Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has added an additional layer of complexity to endovascular treatment (EVT) for acute ischaemic stroke. Drawing on recently published guidelines, this article provides a conceptual framework for EVT in the COVID-19 era, outlining key principles for ensuring safe and timely EVT while minimizing the risk of infectious exposure for health-care workers and patients.

Subject terms: Stroke, Infectious diseases

Refers to Smith, M. S. et al. Endovascular therapy for patients with acute ischemic stroke during the COVID-19 pandemic: a proposed algorithm. Stroke 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.029863 (2020). | Nguyen, T. N. et al. Mechanical thrombectomy in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic: emergency preparedness for neuroscience teams: a guidance statement from the Society of Vascular and Interventional Neurology. Stroke 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030100 (2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic presents substantial challenges for acute stroke treatment. Not only do patients with COVID-19 seem to be more vulnerable to cerebral ischaemia1, but the need to screen patients with acute stroke for COVID-19 symptoms and impose additional protective measures to promote infectious control in the ambulance and neuroangiography suite and on hospital wards carries the risk of substantial treatment delays. Endovascular treatment (EVT) for stroke is a powerful approach2, but its benefits diminish as time to treatment increases3. Staff shortages due to illness, quarantining and emergency redeployment further complicate the issue.

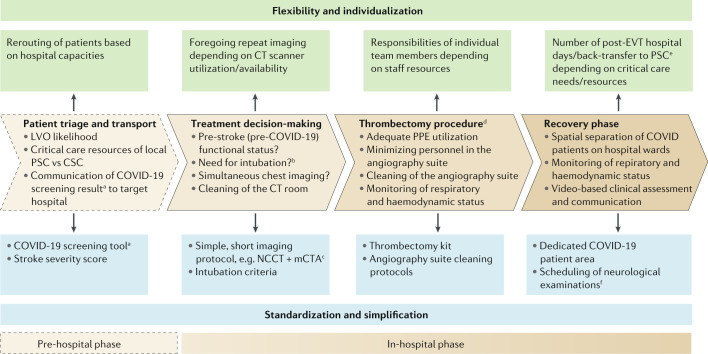

Two recent articles from the University of Cincinnati (Smith et al.4) and the Society of Vascular and Interventional Neurology (Nguyen et al.5) provide concrete guidance on how to minimize delays to EVT while keeping the risk of infectious exposure for patients and staff at a minimum. Specific workflow steps might vary depending on the local set-up, but the articles emphasize six key principles to ensure safe and timely EVT in the COVID-19 era: transfer of key knowledge, clinical practice, standardization and simplification, individualization, flexibility and teamwork (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. COVID-19-related challenges in EVT workflows.

The figure illustrates how the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to influence endovascular treatment (EVT) for acute ischaemic stroke in the pre-hospital and in-hospital phases. CSC, comprehensive stroke centre; LVO, large vessel occlusion; mCTA, multiphase CT angiography; NCCT, non-contrast CT; PPE, personal protective equipment; PSC, primary stroke centre. aSee first figure in ref.4. bSee second figure in ref.4. cAs described and used in previous trials7–9. dFor a detailed description of EVT workflows in the neuroangiography suite, see ref.4. eSee ‘Postacute care’ section in ref.5. fPost-EVT neurological assessment schedule as proposed in ref.4.

The COVID-19 pandemic requires fast and flexible reallocation of hospital staff and resources. To seamlessly integrate new staff into existing stroke teams, new team members must be taught the key knowledge that is necessary for acute stroke treatment and infectious disease control, for example, how to screen patients for COVID-19 symptoms, as summarized in a figure in the Smith et al. paper4, and how to administer intravenous thrombolysis.

The COVID-19 pandemic requires fast and flexible reallocation of hospital staff and resources

Smith et al.4 describe a range of workflow changes in stroke treatment — in particular, mechanical thrombectomy — that are required during the COVID-19 pandemic, including additional personal protective equipment (PPE) and respiratory screening measures. Such changes often lead to uncertainty among the members of the stroke team. Rehearsing COVID-19 stroke workflows, such as through simulation training, is crucial to effectively identify safety threats and familiarize the stroke team with COVID-19-related workflow changes, such as donning and doffing of PPE, thereby minimizing treatment delays6. Nguyen and colleagues suggest that an observer should watch team members don and doff their gown and PPE to identify potential breaches in viral protection5.

To minimize confusion and treatment delays, imaging protocols and workflow steps should be as standardized and simple as possible, as outlined in an algorithm in the paper by Smith et al.4. For example, standardized criteria for intubation prior to EVT help to avoid discussions and minimize treatment delays4. Nguyen et al. suggest designating a COVID-19 neuroangiography suite in which all stroke patients with suspected and/or confirmed COVID-19 are treated5. The thrombectomy procedure itself should also be standardized, with a pre-prepared thrombectomy kit readily available, to reduce the cognitive load for operators, technicians and nurses.

Hospital set-ups, health-care infrastructures and resources are unique to each centre; thus, workflows and responsibilities of health-care workers will vary. Consequently, protocols need to be individualized according to the local circumstances. For example, large hospitals could have a dedicated CT scanner for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, as described by Smith et al.4. In smaller hospitals, such spatial separation might not be possible, so additional precautions will be necessary to protect other patients.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a rapidly evolving situation with infection rates, staff resources and availability of hospital beds and PPE constantly changing. Stroke workflows and post-stroke care strategies need to be flexible and adapt to new developments and available resources, as both articles point out. If the COVID-19 caseload on the stroke unit of a particular hospital exceeds the staff capacity, for instance, it will become necessary to alter pre-hospital transport paradigms and reroute acute stroke patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection to another, more distant hospital.

The physical and mental strain on health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic is substantial, and teamwork is crucial to alleviate stress and avoid burnout. Nguyen and colleagues emphasize that frontline health-care workers are particularly vulnerable to depression and anxiety5. Open communication, a non-judgmental atmosphere and a willingness to listen to problems and concerns of colleagues are important to build trust among team members and facilitate smooth integration of new staff into existing teams.

The physical and mental strain on health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic is substantial

In conclusion, acute ischaemic stroke is a highly time-dependent condition, and the rapid initiation of treatment remains vital in the COVID-19 era. In their articles, Nguyen et al. and Smith et al. highlight the challenges that stroke teams encounter when trying to balance the risk of infectious exposure for health-care workers and patients against the available resources and the need for timely EVT4,5. Herein, we have outlined six key principles that can help to ensure timely and safe EVT while minimizing infectious exposure of staff and patients. However, as both articles acknowledge, the specific steps of the COVID-19 EVT workflow will vary according to local infrastructures and resources and will need to change over time as the COVID-19 situation evolves.

Competing interests

J.M.O. is supported by the Julia Bangerter Rhyner Foundation, University of Basel Research Foundation and Freiwillige Akademische Gesellschaft Basel. M.G. is a consultant for Medtronic, Stryker, Microvention, GE Healthcare and Mentice.

References

- 1.Oxley TJ, et al. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid-19 in the young. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goyal M, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;387:1723–1731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00163-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saver JL, et al. Time to treatment with endovascular thrombectomy and outcomes from ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:1279–1288. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.13647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith MS, et al. Endovascular therapy for patients with acute ischemic stroke during the COVID-19 pandemic: a proposed algorithm. Stroke. 2020 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.029863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen TN, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic: emergency preparedness for neuroscience teams: a guidance statement from the Society of Vascular and Interventional Neurology. Stroke. 2020 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurz M, O. J., Daehli-Kurz, K. & Goyal, M. Improving stroke care in times of the COVID-19 pandemic through simulation: practice your protocols! Stroke (in the press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Goyal M, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:1019–1030. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill MD, et al. Efficacy and safety of nerinetide for the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke (ESCAPE-NA1): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;395:878–887. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menon BK, et al. Multiphase CT angiography: a new tool for the imaging triage of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Radiology. 2015;275:510–520. doi: 10.1148/radiol.15142256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]