We read the article, “Novel approach to reduce transmission of COVID-19 during tracheostomy,” by Foster and colleagues.1 We appreciate the authors’ protocol to reduce the risk of healthcare worker (HCW) infection during most of the surgical procedure; however, based on our experience with Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia patients in one of Italy’s national “hot spots” (Pesaro Civil Hospital, Marche Region), we believe the most dangerous phase for HCW contamination in tracheostomy is the interval between deflation of the endotracheal tube (EET) cuff and the patient’s reconnection to the ventilator through the cuffed tracheostomy cannula (TC).

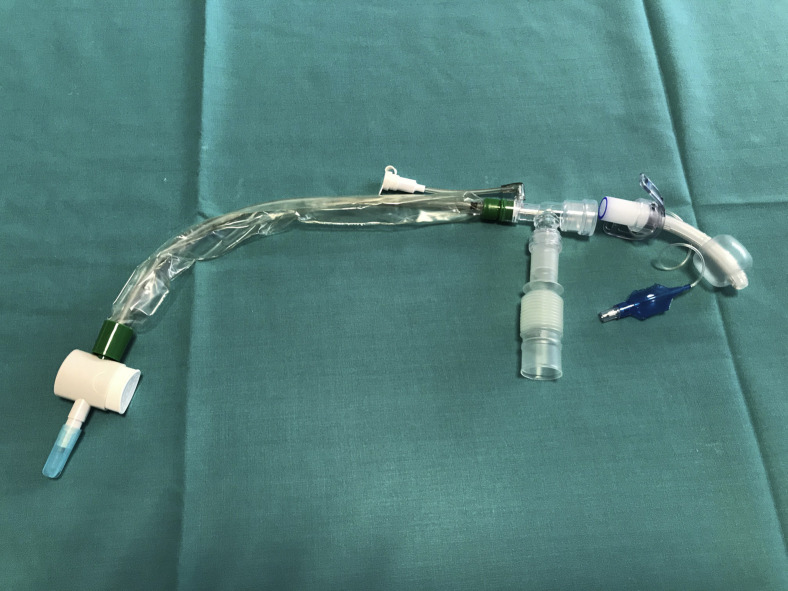

In order to minimize such risk, we propose the following tips. First, advance the EET until its hyperinflated cuff approaches the carina (to avoid cuff damage during tracheal incision) preoperatively. We avoid pushing the EET caudally right before tracheal opening (intraoperatively)2 because this requires a cuff deflation-reinflation maneuver, enhancing the intraoperative risk for contaminated expired air to infect HCWs (anesthesiologist and anesthesiology nurse). Second, adequate pre-oxygenation (100% oxygen for 3 minutes) followed by interruption of mechanical ventilation 30 seconds before tracheal incision (pre-tracheotomy apnea). This step, proposed by Wei and colleagues,2 prevents the expired air to come out under pressure (“champagne effect”) from the patient’s lower airways after EET cuff deflation, with a consequent reduction of HCW contamination risk. Third, a Halyard closed suction system (Halyard Health) is connected to the TC (with its nonfenestrated inner tube already inserted) before tracheal opening (Fig. 1 ) and is attached to the ventilator at the end of surgery. The time interval (air exposure time [AET]) between EET cuff deflation and connection of the cuffed tracheostomy cannula-Halyard system to the ventilator is the most hazardous phase for HCW contamination, because the patient’s lower airways are not entirely “excluded” (not connected to the ventilator system) from the external environment.2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Figure 1.

Halyard closed suction system (Registered Trademark or Trademark of Halyard Health, Inc. or its affiliates. Copyright 2016 HYH) is connected with the tracheostomy cannula before cannula insertion into the trachea.

We quantified this contamination risk by measuring AET in 24 COVID-19 patients (19 M, 5 F), mean age 62.9 ± 11.8 years, submitted to tracheostomy between February 3 and March 25, 2020. The AET for surgical tracheostomy was 5.5 ± 1.5 seconds, less than (p < 0.001) the AET for percutaneous tracheotomies (21.8 ± 5.7 seconds) performed in COVID-19–negative subjects. The use of the Halyard system (connected to the cannula before tracheal opening) not only minimizes AET, but enables immediate aspiration of tracheal/bronchial infected secretions after EET removal through a “closed circuit,” therefore reducing the risk of HCW contamination. As a confirmation, in our case series, no HCW infection has been recorded so far. Last, creation of the Björk tracheal flap, sutured to the overlying skin by 2 single stitches with Vicryl 2/0 (Johnson & Johnson Intl), eases TC insertion/substitution and minimizes HCW contamination risk in the recovery period.

In conclusion, we thank Foster and colleagues1 for their protocol. We believe combining their idea with the tips we have developed, together with having an operating room inside the ICU with negative pressure, a meticulous “clean/contaminated” dressing pathway, and an experienced “COVID-19 airway team,” may be useful for better surgical planning and prevention of HCW infection when performing tracheostomy in patients affected by COVID-19 pneumonia.

Footnotes

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Foster P., Cheung T., Craft P. Novel approach to reduce transmission of COVID-19 during tracheostomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2020 Apr 10 doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.04.014. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei W.I., Tuen H.H., Ng R.W., Lam L.K. Safe tracheostomy for patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1777–1779. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200310000-00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tran K., Cimon K., Severn M. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLos ONE. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison L., Winter S. Guidance for surgical tracheostomy and tracheostomy tube change during the Covid-19 pandemic. http://www.entuk.org/tracheostomy-guidance-during-covid-19-pandemic Available at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Canadian Society of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery . 2020. Recommendations from the CSO-HNS Taskforce on performance of tracheotomy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Available at: https://www.entcanada.org/wp-content/uploads/COVID-19-Guidelines-CSOHNS-Task-Force-Mar-23-2020. Accessed April 13, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim H.J., Ko J.S., Kim T.Y., Scientific Committee on Korean Society of Anesthesiologists Recommendations for anesthesia in patients suspected of Coronavirus 2019-nCoV infection. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2020;73:89–91. doi: 10.4097/kja.20110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]