Abstract

Background

Diagnosis of pancreatic diseases in dogs is still challenging because of variable clinical signs, which do not always correspond with clinical pathology and histopathological findings.

Objectives

To characterize inflammatory and neoplastic pancreatic diseases of dogs and to correlate these findings with clinical findings and canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (cPLI) results.

Animals

Tissue specimens and corresponding blood samples from 72 dogs submitted for routine diagnostic testing.

Methods

Four groups were defined histologically: (1) normal pancreas (n = 40), (2) mild pancreatitis (n = 8), (3) moderate or severe pancreatitis (acute, n = 11; chronic, n = 1), and (4) pancreatic neoplasms (n = 12). An in‐house cPLI ELISA (<180 μg/L, normal; >310 μg/L, pancreatitis) was performed.

Results

In dogs with normal pancreas, 92.5% of serum cPLI results were within the reference range and significantly lower than in dogs with mild acute pancreatitis, moderate or severe acute pancreatitis and pancreatic tumors. In dogs with moderate or severe acute pancreatitis, cPLI sensitivity was 90.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 58.7%‐99.8%). Most dogs (9/12) with pancreatic tumors (group 4) had additional pancreatic inflammation and cPLI results were increased in 10 dogs.

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

High cPLI indicates serious acute pancreatitis but underlying pancreatic neoplasms should also be taken into consideration. This study confirms the relevance of histopathology in the diagnostic evaluation of pancreatic diseases.

Keywords: dog, lipase, pancreatitis, pathology, tumor

Abbreviations

- cPL

canine pancreatic lipase

- cPLI

canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity

- CS

Christina Stadler

- DGGR

1,2‐o‐dilauryl‐rac‐glycero‐3‐glutaric acid‐(6′‐methylresorufin) ester

- HA‐L

Heike Aupperle‐Lellbach

- HEK

human embryonic kidney cells

- KT

Katrin Törner

- OD

optical density

- RIA

radioimmunoassay

- TMB

tetramethylbenzine

1. INTRODUCTION

Pancreatitis is a common disease in dogs, but it is still challenging to diagnose because of nonspecific and variable clinical signs, such as vomiting, anorexia, and abdominal discomfort. 1 In contrast, exocrine pancreatic neoplasms are rarely found in dogs. 2 Clinical signs are mostly similar to those of pancreatitis (eg, vomiting, polyuria, polydipsia, palpable intraabdominal mass).3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Furthermore, in most cases of primary pancreatic carcinomas, clinical pathology also identifies increased pancreas‐specific and inflammatory test results.3, 8, 9, 10, 11

If pancreatitis is suspected, a CBC and serum biochemistry profile are recommended to assess the patient, although changes may be nonspecific. 12 An increase in serum lipase activity might indicate pancreatitis,13, 14 but depending on the lipase substrate used, results also may be increased in patients with hepatic or renal diseases,10, 15 as well as in those with gastritis. 16 Specific tests, such as radioimmunoassays (RIA) or ELISA, are necessary to distinguish pancreatic‐specific lipase from lipase of other origin. However, the 1,2‐o‐dilauryl‐rac‐glycero‐3‐glutaric acid‐(6′‐methylresorufin) ester (DGGR) assay shows high correlation with a specific ELISA.17, 18 Canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (cPLI) is reported to have variable sensitivity, ranging from 21 to 90.9%, whereas specificity ranges from 74.1 to 100%.19, 20, 21, 22, 23

Histopathology is widely accepted as the gold standard for the diagnosis of pancreatitis because it is the only method to identify its extent, character and chronicity as well as to distinguish it from neoplastic processes, because of nonspecific gross findings.24, 25 Cytology also may be useful in the diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma. 25 Pancreatic biopsy can be performed during abdominal laparotomy. 26 However, both cytology and histopathology are performed infrequently. Ultrasonography is a noninvasive diagnostic tool that avoids tissue damage caused by biopsy sampling.12, 25 Furthermore, ultrasonography may be useful to differentiate endocrine from exocrine pancreatic tumors, but final diagnosis still requires histopathology.5, 7

Our aim was to perform a detailed histopathological characterization of inflammatory and neoplastic pancreatic diseases in dogs and correlate these findings to clinical findings and results of an in‐house cPLI assay.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Histopathology

Pancreatic tissue specimens from 1034 dogs submitted between 2012 and 2019 for routine diagnostic testing were evaluated. Simultaneous serum samples including cPLI results and clinical data were available from 72 dogs and evaluated retrospectively. Pancreatic samples and additional organ biopsy samples were obtained during elective exploratory surgery (n = 54), but pancreatic biopsy site was not reported. The entire pancreas was available if animals were euthanized (n = 18). Tissue samples were stored in 10% buffered formalin. Serum samples must have been collected no longer than 2 days before biopsy or euthanasia, and promptly submitted to the laboratory. All dogs with adequate histological sample quality, cPLI result, and sufficient clinical data were included. Dogs with endocrine neoplasms were excluded from the study.

Gross changes of the tissue samples were documented. Pancreatic tissue was sectioned every 0.5 cm, and, depending on the size of the sample, 1 to 15 representative tissue sections were routinely embedded in Paraplast TM (SAV‐liquid Production GmbH, Flintsbach am Inn, Germany; PFNP‐20‐5858‐1) and stained with hematoxylin‐eosin. Slides were evaluated by a veterinary pathologist (HA‐L, German Fachtierarzt für Pathologie) and blindly controlled by a second veterinary pathologist (CS, German Fachtierarzt für Pathologie) and a trainee pathologist (KT). Dogs were grouped according to histopathological criteria of pancreatic diseases27, 28:

Group 1 (“normal pancreas”): no or minimal interstitial infiltration of lymphocytes, mild interstitial fibrosis, mild nodular hyperplasia or some combination of these.

Group 2 (“mild pancreatitis”): mild infiltration of neutrophils and some lymphocytes and macrophages with few small foci of acute acinar vacuolar degeneration or necrosis (<10% of the sections affected).

Group 3 (“moderate or severe pancreatitis”: moderate, 10%‐40%, and severe, >40% of the sections affected): This group included moderate to severe “acute pancreatitis” (neutrophils, extensive areas of necrosis with destruction of pancreatic acini and fat tissue) and “acute‐on‐chronic pancreatitis” (purulent and necrotizing inflammation in addition to areas with granulation tissue and fibrosis) as well as “chronic pancreatitis” (presence of extensive fibrosis with acinar atrophy but without necrosis).

Group 4 (“pancreatic neoplasms”): diagnosed according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the alimentary system of domestic animals, 29 and neoplasms were classified as primary or secondary depending on histogenesis.

2.2. Determination of cPLI

For the quantification of cPLI in serum samples, an in‐house indirect sandwich ELISA assay was developed. In short, human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293) were transiently transfected with a recombinant His‐tagged plasmid containing the cDNA sequence for canine pancreatic lipase (cPL; GenScript, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The antigen was purified using immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography (HiTrap IMAC HP, GE Healthcare, Chalfont St Giles, UK). The recombinant protein was then used to raise polyclonal antibodies against cPL in New Zealand White rabbits. Antibodies were used both as capture antibodies as well as detection antibodies after biotinylation. The recombinant cPL was used to prepare a standard dilution with concentrations ranging from 0 to 1000 μg/L. Both standard samples and serum samples were incubated in a microtiter plate coated with cPL antibodies for 60 minutes at room temperature. After that, they were washed and then incubated with biotinylated antibodies against cPL for 60 minutes. A streptavidin‐peroxidase conjugate (Hoffmann‐La Roche, Basel, Switzerland) was added for 20 minutes. The enzymatic reaction was stopped 15 minutes after the addition of tetramethylbenzidine (TMB‐one solution) using sulfuric acid. Optical density (OD) values were determined spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 630 nm.

The detection range of the cPLI ELISA was 5 to 1000 μg/L, with a limit of detection of 2.0 μg/L. Serial dilutions of serum samples for linearity assessment of the assay showed a ratio of calculated to observed results between 5.0% and 6.4%. Correlation of cPLI concentrations of 63 serum samples measured against the Spec cPLI ELISA (Gastrointestinal Laboratory, Texas A&M University, College Station, USA) was r = 0.86. The reference ranges were defined as “normal” (cPLI <180 μg/L), “questionable” (cPLI 180‐310 μg/L), and “consistent with pancreatitis” (cPLI >310 μg/L). These reference values were validated using our data set. The test precision was determined by means of 3 canine serum samples (normal, medium, high concentration). The intra‐assay variations were calculated from 5 replicates within a test run, respectively, with variation coefficients from 3.6% to 5.0%. For interassay variation, 4 replicates were each tested in different runs with variation coefficients of 4.7% to 11.4%.

Additional clinical pathology variables (eg, CBC, liver and kidney function tests) were investigated for routine diagnostic purposes but are not included in the study. The final diagnoses, based on all clinical, serologic, and pathologic findings, were provided afterward by the clinicians and are listed in supplemental files.

Statistical analysis was done using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25) with the Kruskal‐Wallis test. Specificity, sensitivity and the 95% confidence intervals (CI) of both were calculated based on the cutoff concentrations of >180 μg/L and >310 μg/L, respectively, using MedCalc Statistical Software version 19.1.3 (MedCalc Software bv, Ostend, Belgium; https://www.medcalc.org; 2019).

3. RESULTS

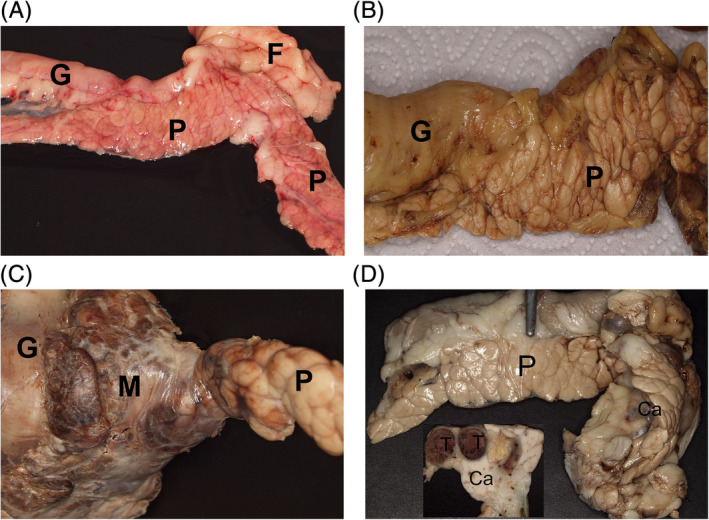

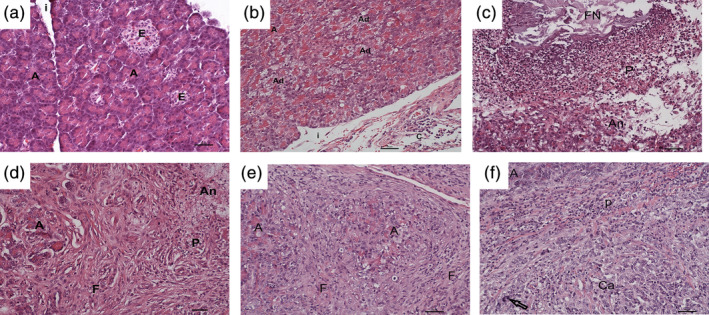

The median age of all dogs included in the study was 9 years (range 1‐14 years). The cohort consisted of 39 males (23 intact, 16 neutered) and 33 females (15 intact, 18 spayed). The most common breeds were 12 Labrador Retrievers, various Terrier breeds (n = 16), 7 mongrels, 4 poodles, 3 German shepherds, and 3 Maltese dogs. Pancreata of 40 dogs were found to be normal, 8 dogs had mild pancreatitis, 12 were categorized as having moderate or severe pancreatitis, and 12 samples showed primary or secondary epithelial neoplasms within the pancreas. Macroscopic features are shown in Figure 1 and histological findings in Figure 2.

FIGURE 1.

Macroscopic appearance of the pancreas in the different groups: A, normal, smooth, light red pancreas (P), gut (G), and smooth white fat tissue (F) (9‐year‐old Labrador, group 1; unfixed tissue), B, pancreatic tissue (P) with prominent lobular structure and histologically mild acute interlobular inflammation and part of the gut (G) (14‐year‐old West Highland White Terrier, group 2; formalin‐fixed tissue), C, focal severe acute purulent‐necrotising inflammation of the pancreas (P) appears grossly as a firm dark‐brown mass (M) close to the gut (G) (3‐year‐old Labrador, group 3; formalin‐fixed tissue), D, the acinar pancreatic carcinoma (Ca) is a firm mass within the pancreas (P). Inset: cut surface with homogenous white firm carcinoma mass (Ca) and thrombosed vessels (T) (5‐year‐old Flat‐Coated Retriever, group 4; formalin‐fixed tissue)

FIGURE 2.

Histopathological findings of the pancreas in the different groups. A, normal pancreas composed of normal acini (A) separated by thin interstitial septa (i) and endocrine islets (E) (6‐year‐old Elo, group 1; HE, bar = 50 μm). B, normal acini (A) and multifocal acini with mild to moderate vacuolar degeneration (Ad) and mild interstitial (i) mixed cellular pancreatitis (14‐year‐old West Highland White Terrier, group 2; HE, bar = 50 μm). C, severe fat tissue necroses (FN), purulent (P) inflammation and necroses of pancreatic acini (An) in a case of severe acute pancreatitis (2‐year‐old Labrador, group 3; HE, bar = 50 μm). D, few normal acini (A) surrounded by severe fibrosis (F) and areas with purulent (P) inflammation and acinar necrosis (An) in a case of” acute‐on‐chronic” pancreatitis (10‐year‐old Maltese, group 3; HE, bar = 50 μm). E, few normal acini (A) surrounded by severe fibrosis (F) in a case of severe chronic mixed inflammation with moderate acinar atrophy (8‐year‐old Russian Tsvetnaya Bolonka, group 3; HE, bar = 50 μm). F, acinar pancreatic carcinoma (Ca) with nuclear atypia (arrow) and peripheral purulent inflammation (P), focally some normal acini (A) (5‐year‐old Flat‐Coated Retriever, group 4; HE, bar = 50 μm)

3.1. Group 1—normal pancreas

The 40 dogs in this group were 1 to 14 years old (median, 8 years). The most common breeds were Terriers (n = 9) and Labrador Retrievers (n = 6). Sex distribution was 17 females (6 intact, 11 spayed) and 23 males (16 intact, 7 neutered). The main clinical signs were vomiting (n = 19), diarrhea (n = 18), painful (n = 10) or enlarged (n = 2) abdomen, weight loss (n = 5), jaundice (n = 3), increased liver enzyme activity (n = 2), or neurological signs (n = 2). Clinically suspected diseases or main tentative diagnoses after first clinical investigations were gastritis or enteritis (n = 25), abdominal neoplasm (n = 8), hepatic (n = 4) or pancreatic (n = 1) diseases, and other (n = 4). Based on these findings, exploratory laparotomy with sample collection of several organs was performed.

Grossly, the pancreas had a pale‐reddish color and lobules were separated by a thin interstitium (Figure 1A). Histopathologically, the structure of the exocrine pancreas was normal (n = 28; Figure 2A) or had nodular hyperplasia (n = 10). In few cases, interstitial hemorrhage (n = 2) or mild interstitial fibrosis (n = 1) was observed. In 37 of the 40 dogs with normal pancreas, the serum concentrations of cPLI were within the reference range (5.0‐159.4 μg/L; median, 38.9 μg/L; specificity, 92.5%; 95% CI, 79.6%‐98.4%; Table 1). However, in a single 6‐year‐old Elo (gastritis, enteritis), a 12‐year‐old mongrel (lymphoma) and a 8‐years‐old Jack Russell Terrier (abdominal pain, enteritis), pancreatic biopsy results were normal, but cPLI concentration was elevated (183.9 μg/L, 297.4 μg/L and > 600 μg/L, respectively). Based on all findings, the main relevant final diagnoses for dogs in group 1 were gastritis or enteritis (n = 19), abdominal neoplasm (n = 6), liver disease (n = 11), peritonitis (n = 2), intoxication (n = 1), and gall bladder mucocele (n = 1).

TABLE 1.

cPLI values in 59 cases of histologically normal pancreas (group 1), mild pancreatitis (group 2), or moderate/severe acute pancreatitis (11/12 of group 3)

| Normal pancreas (n = 40) | Mild pancreatitis (n = 8) | Moderate/severe acute pancreatitis (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Consistent with pancreatitis (n = 15) cPLI >310 μg/L |

1 | 5 | 9 |

|

Questionable (n = 4) cPLI 180‐310 μg/L |

2 | 1 | 1 |

|

Normal (n = 40) cPLI <180 μg/L |

37 | 2 | 1 |

| Specificity 92.5% (95% CI, 79.6%‐98.4%) |

Sensitivity >180 μg/L:75% (95% CI, 34.9‐96.8%) >310 μg/L: 62.5% (95% CI, 24.5‐91.5%) |

Sensitivity >180 μg/L: 90.9% (95% CI, 58.7%‐99.8%) >310 μg/L: 81.8% (95% CI, 71.5%‐100.0%) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval; cPLI, canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity.

3.2. Group 2—mild pancreatitis

The age of the 8 dogs in this group ranged from 3 to 14 years (median, 10 years). Included were 4 female (2 intact, 2 spayed) and 4 male dogs (3 intact, 1 neutered). Most common clinical signs included vomiting (n = 3), painful (n = 2) or enlarged (n = 3) abdomen, weight loss (n = 2), diarrhea (n = 2), or some combination of these. After clinical assessment, the following diagnoses were suspected: abdominal neoplasm (n = 3), enteritis (n = 3), hepatic (n = 2) or pancreatic (n = 2) diseases, and peritonitis (n = 2).

Grossly, the pancreas seemed normal or occasionally with prominent lobules (Figure 1B). Histopathologically, the interlobular septa of the exocrine pancreas had mild diffuse or multifocal mixed cellular inflammation (n = 5) (Figure 2B) or mild chronic lymphoplasmacytic pancreatitis with mild fibrosis and multifocal degeneration of some acinar cells (n = 1). In 3 cases, mild purulent (n = 2) or necrotizing (n = 1) pancreatitis was present. In 5 dogs, the adjacent adipose tissue had mild (n = 3) or severe (n = 2) steatitis ranging from acute purulent (n = 2) or chronic purulent to pyogranulomatous with formation of granulation tissue (n = 3).

Sensitivity of cPLI in dogs with mild acute pancreatitis was 75% (95% CI, 34.9%‐96.8%) at the cutoff concentration of 180 μg/L and 62.5% (95% CI, 24.5%‐91.5%) at the cutoff concentration of 310 μg/L (Table 1). Two dogs with histologically confirmed liver disease had serum cPLI concentrations within the normal range (111.6 and 149.4 μg/L). A 7‐year‐old Maltese with trauma‐induced peritonitis had a cPLI of 184.6 μg/L. Five dogs with histologically confirmed degenerative, inflammatory or neoplastic liver diseases (n = 4) or an intestinal foreign body (n = 1) had high cPLI concentrations (median, 458.1 μg/L; range, 314.7 to >600 μg/L). There was no correlation of cPLI with the type or chronicity of mild pancreatitis or with the severity of peripancreatic steatitis within the submitted samples.

For the animals of group 2, final main diagnoses, based on all findings, were liver disease (n = 5), trauma or foreign body‐related peritonitis (n = 2) and neoplasm (n = 1). Mild pancreatitis and peripancreatic steatitis were not the most clinically relevant condition in the majority of the dogs in group 2.

3.3. Group 3—moderate or severe pancreatitis

The 12 dogs in this group were 2 to 13 years old (median, 9 years). Four were females (1 intact, 3 spayed) and 8 were males (3 intact, 5 neutered). The most common breed was Labrador Retriever (n = 5). Vomiting was the main clinical finding in 9 of the 12 dogs in this group. Additional signs included painful (n = 6) or enlarged (n = 2) abdomen, jaundice (n = 2), diarrhea (n = 2), lethargy (n = 2), and collapse (n = 2). Clinically suspected diseases were neoplasm (n = 7), pancreatitis (n = 5), liver disease (n = 2), and intoxication (n = 2).

Grossly, the pancreas was thickened, lobules were prominent, with ≥1 firm masses of variable size. Masses often had dark‐brown (hemorrhagic) and thickened interlobular septa (Figure 1C). In cases with necrotizing steatitis, the adipose tissue was firm and white to brown in color.

Histopathologically, pancreatic samples contained moderate (n = 4) or severe (n = 8) inflammation in dogs of group 3. In 8 of 12 cases, tissue sections with severe necrotizing‐purulent steatitis also were submitted. In 1 dog, periductal inflammation was dominant whereas all other cases had interlobular and intralobular inflammatory patterns.

In 6 dogs, inflammation of the pancreas and adipose tissue was characterized as acute purulent with necrosis, and infiltration of the interlobular septa and acinar parenchyma (intralobular) with neutrophils and few macrophages; (Figure 2C). Pancreatic samples of 5 dogs had “acute‐on‐chronic” inflammation with areas of acute necrosis and purulent inflammation next to granulation tissue and fibrosis. Inflammatory and fibrotic processes were present in adipose tissue as well as in pancreatic parenchyma. Distribution was mainly interlobular and multifocal intralobular (Figure 2D). The final diagnosis in 11 dogs was moderate or severe acute pancreatitis.

One dog had moderate to severe chronic pancreatitis. Few mixed inflammatory cells were present, and a large amount of fibrosis separated the markedly atrophic pancreatic parenchyma (Figure 2E). The acinar cells were unaffected and the cPLI concentration was within the reference range (149.9 μg/L). The main clinical finding was a posthepatic jaundice.

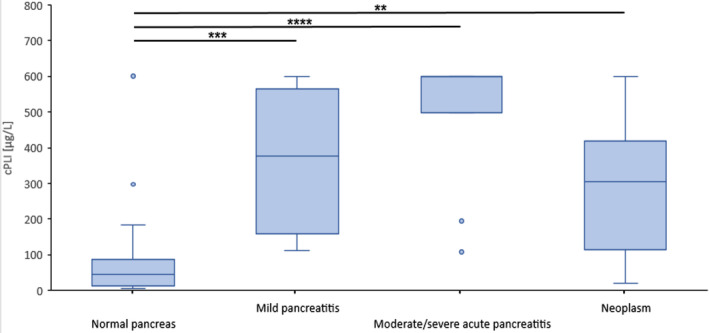

In summary of groups 1‐3, cPLI concentration of dogs with normal pancreas were significantly lower than those of dogs with mild acute pancreatitis (P = .001) and those with moderate or severe acute pancreatitis (P < .001; Figure 3). In 10 out of 11 dogs with moderate or severe acute pancreatitis, high cPLI concentrations were detected (sensitivity, 90.9%; 95% CI, 58.7%‐99.8%). However, in 1 dog with histopathologically confirmed severe acute pancreatitis, the cPLI concentration was within the reference range (107.8 μg/L; Table 1).

FIGURE 3.

Dogs with mild pancreatitis (group 2, n = 8), moderate or severe acute pancreatitis (group 3, 11/12) or neoplasm (group 4, n = 12) had significantly higher values of canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (cPLI) than dogs with histologically confirmed normal pancreas (group 1, n = 40). Boxes indicate the lower to upper quartile (25th‐75th percentile) and median value. Whiskers extend to minimum and maximum values, with outliers shown as individual points (**P = .005, ***P = .001, **** P < .001)

3.4. Group 4—pancreatic neoplasms

The 12 dogs in this group were 5 to 14 years old (median, 11 years). Eight dogs were females (6 intact, 2 spayed) and 4 were males (1 intact, 3 neutered). Three dogs were Retriever breeds and 2 were Terrier breeds. Vomiting was the main clinical finding in 8 of the 12 dogs in this group. Additional signs included anorexia (n = 3), weight loss (n = 4), jaundice (n = 4), diarrhea (n = 2), lethargy (n = 1), painful abdomen (n = 1), anemia (n = 1), and hematuria (n = 1). Clinically suspected diseases were neoplasms (n = 11) and peritonitis (n = 1). Laparotomy and tissue sampling or necropsy after euthanasia were performed to confirm the diagnoses.

Five dogs suffered from acinar pancreatic carcinomas with masses up to 8.0 × 4.0 × 4.0 cm or diffuse thickened areas with homogenous white‐brown cut surface and loss of lobular structure (Figure 1D). In all pancreatic acinar carcinomas, the cPLI concentrations were increased (median, 382.8 μg/L; range, 235.2‐490.5 μg/L). In 3 cases, carcinomas were accompanied by moderate or severe focal necrosis and multifocal chronic mixed cellular inflammation (Figure 2F). Only a small biopsy sample was available from a 13‐year‐old Yorkshire Terrier with a high cPLI concentration and included a small portion of a neoplasm and a rim of normal pancreatic tissue with no associated inflammation.

In a West Highland White Terrier with a 0.5 cm adenoma, mild lymphoplasmacytic interlobular inflammation was present and the cPLI concentration was normal (166.0 μg/L). A 14‐year‐old Labrador with ductal pancreatic carcinoma had severe lymphoplasmacytic interlobular inflammation with severe acinar atrophy and normal cPLI concentration (19.2 μg/L). A 9‐year‐old poodle with ductal pancreatic carcinoma without additional inflammation also had normal cPLI concentration (131.4 μg/L).

Four dogs had pancreatic metastases of other carcinomas (gastric carcinoma, n = 2; liver carcinoma, n = 1; unknown origin, n = 1) within the pancreatic parenchyma. In 2 cases, the remaining pancreatic tissue was normal or had mild neutrophilic infiltration of the interlobular septa, and cPLI concentrations were within the reference range (42.5 and 110.1 μg/L, respectively). A Collie with gastric carcinoma metastases and mild interlobular and periductal pancreatitis had an increased cPLI concentration (374.8 μg/L). One Golden Retriever had numerous metastases of a hepatocellular carcinoma and multifocal areas of moderate acute pancreatic necrosis, and the cPLI concentration was markedly increased (>600 μg/L).

The cPLI concentrations of dogs with neoplasms were significantly higher (P = .005) than those of dogs with normal pancreas (group 1), but not different from dogs with mild (group 2) or moderate or severe acute pancreatitis (group 3; Figure 3).

4. DISCUSSION

In most cases, the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is made based on history, and clinical and laboratory findings, including cPLI concentration. Although histopathology is considered the gold standard, other diagnostic tests were mostly validated by other methods because histopathology was not available in most studies. 12 Only 2 studies on pancreatic lipase in dogs have been published, distinguishing cases with normal pancreas or mild or severe pancreatitis based on histology.19, 20 In our study, we compared various histopathologically confirmed pancreatic findings to results of an in‐house cPLI test with good agreement. Specificity was 92.5% (95% CI, 79.6%‐98.4%) and sensitivity was 90.9% (95% CI, 58.7%‐99.8%) in moderate or severe acute pancreatitis (Table 1). The concentrations of cPLI in control dogs were significantly lower than in dogs with mild pancreatitis, moderate or severe pancreatitis, or pancreatic neoplasms (Figure 3). In the veterinary literature, depending on the cutoff, the sensitivity in mild pancreatitis was 43% (>200 μg/L) or 21% (>400 μg/L). 19 In moderate or severe pancreatitis, sensitivity was 71% independent of the cutoff. 19 With a cutoff of 200 μg/L, a previous study 21 found a higher sensitivity (86.5%‐93.6%) for detection of acute pancreatitis than did our study (75%). Choosing 400 μg/L as a cutoff, sensitivity in the veterinary literature ranged from 33.0% to 90.9% and specificity from 74.1% to 90.0%.20, 21, 22, 23 One study found a markedly lower specificity of 66.3% to 77.0%. 21

In our study, the median age of dogs with moderate or severe pancreatitis was 9 years, which is in accordance with the veterinary literature. 28 Breed predispositions as described in the United Kingdom or the United States were not found in our group of dogs with mild or moderate or severe pancreatitis.30, 31, 32 The high number of Labrador Retrievers and Terrier breeds in groups 1, 2, and 3 probably reflects the frequency of these breeds within the dog population in Germany and should not be interpreted as true breed predisposition. One study described a pattern of periductal pancreatitis in Boxers and Cocker Spaniels, but these breeds were not present in our population. 33 In our study, in contrast, a Mongrel and a Collie had periductal pancreatitis.

As described in several studies, it is very important to differentiate acute from chronic pancreatitis by means of histopathology.34, 35 However, from the clinical perspective, acute phases of chronic pancreatitis will present similarly to acute pancreatitis.28, 35 This was confirmed in 5 cases in group 3 with acute‐on‐chronic pancreatitis that had increased cPLI concentrations. In contrast, 1 dog suffered from moderate or severe chronic pancreatitis and had a normal cPLI concentration.

One inconclusive case had moderate or severe acute pancreatitis and normal cPLI concentration. Similar cases were evaluated in another study, with no evident explanation. 20 Two cases in group 1 had increased cPLI concentration that were attributed to inflammation elsewhere 36 or to individual daily variation. 37

A limitation of our study was its retrospective design that only included the main findings and not treatment or follow‐up information. However, in order to interpret cPLI concentration, all diagnostic data (clinical findings, clinical pathology, histopathology) must be taken into account. The few cases with mild (n = 8) and moderate or severe (n = 12) pancreatitis, however, are similar to those of other studies. 12

Unlike in dogs, pancreatic ductal carcinomas in humans are common, whereas acinar carcinomas are rare. 38 In people, pancreatic enzyme measurement does not distinguish between ductal carcinoma and other pancreatic conditions, such as chronic pancreatitis or mucinous cystic lesions. 39 However, serum lipase activity may be helpful for the diagnosis and monitoring of patients acinar cell carcinoma. 40 In 4 of 5 dogs with pancreatic carcinoma, serum lipase activity was increased. 25 Also, dogs with secondary pancreatic neoplasms may have increased cPLI concentrations. 41 A main finding is that pancreatic acinar carcinomas may be accompanied by severe inflammation, which leads to increased serum cPLI concentration. Tumors originating elsewhere seemed to cause vascular embolism with subsequent ischemic necrosis and pancreatitis. Primary or secondary neoplasms without associated inflammation, on the other hand, did not result in increased cPLI concentrations. In conclusion, histopathological examination is necessary to detect neoplasms, which may be clinically and serologically overlooked because of overlapping inflammation.

In summary, in our study, high cPLI concentrations indicated acute pancreatitis although underlying primary or secondary pancreatic neoplasms could not be completely ruled out. A negative cPLI test result may miss some cases of acute or chronic inactive pancreatitis as well as pancreatic neoplasms without inflammation. Thus, a combination of clinical examination, clinical pathology and histopathology improves the diagnosis of inflammatory, degenerative, and neoplastic pancreatic diseases in dogs.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DECLARATION

Heike Aupperle‐Lellbach, Katrin Törner, Christina Stadler, Ursula Tress, Julia M. Grassinger, Elisabeth Müller, and Corinna N. Weber are employed by Laboklin GmbH & Co KG, Bad Kissingen, Germany that provided the performed tests.

OFF‐LABEL ANTIMICROBIAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC) OR OTHER APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no IACUC or other approval was needed.

HUMAN ETHICS APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare human ethics approval was not needed for this study.

Supporting information

Supplementary Table 1 Signalment, clinical findings, cPLI values in dogs with histopathologically diagnosed normal or minimally changed pancreas (group 1, n = 40)

Supplementary Table 2 Signalment, clinical findings, cPLI values in dogs with histopathologically diagnosed mild pancreatitis (group 2, n = 8)

Supplementary Table 3 Signalment, clinical findings, cPLI values in dogs with histopathologically diagnosed acute and chronic moderate / severe pancreatitis (group 3, n = 12)

Supplementary Table 4 Signalment, clinical findings, cPLI values in dogs with neoplasm within the pancreas (group 4, n = 12)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Daniela Collen and Elaine Taylor for corrections as native English speakers, and Anja Coelfen for help in collecting the samples.

Aupperle‐Lellbach H, Törner K, Staudacher M, et al. Histopathological findings and canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity in normal dogs and dogs with inflammatory and neoplastic diseases of the pancreas. J Vet Intern Med. 2020;34:1127–1134. 10.1111/jvim.15779

REFERENCES

- 1. Ruaux CG. Diagnostic approaches to acute pancreatitis. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2003;18:245‐249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aupperle‐Lellbach H, Törner K, Staudacher M, Müller E, Steiger K, Klopfleisch R. Characterisation of 22 canine pancreatic carcinomas and review of literature. J Comp Pathol. 2019;173:71‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anderson NV, Johnson KH. Pancreatic carcinoma in the dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1967;50:195‐286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bright JM. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma in a dog with maldigestion syndrome. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1985;187:420‐421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lamb CR, Simpson KW, Boswood A, Matthewman LA. Ultrasonography of pancreatic neoplasia in the dog: a retrospective review of 16 cases. Vet Rec. 1995;137:65‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pavone S, Manuali E, Eleni C, Ferrari A, Bonanno E, Ciorba A. Canine pancreatic clear acinar cell carcinoma showing an unusual mucinous differentiation. J Comp Pathol. 2011;145:355‐358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vanderperren K, Haers H, Van der Vekens E, et al. Description of the use of contrast‐enhanced ultrasonography in four dogs with pancreatic tumours. J Small Anim Pract. 2013;55:164‐169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cello RM, Olander H. Cord compression and paraplegia in a dog secondary to pancreatic carcinoma. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1963;142:1407‐1412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bleicher DD. Canine pancreatic adenocarcinoma (a case report). Vet Med. 1976;71:43‐45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Quigley KA, Jackson ML, Haines DM. Hyperlipasemia in 6 dogs with pancreatic or hepatic neoplasia: evidence for tumor lipase production. Vet Clin Pathol. 2001;30:114‐120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gear RNA, Bacon NJ, Langley‐Hobbs S, Watson PJ, Woodger N. Panniculitis, polyarthritis and osteomyelitis associated with pancreatic neoplasia in two dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 2006;47:400‐404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lidbury JA, Suchodolski JS. New advances in the diagnosis of canine and feline liver and pancreatic disease. Vet J. 2016;215:87‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Steiner JM. Diagnosis of pancreatitis. Vet Clin N Am‐Small. 2003;33:1181‐1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chartier MA, Hill SL, Sunico S, Suchodolski JS, Robertson JE, Steiner JM. Pancreas‐specific lipase concentrations and amylase and lipase activities in the peritoneal fluid of dogs with suspected pancreatitis. Vet J. 2014;201:385‐389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Polzin DJ, Osborne CA, Stevens JB, Hayden DW. Serum amylase and lipase activities in dogs with chronic primary renal failure. Am J Vet Res. 1983;44:404‐410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Willard MD. Diseases of the stomach In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, eds. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1995:1143‐1168. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kook PH, Kohler N, Hartnack S, Riond B, Reusch CE. Agreement of serum spec cPL with the 1,2‐o‐dilauryl‐rac‐glycero glutaric acid‐(6′‐methylresorufin) ester (DGGR) lipase assay and with pancreatic ultrasonography in dogs with suspected pancreatitis. J Vet Intern Med. 2014;28:863‐870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hurth SP, Relford R, Steiner JM, et al. Analytical validation of an ELISA for measurement of canine pancreas‐specific lipase. Vet Clin Pathol. 2010;39:346‐353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trivedi S, Marks SL, Kass PH, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of canine pancreas‐specific lipase (cPL) and other markers for pancreatitis in 70 dogs with and without histopathologic evidence of pancreatitis. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25:1241‐1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mansfield CS, Anderson GA, O'Hara AJ. Association between canine pancreatic‐specific lipase and histologic exocrine pancreatic inflammation in dogs: assessing specificity. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2012;24:312‐318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McCord K, Morley PS, Armstrong J, et al. A multi‐institutional study evaluating the diagnostic utility of the spec cPL and SNAP(R) cPL in clinical acute pancreatitis in 84 dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2012;26:888‐896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haworth MD, Hosgood G, Swindells KL, Mansfield CS. Diagnostic accuracy of the SNAP and spec canine pancreatic lipase tests for pancreatitis in dogs presenting with clinical signs of acute abdominal disease. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2014;24:135‐143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cridge H, MacLeod AG, Pachtinger GE, et al. Evaluation of SNAP cPL, spec cPL, VetScan cPL rapid test and precision PSL assays for the diagnosis of clinical pancreatitis in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32:658‐664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Watson P. Chronic pancreatitis in dogs. Topics in Compan an Med. 2012;27:133‐139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bennett PF, Hahn KA, Toal RL, Legendre AM. Ultrasonographic and cytopathological diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic carcinoma in the dog and cat. Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2001;37:466‐473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xenoulis PG. Diagnosis of pancreatitis in dogs and cats. J Small Anim Pract. 2015;56:13‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Newman SJ, Steiner JM, Woosley K, Williams DA, Barton L. Histologic assessment and grading of the exocrine pancreas in the dog. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2006;18:115‐118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Watson P. Pancreatitis in dogs and cats: definitions and pathophysiology. J Small Anim Pract. 2015;56:3‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Head KW, Cullen JM, Dubielzig RR, et al. Histological classification of tumours of the pancreas of domestic animals In: Head KW, Cullen JM, Dubielzig RR, et al., eds. World Health Organization International Histological Classification of Tumors of Domestic Animals: Histological Classification of Tumours of the Alimentary System. Washington DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2003:111‐118. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Watson PJ, Roulois AJA, Scase T, Johnston PEJ, Thompson H, Herrtage ME. Prevalence and breed distribution of chronic pancreatitis at post‐mortem examination in first‐opinion dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 2007;48:609‐618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cook AK, Breitschwerdt EB, Levine JF, et al. Risk factors associated with acute pancreatitis in dogs: 101 cases (1985–1990). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1993;203:673‐679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hess RS, Saunders HM, Van Winkle TJ, et al. Clinical, clinicopathologic, radiographic, and ultrasonographic abnormalities in dogs with fatal acute pancreatitis: 70 cases (1986–1995). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1998;213:665‐670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Watson PJ, Roulois A, Scase T, Holloway A, Herrtage ME. Characterization of chronic pancreatitis in English cocker spaniels. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25:797‐804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xenoulis PG, Suchodolski JS, Steiner JM. Chronic pancreatitis in dogs and cats. Compend Contin Educ Vet. 2008;30:166‐180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bostrom BM, Xenoulis PG, Newman SJ, Pool RR, Fosgate GT, Steiner JM. Chronic pancreatitis in dogs: a retrospective study of clinical, clinicopathological, and histopathological findings in 61 cases. Vet J. 2013;195:73‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Newman S, Steiner J, Woosley K, Barton L, Ruaux C, Williams D. Localization of pancreatic inflammation and necrosis in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2004;18:488‐493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Carney PC, Ruaux CG, Suchodolski JS, Steiner JM. Biological variability of C‐reactive protein and specific canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity in apparently healthy dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25:825‐830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang Y, Wang S, Zhou X, et al. Acinar cell carcinoma: a report of 19 cases with a brief review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:172 10.1186/s12957-016-0919-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pezzilli R, Melzi d'Eril G, Barassi A. Can serum pancreatic amylase and lipase levels be used as diagnostic markers to distinguish between patients with mucinous cystic lesions of the pancreas, chronic pancreatitis, and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma? Pancreas. 2016;45:1272‐1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kruger S, Haas M, Burger PJ, et al. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a rare disease with different diagnostic and therapeutic implications than ductal adenocarcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142:2585‐2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Steiner JM, Newman SJ, Xenoulis PG, et al. Histologic findings and minimally‐invasive serum markers in dogs with neoplasia involving the pancreas [abstract]. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21:650. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1 Signalment, clinical findings, cPLI values in dogs with histopathologically diagnosed normal or minimally changed pancreas (group 1, n = 40)

Supplementary Table 2 Signalment, clinical findings, cPLI values in dogs with histopathologically diagnosed mild pancreatitis (group 2, n = 8)

Supplementary Table 3 Signalment, clinical findings, cPLI values in dogs with histopathologically diagnosed acute and chronic moderate / severe pancreatitis (group 3, n = 12)

Supplementary Table 4 Signalment, clinical findings, cPLI values in dogs with neoplasm within the pancreas (group 4, n = 12)