Endoscopy room personnel are at risk of contracting coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), because gastrointestinal endoscopy is an aerosol-generating procedure; COVID-19 is present in the gastrointestinal tract and in stool,1 and studies indicate its viability in aerosols.2 Nonessential procedures have been deferred based on guidance3 , 4 to preserve hospital resources for patients with COVID-19, limit the spread of the virus within hospitals, and conserve limited supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE). Endoscopy units have undertaken significant but varied additional measures to maximize safety.

Methods

An online survey comprising 50 questions was e-mailed to US gastroenterologists; it was designed to evaluate the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on endoscopy units/personnel and to determine institutional responses (see Supplementary Methods). The 2-week survey was closed on May 10, 2020.

Results

A summary of survey responses is depicted in Supplementary Table 1.

Institutional Characteristics

A total of 407 responses were received from 276 centers in 42 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. After excluding duplicate responses from unique centers, 141/276 (51.1%) respondents reported practicing in University/University-affiliated centers while 135/276 (48.9%) reported practicing in facilities without University affiliation.

Institutional Pandemic-Related Responses

Most centers developed a formal COVID-19 mitigation protocol (135/276, 87%) and implemented a tiered, urgency-based scheduling system (243/276, 88%). Redeployment of gastroenterologists to support internal medicine/intensive care units is being considered by 173 of 276 (63%) and 104 of 276 (38%) of centers, respectively; a higher proportion of US Northeast centers are considering redeployment, compared to centers in the US South, Midwest, and West (82% vs 61% vs 57.1% vs 56.5%, respectively; P = .008).

Impact on Procedural Volume

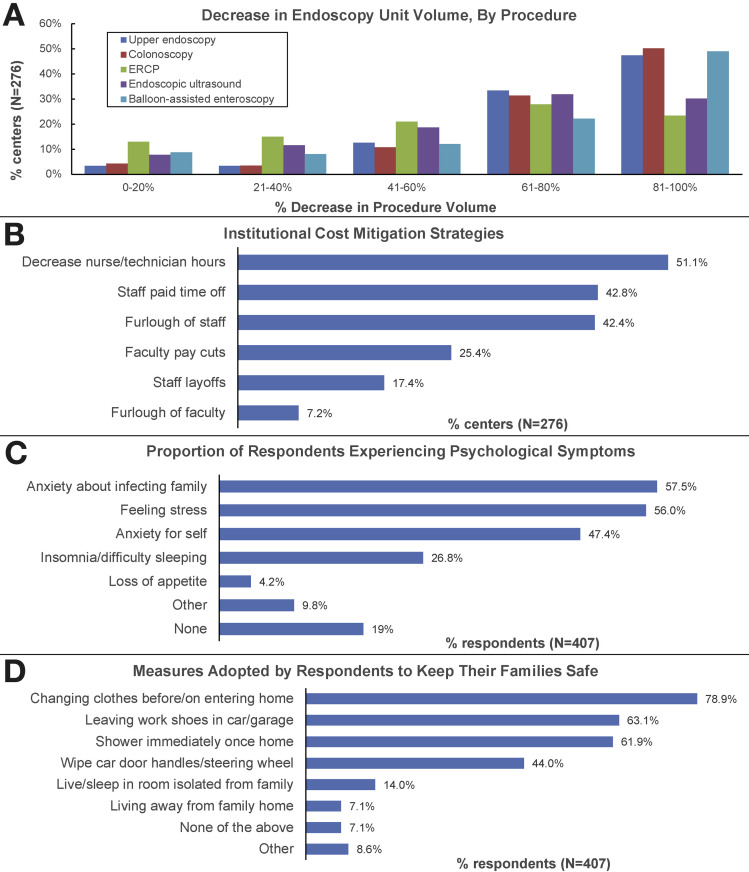

Procedural volumes fell significantly for upper endoscopy, colonoscopy, and deep enteroscopy, with 81%, 82%, and 71% of centers, respectively, reporting a >60% decrease in volume. For endoscopic ultrasonography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, 62% and 51% of centers respectively reported a greater than 60% decrease in procedure volume (Figure 1 A).

Figure 1.

(A) Decrease in endoscopy unit volume, by procedure. (B) Institutional cost mitigation strategies. (C) Proportion of respondents experiencing psychological symptoms. (D) Measures adopted by respondents to keep their families safe. ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatograpy.

Impact on Provider Salary

A total of 97 of 276 centers (35%) indicated that provider salary would be preserved; 55 of 276 (20%) indicated that salary would be preserved at the preceding year’s level. A total of 91 of 407 (22%) respondents from 70 of 276 (25%) institutions reported that faculty would receive pay cuts. Institutional cost mitigation strategies are depicted in Figure 1 B.

Impact on Education of Trainees

Gastroenterology/nursing/technician trainees were excluded from participating in procedures in 169 of 276 centers (61%), with 26.4% of centers excluding advanced endoscopy fellows.

Coronavirus Disease 2019 Testing

More than half (143 of 276, 52%) of centers performed COVID-19 testing on all patients before endoscopy. Endoscopy on patients with confirmed/high suspicion for COVID-19 is performed in negative-pressure endoscopy or operating rooms in 187 of 276 (68%) of centers.

Personal Protective Equipment Use

N95 respirators were approved for all endoscopic procedures in 220 of 276 (80%) of institutions. Respondents from 128 of 276 (46%) of centers reported receiving a single N95 respirator per day. N95 respirators are reused after sterilization at 134 of 276 (49%) of centers, with 79 of 276 (29%) reusing respirators after an extended period of holding.

Stressors and Psychological Symptoms Among Respondents

Inadvertent exposure to COVID-19–positive patients/staff was reported by 65 of 407 (16%) respondents and was more likely among trainee than nontrainee physicians (29% vs 14%; odds ratio [OR], 2.5; 95% CI, 1.36–4.63; P = .003). Thirty-nine (10%) respondents developed symptoms that prompted testing for COVID-19; 6 of 407 (1.5%) tested positive.

A large majority of respondents (330/407, 81%) reported psychological symptoms (Figure 1 C). A high level of concern regarding being infected with COVID-19 at work was reported by 74 of 407 (18%) respondents, and 145 of 470 (35%) reported a high level of concern about inadvertently infecting family members. Measures adopted by respondents to keep their family members safe are depicted in Figure 1 D. Feeling that supply issues led to a delay in implementing N95 respirator use was associated with experiencing psychological symptoms (OR, 2.08; 95% CI 1.23–3.53; P = .006), as was planned institutional implementation of cost mitigation strategies (OR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.11–3.97; P = .017).

Impact of Type of Institution on Infrastructure and Responses

Data are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Discussion

The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the unpreparedness of most countries, including the United States, in responding to pandemics, and the fragility of global supply chains in times of global crisis. Nevertheless, at this stage of the pandemic, the response of the majority of US institutions appears to be robust. The vast majority of endoscopy centers have instituted tier-based endoscopy scheduling and have created formal mitigation protocols for COVID-19, including PPE policies and preprocedural testing of patients for COVID-19.

Striking decreases in procedural volume have been noted, allowing consolidation of endoscopist schedules. This fall in volume has affected endoscopy center revenues, triggering institutional cost-containment strategies.

Education of gastroenterology, nurse, and technician trainees has been affected because of exclusion from endoscopic procedures. Concerningly, a quarter of institutions have excluded advanced endoscopy fellows from procedures. This will have a disproportionate negative impact on their training, given the brevity of the 1-year advanced endoscopy fellowship.

The psychological well-being of endoscopy unit personnel has been buffeted by several stressors, predominantly related to the risk of acquiring infection at the workplace and transmitting this to loved ones at home. PPE shortage, particularly of N95 respirators, has been a source of considerable anxiety. Although approved for use during endoscopy by most institutions by mid-April, limited supply has led institutions to pursue extended use, reuse, recycling, and even reprocessing of N95 respirators, despite concerns regarding the impact of reprocessing on their structural integrity/efficacy.5 Additional potential sources of distress include institutional plans to deploy gastroenterologists to support internal medicine/intensive care activities and looming salary cuts/furloughs. Overall, a higher proportion of our respondents reported stress and anxiety than documented in a survey of front-line health care workers in Wuhan.6

Our midpandemic survey indicates a robust response within the majority of US endoscopy centers; essential elements including N95 respirator use and patient testing for COVID-19 have been implemented that will facilitate re-expansion of procedural indications for endoscopy.7 , 8 The impact of the pandemic on training, particularly of advanced endoscopy fellows, is concerning and should be addressed. Finally, the impact of the pandemic on the psychological health of endoscopy unit personnel should not be underestimated; in addition to improving access to information, PPE, and COVID-19 testing, institutions should work to support their personnel emotionally, psychologically, and financially.

Acknowledgments

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Sharareh Moraveji, MD (Conceptualization: Supporting; Data curation: Equal; Formal analysis: Supporting; Methodology: Equal; Project administration: Lead; Software: Lead; Writing – original draft: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal); Adarsh M. Thaker, MD (Data curation: Equal; Formal analysis: Lead; Methodology: Supporting; Validation: Equal; Writing – original draft: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal); Venkatara Raman Muthusamy, MD (Data curation: Equal; Formal analysis: Supporting; Methodology: Equal; Supervision: Equal; Validation: Equal; Writing –original draft: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Equal); Subhas Banerjee, MD (Conceptualization: Lead; Data curation: Equal; Formal analysis: Equal; Methodology: Lead; Software: Equal; Supervision: Lead; Validation: Equal; Writing – original draft: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Lead).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.061.

Supplementary Methods

Survey Instrument

An online survey was developed by 2 advanced endoscopists (SB, SM) to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on US endoscopy units. The survey comprised 50 questions and was designed to be completed within 10 minutes. The survey was designed to collect data on respondent demographics, institutional characteristics and infrastructure, procedural and periprocedural practices, PPE use, psychological well-being, and financial issues. The survey was then reviewed by 2 additional advanced endoscopists (VRM, AMT) and modified for clarity and appropriateness.

Survey Distribution

A direct link to the online survey instrument (Survey Monkey, Palo Alto, CA) was distributed via e-mail to gastroenterologists by using a previously described database with 1600 current contacts5 and to gastroenterologists personally known to the authors (n = 200). To broaden the respondent pool to include all endoscopy unit personnel, e-mail recipients were asked to forward the e-mails to their fellows and to endoscopy unit nurses and technicians. Reminder e-mails were sent out a week later. The survey was opened on April 26 and closed 2 weeks later, on May 10, 2020.

Data were collected anonymously except for institution name, state, and zip code to identify duplicate responses from the same institution. Physician unit director responses were prioritized for inclusion, followed by the most recent physician response, trainee response, and then nurse/staff response in the case of duplicate responses from any given center. Zip code data were used in assigning endoscopy units to geographic regions based on US Census Bureau definitions.

The data were analyzed for differences in endoscopy unit practices, personal experiences, and opinions among practice settings and regions. Analyses were conducted on a per-institution basis or a per-respondent basis, as appropriate for the particular analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with JMP Software (JMP, version 5; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Pearson chi-square testing was used to compare differences between the 2 groups using categorical variables.

Supplementary Table 1.

Summary of Survey Responses on a Per-Center and Per-Respondent Basis

| Survey responses: center based | Centers, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total centers | 276 (100) | |

| Region of responding centers | ||

| Midwest | 42 (15.2) | |

| Northeast | 61 (22.1) | |

| South | 79 (28.6) | |

| West | 92 (33.3) | |

| Not reported | 2 (0.7) | |

| Practice settinga | ||

| University hospital | 101 (36.6) | |

| University affiliated | 54 (19.6) | |

| Hospital—not university affiliated | 91 (33) | |

| Freestanding ambulatory center | 79 (28.6) | |

| Other | 12 (4.3) | |

| Negative pressure endoscopy rooms | ||

| Yes | 135 (48.9) | |

| No | 113 (40.9) | |

| Do not know | 26 (9.4) | |

| Not reported | 2 (0.7) | |

| Location of endoscopic procedures for patients positive for or with high suspicion for COVID-19a | ||

| Standard endoscopy room | 42 (15.2) | |

| Negative pressure endoscopy room | 105 (38) | |

| Standard operating room | 11 (4) | |

| Negative pressure operating room | 82 (29.7) | |

| Don’t know | 61 (22.1) | |

| COVID-19 screening and testing | ||

| Prescheduling COVID-19 symptom screening | ||

| Yes | 263 (95.3) | |

| No | 6 (2.2) | |

| Don’t know | 4 (1.4) | |

| Not reported | 3 (1.1) | |

| Onsite COVID-19 testing | ||

| Yes | 212 (76.8) | |

| No | 52 (18.8) | |

| Don’t know | 10 (3.6) | |

| Not reported | 2 (0.7) | |

| Preprocedure COVID-19 testing | ||

| Only in patients with concerning history and/or symptoms | 47 (17) | |

| All patients | 143 (51.8) | |

| Not performed—symptomatic patients not scheduled | 50 (18.1) | |

| Don’t know | 8 (2.9) | |

| Other | 27 (9.8) | |

| Not reported | 1 (0.4) | |

| Criteria to test health care workersa | ||

| Any asymptomatic worker on request | 48 (17) | |

| Asymptomatic workers with exposure to patients with COVID-19 | 104 (37.7) | |

| Flu-like symptoms alone are sufficient to be tested | 125 (45.3) | |

| Must have cough/SOB + fever | 79 (28.6) | |

| N95 and PPE use, mitigation of infection risk | ||

| Institutional policy for use of N95 respirators | ||

| Approved for all endoscopic procedures | 220 (79.7) | |

| Only for known patients with COVID-19 and high-risk patients with pending test | 35 (12.7) | |

| Approved for upper endoscopic procedures only | 11 (4) | |

| N95 not approved for any endoscopic procedures | 6 (2.2) | |

| Not reported | 4 (1.4) | |

| Implementation of N95 respirator use for endoscopic procedures | ||

| Before March 15 | 27 (9.8) | |

| March 16–31 | 120 (43.5) | |

| April 1–15 | 70 (25.4) | |

| April 16 to present | 33 (12) | |

| Other/don’t know | 14 (5.1) | |

| Not reported | 12 (4.3) | |

| Staff re-education in donning/doffing of PPE | ||

| Yes | 239 (86.6) | |

| No | 23 (8.3) | |

| Don’t know | 13 (4.7) | |

| Not reported | 1 (0.4) | |

| Frequency of N95 respirator distribution to endoscopy providers/staff | ||

| None | 7 (2.5) | |

| One per procedure | 16 (5.8) | |

| One per day | 128 (46.4) | |

| One per week or ∼5 uses | 62 (22.5) | |

| Until soiled or damaged | 11 (4) | |

| Don’t know | 19 (6.9) | |

| Other | 18 (6.5) | |

| Not reported | 15 (5.4) | |

| N95 respirator preservation strategies considereda | ||

| Extended use (use of same mask all day–continued use without removal between procedures) | 138 (50) | |

| Reuse (use of same mask all day but donning and doffing between procedures) | 150 (54.3) | |

| Reuse after decontamination/sterilization of masks | 134 (48.6) | |

| Recycling of masks (recycling of previously used masks after holding them for several days) | 79 (28.6) | |

| N/A | 15 (5) | |

| Interval between N95 respirator reuses if no decontamination/sterilization undertaken | ||

| Less than 4 days | 56 (20.3) | |

| 4–6 days | 49 (17.8) | |

| 7 days or more | 31 (11.2) | |

| Not applicable | 129 (46.7) | |

| Not reported | 11 (4) | |

| Method for decontamination/sterilization of N95 respirators for reusea | ||

| UV light | 57 (20.7) | |

| Hydrogen peroxide | 51 (18.5) | |

| Ethylene oxide | 9 (3.3) | |

| Moist heat | 4 (1.4) | |

| Other | 4 (1.4) | |

| Not applicable | 70 (25.4) | |

| Don’t know | 82 (29.7) | |

| Staff PPE during procedures on patients with low concern for COVID-19a | ||

| N95 masks | 232 (84.1) | |

| CAPR/PAPR | 33 (12) | |

| Surgical masks | 176 (63.8) | |

| Eye shields/goggles/face shields | 260 (94.2) | |

| Gowns | 263 (95.3) | |

| Hazmat suits | 5 (1.8) | |

| Double gloving | 152 (55.1) | |

| PPE use during procedures on patients with positive COVID-19 result or high concerna | ||

| N95 masks | 226 (81.9) | |

| CAPR/PAPR | 70 (25.4) | |

| Surgical masks | 133 (48.2) | |

| Eye shields/goggles/face shields | 228 (82.6) | |

| Gowns | 220 (79.7) | |

| Hazmat suits | 23 (8.3) | |

| Double gloving | 173 (62.7) | |

| Minimizing endoscopic irrigation | ||

| Yes | 48 (17.4) | |

| No | 180 (65.2) | |

| Not applicable—Don’t perform procedure | 46 (16.7) | |

| Not reported | 2 (0.7) | |

| Survey responses: respondent based | Respondents, n (%) | |

| Total respondents | 407 (100) | |

| Role 1 | ||

| Physician | 309 (75.9) | |

| General GI fellow | 61 (15) | |

| Advanced endoscopy fellow | 5 (1.2) | |

| Nurse (ie, RN, APRN, LPN, CGRN) | 19 (4.7) | |

| Nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant | 10 (2.5) | |

| Other administrative role in endoscopy unit | 3 (0.7) | |

| Role 2 | ||

| Advanced/therapeutic endoscopy | 170 (41.8) | |

| General GI endoscopy | 202 (49.6) | |

| N/A–not an endoscopist | 16 (3.9) | |

| Not reported | 19 (4.7) | |

| Region of employment of individual respondents | ||

| Midwest | 67 (16.5) | |

| Northeast | 77 (18.9) | |

| South | 93 (22.9) | |

| West | 152 (37.3) | |

| Not reported | 18 (4.4) | |

| Feel that N95 masks or other PPE are in short supply at institution | ||

| Yes | 201 (49.4) | |

| No | 176 (43.2) | |

| Don’t know | 11 (2.7) | |

| Not reported | 19 (4.7) | |

| Believe there was a delay in N95 use for endoscopy at center because of limited supply | ||

| Yes | 177 (43.5) | |

| No | 177 (43.5) | |

| Don’t know | 31 (7.6) | |

| Not reported | 22 (5.4) | |

| Inadvertently exposed to COVID-19–positive patient/s or staff | ||

| Yes | 65 (16) | |

| No | 210 (51.6) | |

| Don’t know | 110 (27) | |

| Not reported | 22 (5.4) | |

| Developed symptoms that prompted testing for COVID-19 | ||

| Yes | 39 (9.6) | |

| No | 345 (84.7) | |

| Not reported | 23 (5.7) | |

| Concern about being infected or reinfected with COVID-19 at work? | ||

| Low level of concern | 116 (28.5) | |

| Moderately concerned | 211 (51.8) | |

| Very concerned | 74 (18.2) | |

| Not reported | 6 (1.5) | |

| Tested positive for COVID-19 | ||

| Yes | 6 (1.5) | |

| No | 197 (48.4) | |

| Not tested | 197 (48.4) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.25) | |

| Not reported | 6 (1.5) | |

| Concern about inadvertently infecting family members during pandemic | ||

| Low level of concern | 85 (20.9) | |

| Moderately concerned | 169 (41.5) | |

| Very concerned | 145 (35.6) | |

| Not reported | 8 (2) | |

APRN, advanced practice registered nurse; CAPR, controlled air purifying respirator; CGRN, certified gastroenterology registered nurse; GI, gastrointestinal; LPN, licensed practical nurse; N/A, not applicable; PAPR, powered air purifying respirator; RN, registered nurse; SOB, shortness of breath; UV, ultraviolet.

Results are non-exclusive.

Supplementary Table 2.

Comparison Between University-Affiliated Centers and Centers Not Affiliated With a University

| Survey Responses | University affiliated, n (%) | Not university affiliated, n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total centers, n | 141 | 135 | — |

| Negative pressure room | 90 (63.8) | 59 (43.7) | .0008 |

| Onsite COVID-19 test | 124 (87.9) | 79 (58.5) | <.0001 |

| Decontamination of N-95 for reuse | 67 (47.5) | 63 (46.7) | .89 |

| Test all patients before procedure | 82 (58.1) | 43 (31.8) | <.0001 |

| Test some or all patients before procedure | 106 (75.2) | 75 (55.6) | .0006 |

| Institution indicated salary preservation | 63 (44.7) | 39 (28.9) | .007 |

| Institution indicated faculty furlough | 9 (6.4) | 14 (10.4) | .23 |

| Institution indicated staff furlough | 48 (34) | 72 (53.3) | .001 |

References

- 1.Xiao F. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1831–1833. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Doremalen N. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-releases-recommendations-adult-elective-surgeries-non-essential-medical-surgical-and-dental. Accessed May 17, 2020.

- 4.https://www.asge.org/home/advanced-education-training/covid-19-asge-updates-for-members/gastroenterology-professional-society-guidance-on-endoscopic-procedures-during-the-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed May 17, 2020.

- 5.Livingston E. JAMA. 2020;19(323):1912–1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du J. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.03.011. [Epub ahead of press] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corral J.E. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:524–534.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han J. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:445–447. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.03.3855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]