823848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bion R. A. H., Benavides-Varela S., Nespor M. (2011). Acoustic markers of prominence influence infants’ and adults’ segmentation of speech sequences. Language and Speech, 54, 123–140. doi: 10.1177/0023830910388018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braine M. D. (1963). On learning the grammatical order of words. Psychological Review, 70, 323–348. doi: 10.1037/h0047696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braine M. D. (1966). Learning the positions of words relative to a marker element. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 72, 532–540. doi: 10.1037/h0023763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]