Abstract

Dynamin‐superfamily proteins (DSPs) are large self‐assembling mechanochemical GTPases that harness GTP hydrolysis to drive membrane remodeling events needed for many cellular processes. Mutation to alanine of a fully conserved lysine within the P‐loop of the DSP GTPase domain results in abrogation of GTPase activity. This mutant has been widely used in the context of several DSPs as a dominant‐negative to impair DSP‐dependent processes. However, the precise deficit of the P‐loop K to A mutation remains an open question. Here, we use biophysical, biochemical and structural approaches to characterize this mutant in the context of the endosomal DSP Vps1. We show that the Vps1 P‐loop K to A mutant binds nucleotide with an affinity similar to wild type but exhibits defects in the organization of the GTPase active site that explain the lack of hydrolysis. In cells, Vps1 and Dnm1 bearing the P‐loop K to A mutation are defective in disassembly. These mutants become trapped in assemblies at the typical site of action of the DSP. This work provides mechanistic insight into the widely‐used DSP P‐loop K to A mutation and the basis of its dominant‐negative effects in the cell.

1. INTRODUCTION

The dynamin‐superfamily proteins (DSPs) are a family of large GTPases that self‐assemble into helices, have low affinities for guanine nucleotides and function as mechanochemical enzymes that catalyze critical trafficking, membrane remodeling, and antiviral activities in cells.1, 2 To varying extents, members of the family share domain organizations which invariably include a large GTPase domain, a bundle signaling element (BSE) or closely‐related module that acts in intramolecular signaling, and a Stalk that is responsible for self‐assembly. Additional modules that may be found serve to fine‐tune the molecular properties of the DSP and may aid in recruitment, membrane tethering, or scission.1

The large GTPase domains of the DSPs interact with nucleotide in a manner similar to that seen in small GTPases such as p21 Ras.3, 4 GTP binding uses several motifs distributed throughout the domain to engage nucleotide.5 For example, residues within the P‐loop (also known as G1), bind and coordinate the phosphates of the nucleotide and residues in the G4 motif confer nucleotide specificity through a distinct pattern of hydrogen bonding to the guanosine base.3 One defining property of the DSPs is that their GTPase domains exhibit a basal rate of GTP hydrolysis that may be significantly enhanced by DSP self‐assembly.6 Structural work using minimal DSP GTPase‐BSE fusions as well as full‐length DSPs demonstrated that this stimulation is a consequence of GTPase‐GTPase dimerization within the assembled DSP, which serves to orient the catalytic machinery into an optimal configuration for hydrolysis.7, 8, 9, 10

Efficient GTP hydrolysis requires neutralization of a negative charge that develops between the β‐ and γ‐phosphates in the transition state.11 The crystal structure of the human dynamin‐1 GTPase‐BSE fusion in complex with the transition state mimic GDP.AlF4 − showed that a bound magnesium ion, a charge‐compensating sodium ion, and the ε‐amino group of the absolutely conserved P‐loop lysine K44 act in concert to satisfy this condition.7 Perturbation of any of these components abrogates GTP hydrolysis in vitro. Based on its critical catalytic role, mutation of the P‐loop lysine to alanine has repeatedly been used as a tool to examine and disrupt the biological activities of various DSPs. For example, the K44A mutation in human dynamin‐1 blocks formation of endocytic coated vesicles,12, 13 K41ADnm1 produces gross alterations in the mitochondrial network,14 and K42AVps1 results in mis‐trafficking of carboxypeptidase Y.15

To date, the effects of the P‐loop K to A mutation in DSPs have been predicted from structural and biochemical analyses of p21 Ras.12, 16 Mutation of the Ras P‐loop K to N reduces affinities for GDP and GTP by 65‐ and 180‐fold respectively, from 20 nm to 1.3 μM and from 10 nM to 1.8 μM.17 Based on this work, mutation of the DSP P‐loop K has been suggested to generate protein that is both binding‐deficient and catalytically inactive.12 In support of this, increasing the GTP concentration from 100 to >300 μM resulted in some GTP hydrolysis for K41Adynamin,13 which was interpreted in terms of a lowered affinity for GTP, a lowered k cat, or both. GTP binding to K41ADnm1 is also impaired compared to wild type Dnm1, as assessed by UV cross‐linking.18 This observation was again attributed to a lowered binding affinity.

Small GTPases and dynamin family members, however, differ with respect to nucleotide affinities, with Ras binding GTP and GDP are in the picomolar range,19 and DSPs binding in a low micromolar range with free nucleotide exchange that does not require exchange factors.20, 21

Here, we performed a structural and functional study of the P‐loop K to A mutation, using minimal DSP GTPase‐BSE fusions and full‐length proteins. We use the fungal endosomal DSP Vps1 as our primary model. Surprisingly, the Vps1 GTPase‐BSE K to A mutant interacts with nucleotides and nucleotide analogs with an affinity similar to that of the wild type. Vps1 GTPase‐BSE is impaired in dimerization in the presence of the transition state mimic GDP.AlFx. We use crystallography to show that the P‐loop K to A mutant of Vps1 GTPase‐BSE clearly binds to the non‐hydrolyzable GTP analog GMPPCP but has deficits in the organization of critical waters within the active site. In the context of full‐length Vps1 or the mitochondrial division DSP Dnm1, the K to A mutants assemble at their corresponding cellular locations in vivo, while GTPase‐BSE constructs alone are cytosolic. We therefore conclude that the P‐loop K to A mutants are as nucleotide binding competent as their wild type counterparts and that their effects are due to impaired hydrolysis. In cells, the P‐loop K to A mutant DSPs manifest their phenotypes only in the contexts of full‐length DSPs, by preventing disassembly and recycling of the DSP.

2. RESULTS

2.1. Biochemical and biophysical characterization of the Vps1 GTPase‐BSE construct

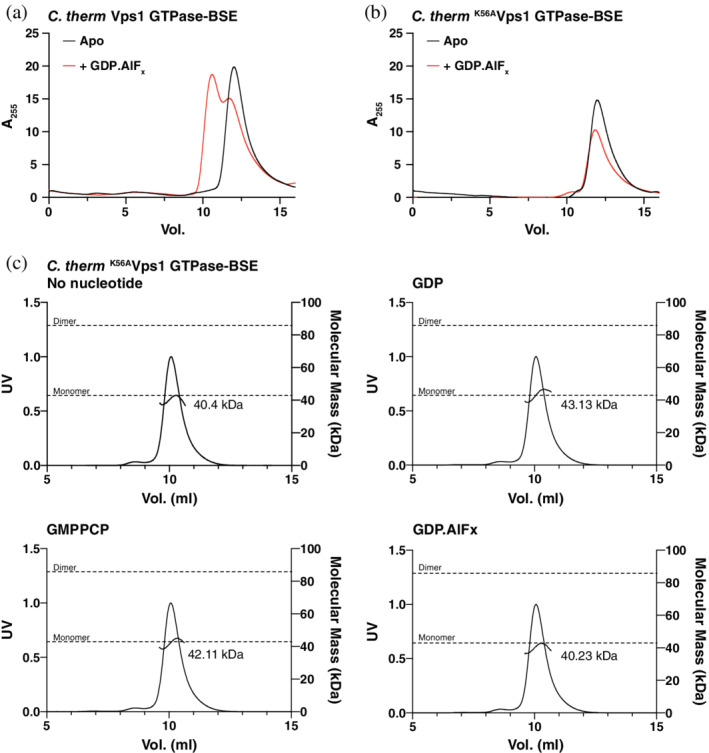

The minimal DSP GTPase‐BSE fusion construct has previously been used for structural and functional characterization of several DSPs.1 The dynamin‐1 or the Vps1 GTPase‐BSE constructs homodimerize in the presence of the transition state mimic GDP.AlFx but remain monomeric in the absence of nucleotide, or in the presence of GDP or the non‐hydrolyzable GTP analogs GMPPCP or GTPγS.7, 15 We initially assessed dimerization of Chaetomium thermophilum (C. therm) K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE by monitoring elution using analytical size exclusion chromatography (SEC). While the rate of C. therm Vps1 GTPase‐BSE migration through the column increased in the presence of GDP.AlFx, indicating dimerization (Figure 1a), the rate of the K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE mutant did not (Figure 1b). Neither GTP nor GDP, nor the nonhydrolyzable analog GMPPCP, altered the rate of migration of the mutant, which was consistent with wild type Vps1 GTPase‐BSE in the absence of nucleotide (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE does not dimerize in the presence of GDP.AlFx. (a,b) Analytical size exclusion chromatography of (a) C. therm Vps1 GTPase‐BSE and (b) C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE in the absence or presence of GDP.AlFx. The elution volume decreased in the presence of GDP.AlFx for wild type Vps1 GTPase‐BSE, but not K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE, consistent with dimerization. (c) Determination of the absolute molecular mass of C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE in the absence or presence of various nucleotides or nucleotide analogs by SEC‐MALS. The theoretical molecular masses of monomers and dimers are shown as dotted grey lines. The measured molecular masses in each case are shown on the trace. No changes in molecular mass were observed

We next determined the absolute molecular mass of C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE in the absence and presence of several nucleotides and nucleotide analogs using SEC coupled with multi‐angle light scattering (SEC‐MALS). Previously, Vps1 GTPase‐BSE was measured to have a molar mass of 40,280 Da in the absence of nucleotide and 78,530 Da in the presence of GDP.AlFx.15 By contrast, the molar mass of K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE was 40,400 Da in the absence of nucleotide and 40,230 Da in the presence of GDP.AlFx (Figure 1c). Results with GMPPCP and GDP were similar (42,110 and 43,130 Da, respectively).

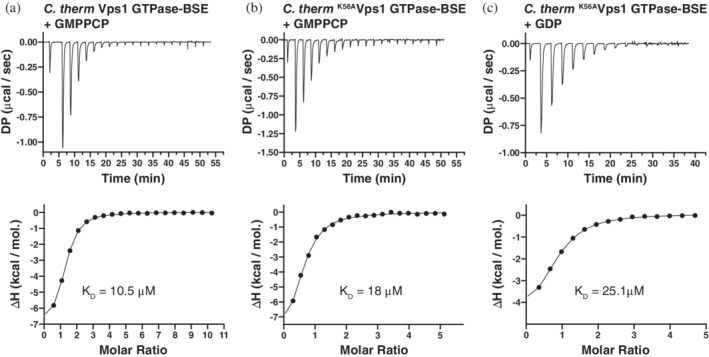

We performed isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to determine whether C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE interacted with nucleotide and nucleotide analogs. C. therm Vps1 GTPase‐BSE interacted with GMPPCP with a dissociation constant of 10.5 μM (Figure 2a). Surprisingly, a similar affinity was observed for the interaction between C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE and GMPPCP (18 μM, Figure 2b). GDP also interacted with K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE, with an affinity 25.1 μM (Figure 2c). K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE binding to GTP was more variable but had a mean K D of 12.6 μM (Table S1). Therefore, in the case of Vps1, the P‐loop K to A mutant is not impaired in nucleotide binding. A similar result was reported for an oligomerization‐defective mutant of the antiviral DSP MxA (M572D), where the affinities of GTPγS for M572DMxA and K83A,M572DMxA are 15 and 39 μM respectively,22 a small decrease in binding affinity on mutation of the P‐loop lysine.

Figure 2.

C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE binds to GMPPCP with a similar affinity as wild type Vps1 GTPase‐BSE, as determined by ITC. Binding of GMPPCP to C. therm Vps1 (a) GTPase‐BSE and (b) C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE. (c) Binding of GDP to C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE. In each case, upper panels show the thermograms for each titration. DP—differential power. Lower panels show the normalized binding isotherms obtained from the integrated peaks from the thermograms (filled circles), together with the fit obtained from a single site binding model (lines). Mean measured K D values are shown on the isotherms

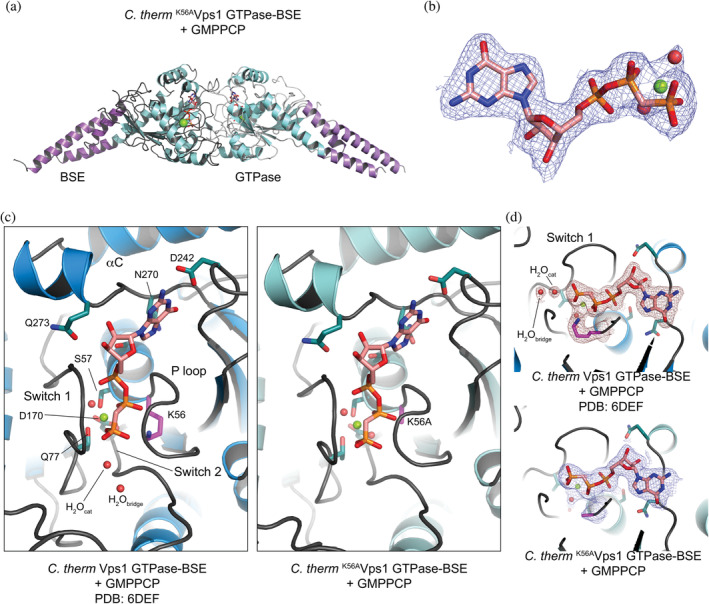

2.2. The crystal structure of K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE in complex with GMPPCP

To confirm that nucleotide interacts with K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE, and to determine the structural basis for the defect in GTP hydrolysis, we solved the crystal structure of C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE in complex with GMPPCP to a minimum resolution of 2.47 Å. K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE crystallized with two dimers in the asymmetric unit, with the same cell and packing as that observed for crystals of Vps1 GTPase‐BSE bound to GMPPCP.15 Each monomer was bound to a molecule of GMPPCP. The dimers were formed by a large GTPase‐GTPase interface, which is similar to what was observed with Vps1 GTPase‐BSE bound to GMPPCP, as well as a homologous construct of dynamin‐1 GTPase‐BSE bound to GMPPCP.10, 15 In the case of the K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE crystals, the GTPase‐GTPase interfaces were of size 2,710 Å2 and the BSEs were in the open, or extended, conformation, pointing away from the bodies of their GTPase domains (Figure 3a,b).

Figure 3.

The crystal structure of C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE in complex with GMPPCP. (a) Ribbon diagram of a C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE dimer, in complex with GMPPCP. The BSEs are shown in lighter and darker purples and the GTPase domains are shown in shades of mint. GMPPCP is shown in stick representation, with the bound magnesium ion as a sphere. (b) 2mFobs‐DFcalc density map of one of the GMPPCP molecules in the asymmetric unit, contoured at 1σ. The GMPPCP is shown in stick representation and the bound magnesium with its associated waters are shown as spheres. (c) Comparison of the nucleotide binding pocket of Vps1 GTPase‐BSE bound to GMPPCP (PDB 6DEF) and K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE bound to GMPPCP. For wild type Vps1 GTPase‐BSE, the GTPase domain is shown in blue. For K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE, the same color scheme is used as in A. (d) 2mFobs‐DFcalc density maps observed around K56 in Vps1 GTPase‐BSE (PDB 6DEF, top) and K56A in K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE (bottom). Maps were contoured at 1σ. Note the absence of H2Ocat and H2Obridge in the K56A mutant. H2Obridge was not visible in any of the molecules in the asymmetric unit, whereas weak density for H2Ocat could be built as a water in two of the K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE molecules

The positioning and pose of the GMPPCP in the nucleotide binding pocket were similar to that previously observed in the crystals of Vps1 GTPase‐BSE bound to GMPPCP (Figure 3c). However, there are some significant differences, which provide key insight into the mechanistic deficit of the K56A mutants. In the Vps1 GTPase‐BSE structures, we observed clear density for both the catalytic and bridging waters (H2Ocat, H2Obridge) in each of the four molecules in the asymmetric unit (Figure 3c,d).15 H2Ocat is the nucleophile for the hydrolysis7 and its position is stabilized by H2Obridge, which is, in turn, stabilized by, at a minimum, the carbonyl of G173. While we observed weak density for H2Ocat in two of the four K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE molecules in the asymmetric unit, we observed no H2Obridge in any of the active sites. Hence, loss of the lysine side chain impairs the organization of the key waters in the active site.

In the structure of the dynamin‐1 GTPase‐BSE bound to GDP.AlF4 −, H2Obridge is also stabilized by the side chain of Q40 (Q52 in C. therm Vps1).7 In the GMPPCP‐bound structures of C. therm Vps1 GTPase‐BSE and C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE, however, this side chain adopts a different conformation, with the Cδ amine contacting the γ‐phosphate of GMPPCP. The reason for this is the presence of the GMPPCP: as a result of the methylene between the β‐ and γ‐phosphates, instead of the oxygen at this position in GTP, a charge‐compensating cation cannot be stabilized because a direct contact between the oxygen and the cation is required for stabilization. Consequently, none of the GMPPCP‐bound GTPase‐BSE structures contain a charge‐compensating ion in the binding site. When the charge‐compensating ion is present, as observed in structures of dynamin‐1 GTPase‐BSE or Vps1 GTPase‐BSE bound to the transition‐state mimic GDP.AlF4 −, it is coordinated by multiple residues at the base of the P‐loop and in Switch 1, as well as the nucleotide itself. In particular, it coordinates the P‐loop serine (S40 in dynamin‐1; S53 in C. therm Vps1). Once S53 is coordinated, Q52 will be forced into a conformation competent to coordinate H2Obridge. K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE therefore lacks both means of stabilizing H2Obridge: the presence of K56 and the conformation of Q52. Hence H2Ocat cannot mount a nucleophilic attack.

We also note that in the Vps1 GTPase‐BSE GMPPCP‐bound structure, the conformation of D214 in the dimer partner, which typically reaches across the interface to contact Q52, is well ordered in each of the monomers in the asymmetric unit. D214 is part of the trans‐stabilizing loop.1, 7 In dynamin‐1, mutation of the D214 equivalent (D180) blocks assembly‐stimulated GTPase activity,7 for which dimerization is required. In K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE, D214 appears somewhat less‐well ordered, as does, to a lesser extent, N217 in the same trans‐stabilizing loop. This may be an additional component of the impaired dimerization seen in K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE in vitro.

It is known that the P‐loop K to A mutant, in the context of dynamin‐1 (K44A), is incompetent in GTP hydrolysis.23 Mutation of the lysine to alanine results in a loss of positive charge in the proximity of the β‐ and γ‐phosphates. Magnesium and sodium ions, together with the lysine side chain, position the β‐ and γ‐phosphates for optimal nucleophilic attack by the catalytic water, H2Ocat. In the GMPPCP‐bound K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE structure, we observed weak density centered on the position where the ε‐amino group of the P‐loop lysine is located in the Vps1 GTPase‐BSE structure in one of the 4 molecules in the asymmetric unit, which we interpreted as a poorly‐ordered water. A function of the P‐loop is to keep the phosphates in the GTP in an extended conformation to permit hydrolysis.24 Molecular dynamics simulations show that, in water, Mg2+‐ATP or Mg2+‐GTP are held in an equivalent extended conformation by K+, Na+ or NH4 + ions. In an active site, the ε‐amino group of the P‐loop lysine is in the same position as one of the ions (the other is either an ion or an arginine/lysine).24 We therefore hypothesized that, if the weak density is an ion, the effects of the loss of the positive charge contributed by the lysine may be counteracted by increasing the concentration of cations available to the active site. We therefore determined the kinetics of GTP hydrolysis by K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE in comparison to wild type Vps1 GTPase‐BSE at different concentrations of sodium chloride. We used the coupled GTPase assay wherein GTP is continuously regenerated.25 At a GTP concentration of 1 mM, 150 mM salt and pH 7.4, wild type Vps1 GTPase‐BSE hydrolyzed GTP with a basal rate of 0.8 min−1, similar to that recently reported for Vps1 GTPase‐BSE and measured using a colorimetric assay (1.1 min−1).15 K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE did not have any measurable activity under these conditions. No changes in the rate of basal GTPase activity were observed when the salt concentration was altered to 50 or 500 mM NaCl for wild‐type Vps1 GTPase‐BSE (0.8 min−1 in each case). However, no hydrolysis was detectable under any condition for K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE. Similarly, varying the reaction pH from 7.0 to 7.8 resulted in activities of 0.8–1.3 min−1 for the wild type protein, with no detectable hydrolysis for the K56A mutant (Table S2). As the continuous assay has limited sensitivity at low rates of GTP hydrolysis, we also used the colorimetric GTPase assay. No hydrolysis was detected by K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE at a wide range of GTP concentrations (data not shown).

Taken together, these data demonstrate that, while the K56A mutant is capable of binding nucleotides with approximately the same affinity as wild type protein, dimerization in the presence of the transition state analog GDP.AlFx is abrogated and GTPase activity is abolished under all conditions tested. The defect of the P‐loop K to A mutation, at least in Vps1, is therefore a hydrolysis defect caused by loss of co‐ordination of key waters, rather than a consequence of reduced binding.

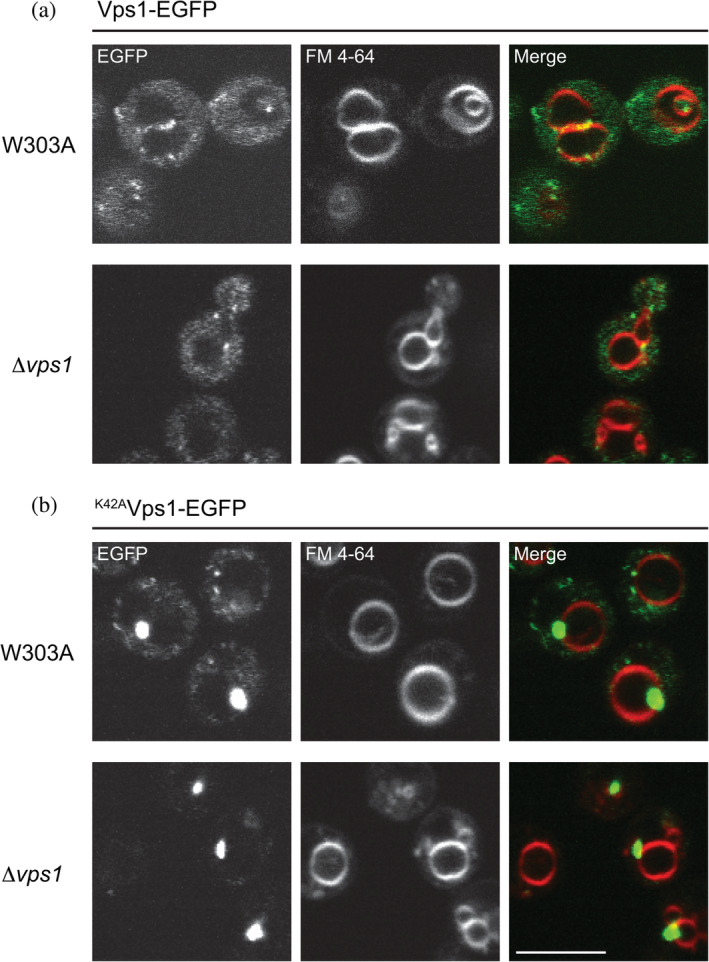

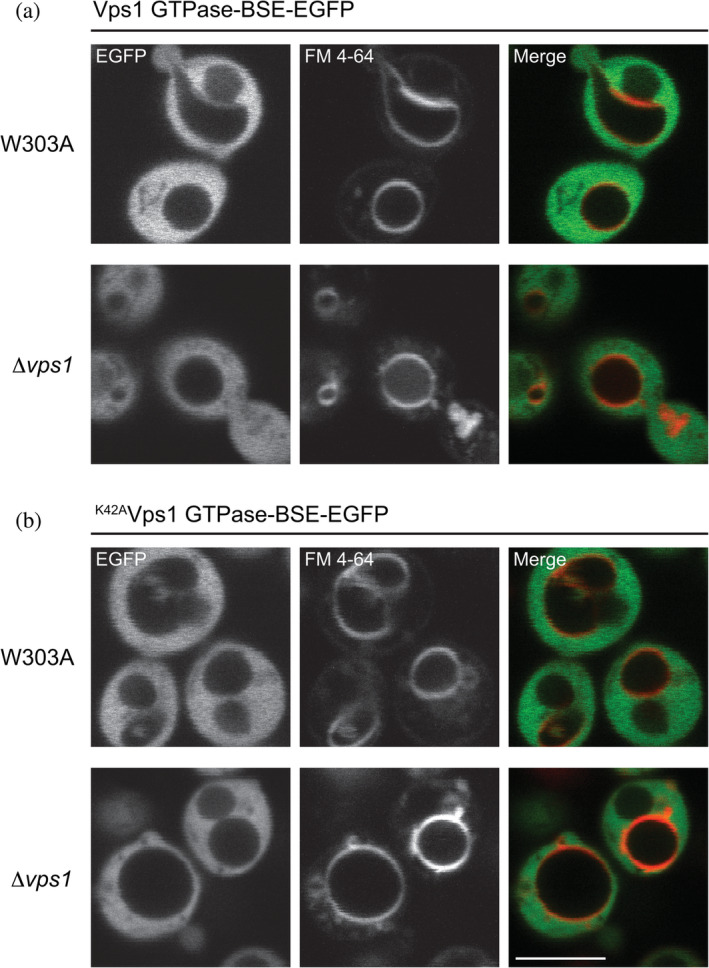

2.3. The DSP P‐loop K to A mutant is dominant‐negative only in the context of full‐length DSPs

We previously reported that wild type Vps1, C‐terminally tagged with EGFP, localized to the perivacuolar endosomal compartment in S cerevisiae (S cer.) (Figure 4a).15 The same punctate distribution was observed in the absence of endogenous Vps1 (Figure 4a). In wild type (W303A: W303 MAT a) cells or Δvps1 cells, S. cer K42AVps1 (the equivalent mutant to C. therm K56AVps1) localized to few perivacuolar puncta, which were particularly intense (Figure 4b). In cells lacking endogenous Vps1, no residual cytosolic K42AVps1 component was observed, suggesting complete incorporation of K42AVps1 into the puncta. Similar results were observed when C. therm Vps1 or C. therm K56AVps1 were expressed in wild type cells (Figure S2). When we overexpressed untagged S cer. K42AVps1, using the GAL1 promoter, in wild type cells also expressing Vps1 tagged with EGFP, extended filaments were formed (Figure S3). Furthermore, we note that overexpression of K42AVps1 resulted in induction of a dominant‐negative phenotype and appearance of the Class F vacuolar morphology, characterized by a single large spherical vacuolar compartment, often surrounded by additional small vacuolar fragments.26

Figure 4.

S cer. K42AVps1 assembles into few, intense puncta on the perivacuolar compartment in wild type (W303A) and Δvps1 cells. (a) When expressed in W303A or Δvps1 cells, S cer. Vps1‐EGFP distributed between the cytosol and dynamic perivacuolar puncta. (b) S cer. K42AVps1‐EGFP concentrated to few intense puncta at the perivacuolar compartment. Note that in Δvps1 cells, very little residual cytosolic staining was observed. Vacuoles were stained with FM 4–64. Scale bar—5 μm

To determine whether the P‐loop K to A mutant has to be present in the context of full‐length protein for its cellular effects, we overexpressed both wild type and K42AVps1 GTPase‐BSE in wild type and Δvps1 cells using the doxycycline‐controlled transactivator, which consists of a fusion of the tetracycline repressor with the C‐terminal activation domain of VP16 from the herpes simplex virus.27 In the presence of endogenous Vps1, overexpression of Vps1 GTPase‐BSE or K42AVps1 GTPase‐BSE resulted in a smooth, cytosolic distribution. No puncta were formed, and, in addition, the vacuolar morphology was not altered (Figure 5a). Overexpression of either Vps1 GTPase‐BSE or K42AVps1 GTPase‐BSE in Δvps1 cells also did not result in puncta formation or restore the Class F vacuolar phenotype to its wild‐type morphology (Figure 5b). Hence, the mutant must be present in the context of full‐length Vps1 for function.

Figure 5.

Overexpressed S cer. Vps1 GTPase‐BSE or S cer. K42AVps1 GTPase‐BSE is cytosolic. (a) S cer. Vps1 GTPase‐BSE‐EGFP expressed in W303A or Δvps1 cells was fully cytosolic. Note the Class F vacuolar phenotype in the Δvps1 cells. (b) S cer. K42AVps1 GTPase‐BSE‐EGFP expressed in W303A or Δvps1 cells was similarly cytosolic, in both W303A and Δvps1 cells. Scale bar—5 μm

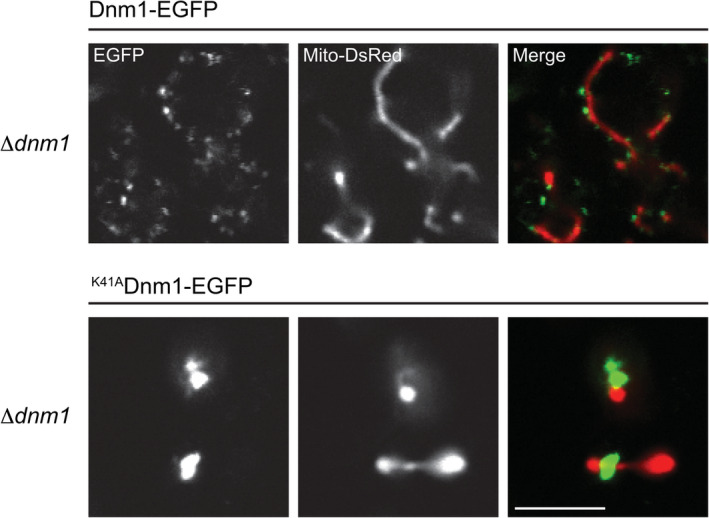

We next asked whether the intense puncta formed by K42AVps1 were assemblies or nonspecific aggregates. These puncta were formed at the site of action for Vps1 and hence likely represent assemblies. To further address this, we introduced the P‐loop K to A mutation into the DSP Dnm1, which is required for mitochondrial fission28 and, therefore, has a different cellular localization. We introduced GFP‐tagged Dnm1, with or without the K mutation (K41ADnm1), into Δdnm1 cells, where the mitochondrial network had been labeled with DsRed Express. In the absence of Dnm1, the normal reticular mitochondrial network collapses into an extensively netted network, due to continued mitochondrial fusion in the absence of fission (Figure S4). Expression of Dnm1‐EGFP in Δdnm1 cells restored the typical reticular mitochondrial morphology. Dnm1 formed puncta associated with the mitochondrial network, as has been reported previously (Figure 6).14, 18 By contrast, expression of K41ADnm1‐EGFP did not restore a reticular mitochondrial network and the mutant formed intense puncta. These were localized to the netted mitochondrial network (Figure 6). K42AVps1‐EGFP puncta, on the other hand, were not associated with the mitochondrial network (Figure S5). Therefore, the localization of the intense puncta formed by the P‐loop K to A mutations is determined by the host DSP and are therefore not simply cytosolic aggregates.

Figure 6.

S cer. K41ADnm1 assembles into few, intense puncta on the mitochondrial network in Δdnm1 cells. Δdnm1 cells were labeled with mitochondrial matrix‐targeted DsRed (Mito‐DsRed). S cer. Dnm1‐EGFP expressed in Δdnm1 cells restored the mitochondrial reticular morphology observed in W303A cells and largely localized to small puncta on the surface of the mitochondrial network. S cer. K41Dnm1‐EGFP failed to rescue the collapsed, netted, mitochondrial network and localized to intense puncta on the surface of the mitochondrial network. Scale bar—5 μm

3. DISCUSSION

The DSP P‐loop lysine to alanine mutation has repeatedly and widely been used in DSP studies to specifically and selectively disrupt the biological process in which the DSP is involved. However, the precise nature of the molecular defect of this mutant remained an open question, with suggestions that it may be both binding and/or hydrolysis‐deficient.2, 12

We found that, in the context of the endosomal DSP Vps1, the K56A mutant bound to nucleotides with similar affinities to that of the wild type protein. These affinities were slightly higher than, but comparable to, the affinities previously estimated from KM values for the dynamin GTPase domain21, 29 (GTP: 35–65 μM, dependent on temperature). They were also comparable to the affinities measured for DRP130 (GDP: 10 μM; GTPγS: 23 μM) and an assembly‐defective MxA22 mutant (GTPγS, MxA: 15 μM; GTPγS K83AMxA: 39 μM) by isothermal titration calorimetry. We confirmed the nucleotide binding by determination of the crystal structure of K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE bound to the non‐hydrolyzable GTP analog GMPPCP. In the structure, the nucleotide analog engages the binding site with the same pose as in the wild type protein.

The conserved P‐loop lysine, along with the bound magnesium cofactor and charge‐compensating ion, functions to counteract the developing negative charge in the transition state. In the P‐loop K to A mutant, charge‐compensation is impaired and the organization of H2Ocat and H2Obridge are altered from their ideal geometry. These changes disrupt productive nucleophilic attack, rendering the K to A mutant catalytically inactive.

The P‐loop K to A mutant of Vps1 GTPase‐BSE did not dimerize in solution in the presence of GDP.AlFx or any other nucleotide or nucleotide analog. However, the crystal structure of K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE in the presence of GMPPCP did have the GTPase‐GTPase interface. In the case of dynamin‐1 GTPase‐BSE, dimer formation in the presence of GDP.AlFx was shown to have a dissociation constant of 8.4 μM,10 with dimerization in the presence of GMPPCP being weaker to the extent of not being measurable. As the GTPase‐GTPase interface was observed in the presence of GMPPCP in the crystals of both dynamin‐1 GTPase‐BSE and Vps1 GTPase‐BSE, it is possible that the crystallization environment with its enhanced protein concentrations generated the interface. However, K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE did not form dimers in the presence of GDP.AlFx by SEC‐MALS even though the starting protein concentration was in excess of 90 μM, an approximately 10‐fold excess over the K D, assuming that Vps1 GTPase‐BSE has a similar dimerization constant to dynamin‐1 GTPase‐BSE. Hence, the K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE is apparently defective in dimerization, which may be a consequence of the increased flexibility we observed within the trans‐stabilizing loop.

Similar reasoning may also apply to expression or overexpression of Vps1 GTPase‐BSE in cells: local concentrations of GTPase‐BSE may not reach levels in excess of the dimerization dissociation constant that will permit stabilization and persistence of dimers. As a result, the GTPase‐BSE constructs appear diffuse and cytosolic. When the mutant is presented in the context of full‐length protein, however, the local concentration of the GTPase‐BSE is presumably sufficient to form dimers. As these cannot hydrolyze the GTP in the presence of the P‐loop K to A mutant, disassembly cannot occur, and the host DSP becomes trapped. Hence the in vivo effect of the mutant is a DSP recycling deficiency.

Cryo‐EM helical reconstructions have been performed for both dynamin‐1 ΔPRD, in the presence of GMPPCP, and for K44Adynamin‐1.10, 23, 31 The most recent reconstruction of GMPPCP‐bound dynamin‐1 ΔPRD demonstrated that the GTPase‐GTPase interface indeed forms and connects dynamin protomers from adjacent rungs in the assembled helix, indicating that the local GTPase concentration may indeed result in formation of this interface. The reconstruction of K44Adynamin‐1 is of an intermediate resolution so it is unclear whether nucleotide is incorporated. However, because the GMPPCP‐bound dynamin‐1 GTPase‐BSE, with its GTPase‐GTPase interface, could be docked into the helical density, the GTPase‐GTPase interface is likely present in this reconstruction. Early work with Dynamin assemblies reported that disassembly follows GTP hydrolysis.2, 32 A block in hydrolysis, as observed with the P‐loop K to A mutant, may therefore preclude disassembly and recycling and hence obstruct the underlying biological process. Indeed, the simultaneous presence of wild type Vps1 and K42AVps1 in cells permits the presence of some cytosolic Vps1, suggesting partial disassembly of Vps1 continues. Disassembly therefore depends on hydrolysis and the cellular effects of the P‐loop K to A mutants are a consequence of defective hydrolysis blocking disassembly.

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1. Cloning

Plasmids used in the course of this work are detailed in Table S3. In the C. therm VPS1 GTPase‐BSE constructs, residues 355–668 of the VPS1 coding sequence were replaced with an Ala–Gly–Ala–Gly–Ala linker. The corresponding S cer. VPS1 GTPase‐BSE constructs replaced residues 363–675 of the VPS1 CDS, again with the Ala–Gly–Ala–Gly–Ala linker. Mutants were invariably generated by splicing by overlap extension (SOE), followed by Gibson assembly. The DNM1 coding sequence, with a 265‐nucleotide upstream sequence, was amplified from genomic DNA isolated from W303A/α diploids using the Yeast DNA Extraction kit (Thermo Scientific). DNM1 and the various VPS1 GTPase‐BSE constructs were fused to a cassette consisting of the coding sequence of EGFP and a terminator from S cer. VPS1 (300 nucleotides) by SOE.

4.2. Protein expression and purification

C. therm Vps1 GTPase‐BSE and C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE were expressed in BL21 cells, overnight at 21°C, by IPTG induction (51. 4 μM final concentration). Cells were harvested, washed and resuspended in TN (20 mM TRIS/Cl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1.93 mM β‐mercaptoethanol) and lysed by homogenization with an Emulsiflex‐C3 (Avestin). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 142,000g in the T647.5 rotor for 45 min at 4°C. His‐tagged proteins were harvested in batch, by incubation with Ni‐IDA beads (Machery‐Nagel). After washing, the beads were packed into a column and fusion proteins were eluted with an imidazole gradient, to 250 mM, in TN. Vps1 GTPase‐BSE was then dialyzed against TN. K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE was dialyzed against HN (TN with 20 mM HEPES/NaOH pH 7.4 in place of TRIS/Cl). The N‐terminal His6 tags were removed by digestion with PreScission protease (GE Healthcare), at a final concentration of ~1 Unit per ml, in a total volume of ~50 ml, at room temperature for 3 hr. Both proteins were further purified by anion exchange and size exclusion chromatography, the latter using a Superdex 200 16/60 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in HN with 5–25 mM HEPES/NaOH pH 7.4. Proteins were concentrated and flash‐frozen in liquid nitrogen until use.

4.3. Crystallization

C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE (60 μM) was incubated with 1 mM β,γ‐methyleneguanosine 5′‐triphosphate (GMPPCP, Sigma Aldrich) for 1 h at room temperature in 5 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1.93 mM β‐mercaptoethanol. Crystals were grown by sitting drop vapor diffusion at room temperature, by equilibration of droplets of 0.8 μl, containing 20–30 μM protein and 0.5 mM GMPPCP, against a reservoir of 44 μl containing 91 mM HEPES pH 8.1, 16.7% PEG 3,350, 182 mM sodium acetate and 2‐propanol to a final concentration of 3%. Crystals were harvested after 7 months. Crystals were cryo‐protected by sequential transfer through solutions of the crystallization condition supplemented with 0.5 mM GMPPCP and increasing concentrations of glycerol to a final concentration of 15%. Cryo‐protected crystals were mounted and flash‐cooled in liquid nitrogen for storage until data collection.

4.4. Crystallographic data collection, structure determination and refinement

Reflection data for C. therm K56AGTPase‐BSE in complex with GMPPCP were collected at 100 K at ID‐22 at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory) at a wavelength of 0.91299 Å, using an Eiger detector. Crystals are monoclinic and belong to spacegroup P21, with cell axes a = 81.87, b = 119.03, c = 85.58 Å, β = 100.95°. Several datasets were collected, which were indexed and integrated using iMOSFLM.33 Dataset clustering and pruning was performed using BLEND from the CCP4 suite of crystallographic software. The cluster retained for scaling was identified by assessing the merging statistics of the different clusters. The data were scaled using AIMLESS.34 Data collection statistics are shown in Table S4.

The K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE structure was solved by molecular replacement, using Phaser,35 part of the Phenix suite of crystallographic software.36 The structure of C. therm Vps1 GTPase‐BSE in complex with GMPPCP (PDB 6DEF)15 was used as a search model and four copies were placed in the asymmetric unit, forming two dimers.

The model was iteratively refined with Refmac5,37 using TLS, with one TLS group per protein chain in the asymmetric unit, and restrained coordinate and individual B factor refinement. Corrections were made using COOT.38 The model was improved using PDB_REDO39 prior to deposition. Refinement statistics and final model geometries are shown in Table S5. Structure images were made using Pymol.40

4.5. GTPase assays

Continuous GTPase assays25 were performed as described.15 Reactions contained a final GTP concentration of 1 mM. Reactions contained 142.5 mM NaCl, 7.5 mM KCl and 5 mM MgCl2 and were conducted at pH 7.4, generated using 25 mM each of HEPES and PIPES. To alter the salt concentration, the final concentration of NaCl was adjusted: 7.5 mM KCl was present in each case.

The colorimetric GTPase assay was performed using the malachite green assay kit (Echelon Biosciences) as described.15 Reactions contained 142.5 mM NaCl, 7.5 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2 and were performed at pH 7.0. After a 10 min preincubation at 37°C, reactions were started by addition of GTP to various final concentrations.

4.6. Analytical size‐exclusion chromatography

Vps1 GTPase‐BSE or K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE (19 μM) were pre‐incubated where indicated in the absence or presence of the relevant nucleotide or nucleotide analog (2 mM) for 1 h at 37°C. Samples were then loaded onto a Superdex 75 10/300 column (GE Healthcare) pre‐equilibrated in a running buffer of HN supplemented with 5 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM EGTA. The column was run at 0.5 ml/min. Absorbance was recorded at 280 nm.

4.7. Size‐exclusion chromatography coupled to multi‐angle light scattering (SEC‐MALS)

C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE was subjected to size‐exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 75 10/300 equilibrated in SEC‐MALS buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM MgCl2, 2.0 mM EGTA, and 2.0 mM β‐mercaptoethanol). Prior to size exclusion, K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE was preincubated (58.2 μM) in the absence or presence of various nucleotides or nucleotide analogs (2.0 mM) for 1 hr at 37°C, followed by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 10 min before injection. The gel filtration column was coupled to a static 18‐angle light scattering detector (DAWN HELEOS‐II) and a refractive index detector (Optilab T‐rEX) (Wyatt Technology). Data were collected continuously at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Data were analyzed using the program Astra VI. Monomeric BSA (6.0 mg/ml) (Sigma) was used for data quality control.

4.8. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)

ITC was used to determine the dissociation constants of C. therm Vps1 GTPase‐BSE or C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE for various nucleotides or nucleotide analogs. The titrations were performed at 25°C using a PEAQ‐ITC instrument (Malvern Analytical), in HN buffer supplemented with 5 mM MgCl2. 2.5 mM nucleotide or nucleotide analog was titrated into 50–100 μM protein. Integrated heat changes for each titration were fit to a single site binding model using the MicroCal PEAQ‐ITC software provided by the manufacturer.

4.9. Yeast media

YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose, supplemented with L‐tryptophan and adenine) was used for routine growth. YPGal substituted 2% galactose for glucose. Synthetic Defined (SD; yeast nitrogen base, ammonium sulfate, 2% glucose, appropriate amino acid dropout) or Synthetic Complete (SC; as for SD but with complete amino acid supplementation) were used prior to microscopy or to maintain plasmid selection. Cells were induced to sporulate by overnight incubation in YPA (2% potassium acetate, 2% peptone, 1% yeast extract) followed by incubation in SPO (1% potassium acetate, 0.1% yeast extract, 0.05% glucose).

4.10. Yeast genetic manipulation and molecular biology

Strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae used in this work are listed in Table S6. The DNM1 open reading frame was replaced with a kanamycin resistance cassette, amplified from pFA6a‐kanMX641 in W303A/α diploids by homologous recombination. Diploids were sporulated by starvation in SPO medium for 2 days. Following tetrad dissection, knockout haploids were extensively validated.

4.11. Preparation of yeast for microscopy

Cells were grown overnight in YPD or SD with appropriate supplementation to maintain plasmid selection. Cells were diluted in YPD and grown to mid‐logarithmic phase. Vacuolar membranes were stained with 10 μM FM 4–64 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 45 min, followed by washing and incubation in YPD without dye for 1 h. Immediately prior to imaging cells were resuspended in appropriately supplemented SD. Cells were plated on No. 1.5 glass‐bottomed coverdishes (MatTek Corporation, Ashland), treated with 15 μl 2 mg/ml concanavalin‐A (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis).

4.12. Confocal microscopy and image analysis

Confocal images were acquired on a Nikon (Melville, NY) A1 confocal, with a 100x Plan Apo 100x oil objective. NIS Elements Imaging software was used to control acquisition. Images were processed using the Fiji distribution of ImageJ.42

Supporting information

Table S1 Affinities of GMPPCP, GDP and GTP for C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE, as determined by ITC

Table S2. Basal GTP hydrolysis by C. therm Vps1 GTPase‐BSE or C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE, as assessed by the continuous, regenerative GTPase assay

Table S3. Plasmids used in this work

Table S4. Crystallographic data collection and processing

Table S5. Refinement statistics and model geometries

Table S6. Yeast strains used in this work

Figure S1. C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE does not dimerize in the presence of the non‐hydrolyzable GTP analog GMPPCP, GTP or GDP. Analytical size exclusion chromatography elution profiles of C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE in the presence of GMPPCP (blue), GTP (green) and GDP (magenta). The chromatogram of C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE in the absence of nucleotide (black) is duplicated from Figure 1a. The elution volumes of C. therm Vps1 GTPase‐BSE in the absence and presence of GDP.AlFx, indicating monomer and dimer respectively, are indicated with dotted vertical lines.

Figure S2. C. therm K56AVps1 assembles into few, intense puncta on the perivacuolar compartment in wild type (W303A) cells. When expressed in W303A, C. therm. Vps1‐EGFP distributed between the cytosol and dynamic perivacuolar puncta (top panels). By contrast, C. therm K56AVps1‐EGFP concentrated to few intense puncta at perivacuolar compartment. Some residual cytosolic staining was observed in these cells. Vacuoles were stained with FM 4–64. Scale bar—5 μm.

Figure S3. Overexpression of K42AVps1 in wild type yeast cells expressing Vps1‐EGFP induces formation of extended filament and a dominant‐negative effect on vacuolar morphology. To induce expression of K42AVps1, driven by the GAL1 promoter, cells were grown in YPGal for 24 hr prior to imaging. Vacuoles were stained with FM 4–64. Scale bar—5 μm.

Figure S4. Mitochondrial morphology in wild type (W303A) and Δdnm1 cells. Mitochondria were visualized using DsRed Express targeted to the mitochondrial matrix (Mito‐DsRed). Scale bar—5 μm.

Figure S5. K42AVps1 puncta do not associate with the mitochondrial network in Δvps1 cells. Mitochondria were visualized using DsRed Express targeted to the mitochondrial matrix (Mito‐DsRed). Scale bar—5 μm.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank William Furey, Simon Watkins, the Center for Biologic Imaging at the University of Pittsburgh and the beamline staffs at the Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER‐CAT). We also thank Robbie P. Joosten from PDB_REDO and the Netherlands Cancer Institute for advice with refinement. All final reflection data were collected at the SER‐CAT 22‐ID beamline at the APS, Argonne National Laboratory. Supporting institutions may be found at http://www.ser-cat.org/members.html. This research used resources of the APS, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE‐AC02‐06CH11357. Use of the APS was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. W‐31‐109‐Eng‐38. The isothermal titration calorimeter used in this work was purchased under NIH 1S10OD023481 (Angela Gronenborn). This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant GM120102 (M.G.J.F). The coordinates and structure factors for C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE, in complex with GMPPCP, have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code 6VJF.

Tornabene BA, Varlakhanova NV, Hosford CJ, Chappie JS, Ford MGJ. Structural and functional characterization of the dominant negative P‐loop lysine mutation in the dynamin superfamily protein Vps1. Protein Science. 2020;29:1416–1428. 10.1002/pro.3830

Funding information National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Grant/Award Number: GM120102; U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science, Grant/Award Numbers: W‐31‐109‐Eng‐38, DE‐AC02‐06CH11357

REFERENCES

- 1. Ford MGJ, Chappie JS. The structural biology of the dynamin‐related proteins: New insights into a diverse, multitalented family. Traffic. 2019;20:717–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Antonny B, Burd C, De Camilli P, et al. Membrane fission by dynamin: What we know and what we need to know. EMBO J. 2016;35:2270–2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bourne HR, Sanders DA, McCormick F. The GTPase superfamily: Conserved structure and molecular mechanism. Nature. 1991;349:117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vetter IR, Wittinghofer A. The guanine nucleotide‐binding switch in three dimensions. Science. 2001;294:1299–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leipe DD, Wolf YI, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Classification and evolution of P‐loop GTPases and related ATPases. J Mol Biol. 2002;317:41–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Praefcke GJ, McMahon HT. The dynamin superfamily: Universal membrane tubulation and fission molecules? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:133–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chappie JS, Acharya S, Leonard M, Schmid SL, Dyda F. G domain dimerization controls dynamin's assembly‐stimulated GTPase activity. Nature. 2010;465:435–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ford MG, Jenni S, Nunnari J. The crystal structure of dynamin. Nature. 2011;477:561–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Faelber K, Posor Y, Gao S, et al. Crystal structure of nucleotide‐free dynamin. Nature. 2011;477:556–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chappie JS, Mears JA, Fang S, et al. A pseudoatomic model of the dynamin polymer identifies a hydrolysis‐dependent powerstroke. Cell. 2011;147:209–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chappie JS, Dyda F. Building a fission machine–structural insights into dynamin assembly and activation. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:2773–2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van der Bliek AM, Redelmeier TE, Damke H, Tisdale EJ, Meyerowitz EM, Schmid SL. Mutations in human dynamin block an intermediate stage in coated vesicle formation. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:553–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Damke H, Baba T, Warnock DE, Schmid SL. Induction of mutant dynamin specifically blocks endocytic coated vesicle formation. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:915–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Otsuga D, Keegan BR, Brisch E, et al. The dynamin‐related GTPase, Dnm1p, controls mitochondrial morphology in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:333–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Varlakhanova NV, Alvarez FJD, Brady TM, et al. Structures of the fungal dynamin‐related protein Vps1 reveal a unique, open helical architecture. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:3608–3624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pai EF, Krengel U, Petsko GA, Goody RS, Kabsch W, Wittinghofer A. Refined crystal structure of the triphosphate conformation of H‐ras p21 at 1.35 a resolution: Implications for the mechanism of GTP hydrolysis. EMBO J. 1990;9:2351–2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sigal IS, Gibbs JB, D'Alonzo JS, et al. Mutant ras‐encoded proteins with altered nucleotide binding exert dominant biological effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:952–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Naylor K, Ingerman E, Okreglak V, Marino M, Hinshaw JE, Nunnari J. Mdv1 interacts with assembled dnm1 to promote mitochondrial division. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2177–2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. John J, Sohmen R, Feuerstein J, Linke R, Wittinghofer A, Goody RS. Kinetics of interaction of nucleotides with nucleotide‐free H‐ras p21. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6058–6065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Binns DD, Helms MK, Barylko B, et al. The mechanism of GTP hydrolysis by dynamin II: A transient kinetic study. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7188–7196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Narayanan R, Leonard M, Song BD, Schmid SL, Ramaswami M. An internal GAP domain negatively regulates presynaptic dynamin in vivo: A two‐step model for dynamin function. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:117–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dick A, Graf L, Olal D, et al. Role of nucleotide binding and GTPase domain dimerization in dynamin‐like myxovirus resistance protein a for GTPase activation and antiviral activity. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:12779–12792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sundborger AC, Fang S, Heymann JA, Ray P, Chappie JS, Hinshaw JE. A dynamin mutant defines a superconstricted prefission state. Cell Rep. 2014;8:734–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shalaeva DN, Cherepanov DA, Galperin MY, Golovin AV, Mulkidjanian AY. Evolution of cation binding in the active sites of P‐loop nucleoside triphosphatases in relation to the basic catalytic mechanism. Elife. 2018;7:e37373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ingerman E, Nunnari J. A continuous, regenerative coupled GTPase assay for dynamin‐related proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2005;404:611–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Raymond CK, Howald‐Stevenson I, Vater CA, Stevens TH. Morphological classification of the yeast vacuolar protein sorting mutants: Evidence for a prevacuolar compartment in class E vps mutants. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:1389–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gari E, Piedrafita L, Aldea M, Herrero E. A set of vectors with a tetracycline‐regulatable promoter system for modulated gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Yeast. 1997;13:837–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shaw JM, Nunnari J. Mitochondrial dynamics and division in budding yeast. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:178–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chappie JS, Acharya S, Liu YW, Leonard M, Pucadyil TJ, Schmid SL. An intramolecular signaling element that modulates dynamin function in vitro and in vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:3561–3571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Frohlich C, Grabiger S, Schwefel D, et al. Structural insights into oligomerization and mitochondrial remodelling of dynamin 1‐like protein. EMBO J. 2013;32:1280–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kong L, Sochacki KA, Wang H, et al. Cryo‐EM of the dynamin polymer assembled on lipid membrane. Nature. 2018;560:258–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Warnock DE, Hinshaw JE, Schmid SL. Dynamin self‐assembly stimulates its GTPase activity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22310–22314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Battye TG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, Leslie AG. iMOSFLM: A new graphical interface for diffraction‐image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Cryst. 2011;D67:271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. 2006;D62:72–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McCoy AJ, Grosse‐Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst. 2007;40:658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive python‐based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Cryst. 2010;D66:213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Murshudov GN, Skubak P, Lebedev AA, et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Cryst. 2011;D67:355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Cryst. 2010;D66:486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Joosten RP, Long F, Murshudov GN, Perrakis A. The PDB_REDO server for macromolecular structure model optimization. IUCr J. 2014;1:213–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System , Version 1.7.6, Schrödinger, LLC. [computer program]; 2015.

- 41. Longtine MS, McKenzie A 3rd, Demarini DJ, et al. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR‐based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schindelin J, Arganda‐Carreras I, Frise E, et al. Fiji: An open‐source platform for biological‐image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Affinities of GMPPCP, GDP and GTP for C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE, as determined by ITC

Table S2. Basal GTP hydrolysis by C. therm Vps1 GTPase‐BSE or C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE, as assessed by the continuous, regenerative GTPase assay

Table S3. Plasmids used in this work

Table S4. Crystallographic data collection and processing

Table S5. Refinement statistics and model geometries

Table S6. Yeast strains used in this work

Figure S1. C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE does not dimerize in the presence of the non‐hydrolyzable GTP analog GMPPCP, GTP or GDP. Analytical size exclusion chromatography elution profiles of C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE in the presence of GMPPCP (blue), GTP (green) and GDP (magenta). The chromatogram of C. therm K56AVps1 GTPase‐BSE in the absence of nucleotide (black) is duplicated from Figure 1a. The elution volumes of C. therm Vps1 GTPase‐BSE in the absence and presence of GDP.AlFx, indicating monomer and dimer respectively, are indicated with dotted vertical lines.

Figure S2. C. therm K56AVps1 assembles into few, intense puncta on the perivacuolar compartment in wild type (W303A) cells. When expressed in W303A, C. therm. Vps1‐EGFP distributed between the cytosol and dynamic perivacuolar puncta (top panels). By contrast, C. therm K56AVps1‐EGFP concentrated to few intense puncta at perivacuolar compartment. Some residual cytosolic staining was observed in these cells. Vacuoles were stained with FM 4–64. Scale bar—5 μm.

Figure S3. Overexpression of K42AVps1 in wild type yeast cells expressing Vps1‐EGFP induces formation of extended filament and a dominant‐negative effect on vacuolar morphology. To induce expression of K42AVps1, driven by the GAL1 promoter, cells were grown in YPGal for 24 hr prior to imaging. Vacuoles were stained with FM 4–64. Scale bar—5 μm.

Figure S4. Mitochondrial morphology in wild type (W303A) and Δdnm1 cells. Mitochondria were visualized using DsRed Express targeted to the mitochondrial matrix (Mito‐DsRed). Scale bar—5 μm.

Figure S5. K42AVps1 puncta do not associate with the mitochondrial network in Δvps1 cells. Mitochondria were visualized using DsRed Express targeted to the mitochondrial matrix (Mito‐DsRed). Scale bar—5 μm.