Abstract

The empirical evidence on the growth effects of import tariffs is sparse in the literature, notwithstanding strong views held by the public and politicians. Using an annual panel of macroeconomic data for 151 countries over 1963–2014, we find that tariff increases are associated with an economically and statistically sizeable and persistent decline in output growth. Thus, fears that the ongoing trade war may be costly for the world economy in terms of foregone output growth are justified.

Keywords: Output, VAR, Protectionism, Macroeconomic

1. Introduction

The economics profession is strongly in favor of free trade, but economists have not always done a great job convincing the public and politicians that trade should be free. The economists’ case for free trade is primarily based on: (a) theoretical models of comparative advantage; and (b) empirical evidence, mostly microeconomic, that suggest losses in economic efficiency and welfare from protectionism. But popular debates often focus on headline aggregate figures such as GDP, and what is largely missing from the literature is empirical macro analysis. Accordingly, in this paper we ask whether aggregate data are informative on the costs, if any, of raising tariffs.

The little literature we found does not fill us with confidence that the macroeconomic data will strengthen the professional economist's case. Despite the renewed interest on tariffs, recent studies have mostly concentrated on micro analyses for a handful of countries. The aggregate evidence by and large seems dated, and not particularly compelling; many of the empirical papers tended to find small macroeconomic effects. We were not deterred however, since most studies seem narrow. Bringing to bear more data, covering longer time periods and more countries, might allow us to obtain more precise estimates, and make better inferences about the size of macroeconomic effects. Thus we embarked on a data collection exercise, covering over 150 countries, and more than a half-century of data to tackle our basic question: does an increase in import tariffs boost the size and growth of the aggregate pie (GDP) or shrink it, and if so by how much?

Our efforts in this paper are thus focused on going back to basics—collecting data on tariffs across a wide country and time coverage, and estimating the impact on output using standard empirical-macro methodologies. Our objective is to paint a broad macroeconomic picture, based on traditional macro approaches and covering a large number of countries over a broad span of time, something that is missing in this discussion. As it turns out, our results suggest that using an extended database with substantial country and time coverage, does indeed deliver the goods.

Using aggregated annual data for 151 countries (34 advanced and 117 developing) over 1963–2014, we find that tariffs have economically- and statistically-significant adverse effects on output growth. The impact is persistent and increases with the magnitude of the tariff change. Our baseline econometric model suggests that a one standard deviation increase in the tariff rate (corresponding to a 3.6 percentage points) leads to about a 0.4% decline of output five years later. The estimated decline in output seems related to reduced efficiency in the use of labor across sectors, an appreciation of the real exchange rate which hampers competitiveness (and undercuts possible improvements in the trade balance), higher imported input costs which raise production costs, and intertemporal effects as anticipated tariffs bring forward consumption and output, only to see these macro variables collapse once the tariff is actually imposed. These different channels are fleshed out in a companion paper (Furceri et al., 2019); here, we focus mainly on the headline response of GDP growth.

Overall, our results provide a consistent first set of evidence on the macroeconomic costs from raising import tariffs. Moreover, the costs we identify are likely to be a lower bound on the costs of protectionist policies more generally, as the costs of nontariff barriers are likely higher than those of price-based restrictions.

2. Literature on output-effect of tariffs

“Major growth effects from trade policy, if they exist, must come from unconventional channels. Conventional trade theory DOES NOT justify claims of huge positive payoffs from free trade.”

Early debates about import protection can be traced back to the period when Britain imposed tariffs in response to the collapse of the gold standard during the Great Depression, with the idea that British unemployment could be reduced by imposing import controls (Cripps & Godley, 1978). Some studies supported this notion by showing that protectionist countries grew faster in the 19th century (Bairoch, 1972, O’Rourke, 2000). Eichengreen (1981), by introducing a process of adjustment and distinguishing between short-run versus long-run effects, showed that tariffs increase output and employment in the short run but could lead to a decline in production in the long run.

A host of other studies find either no or limited negative effects from tariffs (Krugman, 1982; Reitz and Slopek, 2005). Ostry and Rose (1992) show that there is no theoretical presumption about the effects of tariffs on output, with the impact depending on the timing and the expected duration of the tariff shock, the behavior of real wages and exchange rates, the values of the elasticities, and institutional factors (e.g. the exchange rate regime, degree of capital mobility). Consistent with their theoretical review, the authors find no significant effect of tariff changes on the real exchange rate, the real trade balance and real output (foreign or domestic) in their empirical work on five data sets and a non-structural VAR methodology.

The subsequent debates in the literature of the 1990s and 2000s focused on the growth impact of trade and trade policies, with the latter now comprising a host of trade restriction measures apart from tariffs. The connection between trade and growth was found to be broadly positive in these studies (Billmeier and Nannicini, 2013, Dollar, 1992, Feyrer, 2009, Sachs and Warner, 1995), though there has also been considerable debate on the results and the measurement of trade openness (Rodriguez and Rodrik, 2001, Temple, 2000). At the same time, the literature progressed to understand the impact of trade policies, using microeconomic data comprising different industries (see Amiti and Konings, 2007, Grossman and Rogoff, 1995, Topalova and Khandelwal, 2011).

With the renewed interest in tariffs nowadays, there has been a plethora of studies, but most of these have used a narrow range of disaggregated sectoral data and concentrated on a handful of countries, particularly the United States (Amiti, Redding, & Weinstein, 2019; Fajgelbaum, Goldberg, Kennedy, & Khandelwal, 2019). While these studies point toward welfare losses, the generality of the results is limited, given the sectoral focus and the limited coverage of countries. The question thus remains: what is the broad-based macro-level evidence related to the output-effect of tariffs?

3. First things first: data on tariffs

As simple as it sounds, given the straightforward measurability of tariffs compared to other trade barriers, there is no single database that includes tariffs across a broad set of countries for a large time period. Our first step was thus to collate reliable and harmonized (to the extent possible) tariff data using multiple sources. Our tariff data is based on product level data aggregated to the country level, with weights given by the import share of each product, all measured as a fraction of value. The main source is the reform dataset compiled by the Research Department of the IMF (Ostry, Prati, & Spilimbergo, 2009; Prati, Onorato, & Papageorgiou, 2013; Giuliano, Mishra, & Spilimbergo, 2013) which covers an unbalanced sample of 151 countries from 1964 to 2004. We extend the data to 2014 using tariff data from the World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) and World Development Indicators (WDI). Another valuable feature of this effort is that we do extensive data checks, to ensure that large tariff changes are not spurious, by cross-checking whether each jump is supported by country and policy reports.

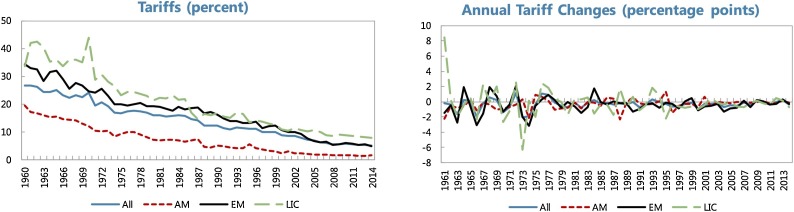

Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics, while Fig. 1 plots the evolution of tariffs across income groups. Advanced economies comprise 28 percent of the sample, emerging markets around 44 percent and low-income economies around 28 percent. As expected, there is more variation for both tariff levels and changes across low income countries and emerging markets, compared to advanced economies. Though the mean of our tariff series is negative and the time series plots in Fig. 1 show the general trend of tariffs declining over time, there is considerable variation; 40% of the sample consists of tariff rises (with mean of 1.7 ppt and standard deviation of 3.3), while 53% of observations consist of tariff falls (with mean of −1.8 ppt and standard deviation of 3.4). Appendix A reports the data sources and the list of countries used in our analysis.

Table 1.

Tariffs, descriptive statistics.

| Number of observations | Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tariffs | |||||

| All | 5042 | 11.2 | 13.8 | 0.0 | 161.6 |

| AM | 1427 | 5.7 | 7.5 | 0.0 | 99.2 |

| EM | 2161 | 12.5 | 11.6 | 0.0 | 91.4 |

| LIC | 1422 | 15.1 | 19.2 | 0.0 | 161.6 |

| Annual tariff changes | |||||

| All | 4702 | −0.3 | 3.6 | −52.0 | 41.2 |

| AM | 1392 | −0.3 | 2.2 | −43.6 | 16.1 |

| EM | 1960 | −0.4 | 3.5 | −24.3 | 27.6 |

| LIC | 1320 | −0.2 | 4.9 | −52.0 | 41.2 |

AM = advanced economies, EM = emerging economies, LIC = low income developing countries.

Fig. 1.

Tariffs and tariff changes across income groups.

The income groups are equally weighted averages of the tariffs of countries belonging to the particular income group.

4. The effect of tariffs on growth

We use two approaches to evaluate the effect of tariffs on output (growth): (i) some simple stylized-fact charts that show the evolution of growth following tariff hikes; (ii) more formal econometrics using a VAR methodology, so that we can trace the GDP (growth) response of tariffs over time (we explore alternative approaches in our 2019 paper). We then explore some of the possible underlying channels at work. The message from the findings in this section is loud and clear: tariffs have a sizeable negative effect on output growth, with detrimental effects persisting over years.

4.1. What do the data say?

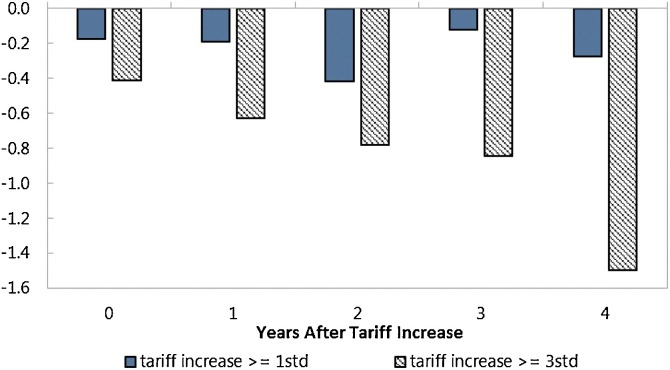

Given the extensive country and time coverage of the tariff data at our disposal, there is some value in just letting the data speak. Accordingly, Fig. 2 plots the evolution of output growth following substantial tariff increases. Following closely the approach of Ostry, Berg, and Kothari (2018), we compute residualized growth by taking residuals from regressions of annual real output growth on country- and time-fixed effects. We then take the average of the residualized growth measure across all countries with substantial tariff increases (greater than one/three standard deviation tariff increase(s), where one standard deviation is equivalent to a 3.6 percentage points tariff change).

Fig. 2.

Output growth (annual) after tariff hike (percent).

The findings suggest that tariffs have a detrimental effect on output, with the negative effect larger for higher tariff increases and persisting over time, at least over the next four years or so. The residualized growth tends to be in negative territory in all four years following an increase in protectionism. For example, after the second year, the residualized output growth is −0.4/−0.8 for one/three standard deviation(s) increases in tariffs, respectively. After four years, tariff increases are associated with an annual negative output growth of 1.5 percent when tariff increase is above three standard deviations.

4.2. Results from a VAR model

We now proceed to more formally estimate the output-effect of tariff changes using VAR (vector autoregressive) analysis. We look at tariff changes that are orthogonal to contemporaneous changes in economic activity, by employing a VAR analysis using a Cholesky decomposition with the following order to recover orthogonal shocks: the change in the log output (i.e., the growth rate), the change in tariff, the change in the log of the real effective exchange rate and the change in trade balance (in percent of GDP).

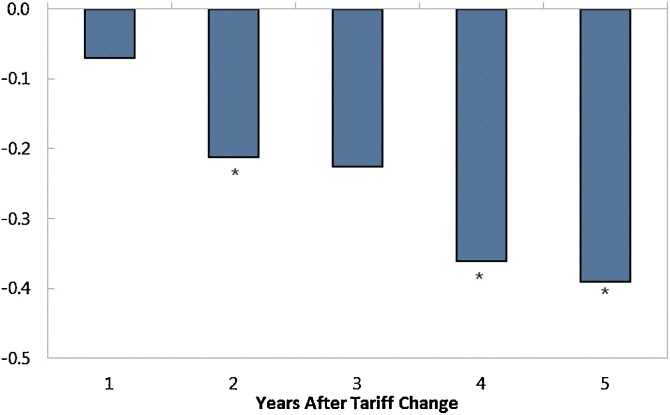

Fig. 3 shows the estimated dynamic response of output to a one-standard deviation rise in the tariff rate (around 3.6 percentage points). The results suggest that a one standard deviation tariff increase leads to a decline in output growth within the first year. While the effect is not initially statistically significant, output continues to decline in the next few years, and this effect becomes both economically and statistically significant within four years. Ultimately, a one standard deviation tariff increase leads to about a 0.4% decline in output five years later. In an effort to be conservative, we end our analysis at the five-year horizon: the longer-term output-effect of tariffs are actually higher than the estimated medium-term effects.

Fig. 3.

The effect of tariffs on output (%).

Note: The solid bar indicates the response of output to a one standard deviation increase in tariff; the asterisks denote that the results are within 90% confidence band.

These results are consistent with the stylized facts presented earlier: the output growth effect of tariff protectionism is non-negligible, persistent, and increases with the magnitude of the imposed tariffs. The results are robust to alternative orderings within the VAR model. In addition, they are robust to using local projections and instrumental variables approaches, as we show in Furceri et al. (2019). Specifically, using local projections, the results survive a host of robustness checks involving change of the key regressors, variations of the main sample, and inclusion of additional control variables (e.g. a crisis dummy, the nature of the political regime, M2 growth, and contemporaneous real exchange rate shocks).

4.3. The channels at work

Why does output fall after tariffs? Furceri et al. (2019) explore some plausible explanations. The wasteful effects of protectionism eventually lead to a substantial reduction in the efficiency with which labor is used, leading to a decline of about 0.9% of labor productivity after five years. Tariffs also lead to a small and marginally-significant increase in unemployment. Both of these effects plausibly lead to a reduction in output. In addition, using industry-level data, Furceri et al. (2019) show that the negative effect of tariffs seems to arise from an increase in the cost of (imported) inputs owing to tariffs. In our companion paper (Furceri et al., 2019), we also find that higher tariffs lead to an appreciation of the real exchange rate and the net effect on the trade balance is small and insignificant.

5. Conclusion: the trade war and output growth

Our results show that tariffs have persistent adverse effects on the size of the pie (GDP). How do our results map the macroeconomic effects of the current trade war? On one side, global trade, industrial production, and growth have either dropped or slowed, due to global trade tensions, tariffs, and trade policy uncertainty (IMF, 2019a, IMF, 2019b). In particular, global growth has slowed from around 3.8 percent in 2017 to 2.9 percent in 2019. On the other hand, economists—those who believe that tariffs have small macroeconomic effects—point out that the tariff effects have not been catastrophic. The trade war has not resulted in a 2008-type global crisis. And, according to IMF pre-COVID-19 projections, global growth was expected to gradually pick up in 2020 and 2021. Where is the persistent output-effect?

Policy responses, particularly accommodative monetary policy stance in key advanced and emerging markets, go a long way to solving this puzzle. The IMF estimates that global growth in 2019 and 2020 (their pre-COVID-19 projections) would have been 0.5 percentage point lower in each year without monetary stimulus. Without such stimulus, therefore, it seems likely that a global recession would have been in the realm of possibility in 2019. The risk of escalated trade tensions going forward, notwithstanding the China-US Phase 1 agreement, in an environment where macro policy space is more limited than before, also does not portend small global macroeconomic effects from tariffs going forward. This round of trade tensions has also brought to the fore the damaging effects of trade policy uncertainty on business confidence and investment decisions. There are also related to supply chain disruptions, which will cumulate over time and might intensify if trade peace is delayed. All this highlights the risk of more damaging first and second round effects going forward. These risks highlight the likelihood of large macroeconomic effects going forward, and should dispel the notion that tariff increases are costless.

Footnotes

This paper is part of a research project on macroeconomic policy in low-income countries supported by U.K.’s Department for International Development, and is related to earlier research by us, Furceri, Hannan, Ostry, and Rose (2019). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

Contributor Information

Davide Furceri, Email: dfurceri@imf.org.

Swarnali A. Hannan, Email: sahmed@imf.org.

Jonathan D. Ostry, Email: jostry@imf.org.

Andrew K. Rose, Email: bizaro@nus.edu.sg.

Appendix A.

Table A1, Table A2 provide the data sources and the list of the countries included in the analysis.

Table A1.

Data sources for country-level analysis.

| Indicator | Source |

|---|---|

| Total employment (persons, millions) | World Economic Outlook (WEO) |

| Unemployment rate (percent) | WEO and World Development Indicators from World Bank (WDI) |

| Gross Domestic Product in constant prices (national currency, billions) | WEO and WDI |

| Growth of Real GDP Exp. In Current Oct. Pub. (%) | WEO |

| Real effective exchange rate (2010=100) | Information Notice System (IMF) |

| Gini net mean of 100 | The Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID) |

| Tariff rates | Compiled by IMF Research Department (Prati, Onorato, and Papageorgiou 2013; Giuliano, Mishra, and Spilimbergo 2013). Underlying sources are the WITS, WDI, WTO, GATT, BTN (Brussels Customs Union database) |

| Trade balance as a share of GDP; Trade balance is computed using exports of goods and services, and imports of goods and services. Exports, imports and GDP are in constant prices (national currency, billions) | WEO and WDI |

| Crises | Leaven and Valencia (2010) |

| Wars, political regime | Polity database |

| Instruments for tariff | Author calculation using data from WDI and IMF Direction of Trade Statistics |

Table A2.

List of countries in country-level analysis.

| Albania | China | Hungary | Moldova | Singapore |

| Algeria | Colombia | Iceland | Mongolia | Slovak Republic |

| Angola | Comoros | India | Montenegro, Rep. of | Slovenia |

| Antigua and Barbuda | Congo, Republic of | Indonesia | Morocco | South Africa |

| Argentina | Costa Rica | Iran | Mozambique | Spain |

| Armenia | Croatia | Ireland | Myanmar | Sri Lanka |

| Australia | Cyprus | Israel | Namibia | St. Lucia |

| Austria | Czech Republic | Italy | Nepal | Swaziland |

| Azerbaijan | Cote d’Ivoire | Jamaica | Netherlands | Sweden |

| Bahrain | Denmark | Japan | New Zealand | Taiwan Province of China |

| Bangladesh | Dominica | Jordan | Nicaragua | Tanzania |

| Barbados | Dominican Republic | Kazakhstan | Niger | Thailand |

| Belarus | Ecuador | Kenya | Nigeria | Togo |

| Belgium | Egypt | Korea | Norway | Tonga |

| Belize | El Salvador | Kuwait | Oman | Trinidad and Tobago |

| Benin | Estonia | Kyrgyz Republic | Pakistan | Tunisia |

| Bolivia | Ethiopia | Lao P.D.R. | Panama | Turkey |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | Finland | Latvia | Papua New Guinea | Turkmenistan |

| Botswana | France | Lebanon | Paraguay | Uganda |

| Brazil | Gabon | Lithuania | Peru | Ukraine |

| Brunei Darussalam | Gambia, The | Luxembourg | Philippines | United Arab Emirates |

| Bulgaria | Germany | Macedonia, FYR | Poland | United Kingdom |

| Burkina Faso | Ghana | Madagascar | Portugal | United States |

| Burundi | Greece | Malawi | Qatar | Uruguay |

| Cabo Verde | Guatemala | Malaysia | Romania | Uzbekistan |

| Cambodia | Guinea | Mali | Russia | Vanuatu |

| Cameroon | Guinea-Bissau | Malta | Rwanda | Venezuela |

| Canada | Haiti | Mauritania | Saudi Arabia | Vietnam |

| Central African Republic | Honduras | Mauritius | Senegal | Yemen |

| Chad | Hong Kong SAR | Mexico | Sierra Leone | Zambia |

| Chile |

References

- Amiti M., Redding S.J., Weinstein D. The impact of the 2018 trade war on U.S. price and welfare. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2019;33(4):187–210. [Google Scholar]

- Amiti M., Konings J. Trade liberalization, intermediate inputs, and productivity: Evidence from Indonesia. American Economic Review. 2007;97(5):1611–1638. [Google Scholar]

- Bairoch P. Free trade and European economic development in the 19th century. European Economic Review. 1972;3:211–245. [Google Scholar]

- Billmeier A., Nannicini T. Assessing economic liberalization episodes: A synthetic control approach. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 2013;95(3):983–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Cripps W.M., Godley W. Control of imports as a means of full employment and the expansion of world trade: The UK's case. Cambridge Journal of Economics. 1978;2:327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Dollar D. Outward oriented developing economies really do grow more rapidly: Evidence from 95 LDCs, 1976–1985. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 1992;40:523–544. [Google Scholar]

- Eichengreen B.J. A dynamic model of tariffs, output and employment under flexible exchange rates. Journal of International Economics. 1981;11:341–359. [Google Scholar]

- Fajgelbaum P.D., Goldberg P.K., Kennedy P.J., Khandelwal A.K. 2019. The return to protectionism. NBER working paper 25638. [Google Scholar]

- Feyrer J. 2009. Distance, trade, and income – The 1967 to 1975 closing of the Suez canal as a natural experiment. NBER working paper no. 15557. [Google Scholar]

- Furceri D., Hannan S.A., Ostry J.D., Rose A.K. International Monetary Fund; 2019. Macroeconomic consequences of tariffs. IMF Working Paper No. 1909. Also posted as NBER Working Paper No. 25402 and CEPR Discussion Paper No. 13389. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano P., Mishra P., Spilimbergo A. Democracy and reforms: Evidence from a new dataset. AEJ: Macroeconomics. 2013;5(4):179–204. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman G.M., Rogoff K. Vol. III. Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.; Amsterdam: 1995. (Handbook of international economics). [Google Scholar]

- IMF . International Monetary Fund; 2019. 2019 external sector report: The dynamics of external adjustment. [Google Scholar]

- IMF . International Monetary Fund; 2019. World economic outlook. January 2020: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/01/20/weo-update-january2020. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman P. The macroeconomics of protection with a floating exchange rate. In: Brunner K., Meltzer A., editors. Vol. 16. 1982. pp. 141–182. (Monetary regimes and protectionism, Carnegie-Rochester series on public policy). [Google Scholar]

- Krugman P. “The One Minute Trade Policy Theorist,” the conscience of a liberal. The New York Times. 2013 https://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/02/05/wws-543-class-2-the-one-minute-trade-policy-theorist/ [Google Scholar]

- Leaven L., Valencia F. 2010. Resolution of banking crises: A new database. IMF working paper no. 10/44. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke K.H. Tariffs and growth in the late 19th century. Economic Journal. 2000;110:456–483. [Google Scholar]

- Ostry J.D., Berg A., Kothari S. International Monetary Fund; 2018. Growth-equity trade-offs in structural reforms. IMF working paper 18/5. [Google Scholar]

- Ostry J.D., Prati A., Spilimbergo A. 2009. Structural reforms and economic performance in advanced and developing countries. IMF occasional paper no. 268. [Google Scholar]

- Ostry J.D., Rose A.K. An empirical evaluation of the macroeconomic effects of tariffs. Journal of International Money and Finance. 1992;11:63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Prati A., Onorato M.G., Papageorgiou C. Which reforms work and under what institutional environment? Evidence from a new data set on structural reforms. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2013;95(3):946–968. [Google Scholar]

- Reitz S., Slopek U.D. Macroeconomic effects of tariffs: Insights from a new open economy macroeconomic model. Schweizerische Zeitschrift fur Volkswirtschaft und Statistik. 2005;141(2):285–311. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez F., Rodrik D. Trade policy and economic growth: A skeptics guide to the cross-national evidence. In: Bernanke B., Rogoff K., editors. NBER macroeconomics annual 2000. MIT Press, 2001; Cambridge, MA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs J.D., Warner A. Economic reform and the process of global integration. Brookings Papers in Economic Activity. 1995:1–118. [Google Scholar]

- Temple J. Growth regressions and what the textbooks don’t tell you. Bulletin of Economic Research. 2000;52:181–205. [Google Scholar]

- Topalova P., Khandelwal A. Trade liberalization and firm productivity: The case of India. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 2011;93(3):995–1009. [Google Scholar]