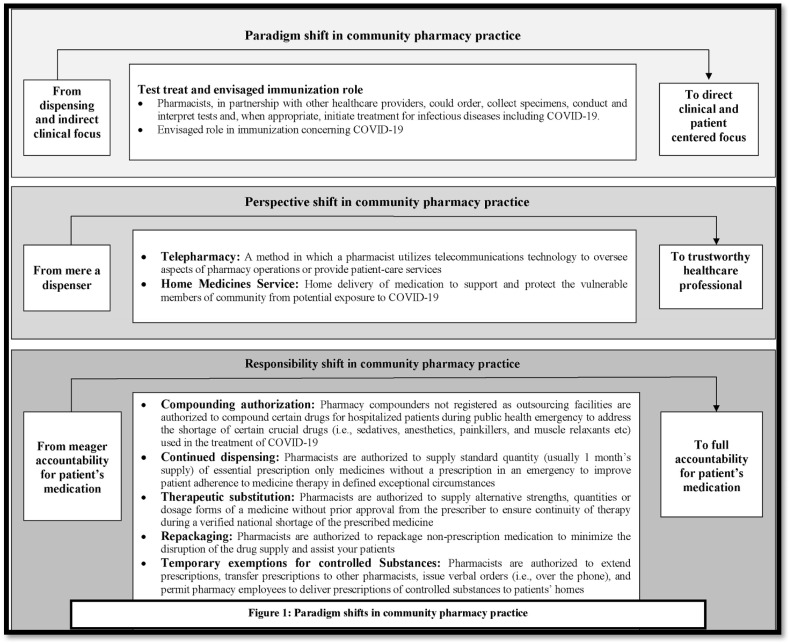

Humanity has always been challenged by the agony associated with pandemics. From Bubonic plague (1347–1351) to the Spanish flu (1918–1919), the world has suffered a great deal in terms of humanistic and monetary loss.1 Likewise, COVID-19 has ravaged the whole world and posed new challenges for the healthcare systems of both developed and developing nations.2 In particular, due to a number of lapses in healthcare systems, developing nations have had difficulty adopting the recommended response strategy − including early detection, prompt isolation and initiation of effective infection prevention and control (IPC) measures; delivery of symptomatic care for those with mild illness; and optimized supportive care for those with severe, and public health quarantine − to flatten the contagion curve. Amidst the abysmally high upsurge of COVID-19 cases worldwide when local, state, and national government and healthcare agencies are searching for strategies to wage the war against pandemic, community pharmacy practice has been gaining momentum and undergoing major paradigm shifts.3 Recognizing the need for fully fledged community pharmacy services, regulatory authorities in many developed countries, such as China, the United Kingdom (UK), the United States (US), Australia. and Canada have waived multiple legislations and published additional guidance for community pharmacies.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 This discussion aims to give overview of the emerging services and flexibilities in pharmaceutical regulations that could shift the paradigm of community pharmacy practice and help community pharmacists move from the bleeding edge to the cutting edge (Fig. 1 ). Moreover, this letter is expected to pique the attention of pharmaceutical regulatory bodies in developing nations towards the potential of community pharmacy services to knock down challenges concerning COVID-19 havoc.

Fig. 1.

Paradgim shifts in community pharmacy practice.

When nations are confronted with an imbalance in the number, distribution of healthcare professionals and inadequate diagnostic facilities in the ongoing COVID havoc, there are increasing debates regarding the envisaged participation of community pharmacists in testing, treatment and immunization of communities. A number of major pharmacy organizations, including American Pharmacists Association (APhA), American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), American Society of Consultant Pharmacists (ASCP) and American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) etc, have recommended that community pharmacists should be authorized “to order, collect specimens, conduct and interpret tests and, when appropriate, initiate treatment for infectious diseases including COVID-19”.9 Realizing the need to expand the availability of rapid testing and reduce unnecessary travel to remote testing sites, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) has permitted pharmacists to conduct COVID-19 tests.8 In conjunction, they are authorized to perform antibody testing which will assist to conclude whether a patient has already healed from the infection, and have immunity to continue.8 Given the recent test authorization, the FDA is expected to approve the forthcoming COVID-19 vaccine to be administered by pharmacist as the benefits of authorizing community pharmacists to assist with vaccination and immunization have been established since the previous influenza pandemic in 2013.9 Authorizing such roles (i.e., test-treat-immunize) will unleash the full potential of community pharmacists and thus appears more likely to accelerate the paradigm shift from dispensing and indirect clinical focus to more direct clinical and patient centered healthcare relationships with patients/customers as well as other healthcare professionals.

Other major paradigm shift in community pharmacy services would be attributable to telepharmacy and home delivery of services. The idea of pharmacists being able to render essential public health contributions via telepharmacy and home delivery is built on irrefutable logic. When hospitals are buckled beneath the weight of COVID-19 cases and the world is striving to adhere to the self-isolation and social-distancing rules, telepharmacy and home delivery of medicines are of great significance not only for COVID-19 confirmed or suspected patient, but also for the patients with communicable and non-communicable diseases, and most vulnerable members of the community (i.e, elderly, pregnant women and children). The benefits of these services are represented by a wide range of the pharmaceutical service, including drug review and monitoring, sterile and non-sterile compounding verification, medication therapy management (MTM), patient assessment, clinical consultation, outcomes assessment, decision support, and drug information from medication selection.10 , 11 In the past, these services has been utilized by communities throughout the US, Spain, Denmark, Egypt, France, Canada, Italy, Scotland, and Germany to improve access to pharmacy services, especially in underserved populations.12 Likewise, many countries, such as Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom have now adopted these services in response to COVID-19 pandemic. However, despite dire need of telepharmacy and home delivery of medicines in COVID-19 prevalent developing nations, many factors, such as community pharmacist willingness, limited workforce, lack of expertise, financial reimbursement, infrastructure of community pharmacies may be to blame for low uptake of these services. Regardless of all the barricades, the shift in the community pharmacy paradigm - in terms of identity and recognition as a competent and trustworthy healthcare professionals - is expected to happen through telepharmacy and home delivery of services and medicines due to increased chances for direct interaction with patients in need of these services, only if community pharmacists aim to avail the opportunities rather than moaning about existing issues. They ought to embrace the notion “more the interaction you make, more opportunity you have to make positive impact on others (patients)”

In light of COVID-19 driven medication disruptions and limited access to essential medicines, a number of flexibilities in pharmaceutical regulations have been observed in many nations, which are anticipated to foster the role of community pharmacists.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Pharmacists have been authorized to conduct therapeutic interchange and substitution without physician authorization when product shortages arise to ensure continuity of therapy during shortage of the prescribed medicine. In some countries or territories, pharmacists have been authorized to repeat dispensing of prescribed medicines for patients with long-term conditions in-order to improve patient adherence to medicine therapy and minimize the need for medical appointments. In the same manner, the FDA has temporary authorized compounding pharmacies to compound FDA-approved drugs to address the shortage of certain crucial drugs (i.e., sedatives, anesthetics, painkillers, and muscle relaxants etc) used in the treatment of COVID-19.8 Furthermore, considering the needs of patients requiring controlled drugs, - including opioid medicines for palliative care, severe pain management, or taking regular opioid substitution therapy -, pharmacists are temporarily permitted to extend prescriptions, pass prescriptions to other pharmacists, and allow pharmacy employees to deliver prescriptions of controlled substances to patients' homes. Though these flexibilities in legislations are temporary due to a number of medication safety concerns and irrational practices, at least pharmacists now have the opportunity to take complete accountability for a patient's medication. Pharmacy related organization in other nations must urge these legislations to support patients and prescribers during the COVID-19 response, and enable satisfactory integration of the prescription and supply of medicines. However in developing nations, ensuring the availability of trained pharmacist at community settings and required equipments will be critical components of any initiative to leeway the pharmaceutical legislations.

To sum up, the health governments across the globe are loosening pharmaceutical legislations and expanding community pharmacy services in response to COVID-19 havoc with the clear objective of improving access to requisite healthcare services and medicines. However this may not be easy to follow for developing nations, as community pharmacy services in these settings are thwarted by societal, technical and economic barriers. But, as we see it, healthcare regulators in developing nations, where ensuring access to healthcare services and essential medicines has always been a great challenge, will need to utilize and promote community pharmacy services to cater the needs of vulnerable population during the COVID-19 pandemic. In doing so, community pharmacists across the globe will assume new responsibilities, assist patients attain healthy outcomes and provide value previously unrecognized by the healthcare professionals, population and healthcare system. Nevertheless, in this regard, national pharmacy organizations need to play a key role with clearer and more direct approaches to articulate their suggestions in-order to shift community pharmacy practice from the bleeding edge to the cutting edge. They should ferret out additional indicators of paradigm shifts and request to be included at the table when previous rules are revised or new healthcare policies are being devised.

Funding

None.

Declaration of competing interest

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Leite H., Hodgkinson I.R., Gruber T. Public Money & Management; 2020. New development:‘Healing at a distance’—telemedicine and COVID-19; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson R.M., Heesterbeek H., Klinkenberg D., Hollingsworth T.D. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395(10228):931–934. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cadogan C.A., Hughes C.M. On the frontline against COVID-19: community pharmacists’ contribution during a public health crisis. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.015. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng S., Yang L., Zhou P., Li H., Liu F., Zhao R. Recommendations and guidance for providing pharmaceutical care services during COVID-19 pandemic: a China perspective. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.012. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Australia P.S.o. 2020. Summary of COVID-19 Regulatory Changes.https://www.psa.org.au/coronavirus/regulatory-changes/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen L., Alice T., Smart Biggar. Jdsupra; 2020. From Regulatory Flexibility to Reimbursement Changes, How Canadian Regulators and Payers Are Managing the COVID-19 Crisis.https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/from-regulatory-flexibility-to-47882/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 7.General Pharmaceutical Council . 2020. Update on New Legislation Relating to Controlled Drugs during the COVID-19 Pandemic.https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/news/update-new-legislation-relating-controlled-drugs-during-covid-19-pandemic Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 8.DuBiner Royce, Kate W. Hardey, Brian King, Julie Letwat, Loveland T. Jdsupra; 2020. Pharmacy Developments Related to COVID-19 Testing and Compounding of Critical Drugs.https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/pharmacy-developments-related-to-covid-37270/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 9.Consultant Pharmacist Forum Executive Summary: Pharmacists as Front-Line Responders for COVID-19 Patient Care 2020. https://www.pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/files/APHA%20Meeting%20Update/PHARMACISTS_COVID19-Final-3-20-20.pdf Available from:

- 10.Strand K., Shoulders B.R., Smithburger P.L., Kane-Gill S.L. A systematic review of ICU and non-ICU clinical Pharmacy services using telepharmacy. Ann Pharmacother. 2018;52(12):1250–1258. doi: 10.1177/1060028018787213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander E., Butler C.D., Darr A. ASHP statement on telepharmacy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74(9):e236–e241. doi: 10.2146/ajhp170039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldoni S., Amenta F., Ricci G. Telepharmacy services: present status and future perspectives: a review. Medicina. 2019;55(7):327. doi: 10.3390/medicina55070327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]