Abstract

The goal of screening programs for inborn errors of metabolism (IEM) is early detection and timely intervention to significantly reduce morbidity, mortality and associated disabilities. Phenylketonuria exemplifies their success as neonates are identified at birth and then promptly treated allowing normal neurological development. Lysosomal diseases comprise about 50 IEM arising from a deficiency in a protein required for proper lysosomal function. Typically, these defects are in lysosomal enzymes with the concomitant accumulation of the enzyme’s substrate as the cardinal feature. None of the lysosomal diseases are screened at birth in Australia and in the absence of a family history, traditional laboratory diagnosis of the majority, involves demonstrating a deficiency of the requisite enzyme. Diagnostic confusion can arise from interpretation of the degree of residual enzyme activity causative of disease and is impractical when the disorder is not due to an enzyme deficiency per se. Advances in mass spectrometry technologies has enabled simultaneous measurement of the enzymes’ substrates and their metabolites which facilitates the efficiency of diagnosis. Employing urine chemistry as a reflection of multisystemic disease, individual lysosomal diseases can be identified by a characteristic substrate pattern complicit with the enzyme deficiency. Determination of lipids in plasma allows the diagnosis of a further class of lysosomal disorders, the sphingolipids. The ideal goal would be to measure biomarkers for each specific lysosomal disorder in the one mass spectrometry-based platform to achieve a diagnosis. Confirmation of the diagnosis is usually by identifying pathogenic variants in the underlying gene, and although molecular genetic technologies can provide the initial diagnosis, the biochemistry will remain important for interpreting molecular variants of uncertain significance.

Introduction

Inborn errors of metabolism (IEM) first gained traction in 1908 following the British physician, Sir Archibald E Garrod’s investigations into alkaptonuria, an error in the metabolism of two amino acids, phenylalanine and tyrosine.1 Confirming that this disorder adhered to the pattern of autosomal recessive inheritance, he postulated the cause being a genetic defect in an enzyme involved in the breakdown of proteins. Today there are over 1000 congenital disorders involving abnormalities in biochemical processes that fall under the collective umbrella of IEM with a combined incidence of 1 in 800.2 Single gene disorders inherited as autosomal recessive traits are typical, although dominant and X-linked conditions also exist. Molecular variants in genes that encode enzymes required for proper metabolism are by far the most common cause of IEM, although defects in transporters, ancillary proteins and co-factors are also well-described.3 Clinical manifestations precipitate from the accumulation of the enzyme’s substrate, alternative substrate metabolism or trafficking (which may divert the metabolic flux to other pathways) and/or the downstream consequences of a reduction in the generation of the cellular product. The pathophysiology is complex and likely involves a combination of all aforesaid aspects as the cell tries to maintain homeostasis while harbouring the single metabolic anomaly. The incidence of individual IEM is highly variable ranging from 1 in 1,000,000 to 1 in 4,000 but collectively they constitute about 80% of the cohort of ‘orphan diseases’ and account for a significant portion of childhood disability and death.4

Early diagnosis of treatable IEM is critical in many instances for timely intervention before the onset of irreversible damage and/or premature mortality. The aim of therapy is to restore the metabolic balance and although life-saving dietary restrictions and nutritional supplements are the foundation of treatment, other therapies, aiming to replace the defective protein, reduce the amount of substrate or rescue the function of the defective enzyme, are also in routine use.5 Nonetheless, diagnosing IEM is challenging because disease manifestations are diverse and non-specific, and therefore often confused with more common conditions. One way to achieve a diagnosis is through screening programs, in particular newborn screening for actionable IEM will ensure that infants are diagnosed early, prior to symptomology onset, significantly improving health outcomes and avoiding mortality.

Newborn Screening for IEM

The inauguration of newborn screening in Australia occurred in 1964 for the IEM, phenylketonuria (PKU).6 An inborn error of amino acid metabolism, PKU arises due to an absence of phenylalanine hydroxylase which is the enzyme responsible for the conversion of surplus dietary phenylalanine to tyrosine. Although infants appear normal at birth, symptoms develop slowly over several months due to the toxic accumulation of phenylalanine resulting in severe intellectual disability, the hallmark of PKU. However, treatment soon after birth with dietary phenylalanine restriction, prevents the neurological demise affording normal neurological development.7 PKU exemplifies the power and success of newborn screening for actionable genes and the benefits are remarkable.

Following the introduction of mass spectrometry into the biochemistry laboratory in the 1990s the number of congenital disorders that could be screened increased dramatically, enabling up to 40 individual IEM to be interrogated from the same newborn sample.8 Mass spectrometry is an analytical tool that measures compounds in the gas phase based on their mass-to-charge ratio as either anions or cations. It offers both high precision and sensitivity enabling qualitative and quantitative analytical data on nanomolar to attomolar concentrations of compounds. Importantly, tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) improves the specificity of the compound being measured by using an inert gas to break bonds within the compound of interest producing characteristic fragments and yielding structural information. For a review on mass spectrometry in the biochemistry laboratory the reader is referred to Griffiths et al.9 By way of an example, the sphingolipid class of lipids will all produce the cation of 264 due to the presence of sphingosine. The power of MS/MS lies in the ability to be able to do this for multiple compounds in the same sample at the same time. With the inclusion of stable isotope internal standards, the quantification of the compounds is astoundingly good. Sample preparation of complex biological samples such as plasma and urine, has been simplified by the coupling of liquid chromatography which allows partial separation and therefore clean-up of the sample prior to MS/MS analysis.

One of the major challenges facing newborn screening programs is deciding which IEM should be included. Although the merits of newborn screening for PKU are obvious, no hypothesis driven clinical trials have been documented. The history of the trials and tribulations of newborn screening has been discussed and the debate about what IEM should be included in the newborn screen is ongoing.6,10 The Newborn Bloodspot Screening National Policy Framework has attempted to provide a framework for newborn screening of congenital disorders that defines criteria for inclusion based on a risk/benefit analysis for identifying the IEM at birth.11 For the current list of IEM screened for at birth, it is believed that diagnosis at birth enables early intervention, with a significant improvement in the health outcome of the neonate that would not be possible if the diagnosis was made once the infant developed symptoms of disease, and thus diagnosed at a later date. Currently 29 IEM are screened at birth in Australia but this list is continuing to expand with the ability to identify rare and life threatening conditions at birth to initiate early treatment.12 The lysosomal diseases are one such example.

Lysosomal Diseases

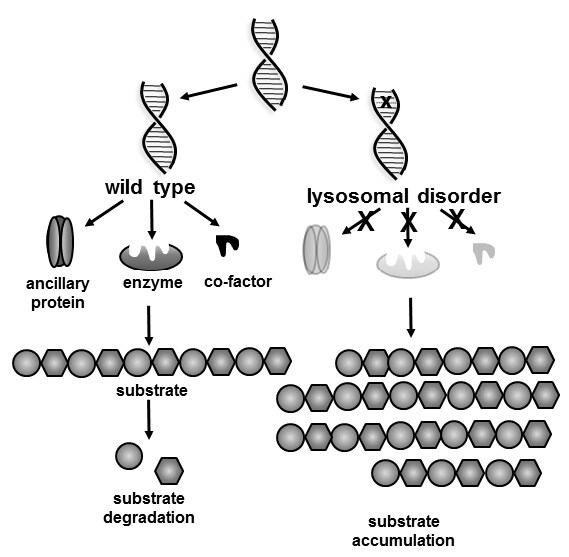

Lysosomal diseases encompass a family of approximately 50 inborn errors of metabolism that manifest physical and often cognitive/neurological disabilities generally leading to premature death. They occur when a lysosomal protein, most commonly an enzyme or transporter, becomes dysfunctional due to pathogenic variants in the encoding gene (Figure 1). Consequently, the substrate for the enzyme or transporter accumulates in intracellular organelles, the lysosomes. Relentless lysosomal storage results in progressive cell, tissue and ultimately organ dysfunction eliciting a broad spectrum of clinical features depending on the nature of the substrate, the tissues involved and the defective protein.13 Onset of symptoms can manifest in the antenatal period typically as nonimmune hydrops fetalis (NIHF) in a continuum through to adulthood. Signs and symptoms can differ even within the same disorder.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the biochemistry of lysosomal diseases. The X on the DNA strand marks the molecular defect resulting in a defective gene product of either an enzyme, ancillary protein (often a transporter) or a cofactor (often required for enzyme activity) which is required for proper metabolism. Consequently, the substrate that cannot be metabolised or transported accumulates resulting in disease.

Together with the broad heterogeneity in clinical presentation, is their rarity, rendering these disorders challenging to diagnose. Often not considered in the differential diagnosis, the non-specific organ symptoms are typically confused with more common conditions.14 Clinical manifestations and age of symptomology onset are varied but indicators could include loss of acquired skills in young children, such as losing the ability to speak, eat and walk, traits that may also accompany symptoms of organ malfunction.15 Progressive cognitive impairment in combination with musculoskeletal abnormalities, cardiac abnormalities, with or without the appearance of ophthalmological features, and umbilical/inguinal herniation, all may pinpoint findings consistent with a lysosomal disease.16 Importantly, although lysosomal diseases frequently come under the umbrella of childhood metabolic disorders, many of them display later-onset phenotypes not manifesting until adulthood, and moreover, have a slower rate of disease progression. In some cases, but certainly not all, pathogenic variants in the disease-causing genes can predict a later-onset form of the classical disease.17,18

Lysosomal diseases have a collective incidence in Australia of 1 in 7,000 and individual incidences ranging from 1 in 60,000 for Gaucher disease to 1 in 1,000,000 for alpha-mannosidosis.19 This prevalence is not dissimilar to that reported in Europe and Canada where the populations share common ancestry.20,21 However, in the United Arab Emirates there is a notably higher incidence of particular lysosomal diseases, for example, alpha-mannosidosis is as high as 1 in 66,000, which is most likely due to founder effects and consanguinity, as most patients are reportedly homozygous for the disease causing-variants.22 Considerably higher frequencies also associate with particular ethnicities, such as the Ashkenazi Jewish population having an incidence of Gaucher disease of 1 in 800.23 There are limited epidemiological studies on the prevalence of lysosomal diseases primarily due to their rarity and the belief that many are under- and mis-diagnosed. It is also noteworthy that figures reported to date precede worldwide newborn screening pilot programs and consequently underrepresent actual prevalence. Since the advent of newborn screening programs, perhaps unsurprisingly, the incidence of individual lysosomal diseases has become much higher than previously reported.24,25

Given that therapies for some lysosomal disorders are now available, identifying patients with a treatable lysosomal disease becomes particularly important as early intervention parallels superior outcomes.26 Raising awareness of these rare disorders so they are considered in the differential diagnosis, is one approach to increase the diagnostic yield, and targeted screening programs for patients considered to be at risk of lysosomal diseases may also help identify patients.27

Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Diseases

Undoubtedly, newborn screening is the most appropriate avenue for diagnosis of lysosomal diseases affording a captive market. However, given the heterogeneity in clinical presentation, the very real quandary of identifying a neonate that will not experience any symptoms of disease until adulthood cannot be ignored. This was particularly noticeable in a region in Italy where newborn screening for Fabry disease reported 10 out of 11 positive cases to be adult-onset.28 In Taiwan, similar results were obtained from newborn screening which predicted that the majority of positive newborn screens for Fabry disease would not manifest symptomology until the fifth decade of life.29 Importantly, pilot newborn screening for five lysosomal diseases, Gaucher, Pompe, Niemann-Pick A/B, Fabry disease and mucopolysaccharidosis type I in New York, identified 23 confirmed positive neonates, all of whom were predicted to have late-onset phenotypes.30

In the United States, the Recommended Universal Screening Panel (RUSP) endorses newborn screening for two lysosomal diseases, Pompe disease and mucopolysacchardosis type I (MPS I). Although not mandatory, these two disorders are included in most state screening programs, although some states are newborn screening for up to seven lysosomal disorders.31 Both Pompe disease and MPS I appear compliant with the criteria for screening set out by RUSP, in that there is evidence to support a potential net benefit of screening, methodology is available to screen, and there is effective treatment. However, both disorders also have a later onset phenotype and identifying neonates at birth, challenges the notion of the ‘net benefit of screening’ as it may take years, or even decades, to determine whether the disease will be clinically expressed. While it is clear that the infantile form of Pompe disease, a severe metabolic myopathy, must be treated early to prevent premature death, and treatment for Hurler syndrome - the neuronopathic form of MPS I – will only have an impact on the rapidly progressing neurological decline if undertaken before 9 months of age, the more common slower progressing phenotypes may not present with any symptoms until adulthood. Indeed, findings from newborn screening programs appear congruent, all identifying far larger numbers of neonates at risk of later- rather than early childhood-onset phenotypes. It is noteworthy testing children for adult-onset genetic diseases is not usually considered appropriate.32

Another contentious issue that warrants consideration is the identification of neonates that, despite follow-up testing - necessary to acquit false positives - the phenotype cannot be defined, committing them to a label of ‘undetermined’. This typically arises when the secondary biochemical testing has been equivocal or normal and these infants have genotypes of unknown significance or onset. In these cases, it is necessary to monitor the developing milestones of these individuals for any indicators of disease manifestations followed by long term surveillance for potential late-onset disorders.28–30, 33–35

Identification of Lysosomal Diseases

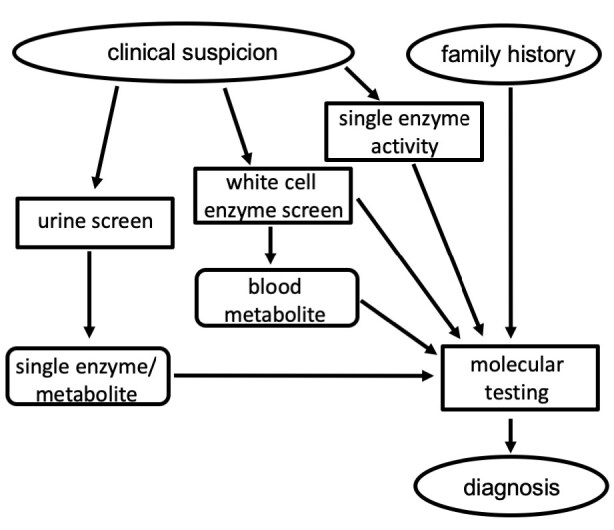

In the absence of newborn screening in Australia, the diagnostic trajectory typically follows clinical suspicion. Given the non-specific clinical presentation and infrequency of these disorders, diagnosis is often protracted and may take several years from first symptom onset to a confirmed laboratory diagnosis.36 The laboratory testing typically begins with broad screening tests that covers a number of lysosomal diseases. Results from this initial screening will then dictate what testing should next be performed to achieve a diagnosis, which is normally subsequently confirmed with the identification of pathogenic variants in the disease-causing genes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart outlining the typical steps involved in the laboratory diagnosis of lysosomal disorders. Of note, if one of the family of sulphatase enzymes is deficient it is necessary to test for another sulphatase to show that it is normal to rule out a diagnosis of multiple sulphatase deficiency.

Substrate Testing in Urine

Similar to other IEM, the disorders are often grouped according to the nature of the accumulating substrate (Table) and this substrate presents an opportunity for first line laboratory testing. This is particularly true for the mucopolysaccharidoses (MPS) and the oligosaccharidosis for which initial testing generally involves the measurement of substrate that is excreted in the urine. Urine is a non-invasive sample to collect and following clinical indicators of an IEM, a urine metabolic screen is frequently performed that nominally includes amino acid quantitation, creatine metabolites, selected purines and pyrimidines, piperidine-6-carboxylate and organic acids. GAG (glycosaminoglycans) measurement often forms part of the metabolic screen providing a first-line investigation for MPS.

Table.

Broad classification and examples of lysosomal diseases.

| Substrate category | Individual disorders | Examples of common symptoms* |

|---|---|---|

| Glycogenosis | Danon disease, Pompe disease | muscle weakness, cardiomyopathy |

| Mucolipidosis | ML types I, II (I-cell disease), III and IV | coarse facial features, short stature, skeletal abnormalities, ± intellectual disability, joint abnormalities |

| Mucopolysaccharidoses | MPS type 1 (Hurler or Scheie), type II (Hunter), type IIIA, B, C and D (Sanfilippo A, B, C, D), type IVA and B (Morquio A and B), type VI (Maroteaux-Lamy), MPS VII (Sly), MPS IX | coarse facial features, hernia, joint restriction, hydrocephalus, short stature, skeletal abnormalities, ± intellectual disability, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis | NCL types 1 to 14 | ataxia, dementia, seizures, retinopathy, blindness |

| Oligosaccharidoses | α- and β-mannosidosis, fucosidosis, sialidosis, sialic acid storage disorder, sialuria, galactosialidosis, Schindlers disease, aspartylglucosaminuria | coarse facial features, dystosis multiplex, short stature, skeletal abnormalities, ± intellectual disability |

| Sphingolipidoses | GM1 and GM2 gangliosidosis, Farber disease, Fabry disease, Gaucher disease, Krabbe disease, metachromatic leukodystrophy, Niemann-Pick A/B and C | neurological disease, gaze palsy, retinopathy (‘cherry red spot’ appearance), acroparesthesia, splenomegaly, cardiomyopathy, renal failure, bone disease |

Manifestations listed are not present in every individual disorder nor shared in patients with the same individual disorder, noting considerable heterogeneity in clinical presentation in lysosomal disorders.

Mucopolysaccharidoses (MPS)

MPS represent a family of lysosomal diseases caused by a specific enzyme deficiency required for the sequential degradation of complex macromolecules, GAG. Consequently, incompletely digested GAG accumulates in the lysosomes of affected cells causing progressive tissue and organ damage. There are 11 known enzyme deficiencies resulting in seven distinct MPS disorders. Composite in the metabolic screen, urinary GAG is typically measured by colorimetric detection using the 1,9-dimethylene blue reaction.37 If elevated this quantitative analysis is followed by electrophoresis which enables partial separation of the different GAG types, being heparan sulphate, dermatan sulphate, chondroitin sulphate and keratan sulphate.38 Despite this dye binding assay being a quick and simple test to determine whether an MPS disorder may be indicated, it suffers from a lack of sensitivity and specificity. False positive results are not uncommon due to interfering substances and there is a considerable risk of false negative results especially in patients with less aggressive forms of MPS III and IV, especially in adults.39 To address this, a number of methods have been developed to increase both the sensitivity and specificity of GAG screening tests for MPS. Depolymerisation of GAG into smaller fragments using commercially available bacterial lyases allows detection of these low molecular weight GAG fragments by mass spectrometry. By incorporation of internal standards, it is possible to reliably quantify the concentration of these fragments and such an approach affords increased sensitivity for the detection of storage material. This has allowed identification of MPS types not only in urine but also in blood, with the exception of MPS IV where the specific type of GAG accumulating in this disorder was not amenable to depolymerisation.40 Methanolysis is another approach for breaking down the high molecular weight GAG into smaller fragments for mass spectrometric detection and this method has been able to identify MPS III and IV patients in whom urinary GAG was normal.41 The characteristic non-reducing end unique to the enzyme deficiency can also be generated by enzymatic depolymerisation releasing subunits that can be measured by mass spectrometry.42

Urine creatinine is often used as the normaliser to correct for urine output, but because urinary GAG concentrations are not static, age-related reference ranges are required. This is particularly important in younger patients as urinary GAG concentrations often normalise once children finish growing masking the diagnosis of MPS. Another study has shown that GAG fragments gave more consistent measurements when normalised to another urinary GAG, chondroitin sulphate, rather than to creatinine as they were less sensitive to fluctuations in physiological conditions or age.43

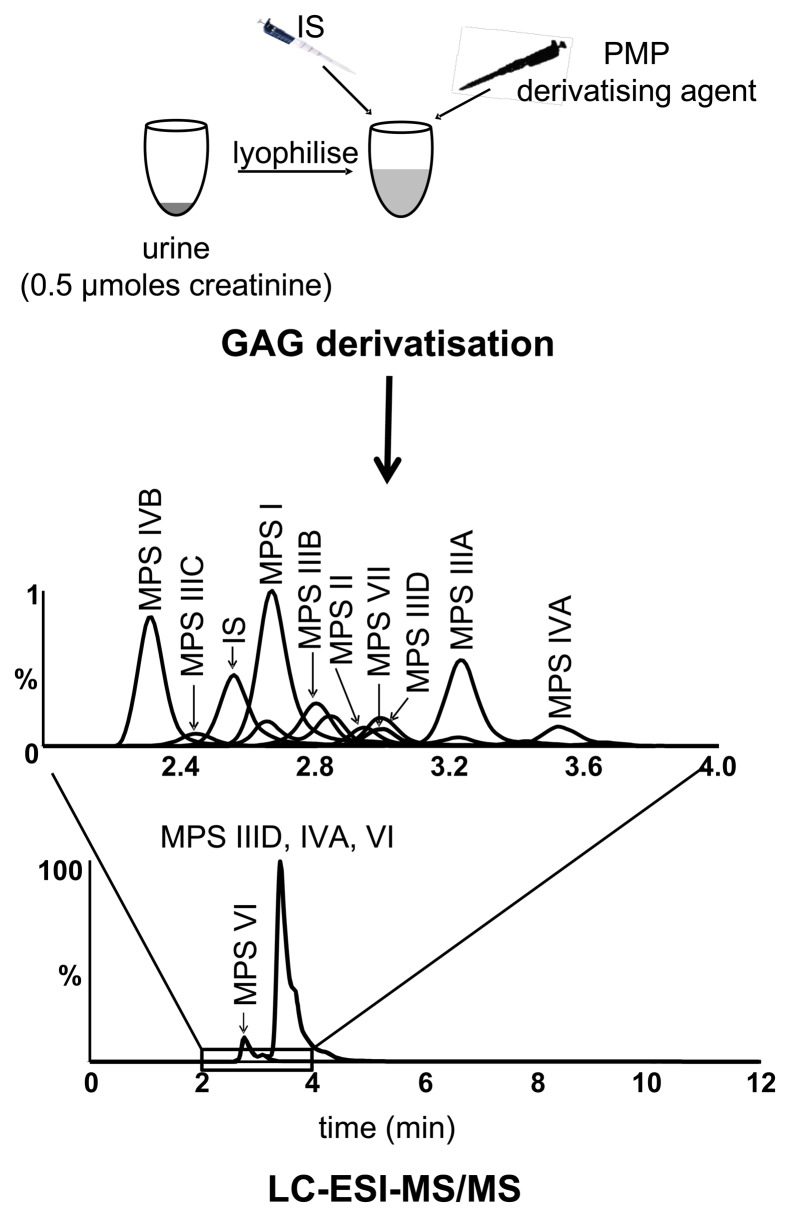

Our laboratory developed a urinary mass spectrometric method for the non-reducing end that measures the native GAG fragments without requiring enzymatic or chemical digestion.44 This is based on the premise that GAG exists in a gradient of sized fragments from monosaccharides through to high molecular weight polysaccharides.45 Each MPS type will have a specific non-reducing end reflective of the enzyme deficiency and although the larger GAG fragments will not be able to be measured by mass spectrometry, the smaller ones are of a similar size to those generated by depolymerisation.46 Making use of a derivatising agent, 1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone, to facilitate detection by mass spectrometry, this allows quantification of the native low molecular weight GAG - di- to tetrasaccharides - with non-reducing termini unique for each enzyme deficiency (Figure 3). This approach allows identification of all 10 subtypes, with the exception of MPS IX which has not yet been tested and this method has been running in our diagnostic service since receiving NATA accreditation in 2017.44

Figure 3.

Mass spectrometry to identify each subtype of mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) in urine. GAG, glycosaminoglycans; LC-ESI-MS/MS, liquid chromatography-electrospray ionisation-tandem mass spectrometry; IS, internal standard; PMP, 1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone.

Oligosaccharidoses

Mass spectrometry is also beginning to replace traditional thin layer chromatography (TLC) urine screening for another class of lysosomal disorders, the oligosaccharidoses. These disorders arise from a hydrolase defect in the degradation of O-linked or N-linked oligosaccharides and consequently these oligosaccharides are excreted in urine. The TLC method used in our laboratory also relies on creatinine as a corrector for urine output and involves spotting a known amount of creatinine onto the plate.47 Following separation of the oligosaccharides, the chromatogram is first sprayed with a resorcinol reagent allowing for visualisation of oligosaccharides with sialic acid at the non-reducing end. A second spray with orcinol allows for visualisation of the remaining oligosaccharides based on the hexose residue. This method is used for initial screening of sialidosis, sialic acid storage disorder, sialuria, galactosialidosis and aspartylglucosaminuria. The GM1 and GM2 gangliosidoses, α-mannosidosis, fucosidosis, I-cell disease and Schindler disease also have characteristic urinary oligosaccharide excretion although these disorders are included in the white cell enzyme screen (see ‘Leukocyte testing’). Theoretically identifiable, β-mannosidosis has not been known to be detectable by TLC. Figure 4 shows an example of a TLC plate with the characteristic oligosaccharide pattern in an α-mannosidosis and sialidosis patient.

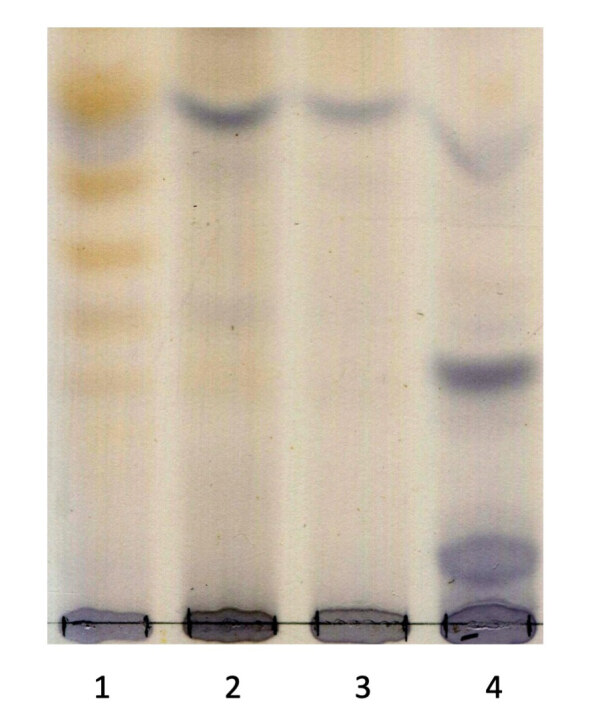

Figure 4.

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) of oligosaccharide patterns in urine samples. Lane 1, α-mannosidosis patient; Lane 2 and 3, unaffected; Lane 4, sialidosis patient.

The major limitations of the TLC method include poor sensitivity and specificity, and no structural information on the oligosaccharides is returned, which is often helpful for the diagnosis. Importantly, some patients, most often those with a more attenuated phenotype, return an oligosaccharide profile that is too faint to detect on a TLC plate.48 Just like the MPS fragments, derivatisation of these oligosaccharides can be undertaken enabling detection by mass spectrometry.49 As this relies on a terminal reducing sugar for derivatisation, it will miss aspartylglucosaminuria which has a glycoamino acid at the reducing end. Matrix assisted-laser desorption/ionisation - time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry provided some structural detail on the oligosaccharides that are in the urine from these patients and these analytical experiments paved the way for a routine assay to be developed.50 Transfer of the methodology onto a conventional tandem mass spectrometry has afforded increased sensitivity, without the requirement for derivatisation, enabling the later onset oligosaccharidoses patients to be identified who would have been missed using traditional TLC.51

The lack of commercially available standards appropriate for absolute quantification of these oligosaccharides means that structurally similar compounds are used as substitutes. Therefore reported concentrations for the MPS and oligosaccharidosis are relative to the internal standard used only. Although this is usually sufficient for diagnosis, using these relative concentrations as an assessment of disease burden or to biochemically monitor the response to therapeutic interventions must be interpreted within the limitations of the standards used. Ideally an internal standard would be a stable isotope, such that, its behaviour in the analytical process, mirrors the compound measured, but the mass difference is sufficient for mass spectrometric detection. The generation of calibration curves is also difficult because this would require the specific oligosaccharide for each MPS type and oligosaccharidosis to be synthesised as pure compounds for use as standards. A notable exception, with an authentic internal standard commercially available, is sialic acid storage disorder, one of the oligosaccharidosis characterised by the excretion of free sialic acid in the urine due to defective sialic acid transport out of the lysosome52. The mass spectrometry method uses a stable isotope 1,2,3-13C-sialic acid enabling absolute quantification of urinary sialic acid affording specific and sensitive diagnosis of sialic acid storage disorder.53

Enzymology

Leukocyte Testing

If the initial urine screening is negative, the next test for lysosomal diseases is often a white cell enzyme screen which involves measuring lysosomal enzyme activity in leukocytes isolated from EDTA blood. Different laboratories host a similar repertoire of lysosomal enzymes in their screen but there are subtle differences. One of the drawbacks of the lysosomal enzyme screen is the 6–8 mL of blood that is needed, which is often difficult to collect from sick infants. Our laboratory’s white cell enzyme screen tests for 14 specific lysosomal diseases, α-mannosidosis, ceroid lipofuscinosis neuronal types 1 (infantile) and 2 (late infantile), acid lipase deficiency, Fabry disease, fucosidosis, Gaucher disease, GM1 and GM2 gangliosidosis type 1 (Tay-Sachs disease) and type 2 (Sandhoff disease), Krabbe disease, I-cell disease, metachromatic leukodystrophy, Niemann-Pick A/B and Schindler disease. The majority of these assays determine the enzyme activity by measuring the rate of reaction. Typically, the substrate used is a synthetic analogue harbouring a fluorescent label, most commonly 4-methylumbelliferyl, which is released as a result of the enzyme action. The enzymatic reaction is stopped by the addition of alkaline buffer which greatly enhances the fluorescence of 4-methylumbelliferyl and the intensity of fluorescence is measured.54 I-cell disease is diagnosed based on elevated plasma determinations of lysosomal enzymes most commonly α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase, β-hexosaminidase and α-mannosidase, which should not be confused with their reduced leukocyte activities diagnostic for Schindler disease and α-mannosidosis, respectively.55 For Krabbe disease, acid sphingomyelinase deficiency (Niemann-Pick type A/B) and acid lipase deficiency, these enzymes are measured against a radiolabeled substrate and the radioactivity estimated by liquid scintillation counting.56 To ensure the integrity of the white cells for lysosomal enzyme activity determinations, acid phosphatase is measured in our laboratory as a control enzyme because there is no known disorder associated with a deficiency of this enzyme.54 These enzymes can also be measured in isolation as single tests for each of the individual lysosomal diseases as required, and other samples such as cultured skin fibroblasts - historically the prototypical sample - as well as chorionic villus sampling and amniocytes for prenatal testing are all appropriate for testing.

Dried Blood Spot (DBS) Testing

As the enzyme deficiency is ubiquitous, all cell types are theoretically suitable for diagnostic testing and during recent years dried filter paper blood spots (DBS) have become popular. The use of DBS allows collection of the sample via a simple finger or heel prick eliminating the need for venipuncture and once collected, the samples can be transported to the testing laboratory in the conventional post. Seminal findings by Nestor Chamoles showed that lysosomal enzyme activities were stable in DBS and consequently fluorometric methods for α-galactosidase, β-galactosidase, β-hexosaminidase, α-L-iduronidase, acid sphingomyelinase and β-glucocerebrosidase were developed, enabling the diagnosis of Fabry disease, GM1 and GM2 gangliosidosis, MPS type I, Niemann Pick A/B and Gaucher disease, respectively.57–61

Our laboratory uses the DBS method for the diagnosis of Fabry disease57 and for Pompe disease.62 Although Fabry disease is part of our leukocyte enzyme screen (as described above), we receive a high number of test requests for this condition compared with other lysosomal diseases. This is due to the high incidence of later onset patients that have remained mis- or un-diagnosed. Furthermore, as targeted treatment is available in the form of enzyme replacement therapy, there is strong impetus to identify these patients in cardiac, renal and stroke clinics.63 It is noteworthy that enzyme determinations in blood are typically unreliable for females as α-galactosidase activity is not always below the reference intervals. Identification of a disease-causing variant in the gene is often the only informative laboratory means do identify Fabry heterozygotes. The DBS improves throughput and minimises sample handling time coupled with the benefits of sample collection and transport. To ensure integrity of enzyme activity in the DBS and to avoid false positive results, β-galactosidase is measured as a control enzyme. Pompe disease, being a muscular dystrophy is rarely confused with other lysosomal diseases and also forms a separate DBS test in our laboratory. To selectively measure α-glucosidase, the reaction requires the addition of acarbose to inhibit the activity of maltase-glucoamylase so as not to mask a diagnosis of Pompe disease.64

Measuring enzyme activities by tandem mass spectrometry is also feasible and is widely used in newborn screening programs. The product of the enzyme reaction is quantified against an internal standard and as it is more hydrophobic than the substrate, chromatographic separation is possible to reduce the effect of in-source fragmentation. To increase the number of lysosomal diseases tested for in the one assay, it is possible to incubate the DBS with each of the substrates individually and then combine the mixture for mass spectrometric determinations. This approach, pioneered by Michael Gelb, is continually developing with more lysosomal diseases being added to the mass spectrometric platform. Reports outlining the practicality have recently been reviewed.65,66

Substrate Testing in Blood

Although measuring the defective enzyme for lysosomal diseases - the majority of which arise as a consequence of such, may seem a straightforward approach - it must be noted that it is still not known how much residual enzyme activity is sufficient to prevent disease. This results in diagnostic confusion as individuals with low enzyme activity may be asymptomatic or may have a later onset, more atypical phenotype. This, together with the ability to detect the accumulating substrates resulting from the enzyme deficiency, has afforded the opportunity to measure these compounds in plasma and DBS. For some lysosomal diseases this has been a mere translation of substrate measurements performed from urine to blood. For example, the method described above to measure low molecular weight GAG fragments unique for each MPS type44 has been extended to plasma as well as CSF for diagnosis of MPS III.67 The measurement of GAG in a pilot newborn screening study for MPS has also exemplified an opportunity for the use of DBS as well.68

The narrative with Fabry disease provides a good illustration for the translation of substrate measurements in urine to blood samples. Fabry disease is one of only two of the lysosomal diseases that is X-linked, but unlike its X-linked counterpart MPS type II, females are often symptomatic. A deficiency in the lysosomal hydrolase, α-galactosidase A, results in the accumulation of the sphingolipid, globotriaoslyceramide and for male patients, measurements of this sphingolipid in urine is diagnostic for Fabry disease.69 Females present more of a challenge, with urinary globotriaoslyceramide often normal, and we have demonstrated a ratio of globotriaoslyceramide and related sphingolipids shows some promise for heterozygotes but in a small patient cohort.70 Subsequently, the deacetlyated derivative of globotriaoslyceramide, globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3), was reported to show a greater elevation than globotriaoslyceramide in male Fabry disease patients and concentrations broadly correlated with clinical manifestations of the classical phenotype. Furthermore, there was also a significant improvement in the ability to identify female patients with many patients returning concentrations above the normal range.71,72

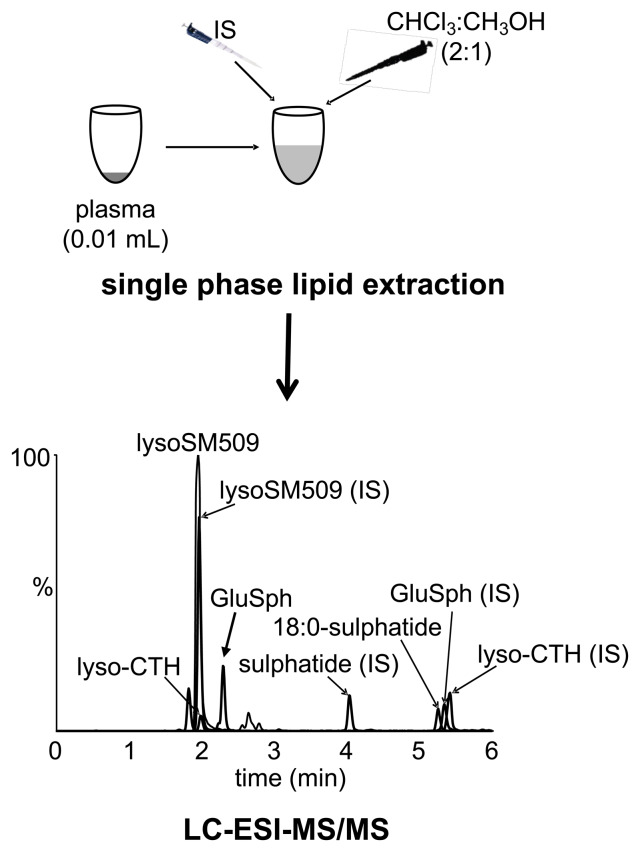

More recently lyso-Gb3 can be reliably measured in plasma and has been demonstrated to be superior over urinary measurements with some females, but not all, returning elevated plasma lyso-Gb3 concentrations.73 Lyso-Gb3 can also be measured in DBS revealing similar results to that seen in plasma.74 Indeed, our laboratory also measures plasma lyso-Gb3 as part of the diagnostic trajectory for Fabry disease, with its primary utility residing with confirmation of a low enzyme result for classical males and for longitudinal biochemical monitoring of therapies. Although we have shown lyso-Gb3 to be helpful for some female patients, returning concentrations above the normal range when enzyme activities have been normal, most heterozygotes and many later-onset hemizygotes have lyso-Gb3 concentrations within the normal reference range.75 Our laboratory has profited from mass spectrometry multiplex technologies and along with lyso-Gb3 determinations, we also measure lyso-Gb1 for the diagnosis of Gaucher disease,76,77 lysoSM509 for Niemann-Pick type C and a single species of sulphatide as a second-tier test for metachromatic leukodystrophy to confirm that a reduced enzyme activity is disease causing and not the result of a pseudodeficiency.78 A schematic of this method is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Multiplex mass spectrometry platform for Fabry disease, Gaucher disease, metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) and Niemann-Pick type C. LC-ESI-MS/MS, liquid chromatography-electrospray ionisation-tandem mass spectrometry; IS, internal standard; lyso-CTH for Fabry disease; lysoSM509 for Niemann-Pick type C; 18:0 sulphatide for MLD; GluSph for Gaucher disease.

Molecular Genetics

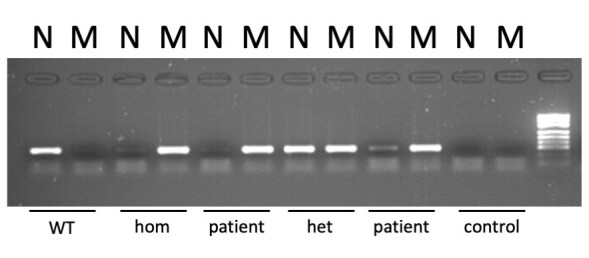

Undoubtedly, identifying known pathogenic variants in the disease-causing gene confirms the diagnosis, and as such provides the ultimate laboratory investigation in the diagnostic trajectory. It also forms the primary diagnostic test when the familial variant is known and in cases where there is no effective biochemical test. A number of approaches are available for uncovering pathogenic variants from simple variant specific assays to next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies. Depending on the gene, the frequency and type of molecular defect, our laboratory employs a range of methodologies. For Gaucher disease by way of example, there are six common variants that account for 70% of the genotype in the Australian population and the most efficient approach for this is amplification-refractory mutation system (ARMS). This involves an allele specific PCR using two primers - one complementary to the normal sequence and the other to the pathogenic variant - requiring complementarity in sequence for amplification to occur.79 Consequently, the wild type sequence will only produce a PCR product with the wild type primer and the mutant sequence with the mutant primer and a heterozygote with both. An example of the ARMS for the most common pathogenic variant in Gaucher disease is shown in Figure 6. A high throughput technology that we use for 12 lysosomal disorders with common pathogenic variants is the MassArray platform. As this is a MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer, it has the inherent ability to be able to test for multiple (up to 90) pathogenic variants in the one gene. Using a locus specific PCR, followed by primer extension with dideoxynucleotide terminators (mass modified) annealing upstream of the variant, the distinct mass of the extended primer identifies the single base change from the mass to charge ratio by mass spectrometric detection.80

Figure 6.

Amplification-refractory mutation system (ARMS) for the identification of the N370S molecular variant in a patient with Gaucher disease. N denotes the PCR with a primer to the wild type (WT) sequence and M for the N370S sequence. WT DNA yields a PCR product with only the N primer, DNA homozygous for N370S yields a PCR product with only the M primer (hom) and heterozygous DNA yields a product with both primers (het). Note the patient is tested in duplicate and analysed in two different lanes on the agarose gel.

If none of the common mutations are found using these approaches, then Sanger sequencing for most lysosomal disease genes is pretty straightforward. A notable exception is Niemann-Pick C (NPC) disease, in which variants in two genes, NPC1 or NPC2, can be causative and given that NPC1 is a large gene at 25 exons, NGS is a more efficient option. NGS platforms overcome the limitations of gene size and number as they are all underpinned by ‘massive parallel sequencing’. Principally, the DNA sample is snipped into fragments and each one sequenced within large arrays at the same time, producing millions of short sequences. Subsequent bioinformatics maps the sequences generated to the reference DNA sample, theoretically enabling the sequencing of the whole exome or genome of selected gene panels.81,82

Efficiency and coverage are varied and will not detect all deletions or duplications. Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) can be helpful for the identification of deletions and duplications as this aligns, ligates and then PCR amplifies adjacent probes on the target DNA. If part of the sequence does not match (due to a deletion or duplication) then no ligation can occur and no PCR product will be produced.83 The major drawback of the increasing power of contemporary NGS that allows for longer reads and more detailed coverage is uncovering variants of uncertain significance (American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics guidelines). Associating particular genetic variants with lysosomal disease is challenging and a notable example is provided with Fabry disease where a single base change at the same residue reportedly results in a spectrum of severity from asymptomatic - monosymptomatic - classical Fabry disease.84

Biomarkers

A biomarker is defined as “a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention”.85 The identification of specific biomarkers and their subsequent validation are where the future lies for definitive, accurate and predictive diagnosis of lysosomal diseases. A biomarker for each lysosomal disease would need to meet all characteristics to be considered ‘ideal’ - that is; the biomarker can be reliably, quickly, reproducibly and cheaply quantifiable in accessible clinical material; and, the biomarker concentration must not be subject to wide variations in the general population, realistically reflect the disease burden and be unaffected by unrelated conditions.86

Numerous biomarkers are reported in the literature, with PubMed returning over 860,000 articles, and ‘biomarker and lysosomal disease’ (1153 articles).87 Biomarker development in the field of lysosomal diseases can be underscored by the clinical utility of glucosylsphingosine for the diagnosis of Gaucher disease. Glucosylsphingosine is the deacetylated form of glucosylceramide, the substrate that accumulates in Gaucher disease due to a deficiency of the lysosomal enzyme acid β-glucocerebrosidsase. As far as meeting the aforesaid biomarker criteria, our laboratory and others have shown that glucosylsphingosine is 100% sensitive and specific for Gaucher disease diagnosis, is easily measured in blood and is stable and robust.76,88,89 It has also been shown to be a pharmacodynamic biomarker responding to therapeutic intervention in a group of homogenous Gaucher disease patients.90 Our laboratory has been using glucosylsphingosine as our first-tier test for Gaucher disease (replacing enzyme activity) for the last five years and have identified 20 patients in whom the diagnosis has been subsequently confirmed by the identification of two pathogenic variants. We have also shown that this biomarker could inform prognostically with neuronopathic patients having significantly higher concentrations in both plasma and DBS compared to patients without neurological manifestations.77 Glucosylsphingosine would therefore appear an ideal biomarker for Gaucher disease, setting a precedent for biomarkers to be developed for other lysosomal diseases that fulfil the desired criteria.

Remaining Challenges

In the absence of an ideal biomarker for every lysosomal disease, the gold standard for diagnosis is still the measurement of the defective gene product, and for the majority this is achieved by determining the enzyme activity. However, diagnosing lysosomal diseases by demonstrating a deficiency in the activity of the requisite enzyme in blood or cells is often not straightforward unless the lysosomal enzyme activity returns a value of zero. Many patients, typically those with a slower progressing phenotype (but not always) will have residual enzyme activity and it is often difficult to ascertain true disease from asymptomatic carriers, pseudodeficiencies and unaffected individuals. In the diagnostic laboratory these issues are partially overcome by follow-up investigations but have been particularly problematic in newborn screening programs, where a neonate is clearly asymptomatic at birth and it is not known whether these newborns will go on to develop disease.28–30, 33–35

Follow-up investigations often require a secondary biochemical test to confirm that the reduced enzyme activity is actually disease-causing, especially in the case of pseudodeficiencies. For example, diagnosis of metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) - a neurodegenerative lysosomal disorder arising from an inability to degrade sulphatides within the lysosome - is confounded by the presence of the enzyme (arylsulphatase A) pseudodeficiency in up to 20% of the population who present with only 5% of residual enzyme activity. However, in these individuals this is sufficient for proper sulphatide catabolism and does not manifest the phenotype of MLD.91 Additionally there is a less common form of MLD due to a deficiency of the enzyme’s activator protein, saposin B, which is required for sulphatide catabolism and these patients will have the MLD phenotype but normal arylsulphatase A activity. To improve the diagnostic trajectory of MLD we developed a simple plasma assay (Figure 5) that measures a particular isoform of sulphatide (18:0) that can be used as an adjunct for the diagnosis of MLD that is normal in patients with the pseudodeficiency and presumably elevated in all patients with MLD.77 Although the final confirmation of diagnosis will require molecular genetic characterisation, the advantage of the plasma assay is that it is far quicker to perform and is not dependent on interpretation of VUS.

Once a diagnosis is achieved, it is important to be able to inform on disease course. Given the wide variety and heterogeneity in clinical course, a diagnosis of a lysosomal disease should be coupled with a prognosis. For some of the lysosomal disorders this is critically important as it dictates treatment and the prototype is MPS I, which has two forms; neuronopathic (Hurler) and non-neuronopathic (Scheie, Table). Enzyme replacement therapy is available for MPS I, but the recombinant protein is too large to cross the blood brain barrier rendering it ineffective for Hurler, and patients with this form of MPS I are typically transplanted.92,93 Given MPS I is listed on the RUSP (see section ‘Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Diseases’) predicting whether the neonate will have Hurler or Scheie is paramount for treatment. Although we showed that prediction of phenotype is possible in cultured skin fibroblasts from MPS I patients, this method required long term cultures and therefore is not efficient to provide a timely prognosis.94 This is clearly an area for future investigations and biomarker development to be able to predict the disease course at the time of diagnosis for all lysosomal diseases will be of significant benefit.

Many are of the opinion that NGS technologies - which are becoming increasingly faster and cheaper - will form the mainstay of laboratory testing for lysosomal diseases. However, with inherent variation in the human genome it is frequently difficult to ascertain pathogenic genetic variants from non-pathogenic. This can usually be overcome by biochemical assays that show whether the gene is producing a functional protein or otherwise, ensuring the importance of biochemical genetics in the field of lysosomal diseases and IEM more broadly. Therefore, the real challenges of diagnosing lysosomal diseases comes with interpretation of VUS, not fully appreciating how much enzyme is sufficient to avert clinical manifestations and the disparity in clinical presentations.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Jennifer Saville for assistance with figures, Janice Fletcher for helpful discussions and the laboratory staff within Genetics and Molecular Pathology.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Garrod AE. Inborn errors of metabolism; the Croonian lectures delivered before the Royal College of Physicians of London, in June, 1908. London: Oxford University Press; 1909. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferreira CR, van Karnebeek CDM, Vockley J, Blau N. A proposed nosology of inborn errors of metabolism. Genet Med. 2019;21:102–106. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0022-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saudubray JM, Mochel F, Lamari F, Garcia-Cazorla A. Proposal for a simplified classification of IMD based on a pathophysiological approach: a practical guide for clinicians. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2019;42:706–727. doi: 10.1002/jimd.12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waters D, Adeloye D, Woolham D, Wastnedge E, Patel S, Rudan I. Global birth prevalence and mortality from inborn errors of metabolism: a systematic analysis of the evidence. J Glob Health. 2018;8:021102. doi: 10.7189/jogh.08.021102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gambello MJ, Li H. Current strategies for the treatment of inborn errors of metabolism. J Genet Genomics. 2018;45:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilcken B, Wiley V. Fifty years of newborn screening. J Paediatr Child Health. 2015;51:103–107. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leonard JV, Morris AA. Inborn errors of metabolism around time of birth. Lancet. 2000;356:583–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02591-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey DB, Jr, Gehtland L. Newborn screening: evolving challenges in an era of rapid discovery. JAMA. 2015;313:1511–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffiths WJ, Jonsson AP, Liu S, Rai DK, Wang Y. Electrospray and tandem mass spectrometry in biochemistry. Biochem J. 2001;355:545–61. doi: 10.1042/bj3550545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollitt RJ. Introducing new screens: why are we all doing different things? J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30:423–9. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0647-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newborn Bloodspot Screening National Policy Framework. [Accessed 10 March 2020]. http://www.cancerscreening.gov.au/internet/screening/publishing.nsf/Content/C79A7D94CB73C56CCA257CEE0000EF35/$File/12118_Newborn%20Bloodspot%20Framework_V4_WEB.PDF.

- 12.Genomics in general practice. Newborn screening. [Accessed 10 November 2019]. https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/genomics-in-general-practice/newborn-screening.

- 13.Ballabio A, Gieselmann V. Lysosomal disorders: from storage to cellular damage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:684–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kishnani PS, Amartino HM, Lindberg C, Miller TM, Wilson A, Keutzer J Pompe Registry Boards of Advisors. Timing of diagnosis of patients with Pompe disease: data from the Pompe registry. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:2431–43. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilcox WR. Lysosomal storage disorders: the need for better pediatric recognition and comprehensive care. J Pediatr. 2004;144:S3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wraith JE. The clinical presentation of lysosomal storage disorders. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2004;13:101–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavalle L, Thomas AS, Beaton B, Ebrahim H, Reed M, Ramaswami U, et al. Phenotype and biochemical heterogeneity in late onset Fabry disease defined by N215S mutation. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0193550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rairikar MV, Case LE, Bailey LA, Kazi ZB, Desai AK, Berrier KL, et al. Insight into the phenotype of infants with Pompe disease identified by newborn screening with the common c.-32-13T>G “late-onset” GAA variant. Mol Genet Metab. 2017;122:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meikle PJ, Hopwood JJ, Clague AE, Carey WF. Prevalence of lysosomal storage disorders. JAMA. 1999;281:249–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuller M, Meikle PJ, Hopwood JJ. Epidemiology of lysosomal storage disorders: an overview. In: Mehta A, Beck M, Sunder-Plassmann G, editors. Fabry disease: perspectives from 5 years of FOS. Oxford: Oxford PharmaGenesis; 2006. pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kingma SDK, Bodamer OA, Wijburg FA. Epidemiology and diagnosis of lysosomal storage disorders; challenges of screening. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;29:145–57. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Jasmi FA, Tawfig N, Berniah A, Ali BR, Taleb M, Hertecant JL, et al. Prevalence and novel mutations of lysosomal storage disorders in United Arab Emirates: LSD in UAE. JIMD Rep. 2013;10:1–9. doi: 10.1007/8904_2012_182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuckerman S, Lahad A, Shmueli A, Zimran A, Peleg L, Orr-Urtreger A, et al. Carrier screening for Gaucher disease: lessons for low-penetrance, treatable diseases. JAMA. 2007;298:1281–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.11.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mechtler TP, Stary S, Metz TF, De Jesús VR, Greber-Platzer S, Pollak A, et al. Neonatal screening for lysosomal storage disorders: feasibility and incidence from a nationwide study in Austria. Lancet. 2012;379:335–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61266-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott CR, Elliott S, Buroker N, Thomas LI, Keutzer J, Glass M, et al. Identification of infants at risk for developing Fabry, Pompe, or mucopolysaccharidosis-I from newborn blood spots by tandem mass spectrometry. J Pediatr. 2013;163:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen HH, Sawamoto K, Mason RW, Kobayashi H, Yamaguchi S, Suzuki Y, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy for mucopolysaccharidoses; past, present, and future. J Hum Genet. 2019;64:1153–71. doi: 10.1038/s10038-019-0662-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Capuano I, Garofalo C, Buonanno P, Pinelli M, Di Risi T, Feriozzi S, et al. Identifying Fabry patients in dialysis population: prevalence of GLA mutations by renal clinic screening, 1995–2019. J Nephrol. 2019 Oct 24; doi: 10.1007/s40620-019-00663-6. [Online ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spada M, Pagliardini S, Yasuda M, Tukel T, Thiagarajan G, Sakuraba H, et al. High incidence of later-onset Fabry disease revealed by newborn screening. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:31–40. doi: 10.1086/504601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin HY, Chong KW, Hsu JH, Yu HC, Shih CC, Huang CH, et al. High incidence of the cardiac variant of Fabry disease revealed by newborn screening in the Taiwan Chinese population. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:450–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.862920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wasserstein MP, Caggana M, Bailey SM, Desnick RJ, Edelmann L, Estrella L, et al. The New York pilot newborn screening program for lysosomal storage diseases: report of the first 65,000 infants. Genet Med. 2019;21:631–40. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0129-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelb MH. Newborn screening for lysosomal storage diseases: methodologies, screen positive rates, normalization of datasets, second tier tests, and post-analysis tools. Int J Neonatal Screen. 2018;4:23. doi: 10.3390/ijns4030023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Botkin JR, Belmont JW, Berg JS, Berkman BE, Bombard Y, Holm IA, et al. Points to consider: ethical, legal, and psychosocial implications of genetic testing in children and adolescents. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97:6–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burton BK, Charrow J, Hoganson GE, Waggoner D, Tinkle B, Braddock SR, et al. Newborn screening for lysosomal storage disorders in Illinois: the initial 15-month experience. J Pediatr. 2017;190:130–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hwu WL, Chien YH, Lee NC, Chiang SC, Dobrovolny R, Huang AC, et al. Newborn screening for Fabry disease in Taiwan reveals a high incidence of the later-onset GLA mutation c.936+919G>A (IVS4+919G>A) Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1397–405. doi: 10.1002/humu.21074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hopkins PV, Klug T, Vermette L, Raburn-Miller J, Kiesling J, Rogers S. Incidence of 4 lysosomal storage disorders from 4 years of newborn screening. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:696–7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Filocamo M, Morrone A. Lysosomal storage disorders: molecular basis and laboratory testing. Hum Genomics. 2011;5:156–69. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-5-3-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gray G, Claridge P, Jenkinson L, Green A. Quantitation of urinary glycosaminoglycans using dimethylene blue as a screening technique for the diagnosis of mucopolysaccharidoses: an evaluation. Ann Clin Biochem. 2007;44:360–3. doi: 10.1258/000456307780945688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wessler E. Analytical and preparative separation of acidic glycosaminoglycans by electrophoresis in barium acetate. Anal Biochem. 1968;26:439–44. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mabe P, Valiente A, Soto V, Cornejo V, Raimann E. Evaluation of reliability for urine mucopolysaccharidosis screening by dimethylmethylene blue and Berry spot tests. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;345:135–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan SA, Mason RW, Giugliani R, Orii K, Fukao T, Suzuki Y, et al. Glycosaminoglycans analysis in blood and urine of patients with mucopolysaccharidosis. Mol Genet Metab. 2018;125:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Auray-Blais C, Lavoie P, Tomatsu S, Valayannopoulos V, Mitchell JJ, Raiman J, et al. UPLC-MS/MS detection of disaccharides derived from glycosaminoglycans as biomarkers of mucopolysaccharidoses. Anal Chim Acta. 2016;936:139–48. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2016.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawrence R, Brown JR, Al-Mafraji K, Lamanna WC, Beitel JR, Boons GJ, et al. Disease-specific non-reducing end carbohydrate biomarkers for mucopolysaccharidoses. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:197–204. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin HY, Lo YT, Wang TJ, Huang SF, Tu RY, Chen TL, et al. Normalization of glycosaminoglycan-derived disaccharides detected by tandem mass spectrometry assay for the diagnosis of mucopolysaccharidosis. Sci Rep. 2019;9:10755. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46829-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saville JT, McDermott BK, Fletcher JM, Fuller M. Disease and subtype specific signatures enable precise diagnosis of the mucopolysaccharidoses. Genet Med. 2019;21:753–7. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0136-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Byers S, Rozaklis T, Brumfield LK, Ranieri E, Hopwood JJ. Glycosaminoglycan accumulation and excretion in the mucopolysaccharidoses: characterization and basis of a diagnostic test for MPS. Mol Genet Metab. 1998;65:282–90. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1998.2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fuller M, Chau A, Nowak RC, Hopwood JJ, Meikle PJ. A defect in exodegradative pathways provides insight into endodegradation of heparan and dermatan sulfates. Glycobiology. 2006;16:318–25. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sewell AC. An improved thin-layer chromatographic method for urinary oligosaccharide screening. Clin Chim Acta. 1979;92:411–4. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(79)90221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raymond K, Rinaldo P. From art to science: oligosaccharide analysis by maldi-tof mass spectrometry finally replaces 1-dimensional thin-layer chromatography. Clin Chem. 2013;59:1297–8. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.208793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sowell J, Wood T. Towards a selected reaction monitoring mass spectrometry fingerprint approach for the screening of oligosaccharidoses. Anal Chim Acta. 2011;686:102–6. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2010.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bonesso L, Piraud M, Caruba C, Van Obberghen E, Mengual R, Hinault C. Fast urinary screening of oligosaccharidoses by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:19. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Piraud M, Pettazzoni M, Menegaut L, Caillaud C, Nadjar Y, Vianey-Saban C, et al. Development of a new tandem mass spectrometry method for urine and amniotic fluid screening of oligosaccharidoses. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2017;31:951–63. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verheijen FW, Verbeek E, Aula N, Beerens CE, Havelaar AC, Joosse M, et al. A new gene, encoding an anion transporter, is mutated in sialic acid storage diseases. Nat Genet. 1999;23:462–5. doi: 10.1038/70585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van der Ham M, Prinsen BH, Huijmans JG, Abeling NG, Dorland B, Berger R, et al. Quantification of free and total sialic acid excretion by LC-MS/MS. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;848:251–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kolodny EH, Mumford RA. Human leukocyte acid hydrolases: characterization of eleven lysosomal enzymes and study of reaction conditions for their automated analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 1976;70:247–57. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(76)90426-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Den Tandt WR, Lassila E, Philippart M. Leroy’s l-cell disease: markedly increased activity of plasma acid hydrolases. J Lab Clin Med. 1974;83:403–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raghavan S, Krusell A. Optimal assay conditions for enzymatic characterization of homozygous and heterozygous twitcher mouse. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;877:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(86)90111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chamoles NA, Blanco M, Gaggioli D. Fabry disease: enzymatic diagnosis in dried blood spots on filter paper. Clin Chim Acta. 2001;308:195–6. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(01)00478-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chamoles NA, Blanco MB, Iorcansky S, Gaggioli D, Spécola N, Casentini C. Retrospective diagnosis of GM1 gangliosidosis by use of a newborn-screening card. Clin Chem. 2001;47:2068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chamoles NA, Blanco MB, Gaggioli D, Casentini C. Hurler-like phenotype: enzymatic diagnosis in dried blood spots on filter paper. Clin Chem. 2001;47:2098–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chamoles NA, Blanco M, Gaggioli D, Casentini C. Gaucher and Niemann-Pick diseases--enzymatic diagnosis in dried blood spots on filter paper: retrospective diagnoses in newborn-screening cards. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;317:191–7. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(01)00798-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chamoles NA, Blanco M, Gaggioli D, Casentini C. Tay-Sachs and Sandhoff diseases: enzymatic diagnosis in dried blood spots on filter paper: retrospective diagnoses in newborn-screening cards. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;318:133–7. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(02)00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chamoles NA, Niizawa G, Blanco M, Gaggioli D, Casentini C. Glycogen storage disease type II: enzymatic screening in dried blood spots on filter paper. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;347:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakagawa N, Sawada J, Sakamoto N, Takeuchi T, Takahashi F, Maruyama JI, et al. High-risk screening for Anderson-Fabry disease in patients with cardiac, renal, or neurological manifestations. J Hum Genet. 2019;64:891–8. doi: 10.1038/s10038-019-0633-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang H, Kallwass H, Young SP, Carr C, Dai J, Kishnani PS, et al. Comparison of maltose and acarbose as inhibitors of maltase-glucoamylase activity in assaying acid alpha-glucosidase activity in dried blood spots for the diagnosis of infantile Pompe disease. Genet Med. 2006;8:302–6. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000217781.66786.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schielen PCJI, Kemper EA, Gelb MH. Newborn screening for lysosomal storage diseases: a concise review of the literature on screening methods, therapeutic possibilities and regional programs. Int J Neonatal Screen. 2017;3:6. doi: 10.3390/ijns3020006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Robinson BH, Gelb MH. The importance of assay imprecision near the screen cutoff for newborn screening of lysosomal storage diseases. Int J Neonatal Screen. 2019;5:17. doi: 10.3390/ijns5020017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saville JT, Flanigan KM, Truxal KV, McBride KL, Fuller M. Evaluation of biomarkers for Sanfilippo syndrome. Mol Genet Metab. 2019;128:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kubaski F, Mason RW, Nakatomi A, Shintaku H, Xie L, van Vlies NN, et al. Newborn screening for mucopolysaccharidoses: a pilot study of measurement of glycosaminoglycans by tandem mass spectrometry. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2017;40:151–8. doi: 10.1007/s10545-016-9981-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mills K, Morris P, Lee P, Vellodi A, Waldek S, Young E, et al. Measurement of urinary CDH and CTH by tandem mass spectrometry in patients hemizygous and heterozygous for Fabry disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2005;28:35–48. doi: 10.1007/s10545-005-5263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fuller M, Sharp PC, Rozaklis T, Whitfield PD, Blacklock D, Hopwood JJ, et al. Urinary lipid profiling for the identification of Fabry hemizygotes and heterozygotes. Clin Chem. 2005;51:688–94. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.041418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Aerts JM, Groener JE, Kuiper S, Donker-Koopman WE, Strijland A, Ottenhoff R, et al. Elevated globotriaosylsphingosine is a hallmark of Fabry disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2812–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712309105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rombach SM, Dekker N, Bouwman MG, Linthorst GE, Zwinderman AH, Wijburg FA, et al. Plasma globotriaosylsphingosine: diagnostic value and relation to clinical manifestations of Fabry disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:741–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nowak A, Mechtler TP, Desnick RJ, Kasper DC. Plasma LysoGb3: a useful biomarker for the diagnosis and treatment of Fabry disease heterozygotes. Mol Genet Metab. 2017;120:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nowak A, Mechtler T, Kasper DC, Desnick RJ. Correlation of Lyso-Gb3 levels in dried blood spots and sera from patients with classic and Later-Onset Fabry disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2017;121:320–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Talbot A, Nicholls K, Fletcher JM, Fuller M. A simple method for quantification of plasma globotriaosylsphingosine: utility for Fabry disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2017;122:121–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fuller M, Szer J, Stark S, Fletcher JM. Rapid, single-phase extraction of glucosylsphingosine from plasma: a universal screening and monitoring tool. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;450:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Saville JT, McDermott BK, Chin SJ, Fletcher JM, Fuller M. Expanding the clinical utility of glucosylsphingosine for Gaucher disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2019 Nov 9; doi: 10.1002/jimd.12192. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Saville JT, Smith NJC, Fletcher JM, Fuller M. Quantification of plasma sulfatides by mass spectrometry: utility for metachromatic leukodystrophy. Anal Chim Acta. 2017;955:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mistry PK, Smith SJ, Ali M, Cox TM, Hatton CS, McIntyre N. Genetic diagnosis of Gaucher’s disease. Lancet. 1992;339:889–92. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90928-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jurinke C, van den Boom D, Cantor CR, Köster H. The use of MassARRAY technology for high throughput genotyping. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2002;77:57–74. doi: 10.1007/3-540-45713-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Metzker ML. Sequencing technologies - the next generation. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:31–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hoffman JD, Greger V, Strovel ET, Blitzer MG, Umbarger MA, Kennedy C, et al. Next-generation DNA sequencing of HEXA: a step in the right direction for carrier screening. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2013;1:260–8. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schouten JP, McElgunn CJ, Waaijer R, Zwijnenburg D, Diepvens F, Pals G. Relative quantification of 40 nucleic acid sequences by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fuller M, Mehta A. Fabry cardiomyopathy: missing links from genotype to phenotype. Heart. 2019 doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2019-316143. Published Online First: 16 January 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Biomarkers Definitions Working Group. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;69:89–95. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.113989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bobillo Lobato J, Jiménez Hidalgo M, Jiménez Jiménez LM. Biomarkers in lysosomal storage diseases. Diseases. 2016;4:40. doi: 10.3390/diseases4040040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.U.S. National Library of Medicine. [Accessed 3 December 2019]. PubMed. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=biomarker+and+lysosomal+disease.

- 88.Dekker N, van Dussen L, Hollak CEM, Overkleeft H, Scheij S, Ghauharali K, et al. Elevated plasma glucosylsphingosine in Gaucher disease: relation to phenotype, storage cell markers, and therapeutic response. Blood. 2011;118:e118–27. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-352971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rolfs A, Giese AK, Grittner U, Mascher D, Elstein D, Zimran A, et al. Glucosylsphingosine is a highly sensitive and specific biomarker for primary diagnostic and follow-up monitoring in Gaucher disease in a non-Jewish, Caucasian cohort of Gaucher disease patients. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Arkadir D, Dinur T, Revel-Vilk S, Becker Cohen M, Cozma C, Hovakimyan M, et al. Glucosylsphingosine is a reliable response biomarker in Gaucher disease. Am J Hematol. 2018;93:e140–2. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gieselmann V, Polten A, Kreysing J, von Figura K. Arylsulfatase A pseudodeficiency: loss of a polyadenylylation signal and N-glycosylation site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:9436–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Clarke LA, Wraith JE, Beck M, Kolodny EH, Pastores GM, Muenzer J, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of laronidase in the treatment of mucopolysaccharidosis I. Pediatrics. 2009;123:229–40. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Souillet G, Guffon N, Maire I, Pujol M, Taylor P, Sevin F, et al. Outcome of 27 patients with Hurler’s syndrome transplanted from either related or unrelated haematopoietic stem cell sources. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;31:1105–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fuller M, Brooks DA, Evangelista M, Hein LK, Hopwood JJ, Meikle PJ. Prediction of neuropathology in mucopolysaccharidosis I patients. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;84:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]