To the Editor

The gastrointestinal tract is the largest lymphoid organ in the body. One of the major functions of the gastrointestinal tract is maintaining of the balance between active immunity, tolerance and immunosuppression. Dysregulation of this physiologic process can lead to diseases such as food allergy, celiac disease (CD) or inflammatory bowel disease [1]. Therefore, gastrointestinal symptoms such as chronic diarrhea and malabsorption might be indicative of primary immunodeficiency diseases [1].

A 10-year-old girl referred to our clinic with a six-year history of chronic watery diarrhea and unresponsiveness to a gluten free diet. She had been evaluated and treated previously for chronic diarrhea, intermittent fever, recurrent pneumonia, candida esophagitis, pancytopenia, hypoalbuminemia, hypolipidemia, vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiencies. She was diagnosed with CD, based on serologic and histopathological findings. She was placed on a strict gluten free diet for a year, but diarrhea did not improve. She has two healthy brothers. Her parents were consanguineous. On physical examination, she was cachectic; with height for age below 3 % (height SDS −5.18) and weight for age below 3 % (weight SDS −5.27). Bone age and height age of the patient were 6 years, 10 months and 5 years, 3 months, respectively. She had protuberant abdomen and clubbing. Liver and spleen were palpable at 1 cm and 4 cm below the costal margins. Laboratory tests revealed mildly increased liver transaminases. Hemoglobin was 8.32 g/dl; MCV, 85 fL; RDW, 23.4 %; white blood cell, 5570/mm3; platelet, 230,000/mm3; reticulocyte count, 1 % and ferritin, 2.8 ng/ml. Coombs test was negative. Sedimentation rate was 18 mm/h, C-reactive protein, 1.78 mg/dl. Stool examinations were normal. 25-hydroxi vitamin D level was 25.7 ng/ml. Insulin like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) was 3.5 ng/mL (Normal, 108–648 ng/mL) and insulin like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP-3), 580 ng/mL (Normal, 2690–7200 ng/mL). Stimulated IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 were 2.85 ng/mL and 720 ng/mL, respectively, both markedly reduced. Basal and stimulated growth hormone levels were compatible with growth hormone insensitivity (12.9 ng/mL and 9.79 ng/mL, respectively). Anti-tissue transglutaminase IgA was positive with a titer of 200 IU/ml. Thyroid auto-antibodies, anti-saccharomyces cerevicea antibody and pANCA were negative. Bone mineral density showed severe osteoporosis (Z score, −5). Chest X-ray showed reticular density in the parenchyma of the lung. High-resolution chest tomography showed bilateral tubular bronchiectasis. Smear staining for acid resistant bacteria and tuberculosis PCR, and culture were negative. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examination revealed scalloping in the duodenal mucosa. Colonoscopy showed nonspecific nodularity in the colon mucosa. Histopathological examination of duodenum revealed total villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia and intraepithelial lymphocytosis. Biopsies of the other parts of the gastrointestinal tract demonstrated mild reflux esophagitis, chronic active gastritis and focal cryptitis in the colon. She suffered from sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, severe dehydration, metabolic acidosis, severe electrolyte imbalance and renal tubulopathy. Her clinical findings were improved by antibiotherapy and intravenous fluid therapy. Oral prednisone was started with the diagnosis of refractory CD, but she was not responsive.

Immunologic investigation was undertaken for primary immunodeficiency disease because of her chronic diarrhea, celiac antibody positivity, celiac-like mucosal findings, recurrent pulmonary infections with bronchiectasis, severe sepsis and severe growth retardation.

Immunological evaluation revealed normal IgG, elevated IgA and slightly decreased IgM levels with normal isohemagglutinin titer, normal T, B, NK cell counts and normal activation response to PHA and anti-CD3 (Tables 1 and 2 in supplementary data). She has slightly decreased switched memory B cells.

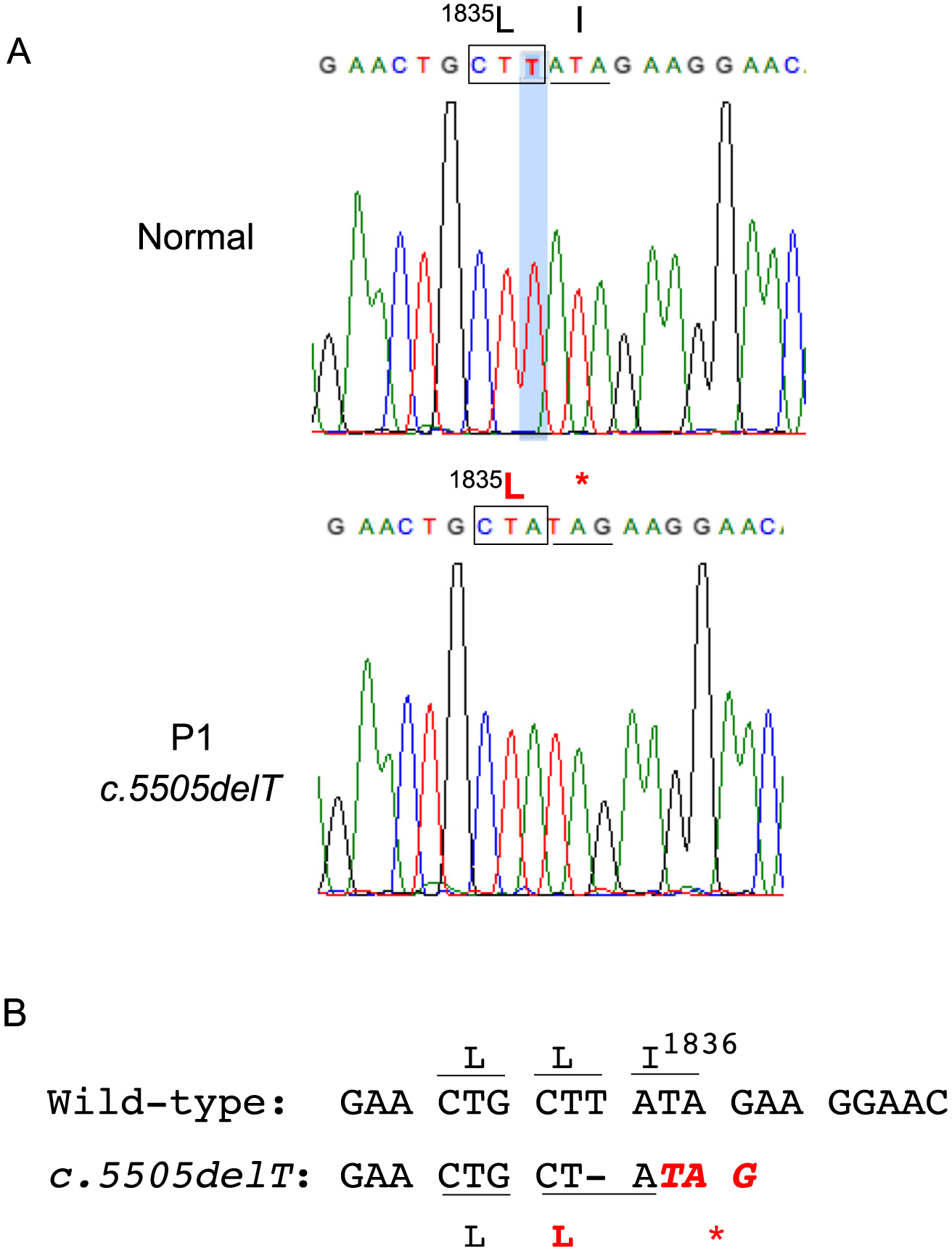

In light of the clinical and biochemical findings, initial genetic studies focused on sequencing the gene for STAT5B, which proved to be wild type. A novel homozygous frameshift mutation in the LRBA-gene c.5505delT (p.Ile1836*) was highlighted as the causal variant in whole exome sequencing analysis (Fig. 1). Sanger sequencing confirmed this variant to be homozygous in the patient and absent in the unaffected brother (Family Studies and Gene Analysis in Supplementary data).

Fig. 1.

Homozygous frameshift mutation in the LRBA-gene c.5505delT (p.Ile1836*). A. Electropherogram showing c.5505delT; B. Loss of c.5505 T causes a frameshift, which does not alter Leu1835 but results in predicted early protein termination at the adjacent amino residue p.Ile1836*

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

As she has HLA fully matched healthy sibling donor and multiple organ dysfunction (bronchiectasis, tubulopathy and severe colitis), a novel non-myeloablative conditioning regimen consisting of BU/Flu/ATG [2], was applied. She received 8 × 106 peripheral blood CD34+cells/kg from her brother. CsA (−1) and methotrexate (+1,+3, +6) was used for GvHD prophylaxis. The early post-transplantation period was uncomplicated and she was discharged at +37. She has herpes zoster at +5 mo. treated with acyclovir. She is now 1 year post-transplant, with 97 % donor chimerism. Her health improved markedly, with an increased growth velocity (15 kg/ year and 10 cm/year) following the HSCT.

Discussion

Celiac disease is a chronic immune mediated enteropathy precipitated by exposure to dietary gluten in genetically predisposed people [3]. CD is associated with autoantibody positivity, HLA-DQ2 or DQ8 and typical histological findings including increasing intraepithelial lymphocytes, crypt hypertrophy and villous atrophy [3]. Treatment of the disease is strict life-long gluten-free diet and most of the CD patients respond well to this diet. In patients who respond poorly to gluten free diet, issues of non-compliance to the gluten-free diet, refractory CD (persistent or recurrent malabsorption symptoms and signs with villous atrophy despite a strict gluten-free diet for more than 12 months (3)) or other possible disorders with similar histopathological findings, should be considered. In children compliant to gluten free diet, differential diagnosis of refractory CD should include autoimmune enteropathy and primary immunodeficiency syndromes.

Here, we describe LRBA deficiency in a Turkish girl who presented with refractory CD, severe malnutrition, growth hormone insensitivity, chronic pulmonary infection, bronchiectasis, osteoporosis, severe tubulopathy and with slightly decreased IgM levels.

Recent reports demonstrate that deleterious mutations of LRBA cause CVID and autoimmunity, and are associated with inflammation [4–6]. The manifestations of LRBA deficiency include hypogammaglobulinemia due to defective B-cell differentiation, recurrent infections and various autoimmune disorders, such as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, autoimmune thyroiditis, type-1 diabetes, and inflammatory bowel diseases. Other clinical presentations may include severe growth retardation and failure to thrive, growth hormone deficiency, asthma, monoarthritis, seizures, granulomatous infiltration, finger clubbing, hepatosplenomegaly, allergic dermatitis, and nephrotic syndrome. The LRBA gene encodes a large broadly expressed protein that is involved in intracellular vesicle trafficking [7], and, interestingly, it was recently reported that LRBA deficiency was associated with loss of CTLA4, a potent inhibitory immune receptor [8]. Only twenty-five cases of LRBA deficiency have been published to date [4–6, 8–11].

Celiac like histopathological findings, inflammatory bowel disease-like manifestations and autoimmune enteropathy were reported in 11 out of 16 patients with LRBA deficiency [4–6, 9, 10]. These symptoms were associated with unresponsiveness to gluten free diet and corticosteroids as observed in our patient.

Immunological evaluation of our patient revealed normal IgG, IgA and slightly decreased IgM level with normal T, B, NK cell numbers, normal isohemagglutinin titer, normal B cell subsets and normal activation response to PHA and anti-CD3. Immunological picture of LRBA deficiency has been described as CVID, CID, ALPS-like or IPEX-like in published reports [4, 5, 9, 11]. These patients also presented with autoimmunity. Metabolic dysfunction and increased apoptosis of Treg cells have been hypothesized as a key mechanism in the development of humoral autoimmunity in patients with LRBA deficiency [9].

As LRBA is highly expressed in immune cells [4]. HSCT seems to be a viable therapeutic option for these patients. The only published case of HSCT in LRBA deficiency was a 19-year-old patient with ALPS-like phenotype [11]. He received allogeneic HLA–identical stem cells from his mother after conditioning consisting of Flu/ATG/Mel and engrafted successfully, but after 4 years of transplantation idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura relapsed and he needed immuno-suppressive treatment. A successful, uncomplicated transplantation was achieved in our patient with non-myeloablative conditioning although she has multi-organ dysfunction. She is 1 year post-transplant with full donor chimerism and excellent clinical improvement. She will continue to be monitored.

In conclusion, LRBA deficiency should be considered in patients with either combined immunodeficiency or CVID, as well as in children with refractory celiac disease, early-onset colitis and autoimmunity. HSCT following non-myeloablative conditioning regimens appears to be a viable treatment option for these patients. Long-term follow-up and identification of more patients with LRBA mutations will provide valuable insights into the full phenotypic spectrum as well as the treatment options.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10875-015-0220-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Kobrynski LJ, Mayer L. Diagnosis and treatment of primary immunodeficiency disease in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. Clin Immunol. 2011;139(3):238–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gungor T, Teira P, Slatter M, Stussi G, Stepensky P, Moshous D, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning and HLA-matched haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation in patients with chronic granulomatous disease: a prospective multicentre study. Lancet. 2014;383(9915):436–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ludvigsson JF, Leffler DA, Bai JC, Biagi F, Fasano A, Green PH, et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut. 2013;62(1):43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopez-Herrera G, Tampella G, Pan-Hammarstrom Q, Herholz P, Trujillo-Vargas CM, Phadwal K, et al. Deleterious mutations in LRBA are associated with a syndrome of immune deficiency and autoimmunity. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(6):986–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alangari A, Alsultan A, Adly N, Massaad MJ, Kiani IS, Aljebreen A, et al. LPS-responsive beige-like anchor (LRBA) gene mutation in a family with inflammatory bowel disease and combined immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(2):481–8 e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns SO, Zenner HL, Plagnol V, Curtis J, Mok K, Eisenhut M, et al. LRBA gene deletion in a patient presenting with autoimmunity without hypogammaglobulinemia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(6):1428–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang JW, Lockey RF. Lipoplysaccharide-responsve beige-like anchor (LRBA) a novel regulator of human immune disorders. Austin J of Clin. Immunol 2014;1(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo B, Zhang K, Lu W, Zheng L, Zhang Q, Kanellopoulou C, et al. AUTOIMMUNE DISEASE. Patients with LRBA deficiency show CTLA4 loss and immune dysregulation responsive to abatacept therapy. Science. 2015;349(6246):436–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charbonnier LM, Janssen E, Chou J, Ohsumi TK, Keles S, Hsu JT, et al. Regulatory T-cell deficiency and immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked-like disorder caused by loss-of-function mutations in LRBA. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(1):217–27 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serwas NK, Kansu A, Santos-Valente E, Kuloglu Z, Demir A, Yaman A, et al. Atypical manifestation of LRBA deficiency with predominant IBD-like phenotype. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(1): 40–7 e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seidel MG, Hirschmugl T, Gamez-Diaz L, Schwinger W, Serwas N, Deutschmann A, et al. Long-term remission after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in LPS-responsive beige-like anchor (LRBA) deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.