Abstract

This study assesses the level of financial vulnerability of Indonesian households using data from the Household’s Balance Sheet Survey (Survei Neraca Rumah Tangga/SNRT) 2016 and 2017. The SNRT are micro-unit of household data that contains information on preferences and behavior. Through both objective and subjective measurements of the Household Financial Vulnerability Index (FVI), we find that the financial vulnerability of Indonesian households is not only strongly influenced by income factors, but also by finance-related behavioral characteristics and several socio-economic factors. As a consistency and robustness check, we also estimate econometric models using the Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS) panel data for the periods 1993, 1997, 2000, 2007 and 2014. Our study then conclude that the level of household financial vulnerability decreased in 2017. Moreover, the study suggests that we should carefully monitor the behaviour of middle income group as they contribute significantly to the household financial vulnerability in Indonesia.

Keywords: Household finance, Financial Vulnerability Index, Measurement, Determinants, Indonesia

1. Introduction

The crisis in 2008, which was caused by securitization of property loans (Cynamon and Fazzari, 2008; Acharya et al., 2009; Kotz, 2009; Mian and Sufi, 2011), provided a valuable message regarding the importance of monitoring the vulnerability of the household sector. The explosion of the crisis was preceded by an increasing trend in the banking sector’s Non-Performing Loans (NPL) to gross total debt and the debt to income ratio of the household sector in the U.S., both indicating that the financial sector was moving toward a crisis. Learning a lesson from the crisis, central banks began paying more attention to the financial vulnerability of households.

Amid the global financial uncertainty, authorities’ concerns were that the financial vulnerability faced by households will proportionately increase in the long run, if effective policy frameworks are not in place. The October 2017 Global Financial Stability Review (GSFR) shows an increase in the household debt to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ratio from 15% to 21% for developing countries, and 52%–63% for developed countries from 2008 to 2016. For Indonesia, in particular, the highest increase in the household debt ratio (i.e. from 9.92% to 10.04%) from 2011 to 20161 . With regard to the growth of the debt ratio, the household sector recorded an average NPL growth of 1.50% per year, with the largest average NPL value being Housing Ownership Loans (KPR) amounting to 2.23% per year, followed by NPLs on Vehicles Motorship Loans (KKB) of 1.33% per year, multipurpose loans of 0.90% per year, household equipment loans of 1.47% per year, and other household loans of 1.43% per year. The largest increase in the NPL was in household equipment loans, growing by 10.6% per year, as well as KPR and KKB, which rose, respectively, to 7.29% and 6.47% per year2 . This situation gives the same signal, as in the U.S, that the household sector in Indonesia tends to be more consumptive in fulfilling living needs, but it is not balanced with adequate financial capacity.

Many studies such as Dartanto and Shigeru (2016), Mian and Sufi (2011), Leika and Marchettini (2017), and Mian et al. (2017) confirm strong interrelationship between household financial vulnerability and financial system stability. Therefore, the Financial Stability Review (FSR) of Bank Indonesia provides statistics on the risk of financial vulnerability in the household sector, which is used as part of the assessment of the resilience of national financial system stability and to measure the impact of a shock in the economic system on households. However, there is still an urgent need to provide FSR of Bank Indonesia many rigorous researches and evidence for policy making process. Given how important issues of household financial vulnerability on macro-financial stability, empirical studies either in Indonesia and other developing countries are remained a peripheral topic, relatively scarce and there is a little variation in data and methodologies between these studies. Abubakar et al. (2018), based on a balance sheet, financial margin, and coping strategies approach, introduces a measurement of household financial vulnerability that use both objective and subjective indicators in emerging countries including Indonesia, thus conclude that the household sector is relatively highly interconnected with the banks.

This lack of research calls for a new initiative to comprehensively and rigorously asses the household financial vulnerability in Indonesia by using unique dataset of SNRT combined with the panel data of Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS) from 1993 to 2014. Our study extends prior studies by providing a deeper investigation of the risk determinants of financial vulnerability and estimates the level of vulnerability of households through the formulation of household financial vulnerability indices based on objective and subjective indicators. These two indicators are complementary in which objective indicators represents a measurable of individual experiences while subjective indicators are based on individual awareness (Bialowolski and Weziak-Bialowolska, 2013). Drawing on the methods applied in the literature, we firstly describe the component of financial vulnerability that may be compiled from the microdata, meaning that we look at household vulnerability from the perspective of the household itself. In the context of household financial vulnerability, the case of Indonesia is very unique and insightful lesson learned. This is because Indonesia is representing an emerging economy with a very diverse socio-economic condition as well as having a fast growing of middle class group (Dartanto et al., 2019). Moreover, Indonesia also experienced a severe the Asian Financial Crisis in 1998. These characteristics may influence household financial vulnerability differently; consequently, the intervention policy may not one size policy fits for all. As this paper measures household financial vulnerability and examines its determinants in Indonesia, the results are an input for the development of macroprudential policies, which are in order to maintain financial system stability in the country. This is timely, given the increasing household financial vulnerability that threatens the financial sector via amplification of risks in Indonesia and worldwide especially in the current condition of COVID-19. Although socio-economic characteristics are different among countries, this study is critical for providing useful insights into the policy makers and stakeholders worldwide that are concerning and mitigating household financial vulnerability and macro-financial stability.

We focus on the household survey namely SNRT3 . We use the SNRT in 2016 and 2017 due to improvement in survey quality. The SNRT 2016 is conducted in 14 provinces in Indonesia with total respondents amounting to 3500 households, while the SNRT 2017 is conducted in 15 provinces4 in Indonesia with 4000 households as respondents. The survey is conducted through direct interviews (face-to-face) based on a multistage random sampling method.

To provide a complete description of the economic characteristics of the respondents, the SNRT respondents are divided into three groups based on income, i.e., 40% belonging to the low income, 40% to the middle income, and 20% to high income groups. For in-depth analysis, this study highlights households from the middle-income group, given the high exposure of households from this group to the financial sector. Besides income factor, we find that behavioral characteristics and socio-economic factors also turned out to be a strong factor to affect the financial vulnerability of Indonesian households. Further, we compare this result with a long run estimations, which is based on the IFLS panel data for the periods 1993, 1997, 2000, 2007 and 2014, and find that those findings are in line for both short and long term.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 summarizes the literature. Section 3 presents the data and methodology. Section 4 presents the results. Section 5 provides the conclusions and policy recommendations.

2. Literature review

2.1. Household financial vulnerability

There is no universally accepted definition of household financial vulnerability in the literature. Anderloni et al. (2012) argues that financial vulnerability occurs due to unsound/unsustainable borrowing practices, which lead households to contract debt levels that are too high relative to their current and future earnings capacity. Thus, debt is one of the most important components of financial vulnerability. The risk of delinquent debt is generally found in the type of debt associated with home loans and in young households, which previously have a relatively large debt (May et al., 2004). In addition to debt, another indicator is the debt service-to-income ratio that reflects debt affordability. Dey et al. (2008) and Bańbuła et al. (2015) suggest that households that have a debt service-to-income ratio greater than 40% belong to “vulnerable households” because they have excessive amount of debt.

The financial vulnerability may also be driven by factors other than debt, such as: low income and wealth levels; life-style behaviors that may be induced by irresponsibility or short-sightedness, and, in turn, unsustainable expenditure or non-optimal money management; adverse events that may negatively impact their financial situation; and/or absence of financial instruments (e.g. life or accident insurance policies) that enable households to manage risk more effectively. This means that a comprehensive household financial vulnerability function will contain financial, demographic, and socio-economic characteristics of households.

A number of studies investigate the sources of household financial vulnerability, and produce interesting findings. Table 1 summarizes these studies. For example, Cox et al. (2002) find that the accumulation of debt and assets of households caused the rapid growth of the household debt and assets in the UK during 1995–2000. They show that household debts tend to be exposed to corrections in house prices, income shocks, and increases in interest rates because the assets tend to be illiquid. Sachin et al. (2018) observe that most households in India borrow from self-help groups (24%), microfinance institutions (12%), and banks (12%), and that part of the loans are used to finance religious ceremonies/festivals (14%) and farming (14%). They show that households in rural areas without land ownership are more vulnerable to financial shocks because such households spend on celebrations/traditions.

Table 1.

Summary of studies on household financial vulnerability.

| Author | Findings |

|---|---|

| Cox et al. (2002) |

|

| Lin and Martin (2007) |

|

| Girouard et al. (2006) |

|

| Nucu (2012) |

|

| Albacete and Peter (2013) |

|

| Bialowolski and Weziak-Bialowolska (2013) |

|

| Bańbuła et al. (2015) |

|

| Bańkowskam et al. (2017) |

|

| Leika and Marchettini (2017) |

|

| Sachin et al. (2018) |

|

To sum up, in addition to using approaches and dimensions related to financial aspects, household finances can also be defined using approaches and dimensions of non-financial aspects e.g. demographic and social characteristics. The main limitation of these studies is that they do not undertake a comparison between short and long-term household financial vulnerability. We fill this research gap by carrying out both cross-sectional and panel data analysis of household financial vulnerability. This provides a compressive picture of the household financial vulnerability phenomenon.

2.2. Relationship between financial vulnerability and macroeconomic stability

The relationship between household financial vulnerability and macroeconomic stability is a two-way relationship. At the macro level, stability, as reflected in the movements in the growth rate of GDP, the inflation rate, and the unemployment rate, greatly affects economic conditions at the micro level. Conversely, developments at the micro level, as reflected in changes in the value of household sector debts and the level of exposure to financial markets, influence conditions at the macro level. To illustrate this, at the micro level, shocks to GDP, for instance, disrupts the sources of household income, which decrease the ability of households to pay their debts. This condition gradually increases the probability of default, causing foreclosure of the collateral for debts such as houses, cars, and other assets. If the number of affected households is large in a region, a high risk of default exposes lenders (typically banks) to bankruptcy. In this sequence, vulnerability at the micro level in turn creates vulnerability at the macro level.

Several empirical studies confirm the significant relationship between household sector financial vulnerability, measured in terms of debt, and financial system stability. Dartanto and Shigeru (2016) show that financial vulnerability in the household sector in the Asian region in 1997 is triggered by the Asian Financial Crisis. Mian and Sufi (2011) argue that the levels of household sector debt and asset prices play an important role in explaining macroeconomic fluctuations. Furthermore, Leika and Marchettini (2017) measure the rate of change in household debt and show that whether or not the relatively high presence of household sector debt disrupts financial system stability depends on the characteristics and institutional settings in each country. Mian, Sufi, and Verner (2017) find that an increase in the household sector debt to GDP ratio leads to a decline in economic growth and an increase in unemployment in the medium term. They show that the purchasing power factor (proxied by the level of income) can also indirectly explain the relationship between household debt and financial system stability. Abubakar et al. (2017) show that the most vulnerable households to default risks are the lower-middle class because these households have a relatively high debt-to-income and debt service-to-income ratio.

3. Data and methodology

3.1. Data

We use the SNRT 2016 and 2017 to analyze the household financial vulnerability thus affect the financial stability system in Indonesia as well. The SNRT is a longitudinal panel survey that produce micro unit of household data. These data contains information on preferences and behavior of households, in terms of consumption, investment, and financial management, especially when facing financial disruptions due to internal and external factors. The SNRT 2016 and 2017 data are selected because the information content is relatively more complete and supports the dimensions of the household FVI. The SNRT sample framework is designed to describe the national economic and financial conditions and represents 77% of the households in Indonesia, which is equivalent to 3500 and 4000 household units for SNRT 2016 and 2017, respectively.

Table 2 shows that the SNRT respondents are dominated by middle and high-income class (KE2 & KE3). Therefore, this shows that the SNRT is the most appropriate microdata for vulnerability research, because the higher and middle-income classes tend to have more debt and, hence, the higher probability of default than the low-income class (Girouard et al., 2006; Handayani et al., 2016). Moreover, the debt ownership of households implies that the low-income class increased by 1.6% in 2017 relative to the previous year, resulting in declining arrears by 60 basis points. Nevertheless, the high and middle-income has relatively more arrears than the lower-income class (see Appendix 1).

Table 2.

Grouping of SNRT Household Economic Classes. This table reports the income classes of households based on expenditure average per month in Indonesian rupiah (IDR). KE1 refers to household with average expenditure below IDR 2.2 million; and hence households in KE1 are in the low-income class. KE2 and KE3 denote, respectively, middle and high-income classes. These groups are arranged by Statistics Department of Bank Indonesia. The changed in expenditure value are based on 2016–2017 SNRT Implementation Guidebook, Bank Indonesia.

| Economic Income Class | Definition of Economic Level Based on Household Expenditures | Expenditure Average household per month (IDR. Million) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Year 2016 | Year 2017 | ||

| Low (KE1) | The lowest 40% expenditure | <2.1 | <2.2 |

| Middle (KE2) | The second lowest 40% expenditure | 2.1–4.7 | 2.2–5 |

| High (KE3) | The highest 20% expenditure | >4.7 | >5 |

The resistance of the Indonesia households to financial shocks can be categorized as low, since only less than 10% of the households saved money that meets their basic life requirements for more than 12 months, while 40%–80% of the households only have savings that meet their needs for less than a month. The high and middle-income classes undertake more social activities than the low-income class, indicating that every income class has different social needs.

3.2. Methodology

In this section, we explore the construction of the FVI as a barometer to evaluate the level of household financial vulnerability at the micro level. We designed FVIs whose values are expressed on an interval scale of 1–10, where the value of 1 indicates that the household is at the minimum level of vulnerability (least vulnerable) and the value 10 indicates that the household is at the maximum vulnerability (most vulnerable).

In order to develop the FVI, we begin by defining household financial vulnerability. Following Anderloni et al. (2012), we jointly analyze the different features of household financial distress, which reflects the overall vulnerability of a household, which comes from the overlap of different components.

Our definition of household financial vulnerability is based on two approaches, adapted from Bialowolski and Weziak-Bialowolska (2013). Firstly, the objective approach predicts the level of financial vulnerability by evaluating the household’s financial condition based on one or more variables whose value can be measured definitively in monetary terms, such as the amount of savings, total expenditure, asset value, and others. Secondly, the subjective approach predicts the level of financial vulnerability by assessing the household’s financial condition based solely on the household’s expectations, feelings or perceptions, including perceptions about difficulties in meeting life’s needs or paying off debt.

The objective approach to measuring the level of household financial vulnerability (also called objective FVI) considers five main aspects, namely (1 debt ownership of households, (2) ownership of arrears, (3) household’s budgeting ability, (4) resistance to financial shocks, and (5) the issuance of basic social activities (see Appendix 2). Managing all these aspects of financial vulnerability can represent a problem from a statistical point of view. As such, we use dimensionality reduction process to check for a reduced number of appropriate combinations of the original variables that summarize household vulnerability from dimensions.

Following Anderloni et al. (2012), we reduce the dimension of the variables using a generalization of the traditional Principal Components Analysis (PCA), the Nonlinear PCA (NLPCA) methodology. This methodology leads to an optimal synthesis of observed variables in a reduced space preserving measurement levels of qualitative ordinal data without assuming a priori differences between their categories. Given the nature of our data and the purpose of constructing the objective and subjective FVIs, we use the Categorical PCA (CATPCA) method. The CATPCA method is an analytical method that identifies variables that have the highest statistical correlation with a phenomenon by forming new data sets with fewer variables than the initial data set, without losing significant information. The value of the correlation generated from the variable identification process is then used as the weight scoring value that can be interpreted as the degree of importance of a variable in explaining a condition, e.g., level of financial vulnerability. The CATPCA method is used to quantify or assign scores for each response choice on the index constituent variables.

To test whether the CATPCA method can provide consistent estimates of the FVI, we calculate the weight score values for each year of the SNRT implementation (i.e., 2016 and 2017). For the objective approach, it can be seen that the order of the degree of importance of the index constituents does not change (see Table 3 ). This shows that the five aspects of the objective approach are stable enough to continue to be used in calculating the FVI. For the subjective approach, it can be seen that the order of the degree of importance of the index constituents changes slightly. In 2017, the household assessed the perception of the ability to anticipate the loss of primary income to be more important than the perception of difficulty in paying the debt. This change is considered reasonable, given the subjectivity of households tends to change according to conditions over time (e.g., fewer households have debt). These findings are quite similar with those of Bialowolski and Weziak-Bialowolska (2013), who find that the interrelations between the financial indicators of Italian households did not change during four measurement occasions (2004–2010).

Table 3.

FVI Compiler Variable Score. This table report the compiler variable score from 0 to 1 to show the correlation of variable explains the financial vulnerable from SNRT-BI 2016 and 2017. Higher score reflects better or important those variables explains the dependent. DEBT is total debt’s own; ARREARS is total arears in one month, BUDGETING SKILLS is ratio expenditure to total income, FINANCIAL RESILIENCE is total deposits or saving owned by household, and SOCIAL EXCLUSION is total expenditure for social activities. MEETING ENDS is perception of household to inability meet basic needs. DEBT SOLVENCY; inability to pay debt. PERCEPTION OF INCOME SHOCK: perception of household’s saving to meet basic needs. PERCEPTION OF EXPENDITURE; the ability of household to finance the unexpected expenditure. PERCEPTION OF CHANGE INCOME CONDITIONS RELATIVE OF LAST YEAR: perception the income level of household relative to last year.

| Vulnerability Index Compiler Variables | SNRT 2016 | SNRT 2017 |

|---|---|---|

| Objective Approach | ||

| Debt | 0.043 | 0.037 |

| Arrears | 0.148 | 0.131 |

| Budgeting Skills | 0.655 | 0.661 |

| Financial Resilience | 0.790 | 0.788 |

| Social Exclusion | 0.538 | 0.550 |

| Subjective Approach | ||

| Meeting Ends | 0.795 | 0.763 |

| Debt Solvency | 0.706 | 0.673 |

| Perception of Income shock | 0.675 | 0.724 |

| Perception of Expenditure shockl | 0.626 | 0.671 |

| Perception of change income conditions Relative of last year | – | 0.448 |

After obtaining the weight score and response choice score of each variable for the two approaches, the next step is to calculate the values of the FVIs —i.e., objective and subjective FVIs—based on the accumulated score for each household with the formula:

| (1) |

where is the value of the score for the variable p, is the value of the response score for the variable p chosen by the household i. The number of households observed in the 2016 and 2017 SNRT’s is 3500 and 4000 units, respectively (see Appendix 3).

In this paper, we use a Fractional Logit regression to analyze the determinants of household financial vulnerability, where objective and subjective FVIs are the dependent variables. Fractional Logit estimation technique is chosen as an alternative to the Ordinary Least Square (OLS) method, given that, theoretically, the OLS method uses the assumption of data distribution from -∞ to +∞, whereas our FVI data is designed to be distributed between the intervals of 1 to 10. When using the OLS method for the FVI analysis, parameter estimates are biased. That is, there is a possibility of a combination of the values of certain independent variables that will produce the estimated FVIs whose values are outside the prescribed interval. We include three groups of independent variables in both regression models, which are: (i) household financial conditions—consists of variables that provide quantitative information, such as, the amount of income, ownership of assets, and total debt held; (ii) household financial behavior—a set of variables that inform household behavior choices in addressing financial difficulties, such as selling items, borrowing money, and delinquent bills; and (iii) socio-regional factors—consists of several variables that provide information about the social and regional characteristics of a household. These categories were created in order to classify whether the household’s vulnerability was triggered by financial condition, household’s coping strategies5 , and/or social factor, thus allowing us to have a better formulation of policy recommendation.

Furthermore, the Fractional Logit estimation technique is applicable if the values of the dependent variable lie within the interval of 0 to 1. Our study defines vulnerability within the interval of 0 to 1. That is, the financial status of the household is translated into a system of proportional numbers, by converting the FVI (which lies within 1 to 10) into a scale of 0.1 to 1.0. According to Abubakar et al. (2018), a household which that has have coping strategies in response to an event occurring, generally have has relatively moderate vulnerabilities level. Further, the link between coping strategies and household vulnerability levels can be seen more comprehensively on heat-map adapted from the Food Security and Early Warning Vulnerability USAID (1999) Assessment Manual.

To facilitate the interpretation of the FVI, rescaling is established so that the FVI values are in intervals of 1–10; this is the FVI adjusted. The formula used for the rescaling is expressed by the following equation:

| (2) |

where the Upper Bound and Lower Bound denote, the maximum and the minimum bounds of the FVI, respectively. FVI max and FVI min are, respectively, the maximum and the minimum values of the FVI of rescaling, i.e., 10 and 1. This method allows us to analyze the FVI and its determinants using the Fractional Logit approach. The Fractional Logit regression model can be written as follows:

| (3) |

where is log-likelihood of household vulnerability, and x is a vector of independent variables (i.e. the determinants of household vulnerability). The log-likelihood cannot be interpreted directly, intuitively. Hence, a commonly used statistic in the literature is the marginal effect of the Fractional Logit estimation. The marginal effect is obtained as follows:

| (4) |

The interpretation of the marginal effect from the Fractional Logit model is similar to the OLS case. In the case of the Fractional Logit, the value of x is very relevant to the magnitude of the marginal effect. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the value x, which will be the basis for calculating the marginal effect. The marginal effect is calculated using the average value of x (i.e. at means). Another difference is that by first transforming the variable —i.e. by scaling by a factor of 10—the actual marginal effect of FVI needs to be multiplied by a factor of 10 to intuitively interpret the estimated coefficients as the impact of changes in the independent variable on FVI.

Given that the SNRT data is available for only two periods, we separate the regressions into two: (1) cross-sectional regression analysis (SNRT 2017); and (2) panel data regression analysis (SNRT 2016 and 2017). The cross-sectional regression analysis is based on the Fractional Logit approach in (3), (4). For the panel data regression analysis, we use the random-effects estimator. We select the random-effects estimator because the data only consist of 2 years period that assumed it has small values to change between variables (Allison, 2005). In contrast to the cross-sectional analysis, the dependent variable used to measure household vulnerability in panel data regression analysis is financial margin, whose values lie within the interval -∞ to + ∞. Hence, the marginal effects are the direct coefficients of the model.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive

4.1.1. Analysis of the financial vulnerability index

In Table 4 , the average levels of Indonesian household financial vulnerability for 2016 based on a scale of 1–10 are 6.03 and 6.40, respectively, for objective and subjective FVIs. The results show that, in 2017, the level of household financial vulnerability reduced relative to 2016, based on the two indices. That is, the average levels of household financial vulnerability fell to 5.06 and 5.5 for objective and subjective FVIs, respectively. The difference in value between the two FVIs indices indicates how accurately the household conducts a self-assessment of its financial condition. If the value of the objective FVI is relatively higher than the subjective FVI, then the households can be interpreted as having overconfidence in their financial vulnerability condition and tend to prioritize consumption over investment. In contrast, a relatively lower objective FVI to subjective FVI indicates that households lack confidence in their financial vulnerability condition, are extra careful about spending, and tend to prioritize investment over consumption. The ideal condition is reached when the household’s objective FVI equals its subjective FVI.

Table 4.

Adjusted FVI Rescaling Results. This table report rescaling value of the accumulative score of objective (Debt, Arrears, Budgeting Skills, Financial Resilience, and Social Exclusion) and Subjective (Meeting Ends, Debt Solvency, Perception of Income Shock, Perception of Expenditure Shock and Perception of Change Income Condition relative to Last Year). For Each FVI, we report, total observation, average, standard deviation and the score that has been rescaling from 1 to 10.

| Index | Obs. | Average | Std.Dev. | Min Score | Max Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FVI Objectives – 2016 | 3.500 | 6.033 | 2.271 | 1 | 10 |

| FVI Objectives – 2017 | 3.500 | 5.662 | 2.315 | 1 | 10 |

| FVI Subjectives – 2016 | 4.000 | 6.452 | 1.755 | 1 | 10 |

| FVI Subjectives – 2017 | 4.000 | 5.567 | 2.230 | 1 | 10 |

Although the level of household financial vulnerability in 2017 improved relative to the previous year, some households feel that their financial conditions are relatively worse than their actual conditions. This can be seen from the linear correlation of financial vulnerability between the two indices, classified by the household economic class. Fig. 1 shows these correlations. The R-squared values in panel (a) to (f) are, respectively, 29%, 31%, 20%, 46%, 49%, and 38%. Compared to the two other economic classes (low and high classes), the average measure of the objective financial vulnerability best in explains variations in subjective financial vulnerability in the middle economic class.

Fig. 1.

Correlation between FVI objective - subjective (mean) per economy class.

Three interesting points can be drawn from the correlation between the two household FVIs: (1) Both are very useful when analyzing the household financial vulnerability; (2) households that have vulnerable characteristics based on the subjective FVI do not necessarily have vulnerable characteristics based on the objective FVI, because asymmetric information can bias efforts to mitigate the risk of household financial vulnerability; and (3) variations in the triggers of subjective financial vulnerability of the upper economic class (KE3) are relatively more unpredictable compared to other economic classes.

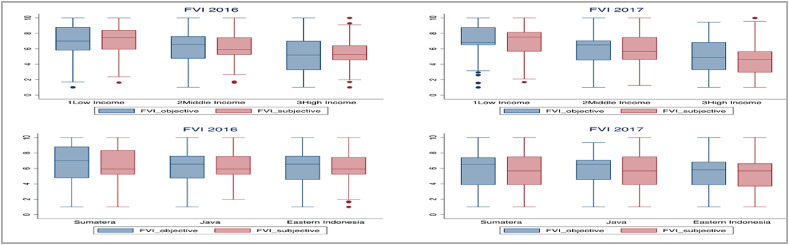

Furthermore, the two FVIs consistently show that the level of financial vulnerability varies across household economic classes (see Fig. 2 ). The higher the level of expenditure as the household moves into the upper economic class, the lower the average value of both objective and subjective FVIs. In the low-income class, the average value of subjective FVI is relatively higher than the average value of objective FVI, thus reflecting that this household group feels relatively more vulnerable than the actual conditions. In contrast, the middle-income class has an average value of subjective FVI relatively lower than the average value of objective FVI, which reflects an attitude of overconfidence in the stability of financial conditions. As a result, this household group is assumed to have a preference towards consumption level that is relatively higher than the investment level. For the high-income class, the average subjective FVI value is relatively the same as the average value of the objective FVI. Accordingly, this household group is able to accurately conduct self-assessments regarding the level of financial vulnerability.

Fig. 2.

Box-plot analysis between objective FVI and subjective FVI.

4.2. Determinants of financial vulnerability

Table 5 and Table 6 present the household financial vulnerability regression estimates for cross-sectional and panel data, respectively. We report the marginal effects and standard errors for both data types (cross-sectional and panel) and FVIs (objective and subjective). We include, in the regressions, the two independent variables commonly used in the financial vulnerability literature, i.e., debt-to-income ratio and consumption of credit-to-total credit ratio. Prior work shows that debt to income ratio and ratio of consumer credit to total credit are positively correlated with household vulnerability (Dey et al., 2008), which we find to hold true. Other variables, such as income (Handayani et al., 2016) and asset ownership, such as jewelry, land, and bank savings can decrease household vulnerability (Djoudad, 2012; Bialowolski and Weziak-Bialowolska, 2013), which we find to hold true. In addition, we report results for coping strategies chosen by households.

Table 5.

Financial Vulnerability Estimation Determinants (Cross-Section). This table shows determinants estimation of financial vulnerabilities using SNRT 2017 using 29 determinants which is divide to subjective measures and objective measure. To note, M.E.: Marginal Effect, S.E: Standard Error and Significance level ∗∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗p < 0.05, ∗p < 0.1.

| Dependent Variable: Financial Vulnerability Index |

Subjective Measures |

Objective Measures |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M.E. | S.E | M.E. | S.E | |

| Debt to Income Ratio | 0.001 | (0.001) | 0.000∗∗ | (0.001) |

| Consumption Credit to Total Credit Ratio | 0.004∗∗∗ | (0.001) | 0.004∗∗∗ | (0.001) |

| Household Income (Log) | −0.790∗∗∗ | (0.047) | −1.180∗∗∗ | (0.047) |

| Land Price (Log) | 0.030 | (0.019) | −0.020 | (0.020) |

| Bank Savings Dummy | −0.570∗∗∗ | (0.089) | −0.770∗∗∗ | (0.080) |

| Home/Land ownership Dummy | −0.530∗∗∗ | (0.122) | −0.130 | (0.114) |

| Home Ownership Dummy | −0.830∗∗∗ | (0.079) | −0.440∗∗∗ | (0.075) |

| Age of Head of Household | −0.010∗∗∗ | (0.003) | 0.004 | (0.003) |

| Household Size (household budget) | 0.094∗∗∗ | (0.020) | 0.157∗∗∗ | (0.020) |

| Financial Assistance Recipient | 0.180∗∗∗ | (0.068) | 0.215∗∗∗ | (0.068) |

| Overseas Remittance Recipient | −0.100 | (0.207) | 0.190 | (0.235) |

| Average savings account per household | −0.460∗∗∗ | (0.118) | −0.450∗∗∗ | (0.079) |

| Dummy Variable for Coping Strategies (base: savings withdrawal) | ||||

| Minimizing Expenditure | 0.626∗∗∗ | (0.084) | 0.360∗∗∗ | (0.085) |

| Selling goods | 0.398∗∗∗ | (0.107) | 0.301∗∗∗ | (0.109) |

| Work longer | 0.892∗∗∗ | (0.149) | 0.182 | (0.153) |

| Extra work | 0.568∗∗∗ | (0.133) | 0.394∗∗∗ | (0.132) |

| Borrow food from neighbor/friend | 1.306∗∗∗ | (0.104) | 0.464∗∗∗ | (0.100) |

| Borrow from employer | 0.995∗∗∗ | (0.269) | 0.535∗∗ | (0.235) |

| Pawn of goods | 0.462∗∗ | (0.211) | 0.462∗∗ | (0.217) |

| Borrow from traditional microfinance (Arisan) | 1.383∗∗∗ | (0.347) | 0.938∗∗∗ | (0.300) |

| Home Equity Loan | 1.667∗∗∗ | (0.447) | 0.305 | (0.871) |

| Loan Takeover | 1.793∗∗∗ | (0.261) | −0.370 | (1.214) |

| Credit Card | 0.296 | (0.187) | 0.907∗∗∗ | (0.165) |

| Bank Loans | 0.089 | (0.225) | 0.708∗∗∗ | (0.197) |

| Loan from employers | 1.153∗∗∗ | (0.444) | 0.679∗∗ | (0.291) |

| Informal loan/loan shark | 1.689 | (1.232) | 0.130 | (0.635) |

| Unpaid Claims | 3.317∗∗∗ | (0.467) | 1.125∗ | (0.683) |

| IKNB Loans | −0.480 | (0.951) | −0.020 | (0.768) |

| Others | 1.474∗∗∗ | (0.433) | 0.207 | (0.332) |

| Control Variable: | ||||

| Province Dummy | Yes | Yes | ||

| Area Dummy (City-Village) | Yes | Yes | ||

| Total Observation | 3671 | 3671 | ||

Table 6.

Determinants Estimation of Household Financial Vulnerability (Panel). This table shows determinants estimation of financial vulnerabilities using panel data of SNRT 2016 and 2017. It has 12 determinants, which is divide to subjective measures and objective measure. To note, M.E.: Marginal Effect, S.E: Standard Error and Significance level ∗∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗p < 0.05, ∗p < 0.1.

| Dependent Variables: Financial Vulnerability Index |

Subjective Measures |

Objective Measures |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M.E. | S.E | M.E. | S.E | |

| Debt to Income Ratio | 0.000 | (0.000) | 0.000∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Consumption Credit to Total Credit Ratio | 0.004∗∗∗ | (0.001) | 0.004∗∗∗ | (0.001) |

| Household Income (Log) | −0.690∗∗∗ | (0.035) | −1.130∗∗∗ | (0.038) |

| Land Price (Log) | 0.000 | (0.011) | −0.030∗∗∗ | (0.012) |

| Bank Savings Ownership Dummy | −0.770∗∗∗ | (0.052) | −0.390∗∗∗ | (0.058) |

| Home/Land Ownership Dummy | −0.500∗∗∗ | (0.088) | −0.260∗∗∗ | (0.083) |

| Jewelry Ownership Dummy | −0.700∗∗∗ | (0.053) | −0.500∗∗∗ | (0.054) |

| Age of Head of Household | −0.010∗∗∗ | (0.002) | 0.004∗∗ | (0.002) |

| Household Size (household budget) | 0.093∗∗∗ | (0.016) | 0.108∗∗∗ | (0.023) |

| Financial Assistance Recipient | 0.142∗∗∗ | (0.046) | 0.266∗∗∗ | (0.049) |

| Overseas Remittance Recipient | −0.220 | (0.191) | 0.120 | (0.246) |

| Average savings account per household | −0.650∗∗∗ | (0.110) | −1.000∗∗∗ | (0.120) |

| Control Variables: | ||||

| Coping Strategies Dummy | Yes | Yes | ||

| Province Dummy | Yes | Yes | ||

| Area (Urban-Rural) Dummy | Yes | Yes | ||

| Total Observation | 3671 | 3671 | ||

The estimated coefficients in Table 5 can be interpreted as an additional FVI unit value, on average, due to a unit increase in the independent variable, ceteris paribus. However, there are exceptions to the interpretation of land prices and household income. The parameter estimation of these two variables are based on a linear-logarithmic model. Thus, the value of FVI, on average, will decrease or increase by one unit if income per land price increase by 172%.

Five interesting findings can be drawn from these results. Firstly, asset ownership is consistently associated with a decrease in the level of financial vulnerability. For certain types of assets, ownership is associated with a lower level of vulnerability. For example, at a 99% confidence level, ownership of savings and jewelry is associated with lower objective FVI values relative to ownership of houses and land assets.

Secondly, the level of income is negatively associated with the level of financial vulnerability (see Fig. 3 ), which is consistent with the basic microeconomic theory. In theory, households with higher income are more able to absorb negative shocks (increase in inflation, for instance). This finding contradicts Handayani et al. (2016), who find that increasing income level is associated with a higher level of household debt, and, by extension, higher vulnerability.

Fig. 3.

The correlation among FVI subjective, FVI objectives, and household income.

Thirdly, ownership of building or land assets has no statistically significant effect on the level of financial vulnerability, which contradicts the finding of Sachin et al. (2018). This is quite surprising, given that households who own buildings in relatively expensive areas should have higher purchasing power, and thus should be less financially vulnerable. One possible explanation is that building assets are highly illiquid and are practically difficult to be used by households facing unexpected expenses. Another explanation is that the houses that are located in relatively expensive areas are very likely to have been obtained several decades ago or inherited from previous generations, so that households living in such areas do not immediately have high purchasing power.

Table 7 presents the cross-sectional estimates of the marginal effects of economic classes. In general, the factors that influence household vulnerability in this table are consistent with those in Table 5. Nevertheless, there is a tendency that the household vulnerability in the upper economic classes is more sensitive to the coping strategies/behavioral factors associated with formal financial institutions. The level of vulnerability of the upper economic class households is also more sensitive to changes in income when compared to lower economic class households.

Table 7.

Estimation of Financial Vulnerability Determinants by Economic Class. This table shows determinants estimation of financial vulnerabilities by economic class using SNRT 2017 which is divided into three different measures for Low, Middle and High Income class of household that differ to subjective and objective index. To note, M.E.: Marginal Effect, S.E: Standard Error and Significance level ∗∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗p < 0.05, ∗p < 0.1.

| Dependent Variables: Financial Vulnerability Index |

Low Income Class |

Middle Income Class |

High Income Class |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective |

Objective |

Subjective |

Objective |

Subjective |

Objective |

|||||||

| M.E. | S.E | M.E. | S.E | M.E. | S.E | M.E. | S.E | M.E. | S.E | M.E. | S.E | |

| Debt to Income Ratio | 0.000 | (0.002) | 0.000 | (0.002) | 0.002∗∗ | (0.001) | 0.000 | (0.001) | 0.000 | (0.001) | 0.000 | (0.001) |

| Consumption Credit to Total Credit Ratio | 0.012∗∗∗ | (0.002) | 0.006∗∗∗ | (0.002) | 0.004∗∗∗ | (0.001) | 0.004∗∗∗ | (0.001) | 0.003∗∗ | (0.001) | 0.004∗∗∗ | (0.001) |

| Bank Savings Ownership Dummy | −0.740∗∗∗ | (0.260) | −0.640∗∗ | (0.264) | −0.550∗∗∗ | (0.116) | −0.910∗∗∗ | (0.109) | −0.060 | (0.213) | −0.730∗∗∗ | −0.730∗∗∗ |

| Home/Land Ownership Dummy | −0.570∗∗ | (0.236) | −0.470∗∗ | (0.212) | −0.430∗∗ | (0.185) | −0.250 | (0.163) | −0.500∗∗ | (0.203) | 0.176 | (0.222) |

| Jewelry Ownership Dummy | −0.450∗∗∗ | (0.144) | −0.210 | (0.134) | −0.820∗∗∗ | (0.115) | −0.470∗∗∗ | (0.106) | −1.080∗∗∗ | (0.154) | −0.670∗∗∗ | (0.144) |

| Household Income (Log) | −0.180 | (0.117) | −1.100∗∗∗ | (0.141) | −0.620∗∗∗ | (0.092) | −1.940∗∗∗ | (0.114) | −0.730∗∗∗ | (0.076) | −1.350∗∗∗ | (0.082) |

| Land Prices (Log) | 0.047 | (0.040) | 0.019 | (0.039) | 0.052∗ | (0.028) | 0.001 | (0.029) | 0.014 | (0.037) | −0.070∗ | (0.039) |

| Financial Assistance Recipient | 0.263 | (0.166) | 0.026 | (0.158) | 0.319∗∗∗ | (0.098) | 0.222∗∗ | (0.096) | −0.060 | (0.117) | 0.169 | (0.113) |

| Oversea Remittance Recipient | −0.020 | (0.589) | −0.270 | (0.480) | −0.330 | (0.288) | −0.050 | (0.300) | 0.186 | (0.342) | 0.104 | (0.386) |

| Bank Account Average per household members | −0.110 | (0.602) | −0.830 | (0.606) | −0.250∗ | (0.131) | −0.540∗∗∗ | (0.152) | −0.520∗∗∗ | (0.150) | −0.550∗∗∗ | (0.137) |

| Age of Head of the Household | 0.000 | (0.006) | 0.000 | (0.005) | 0.000∗∗ | (0.004) | 0.003 | (0.004) | 0.000 | (0.005) | 0.004 | (0.005) |

| Household Budget | 0.124∗∗ | (0.048) | 0.178∗∗∗ | (0.044) | 0.161∗∗∗ | (0.031) | 0.153∗∗∗ | (0.030) | 0.067∗∗ | (0.029) | 0.094∗∗∗ | (0.030) |

| Province (Urban-Rural) Dummy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Coping Strategies Dummy Variable (on the basis of savings withdrawal) | ||||||||||||

| Minimizing Expenditures | 0.605∗∗ | (0.282) | 0.369 | (0.269) | 0.631∗∗∗ | (0.122) | 0.478∗∗∗ | (0.126) | 0.626∗∗∗ | (0.133) | 0.382∗∗∗ | (0.129) |

| Selling goods | 0.134 | (0.308) | 0.506∗ | (0.270) | 0.390∗∗ | (0.159) | 0.381∗∗ | (0.159) | 0.467∗∗∗ | (0.173) | 0.324∗ | (0.177) |

| Work longer | 0.758∗∗ | (0.334) | 0.560∗ | (0.299) | 0.744∗∗∗ | (0.211) | 0.287 | (0.219) | 0.851∗∗∗ | (0.312) | −0.050 | (0.333) |

| Extra work | 0.307 | (0.312) | 0.396 | (0.335) | 0.402∗∗ | (0.186) | 0.472∗∗∗ | (0.172) | 0.937∗∗∗ | (0.265) | 0.461∗ | (0.263) |

| Borrow Food from friends or neighbors | 1.261∗∗∗ | (0.291) | 0.336 | (0.277) | 1.220∗∗∗ | (0.152) | 0.752∗∗∗ | (0.141) | 1.268∗∗∗ | (0.178) | 0.398∗∗ | (0.174) |

| Borrow from Employer | 1.008∗∗ | (0.467) | 0.274 | (0.385) | 1.056∗∗ | (0.425) | 1.269∗∗∗ | (0.397) | 0.348 | (0.434) | 0.194 | (0.443) |

| Pawn of Goods | 0.558 | (0.740) | −0.240 | (0.498) | 0.206 | (0.292) | 0.616∗ | (0.331) | 0.774∗∗ | (0.325) | 0.513 | (0.326) |

| Borrow from traditional microfinance (arisan) | 1.488∗∗∗ | (0.428) | 1.168∗∗∗ | (0.438) | 1.676∗∗∗ | (0.568) | 1.687∗∗∗ | (0.411) | 0.566 | (0.493) | 0.000 | (0.513) |

| Home Equity Loan | 3.521∗∗∗ | (0.251) | 1.360∗∗∗ | (0.280) | 0.822∗∗ | (0.337) | −1.100∗∗∗ | (0.350) | 1.674∗∗∗ | (0.394) | 0.593 | (1.042) |

| Loan Takeover | 1.838∗∗∗ | (0.457) | −0.970 | (1.218) | ||||||||

| Credit Cards | 0.308 | (0.293) | 0.574∗ | (0.301) | ||||||||

| Bank Loan | 0.002 | (1.479) | 1.971∗∗∗ | (0.388) | 0.281 | (0.404) | 0.963∗∗∗ | (0.351) | 0.180 | (0.267) | 0.287 | (0.264) |

| Loan from Work | −0.070 | (0.471) | 0.723∗∗ | (0.340) | −0.050 | (0.846) | 0.240 | (0.322) | 2.092∗∗∗ | (0.542) | 1.085∗∗∗ | (0.374) |

| Borrow informally/loan sharks | 1.817 | (1.510) | 0.018 | (0.788) | 1.176∗∗∗ | (0.221) | 1.636∗∗∗ | (0.217) | ||||

| Unpaid Claims | 3.520∗∗∗ | (0.251) | −2.030∗∗∗ | (0.480) | 3.287∗∗∗ | (1.002) | −0.020 | (0.369) | 3.580∗∗∗ | (0.280) | 2.818∗∗∗ | (0.294) |

| IKNB Loans | 0.540 | (1.277) | 0.754∗ | (0.392) | −1.690∗∗∗ | (0.557) | −1.290 | (1.662) | ||||

| Others | 1.987∗∗∗ | (0.553) | 0.581 | (0.592) | 1.660∗∗∗ | (0.444) | 0.603 | (0.569) | 0.670 | (0.968) | −0.480 | (0.588) |

| Observation Total | 633 | 633 | 1630 | 1630 | 1408 | 1408 | ||||||

Table 7 also shows that the parameter values for a household for each economic class tend to differ, even though the direction is the same. For instance, an increase income reduces the level of financial vulnerability more in the middle and upper economic class households relative to the low economic class households. Besides, the consumption credit ratio increases the vulnerability of lower economic class households more when compared to the middle and upper economic class households. Some coping strategies are relatively less effective in reducing the level of vulnerability, except for selling goods, looking for loans from the office, pawning goods, and looking for additional jobs, especially for the lower economic class households, given the low access to formal employment/formal financial institutions for this household group.

Table 8 presents the cross-sectional and panel data regression estimates, using financial margin as a measure of vulnerability. The results for coping strategies are not reported for the panel data case, because the SNRT 2016 data does not contain this information. Both regression estimates are consistent with the preceding ones. Note that since the measure of vulnerability using financial margin derived from the SNRT data is different from the one from the IFLS data, we cannot compare these results.

Table 8.

Determination ofHousehold Financial Vulnerability: Financial Margin. This table shows financial margin (financial asset minus debt) as determination of financial vulnerability using SNRT 2017 for cross-section and SNRT 2016 and 2017 for panel data. Coping strategies only shown in cross-section regression due to data availability. To note, M.E: Marginal Effect, S.E: Standard Error and Significance level ∗∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗p < 0.05, ∗p < 0.1.

| Dependent Variables: Financial Margin |

SNRT 2017 |

SNRT 2016–2017 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M.E. | S.E. | M.E. | S.E. | |

| Debt to Income Ratio | −0.003∗∗∗ | (0.000) | −0.002∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Consumption Credit to Total Credit Ratio | −0.002∗∗∗ | (0.000) | −0.002∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Household Income (Log) | 0.589∗∗∗ | (0.023) | 0.562∗∗∗ | (0.017) |

| Land Price (Log) | 0.063∗∗∗ | (0.010) | 0.070∗∗∗ | (0.006) |

| Bank Savings Ownership Dummy | 0.452∗∗∗ | (0.042) | 0.431∗∗∗ | (0.028) |

| Home/Land Ownership Dummy | 2.397∗∗∗ | (0.061) | 2.345∗∗∗ | (0.045) |

| Jewelry Ownership Dummy | 0.306∗∗∗ | (0.038) | 0.304∗∗∗ | (0.028) |

| Age of Head of Household | 0.017∗∗∗ | (0.001) | 0.015∗∗∗ | (0.001) |

| Household Size (household budget) | −0.040∗∗∗ | (0.010) | −0.020∗∗∗ | (0.007) |

| Financial Assistance Recipient | −0.052 | (0.036) | 0.008 | (0.026) |

| Overseas Remittance Recipient | −0.075 | (0.121) | −0.109 | (0.124) |

| Average savings account per household | 0.216∗∗∗ | (0.038) | 0.419∗∗∗ | (0.033) |

| Coping Strategies Dummy Variables (on the basis of savings withdrawal) | ||||

| Minimizing Expenditures | −0.192∗∗∗ | (0.045) | ||

| Selling goods | −0.074 | (0.056) | ||

| Work longer | −0.337∗∗∗ | (0.076) | ||

| Extra work | −0.196∗∗∗ | (0.068) | ||

| Borrow Food from friends or neighbors | −0.232∗∗∗ | (0.052) | ||

| Borrow from Employer | −0.141 | (0.127) | ||

| Pawn of Goods | −0.132 | (0.111) | ||

| Borrow from traditional microfinance (arisan) | −0.093 | (0.166) | ||

| Home Equity Loan | −0.084 | (0.412) | ||

| Loan Takeover | −0.067 | (0.653) | ||

| Credit Cards | 0.123 | (0.919) | ||

| Bank Loan | −0.008 | (0.113) | ||

| Loan from Work | −0.301 | (-0.198) | ||

| Borrow informally/loan sharks | −0.972∗∗ | (0.412) | ||

| Unpaid Claims | −0.742∗∗ | (0.378) | ||

| IKNB Loans | −0.158 | (0.413) | ||

| Others | −0.19 | (0.183) | ||

| Observation Total | 3.624 | 6.450 | ||

4.3. Confirmatory Robustness of Estimates

To test the consistency of the results of the household financial vulnerability determinants based on the SNRT data, which is presented in the preceding section, we conduct a similar estimation using panel data sourced from the IFLS for the periods 1993, 1997, 2000, 2007 and 2014. Since the IFLS does not contain rich information relative to the SNRT data, we are only able to replicate the household financial vulnerability regression model using the concept of financial margin as the dependent variable. The independent variables are household financial conditions, household financial behavior, social, regional, and shock characteristics.

The household financial characteristics relate to assets owned by households, which include, among others, non-business fixed assets (such as, land, houses, household equipment, household furniture, and vehicles), non-business receivables, non-business jewelry, assets in agricultural business, and assets in non-agricultural businesses. The household financial behavior is related to ownership of financial assets by households, such as savings and debt. The social characteristics are the demographic characteristics and occupational information of the household. The regional characteristics are household locations—that is, whether they are located in Java/outside Java and in urban/rural areas. The shock characteristics are events that generate economic shocks to households; for example, sudden illnesses, deaths or crop failures. Table 9 presents the regression results of the household financial vulnerability determinants, as measured by the financial margin approach based on the IFLS data.

Table 9.

Financial Vulnerability Determinants Household: Financial Margin (IFLS). This table show panel regression of financial margin using IFLS data set 1993, 1997, 2000, 2007, and 2014. The determinant is divided by household financial characteristics, financial attitudes (dummy of saving and debt ownership), social characteristic such as gender of head of household, dummy electricity access and etcetera. Regional characteristic (java and rural area) and based on shock characteristics such as decrease of number of household’s member and harvest failure dummy. We report coefficient and Standard deviation (SD) Significance level ∗∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗p < 0.05, ∗p < 0.1.

| Dependent Variables: Financial Margin (Log) | Coefficient | SD |

| Household Financial Characteristics: | ||

| Non-Business Fixed Asset Value Owned by household (million rupiahs) | 0.003∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Non-Business Animals Owned by household (million rupiahs) | 0.009 | (0.162) |

| Non-Business Receivables Owned by household (million rupiah) | 0.004∗∗∗ | (0.004) |

| Non-Business Jewelry Owned by household (million rupiah) | 0.032∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Agricultural Business Asset Value Owned by household (million rupiahs) | 0.001∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Non-Agricultural Business Asset Value Owned by household (million rupiahs) | 0.001∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Household Financial Attitudes: | ||

| Savings Ownership Dummy | 0.437∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Debt Ownership Dummy | −0.241∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Social Characteristics: | ||

| Employee Household Budget | 0.333∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Electricity Access Dummy | 0.878∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Male Household leader Dummy | −0.032 | (0.177) |

| Year of Education of Head of Household | 0.079∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Head of Household Field of Occupation: Agriculture, Mining, and Excavation | 0.617∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Head of Household Field of Entrepreneurship: Manufacturing Industry, Processing, and Construction | 0.770∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Regional Characteristics: | ||

| Java Dummy | −0.151∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Rural Dummy | 0.595∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Shock Characteristics: | ||

| Deceased or Sick Household Members Dummy | −0.339∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Harvest Failure Dummy | −0.317∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Constants | 12.90∗∗∗ | (0.000) |

| Total Observation (household) | 7.900 (2.802) | |

The regression results provide the following findings. Firstly, an increase in the number of assets owned by the households improve the financial margin, which means that the households become relatively less vulnerable if the number of assets increases. This is because large assets can be used as a tool to increase household productivity, which, in turn, enhances household income and, consequently, an insurance in times of financial difficulties. This result is consistent with the one reported for the regression of household financial vulnerability determinants using the FVI measures derived from the SNRT data.

Secondly, ownership of financial instruments has a significant effect on the level of household financial vulnerability. For instance, household savings increases the financial margin. This is because household savings will increase liquidity and reduce the gap between income and expenditure, thereby encouraging consumption smoothing, and, consequently, making the households increasingly financially vulnerable. Conversely, debt ownership reduces the financial margin, because the existence of debt shows that there is payment in the future, which, then, makes households increasingly vulnerable.

Thirdly, for social characteristics, an increase in the supply of household labor increases the financial margin. That is, members of the household work; so, in total, households receive more income than they spent. The educational level predicts household financial margins. That is, households with relatively high levels of education are better able to manage household finances, thereby making such households less vulnerable.

Finally, concerning the characteristics of the shocks, we find that economic disruptions reduce the financial margin, and, then, increase the financial vulnerability of the households. Examples of economic disturbances, in this case, include: (i) sickness or death of a household member, which causes a reduction/loss of part of the income of the household as a whole, thereby reducing the financial margin by 33.9%; and (2) crop failure in agricultural businesses, thereby reducing the financial margin by 31.7%.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we propose FVI, from objective and subjective perspective. To measure vulnerability in the short term, we compiled an FVI using data from the SNRT 2016 and 2017. Then for the long-term vulnerability, we develop an FVI with Financial Margin (FM) using the IFLS data for the periods 1993, 1997, 2000, 2007 and 2014.

The first key finding is that the concept of household financial vulnerability, operationalized with subjective and objective indicators, is two-dimensional. One dimension is associated with the financial position of a household, while the other results from the ability to manage income and financial shocks (prudence versus imprudence). These two dimensions are naturally correlated because households with better financial positions are also in better situations to manage their income.

We find that, in the short term, the level of financial vulnerability of the household sector in Indonesia declined. Specifically, objective vulnerability declined from 6.0 to 5.6, while subjective vulnerability declines from 6.4 to 5.5. Aside, we find that: (i) financial vulnerability is strongly influenced by income factors, finance-related behavioral characteristics, and several socio-economic factors; and (ii) ownership of assets (both financial and real assets), effectively reduced the level of household vulnerability. This finding is in line with the long-term vulnerability estimates.

These findings have several policy implications. Firstly, policies that combine inclusion and financial literacy are needed, including efforts to increase savings in the household sector to maintain the level of financial vulnerability of this sector, particularly within the middle-income class. Secondly, although, in general, the initial results do not indicate a strong relationship between the size of household debt and vulnerability, there are signs that households with a higher portion of consumption loans tend to be slightly more vulnerable. The middle-income class is increasingly gaining access to the financial system, and is increasingly funding its vehicular and housing needs through credit. This means that more attention needs to be given to the consequences of the increasing credit access on long-term macroprudential policies.

Declaration of competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

The authors thanks to the Head of Macroprudential Policy Department, Bank Indonesia, and Yusuf Sofiyandi, Alvin Ulido, Faizal Moeis, Nia Kurnia, Ratih Kumala Dewi (LPEM Universitas Indonesia) and M. Fitri Hidayatullah (Research Fellow) for their assistance. We also gratefully thank to two anonymous referees for valuable and insightful comments for improving our article. The conclusions, opinions, and views expressed by authors in this paper are the authors’ conclusions, opinions, and views and are not conclusions, opinions, and views of Bank Indonesia.

Commercial Bank Statement, 2016 and Central Bureau of Statistic, data processsed

Commercial Bank Statement, 2016

The SNRT aims to: (i) obtain information on the structure of Indonesia’s household balance sheet, (ii) build the data to design a surveillance framework, and (iii) obtain asset and liability data of the household sector in composing National and Regional Balance Sheets and financial imbalance indicators.

The provinces in the discussion were North Sumatera, West Sumatera, South Sumatera, Jakarta Special Region, West Java, Central Java, East Java, Bali, West Kalimantan, South Kalimantan, East Kalimantan, North Sulawesi, South Sulawesi, and Maluku in SNRT 2016 and additional Province Riau in SNRT 2017.

According to Abubakar et al. (2018), a household that has coping strategies in response to an event occurring, generally has a relatively moderate vulnerabilities level. Further, the link between coping strategies and household vulnerability levels can be seen more comprehensively on heat-map adapted from the Food Security and Early Warning Vulnerability USAID (1999) Assessment Manual.

Appendix 1.

Descriptive Statistics of SNRT 2016 and 2017.

The sample distribution by economic class of households (left) and Level education of family head (right).

Household’s Debt Ownership (left) and Ownership of Arrears (right).

The Issuance of Basic Social Activities (left) and Resistance to Financial Shocks (right).

Appendix 2.

FVI Compiler Indicator

FVI Compiler Indicator Based on the Objective Approach.

| Indicator | Inquiries | Response |

|---|---|---|

| Debt | Does household need debt, whether it is paid in installments regularly or irregularly, to finance business needs or daily necessities including education and health? | Yes/No |

| Arrears | Has household ever been in arrears in debt repayments with regular installments at Financial Institutions in the past year? | Yes/No |

| Budgeting Ability | What is the ratio (N) between expenditure to household net income from a business or main job on average for a month? | 0 ≤ N < 1,1 ≤ N < 2, 2 ≤ N < 3, N ≥ 3 |

| Resilience to Financial Shocks | Length of time deposit/savings/deposit and cash deposits at a household that can cover the cost of living if the household loses its main source of income? | ≥12 months, 6–12 months, 3–6 months, 1–3 months, ≤ 1 month |

| Participation in Basic Social Activities (Social Exclusion) | Does household have the expenditure to be able to participate in basic social activities such as recreational, entertainment or hobby needs in the past year? | Yes/No |

Indicator of FVI Compiler based on Subjective Approach.

| Indicator | Inquiries | Response |

|---|---|---|

| Meeting Ends | In the past year, has household ever had trouble in meeting life’s needs? | Yes/No |

| Debt Solvency | In the past year, has household ever had trouble in paying debts? | Yes/No |

| Perception of Income Shock | If household loses its main source of income, how long can savings (e.g. demand deposits, savings and deposits) and household cash continue to cover the cost of living? | ≥12 months, 6–12 months, 3–6 months, 1–3 months, 1 wk - 1 month, ≤ 1 wk |

| Perception of Expenditure Shock | If household has unexpected expenses that must be incurred now, what is the expenditure that can be paid easily without having to cause financial difficulties (in rupiah)? | ≥50 million, Max.50 million, Max. 25 million, Max. 10 million, Max.5 million, Max. 1 million Max 500 tho |

| Perception of change income conditions Relative of last year | According to respondents, how is the condition of household income this year relatively compared to the previous year? | Worse, The same, Better |

-

1)

Debt Ownership Households are considered vulnerable when they need debt to finance basic needs or daily expenses (Vandone, 2009) and need debt to finance business needs.

-

2)

Ownership of Arrears household is considered a range when there are arrears on debt.

-

3)

Household’s Budgeting Ability is considered vulnerable when the household budget and income tend to be in deficit conditions (Anderloni et al., 2012).

-

4)

Resistance to Financial Shocks (Resilience) Households are considered vulnerable when they are unable to finance unexpected expenses and previously there is no anticipation plan (Jappeli et al., 2008).

-

5)

The issuance of Basic Social Activities (Household Social Exclusion) is considered vulnerable when they do not have sufficient financial capacity to finance household basic social activities (Worthington, 2006).

Source: Questionnaire for Balance Sheet Survey, Bank Indonesia.

Appendix 3.

Table 4.

Accumulative Score Value of the FVI. This table report the accumulative score of Financial Vulnerabilities Index based on Objectives (Debt, Arrears, Budgeting Skills, Financial Resilience, and Social Exclusion) and Subjective (Meeting Ends, Debt Solvency, Perception of Income Shock, Perception of Expenditure Shock and Perception of Change Income Condition relative to Last Year). For Each FVI, we report, total observation, average, standard deviation, Min and Max Value.

| Index | Obs. | Average | Std.Dev. | Min. Value | Max. Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FVI Objectives – 2016 | 3.500 | −1.19e-08 | 1.365 | −3.026 | 2.385 |

| FVI Objectives – 2017 | 3.500 | 1.62e-08 | 1.379 | −2.776 | 2.583 |

| FVI Subjectives – 2016 | 4.000 | 1.86e-08 | 1.952 | −6.065 | 3.947 |

| FVI Subjectives – 2017 | 4.000 | −4.27e-08 | 2.010 | −4.117 | 3.995 |

References

- Abubakar A., Astuti R., Oktapiani R. 2017. Instrument Kebijakan Makroprudensial di Sektor Properti: Kajian Penerapan Batasan Rasio Debt to Income (DTI) di Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakar A., Astuti R., Oktapiani R. The analysis of risk profile and financial vulnerability of households in Indonesia. Buletin Ekonomi Moneter Perbankan. 2018;20(4):443–474. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya V., Philippon T., Richardson M., Roubini N. The financial crisis of 2007-2009: causes and remedies. Financ. Mark. Inst. Instrum. 2009;18(2):89–137. [Google Scholar]

- Albacete N., Peter L. 2013. Household Vulnerability in Austria – A Microeconomic Analysis Based on the Household Finance and Consumption Survey; pp. 57–73. Financial Stability Report 25 – (June 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Allison Paul D. Fixed Effects Regression Methods for Longitudinal Data Using SAS®. SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Anderloni L., Bacchiocchi E., Vandone D. Household financial vulnerability: an empirical analysis. Res. Econ. 2012;66:284–296. [Google Scholar]

- Bańbuła P., Kotuła A., Przeworska J., Strzelecki P. Which households are really financially distressed: how MICRO-data could inform the MACRO-prudential policy. In: Bank for International, editor. Vol. 41. Bank for International Settlements; 2015. (Combining Micro and Macro Data for Financial Stability Analysis). [Google Scholar]

- Bańkowskam K. European Central Bank on IFC-NBB Workshop; 2017. Household Vulnerability in the Euro Area. [Google Scholar]

- Cynamon B.Z., Fazzari S.M. Household debt in the consumer age: source of growth--risk of collapse. Capitalism Soc. 2008;3(2) doi: 10.2202/1932-0213.1037. ISSN (Online) 1932-0213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bialowolski P., Weziak-Bialowolska D. The index of household financial condition, combining subjective and objective indicators: an appraisal of Italian households. Soc. Indicat. Res. 2013:365–385. [Google Scholar]

- Cox P., Whitley J., Brierley P. 2002. Financial Pressures in the UK Household Sector: Evidence from the British Household Panel Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Dartanto T., Moeis F.R., Otsubo S. Intragenerational economic mobility in Indonesia: A transition from poverty to middle class during 1993-2014. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 2019:1–57. doi: 10.1080/00074918.2019.1657795. In press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dartanto T., Shigeru O. 2016. Intrageneration Poverty Dynamics in Indonesia: Households’ Welfare Mobility before, during, and after the Asian Financial Crisis. JICA Working Paper No. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Dey S., Djoudad R., Terajima Y. Bank of Canada Review; 2008. A Tool for Assessing Financial Vulnerabilities in the Household Sector. [Google Scholar]

- Djoudad R. 2012. A Framework to Assess Vulnerabilities Arising from Household Indebtedness Using Microdata. Bank of Canada Discussion Paper 3. [Google Scholar]

- Girouard N., Kennedy M., André C. Has the Rise in Debt Made Households More Vulnerable? OECD Publishing; Paris: 2006. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 535. [Google Scholar]

- Handayani D., Salamah U., Yusacc R.N. Indebtedness and subjective financial welfare of households in Indonesia. Econ. Finan. Indonesia. 2016;62(2):78–87. [Google Scholar]

- Jappelli T., Pagano M., Di Maggio M. vol. 208. 2008. (Households’ indebtedness and financial fragility). CSEF Working Papers. [Google Scholar]

- David Kotz M. The financial and economic crisis of 2008: A systemic crisis of neoliberal capitalism. Rev. Radic. Polit. Econ. 2009;41(Issue 3):305–317. [Google Scholar]

- Leika M., Marchettini D. 2017. A Generalized Framework for the Assessment of Household Financial Vulnerability. IMF Working Paper, WP/17/228. [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y., Martin F.G. Household life cycle protection: life insurance holdings, financial vulnerability, and portfolio implication. J. Risk Insur. 2007;4(No.1):141–173. [Google Scholar]

- May O., Tudela M., Young G. Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin; Winter: 2004. British Household Indebtedness and Financial Stress: A Household -level Picture; pp. 414–428. [Google Scholar]

- Mian A., Sufi A., Verner E. 2017. How Does Credit Supply Expansion Affect the Real Economy? the Productive Capacity and Household Demand Channels. [Google Scholar]

- Mian A., Sufi A. House prices, home equity-based borrowing, and the US household leverage crisis. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011;101 [Google Scholar]

- Nucu A.E. Household sector and monetary policy implications: evidence from central and eastern European countries. Proc. Econ. Finan. 2012;3:889–895. [Google Scholar]

- Sachin B.S., Rajashekar V., Dr Ramesh B. Festival spending pattern: its impact on financial vulnerability of rural households. Soc. Work Foot Print. 2018;7(5):48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Vandone D. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2009. Consumer Credit in Europe: Risks and Opportunities of a Dynamic Industry; pp. 1–134. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington A.C. Debt as a source of financial stress in Australian households. J. Consum. Res. 2006;30(1):2–15. [Google Scholar]